Success rate and complications of endoscopic extraction of common bile duct stones over 2 cm in diameter

2011-07-05XinJianWanZhengJieXuFengZhuandLeiLi

Xin-Jian Wan, Zheng-Jie Xu, Feng Zhu and Lei Li

Shanghai, China

Original Article / Biliary

Success rate and complications of endoscopic extraction of common bile duct stones over 2 cm in diameter

Xin-Jian Wan, Zheng-Jie Xu, Feng Zhu and Lei Li

Shanghai, China

BACKGROUND:Clinically, common bile duct (CBD) stones >2 cm are difficult to remove by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography(ERCP). To evaluate this observation, the rates of successful clearance of CBD stones and complications were compared between ERCP extraction of CBD stones of >2 cm and <2 cm in diameter.

METHODS:All patients who had undergone endoscopic extraction of CBD stones at the Endoscopy Center of Shanghai First People's Hospital from May 2004 to May 2008 were reviewed. Patients with CBD stones of >2 cm in diameter were enrolled in the >2 cm group. Two matched controls with CBD stones of <2 cm in diameter were selected for each enrolled patient (<2 cm group). Patient characteristics, success rates, and complications during and after ERCP were compared.

RESULTS:Seventy-two patients constituted the >2 cm group and 144 patients were in the <2 cm group. No significant differences were found in the patient characteristics, except for stone size and CBD diameter. Both the overall success rate and the success rate in the first ERCP session were lower in the >2 cm group (77.8% and 58.3%, respectively) than in the <2 cm group (91.7% and 83.3%,P<0.01). During ERCP, the incidence of hypoxemia (30.6%) and hemorrhaging papillae (18.1%) in the >2 cm group was higher than in the <2 cm group (13.2% and 6.3%,P<0.05). After ERCP, the rates of delayed papillae hemorrhage (13.9%), hyperamylasemia (23.6%), acute pancreatitis (8.3%) and biliary infection (18.1%) were higher in the >2 cm group than in the <2 cm group (3.5%, 11.1%, 2.1%, and 2.8%, respectively,P<0.05).

CONCLUSION:The success rate of endoscopic extraction of CBD stones of >2 cm in diameter was lower but the complication rate was higher than that of stones of <2 cm in diameter.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2011; 10: 403-407)

endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; common bile duct diseases; gallstone

Introduction

Endoscopic treatment is now the first-line management option for common bile duct (CBD) stones. Endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST), first described in 1974, is the most frequently used endoscopic technique for clearance of stones from the bile duct. At present, the mainstream stone removal procedure is to combine EST with the Dormia basket or balloon catheter. Several studies have shown that 90% of CBD stones are effectively treated using this method.[1-7]However, as stone size increases, the degree of difficulty in using this technique increases.

According to our clinical experience, CBD stones of >2 cm in diameter are difficult to remove by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). To further evaluate this observation, in this retrospective study the rates of successful clearance of CBD stones and complications were compared between ERCP extraction of stones of >2 cm and <2 cm in diameter at an endoscopy center with a workload of >800 ERCPs/year.

Methods

Patients and data collection

In this retrospective study, we searched the gastrointestinal endoscopy database for all patients who had undergone endoscopic CBD stone extraction at the Endoscopy Center of Shanghai First People's Hospital from May 2004 to May 2008. All patients with CBD stones of >2 cm in diameter were enrolled (>2 cm group). Two matched controls from the same database with CBD stones of <2 cm in diameter (<2 cm group) were selected foreach enrolled patient. The two matched controls and their enrolled patients were similar in age and gender. All of the ERCP procedures in the study were conducted by one experienced endoscopist (Wan XJ; >2500 career ERCPs, with a workload of >300 ERCPs/year), and endoscopic stone extraction was routinely preceded by EST.

