间充质干细胞定向分化及其在肝脏疾病应用中的启示

2013-07-12王汉裕刘拥军

王汉裕 刘拥军

•述 评•

间充质干细胞定向分化及其在肝脏疾病应用中的启示

王汉裕 刘拥军★

间充质干细胞向肝细胞诱导分化成功后,分化后的肝细胞样细胞应用于肝病成为了研究热点。不仅未分化的间充质干细胞能治疗肝病,其来源的分化后的肝细胞样细胞亦能有效治疗肝病。因此,有必要对间充质干细胞分化前后的细胞治疗效果进行比较评价。本文从诱导分化培养方案、鉴定指标及相关细胞生物学功能进行述评。

间充质干细胞;定向分化;细胞治疗;肝病

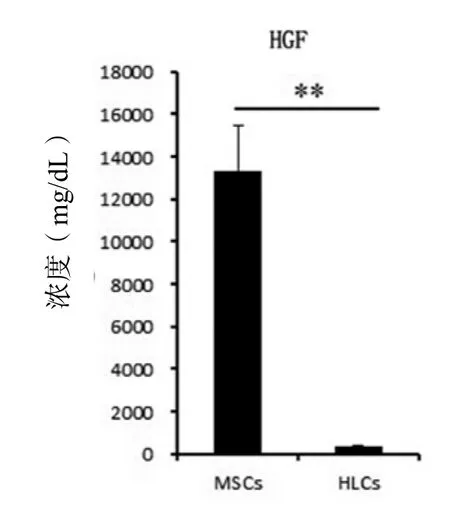

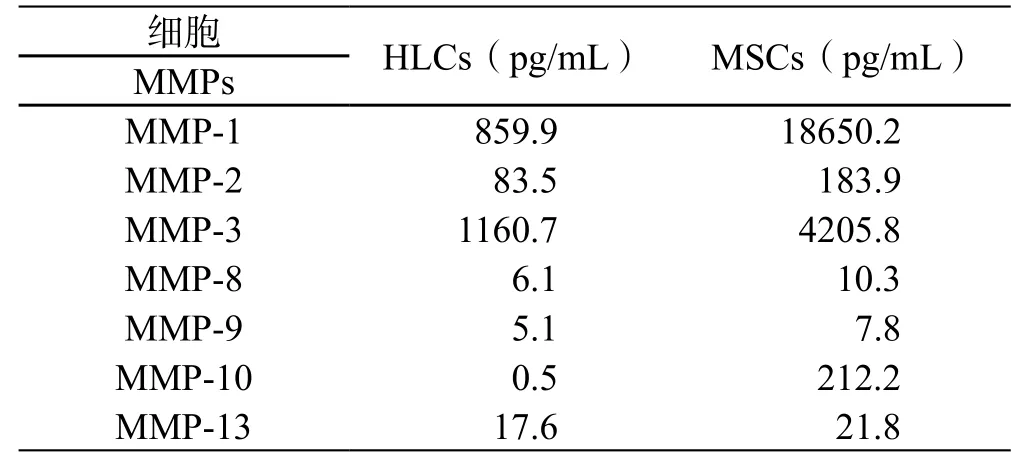

干细胞研究的发展促进了应用干细胞治疗肝病的研究,丰富了肝病的治疗手段,尤其是肝硬化及肝功能衰竭的治疗。基于干细胞的分化潜能,利用干细胞,尤其是间充质干细胞(mesenchymal stem cells,MSCs),向肝细胞进行诱导分化培养,可获得肝细胞样细胞(hepatocyte-like cells,HLCs),并应用于肝病的治疗。不少研究开始比较MSCs向肝细胞分化前后用于肝病治疗。我们发现MSCs经过向肝细胞分化诱导培养后,丢失了高分泌基质金属蛋白酶(matrix metalloproteinases,MMPs)和肝细胞生长因子(hepatocyte growth factor,HGF)的能力。我们及其他实验均发现分化后的HLCs治疗肝病的效果不如未分化的MSCs。本文结合本实验的研究,综合目前相关研究文献,对MSCs向肝细胞定向分化及其在肝病中的应用进行简要述评。

