上海某三甲医院利奈唑胺非敏感肠球菌的流行趋势、分布特征与耐药性分析

2024-12-31张艳君 万玉香 马炜 黄晓春 徐丽 邓嫦姿 林佳 秦琴

摘要:目的 了解上海某三甲医院利奈唑胺非敏感肠球菌的流行趋势、分布特征及其耐药性,为指导临床合理用药和抗感染治疗提供依据。方法 采用自动化仪器方法、纸片扩散法(K-B法)和E-test方法对2018年1月—2022年12月分离的菌株进行药物敏感性试验,参照2022版CLSI M100-S32标准判断药敏结果。结果 共分离出非重复利奈唑胺非敏感肠球菌(linezolid non-sensitive Enterococcus, LNSE)142株,其中粪肠球菌128株(90.1%),屎肠球菌13株(9.2%),鸟肠球菌1株(0.7%)。5年非敏感粪肠球菌(linezolid non-sensitive E. faecalis,LNSEFA)平均检出比例(128/1621, 7.9%)高于非敏感屎肠球菌(linezolid non-sensitive E. faecium,LNSEFM)(13/1075, 1.2%),2019—2022年LNSE检出率明显高于2018年。分离菌株数位于前三位的标本类型是尿(50.4%),分泌物(20.6%),引流液(17.7%),分离菌株数位于前五位的科室是门诊(22.0%)、泌尿外科(19.2%)、重症医学科(10.6%)、肛肠外科(9.9%)、烧伤科(9.2%)。药敏结果显示LNSEFA对抗生素的耐药率多数高于利奈唑胺敏感粪肠球菌(linezolid sensitive E. faecalis, LSEFA),但对青霉素和呋喃妥因的耐药率低于LSEFA,LNSEFA和LSEFA二者对磷霉素、青霉素G、呋喃妥因、氨苄西林敏感率较高,对万古霉素非敏感率为0。LNSEFM对四环素、高浓度链霉素的耐药率高于利奈唑胺敏感屎肠球菌(linezolid sensitive E. faecium, LSEFM),对青霉素、氨苄西林、呋喃妥因和万古霉素耐药率低于LSEFM。LNSEFM对万古霉素耐药率为0,而LSEFM对万古霉素耐药率为0.6%。结论 LNSE近几年呈上升趋势,对多数抗生素耐药形势严峻,应加强对其监测,指导抗生素的合理使用,预防和控制此类耐药菌在院内传播。

关键词:利奈唑胺;肠球菌;耐药性;流行趋势

中图分类号:R978.1 文献标志码:A

Epidemiology, distribution characteristics and drug resistance analysis of linezolid non-sensitive Enterococcus in a tertiary hospital in Shanghai

Zhang Yanjun1, Wan Yuxiang2, Ma Wei2," Huang Xiaochun2, Xu Li2, Deng Changzi2, Lin Jia2, and Qin Qin2

(1 Department of Disease Control and Prevention, the First Affiliated Hospital of Second Military Medical University, Shanghai 200433;" 2 Department of Clinical Laboratory Diagnosis, the First Affiliated Hospital of Second Military Medical University, Shanghai 200433)