Endoscopic procedure and instruments

Intravenous sedatives (pethidine and diazepam) were administered prior to the ERCP procedure in all patients. The size, location, and number of stones and diameter of the CBD were obtained by radiologic examination. The size (maximum transverse diameter) of the stone and CBD was measured after correction for magnification using the known diameter of an endoscope insertion tube and its apparent diameter on radiograph. EST then was conducted, and the length of incision was tailored to the size of the stone. The stone was removed with a Dormia basket, balloon-tip catheter, or mechanical lithotripter. The extraction procedure was repeated until no stones were found fluoroscopically. If residual small stones that could not be identified on radiographs were suspected, a nasobiliary drain was placed temporarily. ERCP with a further attempt at CBD clearance was performed in a later session within 3 to 7 days. The nasobiliary drain was also used in patients with cholangitis (i.e., biliary infection characterized by fever, upper abdominal pain, white blood cell elevation, and purulent bile). If the stone could not be extracted completely within 1 hour and/or severe edema or bleeding of papillae (i.e., hemorrhaging papillae) and/ or other complications occurred, the procedure was ended and a nasobiliary drain was placed. In these cases, another extraction session was considered and scheduled within 3 to 7 days. If the stone could not be broken and extracted, a nasobiliary drain was placed and the patient was prepared for surgery (open exploration of the CBD) unless he/she had any contraindication for surgery. For patients who could not undergo surgery, stents were placed immediately to palliate symptoms.

Endoscopes and instruments used included the following: Olympus JF-V260 and Olympus TJF-240 duodenoscopes; ERCP catheter (PR-40, Olympus, Japan); guide wire (Microvisive, 5619, USA); Dormia basket (BML-2Q, Olympus); balloon-tip catheter (B7-2Q, Olympus); UES-20 high frequency electronic power; mechanical lithotripter (BML-4Q, Olympus) and emergency mechanical lithotripter (BML-110A-1, Olympus); and plastic stents and nasobiliary drains (Olympus).

Evaluation of success and complications

The complete removal of all stones was defined as success. Overall success included success in the first and other sessions combined. Failure was defined as failure of stone extraction and cessation of the procedure due to severe complications. For these patients, surgery was performed or a stent was placed to palliate symptoms.

Perforation, hemorrhage of papillae, hypoxemia and cardiac dysrhythmia were monitored during the ERCP procedure. After ERCP, complications such as delayed hemorrhage of papillae, hyperamylasemia, acute pancreatitis, biliary infection, and sepsis (low blood pressure and a blood culture positive for bacteria) were noted.

Statistical analysis

Data were put into Microsoft Excel 2003 and converted into SPSS 13.0 format for analysis. Categorical data were presented as frequencies (percentages) and analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. Quantitative data were summarized by the mean±SD and analyzed using Student'sttest. All tests were two-sided and aPvalue of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

