Combined hepatectomy and radiofrequency ablation versus TACE in improving survival of patients with unresectable BCLC stage B HCC

2016-08-26YiFuHouYongGangWeiJiaYinYangTianFuWenMingQingXuLuNanYanandBoLiChengduChina

Yi-Fu Hou, Yong-Gang Wei, Jia-Yin Yang, Tian-Fu Wen, Ming-Qing Xu, Lu-Nan Yan and Bo LiChengdu, China

Combined hepatectomy and radiofrequency ablation versus TACE in improving survival of patients with unresectable BCLC stage B HCC

Yi-Fu Hou, Yong-Gang Wei, Jia-Yin Yang, Tian-Fu Wen, Ming-Qing Xu, Lu-Nan Yan and Bo Li

Chengdu, China

BACKGROUND: Combined hepatectomy and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) provides an additional treatment for patients with Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage B hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who are conventionally deemed unresectable. This study aimed to analyze the outcome of this combination therapy by comparing it with transarterial chemoembolization (TACE).

METHODS: We retrospectively reviewed 51 patients with unresectable BCLC stage B HCC who had received the combination therapy. We compared the survival of these patients with that of 102 patients in the TACE group (control). Prognostic factors associated with worse survival in the combination group were analyzed.

RESULTS: No differences in tumor status and liver function were observed between the TACE group and combination group. The median survival time for the combination group and TACE group was 38 (6-54) and 17 (3-48) months, respectively (P<0.001). The combination group required longer hospitalization than the TACE group [8 (5-14) days vs 4 (2-9) days,P<0.001]. More than two ablations decreased the survival rate in the combination group.

CONCLUSIONS: Combined hepatectomy and RFA yielded a better long-term outcome than TACE in patients with unresectable BCLC stage B HCC. Patients with a limited ablated size (≤2 cm), a limited number of ablations (≤2), and adequate surgical margin should be considered candidates for combination therapy.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2016;15:378-385)

hepatocellular carcinoma;

hepatectomy;

radiofrequency ablation;

transarterial chemoembolization;

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer system

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary hepatoma in the world.[1]In Asia,hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is the major risk factor of HCC.[2]According to recent data, there are 400 million people infected with HBV worldwide.[3]Liver resection and liver transplantation are the curative treatments for early-stage HCC.[4-6]However, the treatment for multifocal HCC is controversial. According to the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) system,liver resection is no longer suitable for multifocal HCC exceeding the Milan criteria (stage B), and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) is recommended.[3]However, tumor status in stage B HCC varies substantially, and researchers believe that some patients can still benefit from an aggressive surgical approach. Retrospective studies[7-9]have demonstrated that curative resection provides better survival than TACE and recently, a randomized clinical trial[10]showed consistent results that resection improves survival compared with TACE.

Nevertheless, a considerable number of patients with BCLC stage B HCC do not have the option of hepatectomy.[11, 12]For these patients, the non-curative therapeutic TACE is the only option. To increase curative chances for patients with multifocal HCC who on one hand can potentially benefit from surgery but on the other hand, resection is not feasible, the combination of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and partial hepatectomy (PH) was introduced.[13]These patients presented with a resectable dominant tumor along with some other HCC nodules. RFA is a common locoregional therapy, and ac-cording to previous studies, RFA can achieve complete necrosis of HCC lesions less than 2 cm in diameter.[3]The combination of PH and RFA may possibly eradicate all HCC lesions and preserve more hepatic tissue without injury to the major vessels.[14, 15]

This study was undertaken to compare the survival of patients treated with combined PH and RFA with that of those treated with conventional TACE in patients with unresectable BCLC stage B HCC. Furthermore, we analyzed the prognostic factors related to the survival of patients with HCC receiving the combination therapy and attempted to choose the suitable candidates for the treatment.

Methods

Patients

Patients who had been diagnosed with HCC in West China Hospital of Sichuan University from January 2008 to June 2012 were retrospectively reviewed. We enrolled HCC patients who had received the combination therapy. The inclusion criteria were: (1) adult male or female between the age of 18 and 70 years; (2) unresectable BCLC stage B HCC; (3) preoperative liver function corresponding to Child-Pugh A with normal total bilirubin (TB)levels; (4) no evidence of extrahepatic metastasis on preoperative 3-phase enhanced computed tomography (CT)or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); (5) pathological confirmation of HCC; (6) indocyanine green (ICG) retention rate at 15 minutes ≤15% for major liver resection(≥3 segmentectomy) and ≤20% for minor liver resection(<3 segmentectomy or non-anatomic resection); (7) a non-invasive diagnosis of HCC as per the American Association of the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) criteria[16]in patients with a diagnosis of liver cirrhosis: two rounds of radical imaging showed typical features of HCC (contrast uptake in the arterial phase followed by rapid washout in venous phase) confirming the clinical diagnosis of HCC. Percutaneous liver biopsy was not performed in our center. For some cases of small HCC with atypical imaging features, we followed the patients and reevaluated them three months later according to the guidelines; (8) at least 1 cm of margin was required for hepatectomy. Our exclusion criteria were as follows:(1) recurrent HCC; (2) residual tumor tissue found on the cutting edge; (3) performance status (PS) >0; and (4) other locoregional or systemic treatment carried out simultaneously with hepatectomy and RFA.