1 分化诱导培养方案的选择依据

2001年小鼠胚胎干细胞(embryonic stem cells,ESCs)[1]和2002年多潜能成体祖细胞(multipotent adult progenitor cells,MAPCs)[2]在体外向HLCs诱导分化培养获得成功后,2004年MSCs在体外向HLCs分化诱导培养也获得成功[3]。小鼠ESCs向HLCs的诱导分化方案中,ESCs在不含白血病抑制因子(leukemia inhibitory factor,LIF)的培养基中培养5天,继而接种于I型胶原包被的培养皿中培养4天(基础培养基为含20% 胎牛血清和300μM硫代甘油的IMDM,依次添加酸性成纤维细胞生长因子(acidic fibroblast growth factor,aFGF,100 ng/mL)、HGF(20 ng/mL);在诱导培养的第15天,添加抑瘤素M(oncostatin M,OSM,10 ng/mL)、地塞米松(dexamethasone,DXM,10-7M)、ITS混合物(5 mg/mL胰岛素、5 mg/mL转铁蛋白、5μm/mL亚硒酸)培养3天。经过18天的诱导分化培养,ESCs成功分化为具有部分肝细胞功能的HLCs。基于ESCs和MAPCs的诱导方案,改进的MSCs诱导方案采用了两步法,首先用含肝HGF(20 ng/mL)、碱性成纤维细胞生长因子(basic fi broblast growth factor,bFGF,10 ng/mL)和尼克酰胺(0.61 g/L)的IMDM培养基培养1周;更换为诱导成熟培养基,即含OSM(20 ng/mL)、地塞米松(1×10-6mol/L)和 ITS 混合物(25 g/L胰岛素、25 g/L转铁蛋白、25 mg/L亚硒酸钠)的IMDM,继续培养3周。经过4周的诱导分化培养,细胞形态从梭型转变为典型的肝细胞样椭圆形,并能检测到细胞色素P450(cytochrome P450,CYP)的2B6(CYP 2B6)亚型。随后文献中出现的培养分化方案都在此方案上加于变化,比如预先在I型[4]或IV型胶原[5]包被的培养皿上培养2天,再继续往下分化培养;把MSCs接种在Matrigel包被的纳米聚酰胺纤维上进行分化培养[6]。

