Safety issues in hormonal therapy

2013-10-25AlfredMueckRuanXiangyan

Alfred O.Mueck,Ruan Xiangyan

(1.University Women’s Hospital of Tuebingen,Centre of Women’s Health BW,Tuebingen D-72076,Germany;2.Department of Gynecological Endocrinology,Beijing Obstetricts and Gynecology Hospital,Capital Medical University,Beijing 100006,China)

Controversies about the safety of different hormone therapies have been existed for many years particularly regarding the use of hormonal contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy(HRT).Whereas for contraceptives newer studies especially investigating the risk of breast cancer have suggested only minimal risk[1-2],if at all,the discussion on HRT reached a peak after the publication of the Women’s Health Initiative(WHI)in 2003-2004[3-4].Besides the already known risk of venous thromboembolism,the WHI confirmed an increased risk of stroke and coronary heart disease,although this was relevant only with start of HRT in patients older than 60 years of age[5-6].

1 WHI-basis of official recommendations on HRT use

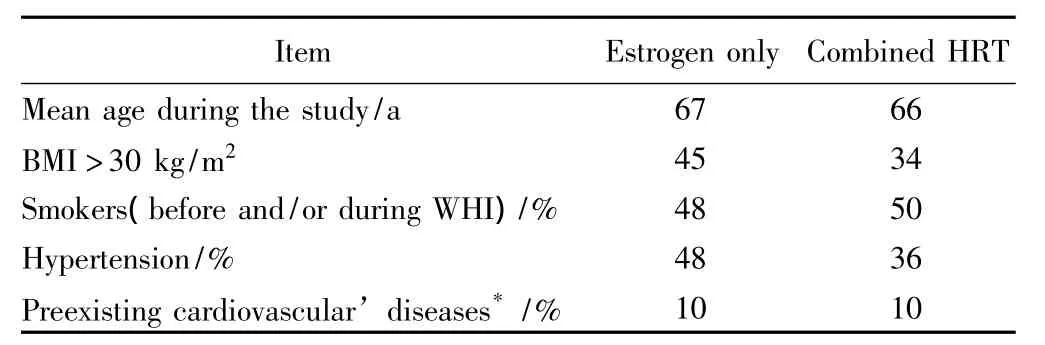

The WHI is the only study on HRT with placebocontrolled design,clinical endpoints and high statistical power due to a large patient sample.WHI was performed in two separate trials,in non-hysterectomized women(n=16 608)using conjugated equine estrogens(CEE)0.625 mg/d continuously combined with medroxyprogesterone acetate(MPA)2.5 mg/d(study 5 years),and in hysterectomized women(n=10 739)using CEE-only 0.625 mg/d(study 7 years).Although this study has been the basis of most official recommendations,like recently of the German guideline for the use of HRT[7],the WHI can not reflect the practical conditions,because on average the women were too old at start of HRT(about 65 years),and the population was at high risk particularly for cardiovascular diseases:Table 1 summarizes the main risk factors.

Tab.1 WHI-study-a population at high cardiovascular risks[3-4]

For younger women(under 60 years)no increased arterial risks have been observed correlating with about 40 observational trials as well as with hundreds of experimental studies,there was even a tendency to cardiovas-cular protection[5-6,8].However,these results have not been considered in most official guidelines because the study was not powered enough for subgroup evaluations.Nevertheless,based on the whole evidence there is a“window of opportunity”with more benefit compared to risk if HRT is early started within 5 ~10 years after menopause.For cardiovascular safety issues this is one of the most important points regarding practical use.

In the WHI only one HRT preparation was tested,and only in one dose-both also not reflecting practical conditions.At least in Europe we use various forms of therapies regarding type of hormones,dosage and application form.Although placebo-controlled studies for those preparations are lacking,for safety issues the evidence of observational and experimental studies should be considered suggesting that the main risks observed in WHI can be reduced,especially by use of transdermal HRT.

2 Reduction of cardiovascular risks by use of transdermal HRT

In contrary to USA in Europe since the 1980s,the non-oral administration of an estradiol replacement was available and recommended,especially for women with preexisting cardiovascular risk.The first obvious advantage is avoidance of the first liver passage which with oral estrogens in many circumstances is unfavourable for menopausal women.These include increased triglycerides,linked to a decrease in the size of lipoprotein(LDL)particles,to a higher level of C-reactive protein and activation of coagulation[9-12].This pharmacological,not“physiological”method of administration,on the one hand,reduces the anti-atherogenic effects of estradiol,and,on the other hand,can add risks of venous and arterial thromboembolism.

With regard to the main intermediate and wellknown risk markers(triglycerides,size of LDL particles,coagulation, C-reactive-protein), randomised studies have consistently confirmed the superiority of transdermal estradiol replacement to oral formulations,which makes plausible a real difference in the benefit/risk ratio between the two routes of administration[9-16].However,until now only few clinical endpoint studies have demonstrated this difference.

