权力接近−抑制行为理论:基于元分析的理论拓展

2025-02-14卫旭华焦文颖

摘" 要" 权力接近−抑制行为理论是解释权力和行为关系的重要理论, 但应用该理论的实证研究却存在与理论相矛盾的结论。通过对2003~2023年探索权力与接近和抑制行为关系的154篇文献、245个实证样本的261个效应值的元分析整合, 本研究检验了权力与接近−抑制行为关系的双刃剑作用机制及边界条件, 以期解释以往研究结论不一致的原因。结果显示权力与接近−抑制行为的关系具有双刃剑效应, 客观权力既会通过主观权力间接增加接近行为并减少抑制行为, 也会对抑制行为产生直接的促进作用, 且主观权力对行为的解释力强于客观权力。调节效应结果显示, 权力距离能够加强主观权力对接近行为的正向影响, 并强化主观权力对抑制行为的负向影响。上述结论有助于深化和拓展权力接近−抑制行为理论框架。

关键词" 权力, 权力接近−抑制理论, 元分析, 接近行为, 抑制行为

分类号 "B849: C91

1" 引言

权力(Power)是影响个体情绪和行为的重要因素(Brass amp; Burkhardt, 1993)。目前学界普遍使用权力接近−抑制理论(The approach and inhibition theory of power)来解释权力对个体情绪、认知和行为的影响(卫旭华, 张怡斐, 2023; Keltner et al., 2003)。尽管权力与情绪、认知和行为的关系密不可分, 但学者们对权力与行为关系的关注度更高, 这是因为个体行为往往是最外显、最持续且影响最长远的结果变量(Keltner et al., 2003)。根据权力接近−抑制行为理论, 高权力会激活个体神经机制中的“行为接近系统” (Behavior approach system, BAS), 进而增加接近行为; 而低权力会激活个体神经机制中的“行为抑制系统” (Behavior inhibition system, BIS), 进而增加抑制行为(Cho amp; Keltner, 2020; Keltner et al., 2003)。尽管大量研究应用权力−接近抑制行为理论开展了实证探索, 但结论却存在着不一致。一些研究表明权力会增加不道德行为(Dubois et al., 2015)并减少亲社会行为(蔡一鸣, 2019), 而另一些研究则发现权力会减少自我推销型撒谎行为(Li et al., 2022)和增加亲社会行为(Chen et al., 2022)。

本研究认为造成这些不一致结论的潜在原因有如下三点。首先, 以往权力研究存在概念化的差异。在权力接近−抑制行为理论中, 权力被定义为通过奖励和惩罚来改变他人状态的能力(Keltner et al., 2003)。然而, 权力可以被概念化为主观权力或客观权力(Heller et al., 2023; Körner amp; Schütz, 2024; Smith amp; Galinsky, 2010)。主观权力是指个体在主观层面对资源控制和能够影响他人能力的一种主观感受和体验, 强调主观感觉和认知(Anderson et al., 2012); 而客观权力是指不受主观影响的客观上对资源的控制和影响他人的能力, 是基于个体处于组织中的层级或位置所赋予的(Metin Camgoz et al., 2023), 表明个体真实、客观拥有的权力。这些对权力不同的概念化可能会导致研究结论出现矛盾。其次, 以往相矛盾的结论说明权力可能存在双刃剑效应。以客观权力为例, 如果客观权力被主观所感知到时, 权力会增加接

近行为并减少抑制行为。如果客观权力未被感知到时, 即使客观权力很大, 个体的主观权力感仍然很小, 从而不会表现出更多的接近行为和更少的抑制行为(van Dijke et al., 2018)。然而, 不幸的是, 以往应用权力接近−抑制行为理论的研究未能充分将主客观权力的区分融入其中, 进行系统深入的考察。这一缺失不仅限制了理论本身对于权力现象解释的全面性和精确性, 也忽略了主客观权力在影响个体行为过程中可能展现出的独特作用路径和效果差异。最后, 权力距离差异可能也是造成结论不一致的原因。权力距离反映了权力差异在多大程度上被接受(Hofstede, 2011)。在高权力距离文化下, 个体接受并认可权力的差异, 此时权力的重要性被凸显出来, 权力接近−抑制行为理论的适用性较强; 而在低权力距离文化下, 权力差异会受到质疑及挑战, 导致权力接近−抑制行为理论的适用性有所下降。故权力距离可能是解释权力与行为后果矛盾结论的一个重要边界条件。

基于以上考虑, 本研究通过元分析方法探讨了主客观权力对接近和抑制行为的作用大小和影响机制是否存在差异, 并且通过探索可能的边界条件(即权力距离)试图解释以往研究中不一致结论出现的原因, 以期深化和拓展权力接近−抑制行为理论。

2" 理论基础与研究假设

2.1" 权力接近−抑制行为理论

根据权力接近−抑制行为理论, 接近行为是指能够帮助个体获得与奖励和机会相关的目标的行为, 抑制行为是指包括了个体的警惕行为、检查惩罚情况、回避和抑制反应等一系列与惩罚和威胁信号有关的行为(Cho amp; Keltner, 2020; Keltner et al., 2003)。无论主观还是客观权力, 权力都代表着拥有更多的资源(Galinsky et al., 2015; Ten Brinke amp; Keltner, 2022)。当个体权力较高时, 他们处于一个奖励和回报富足的环境中, 此时个体更易利用自己的优质资源为自己谋得利益(Webster et al., 2022)。同时, 高权力也赋予了个体不受他人干扰和限制的能力, 导致其神经机制中的BAS系统被激活, 提高了其话语权和自由决策权(包艳 等, 2023; Cho amp; Keltner, 2020), 使他们有更多机会以自我为中心随意行事(Giurge et al., 2021), 并做出无视规则和道德甚至损害他人的行为(Kim et"al., 2017)。相反, 权力的降低会导致抑制行为增多。当个体权力较低时, 他们获得的资源较少, 对他人和事件的影响力也较小。低权力个体也更容易受到社会的威胁和惩罚, 导致其神经机制中的BIS系统被激活, 更能意识到社会和他人对自身的约束, 对他人的评价和反应更加敏感(Cho amp; Keltner, 2020), 所以低权力的个体为了保护自己本就不多的资源, 同时规避威胁和惩罚, 往往会采用诸如沉默、退缩和遵从等抑制行为(朱瑜, 谢斌斌, 2018; Foulk et al., 2020)。因此, 权力接近−抑制行为理论认为权力的增加会导致个体采取更多的接近行为, 而权力的减少会导致个体出现更多的抑制行为。

2.2" 主客观权力的作用机制

客观权力和主观权力(或心理权力)通常被视为两种不同类型的权力概念化(Heller et al., 2023; Körner amp; Schütz, 2024; Smith amp; Galinsky, 2010)。客观权力是指个体客观上对资源的控制和影响他人的能力, 表明其真实、客观拥有的权力, 使用一些客观指标(Finkelstein, 1992)或职位衡量, 比如任职年限、董事会规模(马金城 等, 2017)和股权集中度(李艺玮, 2022), 或者直接询问其在组织中的层级或职位(Magni et al., 2022)。与此相反, 主观权力是指个体在主观层面对资源控制和能够影响他人能力的一种主观感受和体验, 是个体的主观感觉和认知(Anderson et al., 2012)。主观权力往往包括权力感、权力感知、参考权、奖赏权等。客观和主观权力分别代表了权力在客观现实中和个体内心感受中的不同方面, 属于权力的两种不同概念化, 二者的比较如表1所示。

虽然主客观权力都属于权力范畴, 都代表个体对有价值资源的不平等的控制(Smith amp; Galinsky,2010), 但二者仍属于不同的概念化。鉴于此, 本研究认为主客观权力与行为之间的作用大小和影响机制存在差异。

就作用大小而言, 客观权力强调组织层级或职位所赋予的权力, 相对更加客观和外在化(Heller et al., 2023), 不一定会被个体所感知到, 进而激发个体大脑神经机制中的行为接近和抑制系统(Keltner et al., 2003)。因此客观权力的作用效果往往会打折扣, 对个体的接近和抑制行为的解释力较差。与之相比, 主观权力更加关注个体的心理感受(Anderson et al., 2012), 更多的是来源于个体内心对自己拥有权力大小的认知, 相对更加主观和内在化。尤其是在主观权力范畴中, 存在着一种不以外部客观存在的资源或职位为基础, 而是以内在自我认知和信念为基础来影响或控制他人的权力, 即内在权力感知(Liang amp; Chang, 2016; Wagers, 2015; Wagers et al., 2021)。内在权力感知意味着个体即使没有客观权力, 但仍具有较高的主观权力感, 进而更容易促使其做出接近行为和减少抑制行为, 故提出如下假设:

