泰国性策略

2014-02-20比亚叨达他威邦西邦PiyaladaThaveeprungsriporn

M.L.比亚叨达·他威邦西邦/M.L.Piyalada Thaveeprungsriporn

李若星 译/Translated by LI Ruoxing

泰国性策略

M.L.比亚叨达·他威邦西邦/M.L.Piyalada Thaveeprungsriporn

李若星 译/Translated by LI Ruoxing

建筑长久以来被认为是居住者精神和特性的重要体现。当我们在全球化时代中经历着极端的流动性时,“我们在哪里”以及与之直接相关的“我们是谁”的观念变得越来越模糊。简而言之,建筑作为个人和文化身份表达的观念陷入了从未有过的困境。但是,当我们更细致地观察时,我们开始发现日常生活中的细微差别仍然根植于文化之中。我们体内的“泰国性”仍然在各种方面起作用,许多文化和艺术作品强烈地表现出这种感觉。本文将研究这些揭示出泰国性诗意的多样方式。

文化特性,泰国性,符号化形式,空间体验,当代建筑

文化特性的概念在建筑领域并不新鲜,它在最近40年的建筑文献中经常被研究和讨论。据推测,建筑应具有特性的最早的提倡是针对现代单调城市景观提出的一个后现代批判。诺伯格-舒尔兹的《场所精神:迈向建筑现象学》(1979)和肯尼斯·弗兰姆普顿的《走向批判地域主义:建筑抵抗的六点》(1983)是关注无场所性和非精神性建成环境的时代特性的少有经典著作[1-2]。在新千年里,场所的观念和它的文化特性在建筑文献中仍然具有巨大的价值,这在数不胜数的出版物和论坛中可见1)。在泰国的背景下,文化特性在艺术和建筑中一直是个吸引人的主题,有时甚至是最重要的问题。但是在过去的10年里,当地建筑师越来越多地受到世界各地最新作品的激发,对文化特性的兴趣逐渐衰退。这是否与突然在网络平台上大量传播的建筑设计信息相关,还需要更多的调查,然而明显的是,泰国当代建筑设计的文化特性再一次成为问题。在当今的时代,城市居住者在表面上过着相似的生活、吃着相似的连锁餐厅、依赖相似的国际化品牌、购买相似的居家用品,文化特性是否还对当代建筑设计具有任何意义?是否已经几乎无关——“我们不再生活在旧时代,所以泰国性可以是任何属性”?或者我们抛弃它只是因为我们太过无知而不能深层挖掘泰国特性的传承?但是,在最近几年,为数不多的几个展览重新点燃了艺术领域对泰国性的兴趣——最为相关的是暹罗建筑师协会(ASA)年度展览会Architect' 11上的“解密泰国特性”(Plod Lock Ekaluck Thai, 2011)。另一个在曼谷艺术文化中心的展览“酷泰国”(Thai Tay, 2012)探索了泰国当代社会中艺术和文化更为广泛的领域。巴差·素威拉蓬的《泰国特性:从泰国到泰国的泰国》(Attaluck Thai: Chak Thai Soo Thai Thai , 2011)也证明了宣传和大众媒体对泰国特性兴趣的复兴。

在兴趣重新产生的状况下,本文探索在建筑中表达泰国性诗意的方式。鉴于需要考虑的广阔的时间框架和多样的作品,这固然是极具挑战的一项工作,具有过度简化的风险。因此,本文的第一部分将简要地考察当代建筑实践(1933-1982)对泰国文化特性的多种表达,以提供一种总体的、历史性的综述。第二部分聚焦于将泰国性作为当代泰国建筑设计的灵感之源。

1 泰国性的足迹 | 简要的综述(1933-1982)

像在许多非西方国家一样,现代建筑在泰国并不是一个自然产生的现象,而是“进口的”。第一批受到欧洲训练的泰国建筑师开始他们的现代专业实践,在皇室赞助下于1933年成立了暹罗建筑师协会,并在同年积极投身于建立泰国第一所建筑学校——朱拉隆功大学的建筑学院。在那个时期,现代建筑在欧洲和美国正处于巅峰,现代思想和风格很自然地通过这些建筑师的实践传播,并波及到朱拉隆功的建筑课程设置。因此,一种刺眼的横亘在传统和现代之间的断裂是不可避免的。1933年之后对泰国建筑进化的研究揭示出,现代与传统泰国建筑设计和实践在实质上具有各自独立的方式[3]。

1 帕西玛哈他寺平常大厅,曼谷,1942(建筑师:帕·邦比集尔)/The Ordinary Hall, Wat Phra Srimahathat, Bangkok (1942), by Phra Prompijitr(1-5、7、8图片来源:Pussadee Tiptus)

