Cardiac Sarcoidosis: Sorting Fact from Fiction in This Rare Cardiomyopathy

2015-05-22IndraneeRajapreyarMDandElizabethLangloisMSNAPRN

Indranee Rajapreyar, MD and Elizabeth Langlois, MSN, APRN

1Center for Advanced Heart Failure, UTHealth Medical School, Houston, TX, USA

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a rare, multisystem disease where granulomas form in various tissues and organs as a result of an immune reaction to an unknown environmental antigen leading to formation of noncaseating epithelial granulomas often in the context of immune dysfunction [1]. From a historical perspective, the initial reports of sarcoid were cutaneous lesions first described by a French dermatologist, Besnier, who identif i ed patients with multiple nodules felt to be related to a lupus-type disease [2]. In the late 1800s two dermatologists,Jonathan Hutchinson (England) and Caesar Boeck(Norway), independently identif i ed sarcoid lesions of the skin. The disease was originally called either Hutchinson’s disease or Boeck’s disease; however,Boeck later used the termsarcoidbecause of the histologic resemblance to sarcoma [3]. The first published report of cardiac sarcoidosis was noted in 1929 by Bernstein, who found granulomas in the epicardium of a patient with systemic sarcoidosis[3]. Autopsy studies from the 1960s onward tried to determine the incidence of symptomatic cardiac involvement; however, there are wide variations in epidemiologic statistics noted in the literature.Although systemic sarcoidosis typically occurs in the lungs, myocardial sarcoidosis signifi cantly impacts prognosis as the symptoms can be either clinically benign or life-threatening arrhythmias leading to sudden cardiac death [4]. The varied cardiac manifestations are a result of the inf l ammation and fi brosis associated with granuloma formation and can include left ventricular dilatation and systolic dysfunction, as well as benign or lifethreatening arrhythmias.

Epidemiology

The incidence and prevalence of systemic sarcoidosis varies widely depending on multiple factors, including race, sex, and geographic location, with Japan and northern European countries having the highest reported annual incidence [5].Systemic sarcoidosis can occur in all age groups;however, it usually manifests itself before the age of 50 years, with three to four times higher incidence in African Americans than in Caucasians,and a higher annual incidence in women than in men in studies done in the United States [3, 5, 6].For cardiac sarcoidosis it is even more challenging to establish the actual incidence and prevalence rates, as there are no standardized diagnostic criteria agreed upon by experts. The presence of subclinical disease is often seen only on autopsy,and emerging cases of isolated cardiac sarcoidosis are now being identif i ed. Cardiac sarcoidosis is often overlooked because endomyocardial biopsy,the gold standard for diagnosis, has a sensitivity of less than 25% owing to the “patchy” nature of the granulomas and sampling errors [7]. Older observational studies suggest that cardiac sarcoidosis is present in 2%–7% of patients with systemic sarcoidosis; however, necropsy studies have shown evidence of cardiac involvement in anywhere from 50% to 70% of sarcoidosis patients [1, 5, 8].Although systemic sarcoidosis has a relatively low mortality rate, cardiac sarcoidosis with the resulting inf i ltrative cardiomyopathy causing progressive heart failure and risk of sudden cardiac death has a mortality rate of 50%–85% in autopsy studies [2, 3, 9].

Clinical Manifestations

Patients with cardiac sarcoidosis are often asymptomatic, with cardiac involvement identif i ed only at autopsy. Symptomatic patients present with various degrees of heart failure, palpitations, and presyncope or syncope due to a wide range of conduction abnormalities directly related to myocardial inf i ltration by granulomas [3, 5]. Ventricular arrhythmias are particularly noted in patients with signif i cant left ventricular dysfunction due to inf l ammation and myocardial fi brosis that can lead to sudden cardiac death [5]. Complete heart block is evident in up to 30% of patients with clinically evident cardiac sarcoidosis and is characteristic of cardiac involvement in patients with known systemic sarcoidosis [3, 5]. Sudden cardiac death remains the second-leading cause of death in these patients, second only to respiratory complications,as the inf l ammation and subsequent scar formation in the right and left ventricles leads to the development of ventricular arrhythmias [5]. Supraventricular arrhythmias, including atrial tachycardia, atrial fi brillation, and atrial fl utter, do occur but are much less common [3].

