Kidney transplantation after liver transplantation

2016-08-26LiYangWuHangLiuWeiLiuHanLiandXiaoDongZhangBeijingChina

Li-Yang Wu, Hang Liu, Wei Liu, Han Li and Xiao-Dong ZhangBeijing, China

Kidney transplantation after liver transplantation

Li-Yang Wu, Hang Liu, Wei Liu, Han Li and Xiao-Dong Zhang

Beijing, China

Kidney transplantation after liver transplantation (KALT) offers longer survival and a better quality of life to liver transplantation recipients who develop chronic renal failure. This article aimed to discuss the efficacy and safety of KALT compared with other treatments. The medical records of 5 patients who had undergone KALT were retrospectively studied, together with a literature review of studies. Three of them developed chronic renal failure after liver transplantation because of calcineurin inhibitor (CNI)-induced nephrotoxicity, while the others had lupus nephritis or non-CNI drug-induced nephrotoxicity. No mortality was observed in the 5 patients. Three KALT cases showed good prognoses,maintaining a normal serum creatinine level during entire follow-up period. Chronic rejection occurred in the other two patients, and a kidney graft was removed from one of them. Our data suggested that KALT is a good alternative to dialysis for liver transplantation recipients. The cases also indicate that KALT can be performed with good long-term survival.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2016;15:439-442)

liver transplantation;

kidney transplantation;

chronic renal failure;

calcineurin inhibitor(OLT) patients suffer from CRF.[2]Renal function in 90% of these patients can be restored,[2]but 2%-10% will develop end-stage renal disease (ESRD).[3]In addition,hemodialysis due to renal failure after LT also greatly increases the risk of progression to ESRD.[4]Therefore,kidney transplantation after liver transplantation (KALT)for patients with renal failure after LT is a good choice in terms of maintaining renal function and extending survival of the patient and graft. Currently, because of the high survival rates of both patients and grafts after the combined liver-kidney transplantation (CLKT), more CLKTs are performed on patients whose renal function may not recover after LT. This has led to few studies on KALT recently. Nevertheless, there is emerging data suggesting that some CLKT patients may regain native renal function, demonstrating poor utilization of renal grafts. Therefore, it is necessary to perform KALT on patients with irreversible renal failure after LT. This study aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of KALT based on the results of long-term follow-up of 5 patients as well as literature reviews.

Introduction

In recent years, chronic renal failure (CRF) has been acknowledged as one of the most important diseases seriously affecting the prognosis of patients with liver transplantation (LT).[1]According to reports and literature, 5%-50% of orthotopic liver transplantation