The topic of cultural identity in architecture is nothing new. It has been frequently examined and debated in architectural discourses over the last 40 years. Presumably, calls for an architecture with a sense of identity originally surfaced as a postmodern critique of the Modern monotonous cityscape. Christian Norberg-Schulz's Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture (1979) and Kenneth Frampton's Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance (1983) are but a few leading works that reflect concern about placelessness and the uninspired built environment of the time[1-2]. And the notion of place and its cultural specificity have remained of great value in architectural discourse well into the new millennium as evident in numerous publications and symposia since that time1). In the Thai context, cultural identity in art and architecture has always been a topic of interest, at times more so than others. Over the last decade, however, such interest seems to have subsided as local architects have become increasingly inspired by the latest works from around the world. Whether that has anything to do with the sudden proliferation of design info through web-based architectural publications requires further investigation. It is nevertheless clear that the relevance of cultural identity in Thai contemporary architectural design is once again being called into question. In a day and age when, ostensibly, urban dwellers lead similar lives, eat at similar chain restaurants, rely on similar global brands and consume similar household products, does cultural identity still mean anything for contemporary architectural design? Does it become virtually irrelevant-"We-don't-live-in-the-old-days-anymore-so-itcan-be-anything Thai-ness"? Or do we dismiss it simply because we are too ignorant to dig deep into what Thai identity entails? In recent years, a few exhibitions have rekindled artistic interest in Thai-ness—the most relevant being Plod Lock Ekaluck Thai (Unlocking Thai Identity) in ASA's annual exposition Architect’11 (2011). Another exhibition, Thai Tay (Cool Thai), at the Bangkok Art and Cultural Center (2012) explored the broader realms of art and culture in contemporary Thai society. Pracha Suweeranon's book Attaluck Thai: Chak Thai Soo Thai Thai (Thai Identity: From Thai to Thai Thai, 2011) is also a testament to a resurgence of the interest in Thai identity in advertising and mass media.

With such a renewed interest in mind, this essay explores the manners in which the poetics ofThainess is manifest in architecture. Given the broad timeframe and variety of works to be considered, this is admittedly an extremely challenging task, running the risk of oversimplification. As such, this review should be considered a mere synopsis of a complex phenomenon. With that in mind, the first part of the essay will briefly examine the various expressions of Thai cultural identity in modern architectural practice (1933-1982), providing an overview or a historical survey of sort. The second part will then focus on Thainess as design inspiration for contemporary Thai architecture.

1 Traces of Thainess | A Brief Survey (1933 -1982)

As in many other non-western countries, Modern architecture in Thailand was hardly an indigenous phenomenon, rather it was something "imported". The first generation of European-trained Thai architects started their modern professional practice and formed the Association of Siamese Architects under Royal Patronage in 1933 and was active in the foundation of the first architecture school in the country, namely the Faculty of Architecture, Chulalongkorn University, in the same year. At such a time, when Modern architecture was at its peak in Europe and the United States, it was only natural that Modern thinking and stylistic influences would spread through these architects' practices and penetrate the architectural curriculum at Chulalongkorn. Given this, a glaring discontinuity between tradition and the modern was inevitable. Studies of the evolution of Thai architecture from 1933 onward reveal the almost entirely segregated paths of modern and traditional Thai architectural designs and practices[3].

Taking a closer look, traces of "Thai-ness"-broadly defined here as a constellation of geographical, climatic, socio-cultural and aesthetic particularities-in architecture emerge. On the one hand, Classical/Traditional Thai architecture practice carried on, continuing its reliance on traditional formal language, spatial order, symbolism and tectonic and decorative details. Modern materials and construction technology were well adopted yet still more or less subservient to traditional forms (fig.1). It is noteworthy that these traditional buildings mostly served traditional functions-i.e. religious and ceremonial structures.

Presence of Thainess in "modern" buildings was relatively diverse. Generally speaking, they may be arranged into 3 categories: (1) Conventional Thai, (2) Tropical Thai and (3) Contemporary Thai. Closest in appearance to Traditional Thai architecture, yet not to be mistaken as one, is Conventional Thai, whose most distinguishing features are dominating pitched roofs, symmetrical building organization and traditional decorative elements. These features were simply applied to the top of a modern structure so as to "appear Thai" in response to the then prime minister Field Marshal P. Pibulsongkram's "Thai National Identity" policies begun in 1938[3]. Essentially, these buildings differed from their traditional counterparts in that their "Thai" characters lay only in the outward appearancesroofs and facades. Their architectonic elements, spatial order, tectonic language and functions were mostly non-traditional-e.g., schools, governmental offices, to name a few. Put simply, they were modern buildings with traditional looking roofs and decorations applied as signification of Thai-ness (fig.2-4).

