Outcome of hepatocellular carcinoma treated by liver transplantation: comparison of living donor and deceased donor transplantation

2010-06-29ChuanLiTianFuWenLuNanYanBoLiJiaYingYangWenTaoWangMingQingXuandYongGangWei

Chuan Li, Tian-Fu Wen, Lu-Nan Yan, Bo Li, Jia-Ying Yang, Wen-Tao Wang, Ming-Qing Xu and Yong-Gang Wei

Chengdu, China

Original Article / Transplantation

Outcome of hepatocellular carcinoma treated by liver transplantation: comparison of living donor and deceased donor transplantation

Chuan Li, Tian-Fu Wen, Lu-Nan Yan, Bo Li, Jia-Ying Yang, Wen-Tao Wang, Ming-Qing Xu and Yong-Gang Wei

Chengdu, China

BACKGROUND:Liver transplantation (LT) has been widely accepted as the treatment of choice for end-stage liver diseases. Due to the scarcity of cadaveric donors, adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) is advocated as a practical alternative to deceased donor liver transplantation (DDLT). However, some reports suggest that the long-term and recurrence-free survival rates of LDLT are poorer than those of DDLT for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). This study aimed to compare the long-term and recurrence-free survival rates of HCC between LDLT and DDLT.

METHODS:We retrospectively analyzed the clinical data of 150 patients with HCC from January 2005 to March 2009. Eleven patients who died of complications during the perioperative period were excluded. The remaining 139 eligible patients (101 DDLT and 38 LDLT) were regularly followed up to October 2009. The Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test were used to compare the characteristics of LDLT and DDLT. The long-term and recurrence-free survival curves of both groups were determined using the Kaplan-Meier method with comparisons performed using the log-rank test. One-way analysis of variance was performed to compare the waiting time of the two groups.

RESULTS:Survival rates at 1, 2, 3, and 4 years for LDLT were 81%, 62%, 53%, and 45% and for DDLT were 86%, 60%, 50%, and 38%, respectively. The overall 1-, 2-, 3-, and 4-year recurrence-free rates for LDLT were 71%, 49%, 42%,and 38%, and for DDLT were 76%, 52%, 41%, and 37%, respectively. No significant differences were found by the logrank test on both long-term and recurrence-free survival rates.

CONCLUSIONS:The role of LDLT is reinforced by our study. It may expand the donor pool and achieve the same long-term and recurrence-free survival rates of DDLT.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2010; 9: 366-369)

hepatocellular carcinoma; liver transplantation; living donor; deceased donor; long-term survival; recurrence-free survival

Introduction

Liver transplantation (LT) is advocated as a good management for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). It may cure the tumor, underlying cirrhosis, and severe liver dysfunction. For strictly selective criteria, such as the Milan and UCSF criteria, the 5-year survival rate of patients who undergo transplantation for HCC is comparable to recipients who undergo transplantation for benign liver diseases.[1,2]Nonetheless, LT is greatly limited by the shortage of liver grafts. The long waiting period leads to tumor progression and dropout of patients from the waiting list.[3,4]Living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) is perceived as an alternative to deceased donor liver transplantation (DDLT) due to the limited availability of cardiac death donors. It may expand the donor pool, shorten the waiting time and prevent dropout of patients from the waiting list due to tumor progression.[5-7]However, some investigators have suggested that the long-term and recurrence-free survival rates of LDLT are not satisfactory.[8,9]The aim of this study was to compare the long-term and recurrence-free survival rates between LDLT and DDLT.

Methods

Patients and study groups

Between January 2005 and March 2009, 150 patients with HCC underwent LT at our center. Diagnosis was confirmed by histological examination of the explanted liver. We excluded patients who died of complications during the perioperative period (n=11) and retrospectively analyzed the clinical data of the remaining 139 at the time of transplantation. According to the differences in liver grafts, the 139 patients were divided into a DDLT group (n=101) and an LDLT group (n=38). Patients with preoperative extrahepatic tumors were excluded from the waiting list. All clinical data which may affect tumor recurrence were considered in this study, including preoperative alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level, tumor size, tumor differentiation, total tumor nodules, tumor vascular invasion, criteria beyond the Milan criteria, TNM classification, pretransplant treatments, recipient age and gender. Pathological examination was performed on all removed livers.

