对ADA/EASD以患者为中心高血糖管理路径2015更新的解读

2015-03-02张雪莲

张雪莲

首都医科大学附属北京同仁医院内分泌科

对ADA/EASD以患者为中心高血糖管理路径2015更新的解读

张雪莲

首都医科大学附属北京同仁医院内分泌科

A better Comprehension of “Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes, 2015: A Patient-Centered Approach—Update to a Position Statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes”

张雪莲 北京同仁医院内分泌科副主任医师,博士,临床讲师;主要从事内分泌科疾病的治疗,包括糖尿病、甲状腺疾病等;曾赴香港中文大学生理系进修学习,多次在全国学术年会进行大会发言,参与完成国际多中心大型临床研究;主持国家自然科学基金项目及首都临床特色应用研究,参与完成多项国家自然科学基金项目;在国内核心期刊及国外期刊已发表文章10余篇,并参与校译外文书籍。

近年随着降糖药物种类增多,临床医生在选择与应用降糖药物方面存在不少问题。为此,美国糖尿病协会(ADA)和欧洲糖尿病研究学会(EASD)再次组织召集专家进行讨论,对2012版降糖策略推荐意见[1,2]进行了更新。此次更新2015年2型糖尿病管理指南发表在Diabetes Care杂志上,继续强调对2型糖尿病患者高血糖进行个体化治疗。

血糖控制目标

控制血糖是2型糖尿病管理的重点,但血糖控制当与其他降低心血管风险的方案同时进行,包括戒烟等健康生活方式、控制血压、管理血脂及个体化治疗,如抗血小板治疗等。很多研究证实降低血糖达标值可以减少微血管并发症的发生和进展[3,4],在大血管并发症方面尚无定论,大血管方面获益往往在多年后才能显现[5]。

一系列反映2型糖尿病心血管并发症的大型临床试验结果表明,强化治疗并不是对每位患者都有益处,在老年人群中强化降糖会带来其他风险[6]。故本声明强调血糖控制目标应根据患者的自然病程、病情、伴发疾病、年龄和预期寿命、患者的实际需要、个人意愿及耐受性等因素制订,综合考量降糖的获益与风险,而不是“一刀切”。

为减少糖尿病血管并发症,大多数非妊娠成人2型糖尿病患者合理的糖化血红蛋白(HbA1c)目标为<7%,但应视患者情形进行个体化处理。出现以下情况当严格控糖目标,如低血糖及其他药物不良反应风险较低、病程短、预期寿命长、无严重共患疾病、无血管并发症、治疗态度积极及医疗资源充分等。反之,建议采取较宽松的控糖目标。

以患者为中心的治疗是对患者偏好、需求和价值的尊重和回应,应成为所有慢性病治疗的总原则,这一原则在2型糖尿病治疗过程中尤其需要注意,最终目的是考虑患者的真实生活环境,在经济能力(个人和公共)可承受的范围内,根据自身的生活方式和治疗药物的种类做出最后的治疗决策。

选择适宜的降糖药物

钠-葡萄糖协同转运蛋白2(SGLT2)抑制剂

在药物选择部分,本立场声明中与2012版的最大区别就是引入SGLT2抑制剂[7]。SGLT2抑制剂可使HbA1c降低0.5%~1.0%[8],与多数标准口服降糖药相比,SGLT2抑制剂也有相似降糖作用[9-12],特别是SGLT2降糖作用并不依赖胰岛素,所以,此类药物可应用于2型糖尿病各阶段,甚至当胰岛素分泌功能已严重衰退时。

