The Accountable Care Organization results: Population health management and quality improvement programs associated with increased quality of care and decreased utilization and cost of care

2015-12-06RonaldDonnellNishantShaunAnandCarolineGanserNancyWexler

Ronald O'Donnell, Nishant Shaun Anand, Caroline Ganser, Nancy Wexler

1. Arizona State University,College of Health Solutions,500 N. 3rd St., Phoenix, Arizona 85004, USA

2. Banner Health Network, 1441 N. 12th St., Phoenix, Arizona 85006, USA

3. Ambulatory Clinical Performance Assessment and Improvement, Banner Health,1441 N. 3rd St., Phoenix,Arizona 85006, USA

4. University of Arizona Health Plans, Banner Health Network,500 N. 3rd St., Phoenix, Arizona 85004, USA

The Accountable Care Organization results: Population health management and quality improvement programs associated with increased quality of care and decreased utilization and cost of care

Ronald O'Donnell1, Nishant Shaun Anand2, Caroline Ganser3, Nancy Wexler4

1. Arizona State University,College of Health Solutions,500 N. 3rd St., Phoenix, Arizona 85004, USA

2. Banner Health Network, 1441 N. 12th St., Phoenix, Arizona 85006, USA

3. Ambulatory Clinical Performance Assessment and Improvement, Banner Health,1441 N. 3rd St., Phoenix,Arizona 85006, USA

4. University of Arizona Health Plans, Banner Health Network,500 N. 3rd St., Phoenix, Arizona 85004, USA

Objective:The Accountable Care Organization (ACO) model of health care delivery is based on new payment models for general practice to reward improved quality and decreased cost of care.Methods:Banner Health Network (BHN) is one of the original CMS Pioneer ACO programs and implemented a comprehensive disease management program based on the collaborative care model. Key performance indicators for CMS reflected quality and cost of care.Results:BHN has demonstrated both improved quality and cost savings in the first two years of the pilot program. The disease management program based on the collaborative care model appears to have improved patient health outcomes based on quality improvement measures. In addition the program has reduced emergency department and hospital utilization, resulting in cost savings.Conclusions:The BHN quality improvement program is the platform for analyzing and improving on the BHN ACO model. This model appears to have excellent application to the China health care system that is also focused on prevention and improvement of chronic disease and cost-effectiveness.

Accountable care organization; population health management; patient centered medical home; disease management; quality improvement

Introduction

Chronic, non-communicable diseases now account for an estimated 80% of total deaths and 70% of total disability-adjusted life-years(DALYs) lost in China [1]. The ageing of the population is one major force driving the epidemic of chronic diseases [2] and is predicted to produce a 200% increase in deaths from cardiovascular disease in China between 2000 and 2040 [3]. The second major force is unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, such as tobacco use, unhealthy nutrition, and physical inactivity leading to obesity [4, 5]. The percentage of ideal cardiovascular health in Chinese adults is extremely low [6]. Abdominal obesity is a major risk factor for diabetes in China [7]. The pooled prevalence, awareness,treatment, and control of diabetes mellitus were 6.41%, 45.81%, 42.54%, and 20.87%,respectively [8]. The pooled prevalence,awareness, treatment, and control were 42.6%, 34.1%, 9.3%and 27.4%, respectively [9]. The cumulative economic loss from the effects of heart disease, stroke, and diabetes on labor supplies and savings over the period 2005–2015 was approximately $556 billion [10]. The prevalence of major depression in China was 11.3% and <1% of these patients received treatments. Greater than 60% of patients with major depression at baseline remained depressed throughout the 12-month followup period [11].

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) is designed to improve the prevention and management of chronic disease by the transformation of primary care from a fee for service, acute care model to a new system in which payment is based on quality,outcomes, and efficiency [12]. The ACA is focused on achieving the "triple aim" of improved patient experience of care(e.g., satisfaction and access), improved population health by targeting high-risk patients for treatment and decreased cost of care by reducing utilization of services, such as emergency department visits and hospitalizations that result from lack of evidence-based treatment [13]. The ACA focus on the triple aim has incorporated new models of primary care, the Patient-centered Medical Home and the Accountable Care Organization, designed to improve patient experience of care,population health, and reduce the cost of care [12].