假设1a:与客观权力相比, 主观权力对接近行为的正向影响更强。

假设1b:与客观权力相比, 主观权力对抑制行为的负向影响更强。

就影响机制而言, 客观权力对个体行为的影响存在两种路径。第一种路径是客观权力通过主观权力感知对个体的接近和抑制行为产生间接影响(Anderson amp; Berdahl, 2002)。这种影响逻辑意味着客观权力会被个体主观感知到, 即外在权力感知, 指的是个体以外在资源或职位为保障来影响或控制他人, 属于被激活的客观权力(Galinsky et al., 2003; Min amp; Kim, 2013; Wagers, 2015; Wagers et"al., 2021)。客观权力意味着个体拥有更多的资源(Heller et al., 2023), 这些资源会激发个体对自己影响他人或环境的主观认知。这种对自身拥有权力的主观认知和体验又会促进个体做出主动的接近行为来积极追求目标(Galinsky et al., 2015), 并减少以被动、退缩为典型特征的抑制行为。因此, 较高的客观权力会提升个体的主观权力感, 进而导致个体做出更多的接近行为和更少的抑制行为。

第二种路径是客观权力直接对个体行为产生影响。当控制了客观权力通过主观权力影响个体行为的间接路径后, 剩余的客观权力将成为未被个体所觉察到的客观权力, 也就是潜在客观权力或未被激活的客观权力(Galinsky et al., 2003; Min amp; Kim, 2013)。此时, 权力主体尚未意识到自己拥有影响或控制他人的资源。虽然个体拥有较高的客观权力, 但其主观上可能并不认为自己属于高权者。由于主观感知的权力并未保持高水平, 大脑神经机制中的行为接近系统并未被激活(Galinsky et al., 2015; Keltner et al., 2003), 导致此类高客观权力个体不会表现出更多的接近行为和更少的抑制行为, 甚至会由于自己的“无力感” (Anderson et al., 2012; Yu et al., 2022)激活大脑神经机制中的行为抑制系统, 进而减少接近行为并增加抑制行为。上述两条路径意味着客观权力对接近和抑制行为的影响存在双刃剑效应, 客观权力既可以通过主观权力感知间接增加接近行为并减少抑制行为, 也可以通过直接影响路径减少接近行为并增加抑制行为, 故提出如下假设:

假设2a:客观权力会通过主观权力增加接近行为。

假设2b:客观权力会通过主观权力减少抑制行为。

假设2c:在控制了客观权力通过主观权力影响行为的间接路径后, 客观权力会减少接近行为, 并增加抑制行为。

2.3" 权力距离的调节作用

虽然权力接近−抑制行为理论解释了权力与行为的关系, 但仍存在着一些相互矛盾的研究与结论, 尤其是对于权力与不道德行为(Dubois et al., 2015)、建言行为(段锦云 等, 2013; 徐悦 等, 2018)和亲社会行为(Chen et al., 2022)的关系。考虑到这些研究多是在不同文化背景下开展的, 本研究认为权力距离文化是解释以往研究结论不一致的重要调节因素。

根据Hofstede提出的文化模型, 不同国家在权力距离、个人与集体主义、阳刚与阴柔、不确定性规避和长期取向等维度存在很大的差异(Hofstede, 1993, 2011)。其中, 权力距离作为与主观权力最密切相关的一个维度, 在很大程度上影响着权力与行为的关系。权力距离是指人们对社会中权力分配不平等的接受程度。具体而言, 从主观权力与接近行为的关系来看, 以中国为代表的权力距离较高的社会中, 人们尊重并敬畏权力, 很少质疑或挑战权威, 往往秉持着“惟命是从” “尊卑有序, 上下有别”的传统观念(王弘钰, 于佳利, 2022)。相反, 在权力距离较低的社会中, 人们努力追求权力平等, 更倾向于以批判性的态度看待权力, 鼓励对权威提出质疑和挑战(尹奎 等, 2024), 权力往往处于较为透明和被监督的状态下。长此以往, 相比于低权力距离情境, 高权力距离情境下权力赋予个体的自主支配权更大, 这既可能让他们最大程度发挥权力的价值和作用, 也可能让他们觉得权力更不受制约, 使得权力愈发膨胀, 助长不道德行为。这也意味着主观权力对接近行为的正向作用在高权力距离情境下会被加强。

从主观权力与抑制行为的关系来看, 当权力距离较高时, 等级秩序十分森严, 高权者被期望表现权力, 而低权者则更加敬畏权威, 更重视他人的看法和群体的认可(Hofstede, 2011), 尽力避免潜在的冲突和矛盾, 更倾向于表现出规避不确定性和风险的抑制行为。此时, 低权者挑战权威可能面临更高的风险, 他们表达自我的阻力被加大, 更容易表现出沉默和退缩等抑制行为。与此相反, 当权力距离较低时, 整体的权力差距较小, 人们倾向于接受权力的平等分配, 不惧向高权者提出挑战(Hofstede, 2011)。同时, 在权力距离较低的情境下, 高权者通常允许不同的声音和观点出现, 对分歧和争论的包容性也更强(王弘钰, 于佳利, 2022), 此时低权者表达自我的通道更为顺畅, 认为自己能够改变现状的可能性和信心也更大, 因此也更不容易采取回避和顺从等抑制行为。综上, 本文提出如下假设:

假设3a:权力距离调节了主观权力与接近行为之间的关系。当权力距离越高时, 主观权力对接近行为的正向影响越强。

假设3b:权力距离调节了主观权力与抑制行为之间的关系。当权力距离越高时, 主观权力对抑制行为的负向影响越强。

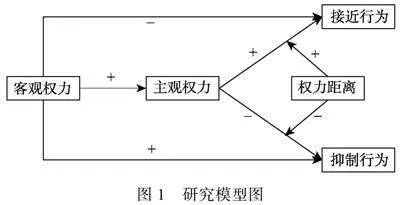

本研究的理论模型如图1所示。

3" 研究方法

3.1" 文献查找

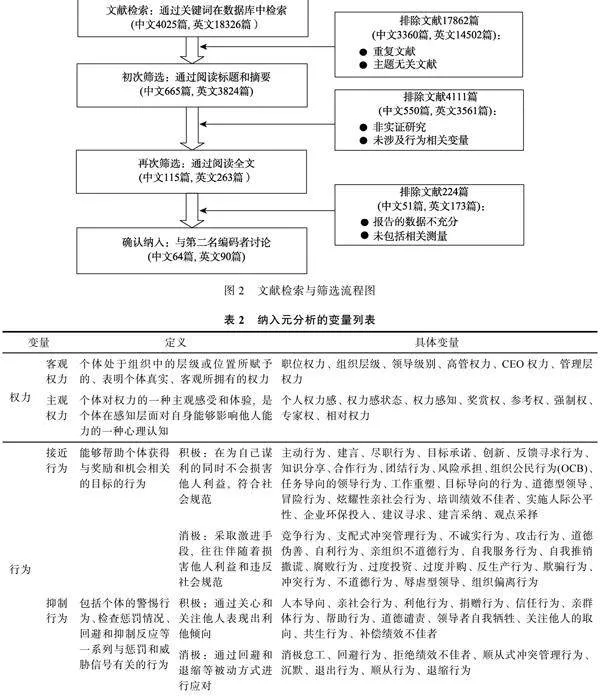

鉴于权力接近−抑制理论首次提出的时间为2003年, 所以将文献的发表时间限定为2003年1月~2023年12月。中文文献主要在中国知网进行搜索。为减少发表偏差, 涵盖的文献类型包括期刊论文、硕博论文及会议论文, 以权力/行为、权力/接近/抑制为关键词进行检索, 初步检索到4025篇文献(包括期刊827篇、硕博论文3197篇及会议1篇)。英文文献主要在Web of Science核心合集和Google Scholar两个数据库中进行查找, 以power/behavior、power/approach/inhibit为关键词进行检索。同时, 通过EBSCO、Elsevier、Springer和Wiley数据库进行了查漏补缺, 初步检索到18326篇文献。

首轮文献查找共找到22351篇中英文论文。接下来, 按照如下标准对论文进行筛选:(1)必须为实证研究; (2)采用量化方法衡量主要变量; (3)论文涉及行为变量; (4)论文报告了相关的效应值(相关系数r或者可转换的统计量F、t、d、M和SD等); (5)重复样本仅使用一次。文献查找由两名研究者单独进行, 之后进行讨论并汇总, 得到最终的文献样本。按照这5个标准共筛选出154篇文献(64篇中文和90篇英文文献), 包括245个样本, 合计261个效应值, 样本主要来自中国、美国、荷兰、澳大利亚、以色列、比利时、德国、英国、加拿大、芬兰、波兰、印度、马来西亚、泰国、土耳其等。具体文献检索与筛选过程如图2所示。