此外,SGLT2抑制剂还有减重(~2kg,且6~12个月保持稳定)、降压(同时降低收缩压和舒张压,为2~4/1~2mmHg)的优点[7,8,13],在降低血尿酸水平和尿蛋白排泄率方面也表现出积极作用[14]。SGLT2抑制剂可能增加尿路及生殖道感染率[15,16],并且在一些临床试验中观察到其使血肌酐升高(可逆性)[17]、尿钙排泄量增加[18]、低密度脂蛋白轻度升高(~5%,意义尚不明确),故在老年、使用利尿剂、血容量不足的患者中应谨慎使用。由于SGLT2抑制剂的疗效与肾功能状态关系密切,目前认为对于肾小球滤过率<45~60ml/(min·1.73m2)的患者,该药的疗效降低。未来研究还需关注其疗效随时间的变化和对血管并发症的改善作用及其心血管安全性[19]。

噻唑烷二酮类(TZDs)药物

此前研究一直认为TZDs,尤其是吡格列酮与发生膀胱癌有关[20-22],值得高兴的是,近年来许多新证据减轻了此种顾虑。但TZDs易使体重增加和周围性水肿,并伴有增加心衰发生率及骨折风险[23,24]。吡格列酮目前已成为可仿制药物,成本和费用大大降低。

二肽基肽酶-4(DPP-4)抑制剂

肠促胰岛素类药物是目前的研究热点。主要包括两类药物—注射用GLP-l受体激动剂和口服用DPP-4抑制剂。GLP-1受体激动剂可模拟内源性GLP-1的作用,以葡萄糖依赖的方式刺激胰岛素分泌,抑制胰高血糖素生成;DPP-4抑制剂可增加血液循环中活性GLP-l和GIP的浓度,主要作用于胰岛素和胰高血糖素的分泌。

对于DPP-4抑制剂的心血管安全性目前尚无定论,一项大型研究表明DPP-4抑制剂沙格列汀在长期看来对心血管事件并无额外的风险或收益,沙格列汀治疗组患者因心衰而住院的比例更高(3.5%∶2.8%,P=0.007)[25,26]。多项其他研究正在进行中,在研究结果出炉前,在心衰患者中当谨慎使用DPP-4抑制剂。

本声明首次明确了这两种药物的胰腺安全性(包括胰腺炎和胰腺肿瘤的风险)。目前处方提醒有胰腺炎病史者应慎用,但最近更多的大型临床试验表明用药后胰腺疾病的发生率并无显著变化[27]。

给药策略

初始药物治疗

单药治疗中,二甲双胍仍是首选理想药物。目前指南遵循的切点是:男性血清肌酐≥133μmol/ L(≥1.5mg/d1)、女性血清肌酐≥124μmol/L(≥1.4mg/d1)禁用二甲双胍[28]。越来越多的研究表明目前美国的肾脏安全线临界值过于严格,有专家呼吁放宽这一限制,允许轻中度且病情稳定的慢性肾病患者采用二甲双胍治疗[29-31]。有标准提出禁用二甲双胍的切点应为估算肾小球滤过率(eGFR)<30ml/(min·1.73m2),在eGFR<45~60ml/(min·1.73m2)时使用二甲双胍应减量,并加强随访[29,32,33]。

若患者不能使用二甲双胍,则应考虑一种二线药物,但患者肾功能不全时选择受限,此时考虑低血糖风险,磺脲类药物(特别是格列本脲)常不被使用,DPP-4抑制剂在相应的剂量调整后可能是一种较好的选择[34]。

