Borderline resectable pancreatic tumors: Is there a need for further re fi nement of this stage?

2011-12-14ShaileshShrikhandeSupreetaAryaSavioGeorgeBarretoSachinIngleMelroySouzaRohiniHawaldarandParulShukla

Shailesh V Shrikhande, Supreeta Arya, Savio George Barreto, Sachin Ingle,Melroy A D'Souza, Rohini Hawaldar and Parul J Shukla

Mumbai, India

Borderline resectable pancreatic tumors: Is there a need for further re fi nement of this stage?

Shailesh V Shrikhande, Supreeta Arya, Savio George Barreto, Sachin Ingle,Melroy A D'Souza, Rohini Hawaldar and Parul J Shukla

Mumbai, India

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2011; 10: 319-324)

pancreatic head carcinoma;pancreatic cancer;pancreatic neoplasms;resection

Introduction

The best treatment option for nearly all pancreatic tumors is a surgical resection. However, major pancreatic resections are a challenging undertaking fraught with considerable morbidity and even mortality.[1]Traditionally, pancreatic cancer has been classi fi ed based on preoperative imaging and intraoperative surgical fi ndings into resectable, locally advanced, and metastatic disease.[2]However, more recently, another entity, borderline resectable pancreatic tumor (BRT),has been proposed and its de fi nition continues to evolve.[3-6]The National Comprehensive Cancer Network(NCCN) describes borderline resectable pancreatic head(and body) cancer as tumor abutment to the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), severe unilateral superior mesenteric vein (SMV) or portal vein (PV) impingement,gastroduodenal artery (GDA) encasement up to its origin from the hepatic artery, or colon and mesocolon invasion.[3]Despite these published or recommended criteria, a number of situations fall in the "grey zone"between resectability and borderline resectability. The ideal treatment of patients with BRTs needs to be established. While some surgeons advise neoadjuvant chemo(radio)therapy in all these patients,[6]others suggest that surgery may be offered at the fi rst instance if the achievement of a complete resection is deemed possible at preoperative staging.[7]This grey zone includesthose situations where vascular resections are anticipated(or tumors are classi fi ed as borderline pre-operatively)but not ultimately required and yet an R0 resection is achieved.[4]Since the ultimate aim of the pancreatic surgeon is to ensure an R0 resection for all pancreatic tumors (and not just pancreatic adenocarcinoma), we sought to identify speci fi c fi ndings on preoperative imaging that could help predict in which BRTs a complete resection, with or without vascular resections(VRs), could be achieved, based on a retrospective analysis of a prospectively maintained database of patients with a heterogenous group of BRTs (i.e. ductal adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumors and solid pseudopapillary tumors) of the pancreas.

Methods

Data were retrospectively analyzed from a prospectively maintained database of the Gastrointestinal and HPB Service of the Tata Memorial Hospital from 2003 to 2008. In 180 patients who had undergone pancreatic resections in this period, 12 were identi fi ed to have had BRT, as per the de fi nition provided by the NCCN.[3]

Image acquisition

While 7 of the 12 patients had imaging performed at our institution, 5 had imaging studies performed elsewhere. However, all the images were reviewed by a single consultant radiologist (Arya S).

In the 7 patients who had their preoperative imaging at our institution, contrast-enhanced computed tomography(CT) was performed on a 16-slice multidetector CT(MDCT) scanner (Light speed 16; General Electric).

Non-enhanced and biphasic contrast-enhanced CT was performed after injecting 100 mL of non-iodinated contrast (320 mgI/mL) at 3 mL/sec using a power injector. Water was used as the oral contrast agent, 750 mL 30 minutes before the study and another 250 mL immediately before the study. Images were acquired both in the pancreatic parenchymal phase (35 seconds after injection) and portal venous phase (65 seconds after injection). Slice collimation was 1.25 mm and reconstruction was done both at 1.25 and 5 mm.

The studies performed elsewhere were considered acceptable if a biphasic contrast-enhanced CT study was available and DICOM data were present. All these studies had been performed on a 16-slice or 64-slice MDCT scanner.

