Polymorphisms of CCL3L1/CCR5 genes and recurrence of hepatitis B in liver transplant recipients

2011-07-03HongLiHaiYangXieLinZhouWeiLinWangTingBoLiangMinZhangandShuSenZheng

Hong Li, Hai-Yang Xie, Lin Zhou, Wei-Lin Wang, Ting-Bo Liang, Min Zhang and Shu-Sen Zheng

Hangzhou, China

Polymorphisms of CCL3L1/CCR5 genes and recurrence of hepatitis B in liver transplant recipients

Hong Li, Hai-Yang Xie, Lin Zhou, Wei-Lin Wang, Ting-Bo Liang, Min Zhang and Shu-Sen Zheng

Hangzhou, China

BACKGROUND:The genetic diversity of chemokines and chemokine receptors has been associated with the outcome of hepatitis B virus infection. The aim of this study was to evaluate whether the copy number variation in the CCL3L1 gene and the polymorphisms of CCR5Δ32 and CCR5-2459A→G (rs1799987) are associated with recurrent hepatitis B in liver transplantation for hepatitis B virus infection-related endstage liver disease.

METHODS:A total of 185 transplant recipients were enrolled in this study. The genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood, the copy number of the CCL3L1 gene was determined by a quantitative real-time PCR based assay, CCR5Δ32 was detected by a sizing PCR method, and a single-nucleotide polymorphism in CCR5-2459 was detected by restriction fragment length polymorphism PCR.

RESULTS:No CCR5Δ32 mutation was detected in any of the individuals from China. Neither copy number variation nor polymorphism in CCR5-2459 was associated with posttransplant re-infection with hepatitis B virus. However, patients with fewer copies (<4) of the CCL3L1 gene compared with the population median in combination with the CCR5G allele had a significantly higher risk for recurrent hepatitis B (odds ratio=1.93, 95% CI: 1.00-3.69;P=0.047).

CONCLUSION:Patients possessing the compound decreased functional genotype of both CCL3L1 and CCR5 genes might be more likely to have recurrence of hepatitis B after transplantation.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2011; 10: 593-598)

CCL3L1; chemokine receptor 5; copy number variation; hepatitis B; liver transplantation

Introduction

Liver transplantation has become an effective method to cure hepatitis B virus (HBV) infectionrelated end-stage liver disease. The prophylactic use of hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) and nucleotide analogous lamivudine (LAM) has greatly decreased the re-infection with HBV after transplantation. However, the incidence of recurrence of hepatitis B is still a risk factor for the prognosis of transplantation.[1]

HBV-specific T-cell-mediated immunity plays an important role in viral clearance in post-transplant reinfection. The interactions between chemokines and chemokine receptors contribute to regulating their activation, proliferation, and migration, thus affecting the ability of leukocytes to accumulate in the target organ and kill HBV-infected hepatic parenchyma cells.[2]Some genetic variants of chemokines and chemokine receptors have been reported to be associated with biological effects, and polymorphisms in these genes could be factors that cause individual differences in the susceptibility to HBV re-infection after transplantation.[3]

CCR5 (MIM: 601373), the C-C motif chemokine receptor, is expressed mainly in granulocytes, macrophages, immature dendritic cells, CD8+lymphocytes, and Th1 lymphocytes.[4]The CCR5Δ32 mutation (a 32-bp deletion) and polymorphism in CCR5-2459A→G (rs1799987) result in functional loss of CCR5. CCL3L1 chemokine (MIM: 601395), the most potent natural ligand for CCR5, is a nonallelic copy of CCL3/MIP-α chemokine. It is a Th1 chemokine that promotes T-cell activation and proliferation by interacting with its receptors. The CCL3L1 gene displays copy number variation (CNV) amongindividuals, and a high copy number up-regulates the expression level of mRNA and the functional chemokine.[5,6]Polymorphisms in these two genes have been associated with viral infections such as HIV and HCV.[7-9]

In theory, polymorphisms in the CCL3L1 and CCR5 genes which are associated with expression level might lead to individual differences in recurrent hepatitis B in liver transplant recipients, by regulating the migration and proliferation of the effective T-cells. In the present study, the CNV in the CCL3L1 gene, polymorphisms in CCR5-2459 and a CCR5Δ32 mutation were assessed in transplant recipients, attempting to estimate the association between polymorphisms in the CCL3L1 and CCR5 genes and the risk of recurrent hepatitis B.