两药或三药联合治疗

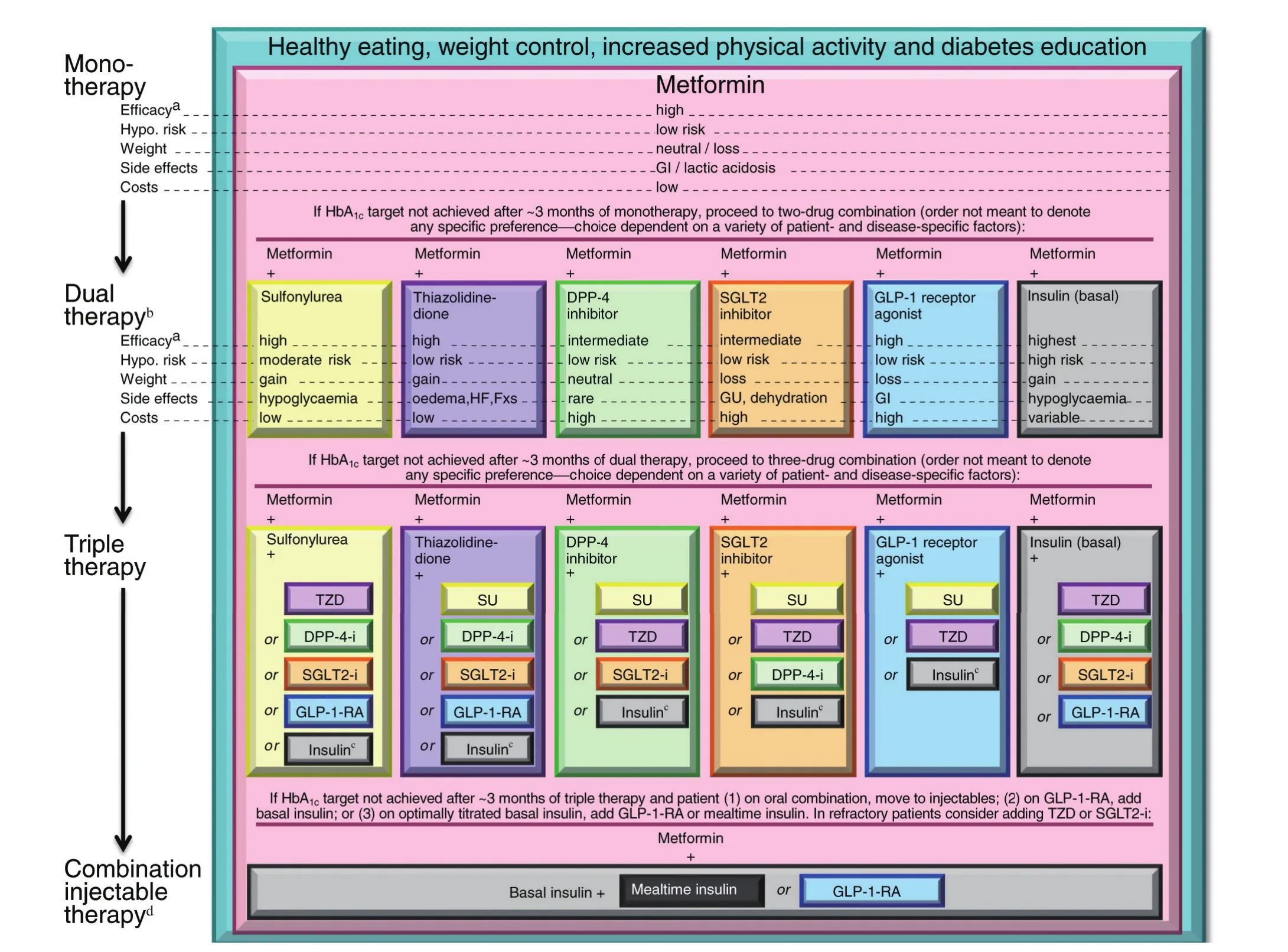

如果单药治疗3个月后HbA1c仍未达标,则需加用另外一种口服药物、GLP-l受体激动剂或基础胰岛素(图1)。

SGLT2抑制剂虽被批准可作单药治疗,但仍主要与二甲双胍或其他降糖药联合使用。研究表明SGLT2抑制剂可作为二线或三线药物的合理选择[35-37]。

与序贯治疗相比,二甲双胍与另一种降糖药联合可使患者更快地达到HbA1c目标。因此,对于基线HbA1c水平远高于控制目标的患者可考虑使用两药联合作为初始治疗,可将HbA1c≥9%作为两药联合治疗的阈值。

