建筑学的整体现象学方法

——以以色列“马阿甘·迈克尔集体农庄”居住区为例

2015-12-19妮莉波图加里以色列

妮莉·波图加里 (以色列)

陈瑾羲 闫少宁 [译] 杨 滔 [校]

建筑学的整体现象学方法

——以以色列“马阿甘·迈克尔集体农庄”居住区为例

妮莉·波图加里 (以色列)

陈瑾羲 闫少宁 [译] 杨 滔 [校]

本文的目的是展现我对实践中的整体现象学世界观的独特解释。我将证明这种方法以及所采用的、与传统截然不同的设计过程,是如何被应用到我设计并建造的一个居住小区中,实现在以色列所谓“集体农庄”的社会、经济和空间结构中。

整体性;现象学;设计方法;模式语言;邻里社区

妮莉·波图加里(以色列贝扎雷艺术与设计学院)

Nili Portugali, Bezalel Academy of Art and Design, Jerusalem, Israel

[译者] 陈瑾羲(清华大学) 闫少宁(北京林业大学)

[Translator] CHEN Jinxi, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China; YAN Shaoning, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China

[校对] 杨 滔(北京市建筑设计研究院有限公司)

[Proofreader] YANG Tao, Beijing Institute of Architectural Design Co. Ltd, Beijing, China

Received Date: September 19, 2015

基于我在以色列设计并建造的一个实际项目,本文试图阐释整体现象学的世界观在实践中的应用。近年来,这种世界观处于整个科学研究的前沿,涉及诸如宇宙学、神经生物学、心理学、量子物理、脑科学等学科,并与近期的复杂学理论相关。同时,这种世界观也与佛教观息息相关,它们都与我的工作紧密相关。

本文将阐述该方法和我所遵循的设计过程(一种完全不同于传统的设计过程)如何在设计的住宅区中得以运用,以及如何体现在“集体农庄”概念(形成于20世纪早期的以色列)的社会、经济和物质形态之中。在当今非常严谨的社会学框架下,介绍这种全新的概念模型成为可能,这是由于“集体农庄”在现实中发生了彻底的变化。这在21世纪已不可避免。

本文旨在针对有关普遍的公共性、挑战21世纪建筑等中心议题,激发广泛的公开讨论:我们应该如何改造现有城市或自然环境?当我们在环境中建造全新的当代建筑时以及尽可能地发挥当代科技时代的潜能时,哪些方面我们必须尊重和保护。

图1 / Figure 1

图2 / Figure 2

图3 / Figure 3

本文对一些诸如“品质”或“采纳保护环境的价值观”等术语的定义,比通常的含义更为广泛。这将在下文中进行讨论。

1 自传大事年表以及整体方法论的发展背景

我是一名在以色列从事建筑实践超过40年的建筑师,不仅关注创作实践,而且重视理论研究,并与整体现象学派的理念紧密联系。

本节将阐述我从业过程中建筑学领域涌现的思潮,包括整体方法论的出现。这些思潮与我 “成长旅程”(journey)中的大事件有所联系,对我的各类创意作品产生了重要影响,尤其是建筑设计作品。

这些认识源于多方面知识,包括正式的建筑学学习、教学及研究工作,对佛学的研究以及我成长的小镇,即神秘的犹太之城萨法德(Safed)①。最后一项最为重要,因为我的家族自19世纪居住在这里已经有7代,这里是我的血统和根(图1、图2)。

20世纪60年代末,作为海法(Haifa)以色列理工学院(Technion Institute of Technology, Israel)建筑学一年级的学生,我开始对有机建筑的本质产生兴趣。

当时,我想了解:是什么隐藏在那些场所和建筑背后,而让我们有了“家”的感觉;是什么让它们变得如此美丽而富有灵性,促使我们一次一次回味无穷。只有了解这些建筑的创作过程,才会理解上述一切。

我的直觉是隐藏于这些场所和建筑背后的是事实、原因以及客观真相。我想了解这一切,并在设计作品中进行演绎。

20世纪60年代中期是建筑学界的一个转折点。当时的感觉和共识是,机械的世界观已经破产,因为基于此世界观的现代主义建筑并未就人与环境的关系给出合适的答案。例如,巴西的巴西利亚、印度的昌迪加尔、20世纪60年代末和70年代的英国米尔顿·凯恩斯(Milton Keynes)等卫星城以及1967年战后建成的以色列新住区,都是采用机械的方法论进行设计和建造。该方法论的建构者之一是著名的建筑师勒·柯布西耶(Le Corbusier)。显然,他对遵从此方法论而造成的灾难性后果负有责任。这些异化的场所明显表现出缺乏有机的秩序。然而,现代建筑固有的内在影响力,就如同当代建筑所固有的一样,均已获得了强大的簇拥,以至于大多数人曾经、并仍然畏惧表达自己的保留意见,更不会对此进行改变。

20世纪60年代末和70年代初,定量方法论成为科学界普遍的前沿,也成为了建筑学界关注的焦点,正如布罗德本特(Geoffrey Broadbent)的著作《建筑设计,建筑和人文科学》(Design in Architecture, Architecture and the Human Sciences, John Wiley & Sons 1973)所论述的那样。依据这一理论,创作过程是定量规划方法的产物,人与其所处的环境之间的复杂关系可由矩阵和公式来定义。我采用这种逻辑性和系统性的工作方式,界定和分离建筑项目中所需的不同元素,然后再组合成一个整体。这使得设计成果在传统意义上是完整的、合理的和一致的。采用这种机械方法论设计的项目,虽然满足了使用者的物质和社会需求,但仅仅部分地解决了其情感和精神需求。换言之,这种方法不以创造具有灵魂的建筑为目的。

对现代主义的失望引发了对新方法的探寻。20世纪70年代初,我离开以色列理工学院,前往伦敦A.A建筑学院继续求学。这所学校的建筑教学主题关注概念,这与当时概念艺术蓬勃发展的前景是一致的。伦敦当代艺术中心举办的“当态度成为形式”(When Attitude Becomes Form)的展览中首次提出概念艺术,这成为艺术领域的里程碑(图3)。当时,在A.A建筑学院举办的各次讨论中,人的环境被仅仅看成是科幻小说的隐喻。那些试图去解释人与场所之间 “情感与人”体验关系的先锋者被完全忽视,甚至受到贬低。

这种概念性方法的发展引发了一系列思潮的出现,每一种都试图以自己的方式,寻找途经走出现代建筑带来的失望或绝望。在这些思潮中,伦敦的“建筑电讯派”(Archigram)(根据该理论,15年后其他人在巴黎建造了蓬皮杜艺术中心)、美国东海岸的“纽约五人组”为代表的“后现代主义”流派、坚持历史的“新传统”学派以及至今仍然活跃的“解构主义”思潮。这些思潮虽然彼此不同,但有一个共同的基本观点:建筑的背后没有绝对真实,美和舒适是主观感受,与风格、潮流以及创造者的个人视角都相关。事实上,这种观念否定了对“美的建筑”的任何客观而公共的讨论。这些思潮都没有试图去严肃地直面眼前危机,或为解决危机而做出改变。

1973年完成学业后,我接到的第一个项目是为作家大卫·舒茨(David Schutz)在耶路撒冷设计住宅。设计地块被石头房屋所环绕,场地中央有棵柠檬树。

传统的设计过程是在办公室纸上谈兵,然后将设计应用到场地中。但是,我试图切身感受和体验场地中发生的一切,此次设计的所有决策都是在现场进行的。我的第一个设计决定就是在原处保留柠檬树,住宅围绕着它建造。我多次前后走动,寻找“感觉正确”的住宅边界,即住宅墙体的位置(图4、图5)。在这种情况下,房屋明确地从场地中生长出来,但仍然有一些重要的问题尚未解决:怎样的法则或设计过程能够确定房屋各部分之间的正确关系,从而使其成为一个整体?怎样的“粘合剂”使得建筑具有统一感?换言之,建筑和谐的秘密是什么?