Methods

Patients and clinical characteristics

A total of 185 patients who underwent liver transplantation because of HBV infection were enrolled in this study. The transplants were performed from January 2006 to February 2009 at the Division of Hepatobiliary Pancreatic Surgery, First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine. All the individuals were ethnic Han Chinese. This study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, and consent in written form was obtained from all patients.

The regimen for immunosuppressive therapy and prophylaxis against recurrence of hepatitis B were similar to those described in our previous reports.[10,11]The regimen for the maintenance of immunosuppression consisted of triple therapy with tacrolimus, mycophenolate and prednisone. The dose of tacrolimus was adjusted to maintain a level of 7-10 ng/mL for the first postoperative month and 5-7 ng/mL thereafter. The dose of mycophenolate was 500 mg bid by oral administration. Prednisone was discontinued after 3-6 months. A combined protocol of LAM and HBIG was used as prophylaxis against recurrence of hepatitis B. For the patients with serum positive for HBV-DNA, the LAM was administered at 100 mg per day orally before transplantation, and at the time of operation, 8000 IU of HBIG was administered during the anhepatic phase; in contrast, patients who were serologically HBV-DNA-negative were given 6000 IU. A subsequent 800 IU of intramuscular HBIG was administered daily for the first week, twice a week for the next 3 weeks, and then 800 IU monthly thereafter. When LAM resistance occurred, adefovir was substituted for LAM.

The criteria for diagnosis of HBV recurrence were serological detection of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) or ≥105copies/mL HBV-DNA on two occasions or detection of HBsAg in liver tissue.