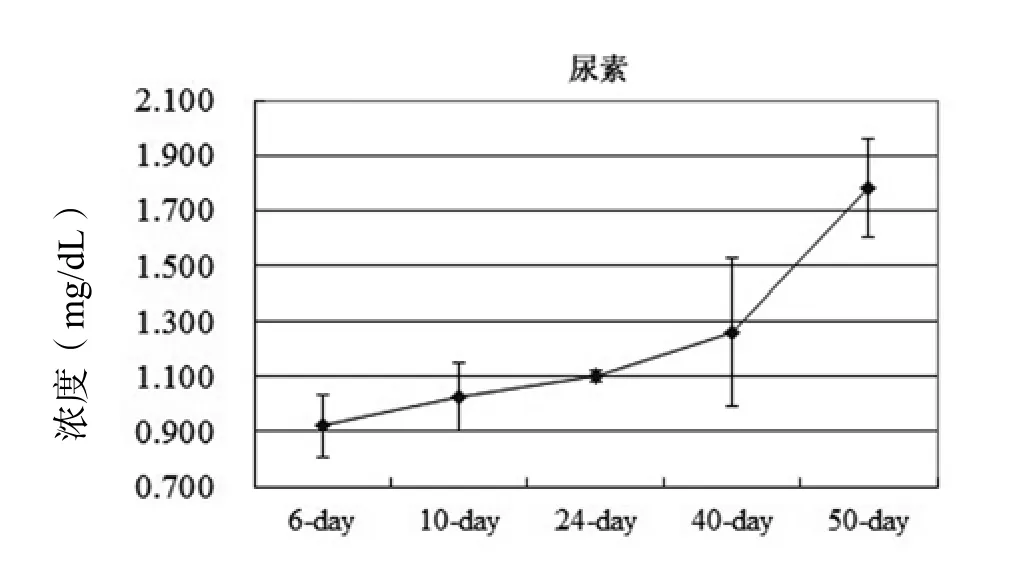

在干细胞向HLCs分化培养过程中,除了HGF外,目前的分化培养方案中均需要添加bFGF[1~5]。我们简化了上述的分化方案,MSCs向HLCs分化诱导培养依然获得成功。我们的诱导方案也是采取两步法,在第一阶段采用10-8mol/L的地塞米松、50 ng/mL的HGF、10 ng/mL的表皮生长因子(epidermal growth factor,EGF)、1% ITS的DMEM-F12(高糖)培养基诱导培养2周;第二阶段,使用含2%的FBS、20 ng/mL的OSM、10-6mol/L的DXM、1% ITS的DMEM-F12培养基诱导培养4周。考虑到第二阶段的培养时间延长,添加低浓度的FBS以维持细胞的活性。经过6周的诱导培养后,细胞逐渐变成圆形(图1),并具有成熟肝细胞的功能,比如合成糖元(图2)、分泌尿素(图3)等。这说明MSCs向HLCs分化的过程中,bFGF不是必需的。bFGF是胚胎干细胞培养基中维持ESCs未分化状态的一个重要组成因子[7]。最近也有研究发现bFGF联合骨形态发生蛋白4(bone morphogenetic protein-4,BMP-4)促进了ESCs向成骨细胞和成软骨细胞分化[8]。

图1 诱导分化前后的细胞形态Figure 1 Cells morphology changes after hepatic differentiation

图2 糖原染色(PAS法)Figure 2 Glycogen detection by PAS staining

图3 随着诱导分化培养时间的延长,尿素分泌逐渐增多Figure 3 The differentiated cells synthesized urea in a timedependent manner

2 分化诱导的鉴定标记及其意义

不管大鼠[9]、小鼠[10],还是人类[3],各种来源的(骨髓[11]、脐带、脐带血[12]或脂肪[11,13,14])MSCs均能分化为HLCs,为将来肝病的细胞治疗解决了细胞来源的技术难题。但是,目前没有提出一个特异的指标来明确干细胞向HLCs分化成功与否,也没有明确的鉴定指标来评价分化效率。因此,在相关文献中,均采用多指标评价系统。常用的鉴定标记有白蛋白(albumin)、甲胎蛋白(α-fetoprotein,AFP)、细胞角蛋白(cytokeratine,CK)、肝细胞核因子(hepatocyte nuclear factor,HNF)、细胞色素(cytochrome,CYP)P450、酪氨酸转氨酶(tyrosine-aminotransferase)、色氨酸2,3双加氧酶(tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase)等,体现具有肝细胞功能的鉴定方法有过碘酸-希夫(Periodic Acid-Schiff,PAS)染色、Dil-Ac-LDL吸收、尿素合成等。另外,部分上述指标还存在亚型,比如细胞角蛋白包括CK7[6]、CK18[5]、CK19[2],HNF包括HNF-1α[2]、HNF-3β[2]、HNF-4α[5]。然而,尚未有某一篇文献全部采用上述指标。有研究发现诱导分化早期出现的指标有HNF-3β、CK19、AFP,而CK18、albumin、HNF-1α、CYP则表达于诱导分化晚期[2]。经过4周的诱导,HLCs表达 CYP 2B6,而肝细胞核因子4(HNF-4)在诱导6周后才表达[3]。

不少文献提到MSC在诱导分化之前没有表达ALB、AFP、CK18[5,15,16]、CK19[15]。亦有文献报道,经过诱导分化培养后的细胞只有70%表达白蛋白[5]。BM-MSCs低表达白蛋白、CK18、色氨酸2,3双加氧酶,但不表达 AFP[3]。但是,我们发现未经过诱导分化的UC-MSCs本身高表达白蛋白、CK19和AFP(图4)。这些数据证明了白蛋白、色氨酸2,3双加氧酶、CK18、CK19和AFP不能作为骨髓和脐带来源的MSCs在向肝细胞诱导分化的鉴定指标。分泌尿素是肝细胞活性的一个特性,但是肾小管上皮细胞也分泌尿素。CYP虽然首先在肝细胞中发现,但也在其他细胞中表达[18]。即使是肝细胞相对特异性指标的CYP,其不同亚型的活性亦存在种属特异性,如大鼠的CYP 2B1[19]、小鼠的CYP 2B9和CYP 2B13[20,21]、人的CYP 2B6[2]。尽管肝细胞具有LDL吸收的功能,但其他细胞也有这样的特性[22]。综合目前的文献报道,只有肝细胞能合成和存储糖原[2]。在包被了Matrigel上培养的MAPCs分化为HLCs(同时表达白蛋白、CK18、HNF-3β)的分化率能达到 91%[2]。经过6周的诱导,大约 50%的分化细胞具有存储糖原的功能[3]。