我尝试去记录并理解那些曾接触过的场所,其中具有永恒而有机的可见结构(图6),然后将它们作为设计新项目的参照。但是,结果并不令人满意。这使得我意识到:没有场所是自我存在的,即没有场所是独立于其所在的特定现实而存在的;当新设计的场地需要获得那种场所品质时,需要的不仅是参照一个现有的场所模型,而是深刻理解创作那样场所的遗传密码(Genetic codes)及其设计过程。

20世纪70年代和80年代初,我在美国加州大学伯克利分校的“环境结构研究中心”与克里斯托弗·亚历山大(Christopher Alexander)一起工作。该研究机构由亚历山大在20世纪60年代中期创立,并发展至今。我对他的所有研究成果非常熟悉,并参与了以色列Shorashim互助村庄的规划。这次理论和实践的双方面经历,让我对建筑秩序的本质和创作过程有了深刻而可行的认识。

亚历山大在20世纪60年代中期所提出的观点,与之前提到的那些思潮截然不同。这是一种因其独特定义而得到大量设计反馈的方法论。其基本观点是秩序和美是客观属性,存在于事物的结构内部之中,感受必须与事实相关且基于那些控制场所品质和美的绝对准则(第5节将会详细论述)。

此后,我接触到佛学理论的逻辑,了解了整体方法论的基础,并尝试在设计作品中将其付诸实施。

整体方法论(第3节将会详细阐述)是一种广泛而普遍的方法论,与机械世界观相冲突,后者在西方世界的传统中更为常见。

然而,当我沿着自己的独特道路探究时,获得启发并意识到,在这个人生旅途中,我自己就是各种问题的答案,这就在我的童年中,在祖母65年前建造的小旅馆中(图7),在萨法德老城一条小巷尽头的小石头房子中,也在整个小巷中。

这样的经历极大地影响着我“感受”某个场所的方式以及定义“设计艺术”的洞察力。这些场所的形成,来自于我观察祖母在小旅馆的厨房里做饭,或来自于我用浅蓝色涂料粉刷小巷的墙壁(图8、图9)。

我一直以为我对萨法德强烈的情感依赖源于主观经历,但随后我意识到,那些来自不同于我们的地域、文化和传统的人也具有类似的体验。这让我明白一些更为本质的东西在那里发生。正如后文中阐述的那样,这对我们全人类是普适的。

2 建筑是为人设计的——建筑的现象学方法

依我所见,建筑学首要的和最重要的目的在于为人类营造人居环境。然而,现代社会已经丧失了其核心价值——人,因此创造出来的环境导致人与场所的疏离感。

建筑影响着我们多年生活的物质环境的命运以及我们本身的长期生活。因此,建筑的真正考验是来自时间的考验。美好的建筑让人有“家”的感觉,我们总想回到那里,无论过去还是现在;它们拥有超越时间的品质,触动我们的心灵并有能力释放我们的感觉。

尽管这种永恒特质存在于不同地域的建筑中,根植于不同的文化和传统中,但无论人们来自哪里或源于哪种文化,它们给人的体验是类似和相通的(图10~12)。

描述具有这种永恒特质的建筑有很多种方式。赖特(Frank Lloyd Wright)称他们“言辞不足以表达”。引用斯蒂芬·格拉伯(Stephen Grabow)的一句话:“有精神价值的建筑是内在世界的图示或是内在灵魂的影像。”

这种体验是人与社区邻里之间的情感联系,存在于人与环境之间各个层面的关系之中。在城市尺度上,这表现在建筑对公共空间体验之中。在室内空间,这表现在灯具、家具、门把手等使用者与场所之间最亲密层级的细节体验中。当代建筑及概念艺术试图将自身从情感世界中抽离开来,将设计过程只与概念和图像所构成的世界相联系,因而形成了一种人与建筑之间合理的但却缺乏情感的关系。本文在此阐述的基本观点是,如果试图改善环境的观感,创造使人具有归属感并希望生活在其中的建筑和场所,当务之急并非改变建筑的风格、潮流或设计者的个人视角,而是应采用一种全新的世界观。现有思想和方法背后的那些世界观正在威胁我们生存的物质和人文环境。整体现象学思想将会使其做出改变。

3 两种世界观(整体方法论与机械方法论)之间——局部与整体的关系

这两种不同的世界观的区别是,一种是将人从环境中分离开来,而另一种世界观认为人是其生存的物质世界和自然的一部分。这彰显了整体有机的思想体系与机械碎片化世界观的差异。我的设计属于前者。这是两种不同的秩序体系。

图4 / Figure 4

图5 / Figure 5

图6 / Figure 6

图7 / Figure 7

图8 / Figure 8

在西方传统中,机械世界观一直占据主导,并且构成当代建筑学的基础。这使得建筑组成元素彼此分离,各个自主的碎片构成了机械呆板的环境,正如我们所看到的诸如巴西的巴西利亚、印度的昌迪加尔、英格兰的卫星城那样的空间。或者,这也存在于1967年后耶路撒冷建成的新社区,那里的房屋与街道、街道与社区、社区与城市之间存在结构性的脱节,令人产生冷漠感和疏离感。

建筑看起来像是一堆物品的随机组合;街道像是一组房屋或房屋类型的随机组合,甚至还只是工厂预制并运输来的单元被强加在场地上,并未真正形成街道(图13);街道没有形成社区;社区也没有形成城市。

与这些建筑相反的案例是在传统村落和城镇中那些由不知名建筑师或非专业人群设计的建筑。设计者显然考虑了我们自身,即那些常常在公共空间中漫步的行人。他们懂得所设计建筑担负的责任,其中首要且最重要的就是街道的品质及其边界。他们知道,城市设计不是在一张1:1000的草图上武断地勾画线条,而是要时刻设想1:1的比例,即人的尺度。这是一种沉浸于其中的体验,正如眺及阳台上的栏杆或窗户上的铁栅栏,或在房子的入口庭院中观看果树、嗅闻气味(图14)。

这种方法论并不被柯布西耶、奥斯卡·尼迈耶(Oscar Niemeyer)和世界上其他现代主义者所理解,因为他们是机械论思想体系的一部分。还有部分当代建筑师同样不理解这种方法论,他们有意识地认为,建筑不过是标志物、环境装置或烟花表演。上述这些人对我们所生活的物质环境中比比皆是的灾难负有直接责任。

多年来,整体有机方法论已处于普遍科学思潮的前沿。社会物质环境被视为一个系统或一个动态整体,其存在依赖于各部分之间恰当且不断变化的内在联系(图15)。同时,各部分的产生和存在也取决于该部分和系统之间的互动联系。

佛教描述了相同的理论:任何存在的实体皆依赖于其他的因素和环境。这是对“缘起”的理解,即原因和条件是实现“空”(emptiness)的必要条件。这也是佛教哲学的基础。在几代人科学研究的基础上,这种“微妙无常”获得了科学的证实。

在任何一个有机系统中,当每个元素具备独特性并发挥作用时,它们总是作为其所从属的更大实体中的一部分发挥作用的。基于此,我认为城市设计、建筑设计、室内设计和景观设计不是孤立的、彼此不相联系的学科,而是一个连续而动态的系统过程。任何尺度上的任何设计细节,都源自其所从属的更大整体,都试图完善其整体并对其表征负责。无论在一栋建筑、一条街道、一个社区或一座城市中,这种内在的整体性和统一性都构成了总体感觉,最终都源于其各部分之间恰当的内在联系。

这一观点指引着我进行设计实践。我在设计“集体农庄”之初,首先考虑的就是开放空间系统,而非房屋本身。所有关于房屋选址、体量、高度和建材的决定,都源自公共景观的场所精神,也就是它所从属的更大系统,它必须对此整合、尊重和强化。

4 “集体农庄”生活中结构性改变需要全新的建造理念——从量的统一到质的平等

众所周知,“集体农庄”的社会、经济和形态结构形成于20世纪20年代初的以色列(图16)。从一开始,其终极价值观就是平等。然而,转译到社区生活领域中,则并非本质意义上的机会平等,而是形式的统一。这种教条式的平等抹杀了自我认知和作为个体的独特性,只将个人视作集体的一部分。

不过,近年来这种陈旧的平等观念已在许多方面被重新定义。社会结构回归到核心家庭理念,即孩子在家庭中被抚养,而不再是在公有房子中养育,孩子也不再被视为整个社区的共同所有物。以前工资虽基于每个成员的能力,但还是按照需求进行分配;而现在分配标准也发生了变化,工资取决于成员的个人贡献。

对于陈旧而简单的平等观念,“集体农庄”的住房也许是最后的堡垒。在今天,这种观念必须作出改变。根据平等观念,房屋被要求形状统一,作为静态模型被武断地放在建筑场地上。光线方向、面向特定方向景观的视野角度等环境因素都被弃之不顾。其结果是所有的房子都是同样的平面和立面。因此,住户房子的窗户碰巧对着果园的,就比那些面向奶牛棚的要强。