Early in the disease course, myocardial inf l ammation with tissue edema can lead to diastolic abnormalities. Contractility is usually preserved in the early stages, with only subtle changes in wall thickness identif i ed on echocardiogram. Congestive heart failure usually occurs as a result of widespread inf i ltration of the myocardium, with resulting fi brosis and formation of scar [8]. Right ventricular failure can occur secondary to high pulmonary pressures related to systemic disease and lung involvement. Systolic and diastolic abnormalities, along with chamber dilatation, wall thinning, pericardial effusion, mitral insuff i ciency due to papillary muscle dysfunction, and development of ventricular aneurysms, leads to worsening congestive heart failure. The decline in functional capacity, variable response to treatment, and poor survival are related to the degree of granuloma inf i ltration with resulting decline in left ventricular performance [1, 3, 8, 10]. Progressive heart failure accounts for 25% of the deaths due to cardiac sarcoidosis [10].

Pathophysiology

The underlying abnormality in sarcoidosis is a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to an unknown environmental antigen with resulting formation and tissue inf i ltration by noncaseating granulomas. Major histocompatibility complex II presents the processed antigen to CD4+T lymphocytes and with produces of a variety of cytokines(including TNF-α and interleukins 12, 15, and 18)responsible for the initiation and maintenance of the granuloma [1, 6, 8]. Granulomas consist of a highly differentiated and compact core of mononuclear phagocytes and epithelioid cells surrounded by lymphocytes [6]. With chronic cytokine stimulation, the macrophages can fuse to form a giant multinucleated cell. Granulomas can also resolve,but if they persist and progress, mature granulomas undergo progressive fi brosis, and extensive scarring can occur [6, 8].

Multiple studies have identif i ed genetic factors affecting the development of sarcoidosis as well as the progression of the disease, although there is a high degree of variability with regard to phenotypic expression. HLA genes play a signif i cant role in immune response once an individual is exposed to an environmental antigen. The A Case Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis (ACCESS)identif i ed specific HLA genes (HLA-DRB*1101,HLA-DRB*1201, HLA-DRB*1501, and HLADRB*0402) that had the most signif i cant association for risk of disease [8, 11]. Two TNF-α polymorphisms (rs1799724, rs1800629) are associated with an increased risk of cardiac sarcoidosis [8].Certain genes have also been identif i ed that are associated with a decreased risk of developing cardiac sarcoidosis [12]. The interaction between genes and environmental factors is not well understood and is still under investigation. Epigenetic alterations likely play a role as a mediator for altering gene expression in response to environmental stimuli leading to immune imbalance [13].

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis has been clinically challenging because of the limited sensitivity and specificity of the diagnostic tests available and the low yield of endomyocardial biopsy. Serum ACE levels are elevated in 60% of patients with systemic sarcoidosis, but a normal ACE level does not exclude sarcoidosis.

