Technical tailoring of pancreaticoduodenectomy in patients with hepatic artery anatomic variants

2011-07-03CristianLupascuDanAndronicCorinaUrsulescuCiprianVasilutaandNutuVlad

Cristian Lupascu, Dan Andronic, Corina Ursulescu, Ciprian Vasiluta and Nutu Vlad

Iasi, Romania

Clinical Summary

Technical tailoring of pancreaticoduodenectomy in patients with hepatic artery anatomic variants

Cristian Lupascu, Dan Andronic, Corina Ursulescu, Ciprian Vasiluta and Nutu Vlad

Iasi, Romania

BACKGROUND:Pancreaticoduodenectomy is the treatment of choice for periampullary and pancreatic head tumors. In case of hepatic artery abnormalities, early pancreatic transection during pancreaticoduodenectomy may prove inappropriate. Early retroportal lamina dissection improves exposure of the superior mesenteric vessels and anatomic variants of the hepatic artery, where safeguarding is mandatory.

METHOD:We describe our early retroportal lamina approach in patients with anatomic variants of the hepatic artery before pancreatic transection.

RESULTS:This approach was used during 42 pancreaticoduodenectomies with a hepatic artery anatomic variant which was spared in 40 patients. Arterial reconstruction was performed in 2 patients. Five patients with a hepatic artery variant and adenocarcinoma involving the portomesenteric junction required venous resection and reconstruction.

CONCLUSIONS:Early retroportal lamina dissection during pancreaticoduodenectomy in patients with hepatic artery anatomic variants enables easier exposure, avoiding injuries that might compromise the liver arterial supply. When the portomesenteric vein is involved, this approach facilitatesen bloc"no touch" venous resection and reconstruction.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2011; 10: 638-643)

pancreaticoduodenectomy; hepatic artery anatomic variants

Introduction

Pancreaticoduodenectomy is still considered a challenging operation with a postoperative mortality rate of less than 5% but a high morbidity rate of close to 40%, even in recent series.[1,2]It is particularly indicated for malignant tumors (pancreas head, Vater's ampulla, distal common bile duct and duodenal cancer) but also in the management of some benign lesions.[3]Knowledge of the hepatic artery anatomy is essential to prevent unnecessary surgical complications during pancreaticoduodenectomy. After Haller[4]described variants of the hepatic arteries in 1756, several reports have been published about hepatic artery anatomy. Nowadays, Michels' and Hyatt's international classifications of hepatic artery variants are commonly used.[5,6]Pancreaticoduodenectomy is usually performed backward, with transection of the pancreatic neck before retroportal lamina dissection close to the superior mesenteric artery.[7]The early retroportal lamina approach allows a better assessment of the variant pattern of the arterial blood supply to the liver, proper mobilization of the specimen from the vessels before pancreatic division and, if necessary, safe venous clamping.[8]

We described how we performed this pancreaticoduodenectomy variant, with pancreatic transection as the last step of resection.