Genotyping of CNV in the CCL3L1 gene and polymorphism in the CCR5 gene

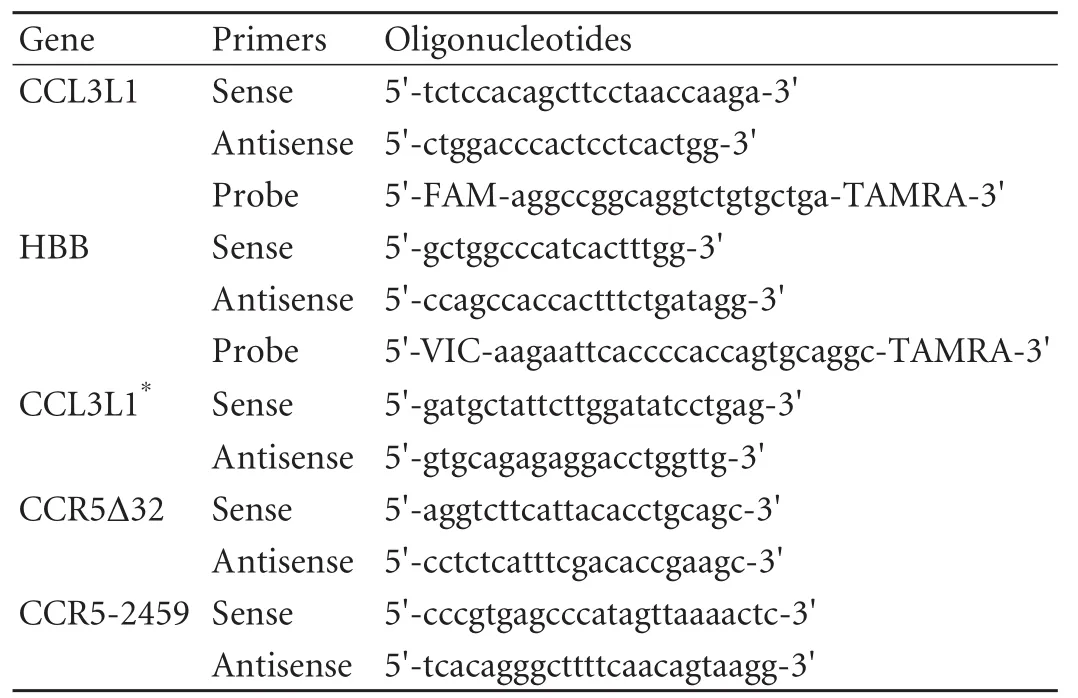

DNA was extracted from whole blood using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The copy number of the CCL3L1 gene was estimated by a TaqMan quantitative real time PCR-based assay as previously described.[6]Real-time PCR was done in the ABI 7500 Fast System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA), with the following universal cycling conditions: 10 minutes at 95 ℃, and 40 cycles of 15 seconds at 95 ℃, and 1 minute at 60 ℃. All samples were tested in duplicate. Standard curves for CCL3L1 and HBB were generated by serial 1:2 (2-64 ng) dilutions of genomic DNA from A431 cells which were shown by Southern blot to possess exactly two copies of the CCL3L1 and HBB genes per diploid genome. The standard plots obtained in real-time PCR assays for CCL3L1 and HBB were very similar, indicating that their amplification efficiencies were similar. Each of the copy numbers of CCL3L1 was taken as two times the ratio of its respective template quantity to that of HBB. Each sample was tested in triplicate. When a sample of 0 copies was obtained, conventional PCR for CCL3L1 was performed to reconfirm the result. The primers and probes are listed in Table 1.

The polymorphism in CCR5-2459 was genotyped using restriction fragment length polymorphism PCR as described previously.[12]Five microliters of the PCR products was digested with 4 units of Bsp1286I (MBIFermentas, Ontario, CA) in a 20 μL volume at 37 ℃for 5 hours using the buffer provided and bovine serum albumin. The digested product was loaded onto a 2% agarose gel, electrophoresed in 1×TBE buffer, and stained with ethidium bromide. CCR532 genotyping was performed using PCR amplification of genomic DNA. The PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on a 3% agarose gel (169bp for the wildtype allele and 137bp for the 32-bp-deletion allele).

Table 1. Primers and probes

To assess the reliability of genotyping, PCR-amplified products were randomly selected and sequenced according to the manufacturer's protocols (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA) using Dye terminator cycle sequencing kits in an ABI PRISM310 genetic analyzer.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL., USA). Quantitative data were shown as mean±SD, continuous variables were analyzed with Student's t test, and the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used for categorical variables. CNV data were shown as mean±SD and were analyzed with Student's t test between the groups. Copy number distributions were compared using non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test. Odds ratios were calculated with conditional logistic regression. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