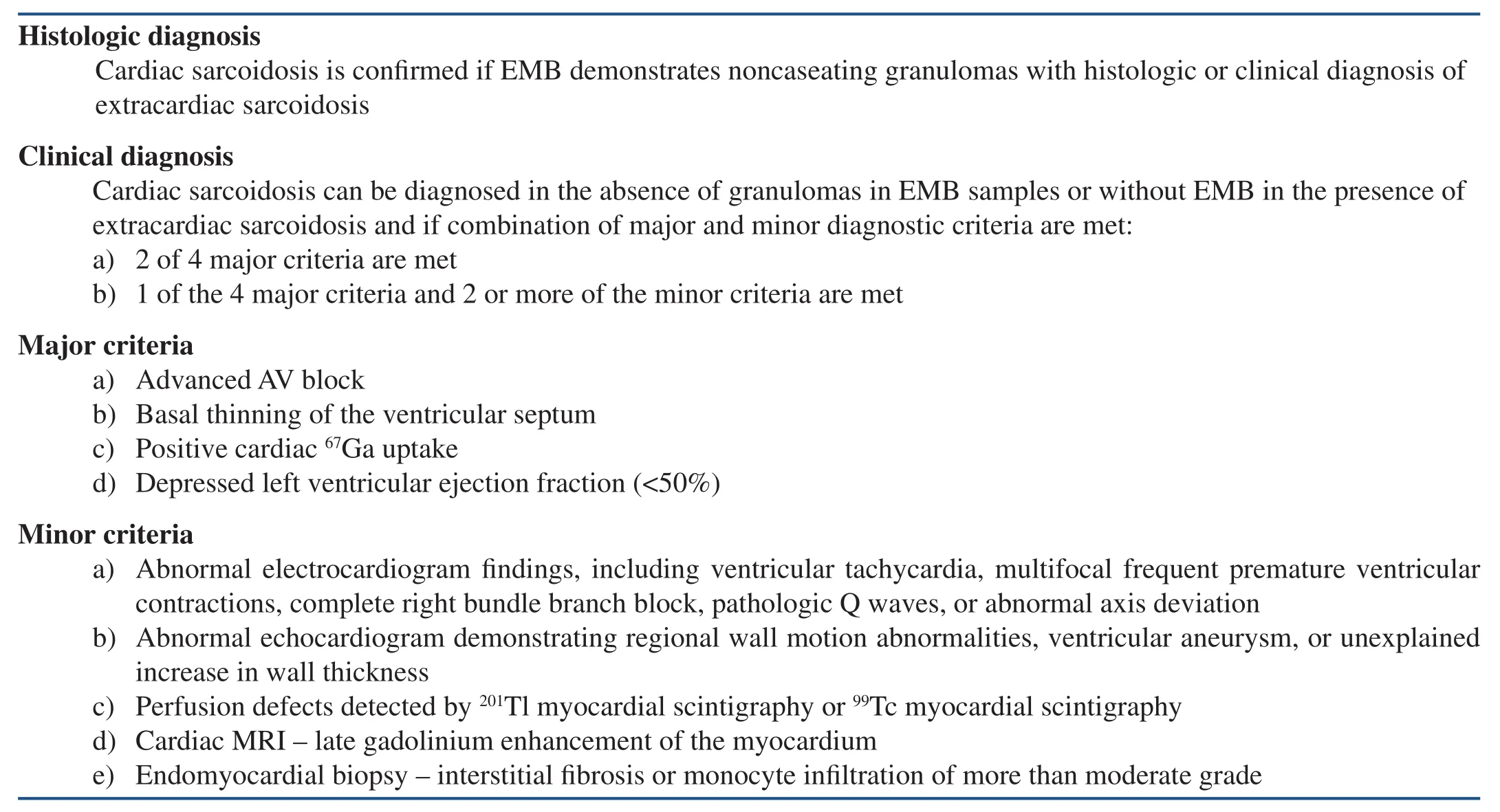

There are currently two diagnostic criteria for diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. In 1993 the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare published the first diagnostic criteria for cardiac sarcoidosis and revised them in 2006 (Table 1) [14, 15]. The revised criteria do not require positive histologic fi ndings for diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. The World Association for Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) sarcoidosis organ assessment instrument requires histologic diagnosis and clinical manifestations [16].

Patients with extracardiac manifestations of sarcoidosis should be screened for the presence of cardiac sarcoidosis. Echocardiogram as a screening tool has limited sensitivity, and only 50% of patients have electrocardiographic abnormalities [9]. Electrocardiographic abnormalities that predict cardiac events in patients with extracardiac sarcoidosis include right bundle branch block, first-degree atrioventricular block, left anterior hemiblock, and fragmented QRS complexes [17]. Echocardiogram as a screening tool has limited sensitivity in detecting patients with disease at early stages but can be used to assess treatment response.