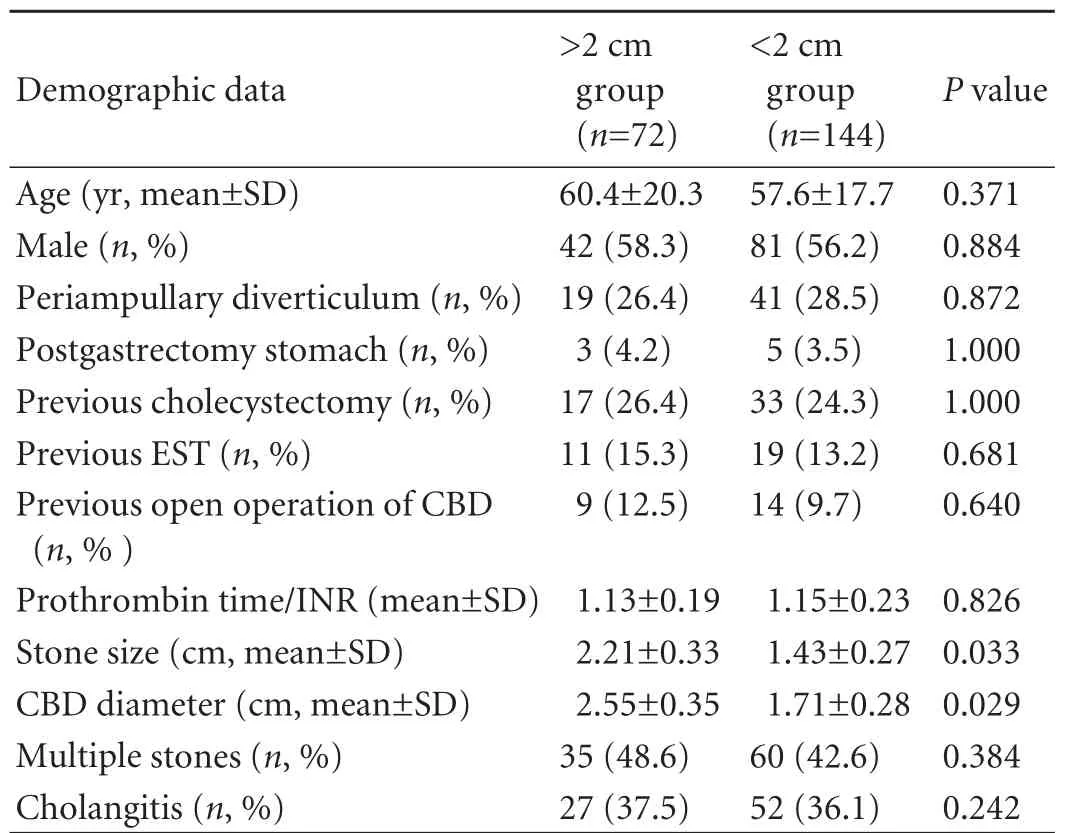

From May 2004 to May 2008, a total of 72 consecutive patients with >2 cm diameter CBD stones underwent therapeutic ERCP in our center; 144 patients with <2 cm diameter CBD stones were selected as matched controls from the same database. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the two groups. There were no significant differences between the groups with regard to the sex ratio, age, periampullary diverticulum, postgastrectomy stomach,previous cholecystectomy, previous EST, previous open operation of CBD, multiple stones (≥2) ratio, prothrombin time/INR and concomitant cholangitis. Both the stone size and CBD diameter in the >2 cm group were significantly larger than those in the <2 cm group.

Table 1. Patient characteristics

Success rate of endoscopic stone extraction

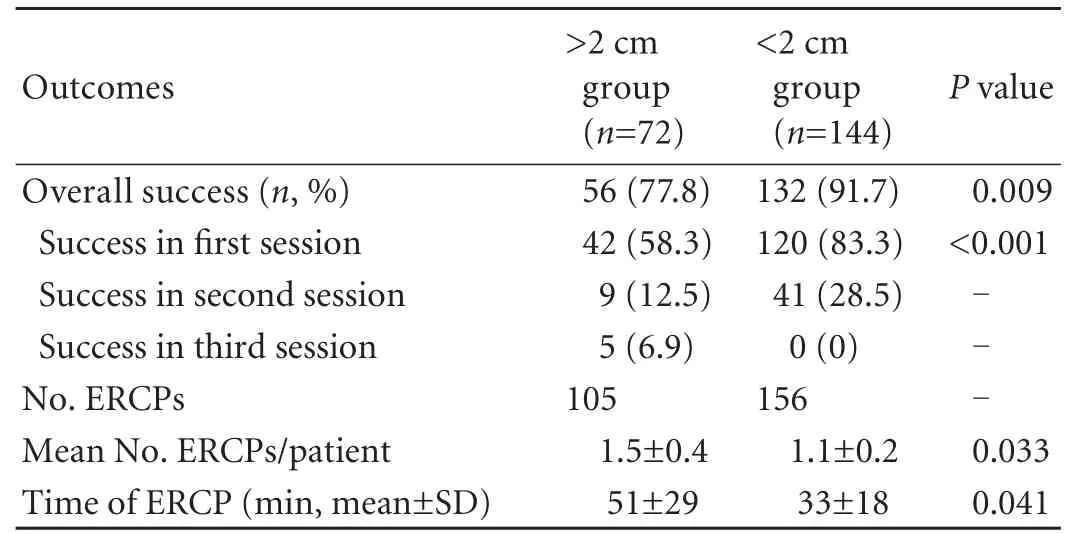

In the >2 cm group, 105 ERCP procedures were performed on the 72 patients (mean 1.5/patient). In the <2 cm group, 156 procedures were performed in the 144 patients (mean 1.1/patient). The overall success rate in the >2 cm group was significantly lower than that in the <2 cm group (77.8% vs 91.7%). The success rate in the first ERCP session of the >2 cm group was also significantly lower than that of the <2 cm group (58.3% vs 83.3%). The time of a procedure in the >2 cm group was significantly longer than that in the <2 cm group (Table 2).

