干细胞治疗终末期肝病的进展与挑战

2013-08-28施明刘振文张政王福生

施明,刘振文,张政,王福生

肝移植是治疗终末期肝病最有效的方法,但供肝来源短缺与肝移植需求之间的巨大差距促使人们努力寻求其他的替代疗法。近来,干细胞治疗终末期肝病越来越受到关注,特别是骨髓来源的干细胞[主要含造血干细胞(HSC)和间质干细胞(MSC)]治疗已有体外和动物实验支持,自体回输骨髓干细胞治疗亦有相关临床报道。此外,其他来源的MSC治疗肝病亦取得了较好进展。本文就此方面的研究进展综述如下。

1 研究背景

干细胞根据其发育阶段可分为胚胎干细胞(ES)和成体干细胞,其重要特征是具有无限自我更新能力,可以分化成特定组织,在细胞发育过程中处于较原始阶段。骨髓是成体干细胞的重要来源,主要含HSC和MSC。MSC在骨髓中含量最多,在其他组织器官如脐带组织﹑脐带血﹑胎盘﹑外周血﹑脂肪组织中的含量也较丰富。基于干细胞强大的分化潜能,人们开始尝试应用干细胞治疗各种疾病。自1999年Petersen等[1]发现骨髓中某些干细胞具有向肝细胞分化的潜能以来,人们开始研究应用干细胞治疗肝病的可行性,后来发现不同来源的干细胞如骨髓HSC﹑骨髓MSC等均可定向诱导分化为肝细胞样细胞,具有正常肝细胞功能,如分泌尿素和白蛋白等[2],且得到动物实验的验证,临床亦有自体回输骨髓干细胞治疗肝病的报道。目前开展的肝病治疗研究的干细胞类型如图1所示。

图1 目前已经开展的治疗肝病的干细胞类型及其治疗机制Fig.1 Types of stem cells on current liver disease therapy and its mechanism

2 临床前研究

2.1 骨髓干细胞治疗肝病 以前认为只有具备HSC特性的细胞才能转化为肝细胞,1999年Petersen等[1]发现骨髓干细胞或HSC能够在鼠肝内转化为肝卵圆细胞甚至成熟的肝细胞和胆管细胞。2000年Theise等[3]在异性间骨髓移植或肝移植的受体中也发现了源于供体的肝细胞和胆管细胞。Lagasse等[4]用正常小鼠骨髓细胞移植治疗延胡索酰乙酰乙酸盐水解酶缺乏(FAH-/-)导致的遗传性Ⅰ型酪氨酸血症小鼠,发现骨髓中只有HSC能在体内转分化为肝细胞,并在受体内形成供体源造血和肝细胞再生,受体小鼠血液生化指标明显改善。之后,人们尝试应用粒细胞集落刺激因子(G-CSF)直接动员骨髓释放干细胞来治疗肝病。动物部分肝切除后应用G-CSF可以促进肝再生,其机制可能与血液中CD133+或CD34+细胞动员有关,且体外培养G-CSF动员后CD133+细胞可表达肝细胞特异性标志物[5]。为进一步验证CD133+细胞对肝再生的促进作用,am Esch等[6]将分选出的自体骨髓CD133+细胞回输至选择性门静脉栓塞的中央巨型肝脏肿瘤患者中,发现CD133+细胞移植组非栓塞部分肝脏体积明显增大,有利于患者接受进一步手术。

Sakaida等[7]应用四氯化碳(CCl4)建立的小鼠肝纤维化模型进行研究发现,异体骨髓细胞移植能减轻肝纤维化程度,提高小鼠生存率。大鼠未受损的肝血窦内皮细胞上有HSC表面标志(CD45+和CD33+)及内皮细胞的表面标志(CD31+),肝血窦内皮细胞受损后,回输骨髓来源的CD133+干细胞,在受体肝脏中可发现供体来源的肝血窦内皮细胞,替代了原来的受损细胞[8]。

也有部分学者对HSC向肝细胞分化的潜能及治疗意义提出了质疑,他们应用动物的骨髓造血祖细胞在体外并不能诱导成功能性的肝细胞[9],应用转基因的HSC研究发现,在体内只有极少部分HSC来源的肝细胞与受体的肝细胞形成融合细胞,几乎没有任何治疗意义[10]。

2.2 MSC治疗肝病 由于骨髓细胞成分复杂,何种细胞更适合用于肝细胞再生治疗尚不清楚,但越来越多的研究倾向于骨髓MSC。Sato等[11]比较了人骨髓中的MSC﹑CD34+﹑非MSC/CD34–等3种细胞直接注射到大鼠肝内后转分化成肝细胞的能力,结果骨髓MSC显示出最强的向肝细胞分化的潜能。

