强直性脊柱炎后凸畸形个性化矫形对术后生活质量影响的相关分析

2015-04-25齐鹏宋凯张永刚王岩崔赓

齐鹏 宋凯 张永刚 王岩 崔赓

强直性脊柱炎 ( ankylosing spondylitis,AS ) 是一种主要累及中轴骨及关节的慢性炎症疾病,往往从侵犯骶髂关节开始,并向头侧进展,持续的炎症反应会导致脊柱后凸畸形进行性发展,以致后期影响到患者的站立、行走、平视、平卧、呼吸、饮食及外观,从而严重影响了患者的生活质量[1-4]。手术治疗对于产生畸形的 AS 患者是一种有效的治疗手段,1922 年 Lennan[5]首次提出了全椎体切除的脊柱截骨术 ( vertebral column resection,VCR ),他采用后路顶椎 VCR 配合支具治疗严重脊柱侧凸;1945 年 Smith-Petersen 等[6]描述了后路 1~2 个节段的椎板截骨矫正 AS 后凸畸形,并将其命名为 Smith-Petersen截骨术 ( Smith-Petersen osteotomy,SPO );1984 年Ponte 等[7]报告了 Ponte 截骨术,其运用多水平的SPO 截骨矫正胸段严重的 Scheuermann 病后凸畸形;80 年代经椎弓根脊柱截骨术 ( pedicle subtraction osteotomy,PSO )[8]、蛋壳截骨技术 ( transpedicular eggshell osteotomy )[9]同时出现,各种手术方式的出现为患者手术方案的实施提供了多种选择。但是手术方式仅仅是方法学的一种,如何达到最佳的疗效与手术方案的设计是分不开的。

目前,国内外普遍认为,AS 后凸畸形矫形的最终目的在于:( 1 ) 重建矢状面平衡;( 2 ) 矫正颌眉角[10-15]。然而,对于 AS 后凸畸形矢状面平衡的重建目前还存在争论,部分学者沿用 C7距离骶骨后上角的距离作为矢状面平衡的标准,部分学者将骨盆中立位确立为矢状面平衡的参数[10-16]。近年来,Song 等[17]根据几何学及力学的相关分析,确定出人体的重心标志,并以骨盆参数为基础制定了 AS 后凸畸形的个性化矫形方案,并对此方案进行了前瞻性研究。本研究通过对比个性化 PSO 截骨方案与传统PSO 截骨方案对术后患者生活质量影响的相关性分析,对个性化矫形进行评价。

资料与方法

一、纳入与排除标准

1. 纳入标准:( 1 ) 诊断为 AS 后凸畸形并行截骨矫形术者;( 2 ) 双髋活动良好者;( 3 ) 无脊髓神经症状体征者;( 4 ) 影像学资料完善者。

2. 排除标准:( 1 ) 双髋关节活动受限者;( 2 ) 无法自主完成调查问卷者;( 3 ) 随访资料不完整者。

二、一般资料

2007 年 1 月至 2011 年 11 月,共有 40 例无脊髓神经症状体征、双髋活动良好的 AS 后凸畸形患者纳入本研究,采用随机数字表法将 40 例患者分为A、B 两组,A 组男 14 例,女 6 例,平均年龄 ( 33±9.0 ) 岁,根据 Song 等[17]个性化矫形设计手术方案( 图 1,2 ),若患者颈部强直,则截骨角度应≤自然站立位颌眉角+矫形前骨盆倾斜角 ( pelvic tilt,PT )-理论骨盆倾斜角 ( theoretic pelvic tilt,tPT )[18]。B 组男 16 例,女 4 例,平均年龄 ( 35±9.2 ) 岁,根据 Suk 方法[10],参考术前颌眉角、正常脊柱生理曲度及力线特点[19],设定楔形截骨角度。

三、手术方法

A、B 两组均行后路经椎弓根单节段或双节段楔形闭合截骨矫形椎弓根螺钉内固定术,截骨角度 ( 手术前、后截骨部位头端椎体上终板与尾端椎体下终板之间的 Cobb’s 角度之差 ) 为 16°~85°,平均 39°。