3.2" 变量编码

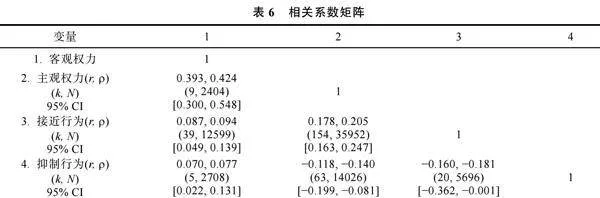

本研究收集了权力和个体行为二者之间的效应值(各变量定义及编码见表2)。权力包括客观权力和主观权力。客观权力是指个体真实、客观所拥有的权力。当文献中表述为职位权力、组织层级、高管权力、CEO权力等时编码为客观权力。主观权力是指个体对影响他人的能力的一种心理感知(Anderson et al., 2012)。当文献中表述为个人权力感、权力感知、奖赏权、参考权等时, 或是在测量或操纵权力时使用Anderson等(2012)编制的一般权力感量表、采用回忆启动法(Galinsky et"al., 2003; Wiltermuth amp; Flynn, 2013)、词语搜索法(陈天华, 2021; Smith amp; Trope, 2006)、使用Schaerer等(2015)编制的权力感量表、Yukl和Falbe (1991)编制的职位权力量表、Yu等(2019)编制的感知权力量表以及采用角色扮演法(陈天华, 2021; Galinsky et al., 2003)的编码为主观权力。

个体行为涉及到的变量较多, 因此本文根据Keltner等(2003)的权力接近−抑制理论的相关研究, 将所有行为归类为接近行为和抑制行为两大类。接近行为既包括积极的又包括消极的(Nikitin amp; Freund, 2010; Puleo, 2020), 积极的主要有建言、创新、知识分享、主动行为等, 消极的主要有竞争、不诚实、攻击、自利行为等。抑制行为也分为积极的和消极的两类(Nikitin amp; Freund, 2010; Puleo, 2020)。积极的包括人本导向、利他、助人、亲社会行为等, 消极的包括消极怠工、沉默、退缩、顺从行为等。本研究邀请了四名心理学领域的研究者对个体行为进行了归类, 结果显示四名研究者之间具有较高的评定者一致性(Fleiss Kappa = 0.851, p lt; 0.001)。最终纳入了61个行为变量, 其中接近行为41个, 抑制行为20个。

调节变量为权力距离。权力距离根据Hofstede提出的权力距离指数(PDI)进行衡量。涉及的18个国家的权力距离指数分别为马来西亚(104)、中国(80)、斯里兰卡(80)、印度(77)、新加坡(74)、波兰(68)、土耳其(66)、比利时(65)、泰国(64)、巴基斯坦(55)、美国(40)、加拿大(39)、荷兰(38)、澳大利亚(36)、英国(35)、德国(35)、芬兰(33)、以色列(13)。

变量编码过程由两名研究者独立进行, 首轮编码一致性比例为85.7%, 之后对不一致的编码进行讨论、修正。除此以外, 还借助了AI工具(文心一言和ChatGPT-4o mini)进行辅助编码, 最终得到一致的编码结果。当遇到一个研究样本同一个变量出现多种测量时, 我们进行了效应值整合, 以降低人为增加样本量而造成的偏差(卫旭华 等, 2018; Joshi amp; Roh, 2009)。同时, 收集了主观测量变量的信度系数, 用于后续元分析的测量误差修正。

3.3" 元分析过程

本研究使用Smart meta-analysis (SMA) 1.1 (Wei, 2024)、Mplus 8.3等软件进行数据分析。本研究通过漏斗图及失安全系数来衡量所纳入论文的发表偏差问题。结果显示, 各组效应值大体上围绕均值呈对称分布, 且大部分显著效应值的失安全系数均满足5k + 10的标准(见表3和表4), 说明发表偏差问题并不严重。对于失安全系数不满足5k + 10标准的效应值, 本研究使用剪补法进行了校正。在主客观权力对行为方差贡献度方面, 通过相对权重分析对主客观权力影响两种行为的作用大小进行检验。对于中介效应分析, 本研究首先对所有焦点文献(即权力和行为的相关文献)中报告的效应值进行了编码, 既包括焦点关系效应值(客观权力/主观权力与接近/抑制行为), 也包括非焦点关系效应值(客观权力与主观权力、接近行为与抑制行为), 并用这些信息形成初步的相关系数矩阵(Bai et al., 2024; Podsakoff et al., 2007)。其次, 借鉴以往部分学者的做法(Chung et al., 2022), 本研究也检索了以往元分析中是否存在非焦点关系(即接近行为与抑制行为、主观权力与客观权力)的效应值, 以作为相关系数矩阵的补充数据。随后, 本研究运用Mplus 8.3 进行了元分析结构方程建模(MASEM), 分析客观权力通过主观权力对接近和抑制行为的影响。

关于模型选择方面, 固定效应模型假设不同研究的实际效果是相同的, 其结果之间的差异仅由随机误差引起; 而随机效应模型则假设不同研究的实际效果可能不同, 且这种不同不仅仅受随机误差影响, 还受不同样本或不同测量方式的影响(Borenstein et al., 2021; Schmidt et al., 2009)。在权力与行为的实证研究中, 样本和测量工具选取的不同都会影响研究结果, 故应选择随机效应模型进行分析。此外, 从统计学角度来说, 如果各效应值之间的异质性较高, 即Q统计量所对应的p值显著或者I2值较高, 研究也应选择随机效应模型。结果显示, 所有变量间的Q值均达到了显著性水平, 且I2均大于60% (Higgins amp; Thompson, 2002), 这也表明各效应值之间存在较高的异质性(如表3和表4所示), 故选择随机效应模型更为科学合理。关于结果报告方面, 本研究不仅报告了未经测量误差修正的相关系数r, 而且也报告了经过信度测量误差修正的真实相关系数r及其95%置信区间。

4" 结果分析

4.1" 主客观权力作用大小分析

首先, 表3展示了权力与接近和抑制行为的关系。权力对积极接近(r = 0.213, p lt; 0.001)、消极接近(r = 0.192, p lt; 0.001)及整体接近行为的影

响均显著为正(r = 0.204, p lt; 0.001)。权力对积极抑制行为的影响边际显著为负(r = −0.074, p = 0.063), 对消极抑制(r = −0.237, p lt; 0.001)和整体抑制行为的影响显著为负(r = −0.141, p lt; 0.001)。这与权力接近−抑制行为理论的假设相符。

其次, 对主客观权力对接近和抑制行为的具体效应值进行分析, 结果如表4所示。客观(r = 0.093, p lt; 0.001)和主观权力(r = 0.233, p lt; 0.001)对接近行为的影响均显著为正, 主观权力对抑制行为的影响显著为负(r = −0.160, p lt; 0.001), 而客观权力对抑制行为的影响显著为正(r = 0.088, p lt; 0.01)。初步可以看出, 相比于客观权力, 主观权力对接近行为的正向影响更强, 对抑制行为的负向影响更强。

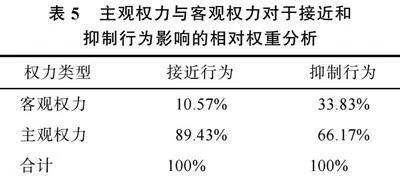

再次, 通过相对权重分析(Tonidandel amp; LeBreton, 2015)检验了主客观权力对接近和抑制行为作用大小的差异。表5结果表明, 主观权力无论是在预测接近行为还是抑制行为方面, 都占据更大的解释方差。具体而言, 在接近行为方面, 主观和客观权力分别解释了89.43%和10.57%的方差, 假设1a得到验证。在抑制行为方面, 主观和客观权力分别解释了66.17%和33.83%的方差, 假设1b得到验证。

4.2" 作用机制分析

通过元分析结构方程模型对客观权力通过主观权力对接近和抑制行为的间接影响进行了分析。首先, 对两两变量间的相关系数进行估计, 形成相关系数矩阵(如表6所示); 其次, 基于相关系数矩阵和样本量调和平均数进行结构方程建模(Hunter amp; Schmidt, 2004; Viswesvaran amp; Ones, 1995), 得到元分析结构方程模型的路径分析结果(如图3所示)。该模型为饱和模型(saturated model), 拟合效果良好(RMSEA = 0.00, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00)。

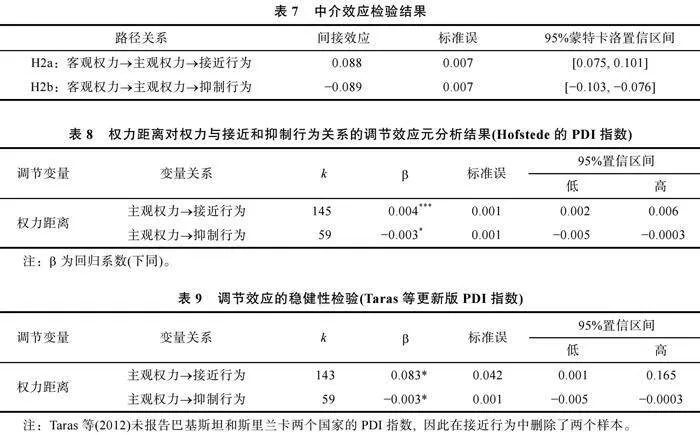

中介分析结果如表7所示, 客观权力通过主观权力与接近行为的间接效应是0.088, 95% CI = [0.075, 0.101], 假设2a得到验证。客观权力通过主观权力与抑制行为的间接效应是−0.089, 95% CI = [−0.103, −0.076], 假设2b得到验证。除此以外, 图3路径分析结果显示, 客观权力对接近行为的直接效应不显著(β = 0.06, 95% CI = [−0.023, 0.035]), 客观权力对抑制行为的直接效应显著为正(β = 0.166, 95% CI = [0.137, 0.195]), 假设2c得到部分验证。