这种做法导致房子品质的不平等,也造成了住户之间机会的不平等。不仅如此,这种教条式做法的结果是,内盖夫(Negev)沙漠环境中的房子与加利利(Galilean)丘陵中的房子是完全一样的。

我设计的“马阿甘·迈克尔集体农庄”住宅采用了完全不同的新模型。这一模型根据过去20年中以色列“集体农庄”的实际变化做出了相应的调整。

图9 / Figure 9

图10 / Figure 10

图11 / Figure 11

图12 / Figure 12

图13 / Figure 13

图14 / Figure 14

5 规划过程

这种社区设计的方法就是房屋必须从其所建造的场地上自然生长出来,而不是强加在场地之上。

对场地做出规划决策之前,需要对“集体农庄”社区需求进行定性和定量的研究。此后,这些需求被转译成常规的“模式”列表。尽管这些“模式”很抽象,但它们具体界定了房屋的空间秩序。

从常规模式与实际场地的居住现实之间的深度互动中,可逐步提出场地设计和房屋布局方式;不同场地的实际情况各不相同。

5.1 住区的生成语言——一种模式语言

亚历山大在《建筑的永恒之道》中指出,有机秩序的场所可能看似未经规划且无序,而实际上清晰地表达了深刻而复杂的秩序。这种秩序基于严格的法则,而这些法则一直决定着场所的品质和美,并是其美好感受的源泉。换言之,某个场所中发生的事件模式与构成该场所的物质形态模式(术语是空间模式)之间存在着直接联系。

此外,以色列萨法德的庭院里那些触动我们的感受同样可以在中国北京的胡同中体会到。当我们在以色列萨法德的小巷中漫步时,那些打动我们的品质同样也能在意大利的锡耶纳或是中国的丽江感受到(图17、图18)。

20世纪60年代中期,“环境结构研究中心”开展了一项超过10年的经验研究,旨在对那些拥有共通事件模式和相似感觉的场所进行分析,以进一步归纳共同的元素。

其基本假设是,如同物质由原子这种基本单元构成,人造环境由被称为模式的众多原子构成。每个模式都是一种结构原型,并以各种方式不断重复。虽然它的形式在不同地方表现不一,但其潜在结构(即原型)是一样的。

当我们遇到一棵从未见过的非洲树木时,仍然可以辨认出这是一棵树。这是由于我们能识别的“树”并非指其形式表象,而是其潜在结构,即树各个部分之间的关系。虽然形式的重复表征有无穷的多样性,但是其关系的模式保持不变(图19)。

《模式语言》中列出了250条模式。这些模式的重要性在于它们组成了一个系统,并形成了一套完整的语言体系。书中模式涵盖内容涉及城市、建筑单体,乃至构造细节等多层尺度。该语言的每种模式由其他更小的模式构成,且同时是更大模式的一部分。换句话说,每种模式都是关系的模式。语言由此衍生发展,其模式的等级秩序由语言本身的法则所决定。和在语言使用中赋予句子意义的法则类似,最终创造有意义的一座城市、一条街道或一幢房屋的法则被称为句法。

环境由模式组成,它们能让来自各种文化或地域的人群均能产生共通的舒适感,那么这些模式显然跨越了文化边界。因此,亚历山大认为,在物质空间中存在着模式,它们反映了架构在我们脑海中与生俱来的模式。这与语言学家乔姆斯基(Noam Chomsky)的概念一致,在各种口语中被定义为语言的语言。

“集体农庄”规划过程的第一步是确定与该项目相关的空间模式。这些模式源于两方面因素:一是“集体农庄”的社会架构及其面向地中海的地理位置;二是我们作为人类的普遍基本需求。例如,无论在老年中心还是幼儿园,无论在印度还是在以色列,自然采光对人们的身心健康都是不可或缺的。根据不同的场地条件,这些普遍的模式抽象而又具体地定义了房屋的空间秩序,于是各式各样的房屋随即产生,且共用一种建筑语言(图20、图21)。

例如:

——住区入口大门:住区设计前期的决策之一是进入场地的入口大门选址。大门的位置决定了新住区与已有“集体农庄”能否融为一体。

——朝南的户外空间:将建筑放置在与之配套的户外活动空间的北侧。保持户外空间朝南向阳。永远不要在房屋和户外有阳光照射的空间之间留下大片的阴影。如果出现面向海的方向与向阳朝向发生冲突的情况,建筑位置需根据具体情况权衡确定(图22)。

——建筑各部分采光 :将建筑分解成多个部分,以适应房屋中的各种生活活动。合理设计每一部分,使得所有房间都可以有自然采光。

——建筑入口过渡空间:在路径或街道与入户门之间设置过渡空间。通过改变方向或变化铺装等视觉改变方式将其突出(图23)。

——建筑主入口:在基地中确定道路和建筑所在区域之后,下一步工作,或许是方案深化中最重要的步骤,就是为建筑主入口大门选择合适的位置。将建筑的主入口放置在一个节点位置,使之在进入建筑的主要街道上就清晰可见。同时,入口被设计成大胆而易辨识的形状,从建筑立面上凸显出来(图24)。

——专注的禅宗观:如果室外的风景特别美丽,建造一扇巨大的落地窗会对其造成破坏,这种做法只会让风景变成一张普通的壁纸。独特的风景应采用景框的方式予以突出(图25)。

图15 / Figure 15

图16 / Figure 16

图17 / Figure 17

图18 / Figure 18

图19 / Figure 19

经验告诉我,安装窗户时,哪怕出现10cm的偏差,也会破坏它本来设计应获得的所有效果。因此,窗户的精确位置只有在场地上才能确定。

5.2 在场地中规划社区

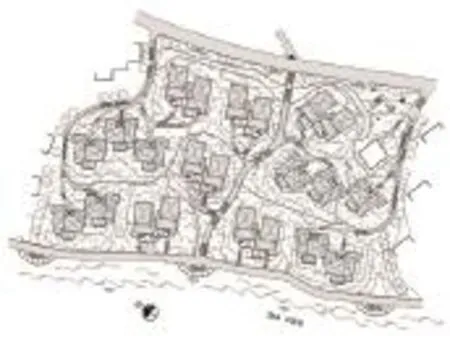

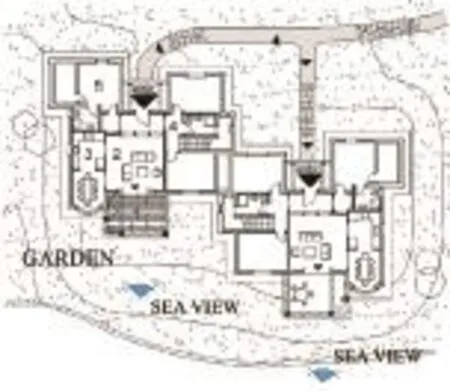

“马阿甘·迈克尔集体农庄”坐落在一座山上,新社区位于其西侧,面向大海(图26)。

这里提出的规划过程,与常规过程有着本质区别。在常规规划过程中,规划方案是事先在办公室中生成的,场地总平面和房屋形式也都是事先确定的,与场地的实际状况毫无关联。但是在我的设计中,规划图纸只不过是场地中规划决策的翻录。

事实上,由于场地的实际状况各不相同,场地总平面图和最终形成的住宅只是一个框架,用以平衡项目选定的抽象模式语言和真实场地的实际状况。

“事物都有它们自然的和先天的存在方式……现实并不是思维的重新创造。因此,当我们试图探寻真实的意义,我们是在寻找现实,寻找事物真实存在的方式……”

当我设定了项目的模式语言,之后的每一步规划决策,包括房屋在地段中的选址、与道路相联系的入口方向的确定,乃至每个窗户的方位,都是在地段中的分区场地上确定的,并在场地中使用木桩进行标记(图27)。在实际场地中,不可预测的情况接连发生,这也成为设计创新的机遇。

规划过程并非一个不断叠加的过程,而是被视为一个分类提炼的过程。场地中所做的每个决定以及地面上的每个标记,事实上都改变了场地的整体结构。任何阶段中场地所呈现的新的整体结构,都成为下个决定的基础。