In a recent very large Danish study(n=698 098;aged 51-69)4,947 myocardial incidents have been identified[17].Overall,there was no increase of risk(RR=1.03,95%CI:0.95-1.11),but subgroups with oral HRT were assessed to be at increased risk.In contrast,with transdermal estrogen(patch or gel)a significant decrease of risk of about 40%was observed.No association were found with progestogen type or estrogen dose.Regarding the use in patients with angiographically proven ischemic heart disease only one small randomized study(PHASE)failed to demonstrate this potential safety improvement[18].However,this study had important limitations including the small sample size(n=255)and high dropout rate(40%in the HRT arm).

Regarding the risk of venous thromboembolism it is well established that oral estrogen therapy activates blood coagulation[10,13]and increases the risk of venous thromboembolism(VTE)in postmenopausalwomen[3-4,19]whereas transdermal estrogen has little or no effect on haemostasis[10,13,20].Randomised trials have shown that oral estrogen increased plasma level of prothrombin fragment F1+2,which is a marker for in vivo thrombin generation and a predictor of VTE risk[20-21],and APC resistance has been demonstrated using oral ET[22],which did not apply to transdermal application[23].

However,clinical data have been scarce although recent observational studies suggest that compared with oral HRT-with transdermal HRT the risk can be reduced[24-25],even in patients with preexisting high risk like with factor V Leiden mutation[26],which also is the conclusion of a recent meta analysis[27].For venous thrombotic risk also the choice of the progestogen could be important[28].The data suggest that progesterone and progestins from pregnane type may not enhance the thrombogenicity of orally administered estrogens(OR=0.7,95%CI:0.3-1.9)whereby pregnene derivatives may lead to a four-fold increased VTE risk(OR=3.9,95%CI:1.5-10.0).However,the important component seems to be the estrogen,and more data are needed to assess the risk attributed to the progestogen addition into HRT.

3 Risk of breast cancer-main mechanisms of hormonal effects

In contrast to cardiovascular risks it seems very clear that the main risk of breast cancer must be attributed to the progestogen component of HRT although at this time it is not possible to make conclusions on dependency of type,dosage and duration of the progestogen added to oral or transdermal estrogen therapy.