3 诱导前后的细胞生物学相关研究

自从建立了干细胞向HLCs分化诱导的成熟方案,不少研究者随即对这些HLCs生物学功能和特性进行深入的研究。由于ESCs具有高度的致瘤性,在体外进行诱导分化时,很容易混杂未能充分分化的ESCs[23,24],这就给临床使用带来高风险,限制其临床应用。和ESCs相比,成体干细胞不具有明显潜在的成瘤性,没有伦理问题的困扰,非常适合于临床的应用[25]。

图4 免疫荧光方法检测间充质干细胞表达的白蛋白、细胞角蛋白19、甲胎蛋白Figure 4 Expressions of albumin, CK19 and AFP from MSCs by immuno fl uorescence microscopy

MSCs向HLCs诱导分化的培养方案已经得到很好的建立[3]。分化后的HLCs具有向损伤肝脏部位迁移的能力,而且能在体内分泌白蛋白[26~28]。人脂肪来源的MSCs诱导分化为HLCs后,能减轻四氯化碳对裸鼠造成的急性肝损伤程度[29]。这些结果说明来源于干细胞的HLCs合适于治疗肝病,尤其是急性肝衰竭和终末期肝病[30]。分化后的HLCs和未经分化诱导的MSC均有报道其对肝病的治疗作用,例如肝纤维化[31~33]、肝损伤[34,35]、爆发性肝衰竭[27,29,36]和肝再生[26,37,38]。由于MSCs向肝细胞分化前后,对肝病的治疗均有效果,因此,需要对分化前后的细胞进行功能相关比较研究。

动物实验证明,MSCs不仅能迁移到损伤的部位,修复损伤的组织,并使损伤的组织恢复一定的功能[27,39,40];而且能减少细胞的死亡,并促进内源性再生[41,42]。另外,MSCs也易于体外培养扩增。这些特性使得MSCs成为临床细胞治疗的最佳来源。MSCs修复组织的可能机制在于分泌可溶性细胞因子,这些细胞因子能抑制炎症和免疫反应,也能刺激内源性干细胞的增殖和分化,从而起到组织修复作用[43,44]。体内实验证明未分化的MSCs比分化后的HLCs治疗急性肝衰竭的效果更好[27],我们的数据也证明了这点。由于未分化的MSCs亦表达高水平的白蛋白,这有益于肝病的治疗。这也说明前期动物实验发现HLCs在肝脏分泌白蛋白的数据是值得商榷的。需要注意的是,发现MSCs输入治疗后有向肝细胞分化的实验研究中,均采用的是免疫缺陷小鼠[15,26],而MSCs在免疫系统正常小鼠体内存留时间大概为23天[45]。在不同的动物模型中,MSCs能改善肝脏功能,而没有出现细胞融合[27,46]。

HGF是促进肝细胞增殖[47,48]和肝再生[47,49]的最强效细胞因子。HGF刺激肝干/祖细胞的增殖来修复肝损伤[50]。HGF可引起Bcl-xL的强烈表达,阻断Fas及其配体激活后的信号传导,抑制Fas介导的肝细胞凋亡[51],从而治疗Fas引起的爆发性肝衰竭[52]。HGF除了能诱导肝实质细胞的迅速增殖外,还能刺激胆管上皮细胞增殖,因而影响整个器官的发育。由于HGF有促进肝细胞增殖和抑制凋亡的特性,使得HGF可能是肝病细胞治疗的一个关键因子。我们和其他的研究小组都发现MSCs分泌高水平的HGF[53]。而且,脐带来源的MSCs分泌HGF的量比骨髓来源的MSCs高30倍[53]。 除了HGF,MSCs也分泌高水平的MMPs,这些分泌的MMPs有利于组织修复和肝纤维化的治疗。MSCs分化为HLCs后,其分泌的HGF(图5)和MMPs(表1)都显著降低。也有数据证明MSCs向HLCs分化培养结束后,并不是处于分化终末期的稳定状态,这增加了成瘤性的风险[54]。

