Efficacy of Shanvac-B recombinant DNA hepatitis B vaccine in heaIth care workers of Northern India

2010-06-29VarshaThakurNirupmaPatiRajkumarGuptaandShivSarin

Varsha Thakur, Nirupma T Pati, Rajkumar C Gupta and Shiv K Sarin

New Delhi, India

Efficacy of Shanvac-B recombinant DNA hepatitis B vaccine in heaIth care workers of Northern India

Varsha Thakur, Nirupma T Pati, Rajkumar C Gupta and Shiv K Sarin

New Delhi, India

BACKGROUND:Health care workers (HCWs) constitute a high-risk population of HBV infection. There are limited data on the efficacy of vaccination in HCWs in India. This study was to evaluate the efficacy of indigenous recombinant hepatitis B vaccine, Shanvac-B, in HCWs.

METHODS:In 597 HCWs screened before the vaccination, 216 (36.2%) showed the presence of at least one of the markers of HBV/HCV infection. Of the remaining 381 (63.8%) HCWs who were considered for vaccination, only 153 (age 18-45 years; 48 males and 105 females) were available for final assessment. These HCWs received 20 μg of vaccine at 0, 1 and 6 months. They were asked for the reactogenicity and monitored for the seroprotective efficacy of the vaccination. Anti-HBs titres were measured after vaccination at 1, 2 and 7 months. The presence of anti-HBs titers equal to 1 MIU/ml was considered as seroconversion and that of titres greater than 10 MIU/ml as seroprotection.

RESULTS:After vaccination, 32 males (67%) and 76 females (72%) showed seroconvertion; finally 12 (25%) of the males and 47 (45%) of the females were seroprotected. Seroprotection at 2 and 7 months was more dominant in the females than in the males (96% vs. 56%,P=0.001, 100% vs. 85%,P=0.0001), respectively. Geometric mean titres of anti-HBs after vaccination were also higher in the females than in the males (257±19.7 vs. 29±1.88 MIU/ml,P=0.01, 1802±35.2 vs. 306±13.6 MIU/ml,P≤0.05, 6465±72 vs. 2142±73.6 MIU/ml,P<0.05). Seven male HCWs showed unsatisfactory response, non-response (n=3, 6%) and hypo-response (≤10 MIU/ml,n=4, 8%) at the end of vaccination. Smoking and alcoholism were significantly correlated with unsatisfactory response. No significant adverse effects of vaccination were observed in any HCW.CONCLUSIONS:The presence of HBsAg in HCWs indicates that a high proportion of HCWs are infected with HBV and HCV in India. Recombinant indigenous vaccine Shanvac-B is highly efficacious in HCWs, and its immunogenicity is significantly higher in females than in males. However, prevaccination screening of HCWs is strongly recommended in India.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2010; 9: 393-397)

health care workers; hepatitis B virus; hepatitis C virus; seroprotection; immunogenicity; Shanvac-B

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a global health problem. The frequency of hepatitis B viral infection in a subset of population is a function of several factors, which increases the risk of viral entry. These include environmental and life style related factors contributing to the acquisition of HBV infection. Health care workers (HCWs) constitute a high risk group for acquiring infection with blood born pathogens due to occupational contact with infected body fluid.[1]HBV is one of the five major hepatotropic viruses responsible for 60% of patients with chronic liver disease in India.[2]The prevalence of HBV infection in HCWs depends upon its prevalence in the general population. In India, the estimated prevalence rate of HBV in the healthy general population is around 4.7%, which places India in an intermediate endemic zone.[3]A recent study revealed that the positivity of HBsAg is around 5% in HCWs in India, with the highest seropositivity of around 40% among laboratory technicians.[4]The incidence of HBV-related acute viral hepatitis was the highest among HCWs with a seropositivity of 45.5%, followed by 33.3% in therecipients of multiple blood transfusions.[5]A recent study from Taiwan found that in the HCWs who were exposed to high-risk patients, nearly 16% had HBV and 12.7% had HCV infection.[6]The risk of HBV and HCV infection ranged from 308- to 924-fold in the HCWs compared to the general population. In another study from Turkey, 18.7% of HCWs especially nurses were found to be HBV infected. More importantly, 28% of them were not vaccinated against HBV.[7]Studies from Western countries also showed a high prevalence of HBV infection (all markers) in HCWs, ranging from 17%-30%.[8,9]whereas a prevalence <0.1% for HBV infection in the general population. HBV infection can be prevented by vaccination, and it has been strongly recommended for HCWs.[10]There are adequate data on HBV vaccination in HCWs suggesting good response albeit lower than those observed in the general population.[11-14]The decreased immunogenicity of HBV vaccine in HCWs has been attributed to increasing age, male gender, obesity, smoking and chronic diseases among older adults.[13]

