Risk factors of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in patients with hepatolithiasis: a case-control study

2011-07-03ZhenYuLiuYanMingZhouLeHuaShiandZhengFengYin

Zhen-Yu Liu, Yan-Ming Zhou, Le-Hua Shi and Zheng-Feng Yin

Shanghai, China

Risk factors of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in patients with hepatolithiasis: a case-control study

Zhen-Yu Liu, Yan-Ming Zhou, Le-Hua Shi and Zheng-Feng Yin

Shanghai, China

BACKGROUND:Why 3.3% to 10% of all patients with hepatolithiasis develop intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) remains unknown. We carried out a hospital-based case-control study to identify risk factors for the development of ICC in patients with hepatolithiasis in China.

METHODS:Eighty-seven patients with pathologically diagnosed hepatolithiasis associated with ICC and 228 with hepatolithiasis alone matched by sex, age (±2 years), hospital admittance and place of residence were interviewed during the period of 2000-2008. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for each risk factor.

RESULTS:Among the patients with hepatolithiasis associated with ICC, the mean age was 57.7 years and 61.0% were female. Univariate analysis showed that the significant risk factors for ICC development in hepatolithiasis were smoking, family history of cancer, appendectomy during childhood (under age 20), and duration of symptoms >10 years. In multivariate stepwise logistic regression analysis, smoking (OR=1.931, 95% CI: 1.000-3.731), family history of cancer (OR=5.175, 95% CI: 1.216-22.022), and duration of symptoms >10 years (OR=2.348, 95% CI: 1.394-3.952) were independent factors.

CONCLUSION:Smoking, family history of cancer and duration of symptoms >10 years may be risk factors for ICC in patients with hepatolithiasis.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2011; 10: 626-631)

risk factors; intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; hepatolithiasis; case-control study

Introduction

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) is the second most common malignancy after hepatocellular carcinoma among the primary liver cancers, accounting for 3% of all gastrointestinal cancers worldwide.[1]There is a marked regional variation in the incidence of ICC, linked strongly to the distribution of risk factors. Hepatolithiasis is uncommon in Western countries, but is prevalent in East Asia including China, Japan, and Korea because of poor nutritional status and poor sanitation.[2,3]A strong correlation has been reported between hepatolithiasis and ICC.[4-13]However, why 3.3% to 10% of all patients with hepatolithiasis develop ICC remains unknown. The present hospitalbased case-control study was undertaken to identify risk factors for the development of ICC in patients with hepatolithiasis.

Methods

Study population

One hundred and thirty-seven patients diagnosed with hepatolithiasis associated with ICC in Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital, Second Military Medical University (Shanghai, China) between February 2000 and May 2008 were eligible for inclusion. To ensure the inclusion of patients, only those with histologically confirmed ICC were selected and those diagnosed with other cancers within 5 years before the date of ICC diagnosis were excluded. We excluded 33 patients with a clinical diagnosis only, 8 with combined hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma, and 9 who had been diagnosedwith other cancers within 5 years before the diagnosis of ICC. Finally, the remaining 87 patients with histopathologically confirmed ICC were enrolled in this study.

Eligible control subjects were 547 patients with hepatolithiasis alone who underwent hepatectomy in our hospital between 2000 and 2008. We excluded patients diagnosed with cancers or who were missing any data regarding risk factors and cancers. After excluding unsuitable individuals, we identified 228 patients matched with the case group by sex, age (±2 years), and date of admission. This study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and the guidelines of the Ethics Committee of our hospital.

Data collection

Data were obtained by review of the complete medical history collected from patient files. The following data were recorded in a protocol: 1) duration of symptoms; 2) family history of cancer in first-degree relatives; 3) previous biliary surgery and other surgery; 4) other present diseases such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, primary sclerosing cholangitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and liver fluke infection (Clonorchis sinensis or Opisthorchis viverrini); and 5) smoking, alcohol consumption, and exposure to chemicals. We assessed total alcohol intake in grams of ethanol consumed per day (g/day) according to the average ethanol content of wine (12% by volume), beer (5%) and white spirit (40%). An overall measure of lifetime alcohol intake was then calculated. Heavy alcohol consumption was defined as drinking at least 80 g of alcohol per day.[12]A smoker was defined as someone who had smoked 20 cigarettes or more per day for more than 1 year.[14]

Blood samples were taken from all patients in the first morning after hospital admission, and tested for HBsAg and anti-HCV using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA; Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL., USA).