4.3" 调节效应分析

表8显示了Hofstede的权力距离指数(PDI)对主观权力与接近或抑制行为之间关系的调节作用。无论是主观权力对接近行为还是对抑制行为, 权力距离都显著调节了二者的关系。当权力距离越高时, 权力与接近行为的正向关系越强(b = 0.004, p lt; 0.001), 假设3a得到验证。当权力距离越低时, 权力与抑制行为的负向关系也越强(b = −0.003, p lt; 0.05), 假设3b得到验证。

此外, 鉴于Hofstede的PDI指数提出时间较早, 其时效性可能有所减弱, 本研究借鉴Taras等(2012)的更新版PDI指数对调节效应结果进行了稳健性检验。表9元回归结果显示, 当权力距离越高时, 权力与接近行为之间的正向关系越强(b"= 0.083, p lt; 0.05), 权力与抑制行为之间的负向关系也越强(b = −0.003, p lt; 0.05), 验证了假设3a和3b的稳健性。

5" 讨论

5.1" 理论贡献

首先, 本研究验证并拓展了权力接近−抑制行为理论的相关命题。虽然已有大量实证研究检验了该理论(卫旭华, 张怡斐, 2023; Luo et al., 2023), 但仍存在一些与理论矛盾的结论。本研究通过元分析方法整合以往实证结果, 验证了权力会增加接近行为并减少抑制行为。此外, 本研究通过区分主客观权力对接近和抑制行为产生的不同影响, 明确了主客观权力对两种行为的解释力差异, 即无论是接近行为还是抑制行为, 主观权力对行为的解释力都强于客观权力, 拓展了不同类型权力与行为的真实关系。

其次, 本研究探究了主客观权力对行为的影响机制的差异(见图4), 在一定程度上解释了以往研究结论不一致的原因, 进一步深化和拓展了权力接近−抑制行为理论。在提出该理论时, Keltner等(2003)对权力的界定较为笼统, 在具体论述中既涉及客观权力又涉及主观权力, 似乎表明这两种权力都适用该理论且作用大小一样, 导致理论对权力现象解释力的下降。本研究正是基于这一不足, 将主客观权力的区分引入该理论的分析框架, 旨在探究两者在该理论背景下的适配度与差异性。研究结果显示, 主客观权力在作用于权力接近与抑制机制时, 确实呈现出不同的模式与效果。具体而言, 客观权力需要通过主观权力间接增加接近行为并减少抑制行为, 揭示主观权力作为连接客观权力与行为的桥梁作用。

本研究结果也进一步表明在控制了客观权力通过主观权力影响行为的间接路径后, 客观权力对接近行为的直接影响是不显著的, 其对抑制行为会产生积极的促进作用。这似乎与权力接近−抑制行为理论的预期假设有所出入, 但进一步思考可以发现, 这恰恰从另一个角度细化、拓展了该理论。也就是说, 当客观权力被主观所感知到时(即外在权力感知或激活的客观权力), 此时个体基于拥有的资源而激活了个体对自己影响他人或环境的主观认知, 进而会增加接近行为并减少抑制行为。当客观权力未被感知到时(即潜在客观权力或未被激活的客观权力), 即使客观权力很高, 个体的主观权力感仍然很低, 个体可能因为缺乏自我认知并不会认为自己是高权力者, 因此不一定会做出接近行为或减少抑制行为。这也解释了为什么一些客观权力看似较高的个体也会做出他人取向的抑制行为(陈明淑, 陆擎涛, 2019; Baruch et al., 2004)。此外, 如果个体的客观权力很低但其主观权力感很高时(即内在权力感知), 他们以内在自我认知和信念为基础来影响或控制他人, 几乎不受外部权力影响, 并认为自己属于高权力者, 因此依然会表现出较高的接近行为和较低的抑制行为。这也解释了一些职位不高的个体为什么也会表现出较高的接近行为和较少的抑制行为(van Dijke et al., 2018)。这一发现不仅证实了主客观权力在适用该理论时存在差异, 更凸显了在该理论框架下区分这两种权力的必要性和重要性。

最后, 本研究发现权力距离在主观权力与接近或抑制行为之间的调节作用, 扩展了该理论的边界条件。Keltner等(2003)在构建权力接近−抑制行为理论时也提出权力距离可能对权力与行为之间的关系存在潜在的调节作用。然而, 由于地域或资源等因素的限制, 以往实证研究往往只能聚焦一个或少数几个国家或地区, 样本有限, 无法系统性地研究大样本下不同权力距离文化对权力接近−抑制理论的影响。本研究通过元分析方法发现权力距离的确能够起到调节作用, 即当权力距离越大时, 主观权力对接近行为的正向影响和对抑制行为的负向影响都更强, 说明了在不同的权力距离下, 主观权力与接近或抑制行为之间的关系的确存在显著差异。

5.2" 实践启示

第一, 组织管理者应认识到主客观权力产生的不同影响。本研究结果表明, 客观权力需要通过主观权力增加接近行为并减少抑制行为。这说明只有当个体的主观权力较高时, 才会做出符合权力接近−抑制行为理论预期的行为。如果仅仅提高了个体的客观权力而主观权力未被激活, 个体自身可能并未感觉到较高的权力水平, 此时权力可能不会发挥预期的效果。因此, 组织及管理者需要意识到客观权力并不等于主观权力, 以及主观权力在连接客观权力与行为中的重要性, 通过提高主观权力进而发挥权力的最大效用。

第二, 组织管理者需要考虑权力距离等文化因素对权力和行为之间关系的影响。本研究结果发现, 高权力距离下主观权力对接近行为的正向影响和对抑制行为的负向影响都更强。这说明了高权力距离背景下, 组织中的高权者更加不受约束, 更加自信和大胆, 而低权者更加沉默和被动。因此, 在高权力距离下, 权力监督者更应该提高警惕, 通过一系列合理有效的监管机制, 评估和规范权力, 减少权力无制约地膨胀, 提高权责透明度。除此以外, 组织还应努力打通上下沟通渠道, 适度调整和改变等级制度森严的体系, 降低高权力距离下员工对权威的崇尚, 鼓励他们畅所欲言、敢于挑战和质疑权威。

5.3" 局限性与未来展望

首先, 元分析是以大量文献作为基础的, 尽管本研究已经尽可能地搜集到较多符合要求的文献, 但由于受到工具和语言等条件的限制, 可能遗漏了一些文献和数据, 研究结果可能会受到一定影响。未来研究可以进一步扩大样本量, 纳入更多语言和不同来源的研究文献。

其次, 本研究仅仅探讨并验证了权力接近−抑制理论中有关行为部分的相关假设。然而该理论还包含情绪、认知等方面的相关命题, 尤其是情绪又与行为密切相关, 积极或消极情绪与本研究中提出的积极/消极接近行为和积极/消极抑制行为之间是否存在关联, 而权力对情绪的体验和表达又产生何种影响(Van Kleef amp; Lange, 2020)。未来研究可以继续检验该理论中的其他命题, 或者系统完整地检验全部理论命题, 为该理论提供更加有力的证据支持。

再次, 在检验客观权力通过主观权力影响抑制行为的关系中, 符合条件的效应值的数量较少, 仅有5篇文献探讨了客观权力与抑制行为的关系, 可能在一定程度上影响分析结果的稳健性。因此, 未来研究可以继续探索本研究的相关假设, 增强研究和理论的准确性和有效性。

最后, 本研究只考虑了权力距离在主观权力和行为之间的调节作用, 还存在许多其他潜在的调节变量。比如, 学者们可以从权力合法性的角度探讨权力和行为的边界条件。一些研究表明地位(Gu et al., 2020; Jin et al., 2021)、能力或胜任力是决定权力影响机制的重要合法性前提(Amedu amp; Dulewicz, 2018)。因此, 未来研究可以探讨地位或胜任力是否在权力和行为关系间发挥调节作用, 进一步扩展权力接近−抑制理论。

参考文献

注:*表示该文献被用于元分析。

包艳, 马伟博, 赵海涛. (2023). 领导成员交换关系差异对团队绩效的影响: 团队情绪抑制氛围与领导权力感的作用. 中国人力资源开发, 40(8), 67−81.

*蔡一鸣. (2019). 权力感和道德自我形象对亲社会行为的影响 [硕士学位论文]. 暨南大学, 广州.

*陈超宇. (2023). 权力对建议采纳的影响机制 [硕士学位论文]. 天津大学.

*陈明淑, 陆擎涛. (2019). 员工助人行为与工作幸福感关系研究——以团队凝聚力为调节. 贵州财经大学学报, (5), 54−64.

*陈秋菊. (2021). 权力感和权力距离信念对攻击行为的影响 [硕士学位论文]. 华东师范大学, 上海.