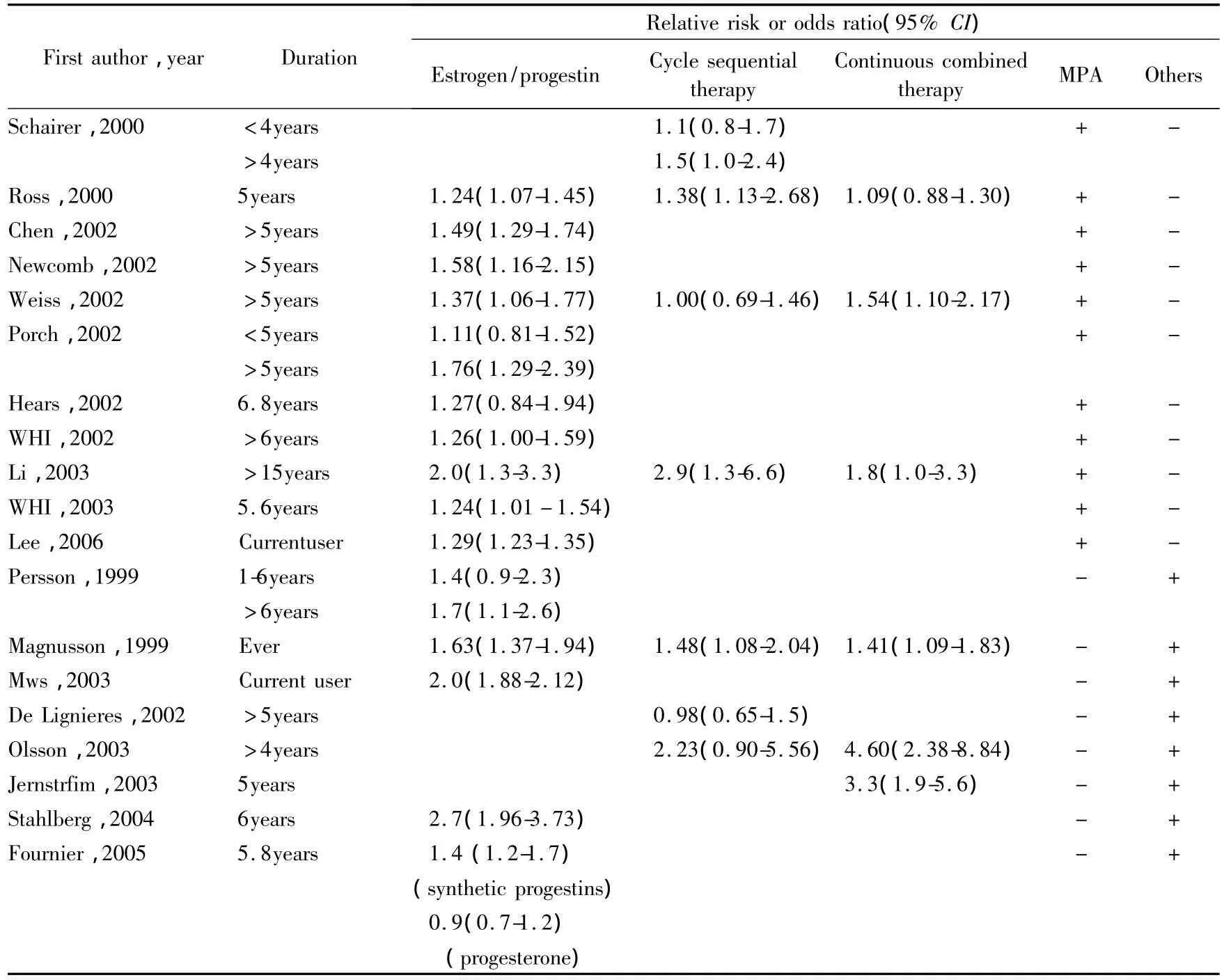

More than 60 studies on HRT and breast cancer have been conducted[29]and there is no doubt that the risk could increased with combined HRT,suggested in more than a dozen observational studies whereby mostly CEE combined with MPA or estradiol combined with norethisterone acetate at higher dosages have been used.Table 2 summarizes recent studies on this issue(reviewed[30]).

Tab.2 Epidemiological studies on breast cancer risk during estrogen plus progestin therapy

Until today the only placebo-controlled study,the WHI,demonstrated,that this risk is real if women are treated for more than five years(HR=1.24;95%CI:1.01-1.54)[31].But also with estrogen-only treatment an increased risk should not be excluded although this was not observed in the WHI(HR=0.77;95%CI:0.59-1.01)[4].In compliant women there was even a 30%significant reduction in risk of breast cancer(HR=0.67:95%CI:0.47-0.97),whereby the authors are discussing also mechanisms for this[32].However,at least 20 observational studies with estrogen-only therapy or with not well-defined regular progestogen addition(as often used in the earlier years)have demonstrated an increased risk[29],and mechanisms,as described as follows,seem to be plausible to explain this.

The main question,however,remains,if this increased risk,observed in clinical studies,depends on a causal relationship so far,that estrogens,alone or in combination with progestogens,may lead to cancer cells and may lead to an increased incidence of breast cancer patients,independent of other factors.