四、研究内容

( 1 ) 骨盆入射角 ( pelvic incidence,PI ),骶骨终板中点垂线与髋轴中点夹角;( 2 ) PT,髋轴中点与骶骨上终板中心铅垂线的夹角;( 3 ) 术前及术后6 个月脊柱侧凸研究学会 ( scoliosis research society,SRS ) -22 评分;( 4 ) 术前及术后 6 个月 Oswestry 功能障碍指数 ( oswestry disability index,ODI )。

五、统计学分析

图1 骨盆侧位示意图 ( HA:髋轴中点;SP:骶骨岬;PSCS:骶骨后上角;PI:骨盆入射角;PT:骨盆倾斜角;SS:骶骨倾斜角;PI = PT + SS )Fig.1 Schematic diagram of the lateral projection of the pelvis ( HA:hip axis. SP: sacrum promontory. PSCS: osterior superior corner of S1. PI: pelvic incidence. PT : pelvic tilt. SS: sacral slope. PI=PT+SS )

图2 单节段个性化截骨设计实例 a:测量术前 PI = 36°;b:tPT = 0.37 × PI - 7 =0.37 × 36 - 7 = 6° 通过理论 PT 作直线HA-HP’,将此线作为该患者骨盆中立位线[17-18];c:选择 L2 作为截骨节段,将椎体皮质前缘闭合点标记为 RP,并作为圆心,RP-HP 为半径作圆交骨盆中立位线与 HP’,也就是将肺门位置重置于骨盆中立位线上,则 ∠HP-RP-HP’ = 50° 即为设计截骨角度。d:L2 共取得 40° + 10° = 50° 的截骨角度,矫形后自然站立位实际 PT = 6°,骨盆处于中立位Fig.2 A case about single personalized pedicle subtraction osteotomies a: the preoperative PI was 36°and the kyphosis of the osteotomy site was 10°; b: tPT=0.37×36-7=6°.

采用 SPSS 12.0 软件进行统计学分析,计量资料中正态分布者采用±s表示,非正态分布者以中位数表示。组间均值比较采用单因素方差分析,P<0.01 为差异有统计学意义。The postoperative plumb line was drawn according to the tPT; c: a circle was drawn by taking the anterior column of the second vertebra ( RP ) as the center, and the distance between this point to the hilus pulmonis and radius. The included angle was 50°, thus the exact required osteotomy angle was 50°; d: postoperative lumbar lordosis was 40°, PT was 6°, and the real osteotomy angle was 40°+10°=50°. Good sagittal balance was achieved

表1 A、B 两组术前资料比较 (±s)Tab.1 Comparison of preoperative data between group A and group B (±s)

表1 A、B 两组术前资料比较 (±s)Tab.1 Comparison of preoperative data between group A and group B (±s)

注:PI:骨盆入射角;PT:骨盆倾斜角;ODI:Oswestry 功能障碍指数;SRS:脊柱侧凸研究学会Notice: PI: pelvic incidence; PT: pelvic tilt; ODI: Oswestry disability index; SRS:Scoliosis research society

项目A 组B 组P 值病例数20 20性别 ( 男 / 女 ) 14 / 6 16 / 4 0.4652年龄 ( 岁 ) 33.0± 9.0 35.0± 9.2 0.4913术前 PI ( ° ) 46.0±10.0 45.0± 9.0 0.7414术前 PT ( ° ) 30.0±14.0 38.0±13.0 0.0688 ODI- 行走 2.0± 0.6 2.1± 0.7 0.4603 ODI- 站立 1.9± 0.9 2.6± 0.9 0.0174 ODI- 总分20.0± 6.0 17.5± 5.3 0.1627 SRS- 外观 1.7± 0.5 1.6± 0.5 0.8961 SRS- 心理 2.3± 0.9 2.4± 0.9 0.5590 SRS- 疼痛 2.4± 1.0 2.6± 1.0 0.4384 SRS- 功能 2.6± 0.5 2.5± 0.5 0.6974 SRS- 满意度 1.6± 0.3 1.4± 0.3 0.0443

表2 A、B 两组术后 ODI 比较 (±s)Tab.2 Comparison of postoperative ODI between group A and group B (±s)

表2 A、B 两组术后 ODI 比较 (±s)Tab.2 Comparison of postoperative ODI between group A and group B (±s)

项目 A 组 B 组P 值ODI- 行走 0.40±0.65 0.60±0.75 0.3746 ODI- 站立 0.40±0.60 0.60±0.75 0.3576 ODI- 总分 2.50±4.00 3.25±3.70 0.5395