Abstract Objective This study investigated the epidemiology, distribution and antimicrobial resistance of linezolid non-sensitive Enterococcus in a tertiary hospital in Shanghai during 2018—2022, for the rational use of antibacterial agents. Methods From January 2018 to December 2022, the clinical linezolid non-sensitive Enterococcus (LNSE) was collected and subjected to antimicrobial susceptibility testing by using an automated instrument, the Kirby-Bauer method or E-test testing. The results were interpreted according to CLSI M100-S32 standard. Results A total of 142 non-duplicate isolates of LNSE were collected, of which E. faecalis (128 isolates), E. faecium (13 isolates) and E. avium (1 isolate) accounted for 90.1%, 9.2% and 0.7%, respectively. The average detection rate of linezolid non-sensitive E. faecalis (LNSEFA) (128/1621, 7.9%) was higher than linezolid non-sensitive E. faecium (LNSEFM) (13/1075, 1.2%). The detection rate of LNSE from 2019 to 2022 was obviously higher than that of 2018. The specimens with the highest number of isolated LNSE were urine (50.4%), secretion (20.6%), and drainage fluid (17.7%). The departments of outpatient (22.0%), urology (19.2%), intensive care unit (10.6%), anorectal surgery (9.9%), and burn (9.2%) were the top 5 departments according to their total number of bacterial isolates. The results of antimicrobial susceptibility testing showed that LNSEFA strains showed higher resistance rates to most antibacterial agents than the linezolid sensitive E. faecalis (LSEFA) strains, while having lower resistance rates to penicillin G and nitrofurantoin than LSEFA strains. Both LNSEFA and LSEFA strains showed high sensitivity to fosfomycin, penicillin G, nitrofurantoin, and ampicillin, and the non-sensitive rate to vancomycin was 0. LNSEFM strains showed higher resistance rates to tetracycline, high concentrations of streptomycin than the linezolid sensitive E. faecium (LSEFM) strains, while having lower resistance rates to penicillin G, ampicillin, nitrofurantoin, and vancomycin than LSEFM strains. The resistance rate of LNSEFM to vancomycin was 0, while the resistance rate of LSEFM to vancomycin was 0.6%. Conclusion LNSE has been on the rise in recent years and is resistant to most antibiotics. It is necessary to strengthen the surveillance of LNSE for rational use of antibiotics and to prevent and control the spread of such resistant bacteria in hospitals.

Key words Linezolid; Enterococcus; Antimicrobial resistance; Epidemiology

肠球菌是临床上重要的条件致病菌,在革兰阳性菌检出中仅次于葡萄球菌,可引起尿路、腹腔、胆管胆囊、血流、颅内和牙齿根管等多个部位感染[1]。利奈唑胺是唑烷酮类抗菌药物,对大部分革兰阳性菌具有较强的抗菌作用,尤其是对万古霉素耐药肠球菌(vancomycin-resistant enterococci,VRE)和葡萄球菌[2]。但目前随着利奈唑胺的应用,利奈唑胺非敏感肠球菌(耐药和中介)(linezolid non-sensitive Enterococcus, LNSE)的比例有所上升,对不同抗生素的耐药率有所改变[3-5],对利奈唑胺耐药性的增加同时导致了VRE治疗失败,对临床治疗带来一定的挑战。为了更好地指导临床用药,为抗感染治疗提供依据,本研究对LNSE的流行趋势、分布特征及其耐药性进行总结分析。

1 材料和方法

1.1 菌株来源

所有菌株源自本院2018年1月—2022年12月患者标本培养检出。

1.2 试剂与仪器

采用德国Bruker公司微生物质谱仪器对菌株进行鉴定,采用法国梅里埃细菌鉴定药敏仪VITEK2-Compact、英国Oxoid纸片、温州康泰E-test条对细菌进行药敏试验,参照美国临床和实验室标准化协会(CLSI)2022年M100文件[6]判读药敏结果。质控菌株为金黄色葡萄球菌ATCC25923、金黄色葡萄球菌ATCC29213、粪肠球菌ATCC29212。

1.3 数据分析

采用Excel和WHONET软件分析数据。

2 结果

2.1 非敏感肠球菌在不同年份的检出

2018—2022年共检出非重复LNSE142株,其中粪肠球菌128株,占比为90.1%,屎肠球菌13株,占比为9.2%,鸟肠球菌1株,占比为0.7%(因鸟肠球菌检出数量少,以下不做分析)。2019—2022年检出比例(4.3%~8.6%)较2018年(0.8%)有明显提高。2018—2022年非敏感粪肠球菌(linezolid non-sensitive E. faecalis,LNSEFA)检出率介于1.0%~13.1%,均高于同年非敏感屎肠球菌(linezolid non-sensitive E. faecium, LNSEFM)检出率0.5%~1.7%。5年内LNSEFA平均检出率比例为7.9%(128/1621),高于LNSEFM平均检出比例1.2%(13/1075),见表1。

