歌剧与我:拉玛五世的歌剧之旅

2025-01-31司马勤

在泰国(旧称为“暹罗”)境外,朱拉隆功国王(1853—1910)最广为人知的形象可能是百老汇音乐剧《国王与我》(The King and I)中的年轻王储,他是在外国教师指导下接触西方生活方式的暹罗王室成员之一。那位著名的老师——她非常能歌善舞——就是来自英国的安娜·李奥诺文斯夫人(Anna Leonowens)。理察·罗杰斯和奥斯卡·汉默斯坦二世在创作音乐剧时,基于史实做了一些自由的处理——就像李奥诺文斯本人在她的回忆录中所写的那样——但实际上,朱拉隆功在课堂上确实很用功。即使在他以暹罗拉玛五世(当时该国的官方名称)的身份登上王位后,并将所学西方知识付诸实践时,他仍然是一名专注的学生。

事实上,拉玛五世最后的课堂之一就是歌剧院。在1907年朱拉隆功第二次欧洲之行期间,他花了很多时间来观察西方科学(通常是医学)的进步。不过,晚上的行程通常是在当地政要的陪同下,围绕着歌剧展开。朱拉隆功的日记和信件——主要是写给他的女儿乌通公主(Princess Nibha Nobhadol)的——字里行间里充满了对歌剧这种艺术形式的长篇大论。

虽然朱拉隆功从未对西方美声唱法的真实发声方法产生过兴趣,但他对其艺术表达的宽度感到惊讶。“在这种音量下,我们国家歌手的歌声听起来就像是喃喃自语,完全会被乐器的声音淹没。”他在给同父异母的弟弟纳拉提巴攀蓬王子(Prince Narathip Praphanphong)的信中写道。纳拉提巴攀蓬王子是当时暹罗王室中的宫廷音乐负责人。但当一位意大利教授邀请两名暹罗学生到欧洲学习歌剧时,朱拉隆功怀疑这种学习的必要性。 “在曼谷,只有少数人有品位去欣赏来自欧洲的声音”,他写道,“如果我们的学生去意大利接受训练,当他们回来时,我担心他们除了像狗一样嚎叫外,什么也做不了。”这与其说是朱拉隆功对学生声乐学习能力的贬低,不如说他认识到暹罗当地缺乏欣赏他们的观众。