In the TACE group, liver function and tumor status were similar to those in the combination group. Preoperative TB, albumin (ALB), ALT, and AST levels were used to match the liver function of the patients. Tumor status was classified into four subgroups. Group Ia: tumor number ≤3, the dominant tumor >3 cm and ≤5 cm; group Ib:tumor number ≤3, the dominant tumor >5 cm; group IIa: tumor number >3, the dominant tumor ≤5 cm; and group IIb: tumor number >3, the dominant tumor >5 cm. Matching up was performed according to the subgroup of tumor status. For patients in the TACE group, at least 2 sessions of TACE were required. In this study, the definition of unresectable HCC in BCLC stage B was based on collective decision-making. Five liver surgery experts and one experienced radiologist determined the surgical options by evaluating liver function, ICG results, remnant liver volume on preoperative imaging scans, and other accompanying diseases.

We compared baseline demographic data and data on hospitalization, postoperative complications and survival outcomes between the two groups. The primary endpoint was the overall survival rate (OS); the secondary endpoint was the postoperative complication rate. The study was approved by our institutional review board.

Surgical combination therapy

For all patients, open surgery was performed by a single surgical team. Liver resection involved one dominant tumor within two liver segments or one lobe. A Cavitron Ultrasonic Surgical Aspirator (CUSA) was used to dissect the parenchyma under ultrasound guidance. According to tumor location, discontinuous selective hepatic occlusion was applied to control surgical blood loss. RFA was also performed under ultrasound guidance after hepatic resection. Before ablation, we scanned every inch of the remnant liver to locate and evaluate residual tumors. Every detected lesion was ablated using an internally cooled system manufactured by Valleylab (Boulder, CO, USA). A single-needle electrode with an exposed tip was inserted to the tumor bottom under ultrasound guidance. The process of ablation required at least 2 cycles, each lasting 5 to 10 minutes. Afterward, we rescanned the lesion to find out whether the ablative region had already covered the whole tumor. Therefore, a second or a third ablation would be carried out until a satisfying ablative area was covered. A final ultrasound examination was performed to confirm the absence of residual tumor tissue and complete necrosis after resection and ablation. No specimens were taken during the operation; suspicious nodules detected by ultrasound were all ablated, but only those larger than 1 cm in diameter were recorded as additional tumors. When HCC recurrence occurred, re-resection, RFA, TACE,or sorafenib was recommended to the patients according to the location of recurrence and health conditions.[17]

TACE

TACE was carried out under local anesthesia usingthe Seldinger technique, in which a 4F-5F French catheter was inserted to the abdominal aorta through the superficial femoral artery. Subsequently we performed hepatic arterial angiography, introducing the catheter tip into the superior mesenteric and celiac arteries under fluoroscopy guidance. After staining of tumors we identified the vascular anatomy around the tumors, selectively inserted the cathether tip into the tumor pathological arteries and infused with an emulsion of lipiodol of up to 30 mL, 5-fluorouracil 500-1000 mg, and adriamycin of up to 10 mg into the target arteries. Afterwards, a gelfoam fragment was injected to embolize the target arteries. After the procedure, the patients were requested to put pressure on the entry site for half an hour to ensure hemostasis. Imaging evaluation was performed one month after each session according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 (RECIST 1.1).[18]Each session was carried out with an interval of 1-2 months.

Hospitalization and follow-up

Total hospital and ICU stay was recorded by the hospital digital health care system. In assessment of postoperative complications, we used the Clavien-Dindo classification to characterize the severity.[19]All patients were followed up at our outpatient clinic once a month in the first year after surgery and once every 1-3 months afterwards. Blood routine tests, liver function tests, serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) tests, and abdominal ultrasonography were carried out at each follow-up. When a suspicious nodule was found on ultrasonography or persistent elevated AFP levels were observed, enhanced CT scan or MRI was performed for confirmation. Once HCC recurrence was diagnosed, radical treatment such as resection and RFA was our first choice for patients with sufficient hepatic reserve. TACE and sorafenib were palliative therapeutic options for HCC. For patients with uncontrollable HCC or a general performance status >2 or Child-Pugh C liver function, best supportive care was given. We followed the same strategy for treating recurrence after the second hepatectomy.

Statistical analysis

Baseline comparison between the two groups was analyzed using Student's t test for continuous variables,the Mann-Whitney U test for non-parametric variables,and the Chi-square test for categorical variables. Fisher' s exact test was applied to compare data on postoperative complications. Differences in cumulative OS rates between the two groups were analyzed by Kaplan-Meier survival curves and tested using the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard models were used to identify the prognostic risk factors affecting patient survival in the combination group. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed with SPSS version 21.0 (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Patient demographics