联合注射治疗

(1)大多数患者不愿接受注射治疗,但对于病程长、胰岛功能差、联合3种口服降糖药物治疗仍然无法使HbA1c达标的患者,应考虑启动基础胰岛素治疗,并常与二甲双胍联合使用。

(2)在基础胰岛素之外,2012年的声明推荐每日给予1~3次速效胰岛素类似物,或者在某些患者中可以考虑使用预混胰岛素[38]。

(3)近几年研究表明GLP-1受体激动剂与基础胰岛素联用的疗效较餐时胰岛素联用基础胰岛素的疗效相当甚至略优,同时还伴有体重减轻及低血糖发生率减少等获益情况[39-41]。故在上述情况下,基础胰岛素+GLP-1受体激动剂或基础胰岛素+餐时胰岛素是应对这种状况的合理治疗选择,且前者风险更小,并在肥胖和无法操作复杂胰岛素注射的患者中显得更为优越[42-44]。

对GLP-1受体激动剂反应不佳的患者,需采用“基础—餐前”胰岛素方案,即在基础胰岛素基础上于三餐前追加短效或速效胰岛素[45]。与2012版声明相比,本声明明确了各个胰岛素方案的推荐剂量,并在包括餐前短效或速效胰岛素和预混胰岛素在内的各个胰岛素治疗策略方面均有所更新(图2)。

(4)声明同时推荐了两种途径以减少胰岛素用量,提高血糖管理水平。①对于这一阶段的某些患者,加用SGLT2抑制剂或可进一步改善血糖控制、减少胰岛素剂量[46],尤其对肥胖、胰岛素高度抵抗而需要大剂量胰岛素的患者。②联用TZDs类药物,同样可以减少胰岛素用量并降低HbAlc水平[47,48],但其有体重增加、水肿和心力衰竭的不良反应,所以应用时应减量并注意监测。另外,对于胰岛素使用剂量很高的患者也可以选择浓缩胰岛素(常规剂量U-500),可以减少注射量,但需慎用,并向患者和药剂师仔细讲明给药剂量[49]。

对于所有的治疗策略而言,治疗耐受性和药物不良反应均应成为医师考虑的因素。医疗费用也是影响治疗策略的关键因素,不良反应和必要的监测所产生的费用也应考虑在内。复杂的降糖方案仍然无法使血糖很好地达标时,应及时调整控制目标或采取其他手段,如肥胖患者采取代谢性手术等。营养咨询和自我管理教育是贯穿于糖尿病病程各阶段的重要内容,通过有效的咨询和教育确保患者获取相应的降糖方案以及安全监测信息,从而控制血糖水平。同时临床医师应警惕成人隐匿性自身免疫性糖尿病(LADA),患者多通过检测GAD65抗体而确诊[50],临床表现并不典型,其代谢改变类似1型糖尿病,疾病进展远远快于2型糖尿病[51]。虽然短期内口服降糖药物可以控制血糖水平,但最终将发展至胰岛素治疗,最好采用“基础—餐前”方案或胰岛素泵治疗。

药物的选择应基于患者偏好以及不同的患者、病情和药物特点,旨在有效降低血糖的同时最大限度地减少不良反应尤其是低血糖的发生。

其他方面的考虑

与2012版声明相同,本声明继续强调对2型糖尿病患者采取任何治疗措施都要同时考虑影响疾病的其他控制因素,其中年龄是尤为重要的因素,此外还有常见的并发症,如冠心病、心力衰竭、肝/肾功能异常、老年痴呆和高/低血糖风险(以及由此引发的更严重不良反应)等,体重、性别、种族、遗传学差异等也都应纳入决策的考虑范畴。另外,本声明提到一些热点问题也值得关注,如上文所述DPP-4抑制剂与心力衰竭的关系、SGLT2抑制剂与肾功能的关系等。本声明再次重申费用是医疗决策中需要考虑的非常重要的因素,新药往往带来高昂的医疗费用,临床医师可能需要采用更为廉价的仿制药来适应患者的经济能力和个人意愿。