Image interpretation

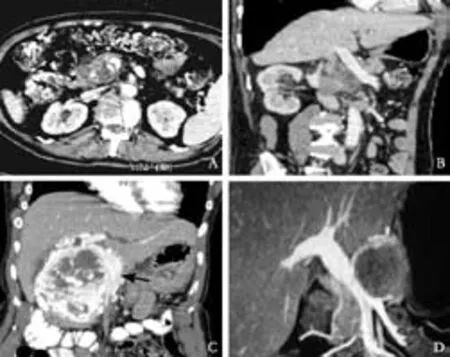

Image analysis and interpretation were done using axial images as well as multiplanar reconstructions on the General Electric PACS system. Curved planar reformations and volume rendering were also used where deemed necessary for studying the relationship of the tumor to peripancreatic vessels.

The parameters evaluated were the tumor location,size, and its relation with the relevant peripancreatic vessels. For the tumors of the head and neck, the relation with the PV, SMV, SMA, celiac artery and hepatic artery were evaluated. In pancreatic neck and body tumors, the relation with the splenic artery and splenic vein was also evaluated.

Tumor relationship with the PV, SMV and SMA was assessed using two parameters. The fi rst required measurement was of the maximum degree of circumferential contact of the tumor with the vessel(CC). This measurement was obtained using the angle measurement tool available on the PACS. The angle(criteria for maximum degree of circumferential contact)obtained was classi fi ed as follows: grade 0, no contact of the tumor with the vessel; grade I, tumor to vessel contact<90°; grade II, tumor to vessel contact ≥90° and <180°;grade III, tumor to vessel contact ≥180° but <270°; grade IV, tumor to vessel contact ≥270°.

The second parameter was the length of contact of the tumor with the vessel (LC). This was measured both on the coronal/sagittal reformations and the axial images.

A third parameter was also recorded and mainly used for the SMV but also the PV. The degree of luminal narrowing of the vessel at the point of contact with the tumor (venous deformity, VD) was also measured. The minimum luminal diameter of the vein in contact with the tumor was the numerator and the denominator was the diameter of the vein immediately proximal and not in contact with the tumor. The criteria for VD are outlined below: grade 0, no luminal narrowing; grade 1,<50% narrowing; grade 2, ≥50% narrowing.

The tumor relationships with adjacent organs and structures were also recorded. Image analysis and recording also included the presence or absence of hepatic metastases, ascites, peritoneal nodules and adenopathy.

The operations performed included pyloruspreserving pancreatoduodenectomy (PPPD), classical Whipple's resection, subtotal pancreatectomy and total pancreatectomy (TP) with or without vascular resections. Certain crucial steps or maneuvers (i.e.dissection around the SMV or PV and splenic vein and also dissection of the common hepatic artery and GDA)were common to all the above resection procedures irrespective of the tumor pathology.

The decision to perform a venous resection was made intra-operatively. Clear venous involvement was easy to judge, and in other situations an attempt was made to develop an avascular plane between the pancreas or tumor and the vein (usually an edematous plane). If this initial trial was considered encouraging enough, dissection was continued further and vein salvage achieved. Intraoperative discovery of arterial involvement resulted in a decision to settle for R1 or R2 resection depending on the speci fi c intra-operative situation.

The vascular resections were either vein resections with interposition grafts (i.e. polytetra fl uoroethylene(PTFE) grafts) or resections with primary anastomosis.

Post-operative complications were de fi ned as in our previous publications and the de fi nitions proposed by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery.[1,8-12]

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Product and Service Solutions, SPSS 14.0 for Windows. Nominal data are expressed as number (%)and continuous data as median (range).