*陈天华. (2021). 地位威胁对员工亲组织不道德行为的影响 [硕士学位论文]. 兰州大学.

*段锦云, 黄彩云. (2013). 个人权力感对进谏行为的影响机制:权力认知的视角. 心理学报, 45(2), 217−230.

*段锦云, 凌斌, 王雨晨. (2013). 组织类型与员工建言行为的关系探索: 基于权力的视角. 应用心理学, 19(2), 152−162.

*樊耘, 陈倩倩, 吕霄. (2015). LMX对员工反馈寻求行为的影响机制研究——基于分配公平和权力感知的视角. 科学学与科学技术管理, 36(10), 158−168.

*高中华, 丁佳琦, 徐燕, 刘琪. (2022). 公平领导行为对员工知识共享行为的影响机制——基于地位竞争动机的中介作用和个体相对剥夺感的调节作用. 技术经济, 41(6), 164−175.

*郭亚康. (2020). 权力感与道德认同对道德伪善的影响 [硕士学位论文]. 山东师范大学, 济南.

*焦学赛, 于海云. (2024). 技术过载对员工创新行为的影响研究——基于工作倦怠的中介作用和授权型领导的调节作用. 经营与管理, (7), 152−160.

*李旭洋. (2017). 环境不确定性、高管权力与风险承担 [硕士学位论文]. 内蒙古大学, 呼和浩特.

*李艺玮. (2022). 媒体关注、管理层权力与企业环保投入——基于重污染行业上市公司的实证研究. 商业会计, (3), 33−38.

*梁子笑. (2022). 员工绩效对建言行为的影响研究 [硕士学位论文]. 浙江工商大学, 杭州.

*刘凡, 郑鸽, 赵玉芳. (2018). 权力对压力应对行为倾向的影响:认知评估的中介作用. 心理科学, 41(4), 890−896.

*刘明伟, 王华英, 李铭泽. (2020). 自以为是所以主动改变?员工自恋与主动变革行为的关系研究. 中国人力资源开发, 37(2), 21−33.

*刘明霞, 徐心吾. (2021). 真实型领导、主管认同与员工知识共享行为:程序公平的调节作用. 湖南大学学报(社会科学版), 35(1), 45−53.

*刘善仕, 玉胜贤, 刘嫦娥. (2024). 投桃报李:临时员工助人行为对正式员工隐性知识分享的影响机制. 商业经济与管理, (6), 54−67.

*刘松博, 程进凯, 马晓颖. (2023). 资质过剩感对员工组织公民行为的正面影响——领导涌现的中介作用. 软科学, 37(4), 101−108.

*刘小庆. (2016). 权力对员工沉默的接近—抑制效应 [硕士学位论文]. 华中师范大学, 武汉.

*罗远淑. (2021). 敬畏对不诚实行为的影响:权力感的中介作用 [硕士学位论文]. 四川师范大学, 成都.

*骆皓爽, 何雪菲, 王晓庄. (2016). 绩效考核满意度对工作退缩行为的影响:有调节的中介效应. 心理与行为研究, 14(6), 817−825.

*马金城, 张力丹, 罗巧艳. (2017). 管理层权力、自由现金流量与过度并购——基于沪深上市公司并购数据的实证研究. 宏观经济研究, (9), 31−40.

*马静. (2020). 员工组织地位与其态度和行为关系:有调节的中介作用 [硕士学位论文]. 河南大学, 开封.

*孟庆飞. (2015). 员工个人权力感知对其工作表现的影响机制研究 [硕士学位论文]. 河南大学, 开封.

*牛楠, 刘兵, 李嫄. (2020). 边界管理者权力感对团队冲突管理行为的影响研究. 现代财经(天津财经大学学报), 40(7), 71−84.

*容琰, 杨百寅, 隋杨. (2016). 权力感对员工建言行为的影响——自我验证机制的作用. 科学学与科学技术管理, 37(10), 119−129.

*申晨, 马静, 王明辉. (2021a). 欲戴皇冠必承其重: 地位-权力匹配对员工工作行为的影响. 中国人力资源开发, 38(7), 48−59.

*申晨, 马静, 王明辉. (2021b). 员工地位如何影响其工作态度和行为?权力感知的中介作用和自我监控的调节作用. 心理研究, 14(2), 138−146.

*宋晓雯. (2019). 权力感与心理距离对风险决策的影响研究 [硕士学位论文]. 鲁东大学, 烟台.

*孙麟惠. (2019). 个体权力感水平与自利倾向的关系研究 [硕士学位论文]. 浙江大学, 杭州.

*孙鹏. (2022). 权力感对利他行为的影响:中介效应及调节效应分析 [硕士学位论文]. 山东师范大学, 济南.

*谭洁. (2012). 权力感知匹配的行为接近—抑制效应 [硕士学位论文]. 浙江大学, 杭州.

王弘钰, 于佳利. (2022). 权力感对越轨创新的影响机制研究——基于中国本土文化的解释. 现代财经(天津财经大学学报), 42(4), 3−19.

*王君瑜, 韦欢丹, 迟立忠. (2022). 时间压力与权力感对合作行为的影响——基于囚徒困境博弈合作任务. 第二十四届全国心理学学术会议, 中国河南新乡.

*王磊, 邢志杰. (2019). 权力感知视角下的双元威权领导与员工创新行为. 管理学报, 16(7), 987−996.

*王仁瑾. (2022). 权力感对博弈情境中合作行为的影响及促进研究 [硕士学位论文]. 陕西师范大学, 西安.

*王三银, 王冬冬, 陶颖. (2022). 工作-家庭增益对称性对员工建言的影响. 中国人力资源开发, 39(8), 43−57.

*王雁飞, 陈雪玲, 郑立勋, 朱瑜. (2024). 领导建言寻求对员工主动行为的作用机制研究. 管理学报, 21(6), 840−852.

*王雁飞, 李楠, 郑立勋, 朱瑜. (2024). 游戏化人力资源管理实践对员工创新行为的影响作用机理研究. 中国人力资源开发, 41(7), 6−20.

*王雁飞, 林珊燕, 郑立勋, 朱瑜. (2022). 社会信息加工视角下伦理型领导对员工创新行为的双刃剑影响效应研究. 管理学报, 19(7), 1006−1015.

*王垚, 李小平. (2015). 不同人际关系取向下的权力对利他行为的影响. 心理与行为研究, 13(4), 516−520.

卫旭华, 王傲晨, 江楠. (2018). 团队断层前因及其对团队过程与结果影响的元分析. 南开管理评论, 21(5), 139−149+187.

*卫旭华, 张怡斐. (2023). 权力对组织成员竞争行为的影响:被调节的中介模型. 系统管理学报, 32(1), 141−153.

*谢江佩, 戴馨, 黎常. (2020). 团队成员权力感知对建言行为的影响研究. 科研管理, 41(7), 201−209.

*谢玮. (2020). 审计质量、管理层权力对高管腐败影响的实证研究 [硕士学位论文]. 山东农业大学, 泰安.

*徐悦, 段锦云, 王雨晨. (2018). 权力感与进谏:进谏效能感的中介机制研究. 应用心理学, 24(1), 62−70+61.

*许龙, 孟华兴. (2021). 高绩效工作系统感知促进员工建言行为:链式中介效应分析. 经济与管理, 35(4), 84−92.

*杨红玲, 赵李晶, 刘耀中, 倪亚琨. (2018). 权力感让领导者更自利:自恋人格和信任倾向的调节作用. 中国人力资源开发, 35(12), 68−79.

*姚琦, 吴章建, 张常清, 符国群. (2020). 权力感对炫耀性亲社会行为的影响. 心理学报, 52(12), 1421−1435.

尹奎, 迟志康, 董念念, 李培凯, 赵景. (2024). 团队反思与团队资源开发、利用及团队结果的关系:一项元分析. 心理科学进展, 32(2), 228−245.

*云祥, 李小平. (2012). 权力会导致欺骗吗? 心理研究, 5(6), 40−43.

*詹小慧, 李群, 杨东涛. (2019). LMX差异化对反生产行为的影响——基于跨层次的调节效应. 山西财经大学学报, 41(1), 87−97.

*张超, 陈冰, 赵玉芳. (2022). 社会排斥促进亲群体行为意向:权力感的调节作用. 心理科学, 45(6), 1428−1435.

*张恩涛, 王硕. (2020). 权力和地位对信任行为的影响. 心理科学, 43(2), 460−465.

*张利君. (2019). 会计稳健性、管理层权力与企业过度投资——基于能源类上市公司面板数据的实证研究. 预测, 38(3), 58−63.

*张玲玲. (2021). 顾客导向氛围对员工主动行为的影响研究. 财经问题研究, (9), 121−129.

*章慧南, 胡嘉慧, 曲如杰. (2020). 共享型领导对员工建言行为的影响——员工权力感的中介作用. 技术经济, 39(7), 184−192.

*赵红丹, 陈元华. (2022). 社会责任型人力资源管理如何降低员工亲组织非伦理行为:道德效力和伦理型领导的作用. 管理工程学报, 36(6), 57−67.