If the Conventional buildings were Thai by intention, those classified as Tropical Thai would therefore be "just" Thai. The formal language of these works was decidedly modern, yet with characteristic features that were mostly responsive to the geographical and climatic concerns of the area2). Pitched roofs with broad eaves, roofs with extra long overhangs and sun shading devices such as louvers, brise soleil, and masonry screens were featured prominently in these buildings, which belonged mostly to the period between 1958-19723). In contrast to the deliberate symbolism of the Conventional, the Tropical’s sense of identity seemed perhaps more inherent and natural, although the screen designs in certain cases implied traditional Thai motifs (fig.5-8).

2 差甲邦楼,曼谷,1932(建筑师:M.C.伊德希德讪·吉达甲拉)/Chakkrabongs Building, Bangkok , 1932 (by M.C.Iddhidepsan Kridakara)

进一步看,“泰国性”的痕迹(此处大体定义为地理的、气候的、社会文化的和美学的特性)在建筑中显现出来。一方面,经典或传统的泰国建筑实践在继续,持续依靠传统的形式语言、空间秩序、符号、建构和装饰细节。现代材料和建造技术很好地被采用,但仍然或多或少地屈从于传统形式(图1)。值得注意的是,这些传统建筑大多数服务于传统功能,例如宗教和仪式建筑。

“现代”建筑中的泰国性相对多样化。总体上它们可以分为3种类型:(1) 传统泰国;(2)热带泰国;(3)当代泰国。传统泰国类型的形式最像泰国传统建筑,但是不能与传统泰国建筑混为一谈,它们最为突出的特征是具有主导性的坡屋顶、对称的建筑布局和传统的装饰元素。这些特征只是加在一个现代结构上,从而让建筑“看着像泰国的”,以此回应当时的泰国首相銮披汶·颂堪陆军元帅在1938年提出的“泰国国家特性”政策[3]。本质上,这些建筑与它们对应的传统建筑的差别在于它们的“泰国”特性仅仅依赖于外观——屋顶和立面。建筑元素、空间秩序、建构语言和功能基本上都是非传统的,例如学校、政府办公楼。简而言之,它们是以传统样式的屋顶和装饰表达泰国性的现代建筑(图2-4)。

如果说那些被归为传统泰国类型的建筑带有人为的泰国性,那么,被归为热带泰国类型的建筑则是实实在在的泰国建筑。这些建筑的形式语言完全是现代的,但是具有应对当地地理和气候特性的特征2)。其中显著的特征是宽屋檐的坡屋顶、长长的向外悬挑的屋顶和诸如百叶、遮阳板和砖石幕的遮阳设备,这一时期主要是指1958-1972年3)。与传统泰国类型有意为之的符号象征相比,热带泰国类型的特性价值似乎更为内在和自然,尽管一些案例中的幕墙设计暗示有传统的泰国主题(图5-8)。

3 海关总署(设计:泰国公共工程部)/Department of Customs (by Department of Public Works)

据威蒙西提·霍拉扬古拉(Vimolsiddhi Horayangkura)等人,传统泰国类型风格开始于1938年左右,热带泰国类型的建筑大多数出现于1958-1972年。第三种当代泰国类型在1972年之后引入,是对被视为表面符号的传统泰国风格的批判性反应[4]。它最初的目标是抓住本质特性并以现代设计、材料和技术语言对它们进行再阐释。因此,它主张当代泰国设计应具有泰国的精神特性,而不是简单地从传统“抄袭”。在1970年代出现的一些此类作品是公认的非常成功的作品,例如威洛·西素(Wirote Srisuro)设计的沙拉罗伊寺(Wat Salaloy,图9),Plan建筑师事务所的巴恩·巴里乍德(Baan Parichat),它们为今天的泰国建筑师提供了一个强有力的新方向。

2 当代状况

但是应该被当代泰国建筑吸收的“泰国精神”或者是同样难以捉摸的泰国的“本质特征”究竟是什么?对于这样的“精神”,是否只有一个正确答案?或者由于泰国文化自身多样和复杂的本性,它也具有一定的多样性?还需要考虑的是,将这些品质成功而诗意地融入现代设计之中的复杂程度。该如何完成这项任务?通过形式、空间秩序、建筑细节、符号、材料和建构,或其他?这里有无尽的可能性,所以,只有从多样的当代设计中汲取能力,从而理解泰国文化特性的外在表达方式。根据泰国性的实现方式,相关作品可以被分为两种主要类型:(1)符号形式中的泰国性;(2)空间体验中的泰国性。每种类型还包含子类型,将在下文中给出相应解释。