Methods

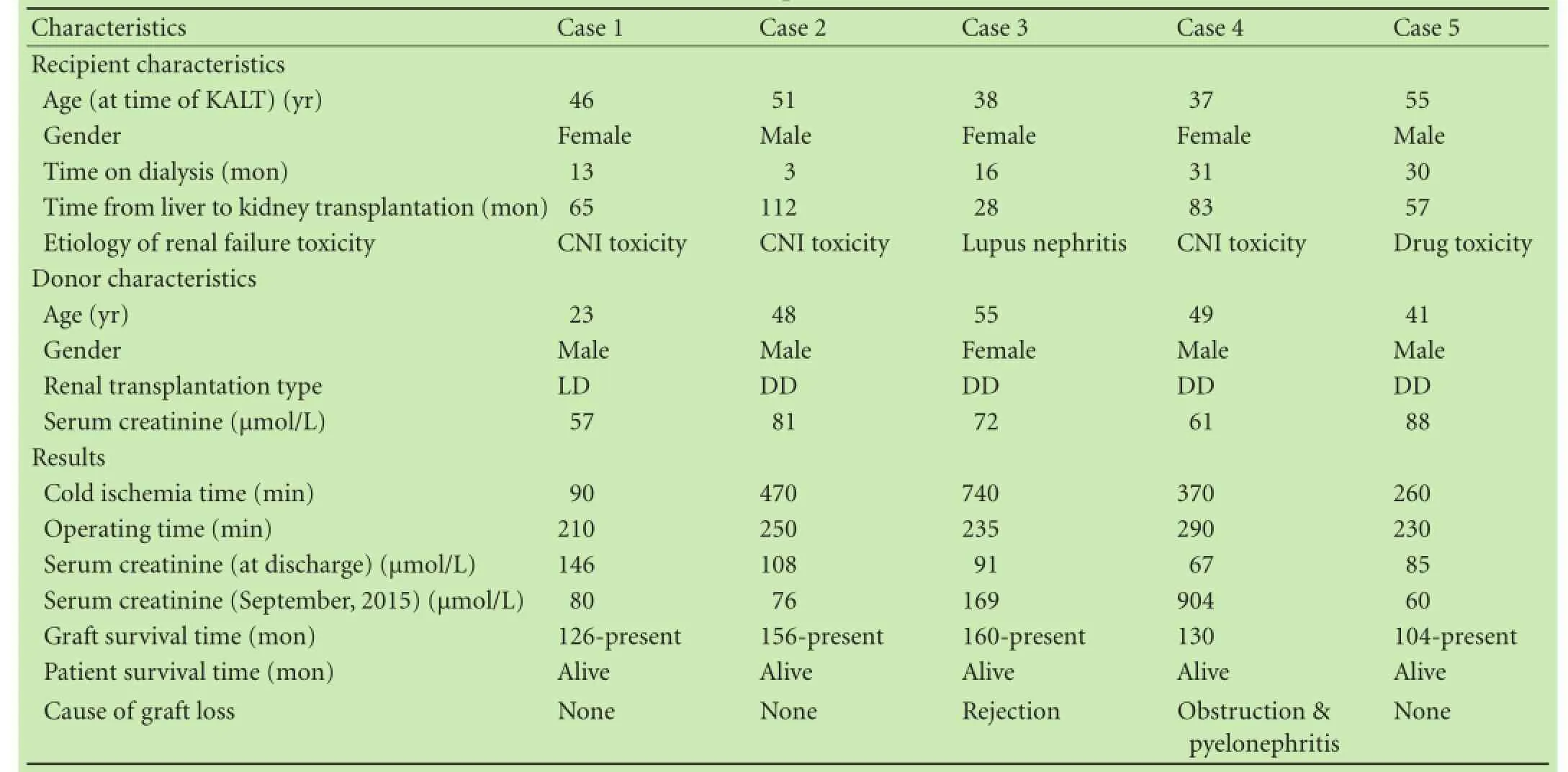

The records of 5 patients who had undergone KALT from 2002 to 2007 (the follow-up time were at least 8 years)were retrospectively studied, together with a literature review. Informed consent was obtained from these patients and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Chaoyang Hospital. There were 2 men and 3 women in this series, with a mean age of 45.4 years (range 37-55) when they received kidney transplantation. The mean follow-up time is 140.6 months (range 104-160)by the end of September of 2015. An overview of these patients is shown in the Table.

Results

All patients received LT because of hepatitis B-related liver cirrhosis, drug-induced liver failure, hepatitis C-related liver cirrhosis or liver cancer. One patient gothypertension and diabetes, one lymphatic tuberculosis and systemic lupus erythematosus, and another diabetes in past history. Cyclosporine (CsA), tacrolimus (FK506),mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) or combination of CsA and MMF was used as immunosuppressant. Calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs)-induced nephrotoxicity (n=3) was the main reason to receive KALT for patients, followed by lupus nephritis (n=1) and non-CNI drug-induced nephrotoxicity (n=1). There was no past history in all donors. The mean cold ischemia time was 386 minutes (range 90-740),and mean operating time was 243 minutes (range 210-290). The immunosuppressive regimen after operation was CsA+MMF+steroids (n=2) or FK506+MMF+steroids (n=3),and there was no acute rejection and surgical or infectious complication happened. One of them experienced a graft function delay lasting 15 days and recovered by hemodialysis. The level of creatinine of all patients was lower than 150 μmol/L (range 67-146) when patients were discharged. In September of 2015, the serum creatinine level in 3 patients was normal under the control of CNIs-based double- or triple-drug regimen.

One of these five patients had 23 years of lymphatic tuberculosis and 14 years of systemic lupus erythematosus. One month after KALT, the leukocyte count of the patient continued to decrease, which could not be reversed by reduction of the MMF dose. The symptom was under control after withdrawal of MMF. In 2008, the patient had micro-protein in urine; in 2013, MMF was added for proteinuria (++). Biopsy prompted chronic active antibody-mediated rejection in February of 2014 and creatinine was at 169 μmol/L in September of 2015. The patient is now taking FK506+MMF+steroids.