Methods

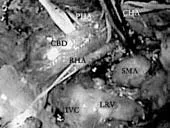

After the incision was made, the surgical exploration was completed by intraoperative ultrasonography. The pancreatic head was exposed by an extensive Kocher's maneuver, by dividing the reflection of the third duodenum to the proximity of the duodenojejunal flexure beneath the superior mesenteric vessels and mesentery, and opening of the lesser sac by separating the greater omentum from the transverse colon. We divided the right gastroepiploic vein and isolate the superior mesenteric vein early at the inferior edge of the pancreas(Fig. 1). Behind the pancreas, the dissection must pass beyond the aorta to get full posterior mobilization of the duodenopancreas to the patient's left, and highlight the plane between the superior mesenteric artery and the superior mesenteric vein. Extensive "Kocherization" allowed a good exposure of the aortocaval region for lymphadenectomy. Liver and peritoneal exploration was performed as well as palpation of the mesentery root and biopsy examination of the aortocaval nodes with frozen sections. A downwards retropancreatic dissection was performed within the Treitz fascia by revealing the inferior vena cava and its left side, the left renal vein with its upper margin and in between, in this angle, the origin of the superior mesenteric artery (Figs. 2, 3). This was completely separated on its right and posterior sides from the retroportal lamina, which was dissected step-by-step and removed along about 4-5 cm, from the origin of the artery to its entry into the mesentery. The dissection was kept in a frontal plane between the pancreas and superior mesenteric artery by rightward traction upon the retroportal lamina. We removed all the connective tissue, perivascular neural plexus and lymph nodes belonging to the posterior pancreaticoduodenal vessels, which make up the retroportal lamina. The origin of a right hepatic artery or a replaced common hepatic artery was properly distinguished at a point 1-2 cm beneath the superior mesenteric artery origin (Fig. 4). The portomesenteric vein was also freed from the pancreatic tissue and the right portion of the retroportal lamina which encloses it, by progressive exposure and gentle medial retraction (Figs. 3, 4). Using a vascular tape around the superior mesenteric artery, we safely separated it from the pancreatic tissue, portomesenteric vein and uncinate. The posterior and inferior pancreaticoduodenal arteries were divided. This operation was performed while the possible involvement to the superior mesenteric artery was ascertained. Further dissection in this area was performed after dissection of the porta hepatis. When the common and proper hepatic arteries existed as such, they were first isolated. We divided the right gastric vessels, identified and clamped the gastroduodenal artery to make sure that arterial flow either in the hepatic and gastric arteries remains normal and there is no unrecognized celiac trunk stenosis. The gastroduodenal artery was divided as well as the common bile duct above the entry of the cystic duct (Fig. 4). This improved the exposure of the suprapancreatic portal vein. During the lymphadenectomy around the portal vein, attention was paid to a hepatic artery anatomic variant arising from the superior mesenteric artery, the origin of which was already dissected. This variant vessel usually runs upwards behind the portal vein (Fig. 4). In case of areplaced common hepatic artery, after dividing the gastroduodenal artery, which is one of its branches, branches to the right and left liver must be preserved (Fig. 5). When an early division of a replaced common hepatic artery with an intrapancreatic course is encountered, the variant vessel should be set free from the retroportal lamina, from its origin, upwards to the porta hepatis (Fig. 5). When the right hepatic artery arises from the celiac trunk, it should be isolated behind the upper edge of the pancreas head and portal vein. To facilitate its dissection, the duodenopancreas was retracted inferomedially en bloc (Fig. 3). We advocated limited dissection along the right side of the superior mesenteric artery to avoid an extensive removal of the perivascular nervous plexus, resulting in postoperative intestinal motility troubles (diarrhea). The portomesenteric vein was entirely dissected by ligating all veins draining the uncinate. Since there was an avascular plane between the portal vein and the pancreatic neck, this was entirely exposed after this dissection. The division of the Treitz ligament, equally beneath the portomesenteric vein, allowed mobilization and retraction of the duodenojejunal junction, so that the specimen to be removed reached the right side of the mesenteric root. The proximal jejunum and the distal stomach were divided.

Fig. 1. Exposure of the superior mesenteric vein on the anterior third duodenum. SMV: superior mesenteric vein; S: stomach; D: duodenum; M: mesentery.

Fig. 2. Retropancreatic dissection with a replaced right hepatic artery originating in the superior mesenteric artery before retroportal lamina dissection and common bile duct division. PHA: proper hepatic artery; CHA: common hepatic artery; CBD: common bile duct; RHA: right hepatic artery; SMA: superior mesenteric artery; LRV: left renal vein; IVC: inferior vena cava.

Fig. 3. Retropancreatic dissection: the duodenopancreas with the tumor is retracted medially and to the left. CBD: common bile duct; PV: portal vein; IVC: inferior vena cava; RHA: right hepatic artery; SMA: superior mesenteric artery; LRV: left renal vein; SMV: superior mesenteric vein.