2.1 符号形式中的泰国性

在所有的当代泰国建筑作品中,通过符号形式表达文化特性的作品是最易于识别的。这些作品可以被分为两个子类型——“叙述性”参考和“阐释性”参考。叙述性形式属于更为“直接”比喻过去的建筑,以多种程度的简化为典型特征,它们是各种“标志性”的招牌。其范围包含从在整体设计上参考传统或乡土建筑(将整体建筑或项目设计为“看起来”像老建筑),到在整体项目的一部分引入传统或乡土建筑(创造出新与旧的混合体)。前者的例子如翁加德·萨特拉班度(Ongard Satrabhandu)设计的罗望子乡村酒店和拉查曼哈酒店,马塔尔·汶纳(Mathar Bunnag)设计的清迈四季酒店,阿颂·信设计的阿颂·信艺术研究院。这些作品易于被识别为“乡土的泰国”,但是仔细辨别能够发现其中巧妙的现代细节和空间改良。对于混合传统样貌和现代建筑的后者,此类的典型案例有IDIN建筑师事务所设计的普吉岛入口(见本刊P62-65)。有时,传统的部件和模式在非常时尚的现代设计中被运用为装饰主题元素,著名的作品包含建筑系有限公司设计的普吉岛萨拉度假村和CHAT建筑师事务所设计的南达遗址酒店(见本刊P42-45 )。

4 泰国烟草专卖局主楼,曼谷,1957(建筑师:朴·楚拉社沃)/ Main Building, Thailand Tobacco Monopoly, Bangkok, 1957 (by Bhol Chulasewok)

另一方面,阐释性参考则意味着更少“直接的”、更多“选择性的”或“批判性的”在现代设计中融入传统。它同时包含标志性和符号化的参考4)。不论是项目的尺度还是意义,最为突出的案例是阿颂·信和敦信工作室设计的沙帕亚·沙帕·斯他恩(Sappaya Sapa Sthaan)和新国会大厦,建筑师在概念象征和形式类比中都运用了传统要素。其他的案例包含将一种或者多种传统主题诗意性地阐释在现代设计中,一个很好的例子是马塔尔·汶纳设计的华欣巴莱温泉酒店(The Barai in Hua Hin)。另一个运用单一主题的案例是汶颂·普雷姆塔(Boonserm Premthada)设计的坎塔纳电影动画学院,它只通过技巧性地运用材料产生奇妙的戏剧性效果。

尽管通过形式类比表达文化特性可能太过直接和简单,它却是相对有力的,因而更易于与大众交流(即那些没有艺术和建筑背景的人)。它看起来很简单,但是要想在当代语言中成功地对传统形式进行再创造或再阐释,需要对影响美学和结构形式的传统文脉和多样因素有深度的知识和理解,更不用说比例、秩序和建构细节。实际上,就美感(一种审美趣味)而言是要求非常高的,一点微微的“脱离”比例或曲线就让人们立刻感受到这个作品某些地方不对。

2.2 空间体验中的泰国性

According to Vimolsiddhi et al, ConventionalThai style began sometime after 1938, while works in the Tropical Thai category appeared mostly during 1958-1972. The third category, Contemporary Thai, was only introduced around 1972 onward as a critical reaction to the allegedly superficial symbolism of Conventional Thai style[4]. Its primary goal was to capture essential characteristics and reinterpret them through the language of modern design, materials and technology. Contemporary Thai designs, accordingly, should bear the spirit ofThai-ness without simply "copying" from tradition. There were not a few works in this category from 1970's which were deemed highly successful-Wat Salaloy by Wirote Srisuro (fig.9), Baan Parichat by Plan Architects, etc.-and these set a strong new direction for Thai architects today.

2 The Contemporary Situation

But what exactly is this "spirit of Thai-ness" or are its equally elusive "essential characteristics" that should be incorporated in Contemporary Thai architecture? Is there only one correct answer to such a "spirit" or is it multifarious due to the diverse and complex nature of Thai culture(s) itself? And not to mention the intricacy involved in successfully and poetically reintroducing such qualities in modern design. How does one do it? Through forms, spatial orders, architectonic details, symbolism, materials and tectonic, or what? The possibilities are endless. It seems only reasonable to examine contemporary design to understand how Thai cultural identity might be manifest. Here work can be grouped into two main categories based on the way Thai-ness is achieved: Through symbolic forms or through spatial experience. Each option contains sub-categories that should be explained.