场地上呈现的最终“布局”由测绘师记录。根据我的经验,那些有时候在图上看起来不规则和奇怪的决策标示,常常源于场地现实,合情合理,反之亦然。纸上谈兵的、在图纸上看似完美的总平面图,可能在实际场地中却显得莫名奇妙。因此,如果审视“木桩标识的方案”时使人感到疑惑,设计改进的方法是在场地上再次进行检查。最后的“木桩标识的方案”是最终规划设计方案的基础。

在设计之初所作出的决定会影响更大尺度的问题。我们需要在整个设计过程的各个阶段不断进行验证,并关注由最初决定而产生的其他决策。

我们在社区的中心规划了一条主路,分别连接两条道路:一条是滨水的景观道路;另一条是连接 “集体农庄”中心公共食堂和社区之间的道路。

这条道路的路线确定依据是,我希望人们在沿路各处都能看到水景(图28~31)。

房屋以小型组团方式布局,共享一个开放空间。在集体农庄的传统模式中,所有的被称为“草坪”的开放空间都是公用的,房屋任意地散布其间;而在新模式中,次级道路穿行于房屋之间,以这种不使用围栏的非正式方式,划定出每个家庭的“私人”区域(图32)。这种“私人领域感”出人意料地创造出一种新的现实情境,即每个家庭都开始打理自己的花园。在传统模式中,这种新的行为模式并不存在,因为建筑之间的开放空间被当做所有人的共有财产进行使用和维护,事实上不属于任何一个人。

场地中每座房屋的位置都是逐步确定的。设计要思考它们彼此的关系,确保每一个房屋都有面向水面的开敞视野,并能享受从海面吹来的微风(图33、图34)。

为了确定每座房屋的高程,以便人们在露台上就可以看到大海,我坐在一个起重机中,将自己升起到能看到海面的高度。这一高度被记录下来,随之确定了房屋的高程。

6 房屋的设计

图20 / Figure 20

图21 / Figure 21

图22 / Figure 22

图23 / Figure 23

图24 / Figure 24

图25 / Figure 25

图26 / Figure 26

图27 / Figure 27

图28 ——31 / Figures 28-31

至此,场地设计已经完成(图35)。由于住区里每一栋房屋的选址既需考虑与道路的关系,也需兼顾与海的关系,因此不同类型的房屋平面被确定下来。在那些道路入口与海的朝向一致的地方,建筑采用A型平面(图36);在道路入口与海的朝向相反的地方,建筑采用B型平面(图37(a)、图37(b))。

自行车是集体农庄范围内被允许的唯一交通工具,因此每家门前都设有一个自行车架。紧靠入口的门边设置了一处放泥靴子的地方,这是集体农庄的一个明显特征。

建筑墙壁都用浅蓝色的涂料粉刷,辅之以当地的砂岩来塑造建筑细节。

7 美在细节——细节本身并非装饰

一栋建筑整体上美好的秘密,在于它的空间秩序和细节本质。我认为房屋的细节不是一堆设计元素的集合,而是源于秩序语言中的结构性片段,也就是说,每个特定的细节都源自它所从属的更大整体,并对整体有所贡献,且试图去提升整体品质。

震教徒(Shakers)②是18世纪中期的一支宗教教派。当时,他们创造了大量的实用性家具和餐具,认为整体感和美感皆为纯粹功能主义的产物,没有实际功能的美好形式是需要摒弃的。

然而那时,震教徒并没有像现代主义者那样,在词语的狭隘意义上解释“纯粹功能主义”。对现代主义者而言,“形式追随功能”在语义上仅仅与建筑的物质形体相关;而震教徒则从更广义的角度理解“纯粹功能主义”,认为无论在公共开放空间中,还是在建筑室内(图38),其功能与物质形态的体验以及与精神的感受都是密切相关的。

8 现代科技与传统的关系

在城市或自然环境中,保留某个地方的场所精神并不一定意味着其语言的盲目重复。一旦踏入场地中,我的核心问题是:什么是正确的建筑语言,它是否可以促使新设计的当代住区与自然景观进行对话?

环境中建筑强大的表现力,源自它属于环境不可分割的一部分,而不是凌驾于环境之上的人为痕迹。

建筑物的立面和外形确定了公共开放空间的边界,因此也决定了由其引发的感受。

集体农庄的这些房屋和我设计的其他建筑很快引发了一些猜测。其中,有人怀疑这些房屋是否是那些场所中年代久远的历史建筑的“重建”。事实上,如果我设计的建筑让人感觉它们在场地中存在已久,那么我会由衷地高兴。毫无疑问,这种推测是基于我们的常识,即我们身边的新建筑都凸显于周围环境,并且与环境格格不入。因此,人们以为当一栋建筑以一种自然的方式与周围环境有机地融为一体时,它不可能是一栋新建筑。

随后,当人们最终发现这是个新社区时,紧接的疑问是“它属于什么风格?这是否是试图借用旧有建筑语言的新设计?”

我的回答是我并非试图重现历史,或怀旧式地追溯任何风格,我所设计的建筑与历史建筑之间的相似性与关联性在于它们所营造的“家”一般的感觉与体验,这源于我使用了相同的基本模式与设计过程。在过去,这些模式和设计过程是准则,未来也将如此;无论在何种文化和传统中,只要人们想赋予建筑以精神和灵魂,就会运用那些准则。我坚定地认为20世纪30年代后期是“以色列建筑”的消亡期。随着犹太裔建筑师从以色列避难移民到欧洲,欧洲建筑被引入以色列并试图与本土的东方建筑相结合。这一阶段被称为“折衷时期”(图39)。该时期一直持续到20世纪30年代,直到新的“国际风格”取而代之。包豪斯所谓“新时尚”风格被全盘引入以色列,并且与本土毫无联系(图40)。

从本土产生的折衷主义建筑与全盘引入的“国际风格”建筑之间的差别,不能被简单地解释为一种接纳或是拒绝的形态语言。这是两种不同的世界观。换句话说,从折衷主义转换到“国际风格”,尽管建筑在形式上确实不同,但并不只是从一种风格体系转换到另一种。对于这两种不同风格建筑之间的差异,这种简单的区分是不公正的。在折衷时期,建筑师对于门厅、拱门、柱头或是建筑前廊等元素的处理无关风格,只是空间模式的使用。他们深刻地认识到建筑和谐的基本原理,即永恒而跨文化的空间模式。这种空间模式存在于任何美好而舒适的建筑之中,并超越风格。

显然,门厅、拱门、柱头、拱廊或穹顶等空间模式在各个时期的建筑中均可以看到。例如,19世纪末和20世纪初美国建筑师赖特(Frank Lloyd Wright)设计的美丽建筑、14世纪和15世纪奥斯曼帝国时期的亚洲清真寺以及20世纪早期以色列建筑师布劳沃德(Alexander Browald)设计的科学博物馆,等等(图41~43)。

这些模式被现代主义者有意忽略,导致了场所中缺乏情感和意义。

图32 / Figure 32

图33 / Figure 33

图34 / Figure 34

图35 / Figure 35

图36 / Figure 36

建筑和艺术的认同感缺失是一个全球性的现象。北京、纽约、巴塞罗那和以色列特拉维夫所建造的现代建筑毫无差别。同样,毕尔巴鄂的古根海姆博物馆显然不是从西班牙的现实中生长出来的,而是追随潮流的舶来品;迪拜的帆船酒店也是如此。当然,这只是一部分例子。

世界各地都存在着那些独特而永恒的建筑。它们无关乡愁,而是提醒我们,这个世界上存在一种不一样的建筑,值得我们不断关注。特别是在建筑时尚不断随意变化的今天,这更值得重视。

建造具有永恒价值的建筑方法绝不是某些人提倡的那种反当代建筑运动。历史对美的解释并不唯一。相反,我们应充分发挥现代科技社会的潜力,将科技视为一种工具而非目标或价值本身,创造以人为本的友好环境,以满足全体人类的基本需求。这才是真实有益的尝试。特别是当我们的时代提供了无限的可能选择时,科技必须以可控的、以价值观和道德观为导向的方式付诸应用,以设计我们赖以生存的物质环境。

此外,“可持续发展”“绿色建筑”“生态环境”等当前人们习以为常的“标签”,都不再仅仅是节约能源、水、电、回收材料一系列教条准则。本文无意贬低它们的重要性,而是惊奇地发现,所有这些标签都没有关注本应被视为核心的环境因素,即人。这使得建筑看起来像一台机器(至少表面如此),脱离了它们所处的空间环境,也对使用者也极不友善。