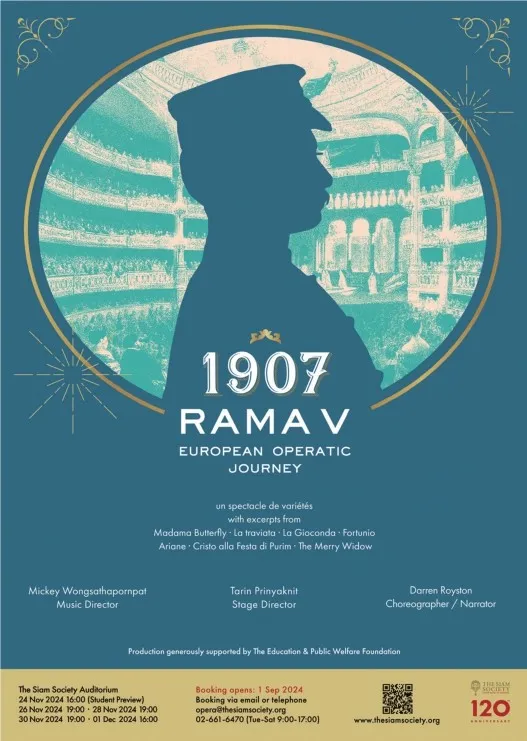

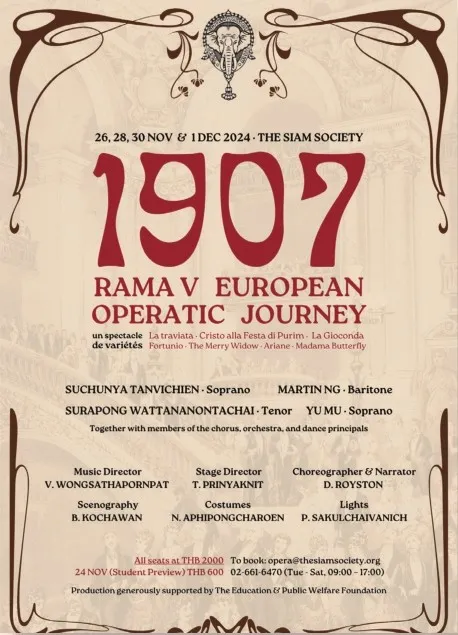

在暹罗协会(Siam Society)成立120周年之际,协会方构思了《1907:拉玛五世欧洲歌剧之旅》(1907: Rama V European Opera Journey),这是一部讲述并在一定程度上再现了拉玛五世在欧洲游历的舞台制作。该剧于2024年11月下旬在暹罗协会礼堂上演,五晚演出的门票全部售罄。作品中有史实故事的演绎,还有部分歌剧选段的上演,按时间顺序跟随拉玛五世的旅途,故事从都灵维托里奥·埃马努埃莱剧院开始。

朱拉隆功对西方歌剧剧目的最大赞赏在于其情节涵盖了古代神话故事和现代道德题材。当时的暹罗也有相类似的戏剧表演,但背景和故事的范围很难达到拉玛五世观赏的题材那样广泛。拉玛五世在都灵第一个晚上就观赏了讲述巴黎妓女爱情的故事,即威尔第的《茶花女》(La Traviata)。而他第二天看的乔万尼· 贾尼提的《普林节》(Cristo alla Festa di Purim)则是一个根据圣经故事改编的作品,讲述了耶稣从公开私刑中拯救一名妇女的故事。

对于《1907:拉玛五世欧洲歌剧之旅》的泰国制作团队来说,这项工作有时相对容易。朱拉隆功在信中没有提到具体的剧名,但他对巴黎社交沙龙、穿着现代服装的演员以及被情人的父亲敦促忘记他的儿子的描述,清晰地指向了《茶花女》这部作品。另一方面,指名道姓地引用乔万尼· 贾尼提的独幕剧帮助不大,因为这部歌剧如今鲜少听闻。但制作团队在罗马圣西西里亚国家学院历史资料馆(Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia)的档案中找到了《普林节》的钢琴谱。由《1907:拉玛五世欧洲歌剧之旅》音乐总监黄国能(Voraprach Wongsathapornpat)精心配器的终曲管弦乐版是演出当晚的高潮。

在舞台上,导演塔林·普林雅克尼特(Tarin Prinyaknit)巧妙地利用了一个临时搭建的T形舞台,而台上覆盖着巴米·科查万(Bamee Kochawan)设计的演出场刊和报纸报道的拼贴画,40人编制的暹罗小交响乐团放在一侧的固定舞台上。舞蹈编导达伦·罗伊斯顿(Darren Royston)也担任了该剧的串场主持,帮助T台两侧的观众了解故事的历史背景,并引用拉玛五世在信中对每部具体歌剧的评论。随后的表演在很大程度上反映了这些描述,由四名年轻的亚洲歌手以及当地舞者和合唱团轮流担纲演出。男高音苏拉蓬·瓦塔纳诺塔奇(Surapong Wattananontachai)在《茶花女》的祝酒歌段落中带领了一个训练有素的16人合唱团;6位舞者熟练地演绎了蓬基耶利的《歌女乔康达》(La Gioconda)和马斯内的《阿丽亚娜》(Ariane)中的芭蕾舞场景。