Results

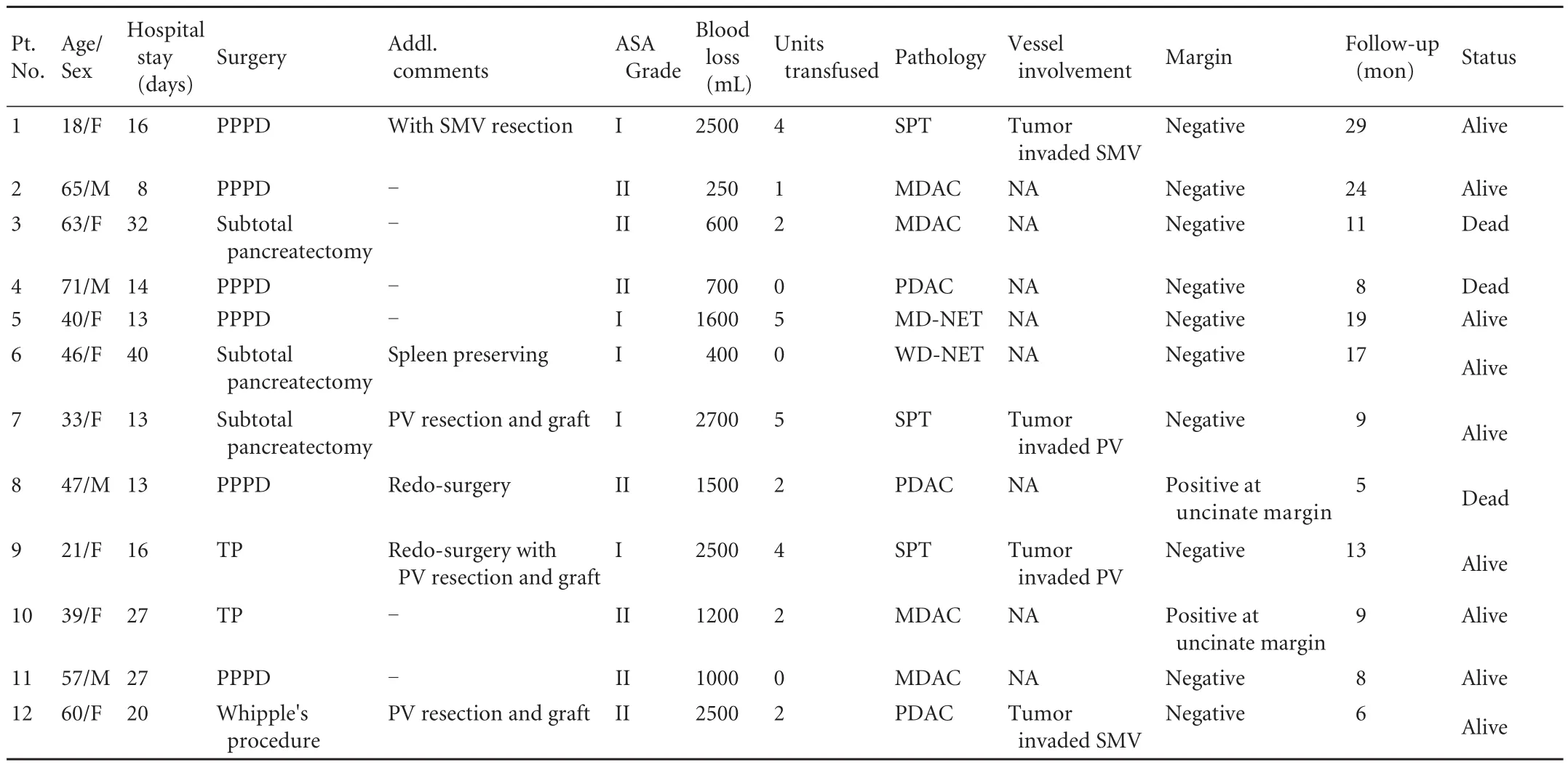

Patient demography and surgery-related data (Table 1)A total of 12 patients, 4 men and 8 women, had a median age of 46.50 years (range 18-71 years). Six patients underwent PPPD, 1 had a classical Whipple's procedure,2 TP, and 3 subtotal pancreatectomies.

Four of the 12 patients required some form of vascular resection or reconstruction, while 8 did not require any form of vascular resection. The median blood loss was 1350 mL (range 250-2700 mL) and a median of 2 units/patient was transfused (range 0-5 units). In 10 patients, a complete (R0) resection was made. Two patients were found to have microscopically positive margins at the uncinate margin on fi nal histopathology.

The median length of hospital stay was 16 days (range 8-40 days). Post-operative complications occurred in 5 out of the 12 patients (41.67%) and there were no peri-operative deaths. The complications encountered included grade C post-operative pancreatic fi stula in 2 patients, and delayed gastric emptying, subhepatic collection and chyle leak in one patient each.

Seven out of the 12 patients had pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, 3 patients had solid pseudopapillary tumor (SPT), and 2 had neuroendocrine tumor (NET).