环境是为人设计的,可持续发展必须回归到人类身心的基本诉求。对于人类有益的,也必然对环境有益。过去,人类掌控的设计过程的准则来源于日常生活。例如,采用厚的外墙,使房屋保温隔热,减少供暖和空调的需求和花费;根据风、光,以及利用阳台为建筑散热等因素,将窗设置在准确的位置。这些工作的完成不需要任何口号,因为建筑师所关注的全部就是人的体验,建筑正是为此而建造。

本文阐述了对于人类具有普适性的空间模式以及跨越文化、使人类和谐关联的空间准则。文中展现的规划设计过程从结构上对应了其文化、社会受众群体的身份以及每块设计场地的独特性。现行的设计概念与方法对我们赖以生存的人类环境已造成真正威胁。我希望建筑学的整体现象学方法对于这一情况的改变有所贡献。

图37 (a) / Figure 37(a)

图37 (b) / Figure 37(b)

图38 / Figure 38

图39 / Figure 39

图40 / Figure 40

图41 / Figure 41

图42 / Figure 42

图43 / Figure 43

ORIGINAL TEXTS

The aim of this essay is to present my particular interpretation of the holistic-phenomenological worldview in practice, in one selected project I designed and built in Israel. A worldview which stands in recent years at the forefront of the scientific discourse as a whole in disciplines like cosmology, neurobiology, psychology, particle physics and brain sciences, and is linked to recent theories of complexity. As well in convergence with the fundamentals of Buddhist science, the two worlds my work is associated with.

I will demonstrated how this approach, as well as the planning process I follow —— a process fundamentally different from conventional ones ——were implemented in a residential neighborhood I designed in the social, economic and physical structure of the collective known as a “kibbutz”(founded in Israel in the early 20th century). The introduction of a conceptually new model in a very rigid social framework became possible now, as a result of an overall change in the reality of the“kibbutz” communities, a change that was inevitable in the 21st century.

The aim of this essay is to raise broad public discussion regarding central debates concerning the general public and to challenge 21st-century architecture, as to how we should intervene within an existing environment whether urban or natural landscape which we must respect and preserve ——when integrating within it a new contemporary buildings, using the full potential inherited in the modern technological age in which we live.

The definitions given by me in this essay for terms such as “quality” or “assimilation of values for preserving the environment” have a broader meaning than the commonly used ones, as will be discussed in later chapters.

1 Biographical Milestones and the Background for the Growth of the Holistic Approach

I am a practicing architect working in Israel for more than 40 years. My work focuses on both practice and theory, and is tightly connected to the Phenomenological-Holistic School of Thought.

In this chapter I shall present the streams of thought that were evolving in architecture at thetime, including the emergence of the holistic approach. I shall do so by presenting their linkage to the milestones in my “journey” which have most influenced my work in the various creative fields I have been engaged with in general, and in architecture in particular.

These include the various sources of knowledge I have been exposed to during my formal architectural studies; teaching & research work; studies of Buddhism; and most important of all - the place I grew up in, the Cabalist city of Safed,①my heritage and my roots as a seventh generation descendant of a family that has lived in the place since the 19th century (Figure 1, Figure 2).

My curiosity about what lies at the foundation of organic architecture started with my first year as a student of architecture (Technion Institute of Technology, Haifa, Israel) at the end of the 1960s.

I wanted to understand what lay behind those places and buildings that make us feel “at home”, what powered them with so much beauty and soul that make us return to them again and again. I needed to understand the processes by which these buildings were created.

My intuitive feeling was that what lies behind those places and buildings were facts, reasons and objective truth, I wanted to understand and act upon it in my design work.

The mid 1960s were a breaking point in the world of architecture. There was a feeling and consensus that the mechanistic worldview, upon which modern architecture was based on, had gone bankrupt as it did not give any decent answer to the human relationship between man and environment. Places like Brasilia in Brazil, Chandigarh in India, the satellite towns such as Milton Keynes that were built in England during the late 1960s and the 1970s, the new neighborhoods built in Jerusalem post 1967 war were all designed and built adopting the mechanistic approach. One of its founders, apparently responsible for the disastrous outcome that followed from it, was the famous architect Le Corbusier. These alienated places were a clear expression of the lack of an organic order. However the forces that were inherent in modern architecture, like the ones inherent in contemporary architecture, have gained such a strong foothold, that many were afraid (and still are) to express their reservations, and all the more so, to make a change.

The late 1960s and early 1970s brought to the forefront of science in general and architecture in particular the quantitative methodological approach, as presented in Geoffrey Broadbent’s book, Design in Architecture, Architecture and the Human Sciences (John Wiley & Sons 1973). According to this theory, the creative process is a product of quantitative planning methods, where complex relationships between man and his environment are defined by matrixes and formulas. I adopted this logical and systematic working process, which enabled me to identify and separate the various elements of a building required by the program and combine them to a whole. This resulted in plans that at the conventional level were indeed neat, reasoned and coherent. The projects that grew out of this mechanistic methodology met the physical and social needs of their users, but only partially answered their emotional and spiritual needs. In other words, this methodology was not aimed to create buildings with a soul.

The Disappointment of the modernism led to a search for new ways. In the early 1970s I left the Technion and moved to London to continue my studies at the A.A. School of Architecture. I found a school where the main theme in teaching architecture was conceptual. This was in line with conceptual art starting to flourish at that time, first exposed in an exhibition named “When Attitude Becomes Form”, held at the ICA (Institute of Contemporary Arts) gallery in London. It became a landmark in the art world (Figure 3). In discussions held at the time in the A.A school, man’s environment was conceived as a mere metaphor for science fiction, completely ignoring and even belittling anyone who tried to speak about the emotional - human experiential relation between man and place.

This conceptual approach developed, and led later on to the emergence of new movements, each one attempting in its own way to find a solution and a way out of the disappointment and despair brought on by modern architecture. Among them, the “Archigram” in London (based on their theory 15 years later the Pompidou Center was designed by others in Paris), the “Post modernistic” stream—— the “New York Five” on the east coast of the U.S, the “New Tradition” clinging to the past and the “Deconstruction” stream still starring today. These movements, although different from each other, have one thing in common and that is their basic assumption that there is no absolute truth behind architecture and that beauty and comfort are subjective concepts that have to do with style, fashion and the personal vision of the creator. In fact this assumption denied any objective public discussion on the definition of beautiful architecture. Not one of these movements attempted to seriously confront the crisis at hand or make changes in order to resolve it.

In 1973 completing my studies, my first commission was planning the house of the writer David Shutz in Jerusalem. Stone buildings surrounded the site and in the center was a lemon tree.

Unlike the conventional planning process which took place on the board in the office and then transferred to the site, here all planning decisions were taken by me on the site itself. Trying to feel and experience physically what had happened there. The first planning decision I made was to leave the lemon tree in its place and design the house around it. I walked back and forth; I was looking for the boundaries of the patio that would “feel right” ——the actual place on which the walls of the building would be erected (Figure 4, Figure 5). But even in this case, where the house clearly grew out of the reality of its site, there were some critical questions that still remained open:

—— What are the rules and processes that determine the right relationship between the parts of the building in order to create a whole?

—— What is the glue that creates the feeling of unity in a building? In other words, what is the secret of harmony in architecture?

I tried to record and understand the visible structures of those timeless organic places I came across to (Figure 6), using them as a model for the new projects I designed. The unsatisfactory outcome made me understand that no place is self-existent, independent of the unique reality to which it belongs, and that planning a new place with that desired quality, involves not just an application of an existing model, but a deep understanding of the Genetic codes and the processes that lead to its creation.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s I worked with Christopher Alexander at the “Center for Environmental Structure” in Berkeley (a researchinstitute Alexander founded in the mid 1960s and directed since). I became closely familiar with all his research work and participated in the planning of The Cooperative village “Shorashim” in Israel. This experience both in theory and in practice made me understand in a profound and implementable way, the nature of order in architecture and the operational process leading to its creation.

The assumptions put forward by Alexander as early as the mid 1960s were essentially different from those of the movements mentioned before. This was an approach that by its very definition created a lot of reaction. Alexander’s basic assumption was that order and beauty are an objective matter inherent in the structure itself, and that feelings have to do with facts, based on absolute rules that have always determined the quality and beauty of a place (as discussed in details in Chapter 5).

The exposure to the Buddhism logic at a later stage made me understand the foundations of the holistic approach I adopted, trying to implement in the buildings I designed.

The holistic approach (discussed in details in Chapter 3) is a broad and universal approach and is at conflict with the mechanistic worldview ——traditionally more common in the Western world.