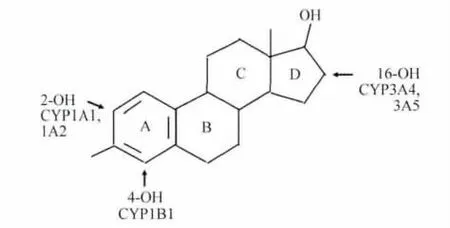

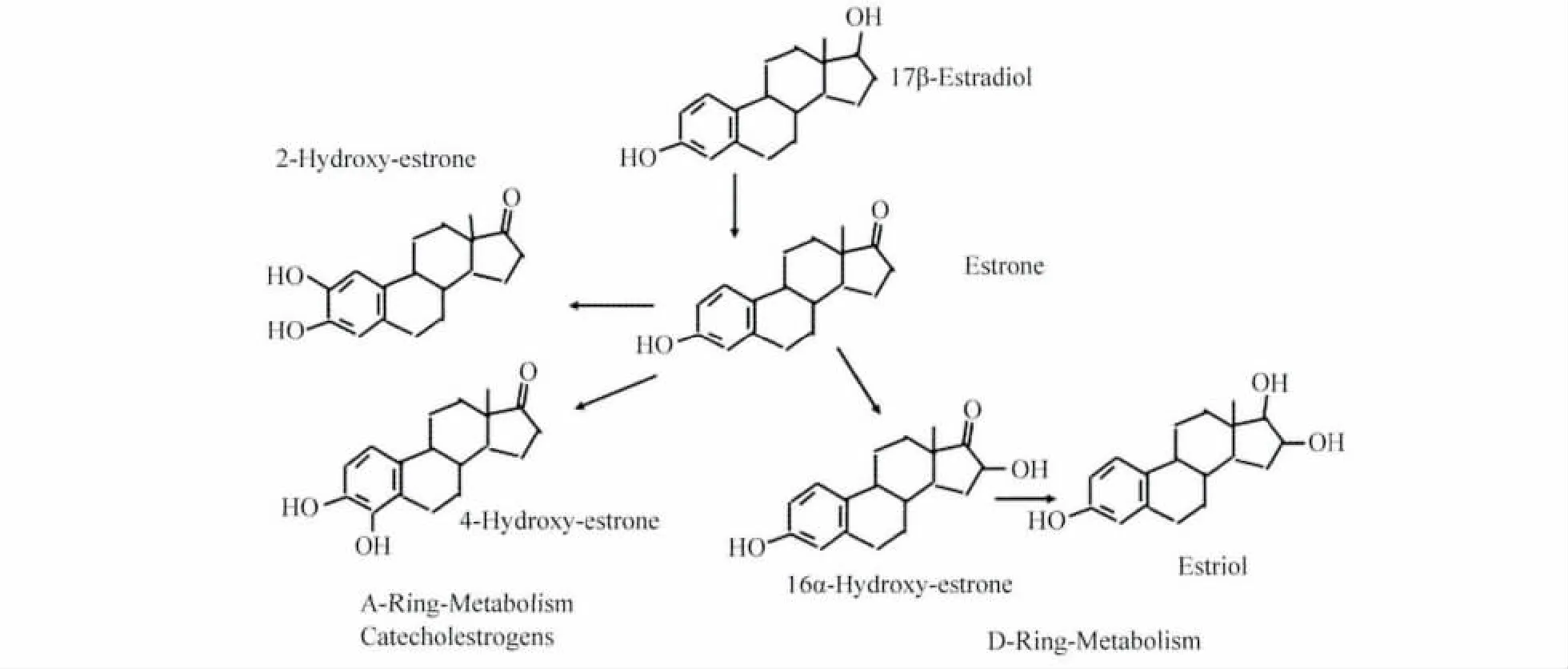

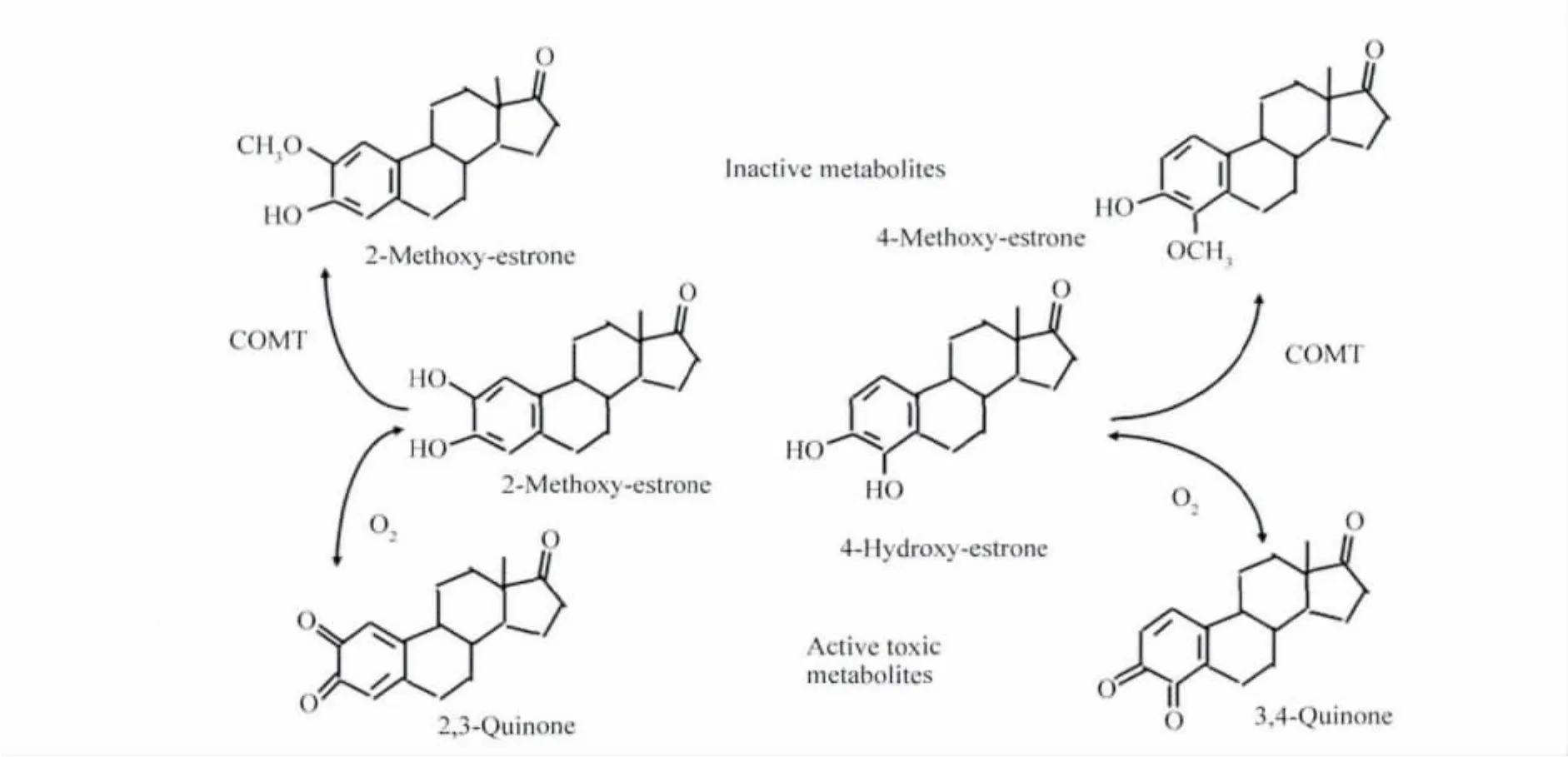

The World Health Organization(WHO),has defined estrogens and estrogen/progestogen combinations as“carcinogenic”[33].With respect to the component of all HRT preparations,the estrogen component,two main mechanisms have to be considered for the discussion of a potential carcinogenicity in the breast.The first main mechanisms are proliferation/apoptosis effects on already pre-existing estrogen-sensitive cancer cells,which could end in a clone of malignant cells large enough to be detected as‘breast cancer’in the clinical sense.This development needs at least 5-10 years according to the known doubling-times of most aggressive breast cancer cells.The second mechanism is derived from the fact,that estrogens can undergo excessive metabolism producing also biologically very active substances,even in low concentrations,which may lead to genotoxic effects producing new cancer cells(Fig.1 ,2,3)(reviewed[34-35])again,starting from those new cancer cells,to develop breast cancer clinically,the proliferation mechanisms would have to work for at least 5-10 years[36].

Fig.1 Nomenclature of steroid ring,17β-estradiolhydroxy-metabolites and main metabolizing enzyme of Cytochrome P450 family

Fig.2 Primary A-ring and D-ring estradiol metabolism

However,in special situations,also a decrease of breast cancer risk during hormones therapy can be derived from those mechanisms,e.g.by antiproliferative or apoptotic effects or by producing carcinoprotective estrogen metabolites,which perhaps can explain the significant decrease of breast cancer evaluating women compliant to the estrogen only therapy in the WHI[32].

Both mechanisms involve that the risk can be increased by adding to estrogen certain progestogens.However,according to our own experimental research[37-39],and likewise also in recent observational studies[40-43],there may be differences between the effects of progestogens in the breast with lesser risk using more natural progestogens like micronized progesterone or dydrogesterone,which is one of the most important topics of present research in the area of HRT.