Another patient suffered from hydronephrosis in kidney graft and the serum creatinine increased to 436 μmol/L after discharged. Ureteral stent implantation was performed but renal dysfunction could not be reversed. Therefore, the patient received hemodialysis again. Six years later, the patient decreased the dose of FK506 herself (without the doctor's order) and then experienced hematuria and flank pain, which was relieved by adding FK506. The serum creatinine level was 766 μmol/L at that time. Three months later, the transplanted kidney was removed from this patient and her creatinine was 904 μmol/L in September of 2015.

Table. Characteristics of recipients and donors and results

Discussion

There is currently no definitive diagnostic criteria of the CRF after LT. Some scholars proposed a serum creatinine level ≥221 μmol/L continually after LT as diagnostic criteria of the CRF. However, serum creatinine is affected by many factors, including nutritional status, muscle mass,hepatic synthesis capacity as well as medication (such as methoxybenzyl aminopyrimidine) and therefore, serum creatinine is not able to accurately reflect the level of renal function. These factors have little influence on the glomerular filtration rate (GFR), so Sharma and othersused the GFR calculated by the modification of diet in renal disease formula to reflect renal function status post-LT: CRF is defined as an estimated GFR <30 mL/min persisting for ≥3 months or initiation of renal replacement therapy or being on the list for renal transplantation.[5]All of our 5 patients who met the diagnostic criteria for CRF received kidney transplantation.

A study[3]showed patients with higher preoperative creatinine are more likely to develop ESRD after LT. The majority of these patients suffer from hepatorenal syndrome. For patients with advanced liver diseases, hepatorenal syndrome is a common cause of acute kidney injury, which is also a reversible type of functional kidney damage.[6]However, there is still some irreversible kidney damage in patients with this disease.[3]

Diabetes mellitus is a risk factor of postoperative chronic kidney disease progression, and some scholars believe that the probability of developing severe renal failure after LT is 8 times greater in diabetic patients compared with that in normal population.[1, 7]On the one hand, patients who suffer from small vascular disease are more likely to develop renal failure. On the other hand, perioperative application of steroids increases the incidence of both diabetes and CRF.[8]Meanwhile, CsA and FK506 have been proven to damage the glucose tolerance and lead to hyperinsulinemia and further induce post-transplant diabetes mellitus,[9]which exacerbates the progression of CRF.

Hypertension puts liver transplant recipients at a high risk of CRF. Hypertension, both pre- and posttransplantation, induces the hyaline and fibrosis damage of glomerular arterioles which results in CRF. A summary of 294 cases of LT showed that the ratio of CRF in patients with hypertension was significantly higher than that of control group.[10]

Systemic infection caused by the HCV mainly involves the liver. Hepatitis C-related liver cirrhosis is the indication of LT in many countries. Meanwhile, chronic HCV infection may lead to various types of kidney disease. Furthermore, HCV cannot be removed by transplant, so it can lead to and aggravate kidney disease after LT.

Approximately 30% of the decreased GFR within the first 6 months after OLT was CNIs-related.[3]In addition,the incidence of severe renal dysfunction was 18.1% (CRF 8.6% and ESRD 9.5%) in OLT patients who were treated with CNIs and survived for 13 years.[3]A study, including 36 849 LT patients, 89% of whom treated with CsA or FK506 immunosuppression, found that the incidences of CRF after LT in 12, 36 and 60 months were 8%, 14% and 18%, respectively.[11]A recent study[12]showed that CNIs reduction or withdrawal improves the renal function of liver recipients. According to renal biopsies of recipients, CRF is mainly based on CNIs-induced nephrotoxicity,including hyaline deposits, tubular atrophy, interstitial fibrosis and glomerular sclerosis.