*赵占恒. (2018). 管理权力、社会身份与企业高管腐败——基于中国上市公司的实证研究. 郑州轻工业学院学报(社会科学版), 19(4), 73−80.

*周秉, 张苏串. (2024). 组织面子文化对员工亲组织非伦理行为的跨层“双刃”效应研究. 企业经济, 43(7), 60−70.

*周念华, 余明阳, 辛杰. (2021). 感知的企业社会责任对员工创新行为作用机制的实证研究. 研究与发展管理, 33(6), 111−123.

*周天爽, 潘玥杉, 崔丽娟, 杨莹. (2020). 权力感与助人行为:社会距离的中介和责任感的调节. 心理科学, 43(5), 1250−1257.

*周媛媛. (2020). 权力感对不诚实行为的影响:观点采择的中介和受益对象的调节作用 [硕士学位论文]. 四川师范大学, 成都.

*周珍珍. (2017). 员工个人权力感知与员工沉默行为的关系研究 [硕士学位论文]. 华中师范大学, 武汉.

*朱静. (2016). 权力感对建议寻求的影响:自信的中介和谦卑的调节作用 [硕士学位论文]. 苏州大学.

*朱瑜, 谢斌斌. (2018). 差序氛围感知与沉默行为的关系:情感承诺的中介作用与个体传统性的调节作用. 心理学报, 50(5), 539−548.

*Ali, H., Mahmood, A., Ahmad, A., amp; Ikram, A. (2021). Humor of the leader: A source of creativity of employees through psychological empowerment or unethical behavior through perceived power? The role of self-deprecating behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 635300.

Amedu, S., amp; Dulewicz, V. (2018). The relationship between CEO personal power, CEO competencies, and company performance. Journal of General Management, 43(4), 188−198.

Anderson, C., amp; Berdahl, J. L. (2002). The experience of power: Examining the effects of power on approach and inhibition tendencies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1362−1377.

*Anderson, C., amp; Galinsky, A. D. (2006). Power, optimism, and risk-taking. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36(4), 511−536.

Anderson, C., John, O. P., amp; Keltner, D. (2012). The personal sense of power. Journal of Personality, 80(2), 313−344.

*Aziz, R. A., Noranee, S., Hassan, N., Hussein, R., amp; Jacob, G. A. D. (2021). The influence of leader power on interpersonal conflict in the workplace. Journal of International Business, Economics and Entrepreneurship, 6(1), 87−93.

Bai, J., Su, J., Xin, Z., amp; Wang, C. (2024). Calculative trust, relational trust, and organizational performance: A meta-analytic structural equation modeling approach. Journal of Business Research, 172, 114435.

*Baruch, Y., O'Creevy, M. F., Hind, P., amp; Vigoda-Gadot, E. (2004). Prosocial behavior and job performance: Does the need for control and the need for achievement make a difference? Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 32(4), 399−411.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P., amp; Rothstein, H. R. (2021). Introduction to meta-analysis. John Wiley amp; Sons.

Brass, D. J., amp; Burkhardt, M. E. (1993). Potential power and power use: An investigation of structure and behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 36(3), 441−470.

*Brockner, J., De Cremer, D., van Dijke, M., De Schutter, L., Holtz, B., amp; Van Hiel, A. (2021). Factors affecting supervisors' enactment of interpersonal fairness: The interactive relationship between their managers' informational fairness and supervisors' sense of power. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 42(6), 800−813.

*Chen, S. C., Zou, W. Q., amp; Liu, N. T. (2022). Leader humility and machiavellianism: Investigating the effects on followers' self-interested and prosocial behaviors. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 742546.

*Cheng, Y.-N., Hu, C., Wang, S., amp; Huang, J.-C. (2024). Political context matters: A joint effect of coercive power and perceived organizational politics on abusive supervision and silence. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 41(1), 81−106.

Cho, M., amp; Keltner, D. (2020). Power, approach, and inhibition: Empirical advances of a theory. Current Opinion in Psychology, 33, 196−200.

Chung, S., Zhan, Y., Noe, R. A., amp; Jiang, K. (2022). Is it time to update and expand training motivation theory? A meta-analytic review of training motivation research in the 21st century. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(7), 1150−1179.

*De Wit, F. R., Scheepers, D., Ellemers, N., Sassenberg, K., amp; Scholl, A. (2017). Whether power holders construe their power as responsibility or opportunity influences their tendency to take advice from others. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(7), 923−949.

*DeCelles, K. A., DeRue, D. S., Margolis, J. D., amp; Ceranic, T. L. (2012). Does power corrupt or enable? When and why power facilitates self-interested behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(3), 681−689.

*Dissanayake, D. S., amp; Jayawardana, A. K. (2023). The impact of personal sense of power on unethical decision- making: A moderated mediation model of love of money motive and power distance orientation. Decision, 50(1), 19−34.

*Dubois, D., Rucker, D., amp; Galinsky, A. (2015). Social class, power, and selfishness: When and why upper and lower class individuals behave unethically. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(3), 436−449.

*Ferguson, A. J., Ormiston, M. E., amp; Moon, H. (2010). From approach to inhibition: The influence of power on responses to poor performers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(2), 305−320.

Finkelstein, S. (1992). Power in top management teams: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 35(3), 505−538.

*Foulk, T. A., De Pater, I. E., Schaerer, M., du Plessis, C., Lee, R., amp; Erez, A. (2020). It's lonely at the bottom (too): The effects of experienced powerlessness on social closeness and disengagement. Personnel Psychology, 73(2), 363−394.

Galinsky, A. D., Gruenfeld, D. H., amp; Magee, J. C. (2003). From power to action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(3), 453−466.

Galinsky, A. D., Rucker, D. D., amp; Magee, J. C. (2015). Power: Past findings, present considerations, and future directions. In APA handbook of personality and social psychology, Vol. 3. Interpersonal relations. (pp. 421−460). American Psychological Association.

*Gilad, C., amp; Maniaci, M. R. (2022). The push and pull of dominance and power: When dominance hurts, when power helps, and the potential role of other-focus. Personality and Individual Differences, 184, 111159.

*Giurge, L. M., Van Dijke, M., Zheng, M. X., amp; De Cremer, D. (2021). Does power corrupt the mind? The influence of power on moral reasoning and self-interested behavior. The Leadership Quarterly, 32(4), 101288.

*Gu, Z., Liu, L., Tan, X., Liang, Y., Dang, J., Wei, C., ... Wang, G. (2020). Does power corrupt? The moderating effect of status. International Journal of Psychology, 55(4), 499−508.

*Hershcovis, M. S., Neville, L., Reich, T. C., Christie, A. M., Cortina, L. M., amp; Shan, J. V. (2017). Witnessing wrongdoing: The effects of observer power on incivility intervention in the workplace. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 142, 45−57.

Heller, S., Ullrich, J., amp; Mast, M. S. (2023). Power at work: Linking objective power to psychological power. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 53(1), 5−20.

*Hiemer, J., amp; Abele, A. E. (2012). High power= motivation? Low power= situation? The impact of power, power stability and power motivation on risk-taking. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(4), 486−490.

Higgins, J. P. T., amp; Thompson, S. G. (2002). Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 21(11), 1539−1558.

Hofstede, G. (1993). Cultural constraints in management theories. Academy of Management Perspectives, 7(1), 81−94.

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 1−26.

*Hoogervorst, N., De Cremer, D., van Dijke, M., amp; Mayer, D. M. (2012). When do leaders sacrifice?: The effects of sense of power and belongingness on leader self-sacrifice. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(5), 883−896.

*Huang, C., Tian, S., Wang, R., amp; Wang, X. (2022). High- level talents' perceive overqualification and withdrawal behavior: A power perspective based on survival needs. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 921627.

Hunter, J. E., amp; Schmidt, F. L. (2004). Methods of meta- analysis: Correcting error and bias in research findings. Sage.

*Islam, G., amp; Zyphur, M. J. (2005). Power, voice, and hierarchy: Exploring the antecedents of speaking up in groups. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 9(2), 93−103.

*Issac, A. C., Bednall, T. C., Baral, R., Magliocca, P., amp; Dhir, A. (2023). The effects of expert power and referent power on knowledge sharing and knowledge hiding. Journal of Knowledge Management, 27(2), 383−403.

*Jain, A. K., Giga, S. I., amp; Cooper, C. L. (2011). Social power as a means of increasing personal and organizational effectiveness: The mediating role of organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Management amp; Organization, 17(3), 412−432.

*Jia, J., Ma, G., Li, H., Ding, J., amp; Liu, K. (2022). Social power antecedents of knowledge sharing in project- oriented online communities. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 71, 2493−2505.

*Jin, F., Zhu, H., amp; Tu, P. (2020). How recipient group membership affects the effect of power states on prosocial behaviors. Journal of Business Research, 108, 307-315.

*Jin, J., Li, Y., amp; Liu, S. (2021). Selfish power and unselfish status in chinese work situations. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 24(1), 98−110.