The Patient-centered Medical Home (PCMH)

The "Patient-centered Medical Home" (PCHM) model was introduced in 2007 [13]. The PCMH model is based on a fully integrated care team for the delivery of primary care services,led by the primary care physician (PCP). The PCMH model of care is aligned with person-centered, coordinated, continuous, and comprehensive service delivery, addressing a person's whole health care needs in a culturally competent manner. The development of PCMH concepts and integrated health care services has decreased the delivery of fragmented care and demonstrated improved patient satisfaction and health outcomes, all while decreasing costs, thus ensuring the commitment and attainment of the triple aim [12]. To succeed, these models must establish integrated care teams of health professionals, care coordination, information sharing, and health information technology for quality improvement and tracking of service delivery [12].

The PCMH model is based on the premise of comprehensive, integrated care coordination, and service delivery while maximizing health outcomes [14]. Although not clearly defined by PCMH, the care team is typically described as a partnership, comprised of the patient, the patient's family and/or support network, a personal physician (PCP), mid-level medical professionals, nursing staff, medical assistants, and behavioral team members (inclusive of behavioral health, case managers, dieticians, and/or health coaches). This team advocates for and supports the patient in receiving high quality,coordinated care from a variety of medical and health professionals working to the full extent of their training. In addition,this expansion to team-based care assists and encourages medical practices to develop and expand the roles of other medical staff members, such as front-office staff to assist in the role of population health management and care delivery.