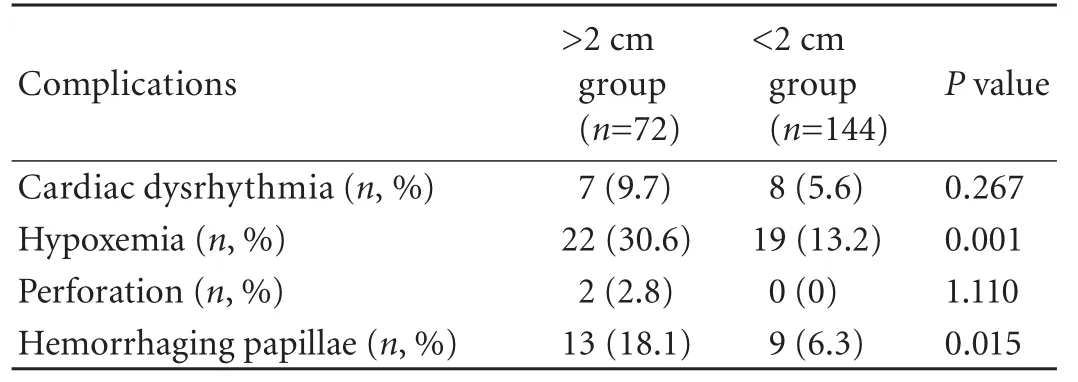

Immediate complications of ERCP

During ERCP, rates of cardiac dysrhythmia were similar in the two groups, whereas the incidence of hypoxemia was significantly higher in the >2 cm group than in the <2 cm group (30.6% vs 13.2%). Perforation occurred in two patients in the >2 cm group, whereas none occurred in the <2 cm group; however, this difference was not statistically significant. The rate of hemorrhaging papillae in the >2 cm group was significantly higher than in the <2 cm group (18.1% vs 6.3%) (Table 3).

Table 2. Outcomes of ERCP

Table 3. Immediate complications of ERCP

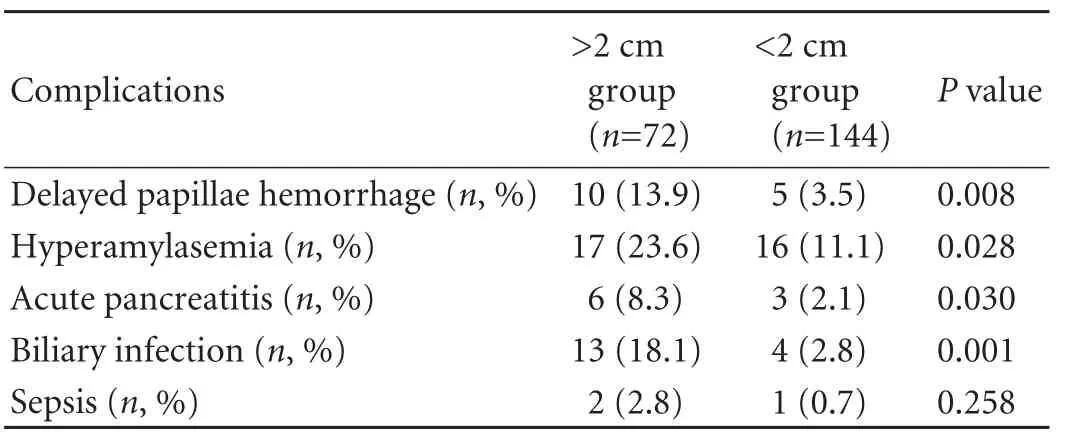

Late complications of ERCP

After ERCP, the incidence of delayed papillae hemorrhaging was significantly higher in the >2 cm group than in the <2 cm group (13.9% vs 3.5%). Both hyperamylasemia and acute pancreatitis were significantly more frequent in the >2 cm group than in the <2 cm group (23.6% vs 11.1%, and 8.3% vs 2.1%, respectively). Biliary infection occurred in 13 patients (18.1%) in the >2 cm group, which and it was more frequently than in the <2 cm group (2.8%). Sepsis occurred in 2 patients (2.8%) in the >2 cm group and in 1 patient (0.7%) in the <2 cm group; there was no statistical difference in the rates of sepsis between the two groups (Table 4).