Statistical analysis

Univariate analysis was performed using the Chisquare or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and Student's t test for continuous variables. Variables with a P value of less than 0.05 in the univariate analysis were further tested in a multiple logistic regression analysis using conditional logistic regression. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for each risk factor. All statistical tests were two-sided with a significance level of 0.05. These analyses were performed using SPSS 11.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL., USA).

Results

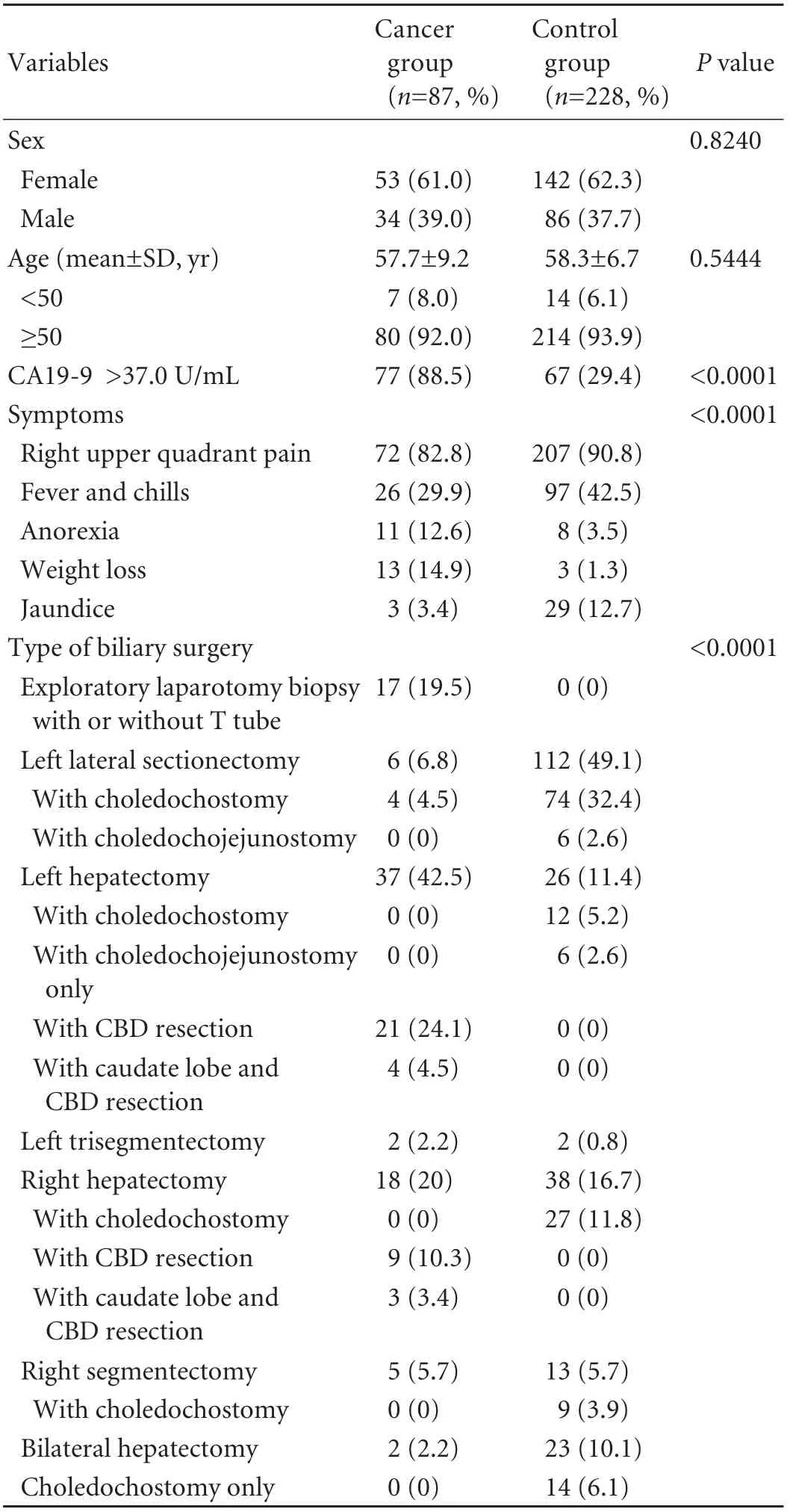

The sex and age distributions of the two groups were similar. Among the cases of hepatolithiasis associated with ICC, the mean age was 57.7 years, and 61.0% were female. With regard to location, the tumor was present in both liver lobes in 8 patients, only in the right lobe in 18, and only in the left lobe in 61. Right upper quadrant pain was the most frequent symptom encountered in the two groups. Anorexia and weight loss occurred morefrequently in the cancer group, whereas fever, chills and jaundice were more common in the control group. In addition, elevated levels of serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9, a glycoprotein tumor marker, with normal limits of 0.0-37.0 U/mL) were found more frequently in the cancer group (Table 1). Six patients in the cancer group had a family history of cancer (gastric cancer, 2; esophageal cancer, 1; breast cancer, 1; lung cancer, 1; hepatocellular carcinoma, 1), and 3 patients in the control group had a family history of cancer (gastric cancer, 1; cervical cancer, 1; bone cancer, 1).

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of cancer and matched control groups

Univariate analysis showed that the significant risk factors for ICC development in hepatolithiasis were smoking, family history of cancer, appendectomy during childhood (under age 20), and duration of symptoms >10 years.

Table 2. Risk factors of ICC in patients with hepatolithiasis: univariate and multivariate logistic regression

In multivariate stepwise logistic regression analysis, smoking (OR=1.931, 95% CI: 1.000-3.731), family history of cancer (OR=5.175, 95% CI: 1.216-22.022), and duration of symptoms >10 years (OR=2.348, 95% CI: 1.394-3.952) were independent factors (Table 2).