The Accountable Care Organization

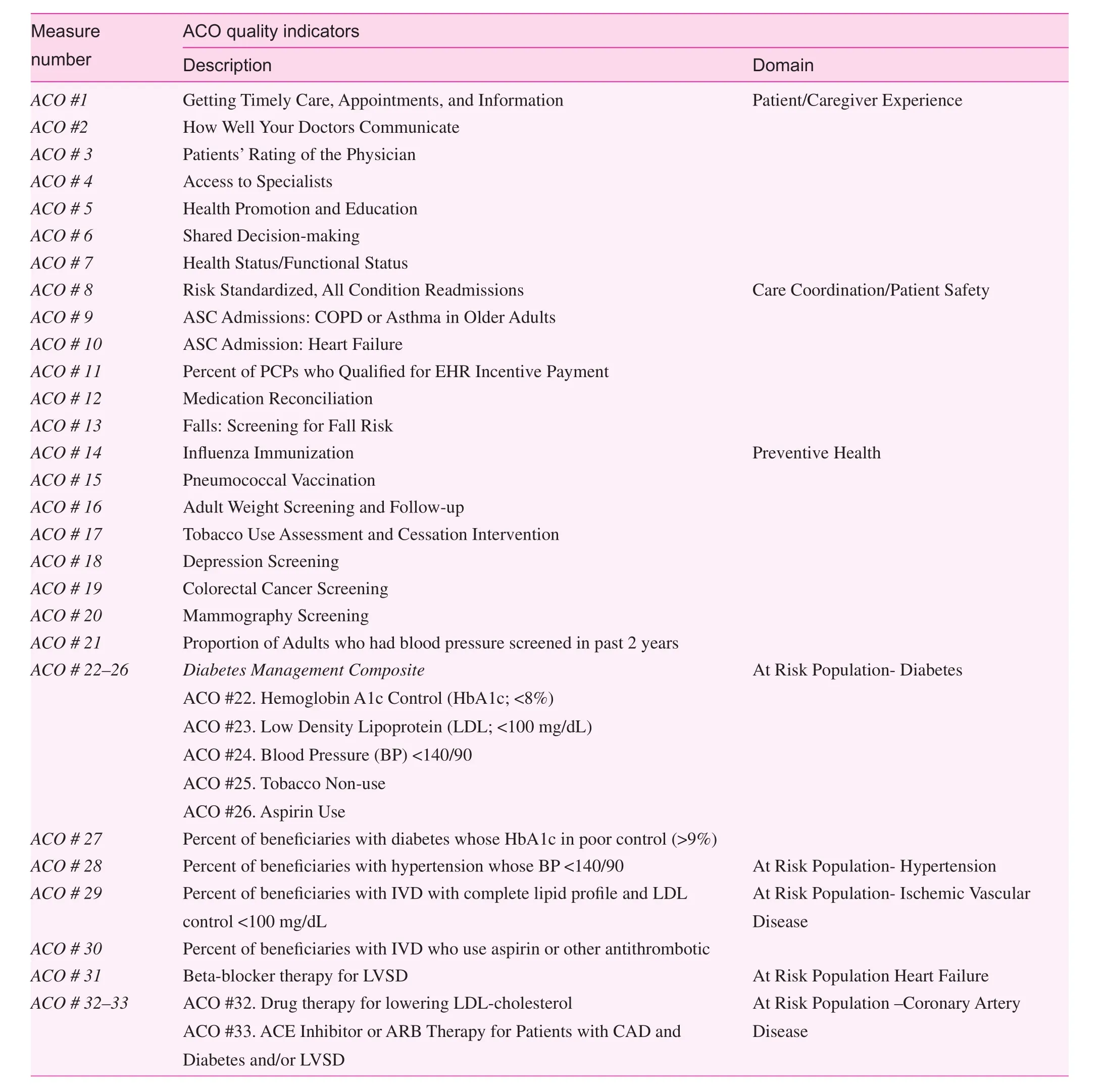

In the Medicare Pioneer Accountable Care Organization(ACO) model, participating primary care provider groups are eligible to receive a financial incentive for demonstrating reduced or slowed growth trends in health care expenditures and improving the quality of care. All of the primary care organizations that join the ACO agree to share cost savings and losses. Savings (or losses) are determined by calculations based on initial benchmark costs based on per capita spending for patients retrospectively assigned to each ACO. These benchmark calculations are based on inpatient and outpatient expenditures over a 3-year period prior to the ACO contract and are updated annually based on overall cost growth nationwide [12]. The ACOs that achieve spending levels below Medicare targets are eligible to receive a share of the cost savings. If spending exceeds the targets then the ACO must return a percentage of the excess to Medicare. Shared savings are based on meeting CMS ACO quality performance standards in four key domains: 1) patient/caregiver experience of care;2) care coordination; 3) preventive health; and 4) at-risk population measures [12] (Table 1).

The evidence

Recent research is beginning to show consistent improvements in quality, outcomes, and cost of care consistent withthe triple aim. A recent review by the Patient-centered Primary Care Collaborative [15] surveying 28 studies between 2013 and 2014 found improvements in cost for 17 of the studies,improvement in utilization in 24, quality improvements in 11,improved access in 10, and improved satisfaction in 8. Wang et al. [16] reported that PCMH reduced overall medical costs for patients with diabetes by 21% in year one, largely driven by reduced inpatient utilization, compared to non-PCMH settings.

Table 1. CMS ACO quality indicators and domains.

A study by van Hasselt et al. [17] showed that PCMH practices demonstrated significant declines in total payments, acute care payments, and emergency room visits after PCMH certification. The decline was greater for practices with sicker than average patients. Higgins et al. [18] found no significant differences in cost or utilization between PCMH and non-PCNH practices for the overall population, but did find significant cost decreases for the patients at highest risk, concluding that the most benefit can be achieved by targeting these patients.

A report on the economic impact of integrated medical and behavioral health care [19] showed that patients with medical and behavioral co-morbidities had significantly higher costs than patients with medical conditions alone. The costs for comorbid medical and behavioral conditions can be 2–3 times higher than patients with a medical condition alone. Most of these higher costs are attributable to medical care, not behavioral services. The authors concluded that increased integrated medical and behavioral care nationally could produce $26–$48 billion in potential savings through reduced hospitalizations and emergency department visits [19].

Population health management and the Collaborative Care Model

The emerging approach to chronic disease management is the population health management-based Collaborative Care Model (CCM) [20]. The CCM is a principle-guided approach to preventing and treating chronic disease comprised of five components: 1) interdisciplinary team-based approach to care;2) patient engagement and activation; 3) structured patient assessment, stratification, and treatment; 4) long-term scheduled patient follow-up; and 5) enhanced care coordination. A hallmark of the CCM is that integrated health care (multiple medical and behavioral conditions, such as diabetes, hypertension, and depression) are all treated simultaneously.

An example of the CCM is an integrated health intervention to manage depression, diabetes, and coronary heart disease [21]. The 12-month intervention combined support for patient self-management skills for their chronic diseases with pharmacotherapy to control depression, hyperglycemia,hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. Patients work collaboratively with nurses and general practitioners to establish clinical and self-management goals. The nurse case manager is the key point contact, meeting the patient in the clinic every 2–3 weeks in the early phases. As the patient makes progress, the nurse makes a transition to telephone follow-up in the maintenance phase.

"Treat to target" pharmacotherapy protocols are used to guide adjustments of medicines in patients who did not achieve specific goals [22]. This involves setting objective target treatment goals (blood pressure, HbA1c, and depression scores) and closely monitoring progress towards the goals over the course of treatment. The nurse uses motivational interviewing and helps patients solve problems and set goals for improved medication adherence and self-care (e.g., nutrition, exercising and self-monitoring of blood-pressure, and glucose levels). Patients receive self-care materials, including a depression handbook and materials on chronic disease management, and self-monitoring devices (e.g., blood-pressure or blood glucometers).