在适当条件尤其是肝脏损伤的情况下,骨髓MSC可以分化为肝细胞样细胞,这些分化细胞表现出成熟肝细胞的形态和特征,如表达肝细胞特异性基因,具有合成和分泌白蛋白﹑储存糖原﹑代谢尿素及解毒功能等。Kuo等[12]应用人骨髓来源的MSC进行移植治疗,使小鼠暴发型肝衰竭得到有效恢复,并促进了肝脏的再生。脂肪组织来源的MSC与骨髓来源的MSC相似,在体外可诱导成肝细胞样细胞,将这些肝细胞样细胞移植到CCl4肝损伤模型的小鼠体内,可整合入宿主的肝脏中,使其肝脏功能得到改善[13-14]。Van Poll等[15]应用D-半乳糖胺建立小鼠急性肝损伤模型,再输入MSC条件培养基(MSC-CM),结果有效地减少了肝细胞坏死,促进了肝细胞增殖,并抑制了肝损伤标志物的释放。Chamberlain等[16]将人MSC分别通过腹腔和肝内注射至胎羊中,发现经肝内途径注射MSC后,人来源的肝细胞广泛分布于肝实质中,而通过腹腔途径注射MSC后,人来源的肝细胞主要分布于门静脉周围。用人羊水来源的MSC,以及由MSC诱导分化的肝祖细胞样细胞和肝细胞样细胞治疗CCl4损伤的急性肝衰竭动物模型,结果羊水来源的MSC和肝祖细胞样细胞取得了很好的治疗效果,且回输肝祖细胞样细胞条件培养基也能取得较好效果[17]。人肝干细胞及其条件培养基对暴发性肝衰竭也有很好的保护作用,可通过分泌细胞因子抑制肝细胞凋亡,促进肝细胞再生[18]。最近国内有学者研究发现,通过门静脉输注人骨髓来源的MSC可提高急性肝衰竭猪的生存率,促进肝细胞再生[19]。

但同时也有研究表明,MSC不能在体外诱导成成熟的肝细胞,但可在体内分化为肝细胞,且免疫原性很低,是MSC治疗肝病的良好细胞来源[20]。将人骨髓来源的MSC直接注入免疫抑制的肝脏损伤大鼠中,其分布只限于注射部位周围,虽然可以分化成肝细胞,但分化效率很低,且供体的MSC并不与受体的肝细胞发生融合,MSC分化的肝细胞单纯来源于供体MSC[11]。Arikura等[21]将先天性白蛋白缺乏症大鼠行70%肝切除后植入正常大鼠骨髓MSC,4周后在受体肝脏中可检测到表达白蛋白mRNA的肝细胞。

2.3 胚胎干细胞(ES)治疗肝病 ES是指从囊胚期的内细胞团中分离出来的尚未分化的胚胎细胞,可分化形成各种类型的组织[22]。ES具有在体外无限增殖并保持分化成所有细胞类型的特性,理论上可以向3个胚层的任何类型细胞分化,其中也包括肝细胞[23-25]。已有研究表明ES对大鼠肝衰竭[26]和小鼠肝硬化[27]均有显著疗效。目前,有关ES研究的限制主要集中在伦理学﹑组织相容性以及移植后畸胎瘤发生等方面。

2.4 诱导多能干细胞(iPS)治疗肝病 已有研究显示iPS细胞可以诱导分化为肝细胞[28],也可将人原代肝细胞重编程为肝细胞来源的iPS细胞,此iPS细胞可定向诱导分化为内胚层细胞﹑肝祖细胞和成熟的肝细胞[29]。有研究发现小鼠iPS细胞可以在四倍体囊胚中发育成完整的胎肝,同时人iPS细胞可在体外诱导分化为具备相关功能的肝细胞样细胞,这些细胞可以在小鼠的肝脏内增殖并整合到肝实质中[30]。最近发现应用三种转录因子(缺少转录因子c-Myc)的iPS细胞及其诱导的具肝细胞表型和功能的肝细胞样细胞,均能减轻CCl4所致的急性肝损伤,提高动物生存率[31]。有研究者建立了以代谢性疾病患者真皮成纤维细胞制备的人iPS细胞系平台,此iPS细胞系能诱导分化成具有肝细胞表型﹑基因型和功能的肝细胞样细胞,显示出较强的治疗潜力[32]。利用iPS细胞治疗肝病的具体疗效及其安全性尚需在动物模型中进一步验证。

3 临床研究

3.1 HSC治疗肝病的临床研究 2000年Alison等[33]在移植了男性骨髓细胞的女性患者肝脏内发现了Y染色体阳性的肝细胞,2002年Korbling等[34]在移植了男性外周血干细胞的女性患者肝脏内也发现了来自男性的肝细胞,证明骨髓和外周血干细胞在人体内可以分化为肝细胞。骨髓干细胞治疗可以通过G-CSF动员或直接抽取骨髓的方式进行。

3.1.1 G-CSF动员的骨髓干细胞 Gaia等[35]应用G-CSF动员骨髓干细胞治疗终末期肝病,患者有较好的耐受性,部分患者Child和终末期肝病模型(MELD)评分改善,临床症状好转。Garg等[36]应用G-CSF动员骨髓CD34+干细胞治疗慢加急性肝衰竭,结果患者耐受性良好,Child﹑MELD和序贯器官衰竭估计(SOFA)评分均显著改善,生存率显著提高。Levicar等[37]应用G-CSF动员骨髓,通过免疫磁珠分选外周血中的CD34+干细胞,并通过门静脉或肝动脉回输治疗慢性肝衰竭,结果未发现短期和长期不良反应,患者的肝脏功能有一定程度改善。Salama等[38]应用G-CSF动员骨髓,而后通过收集外周血中的骨髓HSC治疗终末期肝病,结果患者白蛋白升高,胆红素和丙氨酸转氨酶(ALT)下降,国际标准化比值(INR)恢复正常,所有患者均耐受。但也有报道通过门静脉回输自体骨髓CD133+细胞和单个核细胞治疗失代偿性肝硬化效果均不十分理想[39]。