The presence of viral hepatitis infection, liver fluke infection, alcohol consumption, previous biliary surgery, location of stones, and other medical conditions such as hypertension or diabetes mellitus were not significantly associated with ICC development (Table 2). None of the patients in either group had primary sclerosing cholangitis and/or inflammatory bowel disease. Because of the small sample size of other types of surgery such as thyroidectomy and gastrectomy in each group, we restricted analysis to larger studies.

Discussion

Several factors have been reported as etiologic factors of ICC including primary sclerosing cholangitis,[15,16]viral hepatitis infection,[12,13,17]and liver fluke infection.[15,18,19]In 1942, Sanes and Maccallum[20]first reported two cases of ICC associated with hepatolithiasis that were discovered incidentally at autopsy. The same phenomenon was reported later by other authors. The incidence of this rare entity ranged from 3.3% to 10% reported in various clinical or autopsy case series of patients with hepatolithiasis.[4-13]On the other hand, hepatolithiasis was found in 5.4% to 65.4% of patients with ICC.[8,10-13]In Italy, a case-control study found that patients with hepatolithiasis had an OR for ICC development of 6.7 (95% CI: 1.3-33.4).[11]Similarly, in a large case-control study from Korea comparing 622 cases of ICC with 2488 healthy controls, 9.8% of cases were found to be associated with hepatolithiasis, compared with 0.2% of the controls. The multivariate analysis showed that hepatolithiasis was associated with ICC (OR=50.0, 95% CI: 21.2-117.3).[12]In our most recent case-control study, the prevalence of hepatolithiasis was 5.4% in cases compared with 1.1% in controls, indicating that hepatolithiasis is an independent risk factor for ICC development.[13]Therefore, there seems to be reasonable epidemiological evidence for a causal association between hepatolithiasis and ICC. However, why 3.3% to 10% of all patients with hepatolithiasis develop ICC remains unknown.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify risk factors for the development of ICC in patients with hepatolithiasis in China, an area with one of the highest incidence rates of hepatolithiasis in the world.[3,21]Our results suggest that smoking is a significant risk factor for ICC in patients with hepatolithiasis. In another study, smoking was shown to be a risk factor for the development of ICC in primary sclerosing cholangitis patients.[22]Given that both hepatolithiasis and primary sclerosing cholangitis are associated with increased risk of ICC, it is possible that, in some people with these risk factors, smoking-induced oxidative stress increases susceptibility to chronic inflammation, DNA damage, and ICC development.