未来的研究方向

本声明最后提及目前正在进行的多项临床试验将在未来1~3年内提供更多关于降糖治疗对心血管疾病影响的数据,这些都将协助医师进一步优化临床决策。另外一项美国大型临床对照试验将于2020年后提供有关二甲双胍单药治疗后多种药物疗效的长期比较数据[52],所以本声明在未来几年仍需进一步更新。

图1 :2型糖尿病抗高血糖治疗建议

2型糖尿病抗高血糖治疗建议∶

(1)对于大多数患者,抗高血糖治疗从改变生活方式开始。

(2)诊断时或诊断之后不久即开始使用二甲双胍单药治疗(有明确的禁忌证除外)。如果患者不耐受二甲双胍,或有禁忌证,可考虑选择“两药治疗”中所示的相应药物进行初始治疗。

(3)如果治疗3个月左右HbA1c未达标,则考虑在二甲双胍的基础上联用以下6种降糖药物之一∶磺酰脲类、噻唑烷二酮类、DPP-4抑制剂、SGLT2抑制剂、GLP-1受体激动剂或基础胰岛素(图中按药物的应用历史和给药途径排序,不代表任何先后次序)。

对于用餐时间不规律或使用磺脲类时出现餐后低血糖的患者,可用速效促泌剂替换磺脲类药物。

其他未列药物(α-葡萄糖苷酶抑制剂、考来维仑、溴隐亭、普兰林肽)可在某些特定情况下尝试使用,但因其疗效有限、给药频繁和/或存在不良反应,一般不作为优先选择。

随着患者的血糖逐渐控制,治疗方案将可以简化∶

(1)在HbAlc>9%的患者中使用两药联合作为起始治疗方案可使血糖更快达标。

(2)启动胰岛素作为初始治疗的切点是血糖水平>16.7~19.4mmol/L或HbAlc>10%~12%,如果高血糖毒性作用缓解,治疗方案可以相应简化。

† ∶这一阶段考虑初始胰岛素治疗的切点为HbA1c>9%;‡∶这一阶段启动初始胰岛素治疗的切点是血糖水平>16.7~19.4mmol/L或HbAlc>10%~12%,尤其对于出现高血糖症状和代谢异常状态(体重下降、任何程度的酮症)的患者,基础胰岛素+餐时胰岛素的起始方案是更佳的选择。基础胰岛素通常为NPH、甘精胰岛素、地特胰岛素、德谷胰岛素等。

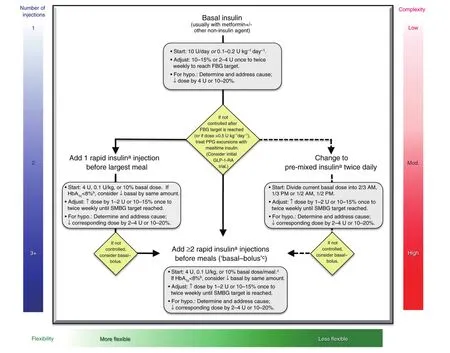

图2 :2型糖尿病胰岛素治疗的起始与调节

2型糖尿病胰岛素治疗的起始与调节∶

(1)单用基础胰岛素是最方便的起始方案,根据高血糖的程度从10U或0.1~0.2U/kg开始。

(2)基础胰岛素通常与包括二甲双胍在内的1~2种非胰岛素类药物联合使用。

(3)接受基础胰岛素治疗时,如果空腹血糖达到理想范围但HbA1c仍未达标,可考虑进一步联用注射剂型以应对餐后血糖的升高。可选方案包括加用一种GLP-1受体激动剂或一种餐时胰岛素(1~3针速效胰岛素类似物,如赖脯胰岛素、天冬胰岛素或赖谷胰岛素)。