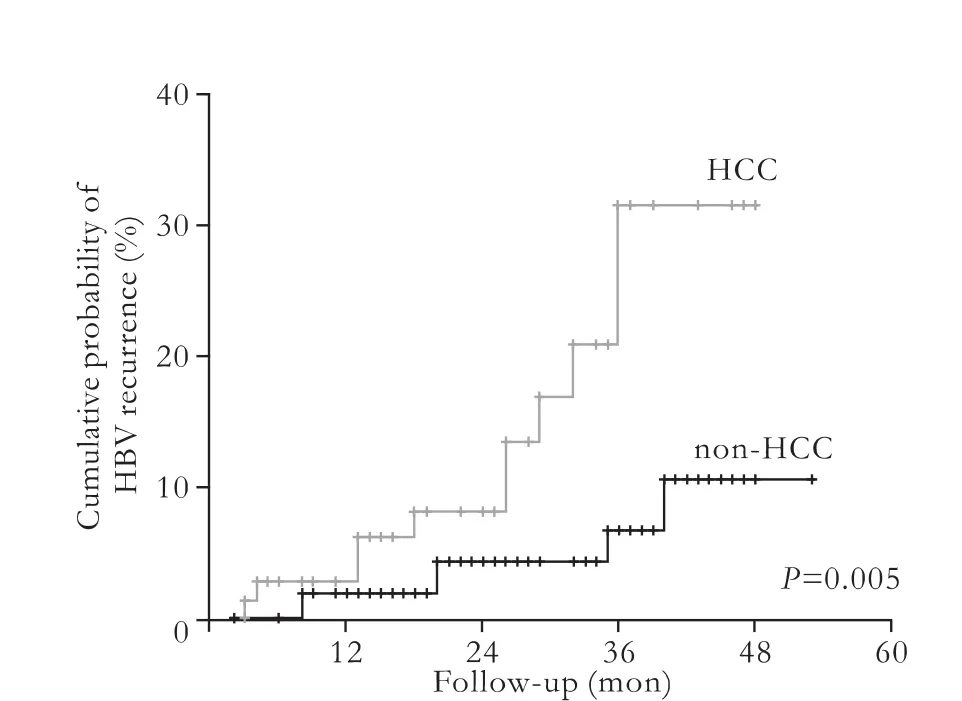

Demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 2. A total of 185 patients (165 males and 20 females) were enrolled, and all the donors were HBcAbnegative. Their mean age was 47.0±11.8 (range 23-70) years. The overall incidence of patients with recurrent hepatitis B was 9.2% (17/185). The mean follow-up time after LT was 26.2±13.8 months. In the present study, primary HCC was associated with HBV recurrence after liver transplantation. As the follow-up time might influence the rate of hepatitis B recurrence, we calculated and plotted the recurrence of HBV by the Kaplan-Meier method (Fig.). The results were consistent with those of previous studies on the relationship between hepatitis B recurrence and hepatocellular carcinoma.[13,14]The other pre-operative characteristics, gender, age, pre-operation DNA level, and HBeAg status showed no differences between the recurrent and non-recurrent groups.

No correlation between CNV and recurrence of hepatitis B

Table 2. Clinical characteristics of patients

Fig. Cumulative probabilities of HBV recurrence. HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma.

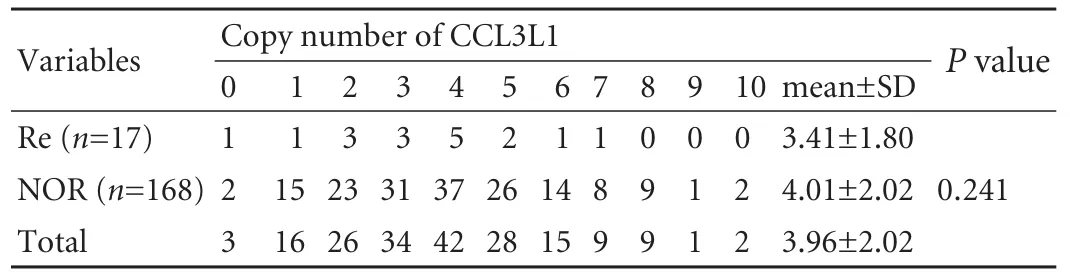

The distributions of CCL3L1 in the patients are listed in Table 3. The CCL3L1 copy number ranged from 0 to 10, and the population median was 4 copies. The majority of the study population carried 2-5 copies. The mean copy number was 3.96±2.02. The mean copy numbers in recurrent and non-recurrent recipients were 3.41±1.80 and 4.01±20.2 (t test, P=0.241). The copy number distribution was shifted to lower values in patients with recurrent hepatitis B, but there was no statistically significant difference (Mann-Whitney U test, P=0.304). We then chose the population median copynumber 4 as the cut-off to divide the patients into two groups (≥4 and <4). The patients who carried the higher numbers of copies of CCL3L1 did not show a higher risk of recurrent hepatitis B (P=0.703).