In the present study, we found a five-fold greater risk for ICC in subjects with a positive family history of cancer. Previous studies reported that a positive family history of cancer in first-degree relatives is associated with the risk of developing cancer.[23-25]Such an association could be attributed to common genetic abnormalities (e.g., point mutation, chromosomal loss or gain, and DNA methylation) or environmental factors that may cause genetic alterations in members of the same family and may later predispose healthy family members to develop malignancies.[24]It has been suggested that P16/INK4A genetic hypermethylation is an important event at early stages of the multistep carcinogenesis of ICC arising in hepatolithiasis.[26]

Despite having inconsistent results, some epidemiological studies and clinical observations indicated that appendectomy might predispose to an increased risk of cancer.[27-30]The appendix contains abundant lymphoid tissue that develops during infancy and continues to grow through adolescence and early adulthood. An increasing body of evidence suggests that the appendix is an integral component of the large gut-associated lymphoid tissue that has been recently recognized to play an important role in the immune system.[30]Rabbit experiments showed that neonatal appendectomy impairs mucosal immunity.[31]The complications of hepatolithiasis, recurrent cholangitis, abscess, and jaundice, may weaken the immune system. Appendectomy may enhance this effect, thereby increasing the likelihood of ICC. The present study showed a significant risk associated with appendectomy under univariate analysis, but not under multivariate analysis. Thus, it may be a reinforcing factor but not an independent risk for ICC in patients with hepatolithiasis.

The pathogenic mechanism underlying the relationship of hepatolithiasis to ICC is still unclear. Chronic bacterial infection, bile stasis, and the mechanical irritation of hepatolithiasis can lead to the development of mucosal adenomatous hyperplasia and chronic proliferative cholangitis.[7]Hou et al[32]demonstrated that chronic infestation with Clonorchis sinensis can ultimately induce adenomatous epithelial hyperplasia and cholangiocarcinoma. Duration of symptoms >10 years was the most powerful risk factor for ICC in patients withhepatolithiasis in our study. In addition, most (92.0%) ICC patients with hepatolithiasis were diagnosed after the fifth decade of life. These findings support the hypothesis that longstanding chronic proliferative cholangitis in the presence of hepatolithiasis can induce progressive changes to atypical epithelial hyperplasia, which may develop into malignancy.[4]

Kim et al[33]reported that hepatolithiasis associated with ICC tends to occur in those patients with stones in the right or both lobes of the liver rather than in those with stones in the left lobe only. However, we found that the incidence of ICC was higher in patients with hepatolithiasis of the left lobe. This observation is consistent with previous studies.[10,11]In fact, stones were also located more frequently in the left lobe in our control series, indicating no significant relationship between location of stones and ICC development.

It should be noted that our study also had several potential limitations. This was a hospital-based casecontrol study in a single hospital, not a populationbased study. It is, therefore, possible that a selection bias may have resulted from differential referral patterns. However, in hepatolithiasis patients, it is usually difficult to prove the absence of ICC.[7]To ensure the absence of cancer in our control group, we selected patients in whom the resected specimens were carefully examined following hepatectomy. Therefore, a hospital-based design was appropriate to ascertain the case and control groups.