Donor selection

All living donors were required to be healthy relatives with normal liver function, without any acute and/or chronic disease and with a compatible ABO blood type, and negative serology for HBsAg, hepatitis C antibody, and HIV antibody. The donor liver was evaluated by CT angiography or MR imaging and a right lobe graft without the middle hepatic vein of the eligible donor was selected to provide a graft at least 0.8% of the recipient's body weight as estimated and at least 40% remnant liver for the donor.[10]

Follow-up

After transplantation, recipients were monitored by serum AFP examination, visceral ultrasonography or CT or MR imaging and chest radiography every 3 months. Bone scintigraphy was performed whenever HCC recurrence was suspected. Recurrence was defined as positive imaging findings compared to preoperative examination values and newly rising tumor marker (AFP) values or confirmed by biopsy or resection. All cases were regularly followed up to recurrence, death, or the termination of this study (October 2009).

Immunosuppression and antiviral protocols

Immunosuppressive maintenance was given with tacrolimus or cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil and steroid after LT. Steroid pulse therapy was conducted in patients with rejection. Whenever possible, the steroid was tailed off within 6 months to minimize the risk of recurrence. Antivirus therapy of HBsAgpositive patients was lamivudine before and after transplantation.[11]Moreover, hepatitis B immune globulin was administered to HBV patients before, during, and after transplantation.[12]

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS13.0 for Windows. The Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used to compare LDLT and DDLT for general characteristics. Recurrence-free and long-term survival rates were determined using the Kaplan-Meier method with comparisons using the log-rank test.Pvalues of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