However, as I made my way along these paths that marked and enlightened me, I realized that in this journey I was, and the answers to these questions I already had been exposed to. There in my childhood, at my grandmother’s Hotel (Figure 7) she founded 65 years ago in a small stone building at the end of an alley in the old city of Safed and at its alleys as a whole.

This experience had the greatest impact on my understanding how a place should “feel”, and the insight of what is that “Art of making” which creates these places. I got from watching my grandmother preparing the food in her kitchen at her hotel (Figure 8), or whitewashing the walls of the alley in light blue (Figure 9).

I always assumed that my strong emotional attachment to Safed was generated from a subjective experience. But then I realized that other people, who came there from places; cultures and traditions different from mine, had nonetheless a similar experience. That made me understand that something much more basic is happening there —— common to us all as human beings (as discussed in details in later chapters).

2 Architecture is Made for People–Phenomenological Approach to Architecture The purpose of architecture as I see it is first and foremost to create a human environment for human beings. Nevertheless, modern society has lost site of the central value, the human being, and created an environment in which there is a feeling of alienation between man and place.

Buildings affect our lives and the fate of the physical environment in which we live over the course of many years, and therefore their real test is the test of time. The fine old buildings where man feels "at home", the ones we always want to return to (from the past and the present) are thus endowed with a timeless relevance and are the ones that touch our hearts and have the power to release feelings.

Although this timeless quality exists in buildings in different places, rooted in different cultures and traditions, the experience they generate is similar and common to all people, no matter where or from what culture they come from (Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12).

There are different ways to describe buildings that have this timeless quality. Frank Lloyd Wright called them “the ones which take you beyond words”. Quoted by Stephen Grabow: “The buildings that have a spiritual value are a diagram of the inner universe, or the picture of the inner soul”.

The experiential-emotional relationship between people and the community neighborhood —— occurs at all levels of the relationship that exists between man and environment. Manifested at the urban scale, meaning the way the building contributes to the experience taking place in the public space, in the interior spaces of the building and down to smallest details such as light fixtures; furniture; door handle—— the most intimate level between user and place. Contemporary architecture as well as conceptual art sought to dissociate themselves from the world of emotions, and connect the design process to the world of ideas and images, accordingly creating a rational relation between building and man devoid of any emotion. The basic assumption presented here, is that in order to change the feeling of the environment and create places and buildings that we

really feel part of and want to live in, what is needed, is not a change of style, fashion or personal vision of the creator, but an adaptation of a new worldview. A holistic-phenomenological worldview that will transform the ones underlying current thought and approaches which are an existential threat, to the physical and human environment in which we live.

3 Between Two Worldviews —— The Holistic Approach vs. the Mechanistic Approach ——The Relationship between the Parts and the Whole

The difference between the worldview which resulted in dissociating man from his environment and the worldview that considers man to be part of the physical world he lives in (as well as part of nature), emphasizes the difference between the holistic organic school of thought to which my own work belongs to, and the mechanistic-fragmentary worldview. These are two different set of orders.

The mechanistic worldview dominant traditionally in Western thinking and underlying contemporary architecture as a whole separates elements, consequently creating a mechanically-ordered environment of autonomous fragments, the result of which we witness in places like Brasilia in Brazil, Chandigarh in India, the satellite towns in England, or for that matter, the new neighborhoods built in Jerusalem after 1967, where the structured disconnection between the house and the street, the street and the neighborhood, the neighborhood and the city arouses a feeling of detachment and alienation.

The house appears to be a random collection of objects; the street appears to be a random collection (catalogue) of buildings that do not create together a street, often even prefabricated transported units made in a factory and superimposed on the site (Figure 13); the streets do not form together a neighborhood; and the neighborhoods do not create a city.

As opposed to these buildings were the ones designed in traditional villages and cities where by the “unknown” architects or people that what they had in mind was obviously us, the pedestrians strolling in the public spaces. They understood that the responsibility placed on the buildings they designed was the first and foremost to the quality ofthe street, the boundaries of which they define. They understood that urban design does not start and ends by doing arbitrary sketches on a scale of 1:1000 but with being constantly aware of the scale 1:1 of the human being. An experience generated by the sight of the railings of the balcony, the iron bar on a window, and the smell and sight of fruit trees at the entrance courtyards of the houses (Figure 14).

This approach was not understood by Le Corbusier, Oscar Niemeyer and other modernists around the world who were part of the mechanistic school of thought or contemporaries who consciously consider architecture to be no more than icons, environmental installations and fireworks, directly responsible for the disasters we are witnessing in the physical environmental in which we live.

The holistic-organic approach that has been for many years at the forefront of the scientific thought in general, regards the socio-physical environment as a system or a dynamic whole, the existence of which depends on the proper, ever-changing interrelations between the parts (Figure 15). Moreover, the creation and existence of each part depends on the interrelations between that part and the system.

The Buddhist science claims in general, that any entity comes into existence in dependence on other factors and conditions.

That understanding of “dependent arising”, cause and condition, is the condition for the realization of emptiness, which is the foundation of all Buddhist philosophy.

This kind of “subtle impermanence” is confirmed by scientific findings in disciplines that are the result of generations of scientific investigations.

In any organic system while each element has its own uniqueness and power, it always acts as part of a larger entity to which it belongs and which it complements. Having adopted this concept, I regard urban design, architecture, interior design and landscape design not as independent disciplines removed from each other, but as one continuous and dynamic system. Every design detail, at any level of scale, is derived from the larger whole to which it belongs, which it seeks to enhance and for whose existence it is responsible. The overall feeling of inner wholeness and unity whether in a building, a street, a neighborhood or a city, eventually evolves from the proper interrelations between its parts.

This notion led me, at the time I started to design the neighborhood in the “Kibbutz” to think first about the open spaces and not the houses themselves. All decisions regarding the location and the volume of the houses, their height and the material used for its construction were derived from the spirit of the open landscape, meaning from the larger system it was responsible for, had to be integrated with, respect and enhance.

4 Structural Changes in “Kibbutz” Life Require a New Concept of Housing ——from Quantitative Uniformity to Qualitative Equality

The social, economic and physical structure of the collective known as a “kibbutz” was founded in Israel in the early 20th century (Figure 16). Its uppermost value since its very beginning was equality, translated in most realms of community life not as equality of opportunities, in its qualitative sense, but rather in its quantitative sense, as formal uniformity. This dogmatic equality obliterated the self-identity and uniqueness of the individual and saw him only as part of the collective.

In recent years, however, this old conception of equality has been redefined in many respects. The social structure reverted back to the nuclear family, with children raised at home and no longer in a communal house where they were regarded as the possession of the community as a whole. Wages, previously based on the notion that every member contributed according to his or her own ability, but was supported according to his or her needs, have now become differential, based on one’s contribution.

Housing in the “kibbutz” is perhaps the last fortress of the old and simplistic conception of equality, a conception that now more than ever can change. According to this conception, houses are regarded as static models of predetermined uniform shape, arbitrarily positioned on the building site. Environmental factors, such as the direction of light or the angle open to the view on any specific plot, are disregarded, and the result is that all houses have an identical plan, including the same elevations. Thus a tenant whose window happens to face the orchard has the advantage on the one whose window faces the cow shed.

This approach created a qualitative inequality between the houses and inequality of opportunities among the tenants. Moreover, the outcome of this dogmatic approach was that houses built in the desert environment of the Negev district or the hilly Galilean environments were exactly the same.

The new model introduced by me in the design of the new houses in “kibbutz” “Maagan Michael”was fundamentally different. Adapted to the overall change in the reality of the “Kibbutz” communities in Israel in the last two decades.

5 The Planning Process Itself

The approach underlying the design of the neighborhood was that a building must grow naturally from the site on which it is built, and not force itself upon it.

The process by which the planning decisions were taken on the site was preceded by a study of both the quantitative and qualitative needs specified by the community of the “Kibbutz”. These needs were translated into a list of common “patterns”, which abstractly but specifically defined the spatial order of the houses.

The site plan and the layout of the houses developed gradually from the deep interaction between those common patterns and the living reality of the actual site, a reality that differed from site to site.

5.1 The Generative Language of the Neighborhood—— a Pattern Language

In his book The Timeless Way of Building Alexander states that all places of organic order that may seem unplanned and disorderly are actually a clear expression of order on a deep and complex level. This order is based on absolute rules that have always determined the quality and beauty of a place and is the source of the good feeling in it. In other words, there is a direct connection between the pattern of events that occur in a place and the physical patterns —— patterns of space in his terminology —— that constitute it.