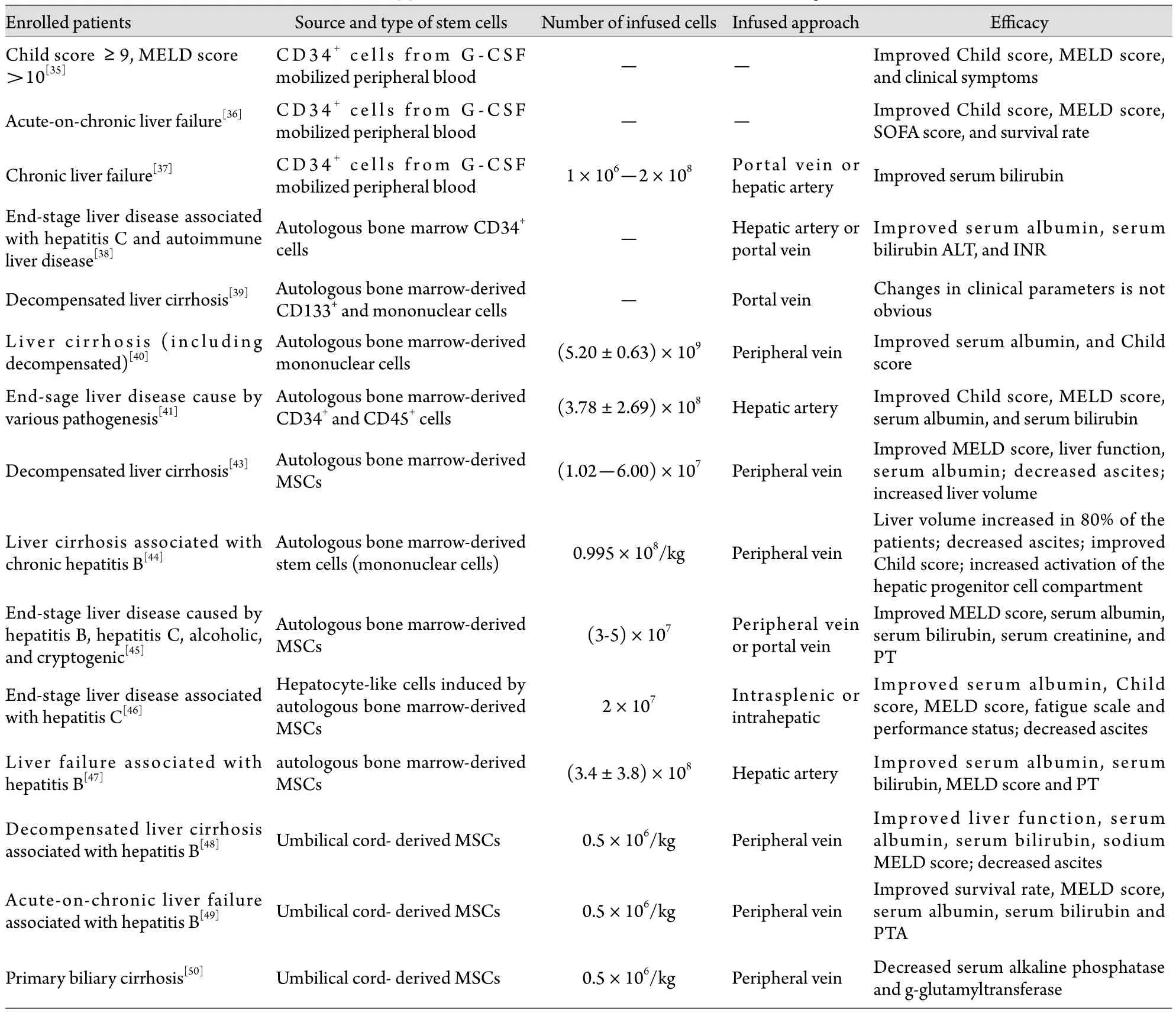

3.1.2 未经动员的骨髓干细胞 Terai等[40]通过骨髓穿刺获取骨髓干细胞后,经外周静脉回输治疗肝硬化(包括失代偿),在24周随访期内,患者血浆白蛋白水平明显升高,Child评分明显改善,肝脏活检组织中甲胎蛋白(AFP)及增殖细胞核抗原(PCNA)水平明显升高。Lyra等[41-42]分离终末期肝病患者骨髓单个核细胞后经肝动脉回输,结果无明显不良反应,患者Child﹑MELD评分明显改善,血清总胆红素下降,白蛋白升高,INR明显下降,通过肝动脉回输骨髓干细胞治疗终末期肝病安全可行。Mohamadnejad等[43]采用抽取自体骨髓体外培养的方法,将富含干细胞标记的细胞亚群回输至等待肝移植的患者,4例患者在等待期内均存活,1年内MELD评分有所改善。Kim等[44]应用自体骨髓干细胞(包括造血干细胞和上皮细胞等单核细胞)治疗慢性乙肝相关的肝硬化患者,结果患者生活质量明显改善,80%患者肝脏体积增大,腹水减少,Child评分改善,肝脏祖细胞(HPC)活性增强,可在6个月继续分化成肝细胞,但肝硬化的临床分级无明显改善(表1)。