And even if certain progestogens may increase the risk,it can be derived from experimental research,that this risk only would be true under very special,in general very rare conditions,correlating also with the low ab-solute excessive numbers of breast cancer in the range of 0.1%~0.5%assessed in clinical studies(like in WHI).

Fig.3 Secondary estradiol metabolism producing active toxic metabolites

In general,progestogens down-regulate target tissue estrogen receptors which should lead to a down-regulation of proliferation mechanisms.However,certain progestogens have been shown to elicit strong effects on stromaderived growth factors,which can have much stronger proliferating effects compared to estrogens,and there are differences in the actions in benign ormalignant cells[37-39].In addition certain progestogens may stimulate pathways of estrogen metabolism in the direction of potentially genotoxic metabolites[44].

The question for a causal relationship with breast cancer involves the production of new cancer cells followed by proliferation up to clinically detectable breast cancer.By proliferation mechanisms the production of a new cancer cell only seems to be possible in situations with disturbed reduplications of DNA leading to mutations,which indeed in vitro experiments have been found in case of very rapid proliferation[45-46].However,a whole battery of mechanisms can work to protect from reduplication errors.Whether these proliferating effects on normal epithelial cells may cause malignant transformation has not as yet been proven,although DNA repair is hampered by activated proliferation[45].

Regarding the importance of the second mechanism,via potential genotoxic estrogen metabolites,currently research focuses on the possible carcinogenic properties of 4-hydroxyestrogens[47].Animal experiments demonstrated a mutagenic effect of 4-hydroxyestrogen quinones[48].Elevated 4-hydroxylase enzyme activity has been found in human breast cancer specimens,and 4-hydroxyestradiol as well as the quinones were found in high concentrations in human breast cancer tissue[34].We have been able to demonstrate that estradiol metabolism during HRT can be influenced by administration route and type of progestin,whereby transdermal application of hormones may avoid the development of potential genotoxic metabolites due to low dosing and avoiding the first hepatic passage[44,49].