Table 3. CCL3L1 copy number distributions in transplant recipients

Table 4. Allelic frequencies of CCR5-2459 in transplant recipients

Table 5. Compound CCL3L1 CNV and CCR5-2459 allelic distribution in transplant recipients

No correlation between polymorphism in CCR5-2459 and recurrence of hepatitis B

In the present study, no CCR5Δ32 mutation was detected as it was found in another Chinese cohort.[15]So this mutation was excluded from the next step of analysis. The allelic distributions of CCR5-2459 are listed in Table 4, and no associations were detected between hepatitis B recurrence and polymorphism in CCR5-2459.

The number of CCL3L1 copies lower than the population median in combination with the CCR5-2459G allele was a risk factor for recurrence of hepatitis B.

For further analysis, the patients were classified into 4 groups (Table 5) according to the number of CCL3L1 copies in combination with the CCR5-2459 allele. The groups were as follows: 1) CCL3L1≥4*CCR5A allele; 2) CCL3L1<4*CCR5A allele; 3) CCL3L1≥4*CCR5G allele; and 4) CCL3L1<4*CCR5G allele. Obviously the copy number of CCL3L1 lower than the population median in combination with the CCR5-2459G allele had a higher risk of recurrence of hepatitis B (odds ratio=1.93, 95% CI: 1.00-3.69, P=0.047).

Discussion

The present study is the first to determine the associations between the genotype of the CCL3L1/ CCR5 axis and recurrence of hepatitis B in liver transplantation for HBV infection-related end-stage liver disease. The results suggest that the number of copies (<4) of CCL3L1 fewer than the population median in combination with the CCR5-2459 G allele correlated with decreased expression is a risk of hepatitis B recurrence after liver transplantation.

The host HBV-specific cellular immune response is considered to play an important role in the pathogenesis and progression of HBV infection and viral reactivation. Compared with patients who recovered from HBV infection spontaneously, those with chronic HBV infection show weak and narrowly-directed virusspecific cellular immunity. The lack of cellular immunity is considered to be a major reason for the failure of viral clearance.[16]The HBV-specific T-cellular immunity in liver transplant recipients with recurrence of hepatitis B is not significantly different from that in individuals with chronic hepatitis B,[17]which might be responsible for the recurrence of hepatitis B after transplantation. Chemokine and chemokine receptor interactions are likely to be important in chronic viral hepatitis, where T-cells are recruited to the liver parenchyma to mediate the clearance of hepatocytes infected with virus.[18]Therefore, it is likely that in viral hepatitis, chemokines cause the accumulation and activation of leukocytes in tissues. Hence interactions between chemokines and their receptors might also be responsible for recurrence of hepatitis B after liver transplantation.

CCR5 has been strongly associated with the outcome of HCV infection. CCR5 interacts with its ligands expressed in the liver to promote the recruitment of Th1-expressing cells into the liver to mediate the clearance of HCV-infected hepatocytes.[2]Effective antiviral therapy with IFN-α-containing regimens has been considered to partially up-regulate CCR5 expression in T-cells during HCV infection.[19]CCR5Δ32 causes null function ofthe CCR5 gene, and CCR5-2459A→G in the promoter region is linked to decreased surface expression. Both of these genetic variants are associated with recovery from HBV infection. However, the results are controversial. Thio[20]reported that CCR5Δ32 is a protective genetic factor against HBV infection, and a Korean study[21]demonstrated that CCR5-2459G is associated with spontaneous recovery from HBV infection. However Thio's later report[9]and another study on a Korean cohort[22]indicated that these two genetic variants of CCR5 with low function are not associated with recovery from HBV infection. In addition, Thio et al[9]then proposed a compound genotype, CCR5Δ32*CCL5-403A, as a protective genetic factor against HBV infection. In the present study, CCR5Δ32 was not detected in any individuals, indicating that CCR5Δ32 is totally absent from ethnic Han Chinese populations, so we were unable to analyze associations between CCR5Δ32 and hepatitis B recurrence. Moreover, there was no association between the single nucleoticle polymorphism (SNP) in CCR5-2459 and recurrence of hepatitis B. These results are similar to those from another Chinese cohort.[15]