3.2 MSC治疗肝病的临床研究 Mohamadnejad等[43]最早报道应用自体骨髓MSC治疗终末期肝病患者,经穿刺获取骨髓后通过密度梯度离心获得骨髓单个核细胞,在体外诱导成MSC后,经外周静脉回输至患者,经过12个月的随访,该方法安全无副作用,患者症状明显改善,血浆白蛋白升高,腹水减少,肝体积增大,MELD评分改善。Khayaziha等[45]报道应用自体骨髓MSC经外周或门静脉回输治疗由乙肝﹑丙肝﹑酒精性肝硬化及不明原因导致的终末期肝病患者,结果表明该方法安全无副作用,能提升血浆白蛋白,降低胆红素水平,促进凝血酶原时间(PT)复常,改善MELD评分。近两年Amer等[46]用骨髓MSC体外诱导成肝细胞样细胞后进行自体回输治疗丙肝相关的终末期肝病,结果患者症状明显改善,腹水减少,白蛋白显著增加,Child和MELD评分改善。

国内学者最近应用MSC治疗终末期肝病取得了较好进展。Peng等[47]应用自体骨髓MSC治疗乙肝相关的肝衰竭患者,结果短期(4周)内患者白蛋白﹑PT水平明显增加,而总胆红素水平和MELD评分明显下降,无明显不良反应,但长期效果不明显。Zhang等[48]应用脐带MSC移植治疗慢性乙肝相关失代偿性肝硬化,结果患者腹水明显减少,肝脏功能明显改善,白蛋白增加,血清胆红素水平和MELD评分明显下降。Shi等[49]应用脐带MSC移植治疗慢性乙肝相关的慢加急性肝衰竭患者,结果发现可显著提高患者生存率,改善MELD评分,增加白蛋白﹑胆碱酯酶﹑凝血酶原活动度水平,而总胆红素和转氨酶水平明显下降。Wang等[50]采用脐带MSC治疗原发性胆汁性肝硬化患者,结果血清胆碱磷酸和γ-谷氨酰转移酶水平明显下降(表1)。

表1 干细胞治疗终末期肝病的临床应用情况Tab. 1 Clinical application of stem cells on treatment of end-stage liver disease

3.3 干细胞回输与移植途径 目前,干细胞治疗肝病的主要移植途径有外周循环移植﹑门静脉移植﹑肝动脉移植等,现有的结果显示安全性好,患者可耐受,无明显不良反应。但也有报道经穿刺获得骨髓后应用免疫磁珠分选出CD34+干细胞,经过肝动脉回输,结果发生显影剂性肾病,最后发展成1型肝肾综合征[51]。因此,通过肝动脉回输干细胞的安全性尚需进一步观察。

3.4 疗效评价及影响疗效的因素 移植前的肝功能状况直接影响干细胞移植的结局。Barba等[52]报道HSC移植前高胆红素和高谷酰转肽酶(GGT)水平可影响移植后病死率和生存率。现有肝功能改善的评价方法主要包括Child和MELD评分﹑血液生化﹑临床表现﹑生活质量﹑生存时间(率),以及应用甲胎蛋白和PCNA评价肝细胞再生,利用TNF﹑IL-6和IL-10等评价肝脏炎症环境的改善等[53]。利用磁性标记的大鼠MSC进行肝脏移植,再行磁共振成像活体示踪,可在肝实质中发现标记的移植细胞[54]。肝组织活检对评价肝再生及移植细胞状态有重要意义,但有创性使其对终末期肝病患者的应用受到限制。一些无创或微创的活体内移植细胞示踪方法如Y染色体探查等,可应用于不同性别间的细胞移植,放射性同位素标记移植细胞后应用核素显像或PET-CT等也已有临床报道[55]。这些方法均可在不同程度上说明移植细胞的存活和增殖情况,为评价干细胞移植的作用提供依据。

4 干细胞治疗肝病的机制

4.1 干细胞归巢功能 肝脏微环境改变是MSC归巢的始动因素,肝组织损伤时存在炎症反应,局部可表达及分泌多种趋化因子﹑黏附因子﹑生长因子﹑基质金属蛋白酶9(MMP-9)等,这些因子与其受体的相互作用可引导干细胞特异性迁移至病损部位[56-58]。基质细胞衍生因子SDF-1及其受体CXCR4构成的SDF-1/CXCR4轴是引导MSC向损伤组织迁移的重要生物轴[59]。此外,肝细胞生长因子(HGF)及其受体c-met构成的HGF/c-met轴﹑G-CSF﹑血管内皮生长因子(VEGF)﹑MMP等均与MSC的归巢有关[58,60-61]。还有研究认为,肝脏受损后肝脏环境中的鞘脂代谢物——鞘氨醇1-磷酸盐(S1P)水平增高,且其与骨髓之间的浓度梯度差通过S1P3受体介导是骨髓MSC向肝脏归巢的重要因素[62]。