Endomyocardial Biopsy

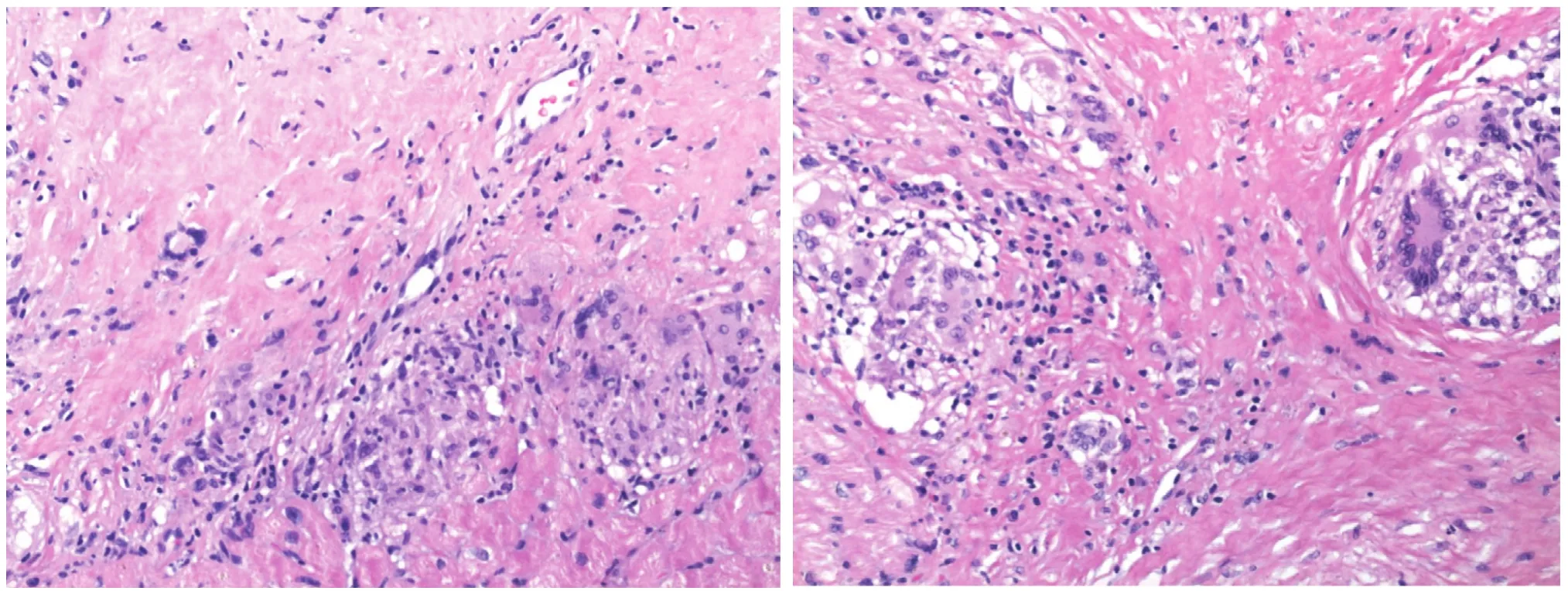

Owing to the patchy distribution of sarcoid granulomas, discordance between conduction abnormalities, the severity of left ventricular dysfunction, and pathologic abnormalities, endomyocardial biopsy has low yield. In an endomyocardial biopsy study involving 26 Japanese patients with sarcoidosis,histologic diagnosis was made in only 19% of the patients. Only one of 15 patients with conduction disturbances and a normal ejection fraction had evidence of noncaseating granulomas in the endomyocardial biopsy specimens. When the disease is advanced, the diagnostic yield is low owing to replacement of granulomas by fi brosis (Figure 1).

Table 1 Revised 2006 Guidelines for Diagnosis of Cardiac Sarcoidosis.

Imaging

Cardiac MRI

Figure 1 Endomyocardial Biopsy Specimen Showing a Noncaseating Granuloma with a Multinucleate Giant Cell of a 63-year-old African American Woman with Systemic Sarcoidosis, Presenting with Third-degree Heart Block.

Cardiac MRI can aid in the diagnosis of sarcoidosis when the distribution of delayed enhancement does not follow the coronary artery distribution.The presence of late gadolinium enhancement(LGE) on cardiac MRI predicts increased risk of death, implantable cardioverter-def i brillator (ICD)discharge, or aborted sudden cardiac death [18].The sensitivity and specificity of cardiac MRI in the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis are 100% and 78%, respectively [19]. The combination of clinical data, echocardiogram, and cardiac MRI improves the specificity [20]. Delayed enhancement is mostly subepicardial in location and explains the low yield of endomyocardial biopsies. Patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 35% have signifi cantly more total affected segments, transmural involvement, and elevated end-diastolic volumes and end-systolic volumes [21]. Cardiac MRI in cardiac sarcoidosis patients has also been used to assess treatment response and prognosis. In a study involving 43 patients with cardiac sarcoidosis, the percentage of LGE mass predicted adverse outcomes. LGE mass greater than 20% was associated with increased cardiac mortality, heart failure hospitalizations, and poor response to steroid therapy [22].