2.2 非敏感肠球菌在不同标本的检出

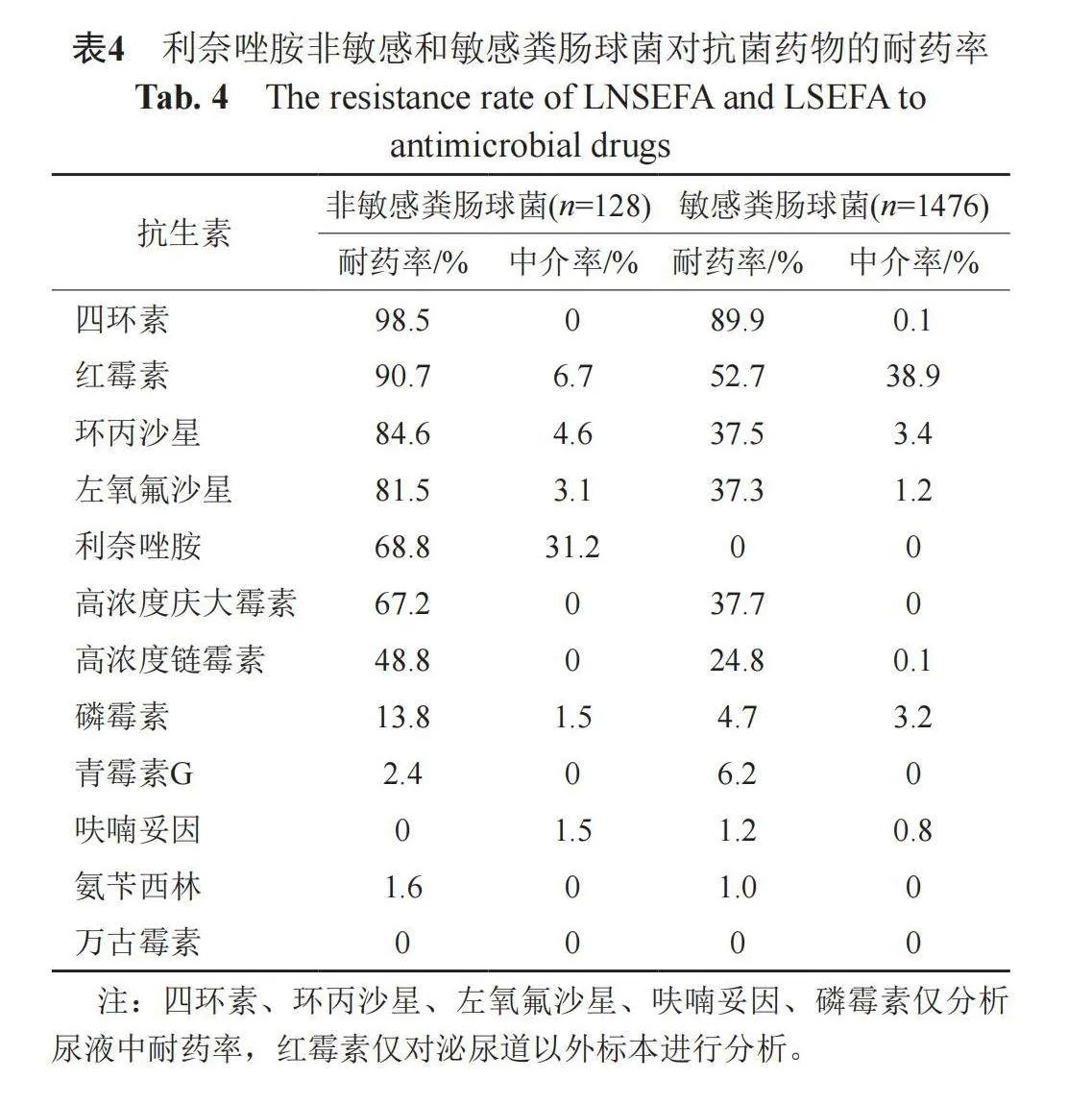

141株LNSE主要分布在尿、分泌物和引流液中,检出率分别为50.4%(71/141)、20.6%(29/141)和17.7%(25/141)。另在组织、腹水、血、脓液和胆汁中也有少量检出,见表2。