High cost of available vaccines is a major limiting factor for universal vaccination of the high-risk group like HCWs in a developing country like India. Recently, a new recombinant vaccine, Shanvac-B, has been shown to be safe, efficacious and cost-effective in the healthy Northern Indian population.[15]Seroconversion was found in 43 (53%) of subjects one month after first vaccination. Among them, 26% were seroprotected, 99% and 100% of the subjected had seroprotection after second and third vaccination respectively. However, there is paucity of data regarding immunogenicity of Shanvac-B in HCWs. The present study was undertaken to evaluate the efficacy and immunogenicity of the indigenous hepatitis B vaccine, Shanvac-B, in HCWs of Northern India.

Methods

A total of 597 HCWs from two hospitals in New Delhi, India, included doctors (n=100), nurses (n=250), nursing attendants (n=146), laboratory technicians and other supporting staff (n=101), from whom informed written consent was obtained. There were 247 males and 350 females with a mean age of 35±7 years. A detailed questionnaire was designed to assess the precise nature of their job, the duration of exposure to blood and blood products, if any, high-risk behavior, awareness and practice of universal precautions. The screening included test for markers of HBV (HBsAg, IgG anti-HBc, anti-HBe, anti-HBs) and HCV (anti-HCV) infection using commercially available enzyme immunoassay kits (Abbott Labs, North Chicago, IL., USA).

Vaccination protocol

The subjects who fulfilled the following selection criteria were enrolled into the vaccination protocol: Age between 18-45 years; seronegativity for HBsAg, anti-HBs, IgG anti-HBc, anti-HBe and anti-HCV.

Exclusion criteria included history of prior exposure to HBV or HCV, incomplete or complete course of vaccination, blood transfusion or presence of any serious systemic disease such as chronic renal failure, congestive heart failure, bleeding diathesis, pregnancy, lactation, overt malignancy, lack of consent.

20 μg of vaccine (recombinant HBsAg) was administered intramuscularly in the deltoid region at 0, 1, and 6 months. The first vaccination was given within seven days after the availability of the screening results. The subjects were asked to report any adverse effects and monitored on the first 3 days. One month after each vaccination, the serum anti-HBs titer was quantitated, at months 1, 2 and 7, with an automated immunoassay analyzer (IMX from Abbott Lab, North Chicago, IL., USA), based on microparticle enzyme immunoassay (MEIA). The analyte (anti-HBs) was captured on coated micro particles. The immune complex was detected with alkaline phosphatase labeled conjugate and fluorogenic substrate. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the hospital and the use of the vaccine was approved by the Drug Controller General of India.

The results of vaccination were defined: Seroconversion: presence of detectable anti-HBs >1 MIU/ml antibody; seroprotection: presence of >10 MIU/ml of anti-HBs titres; unsatisfactory response: absence or presence of <1 MIU/ml anti-HBs titres (non-response) or anti-HBs titres <10 MIU/ml (hypo-response) one month after completion of the full vaccination schedule; and reactogenicity: nature and incidence of reaction/ adverse event after each vaccination. Local and general symptoms including fever, pain, edema, rash, redness, fatigue, headache, body ache, allergy, nausea and vomiting after each vaccination.