图5 细胞分化前后肝细胞生长因子的表达水平变化Figure 5 The change of hepatocyte growth factor expression after hepatic differentiation

表1 细胞分化前后基质金属蛋白酶的分泌水平变化Table 1 Matrix metalloproteinase changes after hepatic differentiation

综上所述,由于没有明确的鉴定标准,也难于评价分化效率。MSCs分化为HLCs后,丢失了分泌HGF和MMPs的能力,而HGF和MMPs均有利于相关肝病的治疗。这些数据说明直接用未分化的MSCs治疗肝病效果好于经过诱导分化培养后的细胞,而且还节约培养成本。

[1] Hamazaki T, Iiboshi Y, Oka M, et al. Hepatic maturation in differentiating embryonic stem cells in vitro[J]. FEBS Lett, 2001, 497(1): 15-19.

[2] Schwartz R E, Reyes M, Koodie L, et al. Multipotent adult progenitor cells from bone marrow differentiate into functional hepatocyte-like cells[J]. J Clin Invest, 2002,109(10): 1291-1302.

[3] Lee K D, Kuo T K, Whang-Peng J, et al. In vitro hepatic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells[J]. Hepatology, 2004, 40(6): 1275-1284.

[4] Lue J, Lin G, Ning H, et al. Transdifferentiation of adiposederived stem cells into hepatocytes: a new approach[J]. Liver Int, 2010, 30(6): 913-922.

[5] Sa-ngiamsuntorn K, Wongkajornsilp A, Kasetsinsombat K, et al. Upregulation of CYP 450s expression of immortalized hepatocyte-like cells derived from mesenchymal stem cells by enzyme inducers[J]. BMC Biotechnol, 2011, 11: 89.

[6] Piryaei A, Valojerdi M R, Shahsavani M, et al. Differentiation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells into hepatocyte-like cells on nano fi bers and their transplantation into a carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis model[J]. Stem Cell Rev, 2011, 7(1): 103-118.

[7] Liu Y, Song Z, Zhao Y, et al. A novel chemical-defined medium with bFGF and N2B27 supplements supports undifferentiated growth in human embryonic stem cells[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2006, 346(1): 131-139.

[8] Lee T J, Jang J, Kang S, et al. Enhancement of osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation of human embryonic stem cells by mesodermal lineage induction with BMP-4 and FGF2 treatment[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2013, 430(2): 793-797.

[9] Lange C, Bassler P, Lioznov M V, et al. Hepatocytic gene expression in cultured rat mesenchymal stem cells[J]. Transplant Proc, 2005, 37(1): 276-279.

[10] Wang P P, Wang J H, Yan Z P, et al. Expression of hepatocyte-like phenotypes in bone marrow stromal cells after HGF induction[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2004, 320(3): 712-716.

[11] Taléns-Visconti R, Bonora A, Jover R, et al. Hepatogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells from adipose tissue in comparison with bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2006, 12(36): 5834-5845.

[12] Hong S H, Gang E J, Jeong J A, et al. In vitro differentiation of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells into hepatocyte-like cells[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2005, 330(4): 1153-1161.

[13] Seo M J, Suh S Y, Bae Y C, et al. Differentiation of human adipose stromal cells into hepatic lineage in vitro and in vivo[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2005, 328(1): 258-264.

[14] Banas A, Teratani T, Yamamoto Y, et al. Adipose tissuederived mesenchymal stem cells as a source of human hepatocytes[J]. Hepatology, 2007, 46(1): 219-228.

[15] Yu J, Cao H, Yang J, et al. In vivo hepatic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells from human umbilical cord blood after transplantation into mice with liver injury[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2012, 422(4): 539-545.

[16] Hwang S, Hong H N, Kim H S, et al. Hepatogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells in a rat model of thioacetamide-induced liver cirrhosis[J]. Cell Biol Int, 2012, 36(3): 279-288.

[17] Dunn J C, Tompkins R G, Yarmush M L. Long-term in vitro function of adult hepatocytes in a collagen sandwich con fi guration[J]. Biotechnol Prog, 1991, 7(3): 237-245.

[18] Hedlund E, Gustafsson J A , Warner M. Cytochrome P450 in the brain; a review[J]. Curr Drug Metab, 2001, 2(3): 245-263.