Congruent with previous literature, CNIs toxicity initiated renal failure in our center. However, the dosage of immunosuppressive agents after LT cannot be reduced, because an insufficient dose is likely to cause graft dysfunction. Gonwa[13]found that single MMF or sirolimus-withdrawal in double-drug regimen significantly increased the incidence of graft rejection which might be irreversible. Currently, there are still no specific immunosuppressive regimens for patients with KALT. According to previous reports, there are three existing alternatives for KALT patients: (1) if triple-drug regimen was used, continuing its use after KALT; (2) adding a new immunosuppressant if the patient was on a singleor double-drug regimen; or (3) converting the protocol after KALT.[14]

The pre-KALT immunosuppressive regimen was a single- or double-drug regimen, which was increased to triple-drug during the early period at our center. Better results were observed in three cases that received a triple-drug regimen persistently in the early stage. One suffered from chronic kidney rejection due to early antiproliferative drug withdrawal based on the decreasing leukocyte count; another reduced the dosage of FK506 herself, leading to hematuria and flank pain as well as eventual graft nephrectomy. Both of them, to some extent, confirmed Gonwa's finding.[13]

A 6-year follow-up study revealed that the survival rate of patients who received KALT was 71%, this rate was only 27% for those of LT only.[3]Paramesh et al[15]also reported that ESRD patients who received subsequent kidney transplantation had higher 10-year survival rates when compared with those maintained on dialysis after LT. The relative risk of death of KALT patients was similar to that of dialysis patients in 140 days after LT, and continued to decrease thereafter.[11]Levine and others[16]found that there was no difference in longterm survival between KALT and deceased donor kidney transplantation patients. The survival curves were almost the same in the two groups ten years after kidney transplantation. Compared to patients received deceased donor kidney transplantation, the incidence of postoperative complications significantly increased in KALT group,but the complications did not lead to graft loss. At the same time, there was no significant difference between two groups in terms of the incidence of renal rejection. Martin et al[17]elaborated the graft survival rate was also influenced by the time between LT and kidney transplantation. Six to twelve months after LT gave the highest graft survival rate in KALT patients.

The difference between KALT and CLKT has also been reported in the literature. Compared with CLKT patients, higher survival rates were observed in KALT patients within 1 year. This mainly depended on surgical complications.[18]However, the incidence of graft rejection in KALT was higher[18, 19]because the liver allograft provided renal graft immunoprotection if both organs are transplanted simultaneously and both organs are from the same donor and therefore, the gene is identical,while the liver and kidney are from different donors in KALT patients.[19]Rejection-free graft survival in KALT were also lower than those of CLKT patients. Nevertheless, Ruiz et al[20]believe that both KALT graft and patient survivals are similar to those of CLKT.

Overall, we consider KALT a good alternative to dialysis for LT recipients. Our cases also indicate that KALT can be performed with good long-term outcomes. The advantage of KALT compared with dialysis after LT and poor utilization of renal grafts in CLKT confirm the value of KALT. However, more cases of KALT are still needed to affirm these statements.

Contributors: ZXD proposed the study. WLY and ZXD wrote the first draft. Liu H and LW collected and organized the data. Li H corrected the manuscript. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts, and approved the final manuscript. ZXD is the guarantor.

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Chaoyang Hospital.

Competing interest: No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

References

1 Pawarode A, Fine DM, Thuluvath PJ. Independent risk factors and natural history of renal dysfunction in liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl 2003;9:741-747.

2 Fraley DS, Burr R, Bernardini J, Angus D, Kramer DJ, Johnson JP. Impact of acute renal failure on mortality in endstage liver disease with or without transplantation. Kidney Int 1998;54:518-524.

3 Gonwa TA, Mai ML, Melton LB, Hays SR, Goldstein RM, Levy MF, et al. End-stage renal disease (ESRD) after orthotopic liver transplantation (OLTX) using calcineurin-based immunotherapy: risk of development and treatment. Transplantation 2001;72:1934-1939.

4 Gonwa TA, Mai ML, Melton LB, Hays SR, Goldstein RM, Levy MF, et al. Renal replacement therapy and orthotopic liver transplantation: the role of continuous veno-venous hemodialysis. Transplantation 2001;71:1424-1428.

5 Sharma P, Welch K, Eikstadt R, Marrero JA, Fontana RJ, Lok AS. Renal outcomes after liver transplantation in the model for end-stage liver disease era. Liver Transpl 2009;15:1142-1148.