Fig. 4. Intraoperative image just before pancreatic transection; the superior mesenteric artery was freed from the retroportal lamina along 3-4 cm. GDA: gastroduodenal artery; PHA: proper hepatic artery; CHA: common hepatic artery; CBD: common bile duct; PV: portal vein; RHA: right hepatic artery; SMA: superior mesenteric artery; SMV: superior mesenteric vein; LRV: left renal vein; RPL: retroportal lamina; IVC: inferior vena cava.

Fig. 5. Exposure of a replaced common hepatic artery with early bifurcation within the pancreas parenchyma. PV: portal vein; RCHA: replaced common hepatic artery; CBD: common bile duct; SMA: superior mesenteric artery.

The last step of the resection is the transection of the pancreatic neck just in front of the portal vein. In our practice, when the tumor involved the portomesenteric confluence we performed en bloc mobilization and splenic vein control behind the body. The mesentery root and right colon were mobilized to perform en bloc resection and reconstruction after segmental venous resection. This maneuver is useful in case of limited portomesenteric invasion, to avoid grafting during venous reconstruction.

As for the reconstruction phase after pancreaticoduodenectomy, we always perform a pancreaticojejunal end-to-side "duct-to-mucosa" temporary stented anastomosis with 6-0 PDS sutures. Standard hepaticojejunostomy and gastrojejunostomy are the final steps of the procedure. Drain placement and postoperative care are similar to those for the standard procedure.

Results

In our surgical department, part of a high-volume university hospital, 134 consecutive patients underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy for periampullary and pancreatic head tumors between January 1, 2007, and November 30, 2010. Among them, 42 (31%) (23 females and 19 males, age range 41-76 years) who were preoperatively assessed by multidetector computed tomography had hepatic artery anatomic variants and underwent a retroportal lamina dissection during pancreaticoduodenectomy, as a standard procedure performed by a single team. Thirty-seven patients with preoperatively detected hepatic artery anatomic variants had malignant tumors of the pancreatic head or periampullary region and 5 had neuroendocrine tumors of the inferior pancreatic head (4 insulinomas and 1 malignant neuroendocrine tumor). Thirty-two patients had an accessory or replaced right hepatic artery arising from the superior mesenteric artery or celiac trunk. Ten patients had a replaced common hepatic artery originating in the superior mesenteric artery. In two patients with a replaced common hepatic artery originating from the superior mesenteric artery, the abnormal vessel was involved with an enlarged lymph node mass behind the pancreatic head. Segmental resection of the involved artery and arterialreconstruction were performed, using the reversed splenic artery in both patients. Five patients with hepatic artery variants and adenocarcinoma involving the portomesenteric vein required en bloc vascular resection, and mobilization of the right colon and mesentery root followed by mesentericoportal end-to-end anastomosis and reimplantation of the splenic vein. In the 7 patients requiring vascular reconstruction, clamping time did not exceed 18 minutes and anastomotic patency with normal blood flow was confirmed by Doppler ultrasonography at the end of the procedure. No significant intraoperative incidents were noted. The mean operative time was 290 minutes and the mean blood loss was 310 mL in this approach, compared with 315 minutes and 520 mL in the standard procedure group. No postoperative complications or mortality were noted, particularly related to this approach. The mortality rate in the 134 patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy was 3.73% and the morbidity was 34.32%. The mean length of hospitalization was 18.5 (11-34) days in the posterior approach group, compared with 19 days in the standard approach group. For the malignant tumors, an R0 resection was made in 35 patients and an R1 resection in 3 (microscopic involvement of the retroportal lamina). The median survival time for the 42-patient group was 23.6 months. Follow-up lasted until death or until the cut-off date of January 31, 2011. At the time of the last follow-up, 34 patients were still alive.