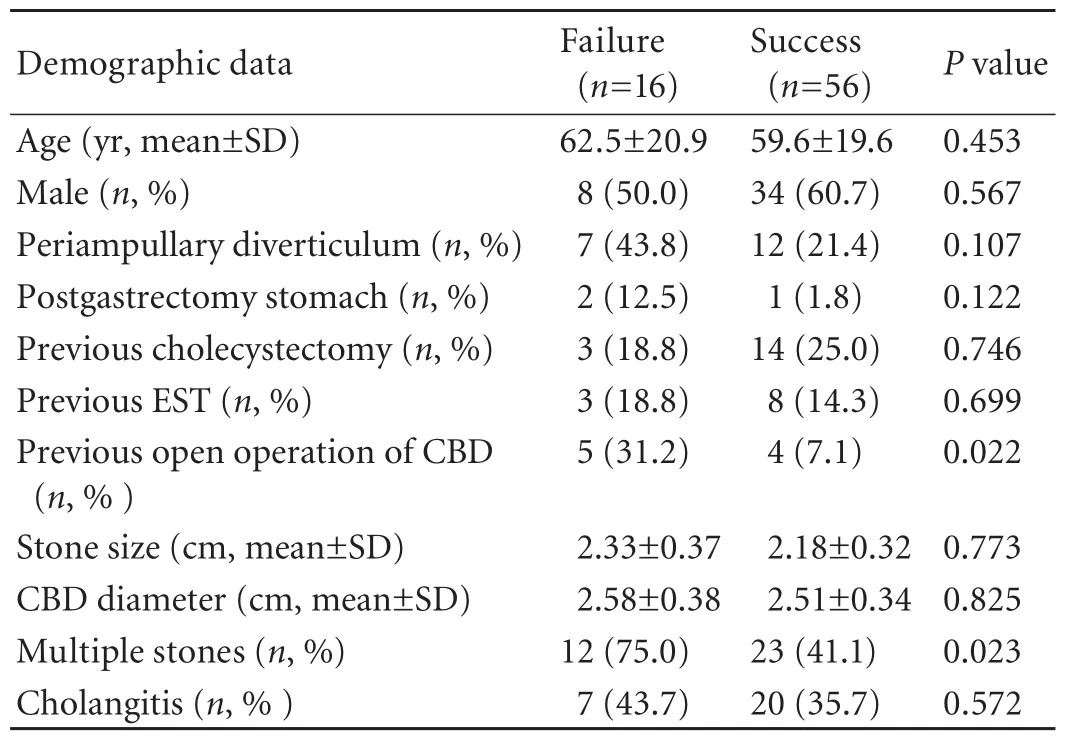

Comparative data for patients with successful and unsuccessful ERCP for >2 cm CBD stones

Comparative data for patients with successful and unsuccessful ERCP for >2 cm CBD stones are given in Table 5. Of the various factors analyzed, previous open operation of CBD and multiple stones were significant factors associated with failure of ERCP for >2 cm CBD stones.

Table 4. Late complications of ERCP

Table 5. Comparative data for patients with successful and unsuccessful ERCP for >2 cm CBD stones

Discussion

In the present study, the success rate of endoscopic stone extraction for >2 cm diameter CBD stones was lower and its complication rates were higher than those of the same treatment for <2 cm stones. In this study, the overall clearance rate of >2 cm stones was 77.8%, which was significantly lower than that (91.7%) of <2 cm stones. Furthermore, the larger the stones, the more treatment sessions were needed. The success rate of the first ERCP session of the >2 cm group was only 58.3%, whereas that of the <2 cm group was 83.3%.

Researchers have long believed that large stone size is a major factor accounting for failure of endoscopic extraction. The importance of size for successful endoscopic extraction of CBD stones was first analyzed in 1993. One hundred patients with CBD stones received ERCP, and the success of the procedure differed significantly when the size was analyzed (the median size for successful clearance was 1 cm and for unsuccessful clearance was 1.8 cm, P<0.001). Successful removal occurred in all patients with stones <1.0 cm in diameter, but removal was successful in only 12% of patients with stones >1.5 cm.[8]

Several options are available for large stones that cannot be removed directly through a basket or balloon catheter; they may be crushed using simple mechanical lithotripsy. In addition, the following procedures may be used to treat large bile duct stones: electrohydraulic lithotripsy, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, and laser therapy. However, these procedures require specialized and costly equipment. Currently, mechanical lithotripsy is the most commonly used technique for large stones. The reported success rate of fragmentation by basket mechanical lithotripsy ranges from 82% to 100%.[1-7]

Continuing improvements in the design and construction materials make mechanical lithotripsy easier to use and more effective, and the success rate of large stone removal has greatly increased. In a prospective randomized controlled trial reported by Heo, 29 out of 30 patients (96.7%) had complete CBD clearance after lithotripsy of large stones (>1.5 cm).[9]Chang et al[10]reported that of 304 patients with CBD stones >1.5 cm diameter, 272 had stones successfully removed by mechanical lithotripsy (success rate about 90%). In 2007, Kim et al[11]analyzed 102 patients undergoing endoscopic extraction and found that stone diameter >1.5 cm was not an independent contributor to technical difficulty.