6 Hartleb M, Gutkowski K. Kidneys in chronic liver diseases. World J Gastroenterol 2012;18:3035-3049.

7 Lamattina JC, Foley DP, Mezrich JD, Fernandez LA, Vidyasagar V, D'Alessandro AM, et al. Chronic kidney disease stage progression in liver transplant recipients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011;6:1851-1857.

8 Baid S, Cosimi AB, Farrell ML, Schoenfeld DA, Feng S, Chung RT, et al. Posttransplant diabetes mellitus in liver transplant recipients: risk factors, temporal relationship with hepatitis C virus allograft hepatitis, and impact on mortality. Transplantation 2001;72:1066-1072.

9 Hjelmesaeth J, Hartmann A. Risk for posttransplant diabetes mellitus with current immunosuppressive medications. Am J Kidney Dis 2000;35:562.

10 Garces G, Contreras G, Carvalho D, Jaraba IM, Carvalho C, Tzakis A, et al. Chronic kidney disease after orthotopic liver transplantation in recipients receiving tacrolimus. Clin Nephrol 2011;75:150-157.

11 Ojo AO, Held PJ, Port FK, Wolfe RA, Leichtman AB, Young EW,et al. Chronic renal failure after transplantation of a nonrenal organ. N Engl J Med 2003;349:931-940.

12 Créput C, Blandin F, Deroure B, Roche B, Saliba F, Charpentier B, et al. Long-term effects of calcineurin inhibitor conversion to mycophenolate mofetil on renal function after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2007;13:1004-1010.

13 Gonwa TA. Treatment of renal dysfunction after orthotopic liver transplantation: options and outcomes. Liver Transpl 2003;9:778-779.

14 Ekser B, Furian L, Baldan N, Amico A, Fabris L, Lazzarin M, et al. Dual kidney transplantation after liver transplantation: a good option to rescue a patient from dialysis. Clin Transplant 2009;23:124-128.

15 Paramesh AS, Roayaie S, Doan Y, Schwartz ME, Emre S, Fishbein T, et al. Post-liver transplant acute renal failure: factors predicting development of end-stage renal disease. Clin Transplant 2004;18:94-99.

16 Levine MH, Parekh J, Feng S, Freise C. Kidney transplant performed after liver transplant: a single center experience. Clin Transplant 2011;25:915-920.

17 Martin EF, Huang J, Xiang Q, Klein JP, Bajaj J, Saeian K. Recipient survival and graft survival are not diminished by simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation: an analysis of the united network for organ sharing database. Liver Transpl 2012;18:914-929.

18 Fong TL, Bunnapradist S, Jordan SC, Selby RR, Cho YW. Analysis of the United Network for Organ Sharing database comparing renal allografts and patient survival in combined liver-kidney transplantation with the contralateral allografts in kidney alone or kidney-pancreas transplantation. Transplantation 2003;76:348-353.

19 Simpson N, Cho YW, Cicciarelli JC, Selby RR, Fong TL. Comparison of renal allograft outcomes in combined liver-kidney transplantation versus subsequent kidney transplantation in liver transplant recipients: analysis of UNOS Database. Transplantation 2006;82:1298-1303.

20 Ruiz R, Kunitake H, Wilkinson AH, Danovitch GM, Farmer DG, Ghobrial RM, et al. Long-term analysis of combined liver and kidney transplantation at a single center. Arch Surg 2006;141:735-742.

Accepted after revision February 26, 2016

Author Affiliations: Department of Urology (Wu LY, Liu H and Zhang XD), Department of Surgical Intensive Care Unit (Liu W), and Department of Blood Purification (Li H), Beijing Chaoyang Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing 100020, China

Xiao-Dong Zhang, MD, PhD, Department of Urology, Beijing Chaoyang Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing 100020, China (Tel/Fax: +86-10-85231383; Email: zhangxiaodong@bjcyh. com)

© 2016, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(16)60118-2

Published online July 13, 2016.

December 5, 2015

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International

- Dietary supplementation in patients with alcoholic liver disease: a review on current evidence

- Combined hepatectomy and radiofrequency ablation versus TACE in improving survival of patients with unresectable BCLC stage B HCC

- Effects of Salmonella infection on hepatic damage following acute liver injury in rats

- Long-term follow-up of children and adolescents with primary sclerosing cholangitis and autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis

- Letters to the Editor