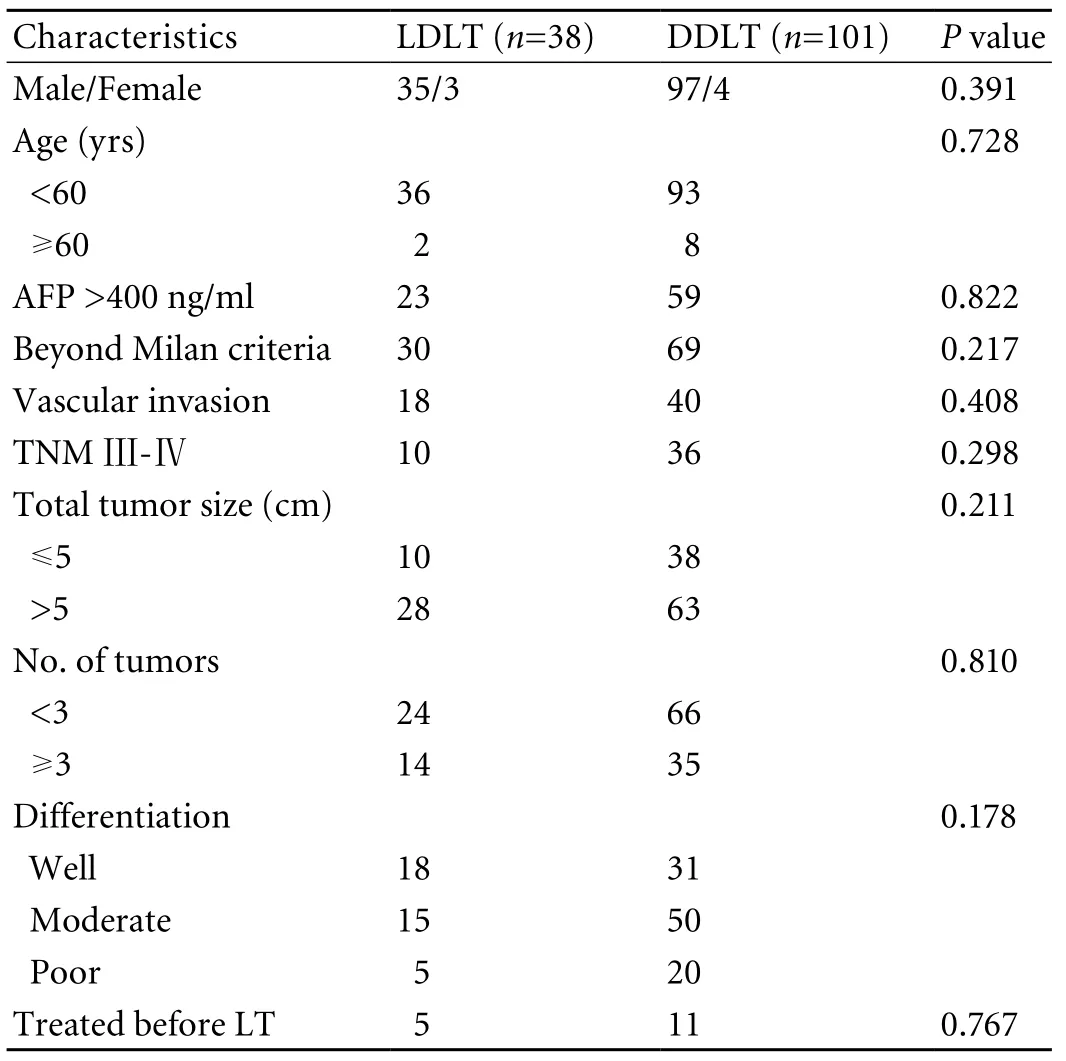

General characteristics of explanted liver and recipients

All tumor and pathological data were determined on the explanted liver after transplantation. The general characteristics of the LDLT and DDLT groups are shown in Table 1. In general, there were no significant differences in recipient age, gender, AFP level, beyond the Milan criteria, vascular invasion, total tumor size, tumor nodules and tumor differentiation (Table 1). HBV and liver cirrhosis were detected in all patients.

Table 1. Characteristics of LDLT and DDLT recipients

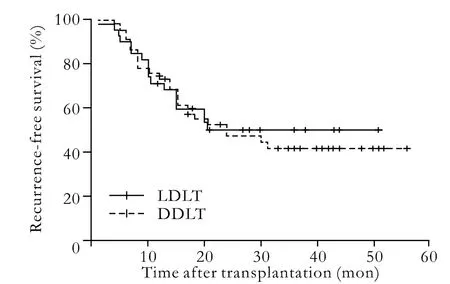

Fig. 1. Comparison of the recurrence-free rates of LDLT and DDLT (P=0.787).

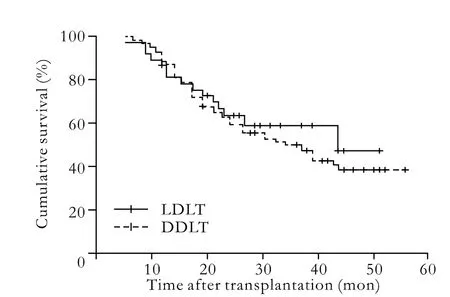

Fig. 2. Comparison of the overall survival rates of LDLT and DDLT (P=0.571).

Recurrence and survival rates after transplantation

The median waiting times for LDLT and DDLT were 3.71 and 6.92 weeks, respectively, and one-way analysis of variance revealed a significant difference (P=0.045). The median time of follow-up was 25.15±14.36 months. Recurrence was observed in 71 patients (51.08%), 66 died of tumor recurrence, and 5 survived with tumor. Moreover, 1 patient without recurrence committed suicide. The overall 1-, 2-, 3-, and 4-year recurrencefree rates were 71%, 49%, 42%, and 38% for LDLT recipients versus 76%, 52%, 41%, and 37% for DDLT recipients (P=0.787). The overall patient survivals at 1, 2, 3, and 4 years were 81%, 62%, 53%, and 45% after LDLT respectively, and 86%, 60%, 50%, and 38% after DDLT (P=0.571). No significant difference in recurrence-free and long-term survival rates between LDLT and DDLT was revealed by the log-rank test (Figs. 1, 2).

Discussion

In the past, the outcome of patients with HCC who underwent LT at our center was not satisfactory. The lack of universal criteria in the early transplantation days in the mainland of China may explain these disappointing results. For this reason, some patients with advanced tumor underwent LT in those days. However, investigators in China realized this situation and proposed standards, such as the Hangzhou criteria,[13]so we believe the outcome will continue to improve.