4.2 干细胞分化功能 Petersen等[1]于1999年首先报道,在性别交叉骨髓细胞移植或全肝移植受体肝脏中发现来源于供体骨髓的肝细胞,随后Alison等[33]和Theise等[3]相继发现骨髓移植和肝移植患者的肝脏中也有来源于供体骨髓的肝细胞。Lagasse等[4]在延胡索酰乙酰乙酸水解酶(FAH)缺陷大鼠模型中发现骨髓HSC可在肝脏内分化为具有功能的肝细胞,改善FAH缺陷大鼠的症状。Schwartz等[63]也报道,从大鼠﹑小鼠和人的骨髓中分离得到多能成体祖细胞,体外经成纤维细胞生长因子(FGF)和HGF诱导可分化为功能肝细胞。骨髓中存在可分化为肝细胞的干细胞,直接将其移植到肝脏,在肝脏微环境下可分化为肝细胞。因此骨髓干细胞移植为多种严重肝病的治疗提供了新的策略(图1)。

MSC具有跨胚层多向分化潜能,在合适的条件下,如HGF﹑FGF﹑表皮生长因子(EGF)或制瘤素M(OSM)等诱导下,通过特定的细胞信号传导途径,可以跨胚层向内胚层的肝细胞样细胞﹑胆管细胞和血管内皮样细胞分化[64-66],而Notch/Jagged信号通路在此过程中可能起重要作用[67-68]。在此分化系统中,肝脏局部微环境,如细胞因子﹑细胞外基质(ECM)﹑激素﹑基质细胞等,是诱导MSC定向分化的决定因素,其中细胞因子的类型﹑浓度和添加次序是影响MSC分化的主要因素[69]。

4.3 干细胞旁分泌功能 以往认为,干细胞移植可提供大量肝细胞样细胞替代受损的肝细胞功能,然而急性肝损伤所造成的疾病进展快,肝功能恢复不能依赖于干细胞分化为肝细胞过程,而更大程度上依赖其他机制,目前认为干细胞旁分泌机制改变组织微环境比向肝细胞的转分化更重要[70]。如MSC可以分泌多种细胞因子﹑生长因子,发挥局部效应,促进受损肝脏增生及肝脏血管再生,抑制免疫细胞增殖及向肝脏迁移,调节肝脏及全身免疫炎症反应,从而减轻肝脏的急性损伤,提高生存率[12,71-72]。MSC的条件培养基能抑制肝细胞的抗凋亡,刺激肝脏再生[15],机制可能与MSC的旁分泌功能一致,即为损伤的肝脏提供营养和有利的生存环境,因为蛋白质组分析显示条件性培养基中含有许多抗炎症因子,如IL-10﹑IL-1ra﹑IL-13和IL-27等[17],以及促进肝细胞再生﹑抑制肝细胞凋亡的细胞因子,如HGF﹑IL-10﹑VEGF﹑IL-6和IL-8等[18]。此外,研究还发现移植的骨髓MSC可通过释放促细胞增生因子和MMP-9刺激内源性肝细胞再生[73-74]。

5 存在的问题与展望

基于干细胞具有自我更新﹑无限增殖的能力以及多向分化潜能的特性,将其应用于终末期肝病的临床研究取得了令人鼓舞的进展,但干细胞治疗终末期肝病的长期安全性(特别是致畸或癌变的风险)和远期疗效仍有待观察,在疗效评价方面如何检测受体肝脏内移植细胞的状态和功能,如何减少和避免排斥反应及其他不良反应,特别是MSC具有形成肝细胞或促进肝纤维化的双刃剑作用[75],仍需进一步探讨。此外,干细胞的来源﹑诱导培养条件﹑细胞质量控制(包括表型﹑功能﹑微生物安全)﹑使用时机﹑途径和剂量﹑临床适应证等都可能对治疗的后果产生影响,这一系列与安全和疗效密切相关的问题还须进一步深入研究。因此,要在阐明其机制的基础上,不断积累各方面的资料,明确其临床应用的安全性和有效性,保证患者利益。

总之,干细胞强大的治疗潜力有可能成为终末期肝病患者的有效治疗手段,从而给患者带来新的希望。

[1] Petersen BE, Bowen WC, Patrene KD, et al. Bone marrow as a potential source of hepatic oval cells[J]. Science, 1999,284(5417): 1168-1170.

[2] Jiang Y, Jahagirdar BN, Reinhardt RL, et al. Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow[J]. Nature,2002, 418(6893): 41-49.

[3] Theise ND, Nimmakayalu M, Gardner R, et al. Liver from bone marrow in humans[J]. Hepatology, 2000, 32(1): 11-16.