Statistical analysis

The post-vaccination geometric mean titer was presented as mean±SE. The significance of differences between discontinuous variables was tested by the Chi-square test and Fisher's exact test. For continuous variables, wilcoxon's rank-sum text, the Mann-WhitneyUtest and Friedman's test were used. APvalue of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Prevalence of hepatitis markers in HCWs

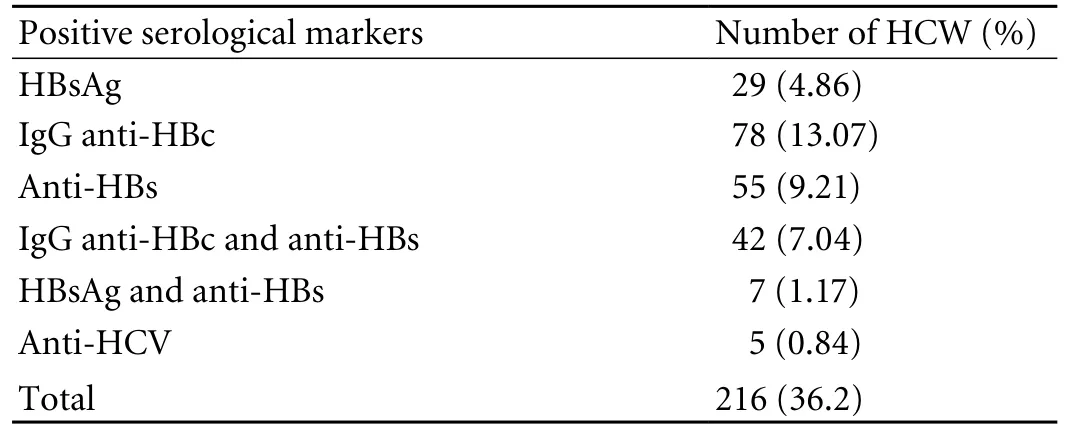

In 216 (36.2%) of the 597 HCWs, at least one marker of either HBV or HCV infection was found. HBsAg was positive in 29 subjects (4.86%) and anti-HBs (>10 MIU/ml) titer was present in 7 subjects (1.17%). Other markers of HBV infection such as IgG anti-HBc and anti-HBs and anti-HBe were detected in 175 subjects (29.3%) who had only anti-HBs (>10 IU/L) without other markers of HBV infection or denied a history of vaccination against HBV (Table 1). Possibly they forgot or were not willing to accept that they had received vaccination in the past. We had to exclude these HCWs.

The prevalence of anti-HCV antibody was detected in only 5 subjects (0.84%). Thus, after the initial screening, 216 subjects (36.2%) with one or more marker of HBV or HCV infection were excluded. The remaining 381 subjects (63.8%) were eligible for vaccination.

Vaccination

Of the 381 HCWs, 167 (43.8%) either showed inability to come for regular vaccination due to the nature of their job or did not give consent for the vaccination. 214 HCWs were started on the vaccination protocol. However, 13 HCWs (3.4%) took only one vaccination, 7 (1.8%) took two vaccinations, and 41 (10.8%) did not come after receiving all the 3 vaccinations for testing anti-HBs levels. Thus, 153 HCWs (48 male and 105 female HCWs) who completed the vaccination schedule and took all vaccinations were analyzed finally.