2.1 Thai-ness through Symbolic Forms

In Contemporary Thai projects, ones which express cultural identity through symbolic forms seem the most readily recognizable. These may be classified into two subcategories-those using "descriptive" references and those using "interpretive" ones. Descriptive forms belong to architecture with a relatively more "direct" analogy to those of the past, typically with various degrees of simplification. They are "iconic" signs of sorts.This may range from referencing one's overall design to a traditional or vernacular architecture-by designing the whole building or project to "look like" the old or by introducing traditional or vernacular architecture as a part of whole project-creating a mixture between the old and new. Examples of the former are the Tamarind Village and Rachamankha Hotel by Ongard Satrabhandu, The Four Seasons, Chiang Mai by Mathar Bunnag and the Arsom Silp Institute of the Arts by Arsom Silp. All of these would be readily recognized as "vernacular Thai" but discerning eyes would see the adeptly integrated modern details and spatial modification of the tradition. For a mixture of traditional and modern, is Phuket Gateway by IDIN Architects is a prime example and is featured in this volume. Occasionally, traditional parts or patterns are adopted as thematic decorative elements in sleek modern designs. Noted works in this last group include Sala Phuket by Department of Architecture and Nanda Heritage by CHAT Architects (also featured in this issue of World Architecture).

On the other hand, interpretive reference involves a less “direct” and more "selective" or "critical" integration of tradition in modern design. It may involve both iconic and symbolic kinds of reference4). Most prominent, both in terms of project scale and significance, is Sappaya Sapa Sthaan, or the new Parliament Building project, by Arsom Silp and Tonsilp, in which the architects employ tradition both in terms of conceptual symbolism and formal analogy. In other cases, it involves adopting one or a variety of traditional motifs to be poetically interpreted through modern design. A fine example of this method would be Mathar Bunnag's The Barai in Hua Hin. Another example of appropriating and expanding on a single motif, one that also involves the selection of single materials applied to intriguing and dramatic effect, is the Kantana Film and Animation Institute by Boonserm Premthada.

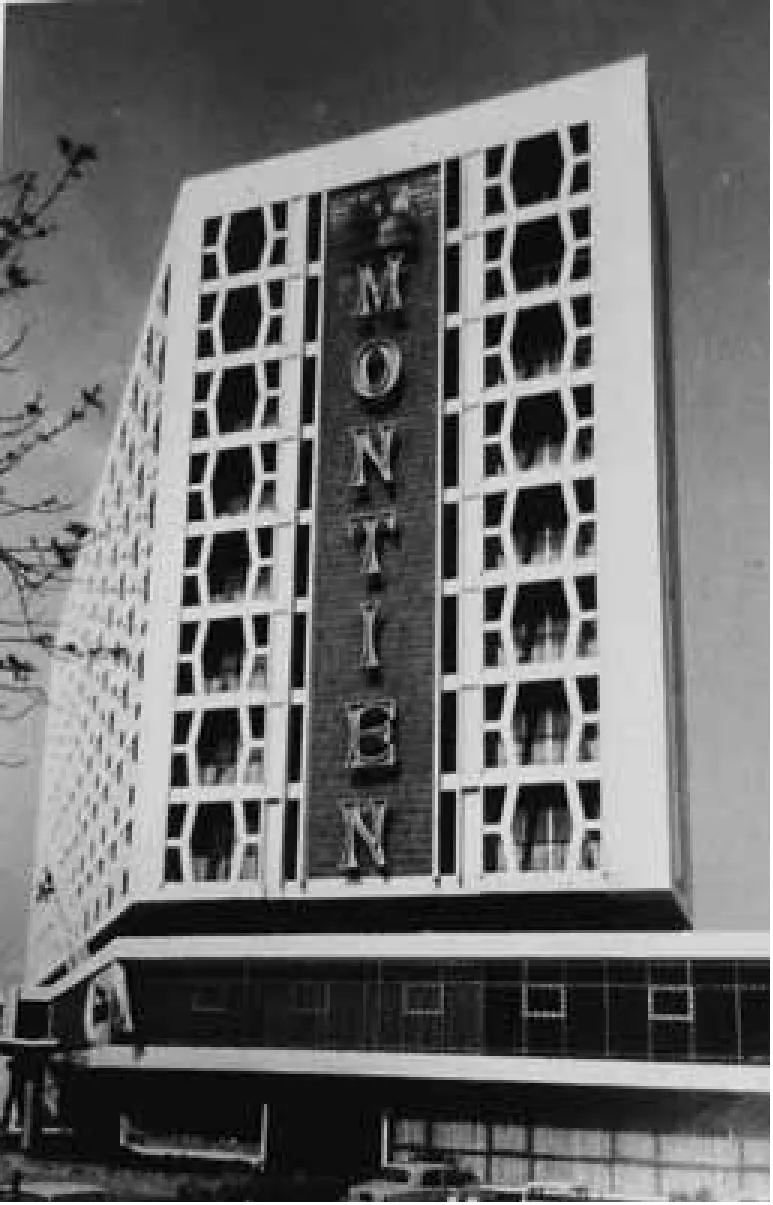

5 芒天酒店,曼谷,1966(建筑师:博·戈·甲森·布沙亚西里)/Montien Hotel, Bangkok, 1966 (by Pol.Col.Kasem Busayasiri)

Although the expression of cultural identity through formal analogy may seem overly direct and simple, it is relatively powerful and hence more readily communicable to the general public-i.e., those with no prior background in art and architecture. Simple as it may seem, to successfully re-create or re-interpret traditional forms in contemporary language requires in-depth knowledge and understanding of the traditional contexts and various factors influencing the aesthetic and architectonic forms, not to mention the proportion, order, and tectonic details. In fact, it is quite demanding in terms of aesthetic sensibility. A slightly "off" proportion or curve and one can immediately sense something is not right about the work.