[18F]Fluorodeoxyglucose PET Scan

[18F]Fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) PET in cardiac sarcoidosis has been primarily used to assess disease activity and response to therapy. The role of18F-FDG PET in the initial diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis has several limitations because the techniques used to shift myocardial energy substrate utilization from glucose to free fatty acids may not be reliable. Depending on the studies, the sensitivity is 89% and the specificity is 78% [23]. The presence of a perfusion defect and abnormal18F-FDG uptake predicted increased risk of ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death [24]. The utility of18F-FDG PET to assess response to steroids can be misleading because elevated blood glucose levels with steroid therapy can yield false negative results.

Management

There is no uniform consensus on the treatment of cardiac sarcoidosis patients. The treatment modalities are directed toward prevention and management of life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias, bradyarrhythmias, and heart failure. The following is a systematic review of the management of arrhythmias and heart failure due to cardiac sarcoidosis

Heart Failure

Corticosteroids are the first line of treatment of left ventricular systolic dysfunction in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. In a retrospective study involving 43 patients with cardiac sarcoidosis diagnosed on the basis of the criteria set out by the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare, patients were treated with prednisone at 60 mg every other day and tapered to 10 mg every other day. Patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction between 30% and 55% derived the maximum benef i t, with improvement in left ventricular systolic function and reverse remodeling.Patients with an ejection fraction of less than 30%were older and did not derive any benef i t from corticosteroid therapy [14]. In another study, 67 of 127 patients with cardiac sarcoidosis were given prednisone. In this study, patients given prednisone at time of diagnosis and with a left ventricular ejection fraction greater than 30% had a decrease in the incidence of heart failure events [15]. It is still worthwhile to treat cardiac sarcoidosis with patients with a preserved ejection fraction. In a study involving 40 patients with cardiac sarcoidosis complicated by atrioventricular block but with a preserved ejection fraction, patients with untreated cardiac sarcoidosis had a decline in the ejection fraction and increased incidence of ventricular arrhythmias compared with the treated group (14.3% vs. 61.5%; P < 0.05). In a Finnish study involving 110 patients with sarcoidosis, patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction with an ejection fraction of less than 35% had a signif i cant increase in the ejection fraction [25].The dose of prednisone did not have an impact on the improvement in the ejection fraction. The duration of steroid dose taper and treatment in cardiac sarcoidosis remains unknown. It is uncertain if recovery of the ejection fraction with steroid treatment is permanent and if eventual withdrawal of the use of steroids can cause relapse of disease. Some authors recommend lifelong treatment with lowdose prednisone on the basis of anecdotal reports of relapse and sudden cardiac death after withdrawal of the use of steroids [26]. Mechanical circulatory support or orthotopic heart transplantation is an option for patients with end-stage heart failure. One-year survival after heart transplantation is comparable to that for a cohort of patients who had a heart transplantation for other indications [27,28]. Rare reports of recurrence of sarcoidosis have been described in the transplanted heart [29, 30].Survival after heart transplantation may be affected by other organ involvement.

Immunosuppressive therapy as a steroid-sparing strategy has not been well studied in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. A small study involving 17 patients compared methotrexate plus low-dose steroid versus steroids alone (5–15 mg/day) but did not show any change in the ejection fraction or decrease in left ventricular end-diastolic diameter during 5 years of follow-up in both groups [31]. Several case reports have reported that inf l iximab use in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis resulted in abatement or resolution of symptoms [32, 33].

Ventricular Arrhythmias

Reentry around the granulomas is the most common mechanism for ventricular arrhythmias [34].Prednisone therapy started at 30 mg/day and tapered to a maintenance dose of 10 mg/day has been effective in decreasing premature ventricular contraction burden and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia in patients with an ejection fraction greater than 35%, with no change in burden in patients with an ejection fraction greater than 35% [35]. Medical therapy, which includes a combination of immunosuppressive therapy and antiarrhythmic treatment, was effective in suppressing ventricular arrhythmias only 50% of the time [36]. Approximately 40% of the patients who underwent radiofrequency ablation had recurrence of ventricular arrhythmias [36]. Catheter ablation eliminated ventricular tachycardia in more than two thirds of patients [37]. Predictors of ventricular tachycardia recurrence include left ventricular systolic dysfunction and absence of gallium-67 myocardial uptake before corticosteroid therapy[38]. Extensive scarring and the presence of multiple reentrant circuits require multiple ablation procedures for elimination of ventricular tachycardia. An ICD is recommended in cardiac sarcoidosis patients with sustained ventricular tachycardia,aborted cardiac arrest, and left ventricular systolic dysfunction with an ejection fraction of less than 35% despite optimal medical therapy and immunosuppressive therapy. Other indications for ICD placement in cardiac sarcoidosis patients include syncope or near-syncope thought to be due to ventricular tachycardia, inducible ventricular arrhythmias (less than 30 s of monomorphic ventricular tachycardia), and an indication for permanent pacemaker implantation. ICD implantation in patients who have an ejection fraction between 36% and 49% without any arrhythmias and the presence of LGE on cardiac MRI remains controversial. Inappropriate ICD shocks occurred in one third of patients [9].