Follow-up data

The median follow-up was 10 months (range 5-29 months). Eight patients were alive at last follow-upwithout evidence of any recurrent disease. One patient was alive with recurrent disease, while three patients died from metastatic disease 5, 8 and 11 months after surgery.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of recipients and donors

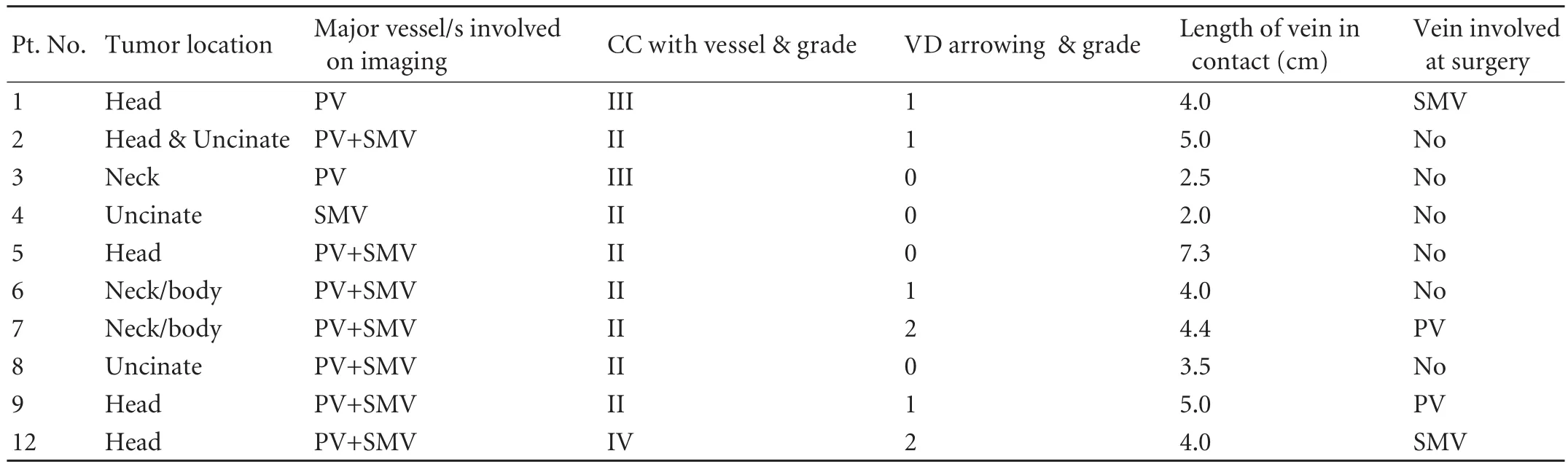

Table 2. Image analysis

Fig. MDCT images demonstrating the parameters studied in the patients with borderline resectable tumors. A, B: Axial postcontrast CT section showing circumferential contact (venous deformity grade 0) of pancreatic head adenocarcinoma with SMV over 117°. The patient did not require VR; C: Axial postcontrast CT sections showing pancreatic head neuroendocrine tumor abutting the SMV (black arrow) for approximately 7 cm but without causing vessel narrowing. The patient did not require VR; D: Coronal reformation on a 16-slice MDCT scanner showing the entire length of pancreatic head SPT/SPEN in contact with the MPV and SMV (CC was grade II). Grade I (<50%) luminal narrowing was present in the distal part of the venous segment. Patient did not require VR.

Image analysis (Table 2)

The 10 patients in whom a complete resection was achieved were subjected to the assessment of the radiologic criteria. One patient had grade I, 6 had grade II, 2 had grade III and 1 had grade IV CC with the involvement of the SMV or PV. Four of the 10 patients had grade 0 VD, 4 had grade 1 VD, and 2 had grade 2 VD. The LC of tumor to vein ranged from 2 to 7.3 cm.

The surgical records showed that 4 patients required a venous resection. One of these had grade IV contact with the vein and grade 2 VD. One patient had grade III circumferential contact of tumor involving the SMV or PV; and another had grade II CC but grade 2 VD. Only one of the four patients had a grade II CC and grade 1 VD.