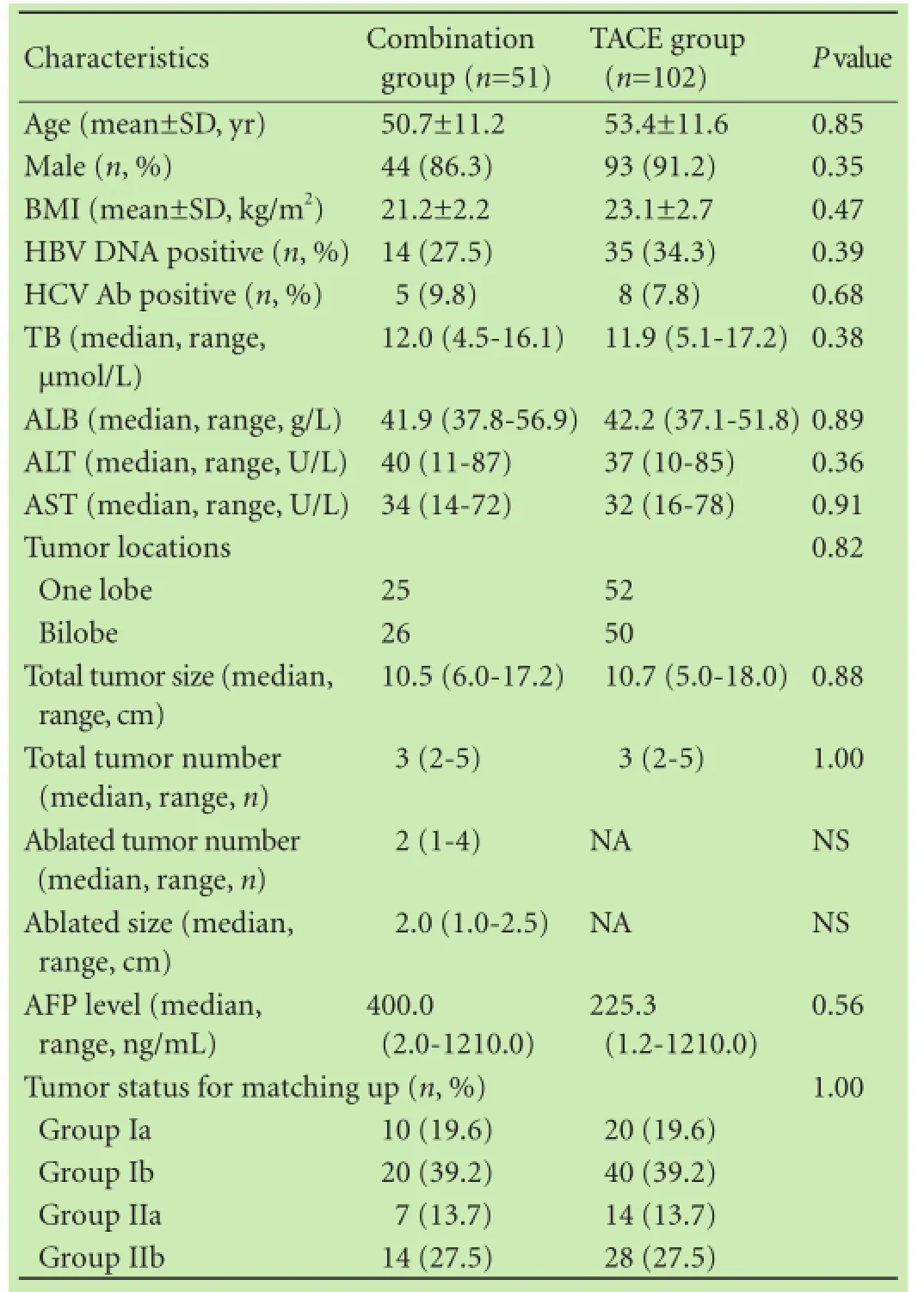

Strictly adhering to the inclusion and exclusion criteria,we included in this study 51 patients with BCLC stage B HCC who had received the combination therapy. In the TACE group, 102 HCC patients who had received TACE during the same period were included. According to the match-up results, 19.6% of the patients belonged to group Ia, 39.2% to group Ib and 13.7% to group IIa, and the remaining 27.5% belonged to group IIb in the combination therapy group and TACE group (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics between the combination group and TACE group

Patient demographics are summarized in Table 1. Incontrast to the TACE group, the combination group was characterized by a comparable age (50.7±11.2 vs 53.4 ± 11.6, P=0.85), male ratio (86.3% vs 91.2%, P=0.35), and body mass index (21.2±2.2 vs 23.1±2.7, P=0.47). The TB,ALB, ALT and AST of the TACE group was not different from that of the combination group (P=0.38, P=0.89,P=0.36 and P=0.91, respectively; Table 1). The HBV DNA positive ratios in the combination group and the TACE group were 27.5% (14/51) and 34.3% (35/102), respectively (P=0.39). Analysis of tumor status in the two groups showed that tumor size and tumor number in the combination group were similar to those in the TACE group (P=0.88 and P=1.00, respectively). With regard to tumor distribution, 51.0% (26/51) of the patients in the combination group and 49.0% (50/102) in the TACE group had bilobar HCC (P=0.82). In the combination group, the median ablation size was 2.0 (1.0-2.5) cm. The number of ablated HCC lesions in the combination group ranged from 1 to 4; 11 patients had one solitary ablated HCC lesion, 19 had 2 ablated HCC lesions, 12 had 3 ablated HCC lesions, and 9 had 4 ablated HCC lesions.