The prerequisite for destruction and/or mutation of DNA by estrogenic‘genotoxic’metabolites is that there has to be simultaneous cellular oxidative stress caused by additional factors like by smoking or by environmental factors,to produce free radicals,which lead to adducts of DNA,and further via depurination to destruction of the DNA.However,biochemically the crucial reaction between semiquinones and quinones is a so called‘Oneelectron-oxidation’,and the cells are extremely well protected against this,because this may indeed lead to new cancer cells,demonstrated with well known carcinogens like benzene,hexestrol or polycyclic carbons[50-53].

The toxic effects of 4-hydroxyestrogens can probably be prevented under normal conditions by various cellular defence mechanisms.The quinones themselves can be inactivated by sulfocompounds,such as the ubiquitous glutathione.Intracellularly formed catechol estrogens are rapidly methylated by the enzyme catechol orthomethyltransferase(COMT).However,for instance patients with a COMT defect due to genetic polymorphisms could be especially on risk of breast cancer during HRT,and similarly other polymorphisms of key enzymes in estrogen metabolites are discussed to increase the breast cancer risk,especially if there are cumulated defects.However,the clinical relevance still is under discussion,since those genetic changes are very rare[54-55].

4 Conclusion

Hormonal therapy has been used for more than 40 years for treatment of climacteric and urogenital symptoms and/or prevention of osteoporosis.The only placebo-controlled study evaluating clinical endpoints in large patient samples has demonstrated an increased risk of venous thromboembolism,myocardial infarction,stroke and breast cancer,but cannot reflect practical conditions since patients on average have been too old for HRT,and about 50%have had the main risk factors like heavy obesity,hypertension and/or were smokers.Although in absolute numbers the risks are low(about 0,1%per year),these risks may be important in women with risk factors or preexisting diseases.

There are options to minimize those risks like use of transdermal HRT or individualized choice of the progestogen component,or use of estrogen-only therapy,possible in hysterectomized women or with endometrial protection by levonorgestrel-intrauterine device(LNG-IUD).However,on the basis of biological plausibility regarding the underlying mechanisms perhaps no regimen can eliminate completely the risk of breast cancer during certain conditions like in women with already preexisting highlydeveloped breast cancer clones and/or in women with defects in detoxification systems,e.g.due to genetic polymorphisms of key enzymes.Our own and other new results of intensive research point out that additional factors are necessary to develop clinical breast cancer.

Thus there are important safety issues in hormonal therapy,but new options as well as new recent research suggest that on the basis of the WHI study the risks have been overestimated.Especially,if started early,in most patients the benefits should prevail,when indicated HRT is used properly.

5 Reference

[1]Marchbanks P A,McDonald J A,Wilson H G,et al.Oral contraceptives and the risk of breast cancer[J].N Engl J Med,2002,346(26):2025-2032.

[2]Hannaford P C,Selvaraj S,Elliott A M,et al.Cancer risk among users of oral contraceptives:cohort data from the Royal College of General Practitioner's oral contraception study[J].BMJ,2007,335(7621):651.

[3]WHI Investigators.Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women[J].JAMA,2002,288(3):321-333.

[4]WHI Steering Committee.Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy[J].JAMA,2004,291(14):1701-1712.

[5]WHI Investigators.Estrogen plus progestin and the risk of coronary heart disease[J].N Engl J Med,2003,349(6):523-534.

[6]WHI Investigators.Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease by age and years since menopause[J].JAMA,2007,297(13):1465-1477.

[7]Ortmann O(Leitlinienkoordination).Hormontherapie in der Peri-und Postmenopause.Kurzversion der interdisziplinären S3-Leitlinie[J].Frauenarzt,2009,50(11):840-851.

[8]WHI Investigators.Conjugated equine estrogens and coronary heart disease[J].Arch Intern Med,2006,166(3):357-365.

[9]Moorjani S,Dupont A,Labrie F.Changes in plasma lipoprotein and apolipoprotein composition in relation to oral vesrsus transdermal administration of estrogens[J].J Clin Endocrinol Metab,1991,73(2):373-379.

[10]Scarabin P Y,Alhenc-Gelas M,Plu-Bureau G,et al.Effects of oral and transdermal estrogen/progesterone regimens on blood coagulation and fibrinolysis in postmenopausal women.A randomized controlled trial[J].Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol,1997,17(11):3071-3078.

[11]Godsland I F.Effects of postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy on lipid,lipoprotein,and apolipoprotein(a)concentrations:analysis of studies published from 1974-2000[J].Fertil Steril,2001,75(5):898-915.