[4] Lagasse E, Connors H, AL-Dhaling M, et al. Purified hematopoietic stem cells can differentiate into hepatocytes in vivo[J]. Nat Med, 2000, 6 (11): 1229-1234.

[5] Gehling UM, Willems M, Dandri M, et al. Partial hepatectomy induces mobilization of a unique population of haematopoietic progenitor cells in human healthy liver donors[J]. J Hepatol,2005, 43(5): 845-853.

[6] am Esch JS 2nd, Knoefel WT, Klein M, et al. Portal application of autologous CD133+ bone marrow cells to the liver: a novel concept to support hepatic regeneration[J]. Stem Cells, 2005,23(4): 463-470.

[7] Sakaida I, Terai S, Yamamoto N, et al. Transplantation of bone marrow cells reduces CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in mice[J].Hepatology, 2004, 40(6): 1304-1311.

[8] Harb R, Xie G, Lutzko C, et al. Bone marrow progenitor cells repair rat hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cells after liver injury[J].Gastroenterology, 2009, 137(2): 704-712.

[9] Lian G, Wang C, Teng C, et al. Failure of hepatocyte marker expressing hematopoietic progenitor cells to efficiently convert into hepatocytes in vitro[J]. Exp Hematol, 2006, 34(3): 348-358.[10] Yamaguchi K, Itoh K, Masuda T, et al. In vivo selection of transduced hematopoietic stem cells and little evidence of their conversion into hepatocytes in vivo[J]. J Hepatol, 2006, 45(5):681-687.

[11] Sato Y, Araki H, Kato J, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells xenografted directly to rat liver differentiated into hepatocytes without fusion[J]. Blood, 2005, 106(2): 756-763.

[12] Kuo TK, Hung SP, Chuang CH, et al. Stem cell therapy for liver disease: parameters governing the success of using bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells[J]. Gastroenterology, 2008, 134(7):2111-2121.

[13] Banas A, Teratani T, Yamamoto Y, et al. Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells as a source of human hepatocytes[J].Hepatology, 2007, 46(1): 219-228.

[14] Taléns-Visconti R, Bonora A, Jover R, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells from adipose tissue: differentiation into hepatic lineage[J]. Toxicol In Vitro, 2007, 21(2): 324-329.

[15] Van Poll D, Parekkadan B, Cho CH, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell derived molecules directly modulate hepatocellular death and regeneration in vitro and in vivo[J]. Hepatology, 2008, 47(5):1634-1643.

[16] Chamberlain J, Yamagami T, Colletti E, et al. Efficient generation of human hepatocytes by the intrahepatic delivery of clonal human mesenchymal stem cells in fetal sheep[J]. Hepatology,2007, 46(6): 1935-1945.

[17] Zagoura DS, Roubelakis MG, Bitsika V, et al. Therapeutic potential of a distinct population of human amniotic fluid mesenchymal stem cells and their secreted molecules in mice with acute hepatic failure[J]. Gut, 2012, 61(6): 894-906.

[18] Sanchez MB, Fonsato V, Bruno S, et al. Human liver stem cells improve liver injury in a model of fulminant liver failure[J].Hepatology, 2013, 57(1): 311-319.

[19] Li J, Zhang LY, Xin JJ, et al. Immediate intraportal transplantation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells prevents death from fulminant hepatic failure in pigs[J]. Hepatology, 2012,56(3): 1044-1052.

[20] Campard D, Lysy PA, Najimi M, et al. Native umbilical cord matrix stem cells express hepatic markers and differentiate into hepatocyte-like cells[J]. Gastroenterology, 2008, 134(3): 833-848.

[21] Arikura J, Inagaki M, Huilin g X, et al. Colonization of albuminprodusing hepatocytes derived from transplanted F344 rat bone marrow cells in the live of congenic Nagase's anabuminemic rats[J]. J Hepatol, 2004, 41(2): 215-221.

[22] Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts[J]. Science,1998, 282(5391): 1145-1147.

[23] Chinzei R, Tanaka Y, Shimizu-Saito K, et al. Embryoid body cells derived from amouse embryonic stem cell line show differentiation into functional hepatocytes[J]. Hepatology, 2002,36(1): 22-29.

[24] Yin Y, Lim YK, Salto-Tellez M, et al. AFP(+), ESC derived cells engraft and differentiate into hepatocytes in vivo[J]. Stem Cells,2002, 20(4): 338-346.

[25] Heo J, Factor VM, Uren T, et al. Hepatic precursors derived from murine embryonic stem cells contribute to regeneration of injured liver[J]. Hepatology, 2006, 44(6): 1478-1486.

[26] Miyazaki M, Hardjo M, Masaka T, et al. Isolation of a bone marrow-derived stem cell line with high proliferation potential and its application for preventing acute fatal liver failure[J].Stem Cells, 2007, 25(11): 2855-2863.

[27] Teratani T, Yamamoto H, Aoyagi K, et al. Direct hepatic fate specification from mouse embryonic stem cells[J]. Hepatology,2005, 41(4): 836-846.