Once the patient achieves initial target levels for measures, the nurse and patient develop a maintenance plan that includes stress reduction, continued work on nutrition, and physical activity goals and medications. The plan includes identification of prodromal symptoms that are warning signs of relapse or worsening, such as increased depression or poor glycemic control. The nurse calls the patient every 4 weeks during the maintenance phase to assess depression, as well as patient goals, adherence, and laboratory test results. Patients with disease control that worsens are scheduled for follow-up clinic visits or telephone calls and the treatment intensity is increased based on the protocols [21].

Compared with treatment as usual controls, patients in the intervention group had greater overall 12-month improvement in HbA1cs, LDL-cholesterol levels, systolic blood pressure,and depression scores. Patients in the intervention group also were more likely to have one or more adjustments of insulin,antihypertensive medications, and antidepressant medications.Patients had better quality of life and greater satisfaction with care for diabetes, coronary heart disease, and depression [21].This model of collaborative care has been applied to many other medical and behavioral conditions, such as anxiety,pain, insomnia, and bipolar disorder, with similar evidence for greater effectiveness than treatment as usual groups and evidence for reduced medical utilization and cost savings [23].

The CCM model often incorporates group education and skills-building groups for improved nutrition, physical activity, and stress management. The groups include structured education and skills-building activities designed to help patients lose weight by improving nutrition and physical activity. Patients complete written exercises in the group and are assigned take-home activities. Patients use a log to selfmonitor daily nutrition, physical activity, and weight. Progress is reviewed in each group session. Often an ongoing support group is offered for patients who complete the basic group sessions. There are many standardized group programs, such as the Dietary Approach for Stopping Hypertension (DASH) diet[24] and the Diabetes Prevention Program [25] that have been adopted for primary care and the Chinese population [26, 27].In addition to efficiency, groups have the added advantage of other patients offering peer support that can enhance and sustain patient motivation.

The Banner Health Network ACO population health management model

The Banner Health Network (BHN), an integrated delivery system in the Phoenix, Arizona metropolitan area, is one of the original 32 pioneer ACO organizations selected by CMS in 2012. This ACO coordinates care within the Banner Health system and among >3000 network providers using a population health management model.

The BHN leadership developed a comprehensive model of population health consistent with 6 key components of integrated care: 1) apply evidence-based care and treatments;2) define, measure, and systematically pursue desired outcomes; 3) use proactive onsite care teams; 4) match professional expertise to the need for treatment escalation inherent in stepped care; and 5) use cross-disciplinary care managers in assisting the most complicated and vulnerable [28]. The key components of the BHN model also include the 5 CCM components: 1) patient identification; 2) stratification; 3) patient engagement; 4) stepped-care interventions; 5) systematic follow-up; and 6) outcomes evaluation.

Patient identification includes 4 critical components: 1)an electronic medical record; 2) a predictive modeling algorithm for identifying high-risk patients based on EHR data,such as diagnoses, services, and utilization; 3) a health risk assessment (HRA) designed to screen patients for cardiovascular and behavioral risk factors; and 4) outcomes data that can be reported to stakeholders based on quality improvement feedback loops.

The BHN algorithm results were used for patient risk stratification to classify patients as low, medium, and high risk for cardiovascular disease and metabolic disorders. Examples include number of medical and behavioral conditions, severity indicators, and utilization history. Stratification is used to classify patients along a continuum of risk, acuity, and chronicity,which in turn are used to develop stepped care interventions.The current focus is on patients at high and moderate risk,with an emphasis on diabetes. The results of the algorithm are shared with the PCP and care managers (typically nurses) and the rest of the primary care team.

The care manager then conducts outreach to contact and engage the patient in the program. Patient engagement is the active process of inviting the patient to enter a treatment agreement based on principles of patient-centered care and shared decision-making. Patient motivation to initiate or sustain treatment is often low, and the use of techniques designed to identify and increase motivation, such as motivational interviewing. Patient-centered care and shared decision-making involve the health professional working collaboratively with the patient to select interventions.

Stepped care interventions are delivered by the care manager based on the patient level of acuity. Patients may be seen initially in the office for an in-person updated assessment and also to develop a trusting, collaborative relationship with the care manager. In addition, the care manager uses a shared decision-making model to develop a treatment plan based on the results of the assessment and recommendations and the patients' perspectives. The plan typically includes medication adherence, improvements in nutrition and physical activity,and development of community-based support. Behavioral conditions such as depression, anxiety, and substance abuse disorder are often identified, and are also integrated into the treatment plan. The care manager is focused on coordination of care to insure that the primary care team is closely aligned with specialty providers

Systematic follow-up is the proactive monitoring of patient progress from initial engagement and acute treatment to the maintenance phase. This is one of the most critical, yet overlooked components of the CCM model because the evidence for cost-savings is based on at least 12 and up to 36 months of systematic follow-up. This period of time is necessary to achieve sustained patient condition self-management in which the patient learns to monitor and modify biometrics, behavioral health status, nutrition, physical activity, and other target behaviors. This should not be surprising; the typical patient has to manage medical treatment regimens, stress and behavioral conditions, and lifestyle behavior changes. The process of learning to manage multi-conditions and achieve condition self-management typically requires months or even years of education and effort, often with health coaching.

BHN ACO financial results

As reported by L & M Policy Research Evaluation [29] of the pioneer ACO Year One spending trends, BHN was among eight ACOs that contributed significant reductions in Medicare spending growth as compared to local markets, equaling a total estimated $155.4 million. Further, BHN was a top performer and one of the two ACOs that accounted for nearly 41% of the total 2012 spending reduction, dropping the per member per month (PMPM) rate by $50.00, as compared to an average ACO decrease of $20.00. While most of the top ACO reductions were reported in the areas of outpatient and physician services,BHN was one of four demonstrating significantly lower spending growth in the inpatient arena. Additionally, while skilled nursing facility and home health service spending increased on average for nine of the pioneer ACOs, the BHN was one of three that observed slower spending growth in this area.

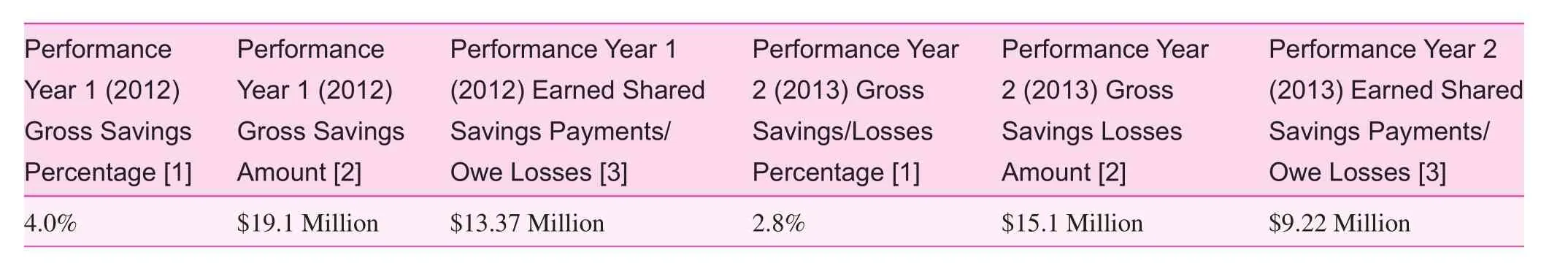

The applied outcome analysis compared ACO spending to local market trends as well as comparing expenditures to a CMS shared savings benchmark. The BHN was one five ACOs that achieved both significant reductions in spending and attained the shared savings target. In year one, BHN reported 4.0% lower medical expenditures than projected for the population of aligned beneficiaries, equating to $19 million in gross savings and a $13.4 million gain share from CMS. In the BHN ACO second year, a 2.8% reduction produced a $15 million gross and $9 million in shared savings (Table 2).

The BHN quality improvement program

The BHN Ambulatory Quality Management team formed in late 2012. The initial focus of this team was raising awareness of the pioneer ACO measures and documentation requirements. The team created an informational presentation and supplementary reference materials about the pioneer ACO and the performance measures.

Site visits to primary care practices started early in 2013.The purpose of the site visit was to serve as a resource and establish a working relationship with the practice, provide information about prevention and chronic disease management performance measures, and evaluate potential for workflow improvements to support care delivery to ACO members.The team also provided regular updates to physician groups and office manager gatherings.

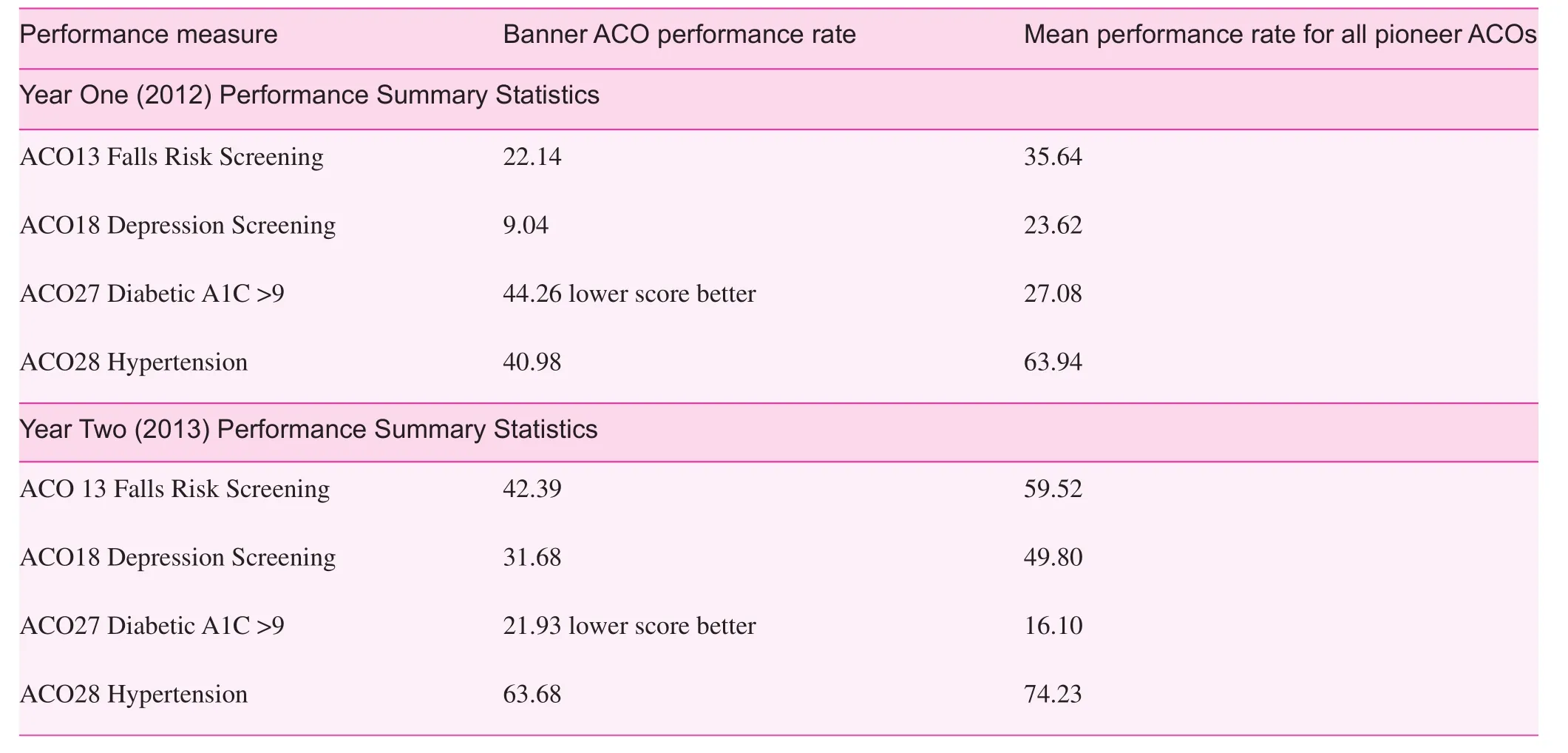

In 2013 a strategic initiative was launched. The purpose of the initiative was to utilize ACO measures to monitor and continuously improve clinical outcomes with the goal of achieving a predictable high quality patient experience and lower health care costs. Baseline data identified three potential areas for improvement: the Diabetes Composite; Adult Weight Screening; and Depression Screening. Monthly sampling of ACO data was collected to serve as an on-going indicator of progress towards target performance. An initiative oversight team, consisting of a BHN physician and clinical leaders, met regularly to evaluate performance and determine improvement priorities. As a result of these focused efforts,the initiative exceeded its target. Pioneer ACO performance improved on nearly every metric from 2012 to 2013. The BHN ACO achieved results in the quality-related measures identified by CMS as important health indicators, such as timely and appropriate care, preventive screenings, and management of chronic disease [30]. The 2013 quality score increased by 19% over the prior year. Table 3 below demonstrates measures achieving the greatest year-over-year improvement.

Table 2. Banner Health Network Pioneer ACO model financial results for years 1 and 2

Conclusions

The BHN population health management program, which was based on the PCMH model and the pioneer ACO reimbursement structure, achieved significant cost reductions and shared savings incentives. The comprehensive quality improvement initiatives resulted in significant improvements on targeted outcomes. The combination of population health management programs based on the CCM, combined with quality improvement programs to educate and support providers on these new models, seem to be critical ingredients to the success of the BHN. The population health management model constitutes the clinical strategies and techniques that lead to effective patient identification, engagement, and continuation in follow-up with the care manager. The BHN results are similar to other recent studies showing that high-risk patients are the best group to target to achieve cost savings.

The quality improvement program serves three critical roles. First, the many meetings and presentations to impact physician groups were designed to provide education on the pioneer ACO model, the costs and benefits of joining, and ongoing training and technical support to maintain the program. Second, the quality program combined with the health information technology department provided the infrastructure for integrated program performance metrics into the electronic health record (EHR) to develop routine performance reports. Third, these performance metrics were integrated into a continuous performance improvement program with techniques, such as process engineering, to evaluate the program and make changes designed to improve performance.

The emerging research on the success of the PCMH and p ioneer ACO in achieving the triple aim has important implications for the health care system in China. It appears that most hospitals and clinics are still based on traditional fee for service models that are designed for acute care, not prevention and disease management. Integrated health services arelacking and physicians focus primarily on pharmacology for treating chronic disease. Lifestyle behavior change treatment in areas, such as nutrition, physical activity, and tobacco smoking cessation, is typically not readily available. The general practitioner often has only basic nursing support and the position of "behavioral health consultant" does not exist in China health care. While physicians and nurses can make incremental steps towards integrated care, these are likely to be insuffi-cient to achieve broad transformation across the entire Chinese health system. It appears that a significant change in the model of health care delivery will be necessary to transform China general practice, just as was required in the United States. The PCMH, team-based, population health management programs have been evaluated and found effective in Chinese research.Most Chinese hospitals and clinics are adopting the EHR and will have the capacity to develop the infrastructure necessary to support these initiatives. In conclusion, the opportunity to translate these emerging practices to China is great,and evidence indicates that if systematically adopted China will have a tremendous opportunity to achieve the triple aim of improved patient experience of care, improved population health, and decreased cost of care.

Table 3. BHN select ACO performance measures for years 1 and 2

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

1. Strong K, Mathers C, Leeder S, Beaglehole R. Preventing chronic diseases: how many lives can we save? Lancet 2005;4:1578–82.

2. Mathers CD, Lopez AD, Murray CJL. The burden of disease and mortality by condition: data, methods and results for 2001. In:Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJL,editors. Global burden of disease and risk factors. New York,USA: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 45–240.

3. Leeder S, Raymond S, Greenberg H, Liu H, Esson K. A race against time: the challenge of cardiovascular disease in developing economies. New York: Colombia University; 2005.

4. Xu F, Ware R, Tse LA, Wang YF, Wang ZY, Hong X, et al.Joint association of physical activity and hypertension with the development of type 2 diabetes among urban men and women in mainland China. PLos One 2014, (published online 9(2):e88719.DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0088719).

5. Sun J, Buys NJ, Hills AP. Dietary pattern and its association with the prevalence of obesity, hypertension and other cardiovascular risk factors among Chinese older adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014;11:3956–71.

6. Bi UY, Jiang Y, He J, Xu Y, Wang L, Xu M, et al. Status of cardiovascular health in Chinese adults. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:1013–25.

7. Xue H, Wang C, Li Y, Chen J, Yu L, Liu X, et al. Incidence of type 2 diabetes and number of events attributable to abdominal obesity in China: a cohort study. J Diabetes 2015:1–9.DOI: 10.1111/1753-0407.12273. [Epub ahead of print].

8. Li MZ, Su L, Liang BY, Tan JJ, Chen Q, Long JX, et al. Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of diabetes mellitus in mainland China from 1979 to 2012. Int J Endocrinol 2013;1281:64–91.

9. Wang J, Zhang L, Wang F, Liu L, Wang H. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in China: results from a national survey. Am J Hypertens 2014;27:1355–61.

10. WHO. Preventing chronic diseases: a vital investment. Geneva:World Health Organization; 2005.

11. Chen S, Conwell Y, Vanorden K, Lu N, Fang Y, Ma Y, et al.Prevalence and natural course of late-life depression in China primary care: a population based study from an urban community. J Affect Disord 2012;141:86–93.