LT is a good choice for end-stage liver disease but is greatly limited by the shortage of cadaveric donors. Since 1989, when the first successful LDLT for a child was performed in Australia, the donor pool has expanded.[14]Now, LDLT is considered as an alternative to the limited availability of cardiac death donors and theoretically provides an unlimited resource of liver grafts. In our center, LDLT is increasing. However, the outcome of LDLT for HCC is controversial. Some investigators suggested that, for HCC, it may contribute to poor recurrence-free and long-term survival.[8]

Some investigators suggested that the short waiting time and the operative procedure for LDLT may contribute to a poor outcome. The waiting time for DDLT is much longer than that for LDLT. Some authors reported that the increased waiting time leads to at least 20%-30% of candidates dropping out before receiving grafts due to tumor progression.[3,15]LDLT is called "fast-track" transplantation because of the short waiting time.[15]So, due to a short waiting time which does not permit adequate time to access the biological behavior of the tumor, more patients with aggressive tumors may be included in the LDLT group.[15,16]Moreover, some authors suggested that hepatectomy in LDLT is not radical.[16,17]LDLT needs to preserve the native vena cava as well as the greater length of the hepatic artery and bile duct. All of these may result in tumor remnants which become the root of recurrence. Another potential explanation is that more manipulation during LDLT may lead to dissemination of HCC via the hepatic vein. All of these surgical procedures and the short waiting time for LDLT may promote the recurrence of HCC.[17]Despite these arguments that LDLT is poorer than DDLT for HCC, our experience demonstrated no significant differences in both long-term and recurrence-free survival rates among patients who underwent LDLT versus DDLT with many recipients beyond the Milan criteria. Di Sandro et al[16]reported that LDLT guarantees the same longterm results as DDLT. Furthermore, in a large cohort study by Dumortier et al,[18]LDLT was able to improve the access to LT and achieved a 1-year survival similar to DDLT. As in many previous studies,[12,19-21]we suggested that tumor characteristics, such as total tumor size and vascular invasion adversely affect the outcome after transplantation, rather than DDLT or LDLT.[12]

Other favorable conclusions for LDLT have been reported. Cheng et al[22,23]hypothesized that patientswith HCC who are disadvantaged by the allocation algorithm for liver grafts from deceased donors may benefit a lot from LDLT for the fast-track transplantation using an analytic model. Lai et al[24]reported although LDLT includes additional cost to the donor and may increase the operative complexity, the overall financial burden is similar to DDLT. We suggest that LDLT also has such advantages as nearly no warm ischemia injury and significantly shorter cold ischemia time. These advantages ensure grafts and recipients in excellent conditions. Thus the prognosis of LDLT will be improved.

In conclusion, the role of LDLT for HCC is strengthened by our finding of similar recurrence-free and long-term survival rates in the DDLT and LDLT groups. LDLT will not only expand the donor pool for benign end-stage liver diseases but also for malignancies.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Contributors:LC and WTF proposed the study and wrote the first draft. LC analyzed tha data. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts. WTF is the guarantor.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 1996;334:693-699.

2 Yao FY, Ferrell L, Bass NM, Watson JJ, Bacchetti P, Venook A, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: expansion of the tumor size limits does not adversely impact survival. Hepatology 2001;33:1394-1403.

3 Llovet JM, Bruix J. Novel advancements in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma in 2008. J Hepatol 2008;48:S20-37.

4 Mazzaferro V, Chun YS, Poon RT, Schwartz ME, Yao FY, Marsh JW, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2008;15:1001-1007.

5 Trotter JF. Selection of donors and recipients for living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2000;6:S52-58.

6 Bak T, Wachs M, Trotter J, Everson G, Trouillot T, Kugelmas M, et al. Adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation using right-lobe grafts: results and lessons learned from a single-center experience. Liver Transpl 2001;7:680-686.

7 Chan SC, Fan ST, Lo CM, Liu CL, Wei WI, Chik BH, et al. A decade of right liver adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation: the recipient mid-term outcomes. Ann Surg 2008;248:411-419.