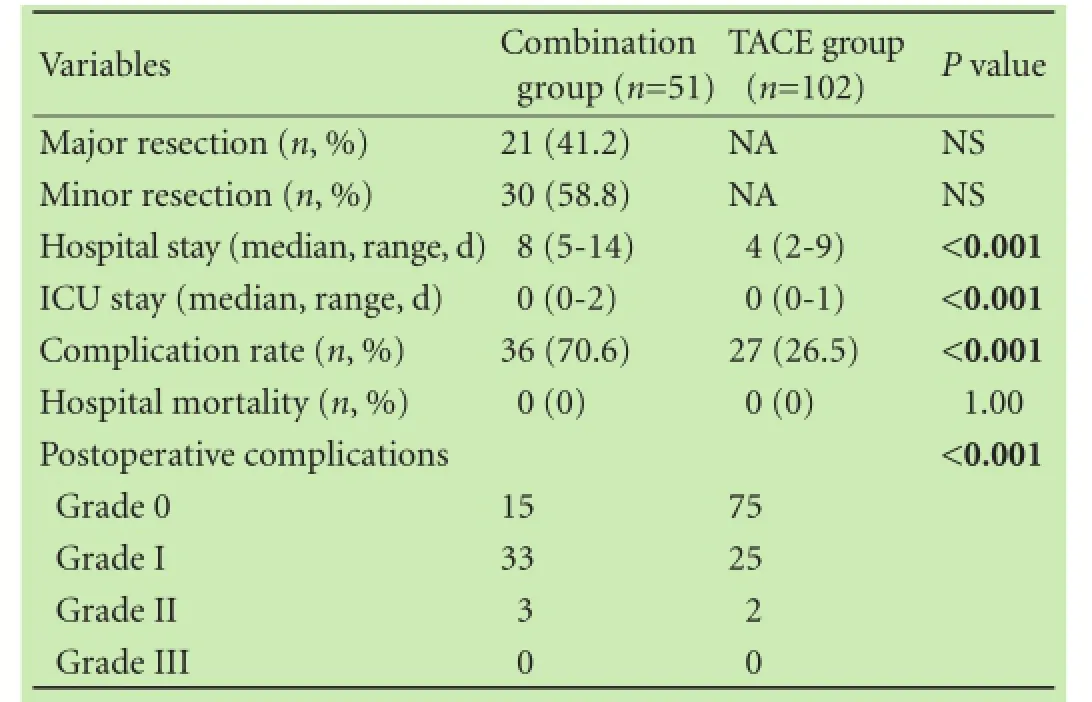

Postoperative outcomes

In the combination group, 21 (41.2%) of the patients received major liver resection and 30 (58.8%) received minor liver resection. The median hospital stay was 8 days (range 5-14) in the combination group and 4 days (range 2-9) in the TACE group (P<0.001). The median ICU stay in the combination group and the TACE group was 0 day (range 0-2) and 0 day (range 0-1), respectively (P<0.001; Table 2). There was no hospital-associated mortality in both groups. The combination group had a significant higher postoperative complication rate than did the TACE group (36 vs 27, P<0.001). According to the Clavien-Dindo classification, the combination group exhibited significantly severer results. Fifteen patients in the combination group and 75 in the TACE group showed no obvious complications. Thirty-three patients in the combination group and 25 in the TACE group had grade I complications. Three patients in the combination group and 2 in the TACE group had grade II complications (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of postoperative outcomes between the combination group and TACE group