Discussion

Because of the recent decrease in mortality rate, pancreaticoduodenectomy is widely performed nowadays for tumors of the pancreatic head and periampullary region. Morbidity remains an important issue which is correlated with hemorrhage and remnant pancreatic stump "pathology". Since the first description of the technique by Whipple and Kausch, this operation has evolved over the years and become a routine surgery in trained surgical centers.[1,2,9,10]We have described here our technique of early retroportal lamina dissection during pancreaticoduodenectomy, on the right side of the superior mesenteric artery, before pancreatic transection. This modified technique was initially proposed by Pessaux et al[8]starting from the anatomical studies regarding the retroportal lamina. We believe this technique to be a suitable option in cases of hepatic artery anatomic variants, particularly the right hepatic artery originating from the superior mesenteric artery or celiac trunk, and a replaced common hepatic artery arising from the superior mesenteric artery or aorta, especially when the tumor involves the portomesenteric vein. Therefore, en bloc "no touch" resection with pancreatic division of the body and venous reconstruction are required.[11-14]Classically, Whipple's procedure includes the creation of a tunnel between the pancreatic neck and the underlying portomesenteric confluence, followed by neck transection. Accordingly, pancreatic continuity is interrupted before the radicality of the resection can be assessed close to the superior mesenteric artery. Even in some recent series, nonradical pancreaticoduodenectomy still represents 9% to 25% of cases.[15]Moreover, in the standard approach, dissection of a hepatic artery anatomic variant coming from the superior mesenteric artery is usually performed late, when bleeding from the resection specimen decreases their exposure.[16]Early neck transection is not suitable when the neck is involved by the tumor, as in pancreatic head cancer involving the portomesenteric vein.[12,13]One of the difficulties of pancreaticoduodenectomy is the variability of peripancreatic vessels anatomy. Assessment of variant patterns of the arterial supply to the liver in patients who are about to undergo this procedure is a challenging but mandatory procedure, that can avoid or minimize unnecessary complications, such as fatal hepatic injury.[16,17]Accidental ligation of a hepatic artery anatomic variant may result in hepatic necrosis, ischemic biliary injury or anastomotic complications.[18-20]The importance of sparing it lies not so much in preventing hepatic ischemia, but in preventing a breakdown of bilioenteric anastomosis, because the blood supply to the cranial part of the bile duct is entirely dependent on the right hepatic artery after pancreaticoduodenectomy.[18-21]Preoperative assessment of peripancreatic vascular patterns (variants, strictures) by imaging methods is of upmost importance for the surgeon. Multidetector computed tomography with angiography is the method of choice.[22]The most likely hepatic artery anatomic variant expected during planning or performing pancreaticoduodenectomy is a replaced or accessory right hepatic artery (10%-11%),[19-21]followed by a replaced common hepatic artery arising from the superior mesenteric artery (2%-3%). These vessels may course behind, within the pancreas head or along its ventral side.[17-19]A right hepatic artery or replaced common hepatic artery coursing within pancreas parenchyma is preserved by dividing this parenchyma.[21]In our opinion, this anatomic arterial variant must be dissected close to its origin from the superior mesenteric artery or celiac trunk and then along its retro- or intra-pancreatic course, under direct vision, towards the porta hepatis. In our patients, 31 such vascular variants coursedalong the posterior side and 11 within the pancreas. Before dissecting the variant hepatic artery, we could not confirm its course. Ductal carcinoma with limited venous involvement can be resected with a long-term survival similar to that after radical resection without venous involvement.[12,13]Venous resection is best performed en bloc "no touch" (with no intraportal tumor dissemination) to obtain disease-free margins, since the retroportal lamina is usually involved in these cases.[23]The technique we use results in the tumor being attached only to the involved portomesenteric vein, so clamping it may be easier and shorter. Mobilization of the right colon and mesentery root is useful to avoid grafting during reconstruction of the portal vein.[24]In case of tumoral arterial involvement, arterial resection and reconstruction of a replaced hepatic artery can be done using the splenic artery. It is expected that, because pancreatic transection is performed late, congestion and bleeding are less likely, whereas venous drainage of both the specimen and bowel are compromised minimally during the procedure.[16,25]Our preliminary findings reveal less operative bleeding than in the standard approach (probably due to early ligation of the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery and less bleeding time from the remnant pancreas before pancreaticojejunostomy) but these findings require further prospective studies comparing our approach to the standard procedure, since there is no consensus worldwide. Nevertheless, we should consider that the expertise required is higher in standard Whipple's procedure than in the posterior approach pancreaticoduodenectomy.