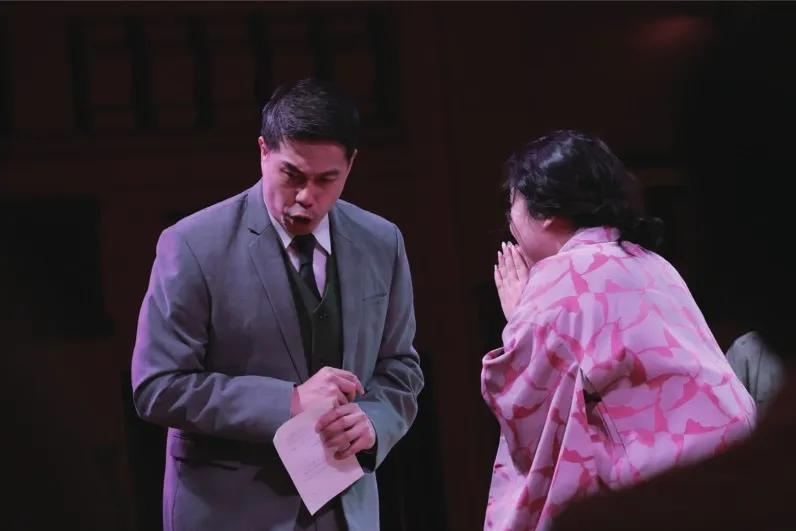

独唱家们的演出总是那么的引人入胜,而且常常能戏剧性地应付自如。中国女高音穆宇和新加坡男中音吴翰卫(Martin Ng)演唱了《风流寡妇》(The Merry Widow)中的二重唱“默默倾听”(Lippen schwenge)的英语演出版本I Love You So,以反映拉玛五世在伦敦戴利剧院的观剧经历,魅力四射。吴翰卫和女高音苏春雅·坦维琴(Suchunya Tanvichien)演唱的二重唱“瓦莱丽小姐”(Madamigella Valéry),强度令人信服,就像他们刚刚走出了正在进行中的《茶花女》。

在提炼自《蝴蝶夫人》多个选段中,概念和结果最有效地结合在一起。这部作品(包括角色)是给拉玛五世留下最深刻印象的歌剧之一。朱拉隆功欣赏了巴黎喜歌剧院的演出——在斯卡拉歌剧院首演失败后,普契尼正是在这里亲自操刀,让这部作品起死回生。在新的巴黎制作中,导演阿尔伯特·卡雷(Albert Carré)不仅展示了西方戏剧的最新进步(如当时的现代舞台灯光),还展现了日本传统文化的尊严。拉玛五世给女儿的信中不仅包含了详细的剧情概要,还包括了他对这部作品人物和舞台的感想(注:这个制作最初于1906年推出,在喜歌剧院一直上演至1972年)。

《1907》的最后一段基本上成了穆宇的展示舞台,她表演了一系列歌剧中精彩片段,从巧巧桑的咏叹调“晴朗的一天”(Un bel di)到二重唱“现在轮到我们谈谈”(Ora a noi),再到最后的“你,你,永别我的宝贝”(Tu, tu piccolo iddio),当然离不开苏拉蓬·瓦塔纳诺塔奇饰演的平克尔顿和吴翰卫饰演的夏普莱斯的支持。总之,这些音乐速写为蝴蝶夫人的情感弧线提供了高效而有益的写照。

看完演出后的几天里,我有两个挥之不去的印象。其中一个是黄国能侧身站在指挥台上的视觉强度,他一只手天衣无缝地指挥着乐队,另一只手引导着舞台表演。这并不是最佳的指挥位置,但可能与现代管弦乐队的乐池及监视器屏幕(舞台上的表演者可以从不同的有利位置看到并跟随指挥)出现之前的许多现场演奏的作品相似。

然而,演出当晚的效果要微妙得多。听到两代截然不同的亚洲人提出他们对西方歌剧的看法,很难反驳当年朱拉隆功国王对经典歌剧剧目是否能吸引亚洲观众的质疑。只是,就像在许多其他领域一样,这场演出证明这位暹罗国王比他的时代领先了一个世纪左右。

Outside of Thailand, King Chulalongkorn (1853–1910) is probably best known as a young boy in the Broadway musical The King and I, one of the royal brood exposed to Western ways through foreign tutors, most famously—and tunefully—Anna Leonowens. Rodgers and Hammerstein took a few factual liberties—as did Leonowens herself in her memoirs—but the actual Chulalongkorn did actually pay attention in class. Even after assuming the throne himself as Rama V of Siam (as the country was then officially known), when he started putting that knowledge into practice, he still remained an avid student.

One of the King’s final classrooms, in fact, was the opera house. During his second European tour in 1907, Chulalongkorn spent his days observing Western scientific (usually medical) advances. Evenings, though, revolved around the opera, which he usually attended in the company of local dignitaries. Chulalongkorn’s diaries and letters—written mostly to his daughter, Princess Nibha Nobhadol—brim with lengthy reactions to the art form.

Though he never quite warmed to the actual sound of cultivated Western singing, he marveled at its expressive range. “Against this volume, our singing sounds like mumbling, and would entirely be drowned out by the instruments,” he wrote to his half-brother Prince Narathip Praphanphong, who was in charge of music in the royal court. But when an Italian professor asked for two local students to come Europe to study opera, Chulalongkorn doubted it was possible. “In Bangkok, only a handful of individuals have the taste to appreciate the European sound,” he wrote. “If our students go to Italy for training, when they return, I am afraid that they would not be able to do much except howl like dogs.” It was less a disparagement of the students’ vocal abilities than recognizing the lack of a local audience to appreciate them.