此外,还可以考虑从基础胰岛素过渡至每天两次预混胰岛素类似物(70/30天冬胰岛素混合注射液,75/25或50/50赖脯胰岛素混合注射液)。

一些方案比对∶

(1)与速效胰岛素类似物和预混胰岛素类似物相比,常规人胰岛素和人NPH-常规胰岛素预混剂型(70/30)费用较低,但药效学特征决定了其应对餐后高血糖的能力有限。

(2)除了基础+餐时胰岛素注射以外,还可选择一种不常用、费用更高的方案——连续皮下胰岛素注射(胰岛素泵)。

(3)除了基础+餐时胰岛素注射方案外,还有一种方案是∶计算目前每日使用的胰岛素总剂量,然后将该剂量的一半作为基础胰岛素,另一半作为餐时胰岛素并在三餐之间平均分配。

注意事项∶

(1)使用胰岛素治疗时,剂量滴定很重要,应根据血糖水平和各种剂型的药效学特征对餐时和基础胰岛素进行剂量调整。

(2)对于难治性患者,尤其是胰岛素需求量越来越大的患者,使用二甲双胍和一种噻唑烷二酮类药物(通常为吡格列酮)或SGLT2抑制剂有

参考文献

1 Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes:a patient-centered approach. Position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care, 2012,35:1364-1379.

2 Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach. Position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia, 2012,55:1577-1596.

3 Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ, 2000, 321:405-412.

4 UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet, 1998, 352:837-853.

5 Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med, 2008, 359:1577-1589.

6 Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, et al. Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Study Group. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med, 2008, 358:2545-2559.

7 Vasilakou D, Karagiannis T, Athanasiadou E, et al. Sodiumglucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review andmetaanalysis. Ann Intern Med, 2013, 159:262-274.

8 Stenlöf K, Cefalu WT, Kim KA, et al. Efficacy and safety of canagliflozin monotherapy in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus inadequately controlled with diet and exercise. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2013, 15:372-382.

9 Schernthaner G, Gross JL, Rosenstock J, et al. Canagliflozin compared with sitagliptin for patients with type 2 diabetes who do not have adequate glycemic control with metformin plus sulfonylurea: a 52-week randomized trial. Diabetes Care, 2013, 36:2508-2515.

10 Roden M, Weng J, Eilbracht J, et al. EMPAREG MONO trial investigators. Empagliflozin monotherapy with sitagliptin as an active comparator in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2013, 1:208-219.

11 Nauck MA, Del Prato S, Meier JJ, et al. Dapagliflozin versus glipizide as add-on therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes who have inadequate glycemic controlwithmetformin: a randomized, 52-week, double-blind, active-controlled noninferiority trial. Diabetes Care, 2011, 34:2015-2022.

12 Cefalu WT, Leiter LA, Yoon KH, et al. Efficacy and safety of canagliflozin versus glimepiride in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin (CANTATA-SU): 52 week results from a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 noninferiority trial. Lancet , 2013, 382:941-950.

13 Rosenstock J, Seman LJ, Jelaska A, et al. Efficacy and safety of empagliflozin, a sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, as add-on to metformin in type 2 diabetes with mild hyperglycaemia. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2013, 15:1154-1160.

14 Chino Y, Samukawa Y, Sakai S, et al. SGLT2 inhibitor lowers serum uric acid through alteration of uric acid transport activity in renal tubule by increased glycosuria. Biopharm Drug助于改善血糖控制并减少胰岛素用量。

(3)对接受胰岛素治疗的患者中,进行全面的健康教育至关重要,包括血糖自我监测、饮食、锻炼以及避免低血糖并对出现的低血糖做出合理应对。

*∶常规重组人胰岛素和常规中效预混人胰岛素(70/30剂型)是短/速效胰岛素类似物和预混胰岛素类似物的低成本替代品,但往往难以控制餐后血糖波动;†∶胰岛素泵可以很好地代替“基础—餐时”模式的多次注射胰岛素,但由于其费用较高尚未普遍使用;‡∶除图中所述“基础—餐时”模式的起始治疗剂量,另一方法是将当前使用的胰岛素剂量的一半用作基础胰岛素剂量,另一半用作餐时胰岛素剂量,并平均分布于三餐中。Dispos, 2014, 35:391-404.