However, the successful removal rates of CBD stones of >2 cm in diameter are not very high. Schneider et al[7]reported that in 209 patients undergoing mechanical lithotripsy, the overall success rate was 88%, whereas that of stones of >2.0 cm in diameter was 79%. Similarly, in our study the clearance rate of >2 cm diameter stones was 77.8%, which was significantly lower than that of <2 cm stones (91.7%). Furthermore, the larger the stones, the more treatment sessions were needed. These data suggest that CBD stones of >2 cm in diameter remain a challenge to mechanical lithotripsy. It was also noted that failure of ERCP for >2 cm CBD stones was significantly associated with previous open operation of the CBD and multiple stones. With the advance of EST, both factors no longer influence endoscopic extraction for CBD stones >1.5 cm in diameter.[1,2,9,11-13]

The complication rates of endoscopic extraction for CBD stones of >2 cm diameter were higher during and after surgery. During the ERCP procedure, the incidence of hypoxemia and hemorrhaging papillae in patients with >2 cm diameter stones was significantly higher than in patients with stones of <2 cm in diameter. After the procedure, delayed papillae hemorrhage, hyperamylasemia, acute pancreatitis, and biliary infection in patients with >2 cm diameter stones were more frequent than in patients with <2 cm diameter stones. The complication incidence in patients with <2 cm diameter stones in our study is similar to that in the published data.[14-18]Therefore, we believe that the skill of our endoscopists was not responsible for the higher complication incidence in patients with >2 cm diameter stones. Clearly, extracting a larger CBD stone requires a larger sphincterotomy, which leads to a higher incidence of perforation and bleeding. The ERCP procedure for large CBD stones is often technically difficult and timeconsuming (as shown in this study), which can increase the risk of hypoxemia, pancreatitis, and biliary infection.

For patients whose CBD stones are refractory to endoscopic retrieval, stenting or surgery is the routine alternative approach.[19,20]Recently, the success rate of stone removal using endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation (EPLBD) was reported to reach 95% with a low complication rate, even for stones of less than 1.5 cm in diameter.[12,13]EPLBD involves a small sphincterotomy followed by balloon dilation using a 12-20 mm balloon. EPLBD theoretically combines the advantages of sphincterotomy and balloon dilation by increasing the efficacy of stone extraction while minimizing the complications of both EST and balloon dilation.[9,12,13]However, the effectiveness and safety of EPLBD for treating >2 cm diameter CBD stones has not yet been reported. In terms of surgery, laparoscopic exploration of the CBD with a rigid scope is a new and advantageous procedure which has been replacing open exploration of the CBD. In 2010, Tekin et al[21]reportedthat it can achieve high rates of clearance with minimal complications in patients in whom endoscopic removal of CBD stones is unsuccessful. In our study, in the patients with >2 cm CBD stones who had previous open operation of CBD and multiple stones, the success rate of routine EST was low. In these patients, new techniques of ERCP such as EPLBD or minimally invasive surgery such as laparoscopic exploration of the CBD may be a better choice.

In conclusion, we found that the success rate of endoscopic extraction of >2 cm diameter CBD stones was lower and its complications rates were higher than those of <2 cm diameter stones. These results may help redefine the definition of "large" CBD stones. If the diameter of the CBD stone is >2 cm, the patient's condition should be evaluated carefully to select the optimum management strategy. For patients who have had previous open operation of CBD and multiple stones, routine EST may be not the first choice. However, it should be noted that the present study is limited by a small sample size and it is a retrospective study. Further investigations are required to redefine the diameter of "large" CBD stones.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Contributors:WXJ proposed the study and performed all ERCP procedures. WXJ and XZJ wrote the first draft. ZF and LL analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts. WXJ is the guarantor.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Mohammad Alizadeh AH, Afzali ES, Mousavi M, Moaddab Y, Zali MR. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography outcome from a single referral center in Iran. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2010;9:428-432.

2 Samardzic J, Latic F, Kraljik D, Pitlovic V, Mrkovic H, Miskic D, et al. Treatment of common bile duct stones--is the role of ERCP changed in era of minimally invasive surgery? Med Arh 2010;64:187-188.