More over what stirs in us emotionally in the courtyard in Safed can stir in us at the Hutton’s in Beijing. The quality that stirs in us as we walk an alley in Safed, Israel, can stir in us in Siena, Italy or in Lijiang, China (Figure 17, Figure 18).

An empirical research conducted in the mid 1960sfor over a decade at “The Center for Environmental Structure”, aimed to analyze all those places that share a common pattern of events and feel similar, in order to identify the common element.

Their basic assumption was that just as every substance has a basic component called an atom, the man-made environment consists of “atoms” which he called patterns. Each pattern is an archetype of a structure that repeats itself in an infinite variety, and although its form varies from place to place, there is an underlying structure —— the archetype which remains the same.

So when we come across an African tree we have never seen before, we do recognize it as a “tree”. The reason for that is that the entity we identify as a “tree” is not the visible form, but the underlying structure, the relationship between the parts of a tree. And although form repeats itself in an infinite variety, the pattern of relationship remains the same (Figure 19).

The importance of these patterns, 250 in number as listed in A Pattern Language, lies in the fact that they constitute a system which generates an entire language. It includes patterns from the city scale level to that of individual buildings and construction details. Each pattern in the language consists of other smaller patterns and is at the same time part of a larger pattern. In other words, each pattern is a pattern of relationships. The language is a generative one and the hierarchical order of the patterns it consists of, is determined by the rules of the language itself. What ultimately creates a meaningful city, a street or a house, is similar to what gives meaning to a sentence in the spoken language, which is the syntax.

Since the environment consists of patterns that produce the feeling of comfort we all share no matter what culture or place we come from, which apparently defies cross-cultural boundaries, Alexander’s assumption is, that in the physical space, there are patterns that reflect an innate pattern structured in our brain, same as the notion of the linguist Noam Chomsky, in the various spoken languages defined as the language of languages.

The first step in the planning process in the “Kibbutz”was to determine the patterns of space that were relevant to the project, patterns that grew out both of the social structure of the “Kibbutz”, the geographic location facing the Mediterranean sea, and ones stemming from the basic needs common to us as human beings (daylight is essential for the mental and physical wellbeing whether in a senior citizen’s center or in a kindergarten, whether in India or in Israel). When this list of common patterns abstractly but specifically defined the spatial order of the houses, were used in different site conditions, a variety of houses emerged, sharing one architectural language (Figure 20, Figure 21).

As for example:

—— Entrance “Gate”: One of the first decisions concerning the neighborhood involves the location of the Entrance “Gate” to the site. This location determines the relationship between the new neighborhood and the “Kibbutz” as a whole.

—— South Facing Outdoors: “Place the building to the north of the outdoor spaces that go with them. And keep the outdoor spaces to the south (Sun). Never leave a deep band of shade between the building and the sunny part of the outdoors.” If there was a conflict between the preferable direction of the sea and the direction of the sun, the priorities were weighed on a case-by-case basis (Figure 22).—— Wings of Light: “Arrange the house so it breaks down into wings that correspond to the natural activities within the building. Make each wing so that natural daylight will cover all areas of the house.”

—— Entrance Transition: “Make a transition space between the path (street) and the front door. Mark it with a change of direction, a change of surface…and above all a change of view ( Figure 23).”

—— Main Entrance Door: Once the location of the paths and the built-up areas on the site were marked on the ground, the next search, perhaps the most important one in the evolution of the plan, was for the proper location of the entrance door. “Place the main entrance of the building at a point where it can be seen immediately from the main avenues of approach and give it a bold, visible shape which stands out in front of the house” (Figure 24).

—— Focused “Zen” View: “Where there are particularly beautiful views, do not destroy them by building one large picture window that turns the view into nondescript wallpaper. Special views should be framed and thereby intensified” (Figure 25).

As experience has shown me that placing the window in a deviation of even 10 cm can violate all it is meant to achieve, the precise location of the window can be ascertained only by being on the site itself.

5.2 Planning the Neighborhood on the Site

“Kibbutz” “Ma’agan Michael” is situated on a hill, with the new neighborhood on the western side that faces the sea (Figure 26).

The planning process proposed here was fundamentally different from the common planning processes. Unlike the common planning processes, where planning first takes place in the office and the site plan and the form of the houses is predetermined with no relation to the reality of the site, here the drawings are merely recordings of the planning decisions taken on the site itself.

The plan of the site and the houses that were finally created were actually a structure of balance between the abstract pattern language chosen for the project and the living reality of the actual site, a reality that differs from site to site.

“Things have a natural and innate mode of existence…. Reality is not something that the mind has fabricated anew. Therefore, when we search for the meaning of truth, we are searching for reality, for the way things actually exist….”

Once I set the list of patterns for the project, each planning decision, from the positioning of the house on the site, through the determination of the direction of its entrance in relation to the path, and unto the location of each window, was taken on the site of each plot, literally marked on the site with wooden stakes (Figure 27).

The unpredictable conditions that were continuously developing on the actual site, created openings for new things .

The planning process is not conceived as an additive, but rather as a differentiating one. Each decision taken on the site and marked on the ground actually changed the configuration of the site as a whole. The new whole fully visualized on the site at any stage, formed the basis for the next decision.

The final “layout” that emerged on the site was recorded by a surveyor. Experience has taught me that decisions which may sometimes appear irregular and strange on paper, often make sense in reality (where it comes from), and vice versa. A plan that appears perfect on paper (where it was created) may seemsenseless on the site. So, if when looking at the “stakes plan” doubts arise, the correction is checked again on the site itself. The final “stakes plan” forms the basis for the final plan.

Decisions are first made on issues that affect the larger scale we have to confront at any given moment along the process, moving to other decisions generated from them.

At the center of the neighborhood, a path was planned connecting the promenade that runs along the water and the path that runs from the communal dining hall at the heart of the kibbutz to the neighborhood.

What dictated the course of the path was my wish to see the water from every spot along the path (In sequence left to right Figure 28 - Figure 31).

The houses were arranged in small clusters, sharing a communal open space. Unlike the traditional pattern in the kibbutz, where all open spaces, called“the lawn”, are communal and the buildings are dispersed arbitrarily in between, here the secondary paths running between the houses defined in a nonformal way, with no fences, the “private” zone of each family (Figure 32). This sense of “private territory” unexpectedly created a new reality in which each family started to grow its own garden. This new pattern of behavior could not have developed in the traditional model, where the open spaces in between the houses were planned as a property used and maintained by everyone, and therefore of no one.

The position of each house on the site was done in a piecemeal process, in relation to the others so as to ensure that each one has an open view to the water and can enjoy the breeze coming from the sea (Figure 33, Figure 34).

To determine the level of each house so that one could see the sea while sitting on the terrace, I used a crane to lift me up to where I could see the sea. This height was measured and the level of the house was determined.

6 The Design of the Houses

At this stage the site plan was completed (Figure 35). The location of each house in the neighborhood in relation to the paths and its position in relation to the sea produced different types of house plans. On plots where the entrance from the path was in the same direction as the sea view, type A plan emerged (Figure 36). On plots where the entrance was from the opposite direction of the sea view, type B plan developed (Figure 37).

In front of each house there is a bicycle rack (the only means of transport allowed within the boundaries of the kibbutz). Next to the entrance door a place for muddy boots was allocated, a prominent symbol of the kibbutz.

The walls are all whitewashed light blue, complemented by regionally quarried sandstone characterizing the construction details.

7 The Beauty Is in the Detail —— the Detail Is not an Ornamental for Its Own Sake

The secret concealed within the beauty of a building as a whole lies in its spatial order and in the nature of its details. I do not perceive the details of a building as a collection of designed elements but as a structural segment derived from a hierarchical language in which each specific detail is derived from the larger whole to which it belongs, for whose existence it is responsible, and which it seeks to enhance.

The Shakers, a religious sect that created an abundance of useful furniture and utensils in the mid-eighteenth century, noted that the wholeness and beauty of form are products of pure functionalism, and that there is no room for beautiful forms that do not flow from a functional need.

At the same time however, the Shakers did not interpret the term “pure functionalism” in the narrow sense of the word as did the modernists, for whom the expression “form follows function” was semantically connected only to the physical body of the building. They understood it in the broad sense, connecting it both to the physical and spiritual experience one feels whether in a public open space or inside a building (Figure 38).