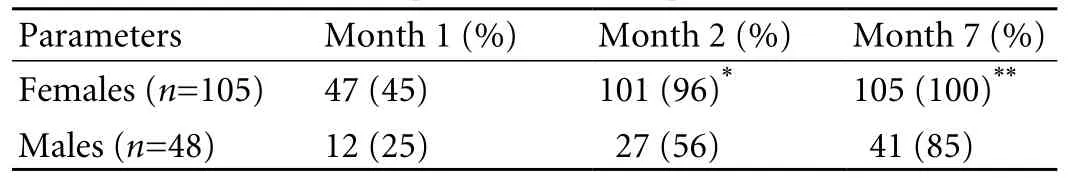

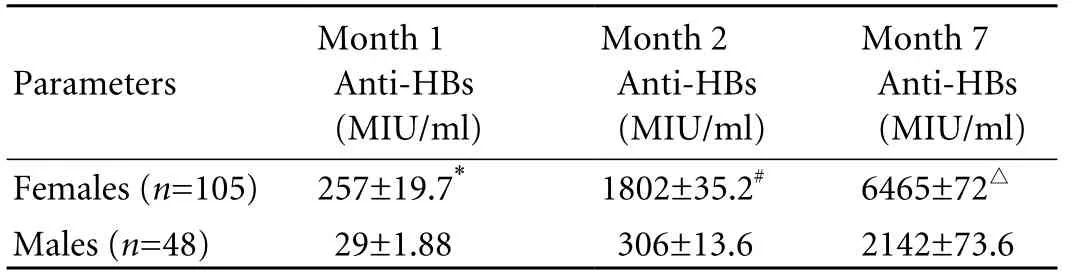

After the first vaccination, 76 females (72%) and 32 males (67%) were seroconverted, and 47 females (45%)and 12 males (25%) were seroprotected with mean geometric titers of anti-HBs 257±19.7 and 29±1.88 MIU/ ml respectively. The percentage of seroprotected subjects after the second and third vaccinations at months 2 and 7 was significantly higher in females than in males respectively (96% vs. 56%,P=0.001 and 100% vs. 85%,P=0.0001) (Table 2). The mean geometric titers of anti-HBs after each vaccination at months 1, 2 and 7 were significantly higher in females than males (257±19.7 vs. 29±1.88 MIU/ml,P=0.01, 1802±35.2 vs. 306±13.6 MIU/ml,P≤0.05, and 6465±72 vs. 2142±73.6 MIU/ml,P<0.05) (Table 3).

Table 1. Prevalence of HBV and HCV infection in HCWs (n=597)

Table 2. Profile and spectrum of seroprotection in HCWs

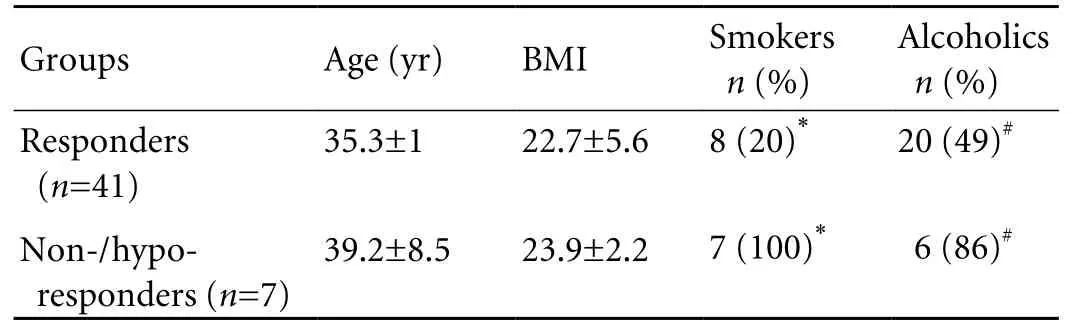

At the end of vaccination, 7 (14.6%) of 48 subjects, all male, showed unsatisfactory response. No response was noted in 3 (6%) and hypo-response (anti-HBs titre less than 10 MIU/ml) in 4 subjects (8%).

The correlation of obesity, smoking and alcoholism with response and non-/hypo-response to Shanvac-B in male subjects are shown in Table 4. Seven subjects who had poor response (anti-HBs <10 MIU/ml) or did not respond (anti-HBs negative) were older (39.2±8.5 years vs. 35.3±1 years,P=ns) with a high body mass index (23.9± 2.2 vs. 22.7±5.6,P=ns) than responders; however, the difference was not significant. The percentage of smokers and alcoholics was significantly higher in subjects who had non-hypo-response to Shanvac-B than in responders (100% vs. 20%,P<0.05, and, 86% vs. 49%,P<0.05).