[12]Wakatsuki A,Okatani Y,Ikenoue N,et al.Different effects of oral conjugated equine estrogen and transdermal estrogen replacement on size and oxidative susceptibility of low-density lipoprotein particles in postmenopausal women[J].Circulation,2002,106(14):1771-1776.

[13]Vehkavaara S,Silveira A,Hakala-Ala-Pietila T,et al.Effects of oral and transdermal estrogen replacement therapy on markers of coagulation,fibrinolysis,inflammation and serum lipids and lipoproteins in postmenopausal women[J].Thromb Haemost,2001,85(4):619-625.

[14]Decensi A,Omodei U,Robertson C,et al.Effect of transdermal estradiol and oral conjugated estrogen on C-reactive protein in retinoid-placebo trial in healthy women[J].Circulation,2002,106(10):1224-1228.

[15]Modena M G,Bursi F,Fantini G,et al.Effects of hormone replacement therapy on C-reactive protein levels in healthy postmenopausal women:comparison between oral and transdermal administration of estrogen[J].Am J Med,2002,113(4):331-334.

[16]Sumino H,Ichikawa S,Ohyama Y,et al.Effect of transdermal hormone replacement therapy on the monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 concentrations and other vascular inflammatory markers and on endothelial function in postmenopausal women[J].Am J Cardiol,2005,96(1):148-153.

[17]Lokkegaard E,Andreasen A H,Jacobsen R K,et al.Hormone therapy and risk of myocardial infarction:a national register study[J].Eur Heart J,2008,29(21):2660-2668.

[18]Clarke S C,Kelleher J,Lloyd-Jones H,et al.A study of hormone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women with ischaemic heart disease:the Papworth HRT Atherosclerosis Study[PHASE][J].BJOG,2002,109(9):1056-1062.

[19]Hoibraaten E,Qvigstad E,Arnesen H,et al.Increased risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism during hormone repacement therapy-results of the randomized,double-blind,placebo-controlled estrogen in venousthromboembolism trial(EVTET)[J].Thromb Haemost,2000,84(6):961-967.

[20]Hoibraaten E,Mowinckel M C,de Ronde H,et al.Hormone replacement therapy and acquired resistance to activated protein C:results of a randomized,double-blind,placebo-controlled trial[J].Br J Haematol,2001,115(2):415-420.

[21]Tans G,van Hylckama Vlieg A,Thomassen M C,et al.Activated protein C resistance determined with a thrombin generation-based test predicts for venous thrombosis in men and women[J].Br J Haematol,2003,122(3):465-470.

[22]Hoibraaten E,Mowinckel M C,de Ronde H,et al.Hormone replacement therapy and acquired resistance to activated protein C:results of a randomized,double-blind,placebo-controlled trial[J].Br J Haematol,2001,115(2):415-420.

[23]Post M S,Christella M,Thomassen L G,et al.Effect of oral and transdermal estrogen replacement therapy on hemostatic variables associated with venous thrombosis:a randomized, placebo-controlled study in postmenopausal women[J].Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol,2003,23(6):1116-1121.

[24]Scarabin P Y,Oger E,Plu-Bureau G(for the ESTHER Study Group).Differential association of oral and transdermal oestrogen replacement therapy with venous thromboembolism risk[J].Lancet,2003,362(9382):428-432.

[25]Canonico M,Fournier A,Carcaillon L,et al.Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of idiopathic venous thromboembolism.Results from the E3N Cohort Study[J].Thromb Vasc Biol,2010,30(2):340-345.

[26]Straczek C,Oger E,de Jonage-Canonico M B Y,et al(for the ESTHER Study Group).Prothrombotic mutations,hormone therapy,and venous thromboembolism among postmenopausal women.Impact of the route of estrogen administration[J].Circulation,2005,112(22):3495-3500.

[27]Canonico M,Plu-Bureau G,Lowe G D O,et al.Hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women:a systematic review and meta-analysis[J].BMJ,2008,336(7665):1227-1231.

[28]Canonico M,Oger E,Plu-Bureau G,et al.Hormone therapy and venous thromboembolism among postmenopausal women.Impact of the route of estrogen administation and progestogens:The ESTHER Study[J].Circulation,2007,115(7):840-845.

[29]Beral V(Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer).Breast cancer and hormone replacement therapy:collaborative reanalysis of data from 51 epidemiological studies of 52.705 women with breast cancer and 108.411 women without breast cancer[J].Lancet,1997,350(9084):1047-1059.

[30]Seeger H,Mueck A O.HRT and breast cancer caused:Caused by progestogens?[J].J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol,2008,109(2):11-15.

[31]WHI Investigators.Influence of estrogen plus progestin on breast cancer and mammography in healthy postmenopausal women[J].JAMA,289(24):3243-3253.

[32]WHI Investigators.Effects of conjugated equine estrogens on breast cancer and mammography screening in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy[J].JAMA,2006,295(14):1647-1657.