[19] Tzanakakis E S, Hsiao C C, Matsushita T, et al. Probing enhanced cytochrome P450 2B1/2 activity in rat hepatocyte spheroids through confocal laser scanning microscopy[J]. Cell Transplant, 2001, 10(3): 329-342.

[20] Li-Masters T, Morgan E T. Effects of bacterial lipopolysaccharide on phenobarbital-induced CYP2B expression in mice[J]. Drug Metab Dispos, 2001, 29(3): 252-257.

[21] Jarukamjorn K, Sakuma T, Miyaura J, et al. Different regulation of the expression of mouse hepatic cytochrome P450 2B enzymes by glucocorticoid and phenobarbital[J]. Arch Biochem Biophys, 1999, 369(1): 89-99.

[22] Rader D J, Dugi K A. The endothelium and lipoproteins: insights from recent cell biology and animal studies[J]. Semin Thromb Hemost, 2000, 26(5): 521-528.

[23] Basma H, Soto-Gutiérrez A, Yannam G R, et al. Differentiation and transplantation of human embryonic stem cell-derived hepatocytes[J]. Gastroenterology, 2009, 136(3): 990-999.

[24] Kroon E, Martinson L A, Kadoya K, et al. Pancreatic endoderm derived from human embryonic stem cells generates glucose-responsive insulin-secreting cells invivo[J]. Nat Biotechnol, 2008, 26(4): 443-452.

[25] Werbowetski-Ogilvie T E, Bossé M, Stewart M, et al. Characterization of human embryonic stem cells with features of neoplastic progression[J]. Nat Biotechnol, 2009, 27(1): 91-97.

[26] Aurich H, Sgodda M, Kaltwasser P, et al. Hepatocyte differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells from human adipose tissue in vitro promotes hepatic integration in vivo[J]. Gut, 2009, 58(4): 570-581.

[27] Kuo T K, Hung S P, Chuang C H, et al. Stem cell therapy for liver disease: parameters governing the success of using bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells[J]. Gastroenterology, 2008, 134(7): 2111-2121, 2121. e1-e3.

[28] Aurich I, Mueller L P, Aurich H, et al. Functional integration of hepatocytes derived from human mesenchymal stem cells into mouse livers[J]. Gut, 2007, 56(3): 405-415.

[29] Banas A, Teratani T, Yamamoto Y, et al. Rapid hepatic fate specification of adipose-derived stem cells and their therapeutic potential for liver failure[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2009, 24(1): 70-77.

[30] Muraca M. Cell therapy as support or alternative to liver transplantation[J]. Transplant Proc, 2003, 35(3): 1047-1048.

[31] Zhang D, Jiang M, Miao D. Transplanted human amniotic membrane-derived mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate carbon tetrachloride-induced liver cirrhosis in mouse[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(2): e16789.

[32] Lin S Z, Chang Y J, Liu J W, et al. Transplantation of human Wharton's Jelly-derived stem cells alleviates chemically induced liver fibrosis in rats[J]. Cell Transplant, 2010, 19(11): 1451-1463.

[33] Tsai P C, Fu T W, Chen Y M, et al. The therapeutic potential of human umbilical mesenchymal stem cells from Wharton's jelly in the treatment of rat liver fibrosis[J]. Liver Transpl, 2009, 15(5): 484-495.

[34] Stock P, Brückner S, Ebensing S, et al. The generation of hepatocytes from mesenchymal stem cells and engraftment into murine liver[J]. Nat Protoc, 2010, 5(4): 617-627.

[35] Banas A, Teratani T, Yamamoto Y, et al. IFATS collection: in vivo therapeutic potential of human adipose tissue mesenchymal stem cells after transplantation into mice with liver injury[J]. Stem Cells, 2008, 26(10): 2705-2712.

[36] Parekkadan B, van Poll D, Suganuma K, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived molecules reverse fulminant hepatic failure[J]. PLoS One, 2007, 2(9): e941.

[37] Lam S P, Luk J M, Man K, et al. Activation of interleukin-6-induced glycoprotein 130/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 pathway in mesenchymal stem cells enhances hepatic differentiation, proliferation, and liver regeneration[J]. Liver Transpl, 2010, 16(10): 1195-1206.

[38] van Poll D, Parekkadan B, Cho C H, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived molecules directly modulate hepatocellular death and regeneration in vitro and in vivo[J]. Hepatology, 2008, 47(5): 1634-1643.