2.3 非敏感肠球菌在不同科室的检出

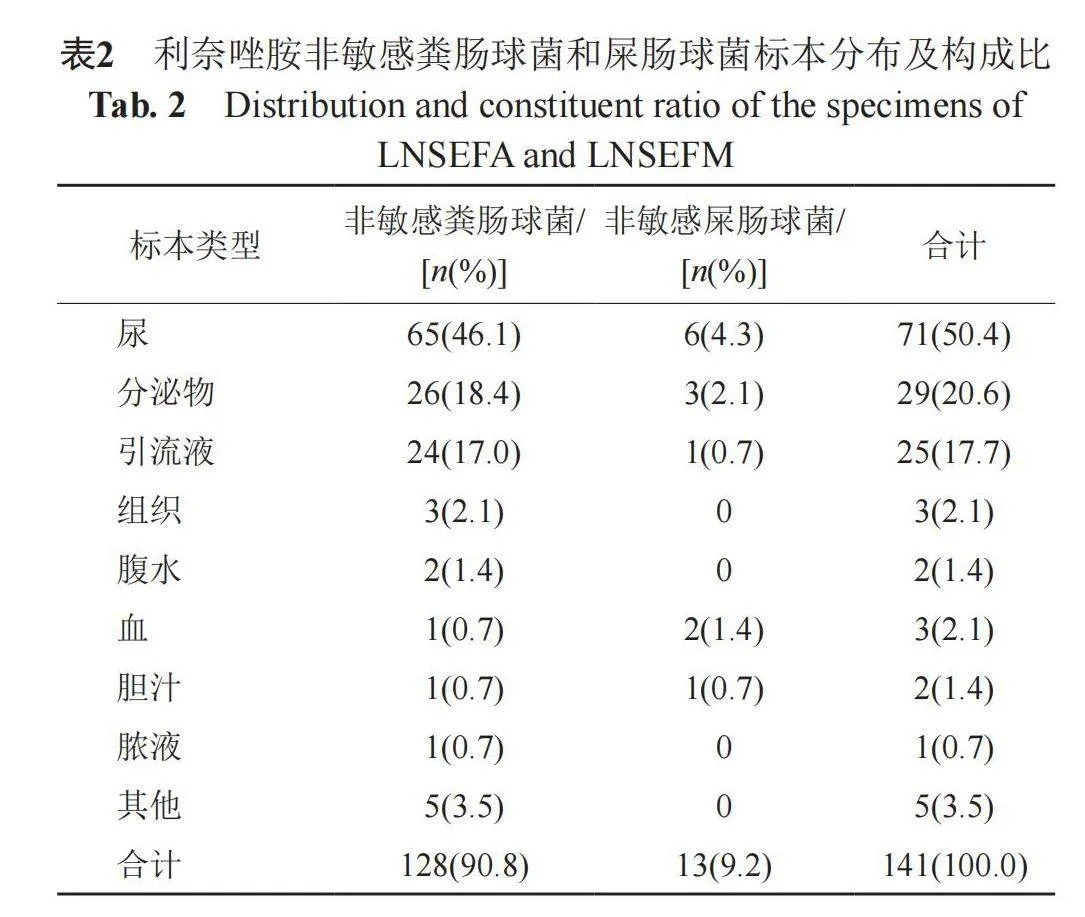

141株LNSEFA和LNSEFM检出数量最多的科室为门诊(31株,22.0%),其次为泌尿外科(19.2%)、重症医学科(10.6%)、肛肠外科和烧伤科(9.9%),见表3。