8 The Relationship between Modern Technology and Tradition

Preserving the spirit of a place (urban or natural) does not necessarily mean a fanatic repetition of its language. The key question I asked myself while standing on the site was what would be the right language that would create a dialogue between the new contemporary neighborhood I designed and the natural landscape.

The powerful presence of the building in the environment emanates from it being an integral part of it, and not from the efforts to be distinguished.

The dimensions and façade of the building define the boundaries of the public open space, and therefore determine the feeling it inspires.

One of the assumptions that immediately arises regarding the houses (as well as with other buildings I design), whether they are “reconstruction” of buildings of the past that had stood there much before. The fact that it feels as if it has been on the site forever, makes me feel good. This assumption is based without any doubt, on the new buildings we see around us that “bark” at their surroundings and being alien to it. Consequently people assume that a building that is organically integrated in a natural way with its surroundings cannot possibly be a new building.

Furthermore, when finally discover that the neighborhood is in fact new one, the next immediate questions I am asked in reaction is “to what style does it belong? Is it a new design that tries to reconstruct an architectural language from the past?”My answer to that is that I do not attempt to reconstruct the past or to nostalgically trace any style. The similarity and the association created between the buildings I design and those we know from the past, and the similar experience and feeling of “a home” they create, originate in my use of the same fundamental patterns and design processes that were the guidelines in the past, and will continue to be so in the future, in any culture and tradition, where people aspire to give a building spirit and soul. I would confidently argue that late 1930s was the end of identified “Israeli architecture”, when European architecture was brought to Israel, carried out by Jewish refugee architects who immigrated to Israel from Europe, trying to become integrated with the local oriental architecture —— thus named the“Eclectic period”(Figure 39). This lasted until the 1930s when the new “International Style” took over, the Bauhaus, a style that was the “dernier cri”, that was imported to Israel as a package deal in no way related to the place (Figure 40).

The difference between the imports of an International style as opposed to the emergence of the Eclectic architecture from within the place, cannot be explained in the common simplistic way as an adaptation or the rejection of a formallanguage. These are two different worldviews. In other words, the transition from Eclectic architecture to “International Style”, which truly appears different in form, is not a shift from one stylistic principle to another. Such a distinction does an injustice to the difference existing between these two styles of architecture. The use of patterns such as entrance hall, arches, column capitals, or an arcade at the front of a building by architects in the Eclectic period, was not a matter of style. They understood in a most profound way what are the fundamentals of harmony in architecture —— the timeless crosscultural patterns which underline the beauty and comfort in any building that transcends styles.

Evidently these patterns such as entrance hall, arch, a capital in the column, arcade or a dome, can be found in buildings of all periods: in the beautiful buildings designed by the architect Frank Lloyd Wright during the late 19th and early 20th century in the United States; in the mosques built in the Ottoman period in the 14th and 15th centuries in Asia and in the Science Museum designed by architect Alexander Browald during early 20th century in Israel ( Figure 41, Figure 42, Figure 43). These patterns were on purpose ignored by the modernists, resulted in places devoid of any emotions and meaning.

The loss of a sense of identity in architecture and art is a worldwide phenomenon. There is no difference between contemporary buildings built in Beijing, New York, Barcelona or Tel Aviv. The same provinciality which led to the creation of the superimposed Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao which was certainly not generated by a Spanish reality, or to the Burj Al Arab Hotel in Dubai. This of course is only a partial list.

The unique timeless architecture worldwide is not a matter of nostalgia, but a reminder that there is a different kind of architecture we must pay attention to over and over again. Especially at a time when buildings are created according to ever changing and arbitrary fashions.

The architectural approach which aims at fulfilling timeless values is by no means a reaction against the contemporary movement as one might think. The past has no monopoly on beauty. On the contrary, it is a genuine attempt to fully use the potential inherited in modern technological society available today, not as an aim or a value in itself, but as a tool to create a human and friendly environment that will satisfy the basic needs common to all of us as human beings. Especially at a time where unlimited possibilities are open to us, technology should be used in a controlled, value-oriented and moral way when approaching the design of the physical environment in which we live.

Moreover, the “trademarks” we have become accustomed to and which are currently used as“sustainable development”, “green building”,“ecological environment” and the likes, are no more than a list of dogmatic rules that refer to the saving of energy, water and electricity and the recycling of materials. Without reducing their importance, surprisingly there is no reference at all in the list to what should be considered as the central environmental resource —— the human being. This results in buildings that look like machines (to say the least), and which are alienated to their physical environment and far from being friendly to their users.

“Sustainable development” must call for the basic needs (body and soul) of the human being for whom the environment is being built. What is good for the human being will necessarily be good for the environment. In the past, the rule of thumb dictated design processes generated from the daily experience. For example the use of thick walls to isolate houses from heat and cold reduced the need (and cost) of heating and air-conditioning; so did the attention put on the exact location of windows in relation to wind and light and the use of wind balconies to cool down the house. The work was done without slogans, because what filled the architect’s vision was the human experience for which the building was made for.

I hope that by presenting an approach which tries both to identify the patterns (needs) common to us all as human beings, codes that cross cultures and link us together in harmony, and by applying a planning process which structurally responds to the identity of each cultural and social group we build for, and to the uniqueness of each site, I will contribute something towards replacing current conceptions and approaches that forms a real threat to the physical and human environment we live in.

注释

Notes

① 萨法德城,早在第二神庙时期有数万犹太人因害怕宗教裁决从西班牙和葡萄牙逃入,在16世纪成为以色列犹太社区最重要的精神中心。很多居住在那里的犹太人都是宗教法规和犹太哲学的学者和神秘主义者,包括拉比·比约·哈伊(Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai),他被认为是《光明篇》(Zohar)的作者,《光明篇》是犹太哲学最重要的文本之一;还有拉比·约瑟夫·卡罗,《律法》(Shulchan Aruch)的作者。

The city of Safed, dated to the period of the second temple and haven to thousands of Jews who fled from Spain and Portugal in fear of the Inquisition, became in the 16th century the most important spiritual center of the Jewish community of Israel. Many of the Jews who settled there were prominent mysticists and scholars of religious law and Kabala, including Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai, who is thought to be the author of the Zohar, one of the most important Kabalistic texts, and Rabbi Joseph Karo, author of Shulchan Aruch (code of laws).

② 基督再现信徒联合会(United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing),1774年由安·李(Ann Lee,1736——1784年)建立,现已基本消亡。震教徒的赞美诗、灵歌、舞蹈等祈祷音乐非常著名。——译者注

[1] Christopher A, Sara I, Murray S. A pattern language [M]. New York: Oxford University Press, 1977.

[2] Christopher A. The timeless way of building [M]. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979.

[3] Stephen G, Christopher A. The search for a new paradigm in architecture [M]. Boston: Oriel Press, 1983.

[4] Portugali N. The act of creation and the spirit of a place: a holistic-phenomenological approach to architecture [M]. Stuttgart / London: Edition Axel Menges, 2006.

[5] Portugali N. A holistic approach to architecture: the Felicja Blumenthal music center and library, Tel Aviv [M]. Tel Aviv: Am Oved Publishers Ltd, 2011.

摄影 / Photography:Amit Geron, Nili Portugali文字输入 / Computer work:Lili Leikind

水彩插图 / Watercolor painting:Gleb Shebaleb

A Holistic-Phenomenological Approach to Architecture A Case Study: Residential neighborhood, “Kibbutz Ma’agan Michael”, Israel

Nili Portugali

Translated by CHEN Jinxi, YAN Shaoning; Proofread by YANG Tao

The aim of this essay is to present my particular interpretation of the holistic-phenomenological worldview in practice. I will demonstrated how this approach, as well as the planning process I follow —— a process fundamentally different from conventional ones —— were implemented in a residential neighborhood I designed and built in the social, economic and physical structure of the collective known in Israel as a “kibbutz”.

Holistic; Phenomenology; Design methodology; Pattern language; Community neighborhood

2015年9月19日

希望能引起一场广泛而公共的对21世纪建筑的讨论和挑战,我们应该如何以一种道德和人道的方式介入我们必须尊重和保护的现有环境,并将新的现代建筑融入其中。

Hopefully raising a broad public discussion and a challenge to 21st-century architecture, as to how we should intervene in a moral and human way within an existing environment which we must respect and preserve —— when integrating within it new contemporary buildings.