[39] Tögel F, Hu Z, Weiss K, et al. Administered mesenchymal stem cells protect against ischemic acute renal failure through differentiation-independent mechanisms[J]. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol, 2005, 289(1): F31-F42.

[40] Sato Y, Araki H, Kato J, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells xenografted directly to rat liver are differentiated into human hepatocytes without fusion[J]. Blood, 2005, 106(2): 756-763.

[41] Miyahara Y, Nagaya N, Kataoka M, et al. Monolayered mesenchymal stem cells repair scarred myocardium after myocardial infarction[J]. Nat Med, 2006, 12(4): 459-465.

[42] Gnecchi M, He H, Liang O D, et al. Paracrine action accounts for marked protection of ischemic heart by Aktmodi fi ed mesenchymal stem cells[J]. Nat Med, 2005, 11(4): 367-368.

[43] Watanabe M, Murata S, Hashimoto I, et al. Platelets contribute to the reduction of liver fibrosis in mice[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2009, 24(1): 78-89.

[44] Munoz J R, Stoutenger B R, Robinson A P, et al. Human stem/progenitor cells from bone marrow promote neurogenesis of endogenous neural stem cells in the hippocampus of mice[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2005, 102(50): 18171-18176.

[45] Zangi L, Margalit R, Reich-Zeliger S, et al. Direct imaging of immune rejection and memory induction by allogeneic mesenchymal stromal cells[J]. Stem Cells, 2009, 27(11): 2865-2874.

[46] Kaibori M, Adachi Y, Shimo T, et al. Stimulation of liver regeneration after hepatectomy in mice by injection of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells via the portal vein[J]. Transplant Proc, 2012, 44(4): 1107-1109.

[47] Ishii T, Sato M, Sudo K, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor stimulates liver regeneration and elevates blood protein level in normal and partially hepatectomized rats[J]. J Biochem, 1995, 117(5): 1105-1112.

[48] Fujiwara K, Nagoshi S, Ohno A, et al. Stimulation of liver growth by exogenous human hepatocyte growth factor in normal and partially hepatectomized rats[J]. Hepatology, 1993, 18(6): 1443-1449.

[49] Matsumoto K, Nakamura T. Hepatocyte growth factor: molecular structure and implications for a central role in liver regeneration[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 1991, 6(5): 509-519.

[50] Hasuike S, Ido A, Uto H, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor accelerates the proliferation of hepatic oval cells and possibly promotes the differentiation in a 2-acetylaminofluorene/ partial hepatectomy model in rats[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2005, 20(11): 1753-1761.

[51] Suzuki H, Toyoda M, Horiguchi N, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor protects against Fas-mediated liver apoptosis in transgenic mice[J]. Liver Int, 2009, 29(10): 1562-1568.

[52] Kosai K, Matsumoto K, Nagata S, et al. Abrogation of Fasinduced fulminant hepatic failure in mice by hepatocyte growth factor[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 1998, 244(3): 683-690.

[53] Friedman R, Betancur M, Boissel L, et al. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells: adjuvants for human cell transplantation[J]. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant, 2007, 13(12): 1477-1486.

[54] Le Blanc K, Tammik C, Rosendahl K, et al. HLA expression and immunologic properties of differentiated and undifferentiated mesenchymal stem cells[J]. Exp Hematol, 2003, 31(10): 890-896.

Mesenchymal stem cells committed differentiation and its application in liver diseases therapy

WANG Hanyu, LIU Yongjun★

(Alliancells Institute of Stem Cells and Translational Regenerative Medicine, Tianjin 300300, China)

The protocols for differentiation of hepatocyte-like cells (HLCs) from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been well established. Previous datas have shown that MSCs and their derived-HLCs were able to engraft injured liver and alleviate injuries. It is necessary to elvaluate the cells therapeutic effects before and after MSCs differentiation. We will make a brief comment on the induction and differentiation culture protocol, hepatic markers and related functions of cell biology.

Mesenchymal stem cells; Committed differentiation; Cytotherapy; Liver diseases

国家自然科学基金(30872618)

和泽干细胞转化再生医学研究中心,天津 300300

★通讯作者:刘拥军,E-mail: andyliuliu2001@yahoo.com.cn