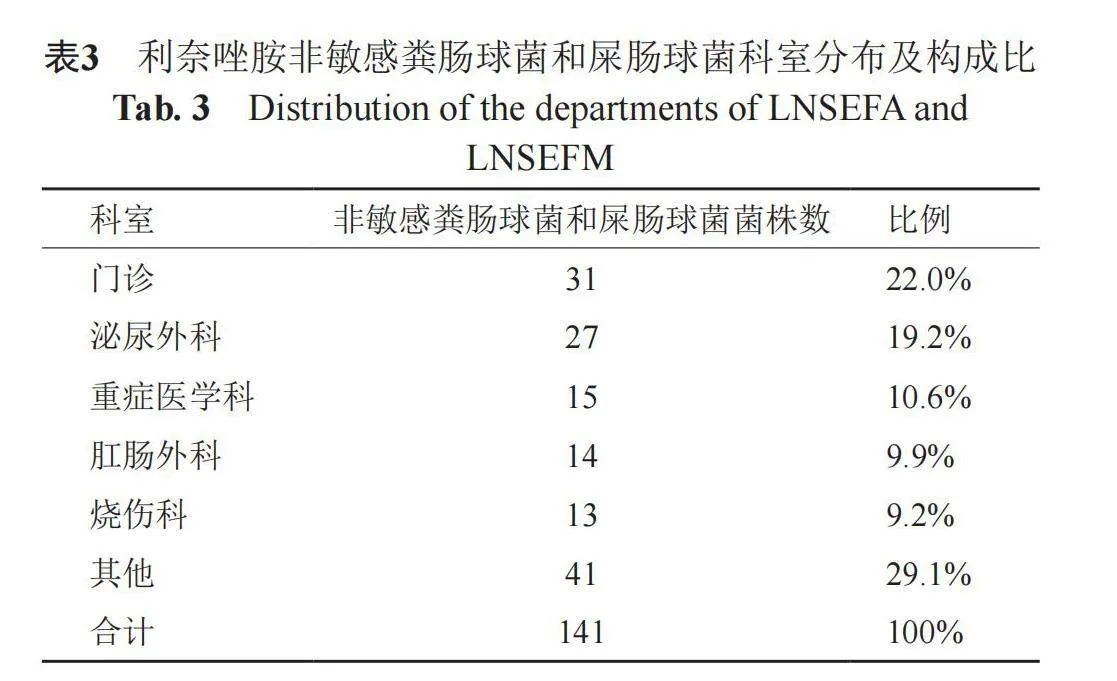

2.4 非敏感与敏感粪肠球菌的耐药率

LNSEFA对利奈唑胺的耐药率和中介率分别为68.8%和31.2%。LNSEFA对抗生素的耐药率多数高于利奈唑胺敏感粪肠球菌(linezolid sensitive E. faecalis, LSEFA),但对青霉素和呋喃妥因的耐药率略低于LSEFA。LNSEFA和LSEFA二者对四环素和红霉素的非敏感率高于90%,而LSEFA对红霉素的中介率为38.9%,高于LNSEFA。LNSEFA对氟喹诺酮类抗菌药物非敏感率约90%,对高浓度链霉素和庆大霉素的耐药率接近50%和70%,而LSEFA对氟喹诺酮类抗菌药物非敏感率约为40%,对高浓度链霉素和庆大霉素的非敏感率接近25%和40%。LNSEFA和LSEFA二者对磷霉素、青霉素G、呋喃妥因、氨苄西林非敏感率较低,对万古霉素非敏感率为0。具体见表4。

2.5 非敏感与敏感屎肠球菌的耐药率

LNSEFM对利奈唑胺的耐药率和中介率分别为69.2%和30.8%。LNSEFM对四环素、高浓度链霉素的耐药率高于利奈唑胺敏感屎肠球菌(linezolid sensitive E. faecium, LSEFM),对青霉素、氨苄西林、呋喃妥因、万古霉素耐药率低于LSEFM。LNSEFM和LSEFM二者对氟喹诺酮类抗菌药物的非敏感率约为100%,对青霉素、氨苄西林、红霉素非敏感率介于70%~100%,对高浓度庆大霉素的非敏感率约40%。LNSEFM对红霉素和呋喃妥因的中介率略高,分别为50%和33.3%。LNSEFM对万古霉素耐药率为0,而LSEFM对万古霉素耐药率为0.6%。具体见表5。