2.2 Thai-ness through Spatial Experiences

6.7 因陀罗丽晶酒店,曼谷,1970(建筑师:集拉·西尔巴甲诺)/Indra Regent Hotel, Bangkok, 1970 (by Jira Silpakanok)(图片来源:作者自摄)

8 泰国银行,曼谷,1975(楚差瓦·德·韦革尔国际设计部)/ Bank of Thailand, Bangkok, 1975 (by Chuchawal De Weger International)

9 沙拉罗伊寺,呵叻,1977(建筑师:威洛·西素)/Salaloy Temple, Nakon Ratchasima, 1977 (by Wirote Srisuro)

在形式类比之外,泰国性感受在当代设计中也可以通过空间体验表达。这类体验包含作品整体的气氛,或是通过空间边界的特殊编排方式产生的空间品质和特征。此类作品中文化气息的阐释可能更为微妙和开放,它被“感受到”,而不仅仅是被“看到”。这类作品的案例可以粗略地分为两组:应对泰国建筑的“气候”方面和“建构”方面。起初,这类作品可能与任何文化性关联甚微,尤其是应对气候的作品。但是,并不是所有考虑气候的作品都能展现人们视为“东方的”或“泰国的”气氛,这在1960年代的热带泰国类型的作品中已经很常见。但是部分作品具有一些相似的建筑特征,双层表皮是其中最有表现力的一种。这组建筑中的著名作品是阿颂·信设计的因陀般若佛学档案馆(见本刊P32-37)、汶设计的汶勒住宅(Boonlert Residence)和Studiomake工作室设计的帕塔纳画廊(见本刊P70-73),尤其是因陀般若佛学档案馆,不仅在立面上采用了砌体屏幕作为特色,还在建筑首层运用了开放空间,是对传统泰国房子的多功能“tai toon”空间的怀旧。汶勒住宅和帕塔纳画廊的幕墙尽管没有明显地参考传统,其生成的采光特质为室内空间灌注了诗意,与人们在一个泰国房子里的感受差别并不大。另一方面,建筑系有限公司设计的SUNONE办公楼和标准工作室(normalstudio)的I食堂不仅是诗意操纵光影的独特作品,也具有迷人的空间构成,带有些许不易察觉的泰国气息。

建筑建构的诗意在当代建筑思想和实践中非常有名,但是关注泰国建筑建构的作品也许是最为棘手的。其中少有的几个建筑是素里雅·温攀西里拉特(Suriya Umpansirirat)的作品和致力于住所与环境建设的建筑师社团(CASE)设计的十宅。后者是一个非常有趣的项目,它的经济限制剥夺了任何多余的轻浮设计,形成了一种新的“城市乡土”——以最直白而纯粹的形式反应泰国城市生活方式的建筑。同时,素里雅在瓦齐拉班朴寺(乌巴西克住宅)和考布达戈东佛寺(围墙里的精舍,见本刊P54-57)项目中,通过塑造空间边界(如地面、墙和屋顶)的模式达到了极好的效果,产生了具有当地气息的独特“方言”。

如前所述,文化特性或精神的概念是相当复杂的。因此,在许多作品中使用超过一种的“技巧”来形成认同感毫不奇怪。普沙迪(Pussadee)的迪普图斯宅(Tiptus House)、东方建筑师事务所(East Architects)的汶亚瓦·迪普图斯(Bunyawat Tiptus)和比拉斯·帕乍拉沙瓦泰住宅是以传统形式和空间组织作为灵感,并且也是探索热带设计和当代建构的突出案例。

3 结语

建筑长久以来被认为是居住者精神和特性的重要体现。当我们在全球化时代中经历着极端的流动性时,“我们在哪里”以及与之直接相关的“我们是谁”的观念变得越来越模糊。简而言之,建筑作为个人和文化身份表达的观念陷入了从未有过的困境。但是,当我们更细致地观察时,我们开始发现,日常生活中的细微差别仍然根植于文化之中。我们体内的“泰国性”仍然在各种方面起作用,许多文化和艺术作品均强烈地表现出这种感觉。在建筑领域,上文略述的作品远不仅仅是全部。然而,它们帮助呈现出“泰国性”如何在当代建筑实践中表达的一个宏观图景。总体来说,符号形式因为其最为有效仍然扮演着重要角色。因此,在文化特性被“出售”或是被特别重视的项目中——例如度假酒店、政府建筑——经常涉及符号形式。鼓舞人心的是,种类繁多的文化参照都在被运用,它们不仅局限在经典的泰国建筑中,还包含泰国不同地区的乡土形式,因此以充裕的设计资源丰富了当代建筑的景象,并且通过多种程度的分析和阐释获得的成果相当乐观。至于关注于通过热带设计和建构、探讨整体空间体验的作品,其能够达到的“泰国性”可能并不明显,但是这些作品享有一个共同的特征,即建筑师都不遗余力地让自己的作品脱颖而出。毕竟,“泰国性”本身的含义并没有其作为设计灵感的方式更重要。□