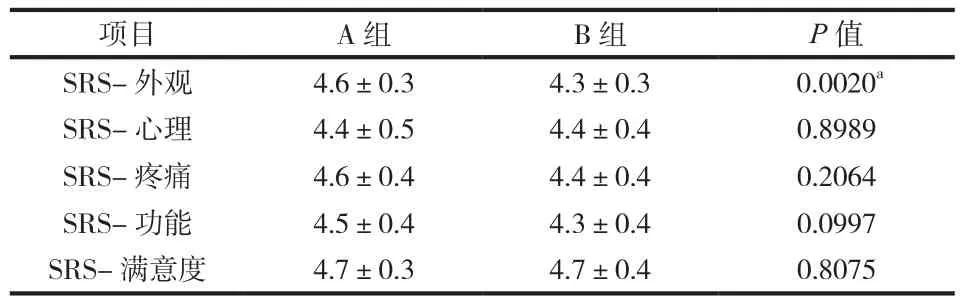

表3 A、B 两组术后 SRS-22 比较 (±s)Tab.3 Comparison of postoperative SRS-22 between group A and group B (±s)

表3 A、B 两组术后 SRS-22 比较 (±s)Tab.3 Comparison of postoperative SRS-22 between group A and group B (±s)

注:aP<0.01,A、B 两组比较,差异有统计学意义Notice: aStatistically significant ifP < 0.01

项目 A 组 B 组P 值SRS- 外观 4.6±0.3 4.3±0.3 0.0020a SRS- 心理 4.4±0.5 4.4±0.4 0.8989 SRS- 疼痛 4.6±0.4 4.4±0.4 0.2064 SRS- 功能 4.5±0.4 4.3±0.4 0.0997 SRS- 满意度 4.7±0.3 4.7±0.4 0.8075

结 果

A、B 两组性别、年龄、术前 PI、PT 值、ODI指数及 SRS-22 评分相比差异无统计学意义 (P>0.01 ),术后 A、B 两组患者外观、心理、疼痛、功能及满意度均趋于正常,且 ODI 指数较术前明显改善 (P<0.01 ),A、B 两组术后 SRS- 外观评分分别为 ( 4.6±0.3 )、( 4.3±0.3 ),差异有统计学意义 (P<0.01 ),SRS- 心理、疼痛、功能、满意度差异无统计学意义 (P>0.01 ),A、B 两组术后 ODI 指数差异无统计学意义 (P>0.01 ) ( 表 1~3 )。

讨 论

AS 患者由于炎症反应,导致局部骨破坏与骨修复反复交替[20],加上炎症累及过程中,后方小关节突关节张力增高导致背部疼痛,人体为减轻小关节压力,出现腰椎保护性前屈,这些可能是形成脊柱后凸畸形的原因。畸形不仅造成了患者外观上的改变,同时,由于躯干重心位置的病理性前移,人体为降低机体能量消耗,达到头-脊柱-骨盆平衡链的稳定,就需要通过代偿矫正矢状面的平衡[21],但是由于脊柱的强直,其代偿能力有限,导致患者通过伸髋、屈膝、后倾骨盆来重置躯干重心位置,长期的伸髋、屈膝带来了持续的肌群紧张进而导致疲劳性疼痛,使得直立活动受限,而且当畸形进一步进展,机体无法代偿时,会严重影响患者的日常生活[22-29]。因此,合理的截骨矫形应当达到患者脊柱序列的改善,躯干重心的后移,且机体不需要后旋骨盆代偿维持直立姿势这一目的,通过 Song 等[17]的研究证实,确保术后骨盆维持中立位 ( PT、SS 恢复至正常区间 ) 比单纯矫正矢状面平衡距离 ( SVA 恢复至正常区间 ) 更有意义,Qian 等[30]通过对 36 例经单节段 PSO 截骨的 AS 患者的术前术后参数测量得出较大 PI 值容易导致矫形不足这一结论,也从一定程度上反映出骨盆参数对于矢状面平衡的重要性。所以,重建人体矢状面平衡,重置全脊柱合理的力线,恢复后旋骨盆至中立位,同时改善平视能力,应为 AS 后凸畸形矫形设计的最重要目标。