8 Malagó M, Sotiropoulos GC, Nadalin S, Valentin-Gamazo C, Paul A, Lang H, et al. Living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a single-center preliminary report. Liver Transpl 2006;12:934-940.

9 Lo CM, Fan ST, Liu CL, Chan SC, Ng IO, Wong J. Living donor versus deceased donor liver transplantation for early irresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg 2007;94:78-86.

10 Ran S, Wen TF, Yan LN, Li B, Zeng Y, Chen ZY, et al. Risks faced by donors of right lobe for living donor liver transplantation. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2009;8:581-585.

11 Zhang J, Zhou L, Zheng SS. Clinical management of hepatitis B virus infection correlated with liver transplantation. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2010;9:15-21.

12 Li J, Yan LN, Yang J, Chen ZY, Li B, Zeng Y, et al. Indicators of prognosis after liver transplantation in Chinese hepatocellular carcinoma patients. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15:4170-4176.

13 Zheng SS, Xu X, Wu J, Chen J, Wang WL, Zhang M, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: Hangzhou experiences. Transplantation 2008;85:1726-1732.

14 Strong RW, Lynch SV, Ong TH, Matsunami H, Koido Y, Balderson GA. Successful liver transplantation from a living donor to her son. N Engl J Med 1990;322:1505-1507.

15 Yao FY, Bass NM, Nikolai B, Davern TJ, Kerlan R, Wu V, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of survival according to the intention-to-treat principle and dropout from the waiting list. Liver Transpl 2002;8:873-883.

16 Di Sandro S, Slim AO, Giacomoni A, Lauterio A, Mangoni I, Aseni P, et al. Living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: long-term results compared with deceased donor liver transplantation. Transplant Proc 2009;41:1283-1285.

17 Fisher RA, Kulik LM, Freise CE, Lok AS, Shearon TH, Brown RS Jr, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence and death following living and deceased donor liver transplantation. Am J Transplant 2007;7:1601-1608.

18 Dumortier J, Adham M, Ber C, Boucaud C, Bouffard Y, Delafosse B, et al. Impact of adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation on access to transplantation and patients' survival: an 8-year single-center experience. Liver Transpl 2006;12:1770-1775.

19 Mazzaferro V, Llovet JM, Miceli R, Bhoori S, Schiavo M, Mariani L, et al. Predicting survival after liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the Milan criteria: a retrospective, exploratory analysis. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:35-43.

20 Hemming AW, Cattral MS, Reed AI, Van Der Werf WJ, Greig PD, Howard RJ. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg 2001;233:652-659.

21 Shetty K, Timmins K, Brensinger C, Furth EE, Rattan S, Sun W, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma validation of present selection criteria in predicting outcome. Liver Transpl 2004;10:911-918.

22 Cheng SJ, Pratt DS, Freeman RB Jr, Kaplan MM, Wong JB. Living-donor versus cadaveric liver transplantation for non-resectable small hepatocellular carcinoma and compensated cirrhosis: a decision analysis. Transplantation 2001;72:861-868.

23 Fan ST. Live donor liver transplantation in adults. Transplantation 2006;82:723-732.

24 Lai JC, Pichardo EM, Emond JC, Brown RS Jr. Resource utilization of living donor versus deceased donor liver transplantation is similar at an experienced transplant center. Am J Transplant 2009;9:586-591.

March 8, 2010

Accepted after revision June 16, 2010

Author Affiliations: Liver Transplantation Center, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, China (Li C, Wen TF, Yan LN, Li B, Yang JY, Wang WT, Xu MQ and Wei YG)

Tian-Fu Wen, MD, Liver Transplantation Center, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, China (Tel: 86-18980601471; Email: ccwentianfu@sohu.com)

© 2010, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International (HBPD INT)

- Efficacy of Shanvac-B recombinant DNA hepatitis B vaccine in heaIth care workers of Northern India

- Inflammatory boweI diseases and hepatitis C virus infection

- Radiofrequency ablation, heat shock protein 70 and potential anti-tumor immunity in hepatic and pancreatic cancers: a minireview

- Norcantharidin inhibits growth of human gallbladder carcinoma xenografted tumors in nude mice by inducing apoptosis and blocking the cell cycle in vivo

- Meetings and Courses