3 讨论

肠球菌感染在临床疾病中占据着重要地位,可引起严重后果。肠球菌是糖尿病足Wagner 4~5级溃疡中常见的革兰阳性菌(4级:34.48%, 5级:25.00%)[7]。肠球菌感染占人工关节感染的5.2% [8],且治疗失败率高于其他菌种感染[9]。肠球菌感染是医院获得性革兰阳性球菌血流感染28 d预后的独立危险因素之一[10],其引起的血流感染30 d病死率为21.4%~40%[11-13]。肠球菌菌血症最重要的并发症是感染性心内膜炎,死亡率为8.2%[11]。急性白血病患者发生肠球菌血流感染的比例可达27%(83/312),其中87%由屎肠球菌引起,13%由粪肠球菌引起,由此导致的死亡率为10%[14]。

根据我国CHINET监测网数据结果,近5年肠球菌属分离率占比为7%~9%,2018—2022年耐利奈唑胺粪肠球菌(linezolid resistant E. faecalis, LREFA)检出率分别为1.9%、2.3%、3.3%、3.5%和3.4%,耐利奈唑胺屎肠球菌(linezolid resistant E. faecium, LREFM)检出率分别为0.2%、0.3%、0.6%、0.4%和0.6%[4],两者均呈递增趋势,且LREFA检出率高于LREFM检出率,与本研究中LNSEFA检出率高于LNSEFM检出率的结果一致。本研究中LNSEFA检出率在2018年仍在较低水平,2019—2022年有较大增幅,检出率均高于6%,最高为2021年的13.1%。LNSEFM检出率自2018年0.5%上升到2019年1.1%后4年维持在1%~2%。本研究中LNSE检出率高于全国水平,一方面可能由于本研究统计的是非敏感肠球菌,包括耐药和中介菌株,而全国数据仅统计了耐药菌株;另一方面我院为三级甲等医院,耐药率可能高于全国二级和三级医院的平均水平。然而本研究中LNSEFA检出率却明显低于我国另一家三甲医院(22.0%,59/268)[15]。

LNSE检出在尿液中占比最高,其次为分泌物和引流液,与另一项研究粪肠球菌主要检出部位为尿液(45%)、伤口分泌物(19%)、血液(11%)、穿刺引流液(11%)的结果基本一致[15],另有研究表明尿路感染LNSEFA检出率为22.61%(26/115)[16]。此结果提示应重视这些标本中的肠球菌药敏结果,合理使用抗生素。

门诊是LNSE检出数量最多的科室,提示应关注从社区患者体内分离到肠球菌的利奈唑胺敏感性,合理调整抗生素的应用,同时这与通常认为的特殊耐药菌主要发生在院内的观点不一致,造成这种情况的原因有待进一步研究。泌尿外科、重症监护室和肛肠外科检出的肠球菌应同样提高警惕,避免抗生素不合理使用引起治疗失败。本研究LNSEFA对磷霉素、青霉素G、呋喃妥因和氨苄西林保持较高敏感性,对其他抗生素的敏感性较低,值得注意的是,LSEFA对四环素和红霉素的非敏感率同样较高,约90%,与LNSEFA相当。而LNSEFM仅对呋喃妥因敏感性略高,仍有33.3%的中介率,LSEFM仅对高浓度链霉素和四环素具有较高的敏感性。有文献报道,LRE对大环内酯类和氟喹诺酮类药物的耐药率为100%和89%[17],与本结果一致。本研究中LNSEFM对万古霉素耐药率为0,而LSEFM对万古霉素的耐药率为0.6%,未检测到耐利奈唑胺耐万古霉素肠球菌 (linezolid resistant vancomycin resistant Enterococcus, LRVRE)。然而在印度一篇研究中,LRVRE检出率高达14%(136/961),值得注意的是,LRVRE在血液中的检出率(25%)远高于尿液(13%)和脓液(13%)[18]。