[28] SullivanG J, Hay DC, Park IH, et al. Generation of functional human hepatic endoderm from human induced pluripotent stem cells[J]. Hepatology, 2010, 51(1): 329-335.

[29] Liu H, Ye Z, Kim Y, et al. Generation of endoderm derived human induced pluripotent stem cells from primary hepatocytes[J].Hepatology, 2010, 51(5): 1810-1819.

[30] Si-Tayeb K, Noto FK, Nagaoka M, et al. Highly efficient generation of human hepatocyte like cells from induced pluripoten t stem cells[J]. Hepatology, 2010, 51(1): 297-305.

[31] Chang HM, Liao YW, Chiang CH, et al. Improvement of carbon tetrachloride- induced acute hepatic failure by transplantation of induced pluripotent stem cells without reprogramming factor c-Myc[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2012, 13(3): 3598-3617.

[32] Rashid ST, Corbineau S, Hannan N, et al. Modeling inherited metabolic disorders of the liver using human induced pluripotent stem cells[J]. J Clin Invest, 2010, 120(9): 3127-3136.

[33] Alison MR, Poulsom R, Jaffery R, et al. Hepatocytes from nonhepatic adult stem cells[J]. Nature, 2000, 406(6793): 257.

[34] Korbling M, Katz RL, Khanna A, et al. Hepatocytes and epithelial cells of donor origin in recipients of peripheral blood stem cells[J]. N Engl J Med, 2002, 346(10): 738-746.

[35] Gaia S, Smedile A, Omedè P, et al. Feasibility and safety of G-CSF administration to induce bone marrow-derived cells mobilization in patients with end stage liver disease[J]. J Hepatol, 2006,45(1): 13-19.

[36] Garg V, Garg H, Khan A, et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor mobilizes CD34+cells and improves survival of patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure[J]. Gastroenterology, 2012,142(3):505-512.

[37] Levicar N, Pai M, Habib NA, et al. Long-term clinical results of autologous infusion of mobilized adult bone marrow derived CD34+ cells in patients with chronic liver disease[J]. Cell Prolif,2008, 41(Suppl1): 115-125.

[38] Salama H, Zekri AR, Zern M, et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in 48 patients with end-stage chronic liver diseases[J]. Cell Transplant, 2010, 19(11): 1475-1486.

[39] Nikeghbalian S, Pournasr B, Aghdami N, et al. Autologous transplantation of bone marrow-derived mononuclear and CD133+ cells in patients with decompensated cirrhosis[J]. Arch Iranian Med, 2011, 14(1): 12-17.

[40] Terai S, Ishikawa T, Omori K, et al. Improved liver function in patients with liver cirrhosis after autologous bone marrow cell infusion therapy[J]. Stem Cells, 2006, 24(10): 2292-2298.

[41] Lyra AC, Soares MB, da Silva LF, et al. Infusion of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells through hepatic artery results in a short-term improvement of liver function in patients with chronic liver disease: a pilot randomized controlled study[J].Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2010, 22(1): 33-42.

[42] Lyra AC, Soares MB, da Silva LF, et al. Feasibility and safety of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cell transplantation in patients with advanced chronic liver disease[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2007, 13(7): 1067-1073.

[43] Mohamadnejad M, Alimoghaddam K, Mohyeddin-Bonab M,et al. Phase I trial of autologous bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis[J]. Arch Iranian Med, 2007, 10(4): 459-466.

[44] Kim JK, Park YN, Kim JS, et al. Autologous bone marrow infusion activates the progenitor cell compartment in patients with advanced liver cirrhosis[J]. Cell Transplant, 2010, 19(10):1237-1246.

[45] Khayaziha P, Hellström PM, Noorinayer B, et al. Improvement of liver function in liver cirrhosis patients after autologous mesenchymal stem cell injection: a phase I-II clinical trial[J].Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2009, 21(10): 1199-1205.

[46] Amer ME, El-Sayed SZ, El-Kheir WA, et al. Clinical and laboratory evaluation of patients with end-stage liver cell failure injected with bone marrow-derived hepatocyte-like cells[J]. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2011, 23(10): 936-941.

[47] Peng L, Xie DY, Lin BL, et al. Autologous bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in liver failure patients caused by hepatitis B: short-term and long-term outcomes[J].Hepatology, 2011, 54(3): 820-828.

[48] Zhang Z, Lin H, Shi M, et al. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells improve liver function and ascites in decompensated liver cirrhosis patients[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2012, 27(Suppl 2): 112-120.

[49] Shi M, Zhang Z, Xu RN, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cell transfusion is safe and improves liver function in acute-onchronic liver failure patients[J]. Stem Cells Transl Med, 2012,1(10): 725-731.

[50] Wang LF, Li J, Liu HH, et al. A pilot study of umbilical cordderived mesenchymal stem cell transfusion in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2013, 28 Suppl 1: (Proof).

[51] Mohamadnejad M, Namiri M, Bagheri M, et al. Phase 1 human trial of autologous bone marrow-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with decompensated cirrhosis[J].World J Gastroenterol, 2007, 13(24): 3359-3363.