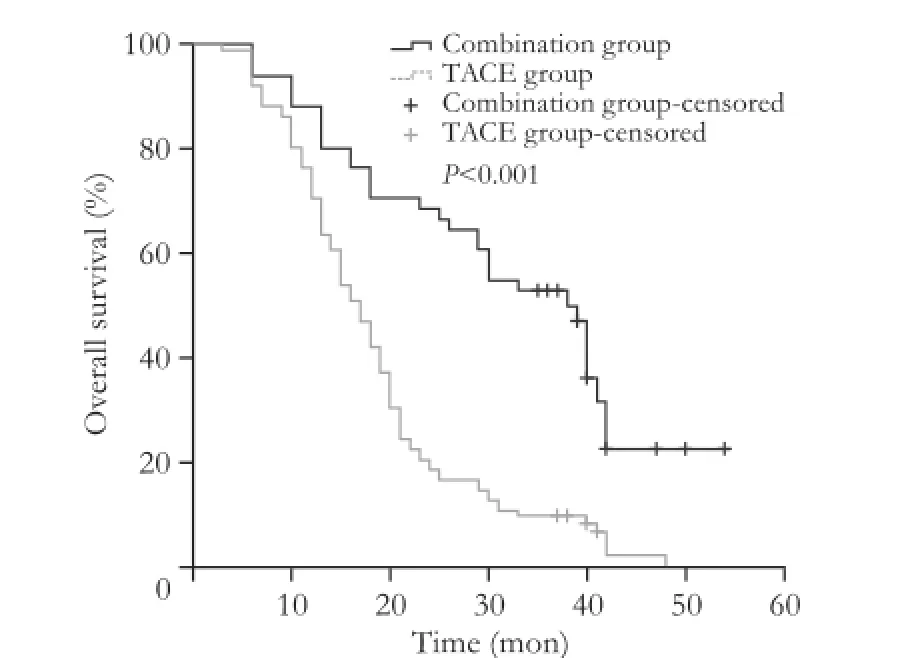

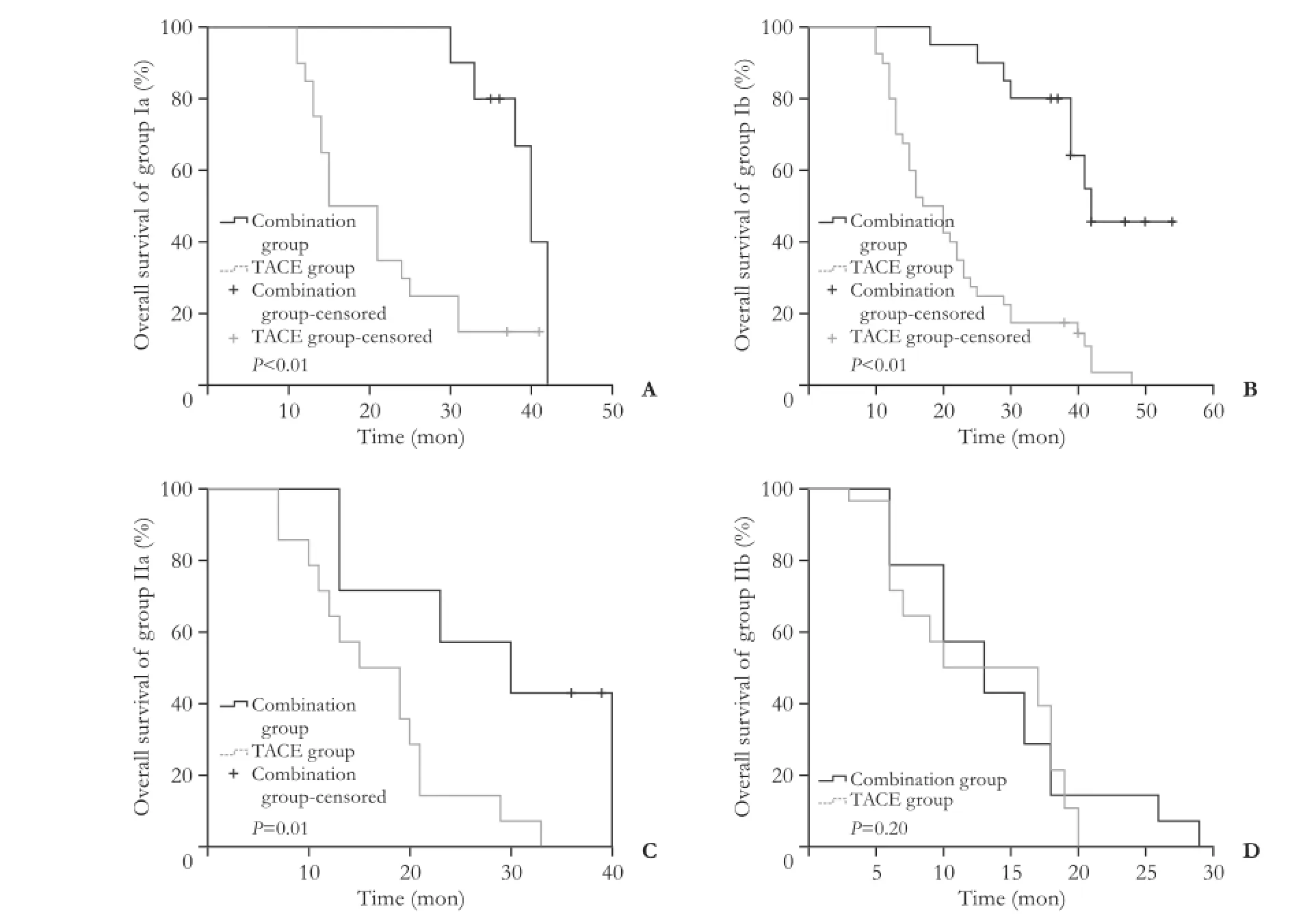

Fig. 1. Comparison of overall survival between the combination group and TACE group.

Survival outcomes

The median survival was 38 months (range 6-54) in the combination group and 17 months (range 3-48) in the TACE group (P<0.001; Fig. 1). The estimated 1-, 2-,and 3-year OS rates for the combination group and the TACE group were 88.2% vs 76.5% (P=0.84), 66.7% vs 20.6% (P<0.001), and 52.9% vs 9.8% (P<0.001), respectively. In the subgroup analysis, we re-compared the survival rates between the combination group and the TACE group stratified by tumor burden (Fig. 2). The results of the combination group were significantly better than those of the TACE group with regard to group Ia, group Ib, and group IIa; 40 (30-42) vs 15 (11-41) months, 42 (18-54) vs 17 (10-48) months, 30 (13-40) vs 15 (7-33)months (P<0.01, P<0.01, and P=0.01, respectively). In group IIb of the combination group, the outcome was comparable to that of the TACE group: 13 (6-29) vs 10 (3-20) months (P=0.20). In the combination group, the median disease-free survival time was 12 months (range 2-54). A total of 54.9% (28/51) of the patients experienced HCC recurrence within 1 year. The estimated 1-, 2-,and 3-year disease-free survival rates were 45.1%, 19.6%,and 11.8%, respectively. In the combination group, 21 (45.7%) of the patients had recurrence close to the surgical margin; 17 (37.0%) had tumors localized at the RFA sites, and the remaining 8 (17.4%) had tumors at bothsites. With regard to the time of recurrence, patterns were categorized into two types: type A, recurrence within 2 years and type B, recurrence after 2 years. In total,there were 46 patients with HCC recurrence, whereas 5 patients remained recurrence-free by the end of the study. About 10.9% (5/46) of the patients with intrahepatic recurrence belonged to type B. In the TACE group, after two sessions of treatment, no patients achieved complete response, 29.4% (30/102) of the patients had partial response, 36.3% (37/102) had stable disease, and 34.3% (35/102) had progressive disease. In the combination group, there were 32 deaths during follow-up, of which 96.9% (31/32) were cancer-related deaths. One patient died in six months after surgery following an accident. In the TACE group, there were 97 deaths during followup and all of them were cancer-related. No patients were lost to follow-up.