注释:

1 )学术组织例如加利福尼亚大学的传统环境研究国际协会(IASTE)、伯克利大学的环境设计学院及其一年两次的论坛和刊物。

2 )这组建筑作品是否能被公认为是“泰国”的或是否拥有设计的文化特性仍然值得商榷。但是,考虑到乡土建筑的本质特征主要存在于地理和气候的感受,热带泰国类型的作品应该被视为固有某一程度的泰国性。然而值得注意的是,这些作品中的建筑元素同样出现在全世界许多热带国家相似时期的现代建筑中,它们也受到当地建筑语汇的启发,例如,砖石幕墙存在于各式各样的土著建筑中,如印加和印度,爱德华·杜雷·斯通对此称赞有加,后来运用到他的许多公共项目中。实际上,爱德华·杜雷·斯通深深迷恋于这种元素,他在自己纽约住宅的立面改造中也使用了它,但纽约并非热带气候。

3 )这段时期非常有趣,因为这些应对气候的设计似乎在1972年之后就沉寂了,可能因为建筑尺寸和复杂度的增大不幸地将建筑师的关注点转移到其他地方。

4 )杰弗里·布罗德本特认为,图像符号是通过物理相似性或共有的特性指向指代物的符号。另一方面,象征符号是通过抽象规则或社会契约的方式指向指代物,可能与外貌毫无关联。参见杰弗里·布罗德本特发表于《建筑设计》(1977年7-8期)的“建筑学符号理论大众指南”一文。

Beside formal analogy, the sense of Thainess in contemporary design may also be expressed through spatial experiences. Such experiences include the overall ambience of the work, its spatial qualities or characteristics, produced by the careful orchestration of the work's spatial boundaries.The cultural flavor in such cases may be subtle and open to interpretation, made to be "felt" not merely "looked at". Examples of works in this category are loosely divided into two : Those responding to the "climatic" and "tectonic" aspects of Thai architecture. At the outset, works in this category may seem to have little to do with anything cultural, particularly the climate-responsive ones. Not all climate conscious work would produce ambiences that one could perceive as "Eastern" or "Thai". Yet ones that do seem to share certain architectonic features, the most expressive of which is the double skin. Notable works in this group are the Buddhadasa Indapanno Archives (BIA, see P32-37 of this issue) by Arsom Silp, the Boonlert Residence by BoonDesign and the Patana Gallery by Studiomake (see P70-73 of this issue). BIA, in particular, not only features masonry screens on its facade, but also makes use of open space at the building's ground level in a way that is reminiscent of the multipurpose "tai toon" space of the traditional Thai house. The screens of the Boonlert Residence and Patana Gallery, although without any overt reference to tradition, generate lighting qualities that imbue the interior spaces with a poetic sensibility not too different from what one may find in a Thai house. On the other hand, SUNONE by Department of Architecture and I-Canteen by normalstudio, despite being unique works with poetic plays of light and shadows as well as captivating spatial configurations, have somewhat less readily perceptible Thai flavor.

The poetics of the making of architecture, the architectural tectonic, has been well celebrated in contemporary architectural thinking and practice. Yet works that focus on the tectonic of Thai architecture are perhaps the trickiest. Few examples can be found. Among the ones that can are works by Suriya Umpansirirath and Ten House by CASE (Community Architects for Shelter and Environment). The latter is quite an interesting example as financial constraints stripped the work of any frivolous excess, resulting in a new "urban vernacular"—an architecture which reflects the urban Thai way of living at its barest, and perhaps purest, form. Meanwhile, Suriya's works at Wat Wachirabanphot (the Ubasika Residence) and Wat Khao Buddhakodom (Walled Monk's Cell, see P54-57 of this issue) play with modes of making spatial boundaries such as the floors, the walls and the roofs to a great effect, resulting in unique "vernaculars" with local flavor.

As mentioned earlier, the notion of cultural identity or spirit is rather complex. It is no surprise, therefore, that in many works, more than one "technique" was used to establish a sense of identity. Tiptus House by Pussadee and the Bunyawat Tiptus and Pirast Patcharasawate's House by East Architects are outstanding examples of projects inspired by traditional form and spatial organization that also explore tropical design and a contemporary tectonic.