Criteria for predicting the need for vascular resection in patients with BRT (Table 2)

In consideration of the individual radiological parameters in relation to the actual need for venous resection, a) CC-VR and reconstruction was required in 2 of 3 patients with CC ≥grade III and 2 of 7 patients with CC <grade III, and b)VD-VR and reconstruction was required in 2 of 2 patients with VD ≥grade 2 and 2 of 8 patients with VD <grade 2.

LC did not appear to have any relation to the need for VR.

Three of 4 patients with CC ≥grade III and VD ≥grade 2 required VR while only 1 of 6 patients with CC<grade III and VD <grade 2 required VR. These two parameters could thus serve as criteria for de fi ning those patients with suspected venous involvement who would actually require VRs.

Discussion

Pancreatic cancer is insidious in onset, leading to nearly two-thirds of patients having locally advanced or metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis. This dismal picture implies that only 20% of patients present with potentially resectable disease and it is this group of patients who have received the maximum attention of the surgical community. Conventionally, pancreatic cancers have been classi fi ed as resectable (stage I or II),locally advanced (stage III) or metastatic (stage IV).[2,13]However, over the past few years, a distinct subset of patients with pancreatic cancer has emerged, i.e. patients with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer.[2-6]BRTs are those which satisfy any one of the following criteria:1. ≤180° tumor abutment with the SMA; 2. Short segment (1.5 cm) encasement or occlusion of the PV/SMV; 3. Encasement of short segment of hepatic artery,but not up to celiac axis; 4. Encasement of GDA up to hepatic arterial origin; and 5. ≤180° tumor abutment with the PV and SMV.

Surgery has been the mainstay of treatment for pancreatic cancer, with achievement of a complete resection being linked to best possible outcome.[14-16]However, multimodality treatment which includes chemotherapy and radiotherapy is currently being extensively investigated, especially in the BR group of pancreatic cancer patients for the following two reasons:[6]1) It is necessary to achieve a marginnegative resection; and 2) Neo-adjuvant protocols will help identify those patients with better tumor biology who are more likely to bene fi t from surgery after neoadjuvant therapy.

Regarding borderline resectable pancreatic cancer,while the tumor relationship to the arterial structures as seen on optimal CT imaging and based on the above criteria accurately predicts the arterial involvement, the same cannot be said of venous imaging. While tumor encasement of the SMV (>180° contact with tumor) or venous occlusion is predictive of venous involvement,the same cannot be concluded about tumor abutment to the SMV (tumor-vessel contact <180°).

Lu et al[17]studied the vascular relationships of pancreatic adenocarcinomas on CT imaging and graded them on a 0-4 scale. Grade 0 was designated if there was a plane between tumor and vessel, grade 1, when the tumor-vessel contact was less than or equal to 90°,grade 2 when the tumor-vessel contact was greater than 90° up to 180°, grade 3 when the tumor-vessel contact exceeded 180° but was less than 270°, and grade 4 when the tumor-vessel contact was greater than or equal to 270°. In their series, 4 of 7 vessels with a grade 2 relation required vascular resection. However, in one patient in their study graded as 3, the tumor was easily separated from the SMV. Their data seemed to indicate that mere contiguity of tumor to vein does not signify invasion.

In addition to tumor-vessel contact, our analysis recorded and graded additional features such as VD and LC of the tumor with the vessels. Based on these we were able to determine that while LC did not appear to aid differentiation between the patients who underwent VR and those who did not, VD was helpful especially in patients who were graded as 2 (>50% luminal narrowing).

Based on our fi ndings in this cohort of patients, we were able to determine that stratifying the extent of VD is able to add value to the existing MD Anderson Criteria[6]in order to predict which patients with BRT would actually require VRs. The proposed criteria,however, need to be validated in larger cohorts.

A limitation of our study is the small number of cases. However, considering that two thirds of patients with pancreatic cancer present with locally advanced and/or metastatic disease, and 15%-20% of them present with resectable disease,[6]that would leave only a small proportion of patients with BRT in any surgical practice. What could also be regarded as a limitation is the heterogeneity of tumor pathology. However,irrespective of the procedure, certain intra-operative steps are common to them all, i.e. dissection of the area around the pancreatic neck to assess for venous/arterial resection or salvage and yet ensure an R0 resection. It is also pertinent to note that the ultimate aim, even for tumors other than pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas,is an R0 resection. Moreover, vascular involvement is well known even in neuroendocrine tumors and even solid pseudopapillary tumors. To overcome these two limitations, we would encourage other surgeons to assess the accuracy of our criteria in their own practice.Although conclusions from a diverse group could be dif fi cult to justify at present, our observations suggest that it would be worthwhile to closely follow up the radiologic-surgical relationships of these tumors in larger prospective studies.

In a recent expert consensus statement,[18]the de fi nitions of localized and resectable tumors (group 1)and also that of borderline resectable tumors (group 2)have been well laid out. We believe our experience with borderline resectable tumors demonstrates the need to identify a further subgroup that should be included between groups 1 and 2.

The bene fi t of performing a venous resection up front when venous involvement has been suggested on preoperative imaging is questioned based on our series which raises the possibility of venous salvage in such patients. By using vein salvage, we achieved an R0 resection in 8/12 patients. In the two patients in whom an R1 resection was achieved, the positive margin was away from the vein.

Finally, accurate pre-treatment assessment of resectability is crucial to design appropriate preoperative protocols of the operating team. Preoperative awareness of vascular involvement will facilitate intraoperative technical approaches and minimize the potential danger of adding a vascular procedure to the already formidable task at hand.[19,20]Pancreatic resections are dif fi cult and demanding resections to begin with and every effort must be made to avoid adding a vascular resection as far as possible without compromising oncologic radicality.

In conclusion, it is possible to achieve a complete resection at the fi rst instance in some patients who are found to have BRTs on preoperative imaging.Preoperative MDCT-based grading systems and our proposed criteria can help identify such patients. This would help avoid delayed curative resections in such patients.

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: Not needed.

Contributors: SSV and AS proposed the study and contributed to the design. AS, SSV and BSG wrote the fi rst draft. BSG. IS,DMA and HR collected and analyzed the data. SSV, AS and BSG contributed to the interpretation of the study and to further drafts. SPJ reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content. SSV is the guarantor.

Competing interest: No bene fi ts in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Shukla PJ, Barreto SG, Mohandas KM, Shrikhande SV. De fi ning the role of surgery for complications after pancreatoduodenectomy. ANZ J Surg 2009;79:33-37.

2 Kuvshinoff BW, Bryer MP. Treatment of resectable and locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Cancer Control 2000;7:428-436.

3 National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Practice Guidelines for Pancreatic cancer. Available from http://www.nccn.org.

4 Katz MH, Pisters PW, Evans DB, Sun CC, Lee JE, Fleming JB,et al. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: the importance of this emerging stage of disease. J Am Coll Surg 2008;206:833-848.

5 Springett GM, Hoffe SE. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: on the edge of survival. Cancer Control 2008;15:295-307.

6 Varadhachary GR, Tamm EP, Abbruzzese JL, Xiong HQ,Crane CH, Wang H, et al. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: de fi nitions, management, and role of preoperative therapy. Ann Surg Oncol 2006;13:1035-1046.

7 Tucker ON, Rela M. Controversies in the management of borderline resectable proximal pancreatic adenocarcinoma with vascular involvement. HPB Surg 2008;2008:839503.

8 Barreto G, D'Souza MA, Shukla PJ, Shrikhande SV. The gray zone between postpancreaticoduodenectomy collections and pancreatic fi stula. Pancreas 2008;37:422-425.

9 Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J,et al. Postoperative pancreatic fi stula: an international study group (ISGPF) de fi nition. Surgery 2005;138:8-13.

10 Shrikhande SV, Barreto G, Shukla PJ. Pancreatic fi stula after pancreaticoduodenectomy: the impact of a standardized technique of pancreaticojejunostomy. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2008;393:87-91.

11 Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, et al. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE)after pancreatic surgery: a suggested de fi nition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS).Surgery 2007;142:761-768.

12 Wente MN, Veit JA, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A,Gouma DJ, et al. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH):an International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS)de fi nition. Surgery 2007;142:20-25.

13 Fuhrman GM, Leach SD, Staley CA, Cusack JC,Charnsangavej C, Cleary KR, et al. Rationale for en bloc vein resection in the treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma adherent to the superior mesenteric-portal vein con fl uence.Pancreatic Tumor Study Group. Ann Surg 1996;223:154-162.