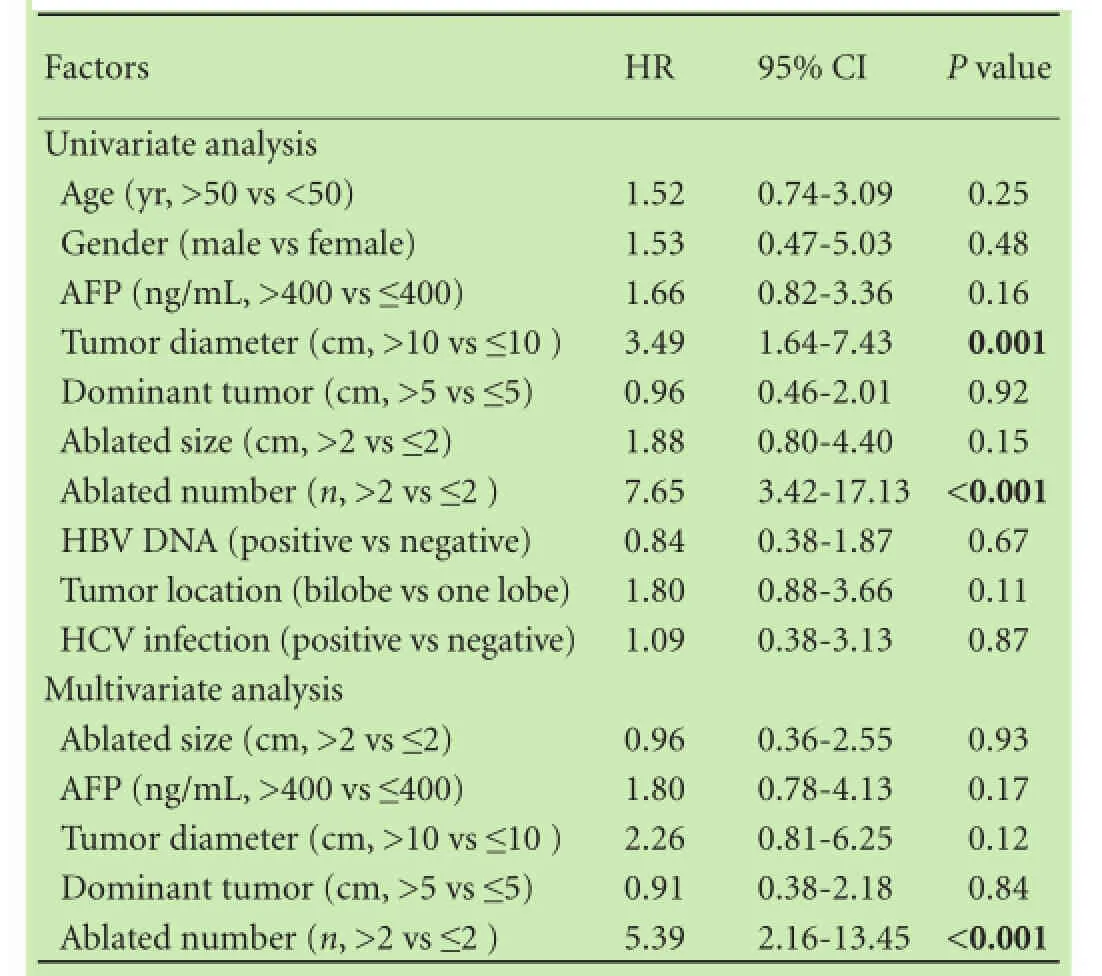

Univariate analysis revealed that factors significantly associated with low survival in the combination group included a total tumor diameter >10 cm [hazard ratio (HR)=3.49, P=0.001] and a number of ablated tumors >2 (HR=7.65, P<0.001). Factors with a P value <0.05 together with selected clinical significant variables, such as dominant tumor size, ablated tumor size, and AFP levels, were selected for multivariate analysis. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model showed that a number of ablated tumors >2 (HR=5.39, 95% confidence interval, 2.16-13.45, P<0.001) was a significant risk factor for survival (Table 3).

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate analyses of prognostic factors in the combination group

Fig. 2. Subgroup comparisons of overall survival between the combination group and TACE group.

Discussion

Despite the fact that the BCLC system recommends TACE for multifocal HCC beyond the Milan criteria, a series of retrospective studies have shown that liver resection provides a better survival outcome than conventional TACE.[7-9, 20]A randomized clinical trial showed a 3-year OS rate of 51.5% vs 18.1% for PH and TACE, respectively, in resectable multiple HCC beyond the Milan criteria.[10]The Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver recommended resection as the optimal treatment for resectable BCLC stage B HCC as long as there is adequate functional hepatic reserve.[21]However, there are still a great number of patients who are not candidates for hepatectomy. To increase the number of patients who could benefit from complete surgical intervention, RFA simultaneous with hepatectomy was introduced.[13, 22]This combination therapy was designed to eradicate all macroscopic lesions by resection of the dominant lesion and ablation of the residual nodules. For patients with BCLC stage B HCC who are deemed unresectable using hepatectomy only, the combination therapy provides them with an additional treatment option, augmenting the chances of curative treatment.