15 Nyirjesy P, Sobel JD, Fung A, et al. Genital mycotic infections with canagliflozin, a sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor, in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a pooled analysis of clinical studies. Curr Med Res Opin, 2014, 30:1109-1119.

16 Johnsson KM, Ptaszynska A, Schmitz B, Sugg J, Parikh SJ, List JF. Vulvovaginitis and balanitis in patients with diabetes treated with dapagliflozin. J Diabetes Complications, 2013, 27:479-484.

17 Monami M, Nardini C, Mannucci E. Efficacy and safety of sodium glucose co-transport-2 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2014, 16:457-466.

18 Weir MR, Kline I, Xie J, Edwards R, Usiskin K. Effect of canagliflozin on serum electrolytes in patients with type 2 diabetes in relation to estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Curr Med Res Opin, 2014, 30:1759-1768.

19 Neal B, Perkovic V, de Zeeuw D, et al. Rationale, design, and baseline characteristics of the Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study (CANVAS)-a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am Heart J, 2013, 166:217-223.e11

20 Balaji V, Seshiah V, Ashtalakshmi G, Ramanan SG, Janarthinakani M. A retrospective study on finding correlation of pioglitazone and incidences of bladder cancer in the Indian population. Indian J Endocrinol Metab, 2014, 18: 425-427.

21 Kuo HW, Tiao MM, Ho SC, Yang CY. Pioglitazone use and the risk of bladder cancer. Kaohsiung J Med Sci, 2014, 30:94-97.

22 Wei L, MacDonald TM, Mackenzie IS. Pioglitazone and bladder cancer: a propensity score matched cohort study. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 2013, 75:254-259.

23 Dormandy JA, Charbonnel B, Eckland DJ, et al. PROactive investigators. Secondary prevention of macrovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes in the PROactive Study (PROspective pioglitAzone Clinical Trial In macroVascular Events): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 2005, 366:1279-1289.

24 Colhoun HM, Livingstone SJ, Looker HC, et al. Scottish Diabetes Research Network Epidemiology Group. Hospitalised hip fracture risk with rosiglitazone and pioglitazone use compared with other glucose-lowering drugs. Diabetologia, 2012, 55:2929-2937.

25 Scirica BM, Bhatt DL, Braunwald E, et al. SAVORTIMI 53 Steering Committee and Investigators. Saxagliptin and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med, 2013, 369:1317-1326.

26 Scirica BM, Braunwald E, Raz I, et al. SAVORTIMI 53 Steering Committee and Investigators. Heart failure, saxagliptin and diabetes mellitus: observations from the SAVOR - TIMI 53 randomized trial. Circulation, 4 September 2014 [Epub ahead of print]

27 Egan AG, Blind E, Dunder K, et al. Pancreatic safety of incretin-based drugsdFDA and EMA assessment. N Engl J Med, 2014, 370:794-797.

28 Salpeter SR, Greyber E, Pasternak GA, Salpeter EE. Risk of fatal and nonfatal lactic acidosis with metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2010, Apr 14(4):CD002967.

29 Lipska KJ, Bailey CJ, Inzucchi SE. Use of metformin in the setting of mild-to-moderate renal insufficiency. Diabetes Care, 2011, 34:1431-1437.

30 Nye HJ, Herrington WG. Metformin: the safest hypoglycaemic agent in chronic kidney disease? Nephron Clin Pract, 2011, 118:c380-c383.

31 Pilmore HL. Review: metformin: potential benefits and use in chronic kidney disease. Nephrology (Carlton), 2010, 15:412-418.

32 Lu WR, Defilippi J, Braun A. Unleash metformin: reconsideration of the contraindication in patients with renal impairment. Ann Pharmacother, 2013, 47:1488-1497.

33 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Type 2 diabetes: the management of type 2 diabetes [CG87]. London, NICE, 2009.