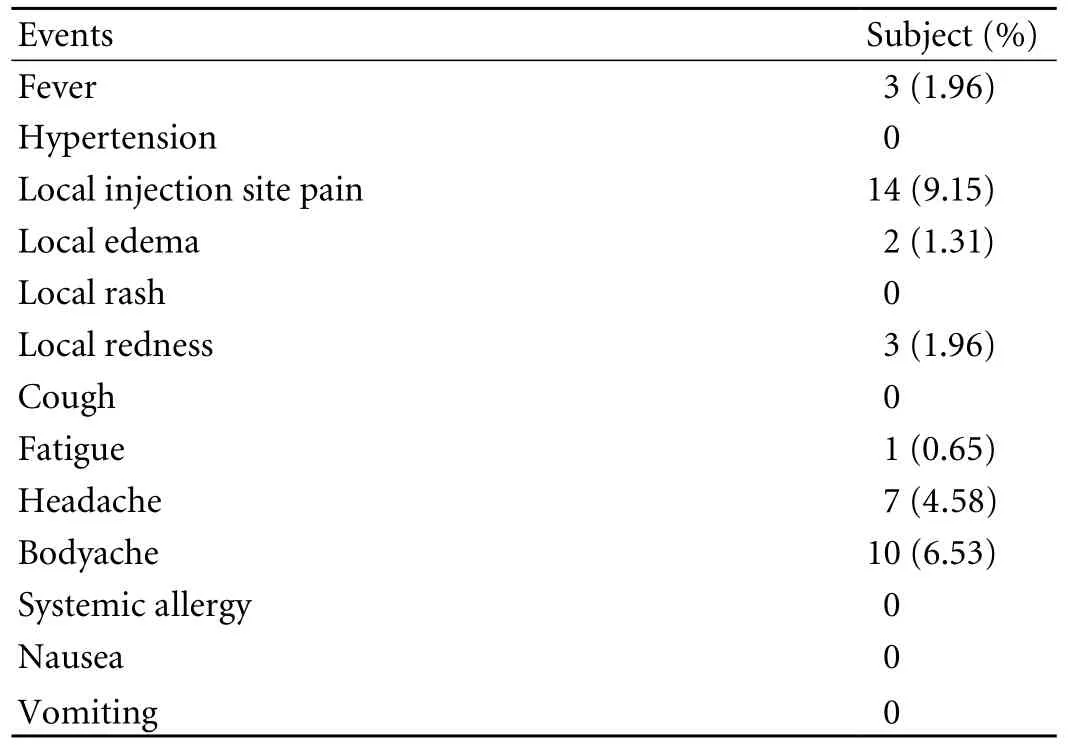

No severe adverse events were reported postvaccination. Mild pain at the site of vaccination and body ache were the commonest symptoms (Table 5).These symptoms recovered spontaneously within the next 2-3 days.

Table 3. Post-vaccination geometric mean titres of anti-HBs

Table 4. Comparison of probable factors responsible for non-/ hypo- response to vaccination in male subjects

Table 5. Post-vaccination adverse events/symptoms (n=153)

Discussion

In the 597 HCWs screened, 216 (36.2%) had at least one of the markers of HBV or HCV infection, showing that a high percentage of HCWs contract HBV or HCV infection in India. HBsAg was positive in 4.9% of HCWs, similar to that observed in a recent study in India.[4]The proportion (29%) of HCWs who had exposure to HBV was nearly two-fold higher than that (IgG anti-HBc positivity 11%) of the general population. The prevalence of HBV infection in HCWs was proportional to the prevalence of HBV in the general healthy population. Our data showed the high prevalence of HBV in HCWs in India and the need of vaccination. Even in the developed countries, around 1%-10% of HCWs are positive for hepatitis B virus infection.[16]Earlier studies have shown that the incidence of HBV infection declined by 95% in HCWs with HBV vaccination.[15,16]Thus, HBV vaccination in this high-risk population is necessary to reduce the HBV pool. Recently, we have reported the therapeutic benefits of vaccination in family members who were exposed to HBV-related chronic liver disease.[17]The expensive vaccination against HBV is a major limiting factor in developing countries like India.