[33]Cogliano V,Grosse Y,Baan R,et al(WHO International A-gency for Research on Cancer,IARC).Carcinogenicity of combined oestrogen-progestagen contraceptives and menopausal treatment[J].Lancet Oncol,2005,6(4):552-553.

[34]Rogan E G,Badawi A F,Devanesan P D,et al.Relative imbalances in estrogen metabolism and conjugation in breast tissue of women with carcinoma:potential biomarkers of susceptibility to cancer[J].Carcinogenesis,2003,24(4):697-702.

[35]Mueck A O,Seeger H.Breast cancer:are oestrogen metabolites carcinogenic?[J].Maturitas,2007,57(1):42-46.

[36]Dietel M,Lewis M A,Shapiro S.Hormone replacement therapy:pathobiological aspects of hormone-sensitive cancers in women relevant to epidemiological studies on HRT:a mini-review[J].Hum Reprod,2005,20(8):2052-2060.

[37]Mueck A O,Seeger H,Wallwiener D.Comparison of the proliferative effects of estradiol and conjugated equine estrogens on human breast cancer cells and impact of continuous combined progestogen addition[J].Climacteric,2003,6(3):221-227.

[38]Krämer E,Seeger H,Krämer B,et al.The effects of progesterone and synthetic progestogens on growth factor and estradiol treated human cancerous and non-cancerous breast cells[J].Menopause,2005,129(1):468-474.

[39]Neubauer H,Adam G,Seeger H,et al.Membrane-initiated effects of progesterone on proliferation and activation of VEGF in breast cancer cells[J].Climacteric,2009,12:230-239.

[40]de Lignieres B,de Vathaire F,Fournier S,et al.Combined hormone replacement therapy and risk of breast cancer in a French cohort study of 3 175 women[J].Climacteric,2002,5(4):332-340.

[41]Fournier A,Berrino F,Clavel-Chapelon F.Unequal risks for breast cancer associated with different hormone therapies:results from the E3N cohort study[J].Breast Cancer Res Treat,2008,107(1):103-111.

[42]Opatrny L,Dell'Aniello S,Assouline S,et al.Hormone replacement therapy and variations in the risk of breast cancer[J].BJOG,2008,115(1):169-175.

[43]Lyytinen H,Pukkala E,Ylikorkala O.Breast cancer risk in postmenopausal women using estradiol-progestogen therapy[J].Obstet Gynecol,2009,113(1):65-73.

[44]Seeger H,Mueck A O,Lippert T H.Effect of norethisterone acetate on estradiol metabolism in postmenopausal women[J].Horm Metab Res,2000,32(10):436-439.

[45]Henderson B E,Feigelson H S.Hormonal carcinogenesis[J].Carcinogenesis,2000,21(3):427-433.

[46]Seeger H,Wallwiener D,Krämer E,et al.Comparison of possible carcinogenic estradiol metabolites:Effects on proliferation,apoptosis and metastasis of human breast cancer cells[J].Maturitas,2006,54(1):72-77.

[47]Liehr J G,Ricci M J.4-Hydroxylation of estrogens as marker of human mammary tumors[J].Proc Natl Acad Sci USA,1996,93(8):3294-3296.

[48]Chakravarti D,Mailander P C,Higginbotham S.The catechol estrogen-3,4-quinone metabolite induces mutations in the mammary gland of ACI rats[J].Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res,2003,44(4):180-186.

[49]Lippert T H,Seeger H,Mueck A O.Estradiol metabolism during oral and transdermal estradiol replacement therapy in the postmenopause[J].Horm Metab Res,1998,30(9):598-600.

[50]Bolton J L,Pisha E,Zhang F,et al.Role of quinoids in estrogen carcinogenesis[J].Chem Res Toxicol,1998,11(10):1113-1127.

[51]Liehr J G,Roy D.Free radical generation by redox cycling of estrogens[J].Free Radic Biol Med,1990,8(4):415-423.

[52]Mueck A O,Seeger H.Smoking,estradiol metabolism and hormone replacement therapy[J].Drug Res,2003,53(1):1-11.

[53]Berstein L M,Tsyrlina E V,Kolesnik O S,et al.Catecholestrogens excretion in smoking and non-smoking postmenopausal women receiving estrogen replacement therapy[J].J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol,2000,72(3-4):143-147.

[54]Dunning A M,Healey C S,Pharoah P D P,et al.A systematic review of genetic polymorphisms and breast cancer risk[J].Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev,1999,8(16):843-854.

[55]Bugano D D,Conforti-Froes N,Yamaguchi N H,et al.Genetic polymorphisms,the metabolism of estrogens and breast cancer:a review[J].Eur J Gynaecol Oncol,2008,29(4):313-320.