To our knowledge, there is no study comparing the posterior approach pancreaticoduodenectomy with standard Whipple's procedure. An objective comparison should involve a randomized prospective study on two matching groups in terms of number, age, pathology findings (type of tumor, location, TNM staging, tumor grading, and tumor vascular invasion), surgical experience, operative time, blood loss, and outcome (postoperative length of stay, in-hospital mortality and morbidity, survival time). Those will be addressed in one of our ongoing studies.

In conclusion, early retroportal lamina dissection during pancreaticoduodenectomy allows easier exposure of abnormal hepatic arteries and better detection of mesentericoportal invasion. Early control of the superior mesenteric artery enables easier safeguarding of a hepatic artery anatomic variant and an early selection of patients, avoiding the "point of no return" (in terms of resectability, by assessing the superior mesenteric artery infiltration). We advocate this approach in cases of hepatic artery variants arising from the superior mesenteric artery or celiac trunk, especially in those with additional limited involvement of the portomesenteric vein.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Contributors:LC, AD, VC and VN were members of the operating teams. LC was senior member of all operating teams. AD and VC wrote the first draft. UC was the senior Imaging Department member of the team. All authors contributed to further drafts. LC is the guarantor.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, Lillemoe KD, Pitt HA, Talamini MA, et al. Six hundred fifty consecutive pancreatico duodenectomies in the 1990s: pathology, complications, and outcomes. Ann Surg 1997;226:248-260.

2 Balcom JH 4th, Rattner DW, Warshaw AL, Chang Y, Fernandez-del Castillo C. Ten-year experience with 733 pancreatic resections: changing indications, older patients, and decreasing length of hospitalization. Arch Surg 2001;136: 391-398.

3 Jagad RB, Koshariya M, Kawamoto J, Papastratis P, Kefalourous H, Patris V, et al. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: our approach. Hepatogastroenterology 2008;55:275-281.

4 Jones RM, Hardy KJ. The hepatic artery: a reminder of surgical anatomy. J R Coll Surg Edinb 2001;46:168-170.

5 Michels NA. Blood supply and anatomy of the upper abdominal organs with a descriptive atlas. Lippincott, Philad elphia;1955:139-182.

6 Hiatt JR, Gabbay J, Busuttil RW. Surgical anatomy of the hepatic arteries in 1000 cases. Ann Surg 1994;220:50-52.

7 Farnell MB, Nagorney DM, Sarr MG. The Mayo clinic approach to the surgical treatment of adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Surg Clin North Am 2001;81:611-623.

8 Pessaux P, Regenet N, Arnaud JP. Resection of the retroportal pancreatic lamina during a cephalic pancreaticoduodenectomy: first dissection of the superior mesenteric artery. Ann Chir 2003;128:633-636.

9 Whipple AO, Parsons WB, Mullins CR. Whipple AO, Parson WB, Mullins CR. Treatment of carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater. Ann Surg 1935;102:763-779.

10 Kausch W. Das carcinoma der Papilla Duodeni und seine radikale Entfemung: beitrage klinischen. Chirurgie 1912;78:439-486.

11 Leach SD, Davidson BS, Ames FC, Evans DB. Alternative method for exposure of the retropancreatic mesenteric vasculature during total pancreatectomy. J Surg Oncol 1996; 61:163-165.

12 Machado MC, Penteado S, Cunha JE, Jukemura J, Herman P, Bacchella T, et al. Pancreatic head tumors with portal vein involvement: an alternative surgical approach. Hepatogastroenterology 2001;48:1486-1487.