3 Rogers SJ, Cello JP, Horn JK, Siperstein AE, Schecter WP, Campbell AR, et al. Prospective randomized trial of LC+LCBDE vs ERCP/S+LC for common bile duct stone disease. Arch Surg 2010;145:28-33.

4 Riemann JF, Seuberth K, Demling L. Mechanical lithotripsy of common bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc 1985;31:207-210.

5 Chung SC, Leung JW, Leong HT, Li AK. Mechanical lithotripsy of large common bile duct stones using a basket. Br J Surg 1991;78:1448-1450.

6 Shaw MJ, Mackie RD, Moore JP, Dorsher PJ, Freeman ML, Meier PB, et al. Results of a multicenter trial using a mechanical lithotripter for the treatment of large bile duct stones. Am J Gastroenterol 1993;88:730-733.

7 Schneider MU, Matek W, Bauer R, Domschke W. Mechanical lithotripsy of bile duct stones in 209 patients--effect of technical advances. Endoscopy 1988;20:248-253.

8 Lauri A, Horton RC, Davidson BR, Burroughs AK, Dooley JS. Endoscopic extraction of bile duct stones: management related to stone size. Gut 1993;34:1718-1721.

9 Heo JH, Kang DH, Jung HJ, Kwon DS, An JK, Kim BS, et al. Endoscopic sphincterotomy plus large-balloon dilation versus endoscopic sphincterotomy for removal of bile-duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc 2007;66:720-726.

10 Chang WH, Chu CH, Wang TE, Chen MJ, Lin CC. Outcome of simple use of mechanical lithotripsy of difficult common bile duct stones. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:593-596.

11 Kim HJ, Choi HS, Park JH, Park DI, Cho YK, Sohn CI, et al. Factors influencing the technical difficulty of endoscopic clearance of bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc 2007;66: 1154-1160.

12 Kim HG, Cheon YK, Cho YD, Moon JH, Park do H, Lee TH, et al. Small sphincterotomy combined with endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation versus sphincterotomy. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15:4298-4304.

13 Attam R, Freeman ML. Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation for large common bile duct stones. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2009;16:618-623.

14 Papachristou GI, Baron TH. Complication of therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gut 2007; 56:854.

15 Salminen P, Laine S, Gullichsen R. Severe and fatal complications after ERCP: analysis of 2555 procedures in a single experienced center. Surg Endosc 2008;22:1965-1970.

16 Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, et al. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med 1996;335:909-918.

17 Christensen M, Matzen P, Schulze S, Rosenberg J. Complications of ERCP: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc 2004;60:721-731.

18 Loperfido S, Angelini G, Benedetti G, Chilovi F, Costan F, De Berardinis F, et al. Major early complications from diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc 1998;48:1-10.

19 Kubota Y, Takaoka M, Fujimura K, Ogura M, Kin H, Yamamoto S, et al. Endoscopic endoprosthesis for large stones in the common bile duct. Intern Med 1994;33:597-601.

20 Dufek V, Benes J, Chmel J, Kordac V. Biliary endoprosthesis in the treatment of large common bile duct stones. Endoscopy 1990;22:240.

21 Tekin A, Ogetman Z. Laparoscopic exploration of the common bile duct with a rigid scope in patients with problematic choledocholithiasis. World J Surg 2010;34:1894-1899.

Received September 14, 2010

Accepted after revision February 9, 2011

Author Affiliations: Department of Gastroenterology, Shanghai First People's Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University, Shanghai 200080, China (Wan XJ, Zhu F and Li L); Department of Gastroenterology, Xinhua Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University Medical School, Shanghai 200092, China (Xu ZJ)

Xin-Jian Wan, MD, Department of Gastroenterology, Shanghai First People's Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University, Shanghai 200080, China (Tel: 86-21-63240090; Fax: 86-21-63240825; Email: wanxj99@ 163.com)

© 2011, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Surgical treatment of Budd-Chiari syndrome: analysis of 221 cases

- Hepatitis C virus infection and biological falsepositive syphilis test: a single-center experience

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International (HBPD INT)

- Donor liver natural killer cells alleviate liver allograft acute rejection in rats

- Enteral supplementation with glycyl-glutamine improves intestinal barrier function after liver transplantation in rats

- Noninvasive indocyanine green plasma disappearance rate predicts early complications, graft failure or death after liver transplantation