In conclusion, our results suggest that smoking, family history of cancer, and duration of symptoms >10 years are risk factors for ICC in patients with hepatolithiasis. Future studies are needed to further explore the role of these risk factors.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Contributors:LZY and ZYM participated in the design and coordination of the study, carried out the critical appraisal and the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. SLH and YZF developed the literature search, carried out the extraction of data, assisted in the critical appraisal of included studies and assisted in writing up. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. YZF is the guarantor.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Khan SA, Thomas HC, Davidson BR, Taylor-Robinson SD. Cholangiocarcinoma. Lancet 2005;366:1303-1314.

2 Nakayama F, Soloway RD, Nakama T, Miyazaki K, Ichimiya H, Sheen PC, et al. Hepatolithiasis in East Asia. Retrospective study. Dig Dis Sci 1986;31:21-26.

3 Nakayama F, Koga A, Ichimiya H, Todo S, Shen K, Guo RX, et al. Hepatolithiasis in East Asia: comparison between Japan and China. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1991;6:155-158.

4 Sheen-Chen SM, Chou FF, Eng HL. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in hepatolithiasis: A frequently overlooked disease. J Surg Oncol 1991;47:131-135.

5 Chijiiwa K, Ichimiya H, Kuroki S, Koga A, Nakayama F. Late development of cholangiocarcinoma after the treatment of hepatolithiasis. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1993;177:279-282.

6 Kubo S, Kinoshita H, Hirohashi K, Hamba H. Hepatolithiasis associated with cholangiocarcinoma. World J Surg 1995;19: 637-641.

7 Su CH, Shyr YM, Lui WY, P'Eng FK. Hepatolithiasis associated with cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg 1997;84:969-973.

8 Chen MF, Jan YY, Hwang TL, Jeng LB, Yeh TS. Impact of concomitant hepatolithiasis on patients with peripheral cholangiocarcinoma. Dig Dis Sci 2000;45:312-316.

9 Hur H, Park IY, Sung GY, Lee DS, Kim W, Won JM. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma associated with intrahepatic duct stones. Asian J Surg 2009;32:7-12.

10 Okuda K, Kubo Y, Okazaki N, Arishima T, Hashimoto M. Clinical aspects of intrahepatic bile duct carcinoma including hilar carcinoma: a study of 57 autopsy-proven cases. Cancer 1977;39:232-246.

11 Donato F, Gelatti U, Tagger A, Favret M, Ribero ML, Callea F, et al. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and hepatitis C and B virus infection, alcohol intake, and hepatolithiasis: a casecontrol study in Italy. Cancer Causes Control 2001;12:959-964.

12 Lee TY, Lee SS, Jung SW, Jeon SH, Yun SC, Oh HC, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in Korea: a case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:1716-1720.

13 Zhou YM, Yin ZF, Yang JM, Li B, Shao WY, Xu F, et al. Risk factors for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a case-control study in China. World J Gastroenterol 2008;14:632-635.

14 Hassan MM, Bondy ML, Wolff RA, Abbruzzese JL, Vauthey JN, Pisters PW, et al. Risk factors for pancreatic cancer: casecontrol study. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:2696-2707.

15 Broomé U, Lofberg R, Veress B, Eriksson LS. Primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis: evidence for increased neoplastic potential. Hepatology 1995;22:1404-1408.

16 Bergquist A, Ekbom A, Olsson R, Kornfeldt D, Lööf L, Danielsson A, et al. Hepatic and extrahepatic malignancies in primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol 2002;36:321-327.

17 Shaib YH, El-Serag HB, Davila JA, Morgan R, McGlynn KA. Risk factors of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a case-control study. Gastroenterology 2005;128:620-626.

18 Shin HR, Lee CU, Park HJ, Seol SY, Chung JM, Choi HC, et al. Hepatitis B and C virus, Clonorchis sinensis for the risk of liver cancer: a case-control study in Pusan, Korea. Int J Epidemiol 1996;25:933-940.