*Joosten, A., van Dijke, M., Van Hiel, A., amp; De Cremer, D. (2015). Out of control!? How loss of self-control influences prosocial behavior: The role of power and moral values. Plos One, 10(5), e0126377.

Joshi, A., amp; Roh, H. (2009). The role of context in work team diversity research: A meta-analytic review. Academy of Management Journal, 52(3), 599−627.

*Ju, D., Huang, M., Liu, D., Qin, X., Hu, Q., amp; Chen, C. (2019). Supervisory consequences of abusive supervision: An investigation of sense of power, managerial self-efficacy, and task-oriented leadership behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 154, 80−95.

*Kamans, E., Otten, S., Gordijn, E. H., amp; Spears, R. (2010). How groups contest depends on group power and the likelihood that power determines victory and defeat. Group Processes amp; Intergroup Relations, 13(6), 715−724.

Keltner, D., Gruenfeld, D. H., amp; Anderson, C. (2003). Power, approach, and inhibition. Psychological Review, 110(2), 265−284.

*Khahan, N.-N., Vrabcová, P., Prompong, T., amp; Nattapong, T. (2024). Moderating effects of resilience on the relationship between self-leadership and innovative work behavior. Sustainable Futures, 7, 100148.

*Kim, J., Shin, Y., amp; Lee, S. (2017). Built on stone or sand: The stable powerful are unethical, the unstable powerful are not. Journal of Business Ethics, 144, 437−447.

*Kim, K. H., amp; Guinote, A. (2022). Cheating to win or not to lose: Power and situational framing affect unethical behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 52(3), 137−144.

*Kim, T. H., Lee, S. S., Oh, J., amp; Lee, S. (2019). Too powerless to speak up: Effects of social rejection on sense of power and employee voice. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 49(10), 655−667.

Körner, R., amp; Schütz, A. (2024). Power balance and relationship quality: An overstated link. Social Psychological and Personality Science, https://doi.org/10.1177/19485506241234391

*Lammers, J., amp; Burgmer, P. (2019). Power increases the self-serving bias in the attribution of collective successes and failures. European Journal of Social Psychology, 49(5), 1087−1095.

*Lammers, J., Stapel, D. A., amp; Galinsky, A. D. (2010). Power increases hypocrisy: Moralizing in reasoning, immorality in behavior. Psychological Science, 21(5), 737−744.

*Lammers, J., Stoker, J. I., amp; Stapel, D. A. (2009). Differentiating social and personal power: Opposite effects on stereotyping, but parallel effects on behavioral approach tendencies. Psychological Science, 20(12), 1543−1548.

*Lammers, J., Stoker, J. I., amp; Stapel, D. A. (2010). Power and behavioral approach orientation in existing power relations and the mediating effect of income. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40(3), 543−551.

*Laslo-Roth, R., amp; Schmidt-Barad, T. (2020). Personal sense of power, emotion and compliance in the workplace: A moderated mediation approach. International Journal of Conflict Management, 32(1), 39−61.

*Lata, M., amp; Chaudhary, R. (2022). Workplace spirituality and employee incivility: Exploring the role of ethical climate and narcissism. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 102, 103178.

*Le, Q.-A., amp; Lee, C.-Y. (2023). Below-aspiration performance and risk-taking behaviour in the context of taiwanese electronic firms: A contingency analysis. Asia Pacific Business Review, 29(3), 654−677.

*Li, H., Chen, Y.-R., amp; Hildreth, J. A. D. (2022). Powerlessness also corrupts: Lower power increases self-promotional lying. Organization Science, 34(4), 1442−1440.

Liang, S., amp; Chang, Y. (2016). Social exclusion and choice: The moderating effect of power state. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 15(5), 449−458.

*Lin, X., Chen, Z. X., Tse, H. H. M., Wei, W., amp; Ma, C. (2019). Why and when employees like to speak up more under humble leaders? The roles of personal sense of power and power distance. Journal of Business Ethics, 158(4), 937−950.

*Liu, X., Wen, J., Zhang, L., amp; Chen, Y. (2021). Does organizational collectivist culture breed self-sacrificial leadership? Testing a moderated mediation model. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102862.

*Liu, Y., Chen, S., Bell, C., amp; Tan, J. (2020). How do power and status differ in predicting unethical decisions? A cross-national comparison of China and Canada. Journal of Business Ethics, 167, 745−760.

*Liu, Y., Wang, W., Lu, H., amp; Yuan, P. (2022). The divergent effects of employees’ sense of power on constructive and defensive voice behavior: A cross-level moderated mediation model. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 39(4), 1341−1366.

*Loi, R., Lin, X., amp; Tan, A. J. (2019). Powered to craft? The roles of flexibility and perceived organizational support. Journal of Business Research, 104, 61−68.

*Lu, J. G., Brockner, J., Vardi, Y., amp; Weitz, E. (2017). The dark side of experiencing job autonomy: Unethical behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 73, 222−234.

*Luo, S., Wang, J., Xie, Z., amp; Tong, D. (2023). When and why are employees willing to engage in voice behavior: A power cognition perspective. Current Psychology, 43(5), 4211−4222.

*Magni, F., Gong, Y., Li, J., Pan, J., amp; Zhou, M. (2022). The paradoxical relationship between sense of power and creativity: Countervailing pathways and a boundary condition. Personnel Psychology, 77(2), 441−474.

*Mayer, D. M., Thau, S., Workman, K. M., Van Dijke, M., amp; De Cremer, D. (2012). Leader mistreatment, employee hostility, and deviant behaviors: Integrating self- uncertainty and thwarted needs perspectives on deviance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 117(1), 24−40.

*Metin Camgoz, S., Bayhan Karapinar, P., Tayfur Ekmekci, O., Metin Orta, I., amp; Ozbilgin, M. F. (2023). Why do some followers remain silent in response to abusive supervision? A system justification perspective. European Management Journal, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2023.07.001

Min, D., amp; Kim, J. H. (2013). Is power powerful? Power, confidence, and goal pursuit. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 30(3), 265−275.

*Mooijman, M., Kouchaki, M., Beall, E., amp; Graham, J. (2020). Power decreases the moral condemnation of disgust-inducing transgressions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 161, 79−92.

*Mooijman, M., van Dijk, W. W., van Dijk, E., amp; Ellemers, N. (2019). Leader power, power stability, and interpersonal trust. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 152, 1−10.

*Morrison, E. W., See, K. E., amp; Pan, C. (2015). An approach-inhibition model of employee silence: The joint effects of personal sense of power and target openness. Personnel Psychology, 68(3), 547−580.

Nikitin, J., amp; Freund, A. M. (2010). When wanting and fearing go together: The effect of co-occurring social approach and avoidance motivation on behavior, affect, and cognition. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40(5), 783−804.

*Overall, N., Maner, J., Hammond, M., Cross, E., Chang, V., Low, R., . . . Sasaki, E. (2022). Actor and partner power are distinct and have differential effects on social behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 124(2), 311−343.

*Pai, J., Whitson, J., Kim, J., amp; Lee, S. (2021). A relational account of low power: The role of the attachment system in reduced proactivity. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 167, 28−41.

*Park, I.-J., Doan, T., Zhu, D., amp; Kim, P. B. (2021). How do empowered employees engage in voice behaviors? A moderated mediation model based on work-related flow and supervisors’ emotional expression spin. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 95, 102878.

Podsakoff, N. P., LePine, J. A., amp; LePine, M. A. (2007). Differential challenge stressor-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 438−454.

Puleo, B. K. (2020). Laboratory-derived, coded communicative behaviors among individuals with cancer and their caregiving partners [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Arizona State University.

*Qiuyun, G., Liu, W., Zhou, K., amp; Mao, J. (2020). Leader humility and employee organizational deviance: The role of sense of power and organizational identification. Leadership amp; Organization Development Journal, 41(3), 463−479.

*Randolph, W. A., amp; Kemery, E. R. (2011). Managerial use of power bases in a model of managerial empowerment practices and employee psychological empowerment. Journal of Leadership amp; Organizational Studies, 18(1), 95−106.

*Rios, K., Fast, N. J., amp; Gruenfeld, D. H. (2015). Feeling high but playing low:Power, need to belong, and submissive behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(8), 1135−1146.

*Rong, Y., Yang, B., amp; Ma, L. (2017). Leaders' sense of power and team performance: A moderated mediation model. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 45(4), 641−656.

*Rus, D., Van Knippenberg, D., amp; Wisse, B. (2010). Leader power and leader self-serving behavior: The role of effective leadership beliefs and performance information. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(6), 922−933.

*Rus, D., van Knippenberg, D., amp; Wisse, B. (2012). Leader power and self-serving behavior: The moderating role of accountability. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(1), 13−26.

*Sahadev, S. (2005). Exploring the role of expert power in channel management: An empirical study. Industrial Marketing Management, 34(5), 487−494.