3 Epilogue

Architecture has long been recognized as the very embodiment of the identity and spirit of those who dwell in it. As we are buffeted by flow in the age of globalization however, the notion of "who we are" as a direct correlation to "where we are" becomes less and less distinct. In short, the notion of architecture as an expression of self and its cultural identity has never been more in question. Yet, when we look more closely, we begin to realize the nuances and details of our daily lives are still very much culturally situated. The "Thai-ness" in us is still at work in various ways, the very sense that does indeed manifest in many cultural and artistic outputs. The essay will look into the various manners by which this poetic of Thai-ness unveils.

The architecture, the works outlined here, are by no means all inclusive. Nevertheless, they help provide a big picture of how "Thai-ness" is articulated in contemporary architectural practice. In general, symbolic forms still play a significant role as they are most efficient. As such, in projects where cultural identity "sells" or is particularly valued-resort hotels, government buildings, for example-symbolic forms are often involved. What is encouraging is the large variety of cultural references in use. They are not only limited to classical Thai architecture, but inclusive of the vernaculars from different parts of Thailand as well, thus enriching the contemporary architecture scene with the abundance of design resources. With the various degrees of analysis and interpretation at work in these projects, the results look rather promising. As for works that focus on the overall spatial experiences brought about by tropical design and tectonic considerations, the "Thainess" achieved may be less "guaranteed". Yet, such projects provide alternatives that are perhaps more spontaneous and contextual. Either way, what these works seem to share is the architects' passion to make their works stand out from the rest. After all, what "Thai-ness" is may not matter as much as the way it lends itself to design inspiration.□

Note:

1 )Examples include academic organizations such as the International Association for the Study of Traditional Environment (IASTE) of the University of California, Berkeley's College of Environmental Design along with its biannual symposia and journal.

2 )Whether works in this group can be professed as "Thai" or be said to possess a cultural identity by design is still arguable. Yet, considering the fact that vernacular architecture's essential characters mostly lie in its geographical and climatic sensitivity, the Tropical Thai works should be considered inherently Thai to a certain degree. It is noteworthy, however, that the architectonic elements found in these works are shared by modern buildings of the same era in many tropical countries around the world, many of which were also inspired by local vernaculars. Masonry screens, for example, were found in various indigenous architecture-Incan, Indian, for examples-and were later celebrated by Edward Durell Stone in many of his public works. In fact, Stone was so intrigued by the element that he used it on the renovated facade of his own townhouse in the non-tropical New York City.

3 )The period here is quite interesting as these climatic-responsive designs seemed to have subsided after 1972. Perhaps it is the increase in building size and complexity that shifted the architects' concerns elsewhere unfortunately.

4 )Iconic sign, according to Geoffrey Broadbent, is a sign that refers to the object it denotes by physical resemblance or shared characteristics. Symbolic sign, on the other hand, refers to its reference by means of abstract rules or social contracts which may have nothing to do with physical appearance at all. See Geoffrey Broadbent, "A Plain Man's Guide to the Theory of Signs in Architecture," Architectural Design 7-8 (1977).

/References:

[1] Christian Norberg-Schulz. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture [M]. New York: Rizzoli, 1980.

[2] Kenneth Frampton. Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance [M].//Kate Nesbitt(ed.) Theorizing a New Agenda for Architecture. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996:16-29.

[3] Vimolsiddhi Horayangkura et al. Pattanakarn Naewkwamkid Lae Roopbaeb Khong Sthapattayakam: Adeet Patchuban Lae Anakot [M]. Bangkok: The Association of Siamese Architects under Royal Patronage, 1993.

[4] M.L.Tridhosyudh Devakul. Directions in Thai Architecture [J]. ASA: Journal of the Association of Siamese Architects 1, 1972(9).

The Politics of Thai-ness

Architecture has long been recognized as the very embodiment of the identity and spirit of its dwellers. As we are buffeted by flow in the age of globalization however, the notion of "who we are" as a direct correlation to "where we are" becomes less and less distinct. In short, the notion of architecture as an expression of self and its cultural identity has never been more in question. Yet, when we look more closely, we begin to realize the nuances and details of our daily lives are still very much culturally situated. The "Thainess" in us is still at work in various ways, the very sense that does indeed manifest in many cultural and artistic outputs.The essay will look into the various manners by which this poetic of Thai-ness unveils.

cultural identity, Thai-ness, symbolic form, spatial experience, contemporary architecture

泰国朱拉隆功大学副教授,美国密歇根大学建筑历史与理论博士/Associate Professor of Chulalongkorn University, Thailand; Ph.D. in History and Theory of Architecture, University of Michigan.

2014-04-24