A CNV is defined as a DNA segment larger than 1kb that involves either microscopic or submicroscopic gains or losses of genomic DNA. CNV is considered to reflect novel genetic diversity in humans, and is widespread among normal individuals. Variation in copy number can influence the transcription or translation of overlapping or nearby genes.[23]Recently, studies have demonstrated that some types of CNV are associated with the pathogenesis, progression and prognosis of diseases,[24]such as systemic lupus erythematosus,[25]rheumatoid arthritis,[26]viral infection, and transplant rejection.[27]The CCL3L1 gene displays CNV among individuals; a quantitative real time PCR based assay has been developed and is considered a reliable method to detect the copy number of the CCL3L1 gene.[28,29]In our study, the CCL3L1 copy number was slightly lower in patients with recurrent hepatitis B than in those with non-recurrence, but the difference was not statistically significant.

For further analysis, the associations between the combined genotypes of CNV in CCL3L1, the SNP in CCR5-2459 and the recurrence of hepatitis B were estimated. The results showed that the genotype of both genes with lower function (<4CCL3L1*CCR5-2459G) was a risk for recurrence of hepatitis B after transplantation. This result suggested that the pathogenesis and progress of HBV infection is affected by multiple and possibly interactive genes. Polymorphism in a single gene, CCL3L1 or CCR5, might not play a role in the recurrence of hepatitis B, but genetic effects would result when the genes occurred together. However, this result is somewhat in conflict with Thio's report,[9]which proposed a combined null functional genotype of CCR5Δ32 and an excessive genotype CCL5-403A as the protective genetic factor against HBV infection in spontaneous recovery of individuals. Apart from racial differences, the following reasons might contribute to the difference in results: 1) a difference in biological effect between the null function genotype and the lower function genotype in CCR5. The biological effect of deficient CCR5 might be compensated for and overwhelmed by other chemokine receptors, such as CCR1;[30]2) all the recipients needed immunosuppressive and prophylactic anti-viral therapy after transplantation, which might change the immune response of the host; and 3) although the resection of explanted liver removed the major viral load, and prophylactic anti-vial therapy inhibited the recurrence of hepatitis B, sensitive PCR can also detect HBV-DNA in serum, peripheral blood mononuclear cell or liver specimens from liver transplant patients who were seronegative for HBsAg and with normal graft function.[31]These factors suggest that the recurrence of hepatitis B after transplantation might be a little different from HBV persisting in patients with chronic viral hepatitis.

In conclusion, the results of the present study suggested that CCL3L1/CCR5 might be an effective target to modulate the immune response of transplant recipients. When a recipient with <4CCL3L1*CCR5-2459G is identified, besides prophylactic anti-viral therapy, an additional modulation of the function of the CCL3L1/ CCR5 axis might be necessary to inhibit the recurrence of hepatitis B after transplantation. The limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size of individuals with recurrent hepatitis B. In the future, more functional data are needed to support the findings in this study.

Funding:This study was supported by grants from the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program) (2009CB522403) and the National S&T Major Project (2008ZX10002-026).

Ethical approval:This study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, China.

Contributors:ZSS proposed the study. LH wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts. ZSS is the guarantor.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Papatheodoridis GV, Cholongitas E, Archimandritis AJ, Burroughs AK. Current management of hepatitis B virus infection before and after liver transplantation. Liver Int 2009;29:1294-1305.

2 Ajuebor MN, Carey JA, Swain MG. CCR5 in T cell-mediated liver diseases: what's going on? J Immunol 2006;177:2039-2045.

3 Colobran R, Pujol-Borrell R, Armengol MP, Juan M. The chemokine network. II. On how polymorphisms and alternative splicing increase the number of molecular species and configure intricate patterns of disease susceptibility. Clin Exp Immunol 2007;150:1-12.

4 Alkhatib G. The biology of CCR5 and CXCR4. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2009;4:96-103.

5 Townson JR, Barcellos LF, Nibbs RJ. Gene copy number regulates the production of the human chemokine CCL3-L1. Eur J Immunol 2002;32:3016-3026.

6 Gonzalez E, Kulkarni H, Bolivar H, Mangano A, Sanchez R, Catano G, et al. The influence of CCL3L1 gene-containing segmental duplications on HIV-1/AIDS susceptibility. Science 2005;307:1434-1440.

7 Bhattacharya T, Stanton J, Kim EY, Kunstman KJ, Phair JP, Jacobson LP, et al. CCL3L1 and HIV/AIDS susceptibility. Nat Med 2009;15:1112-1115.

8 Grünhage F, Nattermann J, Gressner OA, Wasmuth HE, Hellerbrand C, Sauerbruch T, et al. Lower copy numbers of the chemokine CCL3L1 gene in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol 2010;52:153-159.

9 Thio CL, Astemborski J, Thomas R, Mosbruger T, Witt MD, Goedert JJ, et al. Interaction between RANTES promoter variant and CCR5Delta32 favors recovery from hepatitis B. J Immunol 2008;181:7944-7947.

10 Zheng S, Chen Y, Liang T, Lu A, Wang W, Shen Y, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B recurrence after liver transplantation using lamivudine or lamivudine combined with hepatitis B Immunoglobulin prophylaxis. Liver Transpl 2006; 12:253-258.

11 Jiang Z, Feng X, Zhang W, Gao F, Ling Q, Zhou L, et al. Recipient cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 +49 G/G genotype is associated with reduced incidence of hepatitis B virus recurrence after liver transplantation among Chinese patients. Liver Int 2007;27:1202-1208.

12 McDermott DH, Zimmerman PA, Guignard F, Kleeberger CA, Leitman SF, Murphy PM. CCR5 promoter polymorphism and HIV-1 disease progression. Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS). Lancet 1998;352:866-870.

13 Chun J, Kim W, Kim BG, Lee KL, Suh KS, Yi NJ, et al. High viremia, prolonged Lamivudine therapy and recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma predict posttransplant hepatitis B recurrence. Am J Transplant 2010;10:1649-1659.

14 Faria LC, Gigou M, Roque-Afonso AM, Sebagh M, Roche B, Fallot G, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with an increased risk of hepatitis B virus recurrence after liver transplantation. Gastroenterology 2008;134:1890-1899; quiz 2155.

15 Chen DQ, Zeng Y, Zhou J, Yang L, Jiang S, Huang JD, et al. Association of candidate susceptible loci with chronic infection with hepatitis B virus in a Chinese population. J Med Virol 2010;82:371-378.

16 Webster GJ, Reignat S, Brown D, Ogg GS, Jones L, Seneviratne SL, et al. Longitudinal analysis of CD8+T cells specific for structural and nonstructural hepatitis B virus proteins in patients with chronic hepatitis B: implications for immunotherapy. J Virol 2004;78:5707-5719.

17 Luo Y, Lo CM, Cheung CK, Lau GK, Wong J. Hepatitis B virus-specific CD4 T cell immunity after liver transplantation for chronic hepatitis B. Liver Transpl 2009;15:292-299.

18 Wald O, Weiss ID, Galun E, Peled A. Chemokines in hepatitis C virus infection: pathogenesis, prognosis and therapeutics. Cytokine 2007;39:50-62.

19 Yang YF, Tomura M, Iwasaki M, Ono S, Zou JP, Uno K, et al. IFN-alpha acts on T-cell receptor-triggered human peripheral leukocytes to up-regulate CCR5 expression on CD4+and CD8+T cells. J Clin Immunol 2001;21:402-409.

20 Thio CL, Astemborski J, Bashirova A, Mosbruger T, Greer S, Witt MD, et al. Genetic protection against hepatitis B virus conferred by CCR5Delta32: Evidence that CCR5 contributes to viral persistence. J Virol 2007;81:441-445.