13 Bachellier P, Nakano H, Oussoultzoglou PD, Weber JC, Boudjema K, Wolf PD, et al. Is pancreaticoduodenectomywith mesentericoportal venous resection safe and worthwhile? Am J Surg 2001;182:120-129.

14 Capussotti L, Massucco P, Ribero D, Viganò L, Muratore A, Calgaro M. Extended lymphadenectomy and vein resection for pancreatic head cancer: outcomes and implications for therapy. Arch Surg 2003;138:1316-1322.

15 Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, Sohn TA, Campbell KA, Sauter PK, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with or without distal gastrectomy and extended retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy for periampullary adenocarcinoma, part 2: randomized controlled trial evaluating survival, morbidity, and mortality. Ann Surg 2002;236:355-368.

16 Varty PP, Yamamoto H, Farges O, Belghiti J, Sauvanet A. Early retropancreatic dissection during pancreaticoduodenectomy. Am J Surg 2005;189:488-491.

17 Yang F, Long J, Fu DL, Jin C, Yu XJ, Xu J, et al. Aberrant hepatic artery in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. Pancreatology 2008;8:50-54.

18 Yamamoto S, Kubota K, Rokkaku K, Nemoto T, Sakuma A. Disposal of replaced common hepatic artery coursing within the pancreas during pancreatoduodenectomy: report of a case. Surg Today 2005;35:984-987.

19 Yang SH, Yin YH, Jang JY, Lee SE, Chung JW, Suh KS, et al. Assessment of hepatic arterial anatomy in keeping with preservation of the vasculature while performing pancreatoduodenectomy: an opinion. World J Surg 2007;31: 2384-2391.

20 Traverso LW, Freeny PC. Pancreaticoduodenectomy. The importance of preserving hepatic blood flow to prevent biliary fistula. Am Surg 1989;55:421-426.

21 Lee JM, Lee YJ, Kim CW, Moon KM, Kim MW. Clinical implications of an aberrant right hepatic artery in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Surg 2009;33: 1727-1732.

22 Koops A, Wojciechowski B, Broering DC, Adam G, Krupski-Berdien G. Anatomic variations of the hepatic arteries in 604 selective celiac and superior mesenteric angiographies. Surg Radiol Anat 2004;26:239-244.

23 Koniaris LG, Schoeniger LO, Kovach S, Sitzmann JV. The quick, no-twist, no-kink portal confluence reconstruction. J Am Coll Surg 2003;196:490-494.

24 Fujisaki S, Tomita R, Fukuzawa M. Utility of mobilization of the right colon and the root of the mesentery for avoiding vein grafting during reconstruction of the portal vein. J Am Coll Surg 2001;193:576-578.

25 Popescu I, David L, Dumitra AM, Dorobantu B. The posterior approach in pancreaticoduodenectomy: preliminary results. Hepatogastroenterology 2007;54:921-926.

Received May 22, 2011

Accepted after revision August 18, 2011

If a little knowledge is dangerous, where is a man who has so much as to be out of danger?

—Thomas H. Huxley

Author Affiliations: First Surgical Unit (Lupascu C, Andronic D, Vasiluta C and Vlad N), and Imaging Department (Ursulescu C), "Gr. T. Popa" University of Medicine and Pharmacy Iasi, "St. Spiridon" Hospital, Independentei Bld. 1, 700111 Iasi, Romania

Dan Andronic, MD, PhD, First Surgical Unit, "Gr. T. Popa" University of Medicine and Pharmacy Iasi, "St. Spiridon" Hospital, Independentei Bld. 1, 700111 Iasi, Romania (Tel: 0040-744-820170; Fax: 0040-232-21-82-72; Email: candroni@gmail.com)

© 2011, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(11)60108-2

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Harmine induces apoptosis in HepG2 cells via mitochondrial signaling pathway

- Clinicopathological analysis of 14 patients with combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International (HBPD INT)

- Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver presenting as a hemorrhagic cystic tumor in an adult

- Fulminant liver failure models with subsequent encephalopathy in the mouse

- Risk factors of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in patients with hepatolithiasis: a case-control study