Our study showed for the first time that combined PH with RFA provided better survival than conventional TACE for patients with unresectable BCLC stage B HCC with Child-Pugh A liver function. A study[13]discussed the efficiency and safety of this combination strategy,showing intriguing the 3- and 5-year OS rates of 83% and 68%, respectively. In our study, the 1-year survival rates in the two groups were comparable. However, there was a sharp decrease in survival rate over the second year in the TACE group. The ultimate 3-year survival rate was almost four times higher in the combination group. This phenomenon showed that palliative intervention could not provide a satisfying long-term outcome in patients with a relatively large tumor burden. In China, HCC patients are usually younger and present with more severe tumor status because of maternal-neonatal transmission of HBV. This radical approach could provide these patients with a longer survival time. Moreover, in our subgroup analyses, we compared the survival results stratified by tumor burden and showed that the combination therapy had a significantly better outcome as compared with TACE, except in group IIb. This might imply that as the tumor burden gets more severe, radical treatment may fail to provide any additional improvement in survival. Therefore, not all cases of stage B HCC should be considered suitable for resection or combination therapy. Despite the longer OS, this combination therapy did not prevent a relatively high recurrence rate. Almost 50% of the patients had developed recurrent disease by the first year after surgery. The estimated disease-free survival rate of patients receiving the combination therapy was much lower than that of patients receiving hepatectomy for solitary tumors.[23, 24]The possibility of micro-intrahepatic metastasis missed by surgery cannot be ruled out and analysis of recurrence patterns supported our concerns. Type A was considered to include intrahepatic metastasis, representing early recurrence, and type B was considered to represent multi-centric occurrence, arising de novo in preneoplastic cirrhotic liver tissue. According to a study by Llovet et al, type B had better survival.[25]Only 10.9% of the patients belonged to type B and the majority of them were still at high risk of recurrence. However, we did not find any obvious pattern of recurrence sites in the combination group. Both surgical margin and RFA sites were considered void of residual tumor tissue by pathological examination and intraoperative ultrasound. Although we expected patients with multifocal HCC to have a poor prognosis, we still found the survival benefit entailed by surgical treatment.

Due to variability in tumor status in patients with BCLC stage B HCC, our original intention was to provide a chance of curative treatment for at least some of the patients. Therefore, suitable candidates should be carefully chosen for this combination therapy. The Cox proportional regression analysis indicated that a number of ablated tumors >2 was an independent risk factor related to OS. This result was consistent with early findings.[21, 26]Tumor number indicated the degree of intrahepatic spread, limited ablated number implied that the tumor has better biological behavior.[27, 28]As the number of ablated tumors increase, prognosis gets poorer because of intrahepatic metastases. Moreover, damage to the liver parenchyma caused by the ablation procedure became obvious. Besides the number of ablated tumors,the size of the ablated tumor should also be considered when matching the expected effect of RFA. Based on previous observations, RFA provides an outcome similar to that of resection in cases of HCC lesions less than 2 cm in diameter.[3, 13, 14]In our study, the largest nodule ablated was 2.5 cm, with 84.3% (43/51) of the lesions being smaller than 2 cm. Therefore, we still suggest an area corresponding to 2 cm to be the optimal upper size limit of the ablated area. Moreover, as described in the methods section, the dominant lesion should be void of vascular invasion and the ample surgical margin is critical. From our experience, we suggest that hepatectomy is restricted to one lobe with at least 1 cm of margin. This could both ensure preservation of sufficient hepatic reserve and at the same time lead to an optimal surgical result.

In terms of postoperative complication and hospitalization settings, patients underwent TACE treatment hadshorter hospitalization and fewer, milder complications than those treated with the combination therapy. No lifethreatening events occurred in any of the two groups, indicating that the combination therapy for patients with unresectable BCLC stage B HCC is safe.

Our study has some limitations. The retrospective nature and small sample size limit its validity. However as previously mentioned, BCLC stage B HCC patients differ substantially in tumor status. The combination therapy provided a proportion of patients with the option of surgical curative treatment. Further studies are required to confirm our results.

In conclusion, combined PH with RFA should be considered as a safe and practical option for patients with unresectable BCLC stage B HCC with Child-Pugh A liver function. However, not all of these patients would benefit from this combination therapy. Suitable candidates should have resectable dominant HCC restricted to one lobe, a number of ablations ≤2, and an ablated area measuring ≤2 cm (the West China Criteria). It is reasonable to suggest this combination therapy as a treatment option for a certain group of BCLC stage B HCC patients.

Contributors: HYF, WYG and LB designed the research, HYF analyzed the data, HYF and LB wrote the paper. WYG, YJY, WTF,XMQ, YLN and LB contributed to the operations. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts. LB is the guarantor.

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of West China Hospital.

Competing interest: No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

References

1 de Lope CR, Tremosini S, Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Management of HCC. J Hepatol 2012;56:S75-87.

2 Hussain SA, Ferry DR, El-Gazzaz G, Mirza DF, James ND, Mc-Master P, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Oncol 2001;12:161-172.