34 Groop PH, Del Prato S, Taskinen MR, et al. Linagliptin treatment in subjects with type 2 diabetes with and without mild-to-moderate renal impairment. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2014,16:560-568.

35 Phung OJ, Sobieraj DM, Engel SS, Rajpathak SN. Early combination therapy for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2014, 16:410-417.

36 Musso G, Gambino R, Cassader M, Pagano G. A novel approach to control hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: sodium glucose co-transport (SGLT) inhibitors: systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized trials. Ann Med, 2012, 44: 375-393.

37 Goring S, Hawkins N, Wygant G, et al. Dapagliflozin compared with other oral anti-diabetes treatments when added to metformin monotherapy: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2014, 16: 433-442.

38 Holman RR, Thorne KI, Farmer AJ, et al. 4-T Study Group. Addition of biphasic, prandial, or basal insulin to oral therapy in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med, 2007, 357:1716-1730.

39 Eng C, Kramer CK, Zinman B, Retnakaran R. Glucagonlike peptide-1 receptor agonist and basal insulin combination treatment for the management of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet, 11 September 2014 [Epub ahead of print]

40 Diamant M, Nauck MA, Shaginian R, et al. 4B Study Group. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist or bolus insulin with optimized basal insulin in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 2014, 37:2763-2773.

41 Buse JB, Bergenstal RM, Glass LC, et al. Use of twice-daily exenatide in basal insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med, 2011, 154: 103-112.

42 Balena R, Hensley IE, Miller S, Barnett AH. Combination therapy with GLP-1 receptor agonists and basal insulin: a systematic review of the literature. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2013, 15: 485-502.

43 Charbonnel B, Bertolini M, Tinahones FJ, Domingo MP, Davies M. Lixisenatide plus basal insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. J Diabetes Complications, 18 July 2014 [Epub ahead of print]

44 LaneW, Weinrib S, Rappaport J, Hale C. The effect of addition of liraglutide to high-dose intensive insulin therapy: a randomized prospective trial. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2014, 16: 827-832.

45 Davidson MB, Raskin P, Tanenberg RJ, Vlajnic A, Hollander P. A stepwise approach to insulin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and basal insulin treatment failure. Endocr Pract, 2011, 17:395-403.

46 Rosenstock J, Jelaska A, Frappin G, et al. EMPA-REG MDI Trial Investigators. Improved glucose control with weight loss, lower insulin doses, and no increased hypoglycemia with empagliflozin added to titrated multiple daily injections of insulin in obese inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 2014, 37:1815-1823.

47 Charbonnel B, DeFronzo R, Davidson J, et al. PROactive investigators. Pioglitazone use in combination with insulin in the prospective pioglitazone clinical trial in macrovascular events study (PROactive19). J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2010, 95:2163-2171.

48 Shah PK, Mudaliar S, Chang AR, et al. Effects of intensive insulin therapy alone and in combination with pioglitazone on body weight, composition, distribution and liver fat content in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2011, 13:505-510.

49 Davidson MB, Navar MD, Echeverry D, Duran P. U-500 regular insulin: clinical experience and pharmacokinetics in obese, severely insulin-resistant type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care, 2010, 33:281-283.

50 Hawa MI, Buchan AP, Ola T, et al. LADA and CARDS: a prospective study of clinical outcome in established adult-onset autoimmune diabetes. Diabetes Care, 2014, 37:1643-1649.

51 Zampetti S, Campagna G, Tiberti C, et al. High GADA titer increases the risk of insulin requirement in LADA: a 7-years of follow-up (NIRAD Study 7). Eur J Endocrinol, 11 September 2014 [Epub ahead of print]

52 Nathan DM, Buse JB, Kahn SE, et al. GRADE Study Research Group. Rationale and design of the glycemia reduction approaches in diabetes: a comparative effectiveness study (GRADE). Diabetes Care, 2013, 36:2254-2261.

10.3969/j.issn.1672-7851.2015.04.003