本研究中,A、B 两组术后均获得较高的满意度,说明经椎弓根楔形截骨可以很好地提高 AS 后凸畸形患者的生活质量,通过对比 A、B 两组数据,可见 SRS- 外观评分存在着统计学差异,分析两组术后 PI、PT 值,发现两个变量间存在着直线相关性,进一步作回归分析,得出 B 组两变量间存在 PT=0.59 PI - 5.7 直线回归关系,与 A 组相比,B 组 PT均值偏大,说明其平均骨盆后旋恢复程度不够[18],从而导致术后患者骨盆未完全恢复至中立位,髋膝关节仍存在着一部分代偿,且由于 PI 值的个体差异性和骨盆后旋程度的不同,导致了矫形术后颌眉角的不完全可控,虽然这些因素可能对患者心理、疼痛、功能及术后满意度影响相对较小,但是对患者外观的判定存在着一定的影响。同时,代偿性的伸髋、屈膝会导致相应肌群持续性收缩,由此会产生肌群的疲劳性疼痛,最终导致行走、站立困难。一般来说,骨盆代偿性后旋越明显 ( PT 越大 ),其直立活动能力越差[24,29]。虽然两组 ODI 指数差异无统计学意义,但考虑到样本量有限,存在着一定的偏倚,另外从统计数据中可以看出,A 组术后 ODI行走与站立指数均值较 B 组略小,从一定程度上也可以作出相关解释,但是,Sahin 等[31]也指出,AS后凸畸形患者躯干强直会导致其平衡能力较正常人差,行走时必须更加谨慎,所以 AS 患者步行时水平作用力较正常人有所增加,这也使得各关节力矩相应增加,更容易导致肌肉的疲劳,所以具体结论尚须进一步的研究方能得出。

由于条件的限制,本研究也存在着一些不足,如随访资料不够充足,无法比较两组方案的远期效应。同时,样本量比较有限,未能就截骨节段的不同证明其对矫形效果的影响,因此还需要更大的样本量及长期的随访资料进一步的分析研究,但是通过初步的分析对比,可以看出个性化矫形在 AS 后凸畸形手术治疗中的有效性及优越性,特别是对 AS 患者术后生活质量有着较好的改善,同时,对颌眉角的纠正也具有更好的可控性。熟练掌握个性化矫形方法后,可以明显简化手术方案的讨论与争议,并能达到与传统截骨方案相似甚至更好的效果。

[1] Van Royen BJ, De Gast A. Lumbar osteotomy for correction of thoracolumbar kyphotic deformity in ankylosing spondylitis. A structured review of three methods of treatment. Ann Rheum Dis, 1999, 58(7):399-406.

[2] Mac-Thiong JM, Transfeldt EE, Mehbod AA, et al. Can C7 plumbline and gravity line predict health related quality of life in adult scoliosis? Spine, 2009, 34(15):E519-527.

[3] Glassman SD, Bridwell K, Dimar JR, et al. The impact of positive sagittal balance in adult spinal deformity. Spine, 2005,30(18):2024-2029.

[4] Kubiak EN, Moskovich R, Errico TJ, et al. Orthopaedic management of ankylosing spondylitis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg, 2005, 13(4):267-278.

[5] Lennan M. Scoliosis. BMJ, 1922, 2:865-866.

[6] Smith-Petersen MN, Larson CB, Aufranc OE. Osteotomy of the spine for correction of flexion deformity in rheumatoid arthritis.Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1969, 66:6-9.

[7] Ponte A, Vero B, Siccardi GL. Surgical Treatment of Scheuermann’s Hyperkyphosis. Bologna: Aulo Gaggi, 1984: 75-80.

[8] Thomasen E. Vertebral osteotomy for correction of kyphosis in ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1985, (194):142-152.

[9] Heinig CF, Boyd BM. One stage vertebrectomy or eggshell procedure. Orthop Trans, 1985, 9(11):130-136.

[10] Suk KS, Kim KT, Lee SH, et al. Significance of chin-brow vertical angle in correction of kyphotic deformity of ankylosing spondylitis patients. Spine, 2003, 28(17):2001-2005.

[11] Van Royen BJ, De Gast A, Smit TH. Deformity planning for sagittal plane corrective osteotomies of the spine in ankylosing spondylitis. Eur Spine J, 2000, 9(6):492-498.