19 Parkin DM, Srivatanakul P, Khlat M, Chenvidhya D, Chotiwan P, Insiripong S, et al. Liver cancer in Thailand. I. A case-control study of cholangiocarcinoma. Int J Cancer 1991; 48:323-328.

20 Sanes S, Maccallum JD. Primary carcinoma of the liver:cholangioma in hepatolithiasis. Am J Pathol 1942;18:675-687.

21 Huang ZQ, Huang XQ, Zhang WZ, Xu LN, Yang T, Zhang AQ, et al. Liver resection in hepatolithiasis: 20-year's evolution. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi 2008;46:1450-1452.

22 Bergquist A, Glaumann H, Persson B, Broomé U. Risk factors and clinical presentation of hepatobiliary carcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis: a case-control study. Hepatology 1998;27:311-316.

23 La Vecchia C, Negri E, Franceschi S, Gentile A. Family history and the risk of stomach and colorectal cancer. Cancer 1992;70:50-55.

24 Hassan MM, Phan A, Li D, Dagohoy CG, Leary C, Yao JC. Family history of cancer and associated risk of developing neuroendocrine tumors: a case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2008;17:959-965.

25 Mahdavinia M, Bishehsari F, Ansari R, Norouzbeigi N, Khaleghinejad A, Hormazdi M, et al. Family history of colorectal cancer in Iran. BMC Cancer 2005;5:112.

26 Kuroki T, Tajima Y, Kanematsu T. Hepatolithiasis and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: carcinogenesis based on molecular mechanisms. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2005; 12:463-466.

27 Cassimos C, Sklavunu-Zurukzoglu S, Catriu D, Panajiotidu C. The frequency of tonsillectomy and appendectomy in cancer patients. Cancer 1973;32:1374-1379.

28 Fan YK, Zhang CC. Appendectomy and cancer. An epidemiological evaluation. 1986;99:523-526.

29 Zheng W, Linet MS, Shu XO, Pan RP, Gao YT, Fraumeni JF Jr. Prior medical conditions and the risk of adult leukemia in Shanghai, People's Republic of China. Cancer Causes Control 1993;4:361-368.

30 Cope JU, Askling J, Gridley G, Mohr A, Ekbom A, Nyren O, et al. Appendectomy during childhood and adolescence and the subsequent risk of cancer in Sweden. Pediatrics 2003;111:1343-1350.

31 Dasso JF, Howell MD. Neonatal appendectomy impairs mucosal immunity in rabbits. Cell Immunol 1997;182:29-37.

32 Hou PC. Primary carcinoma of bile duct of the liver of the cat(felis catus) infested with clonorchis sinensis. J Pathol Bacteriol 1964;87:239-244.

33 Kim YT, Byun JS, Kim J, Jang YH, Lee WJ, Ryu JK, et al. Factors predicting concurrent cholangiocarcinomas associated with hepatolithiasis. Hepatogastroenterology 2003;50:8-12.

Received November 11, 2010

Accepted after revision June 1, 2011

Education is the best provision for old age.

—Aristotle

Author Affiliations: Molecular Oncology Laboratory (Liu ZY and Yin ZF) and Department of Comprehensive Treatmenti(Liu ZY and Shi LH), Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai 200438, China; Department of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreato-Vascular Surgery, First Affiliated Hospital, Xiamen University, Xiamen 361003, China (Zhou YM)

Zheng-Feng Yin, MD, PhD, Molecular Oncology Laboratory, Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai 200438, China (Tel: 86-21-81875351; Email: yinzfk@ yahoo.com.cn)

© 2011, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(11)60106-9

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Fulminant liver failure models with subsequent encephalopathy in the mouse

- Relationship between pancreaticobiliary maljunction and gallbladder carcinoma: a meta-analysis

- Harmine induces apoptosis in HepG2 cells via mitochondrial signaling pathway

- Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver presenting as a hemorrhagic cystic tumor in an adult

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International (HBPD INT)

- Clinicopathological analysis of 14 patients with combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma