Comparatively lower postoperative hepatolithiasis risk with hepaticocholedochostomy versus hepaticojejunostomy

2010-12-14XiaoJinZhangYiJiangXuWangFuZhouTianandLiZhiLv

Xiao-Jin Zhang, Yi Jiang, Xu Wang, Fu-Zhou Tian and Li-Zhi Lv

Fuzhou, China

Comparatively lower postoperative hepatolithiasis risk with hepaticocholedochostomy versus hepaticojejunostomy

Xiao-Jin Zhang, Yi Jiang, Xu Wang, Fu-Zhou Tian and Li-Zhi Lv

Fuzhou, China

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2010; 9: 38-43)

hepatocholangioplasty;cholangiojejunostomy;hepatolithiasis;gallstones;biliary reconstruction;hepaticocholedochostomy

Introduction

Hepatolithiasis is usually complicated with biliary stricture, and the incidence is 24.3%-41.9%.[1]Postoperative hepatolithiasis recurrence is a dif fi cult problem in the fi eld of biliary tract surgery.Undoubtedly, surgical technique plays an important role in preventing recurrence.[2,3]Hepatic lobectomy and segmentectomy can eliminate the focus ef fi ciently,which is favorable for preventing recurrence.[4]Usually,choledochojejunostomy was employed to drain fl uids in patients with hepatolithiasis complicated with intrahepatic biliary stricture after partial hepatectomy and hilar cholangioplasty.[5]Sphincter of Oddi (SO) loss,biliary re fl ux, and gastrointestinal physiological function disorder often occur after traditional choledochojejuno stomy.[6,7]Therefore, SO maintenance is a controversial issue.[8,9]Tian et al[10]developed subcutaneous tunnel and hepatocholangioplasty using the gallbladder (STHG)technique and applied it in hepatolithiasis patients who had an approximately normal gallbladder andSO. By this surgical technique, an anastomotic channel between the normal gallbladder and the hepatic duct was established to resolve stenosis of the bile duct.Meanwhile, the bottom of the gallbladder was sutured down to the abdominal wall as a reserve channel. As a new technique, the ef fi cacy of STHG is disputable.[11,12]To investigate the effects of hepatocholangioplasty (HC)and hepaticojejunostomy (HJ) on the biliary system, we established canine models for HC and HJ and compared the changes in bile components near the anastomosis,attempting to provide an experimental guide for choosing an alternative schedule for the treatment of hepatolithiasis in the clinic.

MethodsExperimental animals and grouping

Twenty-nine healthy adult hybrid dogs (males and females) weighing 13.6-18.5 kg were provided by the Experimental Animal Center of Fujian Medical University (Fuzhou, China). The animals were given standard food and water and received anti-worm therapy.All the experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of Fujian Province. The dogs were randomly separated into two groups: control group(5 dogs) and obstruction group (24 dogs). The animals in the obstruction group were randomly divided into HC and HJ groups (12/group) at 7 weeks. Then, HC and HJ were performed on the animals in each model subgroup. Of the dogs that received HC, 11 survived,and they were divided into two groups: one month after HC (HC-1 m) group (5 dogs) and fi ve months after HC(HC-5 m) group (6 dogs). Of the dogs that received HJ,10 survived, and they were separated into two groups:one month after HJ (HJ-1 m) group and fi ve months after HJ (HJ-5 m) group (5/group). Sham-operation was performed on dogs in the control group. There was no statistical difference in exposure factors among the groups (P>0.05).

Establishment of animal model[13]

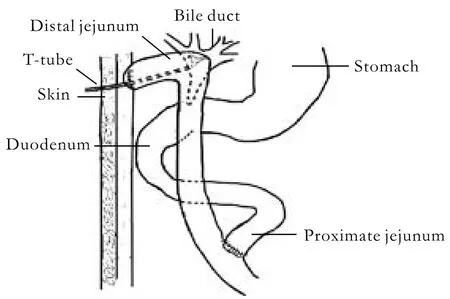

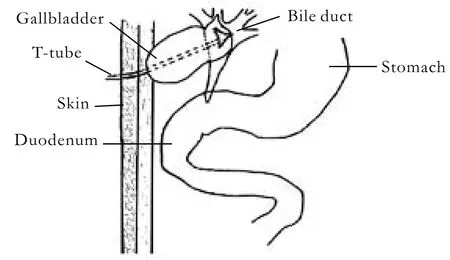

The operations were performed in the following steps: First, an animal model for stenosis of the common bile duct (CBD) under asepsis was established.Dogs in the obstruction group were anesthetized by intravenous pentobarbital sodium (30 mg/kg) injection.The abdominal wall was opened by a vertical incision of approximately 6 cm. The CBD was separated slightly,and a single silk suture was threaded without ligature.The intestinal wall was opened to 2-3 cm from the border of the duodenal mesentery. A 1-cm-long catheter(external diameter 2.0 mm, internal diameter 0.5 mm) was introduced into the CBD via the duodenal papilla. The silk suture was ligated to mimic stenosis of the bile duct. Then, the duodenal wall was sutured transversely, and the abdomen was closed layer by layer.The process in the control group was the same as in the obstruction group except that no indwelling catheter was placed in the CBD. Second, animal models for HC and HJ in dogs were established. The operations were performed at 7 weeks after partial obstruction of the bile duct. The choledochal duct and bile ducts were generally expanded, and the gallbladder was clearly enlarged. The indwelling catheters were removed, and Roux-en-Y HJ or HC was performed. Roux-en-Y HJ was performed with the following steps. After removal of the gallbladder, the jejunum was cut off at 15 cm below the suspensory ligament of the duodenum. Then, it was closed to the distal end and held up. Side-to-side anastomosis was performed between 5 cm from the sutured intestinal canal and the expanded common hepatic duct (CHD). End-to-side anastomosis was performed between the proximal and distal jejunum(40 cm from the biliointestinal anastomosis). A T-tube(O Dia: 0.5-0.6 cm) was internally installed at the biliointestinal anastomosis, and the end was elicited subcutaneously from the jejunum loop (Fig. 1). HC was done by side-to-side anastomosis between the expanded CHD and the caudomedial part of the neck of the gallbladder. A T-tube (O Dia: 0.5-0.6 cm) was installed in the CHD, and the end was elicited from the fundus of the gallbladder (Fig. 2). In the control group, the shamoperation consisted only of anesthesia and opening and closing of the abdominal cavity. Fluid infusion and antiinfection measures were adopted after the operation.The abdominal cavity drainage tube and the T-tube were removed at 3-7 days or 14-18 days after the operation depending on the abdominal cavity drainage.

Sample collection

Samples from the control and obstruction groups were collected during the second operation. Five animals were selected randomly from the 24 in the obstruction group and bile samples were collected. Samples from the HC and HJ groups were collected at 1 month and 5 months after the operation. The techniques were performed again at the corresponding observation times.The abdomen was opened, and internal tube drainage was employed to collect 3 ml of bile. A 1 ml aliquot was used for bacterial culture. Another 2 ml was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4 ℃. The supernatant was collected and stored at -70 ℃ until use.

Measurement of related indices and methods

Total bile acid (TBA) was assayed by phosphomolybdic acid chromatometry. Total bilirubin (TBil)and unconjugated bilirubin (UCB) were determined by diazo assay. Cholesterol (Ch) production was measured by the improved lipid research clinics method;phospholipid (PHL) level was detected by the antiscorbic acid method. Calcium ion concentration was assayed by selective electrode direct determination. Mucin level was assayed using phosphotungstic acid-phenol reagent.Biliary superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was measured by xanthine oxidase assay. Lipid peroxidation(LPO) was determined by thiobarbituric acid.

Broth bouillon was inoculated with 5%-10% bile(v/v) to prepare enrichment broth. Then, it was cultured in an aerobic atmosphere at 35 ℃. Once the enrichment broth became turbid, a blood agar plate was inoculated with some of the broth. If there was no bacterial growth on the plate at 3 days after the inoculation, then the bile was considered negative for aerobic bacteria. Otherwise,it was considered positive. Meanwhile, an anaerobic blood agar plate was inoculated with bile and kept at 35 ℃. The presence or absence of bacterial growth was determined at 72 hours after the inoculation.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean±SD. SPSS11.0 software was employed to analyze the data. Student's t test was used to determine the differences among the groups.One-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine the differences among the groups. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically signi fi cant.

ResultsGeneral status of animals after operation

After the fi rst operation, the 24 animals recovered successfully. Infection of the incisional wound only occurred in 2 animals and they were cured at 18 and 24 days after the operation by changing dressings. All the animals recovered to a normal diet, whereas deep yellow urine appeared at 25-40 days after the fi rst operation.After the second operation, 1 of 12 dogs undergoing the HC technique died from bile leakage, and 3 suffered from infection of the incisional wound. Two of 12 animals undergoing the HJ technique died, 1 of intraabdominal hemorrhage on the 3rd day post-operation,and 1 of anastomotic bile leakage on the 7th day.Infection of the incisional wound occurred in 5 animals,including the one with bile leakage.

Changes in hepatic duct bile components after obstruction

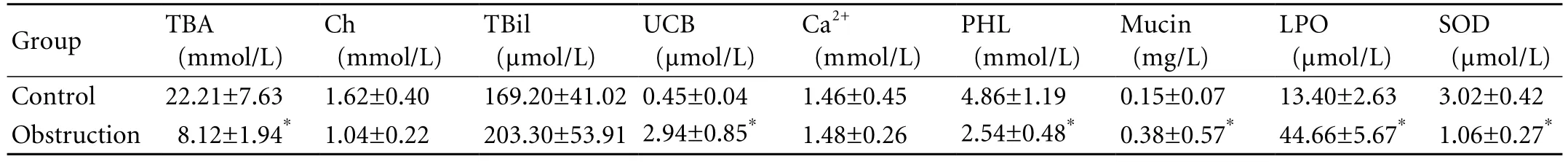

TBA, PHL, and SOD in the drained bile were decreased signi fi cantly at 7 weeks after the obstruction.Although the level of Ch also decreased, the decrease was not statistically signi fi cant. The levels of UCB, mucin,and LPO increased remarkably, and the differences were statistically signi fi cant. No signi fi cant differences were seen in TBil and Ca2+(Table 1).

Changes and comparison of bile components after relief of obstruction by the two techniques

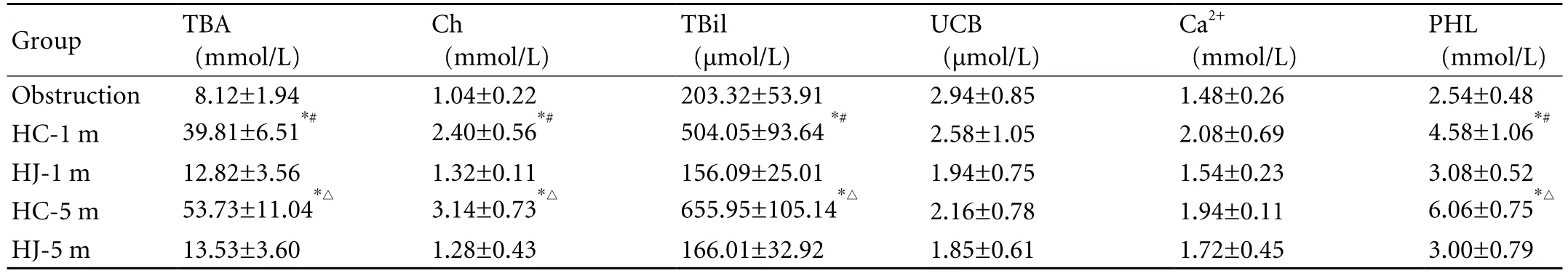

Compared to the model group, TBA, Ch, TBil, and PHL in the HC groups increased signi fi cantly and no signi fi cant difference was seen in the UCB and Ca2+. At 1 month and 5 months postoperatively, the levels of TBA,Ch, TBil, and PHL in the HC group were signi fi cantly higher than those in the HJ group. No signi fi cant difference among the groups was seen in UCB and Ca2+.Compared with HC-1 m, TBA, Ch, Tbil, and PHL in HC-5 m increased signi fi cantly. There was no signi fi cant difference among the groups in UCB and Ca2+. There was no signi fi cant difference in bile components between the HJ-1 m and HJ-5 m groups (Table 2).

Table 1. Comparison of bile components before and after obstruction (mean±SD, n=5)

Table 2. Comparison of bile components before and after relief of obstruction by the two techniques (mean±SD)

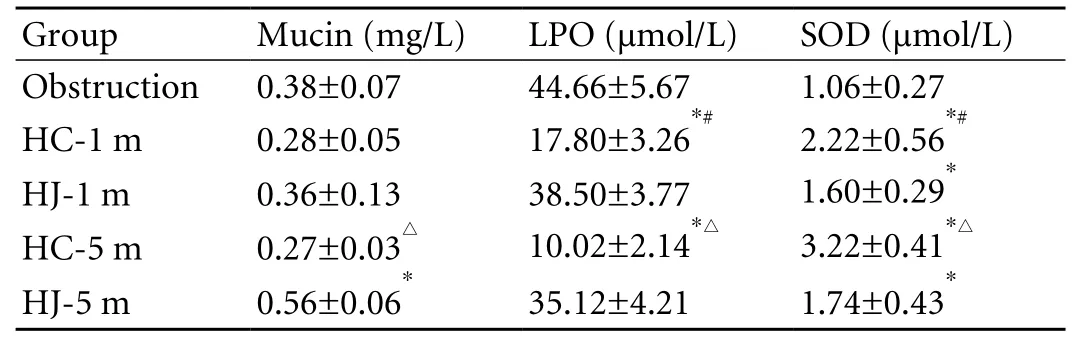

Table 3. Comparison of bile components before and after relief of obstruction by the two techniques (mean±SD)

Changes of mucin protein and oxygen free radicals in bile from hepatic duct after relief of obstruction by the two techniques

There was no signi fi cant difference in mucin protein in bile at 1 month after the operation. The mucin in the HC group was clearly lower than that in the HJ group at 5 months, and the difference was signi fi cant. The LPO in bile in the HC group was remarkably lower than that in the HJ group at 1 month and 5 months after the operation (Table 3).

Bacterial culture

The positive rate for bacteria in bile from the hepatic duct in the control group, the HC group, and the HJ group was 0 (0/5), 40% (2/5) and 100% (5/5) at 1 month after the operation, respectively. The positive rate for bacteria in the HC and HJ groups was 0 (0/6) and 100% (5/5) at 5 months after the operation, respectively.A signi fi cant difference was shown by exact probability assay.

Discussion

To con fi rm which biliary component changes are useful in preventing gallstone formation after the two biliary reconstruction operations, we must understand which biliary components are important in the process of gallstone formation. It has been con fi rmed that gallstone occurrence and recurrence are due to obstruction and infection of the biliary tract. Studies suggest that supersaturable calcium bilirubinate precipitates in bile when the product of Ca2+and bivalent or monovalent anions is more than the solubility product constant(KSP), which is one of the necessary conditions for bile pigment gallstone formation.[14]The following changes may affect the supersaturation and precipitation of calcium bilirubinate. First, any increase of Ca2+and bivalent or monovalent anions will contribute to anion levels above the KSP.[15,16]Second, free radical generation and enhancement of bile will decrease the KSP, which results in deposition of calcium bilirubinate.[17,18]Third,bile acid (BA) can increase the solubility by interfering with hydrogen bond formation in UCB,[19]and the effect occurs in a dose-dependent manner. In addition, BA can decrease free Ca2+levels by forming a soluble compound with Ca2+. Fourth, the pH of bile is also an important factor in regulating the solubility of calcium bilirubinate.Slight reduction in pH can greatly decrease bilirubin anions and shift the balance toward bilirubin molecules,which can dissolve in BA.[15]Fifth, excessive secretion of mucin from the bile duct facilitates the accumulation of calcium bilirubinate. Also, excessive mucin can precipitate with calcium bilirubinate and prevent the formed calcium bilirubinate from redissolving.[20]

In the present study, we arti fi cially induced stricture of the bile duct in dogs and then employed HC and HJ to simulate the therapy for hepatolithiasis complicated with intrahepatic biliary stricture that is used in the clinic.Meanwhile, we measured factors associated with the formation of biliary hepatolithiasis, BA, Ca2+, UCB, mucin,oxygen free radicals, and bacterial growth in bile taken near the anastomosis after the two surgical techniques.We found that the level of TBA in bile in the HC group was signi fi cantly higher than that in the HJ group at the corresponding time. No signi fi cant differences among the groups were seen in UCB and Ca2+. The level of mucin in the HJ group increased gradually, which was clearly higher than that in the HC group at 5 months after the operation.The LPO after HC was signi fi cantly lower than that in the HJ group at the corresponding time. Furthermore, the level of SOD was remarkably higher than that in the HJ group at the corresponding time. The results showed that the level of TBA in the HC group was signi fi cantly higher than that in the HJ group. Moreover, the levels of oxygen free radicals and mucin that promote hepatolithiasis formation were higher than those in the HJ group. There were no signi fi cant differences among the groups in the other hepatolithiasis-related factors, UCB and Ca2+. These results suggest that the changes in biliary components occurring in bile near the anastomosis after HC might be more favorable for preventing biliary hepatolithiasis formation than those seen in bile after HJ.

The HC technique provided adequate transport for the bile duct and gallbladder. Concentrated bile in the gallbladder could exchange with the bile in the porta hepatis at any time, which retained the concentrating and absorptive functions of the gallbladder. The level of TBA was enhanced more signi fi cantly than that of Ch,TBil, PHL, and Ca2+respectively after the HJ technique,and this technique is more useful for preventing biliary supersaturation and precipitation. The absorptive ability of the gallbladder mucosa is the most powerful of all epithelial tissues. In addition to concentrating organic solutes by reabsorbing water and inorganic electrolytes,the gallbladder mucosa can also absorb liposoluble substances such as free Ch, PHL, UCB, and free BA.[19]Ginanni Corradini et al[21]showed that 23% of the Ch and 32% of the PHL in the biliary lipid component are absorbed by the gallbladder in 5 hours. However, only 9% of BA is absorbed. The selective absorptive function of the gallbladder greatly increases the concentration of BA in bile; it can increase by about 10-fold, which prevents crystal formation. The HC technique improved biliary components near the anastomosis using the selective absorption function of the gallbladder.

The bile duct export valve, the SO, is destroyed after HJ. Because the bile duct is completely connected with the intestinal tract, the probability of chyme, bacteria,and air entering the bile duct are greatly enhanced. Once these enter the bile duct, they cannot be expelled rapidly and completely. Intestinal bacteria colonize the bile duct,and stimulate active hyperplasia of the glands, which increases the secretion of mucus. Meanwhile, bacterial multiplication enhances free radical signals, which are dif fi cult to eliminate. Some bacteria secrete exogenous β-glucuronidase, raising UCB levels in bile. Biliary bacterial cultures were positive at 1 and 5 months after HJ. However, cultures were negative at 5 months after HC.These results suggest that the bile duct can be kept aseptic by maintaining the normal function of the SO, which avoids biliary hepatolithiasis formation and augmentation to some degree. Bacterial culture of bile from 2 of 5 dogs was positive at 1 month after HC. We speculate that this might be due to a functional disorder of the SO.

In summary, lipid components, mucin, oxygen free radicals, and bacterial culture results showed that the HC technique was more favorable for preventing the formation of hepatolithiasis. Therefore, in the clinic,STHG should be preferentially considered in patients with hepatolithiasis complicated by intrahepatic biliary stricture and who have approximately normal gallbladders and SOs. However, STHG also changes the anatomic structure of the gallbladder. Therefore, further investigation is needed to evaluate the contractile and emptying functions of the gallbladder, the coordination between relaxation and contraction of the gallbladder and the SO, and the healing of tissues after anastomosis between the gallbladder and bile duct.

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: Not needed.

Contributors: ZXJ and JY proposed the study and wrote the fi rst draft. ZXJ analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study. ZXJ is the guarantor.

Competing interest: No bene fi ts in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Jeng KS. Treatment of intrahepatic biliary stricture associated with hepatolithiasis. Hepatogastroenterology 1997;44:342-351.

2 Murayama A, Hayakawa N, Yamamoto H, Kawabata Y,Kokuryo T, Nagino M, et al. Biliary stricture with hepatolithiasis as a late complication of retrograde transhepatic biliary drainage. Hepatogastroenterology 2003; 50:329-332.

3 Huang MH, Chen CH, Yang JC, Yang CC, Yeh YH, Chou DA, et al. Long-term outcome of percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopic lithotomy for hepatolithiasis. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:2655-2662.

4 Kitagawa Y, Nimura Y, Hayakawa N, Kamiya J, Nagino M,Uesaka K, et al. Intrahepatic segmental bile duct patterns in hepatolithiasis: a comparative cholangiographic study between Taiwan and Japan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2003;10:377-381.

5 Zhao FK. Enlarged choledocho-duodenostomy. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi 1990;28:209-210, 252.

6 Yang YL, Tan WX, Feng ZY, Fu WL, Guo HW, Lang GL, et al.The prevention of hepatolithiasis and biliary stricture post choledochojejunostomy. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi 2006;44:1604-1606.

7 Kuran S, Parlak E, Aydog G, Kacar S, Sasmaz N, Ozden A,et al. Bile re fl ux index after therapeutic biliary procedures.BMC Gastroenterol 2008;8:4.

8 Hwang JH, Yoon YB, Kim YT, Cheon JH, Jeong JB. Risk factors for recurrent cholangitis after initial hepatolithiasis treatment. J Clin Gastroenterol 2004;38:364-367.

9 Mortensen FV, Ishibashi T, Hojo N, Yasuda Y. A gallbladder fl ap for reconstruction of the common bile duct. An experimental study on pigs. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2004;11:112-115.

10 Tian F, Zhao T, Hu J. Hepaticocholangiochole cystostomy plus construction of subcutaneous tunnel of the gallbladder in the treatment of hepatolithiasis with bile duct stricture.Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi 1997;35:28-30.

11 Li X, Shi L, Wang Y, Tian FZ. Middle and long-term clinical outcomes of patients with regional hepatolithiasis after subcutaneous tunnel and hepatocholangioplasty with utilization of the gallbladder. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2005;4:597-599.

12 Krige JE, Bening fi eld SJ. Subcutaneous tunnel and hepatocholangioplasty after resection for intrahepatic stones. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2006;5:474-475.

13 Zhang X, Tian F, Tang L, Chen Q. Animal model building of hepaticojejunostomy and hepaticocholedochostomy and comparison of short-term effect. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi 2005;19:149-152.

14 Moore EW, Vérine HJ. Pathogenesis of pancreatic and biliary CaCO3 lithiasis: the solubility product (K'sp) of calcite determined with the Ca++electrode. J Lab Clin Med 1985;106:611-618.

15 Ahrendt SA, Ahrendt GM, Pitt HA, Moore EW, Lillemoe KD. Hypercalcemia decreases bile fl ow and increases biliary calcium in the prairie dog. Surgery 1995;117:435-442.

16 Osnes T, Sandstad O, Skar V, Osnes M. Lipopolysaccharides and beta-glucuronidase activity in choledochal bile in relation to choledocholithiasis. Digestion 1997;58:437-443.

17 Haigh WG, Lee SP. Identi fi cation of oxysterols in human bile and pigment gallstones. Gastroenterology 2001;121: 118-123.

18 Koppisetti S, Jenigiri B, Terron MP, Tengattini S, Tamura H,Flores LJ, et al. Reactive oxygen species and the hypomotility of the gall bladder as targets for the treatment of gallstones with melatonin: a review. Dig Dis Sci 2008;53:2592-2603.

19 van Erpecum KJ, Portincasa P, Stolk MF, van de Heijning BJ,van der Zaag ES, van den Broek AM, et al. Effects of bile salt and phospholipid hydrophobicity on lithogenicity of human gallbladder bile. Eur J Clin Invest 1994;24:744-750.

20 Ko CW, Lee SP. Gallstone formation. Local factors. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 1999;28:99-115.

21 Ginanni Corradini S, Ripani C, Della Guardia P, Giovannelli L, Elisei W, Cantafora A, et al. The human gallbladder increases cholesterol solubility in bile by differential lipid absorption: a study using a new in vitro model of isolated intra-arterially perfused gallbladder. Hepatology 1998;28:314-322.

BACKGROUND: Optimal surgical technique plays a key role in preventing the postoperative recurrence of hepatolithiasis. Tian et al developed the subcutaneous tunnel and hepatocholangioplasty using the gallbladder (STHG)technique and applied it in hepatolithiasis patients who had an approximately normal gallbladder and sphincter of Oddi.However, the technique is controversial. In the present study,a canine model was established for hepatocholangioplasty(HC) and hepaticojejunostomy (HJ) to simulate STHG and Roux-en-Y cholangiojejunostomy in the clinic, respectively.Then, the alterations of bile components in the vicinity of the anastomosis were compared. This may provide an experimental guide for choosing an optimal technique for the treatment of hepatolithiasis in the clinic.

METHODS: The animals were randomly separated into a control group (5 dogs) and a model group (stenosis of the common bile duct; 24 dogs). The 24 dogs in the model group were randomly divided into an HC group and an HJ group (12/group). Bile was collected from the bile duct at 1 and 5 months after the operation, and the bile components were determined.

RESULTS: The levels of total bile acid, cholesterol, total bilirubin, and phospholipid in the HC group were higher than those in the HJ group (P<0.05). However, no statistical difference was seen in unconjugated bilirubin and calcium ions. The mucin level in bile in the HC group was lower than that in the HJ group at 5 months after the operation (P<0.05).The postoperative lipid peroxidation level was remarkably lower than that in the HJ group (P<0.05). However, the superoxide dismutase level was remarkably higher than that in the HJ group (P<0.05). Finally, a signi fi cant difference was found in the positive bacterial culture rate in bile between the groups.

CONCLUSION: Changes of bile components near the anastomosis after HC might be more preferable for preventing hepatolithiasis formation than HJ.

Author Af fi liations: Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery (Zhang XJ and Jiang Y), and Nursing Department (Wang X), Fuzong Clinical College, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou 350025, China; Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, Center of Hepatobiliary Disease, PLA Fuzhou General Hospital,Nanjing Military Area Command, Fuzhou 350025, China (Jiang Y and Lv LZ); Department of General Surgery, PLA Chengdu General Hospital,Chengdu Military Area Command, Chengdu 610083, China (Tian FZ)

Yi Jiang, MD, Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, Fuzong Clinical College, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou 350025,China (Tel: 86-591-22859377; Fax: 86-591-24937081; Email: zxjin1972@126.com)

© 2010, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

May 22, 2009

Accepted after revision November 7, 2009

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Critical fl icker frequency for diagnosis and assessment of recovery from minimal hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis

- Risk factors for early recurrence of smallhepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection

- Pathological changes at early stage of multiple organ injury in a rat model of severe acute pancreatitis

- Potential etiopathogenesis of seventh day syndrome following living donor liver transplantation: ischemia of the graft?

- Effect of sodium salicylate on oxidative stress and insulin resistance induced by free fatty acids

- Endoscopic nasojejunal feeding tube placement in patients with severe hepatopancreatobiliary diseases:a retrospective study of 184 patients