[52] Barba P, Pinana JL, Fernandez-Aviles F, et al. Pretransplantation liver function impacts on the outcome of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a study of 455 patients[J]. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant, 2011, 17(11): 1653-1661.

[53] Dinant S, Vetelainen RL, Florquin S, et al. IL-10 attenuates hepatic I/R injury and promotes hepatocyte proliferation[J]. J Surg Res, 2007, 141(2): 176-182.

[54] Cai J, Zhang X, Wang X, et al. In vivo MR imaging of magnetically labeled mesenchymal stem cells transplanted into rat liver through hepatic arterial injection[J]. Contrast Media Mol Imaging, 2008, 3(2): 61-66.

[55] Modo M, Meade TJ, Mitry RR. Liver cell labeling with MRI contrast agents[J].MethodsMol Biol, 2009, 481: 207-219.

[56] Honczarenko M, Le Y, Swierkowski M, et al. Human bone marrow stromal cells express a distinct set of biologically functional chemokine receptors[J]. Stem Cells, 2006, 24(4):1030-1041.

[57] Wang X, Montini E, Al-Dhalimy M, et al. Kinetics of liver repopulation after bone marrow transplantation[J]. Am J Pathol,2002, 161(2): 565-574.

[58] Kollet O, Shivtiel S, Chen YQ, et al. HGF, SDF-1, and MMP-9 are recruitment to the liver[J]. J Clin Invest, 2003, 112(2): 160-169.

[59] Kitaori T, Ito H, Schwarz EM, et al. Stromal cell-derived factor 1/CXCR4 signaling is critical for the recruitment of mesenchymal stem cells to the fracture site during skeletal repair in a mouse model[J]. Arthritis Rheum, 2009, 60(3): 813-823.

[60] Son BR, Marquez-Curtis LA, KuciaM, et al. Migration of bone marrow and cord blood mesenchymal stem cells in vitro is regulated by stromal-derived factor-1-CXCR4 and hepatocyte growth factor-c-met axes and involves matrix metalloproteinases[J]. Stem Cells, 2006, 24(5): 1254-1264.

[61] Lapidot T, Dar A, Kollet O. How do stem cells find their way home[J]? Blood, 2005, 106(6): 1901-1910.

[62] Li CY, Kong YX, Wang H, et al. Homing of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells mediated by sphingosine 1-phosphate contributes to liver fibrosis[J]. J Hepatol, 2009, 50(6): 1174-1183.

[63] Schwartz RE, Reyes M, Koodie L, et al. Multipotent adult progenitor cells from bone marrow differentiate into functional hepatocyte-like cells[J]. J Clin Invest, 2002, 109(10): 1291-1302.

[64] Okuyama H, Krishnamachary B, Zhou YF, et al. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 in bone marrowderived mesenchymal cells is dependent on hypoxia-inducible factor[J]. J Biol Chem, 2006, 281(22): 15554-15563.

[65] Aurich H, Sgodda M, Kaltwasser P, et al. Hepatocyte differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells from human adipose tissue in vitro promotes hepatic integration in vivo[J]. Gut, 2009,58 (4): 570-581.

[66] Campard D, Lysy PA, NajimiM, et al. Native umbilical cord matrix stem cells express hepatic markers and differentiate into hepatocyte-like cells[J]. Gastroenterology, 2008, 134(3): 833-848.

[67] Kohler C, BellA W, Bowen WC, et al. Expression of Notch-1 and its ligand Jagged-1 in rat liver during liver regeneration[J].Hepatology, 2004, 39(4): 1056-1065.

[68] Shafritz DA, Oertel M, Menthena A, et al. Liver stem cells and prospects for liver reconstitution by transplanted cells[J].Hepatology, 2006, 43 (2 Suppl 1): S89-S98.

[69] Moore KA, Lemischka IR. Stem cells and their niches[J].Science, 2006, 311(5769): 1880-1885.

[70] Phinney DG, Prockop DJ. Concise review: mesenchymal stem/multipotent st romal cells: the state of transdifferentiation and modes of tissue repair-current views[J]. Stem Cells, 2007,25(11): 2896-2902.

[71] Parekkadan B, van Poll D, Suganuma K, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived molecules reverse fulminant hepatic failure[J]. PLos One, 2007, 2(9): e941.

[72] van Poll D, Parekkadan B, Cho CH, et al. Mesenchymal stem cellderived molecules directly modulate hepatocellular death and regeneration in vitro and in vivo[J]. Hepatology, 2008, 47(5):1634-1643.

[73] Nakamura T, Torimura T, Sakamoto M, et al. Significance and therapeutic potential of endothelial progenitor cell transplantation in a cirrhotic liver rat model[J].Gastroenterology, 2007, 133(1): 91-107.

[74] Taniguchi E, Kin M, Torimura T, et al. Endothelial progenitor cell transplantation improves the survival following liver injury in mice[J]. Gastroenterology, 2006, 130(2): 521-531.

[75] Bonzo LV, Ferrero I, Cravanzola C, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells as a two-edged sword in hepatic regenerative medicine: engraftment and hepatocyte differentiation versus profibrogenic potential[J]. Gut, 2008, 57(2): 223-231.