*Sanders, S., Wisse, B. M., amp; Van Yperen, N. W. (2015). Holding others in contempt: The moderating role of power in the relationship between leaders’ contempt and their behavior vis-à-vis employees. Business Ethics Quarterly, 25(2), 213−241.

Schaerer, M., Swaab, R. I., amp; Galinsky, A. D. (2015). Anchors weigh more than power: Why absolute powerlessness liberates negotiators to achieve better outcomes. Psychological Science, 25, 1581−1591.

*Schaerer, M., Tost, L. P., Huang, L., Gino, F., amp; Larrick, R. (2018). Advice giving: A subtle pathway to power. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(5), 746−761.

Schmidt, F. L., Oh, I. S., amp; Hayes, T. L. (2009). Fixed-versus random-effects models in meta-analysis: Model properties and an empirical comparison of differences in results. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 62(1), 97−128.

*Sekścińska, K., Rudzinska-Wojciechowska, J., amp; Kusev, P. (2022). How decision-makers’ sense and state of power induce propensity to take financial risks. Journal of Economic Psychology, 89, 102474.

*Seppälä, T., Lipponen, J., Bardi, A., amp; Pirttilä-Backman, A. M. (2012). Change-oriented organizational citizenship behaviour: An interactive product of openness to change values, work unit identification, and sense of power. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 85(1), 136−155.

*Sijbom, R. B., amp; Parker, S. K. (2020). When are leaders receptive to voiced creative ideas? Joint effects of leaders’ achievement goals and personal sense of power. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 497790.

*Slabu, L., amp; Guinote, A. (2010). Getting what you want: Power increases the accessibility of active goals. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(2), 344−349.

*Smith, P. K., amp; Bargh, J. A. (2008). Nonconscious effects of power on basic approach and avoidance tendencies. Social Cognition, 26(1), 1−24.

Smith, P. K., amp; Galinsky, A. D. (2010). The nonconscious nature of power: Cues and consequences. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(10), 918−938.

*Smith, P. K., Jost, J. T., amp; Vijay, R. (2008). Legitimacy crisis? Behavioral approach and inhibition when power differences are left unexplained. Social Justice Research, 21, 358−376.

Smith, P. K., amp; Trope, Y. (2006). You focus on the forest when you're in charge of the trees: Power priming and abstract information processing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(4), 578−596.

*Sun, P., Li, H., Liu, Z., Ren, M., Guo, Q., amp; Kou, Y. (2021). When and why does sense of power hinder self-reported helping behavior? Testing a moderated mediation model in chinese undergraduates. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 51(5), 502−512.

Taras, V., Steel, P., amp; Kirkman, B. L. (2012). Improving national cultural indices using a longitudinal meta- analysis of Hofstede's dimensions. Journal of World Business, 47(3), 329−341.

Ten Brinke, L., amp; Keltner, D. (2022). Theories of power: Perceived strategies for gaining and maintaining power. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 122(1), 53−72.

Tonidandel, S., amp; LeBreton, J. M. (2015). Rwa web: A free, comprehensive, web-based, and user-friendly tool for relative weight analyses. Journal of Business and Psychology, 30(2), 207−216.

*Tost, L. P., Gino, F., amp; Larrick, R. P. (2012). Power, competitiveness, and advice taking: Why the powerful don’t listen. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 117(1), 53−65.

*Tost, L. P., Gino, F., amp; Larrick, R. P. (2013). When power makes others speechless: The negative impact of leader power on team performance. Academy of Management Journal, 56(5), 1465−1486.

*Tost, L. P., amp; Johnson, H. H. (2019). The prosocial side of power: How structural power over subordinates can promote social responsibility. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 152, 25−46.

*Van Dijke, M., De Cremer, D., Langendijk, G., amp; Anderson, C. (2018). Ranking low, feeling high: How hierarchical position and experienced power promote prosocial behavior in response to procedural justice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(2), 164−219.

Van Kleef, G. A., amp; Lange, J. (2020). How hierarchy shapes our emotional lives: Effects of power and status on emotional experience, expression, and responsiveness. Current Opinion in Psychology, 33, 148−153.

*Villa, S., amp; Castañeda, J. A. (2020). A behavioural investigation of power and gender heterogeneity in operations management under uncertainty. Management Research Review, 43(6), 753−771.

Viswesvaran, C., amp; Ones, D. S. (1995). Theory testing: Combining psychometric meta‐analysis and structural equations modeling. Personnel Psychology, 48(4), 865−885.

*Vriend, T., Jordan, J., amp; Janssen, O. (2016). Reaching the top and avoiding the bottom: How ranking motivates unethical intentions and behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 137, 142−155.

Wagers, S. M. (2015). Deconstructing the “power and control motive”: Moving beyond a unidimensional view of power in domestic violence theory. Partner Abuse, 6(2), 230−242.

Wagers, S. M., Wareham, J., amp; Sellers, C. S. (2021). Testing the validity of an internal power theory of interpersonal violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(15-16), 7223−7248.

*Wang, P., Zou, L., Huang, M., Amdu, M. K., amp; Guo, T. (2024). Work-related identity discrepancy and employee proactive behavior: The effects of face-pressure and benevolent leadership. Acta Psychologica, 248, 104354.

*Wang, Y. (2020). When power increases perspective-taking: The moderating role of syncretic self-esteem. Personality and Individual Differences, 166, 110207.

*Webster, B. D., Greenbaum, R. L., Mawritz, M. B., amp; Reid, R. J. (2022). Powerful, high-performing employees and psychological entitlement: The detrimental effects on citizenship behaviors. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 136, 103725.

Wei, X. (2024). Smart meta-analysis (SMA) user manual (pp. 1−8). Lanzhou: Lanzhou University. doi: 10.13140/ RG.2.2.16133.56803

Wiltermuth, S. S., amp; Flynn, F. J. (2013). Power, moral clarity, and punishment in the workplace. Academy of Management Journal, 56(4), 1002−1023.

*Wisse, B., amp; Rus, D. (2012). Leader self-concept and self-interested behavior. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 11(1), 40−48.

*Yoon, D. J., amp; Farmer, S. M. (2018). Power that builds others and power that breaks: Effects of power and humility on altruism and incivility in female employees. The Journal of Psychology, 152(1), 1−24.

Yu, A., Hays, N. A., amp; Zhao, E. Y. (2019). Development of a bipartite measure of social hierarchy: The perceived power and perceived status scales. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 152, 84−104.

*Yu, A., Xu, W., amp; Pichler, S. (2022). A social hierarchy perspective on the relationship between leader–member exchange (LMX) and interpersonal citizenship. Journal of Management amp; Organization, https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2022.87

*Yu, F., Wu, Y., amp; Liu, J. (2018). Narcissistic leadership and feedback avoidance behavior: The role of sense of power and proactive personality. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Business and Information Management.

*Yuan, P., Ju, F., Cheng, Y., amp; Liu, Y. (2021). Influence of sense of power on epidemic control policy compliance. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 49(9), 1−12.

Yukl, G., amp; Falbe, C. M. (1991). Importance of different power sources in downward and lateral relations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(3), 416−423.

*Zhang, Z., Gong, M., Jia, M., amp; Zhu, Q. (2024). Why and when does CFO ranking in top management team informal hierarchy affect entrepreneurial firm initial public offering fraud? Journal of Management Studies,61(7), 2775−3400.

*Zhong, Y., amp; Li, H. (2024). Do lower-power individuals really compete less? An investigation of covert competition. Organization Science, 35(2), 741−768.

*Zhou, H., amp; He, H. (2020). Exploring role of personal sense of power in facilitation of employee creativity: A dual mediation model based on the derivative view of self-determination theory. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 13, 517−527.

The behavioral theory of approach-inhibition of power:Theoretical expansion based on a meta-analysis

WEI Xuhua, JIAO Wenying

(School of Management, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, China)

Abstract: The power approach-inhibition theory is an important theory for explaining the power-behavior relationship, but empirical studies applying the theory have findings that contradict the theory. By integrating a meta-analysis of 154 literatures and 261 effect sizes from 245 empirical samples exploring the relationship between power and approach and inhibition behavior from 2003~2023, this study examined the mechanism of the double-edged sword effect of the power and approach-inhibition behavior relationship and the boundary conditions, with a view to explaining the inconsistencies in the conclusions of previous studies. The results showed that the power and approach-inhibition behavior relationship had a double-edged sword effect, with objective power indirectly increasing approach and decreasing inhibition through subjective power, as well as directly contributing to inhibition, and with subjective power having a stronger explanatory power for behavior than objective power. The moderating effect results showed that power distance strengthened the positive effect of subjective power on approach behavior and the negative effect of subjective power on inhibition behavior. The above findings help to deepen and expand the theoretical framework of power approach-inhibition behavior.

Keywords: power, approach-inhibition theory of power, meta-analysis, approach behavior, inhibition behavior

* 国家自然科学基金项目(71972093, 72372063); 甘肃省哲学社会科学规划项目(2023YB013); 兰州大学中央高校基本科研业务费专项资金项目(2023jbkyzx005)。

通信作者:焦文颖, E-mail: 542578717@qq.com.cn