21 Ahn SH, Kim do Y, Chang HY, Hong SP, Shin JS, Kim YS, et al. Association of genetic variations in CCR5 and its ligand, RANTES with clearance of hepatitis B virus in Korea. J Med Virol 2006;78:1564-1571.

22 Cheong JY, Cho SW, Choi JY, Lee JA, Kim MH, Lee JE, et al. RANTES, MCP-1, CCR2, CCR5, CXCR1 and CXCR4 gene polymorphisms are not associated with the outcome of hepatitis B virus infection: results from a large scale single ethnic population. J Korean Med Sci 2007;22:529-535.

23 Stranger BE, Forrest MS, Dunning M, Ingle CE, Beazley C, Thorne N, et al. Relative impact of nucleotide and copy number variation on gene expression phenotypes. Science 2007;315:848-853.

24 Zhang F, Gu W, Hurles ME, Lupski JR. Copy number variation in human health, disease, and evolution. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2009;10:451-481.

25 Willcocks LC, Lyons PA, Clatworthy MR, Robinson JI, Yang W, Newland SA, et al. Copy number of FCGR3B, which is associated with systemic lupus erythematosus, correlates with protein expression and immune complex uptake. J Exp Med 2008;205:1573-1582.

26 McKinney C, Merriman ME, Chapman PT, Gow PJ, Harrison AA, Highton J, et al. Evidence for an influence of chemokine ligand 3-like 1 (CCL3L1) gene copy number on susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:409-413.

27 Colobran R, Casamitjana N, Roman A, Faner R, Pedrosa E, Arostegui JI, et al. Copy number variation in the CCL4L gene is associated with susceptibility to acute rejection in lung transplantation. Genes Immun 2009;10:254-259.

28 Field SF, Howson JM, Maier LM, Walker S, Walker NM, Smyth DJ, et al. Experimental aspects of copy number variant assays at CCL3L1. Nat Med 2009;15:1115-1117.

29 He W, Kulkarni H, Castiblanco J, Shimizu C, Aluyen U, Maldonado R, et al. Reply to: "Experimental aspects of copy number variant assays at CCL3L1". Nat Med 2009;15:1117-1120.

30 Ajuebor MN, Wondimu Z, Hogaboam CM, Le T, Proudfoot AE, Swain MG. CCR5 deficiency drives enhanced natural killer cell trafficking to and activation within the liver in murine T cell-mediated hepatitis. Am J Pathol 2007;170: 1975-1988.

31 Naoumov NV, Lopes AR, Burra P, Caccamo L, Iemmolo RM, de Man RA, et al. Randomized trial of lamivudine versus hepatitis B immunoglobulin for long-term prophylaxis of hepatitis B recurrence after liver transplantation. J Hepatol 2001;34:888-894.

Received March 18, 2011

Accepted after revision July 19, 2011

Author Affiliations: Key Laboratory of Combined Multi-Organ Transplantation, Ministry of Public Health (Li H, Xie HY, Zhouland Zheng SS), and Division of Hepatobiliary Pancreatic Surgery (Wang WL, Liang TB, Zhang M and Zheng SS), First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310003, China

Shu-Sen Zheng, MD, PhD, FACS, Key Laboratory of Combined Multi-Organ Transplantation, Ministry of Public Health, Division of Hepatobiliary Pancreatic Surgery, First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310003, China (Tel: 86-571-87236570; Fax: 86-571-87236628; Email: shusenzheng@zju.edu.cn)

© 2011, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(11)60101-X

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Harmine induces apoptosis in HepG2 cells via mitochondrial signaling pathway

- Clinicopathological analysis of 14 patients with combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International (HBPD INT)

- Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver presenting as a hemorrhagic cystic tumor in an adult

- Fulminant liver failure models with subsequent encephalopathy in the mouse

- Risk factors of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in patients with hepatolithiasis: a case-control study