Atrioventricular Block

Atrioventricular block in cardiac sarcoidosis has been associated with major cardiac events (cardiac death, heart transplantation, ventricular fi brillation,or sustained ventricular tachycardia) [25]. Recovery from atrioventricular block with steroid therapy occurs in approximately 50% of treated patients[39, 40]. More than 50% of patients with atrioventricular block with cardiac sarcoidosis had fatal cardiac events, and initiation of steroid therapy did not affect survival [41]. Patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction with an ejection fraction of less than 35% are less likely to recover atrioventricular conduction [40]. Controversy remains whether cardiac sarcoidosis patients with advanced heart block will benef i t from an ICD rather than a pacemaker alone.

Prognosis

The survival probability for patients with cardiac sarcoidosis depends on the initial clinical presentation, echocardiographic fi ndings, and treatment with immunosuppressive drugs. In a Japanese cohort of patients, cardiac sarcoidosis patients treated with corticosteroids had better survival than untreated patients. Overall survival was 85% at 1 year and 60% at 5 years. Five year survival in the steroidtreated patients was 75%, compared with 10% in the untreated patients. Steroid-treated patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction greater than 50%had better survival at 5 years than patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 50%(89% vs. 59%). Pulmonary involvement was associated with improved survival [42]. Five-year survival of cardiac sarcoidosis patients presenting with heart failure was 75%. Patients with isolated cardiac sarcoidosis had worse survival free of transplantation and aborted sudden death compared with patients with cardiac sarcoidosis and extracardiac involvement [25].

Conclusion and Take-Home Message

Cardiac sarcoidosis is an evolving entity with many unanswered questions and clinical challenges regarding diagnosis and management. Identifying patients at risk of developing advanced heart failure is diff i cult given the presence of subclinical disease, lack of expert consensus on diagnostic criteria, and limited sensitivity of the current available imaging modalities and endomyocardial biopsy.Early identif i cation of patients is crucial to prevent irreversible progression of disease in this inf i ltrative cardiomyopathy by initiation of treatment with corticosteroids. Even patients presenting with a low ejection fraction have seen an improvement in left ventricular function with steroid therapy, whereas standard heart failure therapies will not affect the progression of granulomatous disease and resulting fi brosis and scar formation. Patients presenting with unexplained advanced heart block even in the presence of normal systolic function should prompt further investigation to establish the cause. Moreover, isolated cardiac sarcoidosis is very diff i cult to diagnose owing to the low yield of endomyocardial biopsy, even with a high index of suspicion.18F-FDG PET and cardiac MRI should be used in conjunction with clinical data, echocardiogram, and electrocardiographic data for diagnosis, treatment,and prognostication. There are currently no reliable serum biomarkers or genetic tests for confirmatory diagnosis. Corticosteroids are the only extensively studied immunosuppressive drugs for treatment of cardiac sarcoidosis. On the basis of available data,it is recommended to continue lifelong therapy with low-dose maintenance corticosteroids.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conf l ict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or notfor-profit sectors.

1. Isobe M, Tezuka D. Isolated cardiac sarcoidosis: clinical characteristics, diagnosis and treatment. Int J Cardiol 2015;182:132–40.

2. Shammas RL, Movahed A. Sarcoidosis of the heart. Clin Cardiol 1993;16(6):462–72.

3. Doughan AR, Williams BR. Cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart 2006;92(2):282–8.

4. Pedrotti P, Ammirati E, Bonacina E, Roghi A. Ventricular aneurysms in cardiac sarcoidosis: from physiopathology to surgical treatment through a clinical case presenting with ventricular arrhythmias. Int J Cardiol 2015;186:294–6.