As part of its 120th anniversary celebration, the Siam Society conceived and developed 1907: Rama V European Opera Journey, a staged production recounting—and in part recreating—those experiences, which played in a sold-out, five-night run in the Siam Society Auditorium in late November. Part pastiche, part operatic variety show, the show followed the King’s travels chronologically, beginning at Turin’s Teatro Vittorio Emanuele.

Chulalongkorn’s greatest admiration for Western repertory lay in its breadth of subject matter, spanning both ancient myth and modern morals. Thai theatrical performances did much the same thing, but the settings and stories hardly ranged as broadly as Verdi’s La Traviata with its Parisian courtesan, which the King saw on his first night at the opera in Turin, to Giovanni Giannetti’s Cristo alla Festa di Purim, based on the biblical tale of Jesus saving a woman from public lynching, which he saw the next evening.

For the Thai production team of 1907, the job was sometimes easy. Chulalongkorn may have neglected to mention the title of Traviata, but his descriptions of Paris salons, actors in modern dress and the lead female character being urged by her potential father-inlaw to forget his son clearly pointed in that direction. On the other hand, citing Giannetti’s one-act by name helped very little, as the opera barely warrants a footnote today. The team went in search of the music, finding a vocal score in the archives at Rome’s Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia. Giannetti’s finale, orchestrated by the production’s music director Voraprach Wongsathapornpat, turned out to be a high point of the evening.

In the staging itself, director Tarin Prinyaknit made fine use of a catwalk stage draped in scenic designer Bamee Kochawan’s collage of historic concert programs and newspaper reports with the 40-piece Siam Sinfonietta placed on a raised stage at one side. Choreographer Darren Royston also served as the show’s host, engaging audiences on both sides of the catwalk with historical context and quotes from the King’s observations of each particular opera. Musical performances were then staged largely to reflect those descriptions, the performance distributed equitably among a quartet of young Asian singers along with teams of local dancers and choristers. Tenor Surapong Wattananontachai led a well-drilled vocal ensemble in champagne toasts from Traviata; dancers deftly rendered ballet scenes from Ponchielli’s La Gioconda and Massenet’s Ariane.

The soloists were never less than engaging, and often rose to the occasion dramatically. Chinese Soprano Mu Yu and Singaporean baritone Martin Ng offered the duet “Lippen schweigen” from The Merry Widow (rendered in English as “I Love You So” to reflect the King’s attendance at Daly’s Theatre in London) with more charm than stylistic flair, though Ng and soprano Suchunya Tanvichien sang the “Madamigella Valéry” duet with enough intensity to suggest they’d just stepped out of a Traviata already in progress.

Concept and outcome came together most effectively in a lengthy distillation from Madama Butterfly, the show (and character) among the King’s operatic experiences that left the deepest impression. Chulalongkorn had attended the production at Paris’s Opéra-Comique, where Puccini himself had resurrected the show after its failed premiere at La Scala. In its new incarnation, director Albert Carré brought out not just the most recent Western theatrical advancements (such as then-modern stage lighting) but also the dignity of traditional Japanese culture. The King’s letters to his daughter contained not only a detailed synopsis of the plot but also his own reactions to the characters and the staging. (Note: This staging, originally introduced in 1906, was used at Opéra-Comique until 1972.)

The final segment of 1907 essentially became a showcase for Mu, who performed a series of the opera’s highlights, from the aria “Un bel di” to the duet“Ora a noi” to her final “Tu, tu piccolo iddio” (with support from Wattananontachai’s Pinkerton and Ng’s Sharpless). Taken together, these musical snapshots provided an efficient and rewarding portrayal of Butterfly’s emotional arc.

Leaving the performance—and for several days after—I had two lasting impressions. The first was the visual intensity of Wongsathapornpat standing on the podium sideways, seamlessly leading the orchestra with one hand and the stage proceedings with the other. This was hardly optimal positioning, but probably not unlike many productions in the days before modern orchestra pits, or monitor screens where performers on stage could follow the conductor from different vantage points.

The evening’s emotional impact, however, was rather more subtle. Hearing two very different Asian generations offer their take on Western opera hardly refutated King Chulalongkorn’s doubts that the repertory would ever find an Asian audience. It was just that, as in many other fields, the King was a century or so ahead of his time.