The newly developed indigenous recombinant vaccine costs less, but is safe and efficacious in the healthy adult Indian population.[15]The response to this vaccine was better in female HCWs than in male ones. The percentage of subjects who were seroprotected (anti-HBs titres >10 MIU/ml) at the first month was slightly higher in females than in males (44% vs. 21%), though the difference was not significant. However, the proportion of seroprotected female HCWs was significantly higher after the 2nd and 3rd vaccinations at month 2 and 7 than that the male HCWs (95% vs. 57% and 100% vs. 85%) (Table 2). Early studies showed that the decreased immunogenicity of HBV vaccination was associated with increasing age, obesity, smoking, and male gender.[13]In the present study, the lower response to the vaccine in males was related to gender and smoking behavior. However, the relation of gender to vaccine response was not consistent and also, not considered when vaccination programme was developed.[18,19]Moreover, the 7 subjects with non-/ hypo-response to the vaccine were smokers. Hence, smoking could be one of the reasons for lower response in males compared to females because smoking is not common in Indian females.

Protection against HBV may be effective after 1 or 2 vaccinations for hepatitis B, but optimal and longterm protection is not achieved until vaccination.[20,21]The mean anti-HBs titers after each vaccination were 257, 1802 and 6465 MIU/ml respectively in females, but 29, 306 and 2142 MIU/ml in males (P<0.01, <0.05, <0.05). The efficacy of indigenous vaccine, Shanvac-B, in HCWs is comparable to that observed in another study.[15]Shanvac-B in the present study showed the rate of seroprotection after the first vaccination (39%) was higher that that of the study by Abraham et al (26%). After the second and third vaccinations at month 2 and 7, the rate of seroprotection in HCWs was lower than that reported elsewhere (83% vs. 99%,P<0.05, 95% vs. 100%).[15]The higher seroprotection rate in healthy Indian adults could be related to a greater number of female subjects in their study[15](75 of the 81 subjects were female). The results of the present study confirmed the mean geometric titer of anti-HBs was lower in HCWs than in healthy adults.[22]

In summary, the indigenous recombinant HBV vaccine, Shanvac-B, is safe and efficacious in prevention of HBV confection in HCWs. Being economical, it would be a useful tool to reduce the incidence of HBV infection in developing countries. Our data clearly support pre-vaccination screening for all HCWs in India and post-vaccination screening in male HCWs, specially, if they are regular smokers and abuse alcohol.

Funding:This study was supported by a grant from Shanta Biotec, Hyderabad, India.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Contributors:SSK proposed the study. TV and GRC partially conducted the study. PNT wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts. SSK is the guarantor.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Fay OH. Hepatitis B in Latin America: epidemiological patterns and eradication strategy. The Latin American Regional Study Group. Vaccine 1990;8:S100-106; discussion S134-139.

2 Sarin SK, Guptan RC, Banerjee K, Khandekar P. Low prevalence of hepatitis C viral infection in patients with nonalcoholic chronic liver disease in India. J Assoc Physicians India 1996;44:243-245.

3 Thyagarajan SP, Jayaram S, Mohanavalli B. Prevalence of HBV in the general population of India. In: Sarin SK, Singhal AK, editors. Hepatitis B in India: Problems and Prevention, New Delhi, CBS Publishers;1996:5-16.

4 Ganju SA, Goel A. Prevalence of HBV and HCV infection among health care workers (HCWs). J Commun Dis 2000; 32:228-230.

5 Hazra BR, Saha SK, Mazumder AK, Deb A, Sinha S. Incidence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection amongst clinically diagnosed acute viral hepatitis cases and relative risk of development of HBV infection in high risk groups in Calcutta. Indian J Public Health 1998;42:56-58.

6 Shiao J, Guo L, McLaws ML. Estimation of the risk of bloodborne pathogens to health care workers after a needlestick injury in Taiwan. Am J Infect Control 2002;30: 15-20.

7 Kosgeroglu N, Ayranci U, Vardareli E, Dincer S. Occupational exposure to hepatitis infection among Turkish nurses: frequency of needle exposure, sharps injuries and vaccination. Epidemiol Infect 2004;132:27-33.

8 Panlilio AL, Shapiro CN, Schable CA, Mendelson MH, Montecalvo MA, Kunches LM, et al. Serosurvey of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus infection among hospital-based surgeons. Serosurvey Study Group. J Am Coll Surg 1995;180:16-24.