5. Evanchan JP, Crouser ED,Kalbf l eisch SJ. Cardiac sarcoidosis: recent advances in diagnosis and treatment and an argument for the need for a systematic multidisciplinary approach to management.J Innovations in Cardiac Rhythm Management 2013;4:1160–74.

6. Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA,Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med 2007;357(21):2153–65.

7. Wessendorf TE, Bonella F,Costabel U. Diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2015;49(1):54–62.

8. Hamzeh N, Steckman DA, Sauer WH, Judson MA. Pathophysiology and clinical management of cardiac sarcoidosis.Nat Rev Cardiol 2015;12(5):278–88.

9. Birnie DH, Sauer WH, Bogun F,Cooper JM, Culver DA, Duvernoy CS, et al. HRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of arrhythmias associated with cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart Rhythm 2014;11(7):1305–23.

10. Deng JC, Baughman RP, Lynch 3rd JP. Cardiac involvement in sarcoidosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2002;23(6):513–27.

11. Rossman MD, Kreider ME. Lesson learned from ACCESS (A Case Controlled Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis). Proc Am Thorac Soc 2007;4(5):453–6.

12. Grunewald J, Spagnolo P,Wahlström J, Eklund A. Immunogenetics of disease-causing inf l ammation in sarcoidosis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2015;49(1):19–35.

13. Liu Y, Li H, Xiao T, Lu Q. Epigenetics in immune-mediated pulmonary diseases. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2013;45(3):314–30.

14. Hiraga H, Iwai K, Hiroe M.Guidelines for diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis, study report on diffuse pulmonary diseases. In:Tokyo, Japan: The Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare; 1993.pp. 23–4.

15. Soejima K, Yada H. The work-up and management of patients with apparent or subclinical cardiac sarcoidosis: with emphasis on the associated heart rhythm abnormalities. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2009;20(5):578–83.

16. Judson MA, Costabel U, Drent M,Wells A, Maier L, Koth L, et al.The WASOG sarcoidosis organ assessment instrument: an update of a previous clinical tool. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2014;31(1):19–27.

17. Nagao S, Watanabe H, Sobue Y,Kodama M, Tanaka J, Tanabe N,et al. Electrocardiographic abnormalities and risk of developing cardiac events in extracardiac sarcoidosis. Int J Cardiol 2015;189:1–5.

18. Greulich S, Deluigi CC, Gloekler S, Wahl A, Zürn C, Kramer U, et al.CMR imaging predicts death and other adverse events in suspected cardiac sarcoidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;6(4):501–11.

19. Smedema JP, Snoep G, van Kroonenburgh MP, van Geuns RJ,Dassen WR, Gorgels AP, et al.Evaluation of the accuracy of gadolinium-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance in the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis.J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45(10):1683–90.

20. Yoshida A, Ishibashi-Ueda H,Yamada N, Kanzaki H, Hasegawa T, Takahama H, et al. Direct comparison of the diagnostic capability of cardiac magnetic resonance and endomyocardial biopsy in patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2013;15(2):166–75.

21. Watanabe E, Kimura F, Nakajima T, Hiroe M, Kasai Y, Nagata M,et al. Late gadolinium enhancement in cardiac sarcoidosis: characteristic magnetic resonance fi ndings and relationship with left ventricular function.J Thorac Imaging 2013;28(1):60–6.

22. Ise T, Hasegawa T, Morita Y,Yamada N, Funada A, Takahama H, et al. Extensive late gadolinium enhancement on cardiovascular magnetic resonance predicts adverse outcomes and lack of improvement in LV function after steroid therapy in cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart 2014;100(15):1165–72.

23. Youssef G, Leung E, Mylonas I,Nery P, Williams K, Wisenberg G, et al. The use of 18F-FDG PET in the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis: a systematic review and metaanalysis including the Ontario experience. J Nucl Med 2012;53(2):241–8.

24. Blankstein R, Osborne MT,Waller AH, Murthy VL, Dorbala S, Stevenson WG, et al. Reply:18F-FDG imaging in patients with“suspected,” but not “proven,”sarcoidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64(6):631.

25. Kandolin R, Lehtonen J,Airaksinen J, Vihinen P, Miettinen H, Ylitalo K, et al. Cardiac sarcoidosis: epidemiology, characteristics, and outcome over 25 years in a nationwide study. Circulation 2015;131(7):624–32.