12. Barnes A, Unruh L, Chukmaitov A, Ginneken E. Accountable care organizations in the USA: types, developments and challenges (in press). Health Policy 2014. Available from: http:dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.07.019.

13. Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care,health, and cost. Health Affairs 2008;27:759–69.

14. American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), American College of Physicians (ACP), American Osteopathic Association (AOA).).Joint principles of the patient-centered medical home. 2007.[accessed 3 May] Available from: www.aafp.org/pcmh/principles.pdf.

15. Patient-centered Primary Care Collaborative: The Patientcentered Medical Home's Impact on Cost and Quality: Annual Review of Evidence 2013-2014. Milbank Memorial Fund, 2015.

16. Wang Q, Chawla R, Colombo C, Snyder R, Nigam S. Patientcentered medical home impact on health plan members with diabetes. J Public Health Manag Pract 2014;20:e12–20.

17. van Hasselt M, McCall N, Keyes V, Wensky S, Smith K. Total cost of care lower among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries receiving care from patient-centered medical homes. Health Services Res 2015;50:253–72.

18. Higgins S, Chawla R, Colombo C, Snyder R, Nigam S. Medical homes and cost and utilization among high-risk patients. Am J Manag Care 2014;20:e61–71.

19. Melek S, Norris D, Paulus J. Economic impact of integrated medical-behavioral healthcare: implications for psychiatry. 2014.Milliman American Psychiatric Association Report.

20. Huang Y, Wei X, Wu T, Chen R, Guo A. Collaborative care for patients with depression and diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatr 2013;13:260.

21. Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, Ciechanowski P, Ludman EJ,Young B, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. New Engl J Med 2010;363:2611–20.

22. Lin EH, Von Korff M, Ciechanowski P, Peterson D, Ludman EJ, Rutter CM, et al. Treatment adjustment and medication adherence for complex patients with diabetes, heart disease,and depression: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med 2012;10:6–14.

23. Woltmann E, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron B, Georges H,Kilbourne AM, Bauer MS. Comparative effectiveness of collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions across primary, specialty, and behavioral health care settings:systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatr 2012;169:8.

24. Saneei P, Salehi-Abargouei A, Esmaillzadeh A, Azadbakht L.Influence of dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH)diet on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis on randomized controlled trials. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2014(Jun 27. pii: S0939-4753(14)00205-1. DOI: 10.1016/j.numecd.2014.06.008) [Epub ahead of print].

25. The Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. The 10-year cost-effectiveness of lifestyle intervention or metformin for diabetes prevention An intent-to-treat analysis of the DPP/DPPOS.Diabetes Care 2012;35:723–30.

26. Qiao Q, Pang Z, Gao W, Wang S, Dong Y, Zhang L, et al. A largescale diabetes prevention program in real-life settings in Qingdao of China (2006-2012). Prim Care Diabetes 2010;4:99–103.

27. Qingqing L, Steven S, Lim EL, Taylor R. Population response to information on reversibility of type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med 2013;30:e135–8.

28. Kathol R, deGruy F, Rollman F. Value-based financially sustainable behavioral health components in patient-centered medical homes. Ann Fam Med 2014;172–5.

29. L & M Policy Research, LLC. Evaluation of CMMI accountable care organization initiatives: effect of pioneer ACOs on Medicare spending in the first year. (Evaluation No. Contract HHSM-500-0009i/HHSM-500-T0002). Washington DC: 2013.

30. CMS Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services. Clinical Quality Measures: 2015; 2014. Available from: www.cms.gov/Regulationsand-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/2014_Clinical-QualityMeasures.html.

Ronald O'Donnell Arizona State University –College of Health Solutions,500 N. 3rd St., Phoenix, Arizona 85004, USA

E-mail: ronald.odonnell@asu.edu

15 March 2015;

Accepted 27 March 2015

杂志排行

Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- Effectiveness of an employment-based smoking cessation assistance program in China

- Team-based stepped care in integrated delivery settings

- "Three essential elements" of the primary health care system:A comparison between California in the US and Guangdong in China

- Menopause and the risk of metabolic syndrome among middle-aged Chinese women

- Availability and social determinants of community health management service for patients with chronic diseases:An empirical analysis on elderly hypertensive and diabetic patients in an eastern metropolis of China

- Evaluating the process of mental health and primary care integration:The Vermont Integration Profile