14 Campbell F, Smith RA, Whelan P, Sutton R, Raraty M,Neoptolemos JP, et al. Classi fi cation of R1 resections for pancreatic cancer: the prognostic relevance of tumour involvement within 1 mm of a resection margin.Histopathology 2009;55:277-283.

15 Kato K, Yamada S, Sugimoto H, Kanazumi N, Nomoto S,Takeda S, et al. Prognostic factors for survival after extended pancreatectomy for pancreatic head cancer: in fl uence of resection margin status on survival. Pancreas 2009;38:605-612.

16 Shimada K, Sakamoto Y, Nara S, Esaki M, Kosuge T, Hiraoka N. Analysis of 5-year survivors after a macroscopic curative pancreatectomy for invasive ductal adenocarcinoma. World J Surg 2010;34:1908-1915.

17 Lu DS, Reber HA, Krasny RM, Kadell BM, Sayre J. Local staging of pancreatic cancer: criteria for unresectability of major vessels as revealed by pancreatic-phase, thin-section helical CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1997;168:1439-1443.

18 Callery MP, Chang KJ, Fishman EK, Talamonti MS, William Traverso L, Linehan DC. Pretreatment assessment of resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: expert consensus statement. Ann Surg Oncol 2009;16:1727-1733.

19 Shukla PJ, Barreto SG, Kulkarni A, Nagarajan G, Fingerhut A.Vascular anomalies encountered during pancreatoduodenectomy: do they in fl uence outcomes? Ann Surg Oncol 2010;17:186-193.

20 Talamonti M. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: a new classi fi cation for an old challenge. Ann Surg Oncol 2006;13:1019-1020.

BACKGROUND: The ideal treatment of patients with "borderline resectable pancreatic tumors (BRTs)" needs to be established.Current protocols advise neoadjuvant chemo(radio)therapy,although some patients may appear to have BRT on preoperative imaging and a complete resection may be achieved without the need for vascular resection. The aim of the present study was to identify speci fi c fi ndings on preoperative imaging that could help predict in which patients with BRT a complete resection, with or without vascular resection (VR), could be achieved.

METHODS: Twelve patients with BRTs were identi fi ed. Tumor location, maximum degree of circumferential contact (CC),length of contact of the tumor with major vessels (LC), and luminal narrowing of vessels at the point of contact with the tumor (venous deformity, VD) were graded on preoperatively acquired multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) images and then compared with the intraoperative fi ndings and need for VR.

RESULTS: A complete resection (R0) was achieved in 10 patients with 2 having microscopic positive margins (R1) on histopathology at the uncinate margin. Four of the 10 patients required VR (40%). In 3 of the 4 patients whose tumors required VRs, CC was ≥grade III and VD was grade 2. LC did not in fl uence the need for VR.CONCLUSIONS: It is possible to achieve a complete resection at the fi rst instance in patients found to have BRTs on preoperative imaging. Preoperative MDCT-based grading systems and our proposed criteria may help identify such patients, thus avoiding any delay in curative resections in such patients.

Author Af fi liations: Department of Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Surgical Oncology (Shrikhande SV, Ingle S, D'Souza MA and Shukla PJ), Department of Radiology (Arya S), and Clinical Research Secretariat (Hawaldar R), Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, India; Department of Surgery, Royal Adelaide Hospital, Adelaide, Australia (Barreto SG)

Shailesh V Shrikhande, Professor and Consultant Surgeon, Department of Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Surgical Oncology, Tata Memorial Hospital, Ernest Borges Marg, Parel, Mumbai 400 012, India (Tel: +91-22-2417 7173; Fax: + 91-22-2414 8114; Email: shailushrikhande@hotmail.com, shailesh.shrikhande@pancreaticcancerindia.org)

© 2011, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

October 7, 2010

Accepted after revision March 3, 2011

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Clinical features and treatment of sump syndrome following hepaticojejunostomy

- Current surgical management of pancreatic endocrine tumor liver metastases

- Dose requirement and complications of diluted and undiluted propofol for deep sedation in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

- Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma:an update

- Predictive value and main determinants of abnormal features of intraoperative cholangiography during cholecystectomy

- Emergency re-routing of anterior sector venous outflow for right lobe living donor liver transplantation including the middle hepatic vein