3 European Association for Study of Liver; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012;56:908-943.

4 Jarnagin WR. Management of small hepatocellular carcinoma:a review of transplantation, resection, and ablation. Ann Surg Oncol 2010;17:1226-1233.

5 Truty MJ, Vauthey JN. Surgical resection of high-risk hepatocellular carcinoma: patient selection, preoperative considerations,and operative technique. Ann Surg Oncol 2010;17:1219-1225.

6 Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 1996;334:693-699.

7 Nagashima J, Okuda K, Tanaka M, Sata M, Aoyagi S. Prognostic benefit in cytoreductive surgery for curatively unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma - comparison to transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. Int J Oncol 1999;15:1117-1123.

8 Inoue K, Nakamura T, Kinoshita T, Konishi M, Nakagohri T,Oda T, et al. Volume reduction surgery for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2004;130:362-366.

9 Hsu CY, Hsia CY, Huang YH, Su CW, Lin HC, Pai JT, et al. Comparison of surgical resection and transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the Milan criteria: a propensity score analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:842-849.

10 Yin L, Li H, Li AJ, Lau WY, Pan ZY, Lai EC, et al. Partial hepatectomy vs. transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for resectable multiple hepatocellular carcinoma beyond Milan Criteria: a RCT. J Hepatol 2014;61:82-88.

11 Ng KK, Vauthey JN, Pawlik TM, Lauwers GY, Regimbeau JM,Belghiti J, et al. Is hepatic resection for large or multinodular hepatocellular carcinoma justified? results from a multi-institutional database. Ann Surg Oncol 2005;12:364-373.

12 Llovet JM. Updated treatment approach to hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol 2005;40:225-235.

13 Choi D, Lim HK, Joh JW, Kim SJ, Kim MJ, Rhim H, et al. Combined hepatectomy and radiofrequency ablation for multifocal hepatocellular carcinomas: long-term follow-up results and prognostic factors. Ann Surg Oncol 2007;14:3510-3518.

14 Takayama T, Makuuchi M, Hasegawa K. Single HCC smaller than 2 cm: surgery or ablation?: surgeon's perspective. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2010;17:422-424.

15 Wang JH, Wang CC, Hung CH, Chen CL, Lu SN. Survival comparison between surgical resection and radiofrequency ablation for patients in BCLC very early/early stage hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012;56:412-418.

16 Bruix J, Sherman M; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology 2011;53:1020-1022.

17 Ishizawa T, Hasegawa K, Aoki T, Takahashi M, Inoue Y, Sano K, et al. Neither multiple tumors nor portal hypertension are surgical contraindications for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2008;134:1908-1916.

18 Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009;45:228-247.

19 Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004;240:205-213.

20 Lin CT, Hsu KF, Chen TW, Yu JC, Chan DC, Yu CY, et al. Comparing hepatic resection and transarterial chemoembolization for Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage B hepatocellular carcinoma: change for treatment of choice? World J Surg 2010;34:2155-2161.

21 Omata M, Lesmana LA, Tateishi R, Chen PJ, Lin SM, Yoshida H, et al. Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver consensus recommendations on hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Int 2010;4:439-474.

22 Pawlik TM, Izzo F, Cohen DS, Morris JS, Curley SA. Combined resection and radiofrequency ablation for advanced hepatic malignancies: results in 172 patients. Ann Surg Oncol 2003;10:1059-1069.

23 Chen MF, Hwang TL, Jeng LB, Jan YY, Wang CS, Chou FF. Hepatic resection in 120 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Arch Surg 1989;124:1025-1028.

24 Chen MF, Tsai HP, Jeng LB, Lee WC, Yeh CN, Yu MC, et al. Prognostic factors after resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in noncirrhotic livers: univariate and multivariate analysis. World J Surg 2003;27:443-447.

25 Llovet JM, Di Bisceglie AM, Bruix J, Kramer BS, Lencioni R,Zhu AX, et al. Design and endpoints of clinical trials in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:698-711.

26 Cucchetti A, Djulbegovic B, Tsalatsanis A, Vitale A, Hozo I, Piscaglia F, et al. When to perform hepatic resection for intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2015;61:905-914.

27 Zhao WC, Fan LF, Yang N, Zhang HB, Chen BD, Yang GS. Preoperative predictors of microvascular invasion in multinodular hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 2013;39:858-864.

28 Zhong JH, Xiang BD, Gong WF, Ke Y, Mo QG, Ma L, et al. Comparison of long-term survival of patients with BCLC stage B hepatocellular carcinoma after liver resection or transarterial chemoembolization. PLoS One 2013;8:e68193.

Accepted after revision December 22, 2015

Author Affiliations: Department of Hepatic Surgery, West China Hospital,Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, China (Hou YF, Wei YG, Yang JY,Wen TF, Xu MQ, Yan LN and Li B)

Bo Li, MD, PhD, Department of Hepatic Surgery,West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, China (Tel/ Fax: +86-28-85422867; Email: cdlibo@medmail.com.cn)

© 2016, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(16)60089-9

Published online April 20, 2016.

July 28, 2015

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International

- Dietary supplementation in patients with alcoholic liver disease: a review on current evidence

- Effects of Salmonella infection on hepatic damage following acute liver injury in rats

- Long-term follow-up of children and adolescents with primary sclerosing cholangitis and autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis

- Letters to the Editor

- Kidney transplantation after liver transplantation