26. Bargout R, Kelly RF. Sarcoid heart disease: clinical course and treatment. Int J Cardiol 2004;97(2):173–82.

27. Perkel D, Czer LS, Morrissey RP, Ruzza A, Raf i ei M, Awad M,et al. Heart transplantation for end-stage heart failure due to cardiac sarcoidosis. Transplant Proc 2013;45(6):2384–6.

28. Zaidi AR, Zaidi A, Vaitkus PT.Outcome of heart transplantation in patients with sarcoid cardiomyopathy. J Heart Lung Transplant 2007;26(7):714–7.

29. Akashi H, Kato TS, Takayama H,Naka Y, Farr M, Mancini D, et al.Outcome of patients with cardiac sarcoidosis undergoing cardiac transplantation–single-center retrospective analysis. J Cardiol 2012;60(5):407–10.

30. Yager JE, Hernandez AF,Steenbergen C, Persing B, Russell SD, Milano C, et al. Recurrence of cardiac sarcoidosis in a heart transplant recipient. J Heart Lung Transplant 2005;24(11):1988–90.

31. Nagai T, Nagano N, Sugano Y,Asaumi Y, Aiba T, Kanzaki H, et al.Effect of corticosteroid therapy on long-term clinical outcome and left ventricular function in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. Circ J 2015;79(7):1593–600.

32. Barnabe C, McMeekin J, Howarth A, Martin L. Successful treatment of cardiac sarcoidosis with inf l iximab. J Rheumatol 2008;35(8):1686–7.

33. Uthman I, Touma Z, Khoury M.Cardiac sarcoidosis responding to monotherapy with infliximab.Clin Rheumatol 2007;26(11):2001–3.

34. Furushima H, Chinushi M, Sugiura H, Kasai H, Washizuka T,Aizawa Y. Ventricular tachyarrhythmia associated with cardiac sarcoidosis: its mechanisms and outcome. Clin Cardiol 2004;27(4):217–22.

35. Yodogawa K, Seino Y, Ohara T,Takayama H, Katoh T, Mizuno K. Effect of corticosteroid therapy on ventricular arrhythmias in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis.Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2011;16(2):140–7.

36. Jef i c D, Joel B, Good E, Morady F, Rosman H, Knight B, et al. Role of radiofrequency catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia in cardiac sarcoidosis: report from a multicenter registry. Heart Rhythm 2009;6(2):189–95.

37. Kumar S, Barbhaiya C, Nagashima K, Choi EK, Epstein LM, John RM, et al. Ventricular tachycardia in cardiac sarcoidosis: characterization of ventricular substrate and outcomes of catheter ablation.Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2015;8(1):87–93.

38. Naruse Y, Sekiguchi Y, Nogami A,Okada H, Yamauchi Y, Machino T, et al. Systematic treatment approach to ventricular tachycardia in cardiac sarcoidosis.Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2014;7(3):407–13.

39. Kato Y, Morimoto S, Uemura A,Hiramitsu S, Ito T, Hishida H.Eff i cacy of corticosteroids in sar-coidosis presenting with atrioventricular block. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2003;20(2):133–7.

40. Yodogawa K, Seino Y, Shiomura R, Takahashi K, Tsuboi I, Uetake S,et al. Recovery of atrioventricular block following steroid therapy in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. J Cardiol 2013;62(5):320–5.

41. Takaya Y, Kusano KF, Nakamura K, Ito H. Outcomes in patients with high-degree atrioventricular block as the initial manifestation of cardiac sarcoidosis. Am J Cardiol 2015;115(4):505–9.

42. Yazaki Y, Isobe M, Hiroe M,Morimoto S, Hiramitsu S,Nakano T, et al. Prognostic determinants of long-term survival in Japanese patients with cardiac sarcoidosis treated with prednisone. Am J Cardiol 2001;88(9):1006–10.

杂志排行

Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications的其它文章

- Strategies to Reduce Heart Failure Hospitalizations and Readmissions:How Low Can We Go?

- Congestive Heart Failure Clinics: How to Make Them Work in a Community-Based Hospital System

- Unusual Cardiomyopathies: Some May Be More Usual Than Previously Thought and Simply Underdiagnosed

- Epidemiological Study of Heart Failure in China

- Noninvasive Hemodynamic Monitoring for Heart Failure: A New Era of Heart Failure Management

- The Evaluation of the Heart Failure Patient by Echocardiography: Time to go beyond the Ejection Fraction