9 Petrosillo N, Puro V, Ippolito G, Di Nardo V, Albertoni F, Chiaretti B, et al. Hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus infection in health care workers: a multiple regression analysis of risk factors. J Hosp Infect 1995;30:273-281.

10 Hakre S, Reyes L, Bryan JP, Cruess D. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus among health care workers in Belize, Central America. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1995;53:118-122.

11 Mulley AG, Silverstein MD, Dienstag JL. Indications for use of hepatitis B vaccine, based on cost-effectiveness analysis. N Engl J Med 1982;307:644-652.

12 No authors listed. Recommendations for preventing transmission of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B virus to patients during exposure-prone invasive procedures. AORN J 1991;54:576-582.

13 Ferraz ML, de Oliveira PM, Figueiredo VM, Kemp VL, Castelo Filho A, Silva AE. The optimization of the use of economic resources for vaccination against hepatitis B in professionals in the health area. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 1995;28:393-403.

14 Palmovic D, Crnjakovic-Palmovic J. Vaccination against hepatitis B: results of the analysis of 2000 population members in Croatia. Eur J Epidemiol 1994;10:541-547.

15 Abraham P, Mistry FP, Bapat MR, Sharma G, Reddy GR, Prasad KS, et al. Evaluation of a new recombinant DNA hepatitis B vaccine (Shanvac-B). Vaccine 1999;17:1125-1129.

16 Karpuch J, Scapa E, Eshchar J, Waron M, Bar-Shany S, Shwartz T. Vaccination against hepatitis B in a general hospital in Israel: antibody level before vaccination and immunogenicity of vaccine. Isr J Med Sci 1993;29:449-452.

17 Thakur V, Guptan RC, Basir SF, Parvez MK, Sarin SK. Enhanced immunogenicity of recombinant hepatitis B vaccine in exposed family contacts of chronic liver disease patients. Scand J Infect Dis 2001;33:618-621.

18 Mahoney FJ, Stewart K, Hu H, Colemn P, Alter MJ. Progress toward the elimination of hepatitis B virus transmission among health care workers in the United States. Arch Intern Med 1997;157:2601-2605.

19 Alter MJ, Hadler SC, Margolis HS, Alexander WJ, Hu PY, Judson FN, et al. The changing epidemiology of hepatitis B in the United States. Need for alternative vaccination strategies. JAMA 1990;263:1218-1222.

20 Averhoff F, Mahoney F, Coleman P, Schatz G, Hurwitz E, Margolis H. Immunogenicity of hepatitis B Vaccines. Implications for persons at occupational risk of hepatitis B virus infection. Am J Prev Med 1998;15:1-8.

21 Oliveira PM, Silva AE, Kemp VL, Juliano Y, Ferraz ML. Comparison of three different schedules of vaccination against hepatitis B in health care workers. Vaccine 1995;13: 791-794.

22 Dienstag JL, Werner BG, Polk BF, Snydman DR, Craven DE, Platt R, et al. Hepatitis B vaccine in health care personnel: safety, immunogenicity, and indicators of efficacy. Ann Intern Med 1984;101:34-40.

November 1, 2009

Accepted after revision May 11, 2010

Author Affiliations: Department of Gastroenterology, GB Pant Hospital, New Delhi, India (Thakur V, Pati NT, Guptan RC and Sarin SK)

Shiv K Sarin, MD, Department of Gastroenterology, GB Pant Hospital, New Delhi, India (Fax: 91-11-23219710; Email: sksarin@ nda.vsnl.net.in)

© 2010, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International (HBPD INT)

- Inflammatory boweI diseases and hepatitis C virus infection

- Radiofrequency ablation, heat shock protein 70 and potential anti-tumor immunity in hepatic and pancreatic cancers: a minireview

- Outcome of hepatocellular carcinoma treated by liver transplantation: comparison of living donor and deceased donor transplantation

- Norcantharidin inhibits growth of human gallbladder carcinoma xenografted tumors in nude mice by inducing apoptosis and blocking the cell cycle in vivo

- Meetings and Courses