[12] van Royen BJ, Scheerder FJ, Jansen E, et al. ASKyphoplan: a program for deformity planning in ankylosing spondylitis. Eur Spine J, 2007, 16(9):1445-1449.

[13] Debarge R, Demey G, Roussouly P. Radiological analysis of ankylosing spondylitis patients with severe kyphosis before and after pedicle subtraction osteotomy. Eur Spine J, 2010,19(1):65-70.

[14] Yang BP, Ondra SL. A method for calculating the exact angle required during pedicle subtraction osteotomy for fixed sagittal deformity: comparison with the trigonometric method.Neurosurgery, 2006, 59(4 Suppl 2):ONS458-463.

[15] Aurouer N, Obeid I, Gille O, et al. Computerized preoperative planning for correction of sagittal deformity of the spine. Surg Radiol Anat, 2009, 31(10):781-792.

[16] Le Huec JC, Leijssen P, Duarte M, et al. Thoracolumbar imbalance analysis for osteotomy planification using a new method: FBI technique. Eur Spine J, 2011, 20(Suppl 5):669-680.

[17] Song K, Zheng G, Zhang Y, et al. A new method for calculating the exact angle required for spinal osteotomy. Spine, 2013,38(10):E616-620.

[18] Vialle R, Levassor N, Rillardon L, et al. Radiographic analysis of the sagittal alignment and balance of the spine in asymptomatic subjects. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2005, 87(2):260-267.

[19] Chen IH, Chien JT, Yu TC. Transpedicular wedge osteotomy for correction of thoracolumbar kyphosis in ankylosing spondylitis:experience with 78 patients. Spine, 2001, 26(16):E354-360.

[20] Sieper J, Appel H, Braun J, et al. Critical appraisal of assessment of structural damage in ankylosing spondylitis: implications for treatment outcomes. Arthritis Rheum, 2008, 58(3):649-656.

[21] Duval-Beaupère G, Schmidt C, Cosson P. A Barycentremetric study of the sagittal shape of spine and pelvis: the conditions required for an economic standing position. Ann Biomed Eng,1992, 20(4):451-462.

[22] Jackson RP, McManus AC. Radiographic analysis of sagittal plane alignment and balance in standing volunteers and patients with low back pain matched for age, sex, and size.A prospective controlled clinical study. Spine, 1994, 19(14):1611-1618.

[23] Van Royen BJ, Toussaint HM, Kingma I, et al. Accuracy of the sagittal vertical axis in a standing lateral radiograph as a measurement of balance in spinal deformities. Eur Spine J,1998, 7(5):408-412.

[24] Lafage V, Schwab F, Patel A, et al. Pelvic tilt and truncal inclination: two key radiographic parameters in the setting of adults with spinal deformity. Spine, 2009, 34(17):E599-606.

[25] El Fegoun AB, Schwab F, Gamez L, et al. Center of gravity and radiographic posture analysis: a preliminary review of adult volunteers and adult patients affected by scoliosis. Spine, 2005,30(13):1535-1540.

[26] Jackson RP, Hales C. Congruent spinopelvic alignment on standing lateral radiographs of adult volunteers. Spine, 2000,25(21):2808-2815.

[27] Le Huec JC, Saddiki R, Franke J, et al. Equilibrium of the human body and the gravity line: the basics. Eur Spine J, 2011,20(Suppl 5):558-563.

[28] Legaye J, Duval-Beaupere G. Gravitational forces and sagittal shape of the spine. Clinical estimation of their relations. Int Orthop, 2008, 32(6):809-816.

[29] Chang KW, Leng X, Zhao W, et al. Quality control of reconstructed sagittal balance for sagittal imbalance. Spine, 2011,36(3):E186-197.

[30] Qian BP, Jiang J, Qiu Y, et al. Radiographical predictors for postoperative sagittal imbalance in patients with thoracolumbar kyphosis secondary to ankylosing spondylitis after lumbar pedicle subtraction osteotomy. Spine, 2013, 38(26):E1669-1675.

[31] Sahin N, Ozcan E, Baskent A, et al. Muscular kinetics and fatigue evaluation of knee using by isokinetic dynamometer in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Acta Reumatol Port, 2011,36(3):252-259.