西班牙对13株LREFA和6株LREFM的耐药机制进行研究表明,optrA和23S rDNA 中G2576T突变分别是导致粪肠球菌和屎肠球菌对利奈唑胺耐药的主要机制。在他们的研究中,12株粪肠球菌的optrA上游包括fexA,且两者可同时进行转移[17]。我国LRE中由于optrA基因导致的耐药较普遍,且通常optrA 引起的利奈唑胺MIC值相对较低(4~16 mg/L) [19-20]。另一项研究中,LNSEFA对利奈唑胺MIC值为4、8和16的菌株分别是80.8%(21/26)、15.4%(4/26)和3.8%(1/26),携带erm(A)的LNSEFA占比为86%[16]。LNSEFA主要型别为ST16,ST16型中31.42%(11/35)和ST179型中5.88%(2/34)为LNSEFA [16]。

有研究指出,LREFA检出率与同期万古霉素和利奈唑胺使用强度呈正相关,LREFM检出率与前6个月第四代头孢菌素使用强度呈正相关[21]。利奈唑胺年消耗剂量与CC58-LREFA、ST16-LREFA以及optrA基因检出率呈正相关,万古霉素年消耗剂量与CC58-LNSEFA、ST16-LNSEFA检出率显著相关[15]。留置导管和气管插管被认为是感染LNSEFA的独立预测因素[16],也有研究表明既往使用碳青霉烯类药物可能是LREFA感染的独立危险因素[19]。因为治疗LRE选择的抗菌药物有限,目前可采用与治疗VRE相似的噬菌体疗法[22]。

在一起由屎肠球菌引起的暴发事件中经调查发现,在键盘上分离到的菌株与患者菌株一致,说明肠球菌可在环境中传播[23],应警惕环境污染进而引起患者LNSE感染的暴发。

本研究存在以下几点不足:①此研究为单中心监测结果,应扩大监测范围,联合多家医疗机构进行多中心区域性长期监测;②未对LNSE的耐药机制和抗菌药物使用相关性进行研究,此部分内容将在后期工作中进行。

综上所述,由于目前对于LNSE的治疗选择非常有限,以及存在通过环境污染进行传播造成感染暴发的可能性,应加强对LNSE进行监测,合理使用利奈唑胺和万古霉素,减少LNSE的产生。

参 考 文 献

Agudelo Higuita N I, Huycke M M. Enterococcal disease, epidemiology, and implications for treatment. In: Gilmore M S, Clewell D B, Ike Y, et al. (ed), enterococci: From commensals to leading causes of drug resistant infection[M]. Boston: Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, 2014.

Leach K L, Brickner S J, Noe M C, et al. Linezolid, the first oxazolidinone antibacterial agent[J]. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2011, 1222(1): 49-54.

Bi R, Qin T, Fan W, et al. The emerging problem of linezolid-resistant enterococci[J]. J Glob Antimicrob Resist, 2018, 13: 11-19.

中国细菌耐药监测网CHINET.[EB/OL][2023-7-30]. http://www.chinets.com/Document/PageJump.

Mendes R E, Deshpande L, Streit J M, et al. ZAAPS programme results for 2016: An activity and spectrum analysis of linezolid using clinical isolates from medical centres in 42 countries[J]. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2018, 73(7): 1880-1887.

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing[S]. M100-S32. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2022.

Liu W, Song L, Sun W, et al. Distribution of microbes and antimicrobial susceptibility in patients with diabetic foot infections in South China[J]. Front Endocrinol, 2023, 14: 1113622.

Bjerke-Kroll B T, Christ A B, McLawhorn A S, et al. Periprosthetic joint infections treated with two-stage revision over 14 years: An evolving microbiology profile[J]. J Arthroplasty, 2014, 29(5): 877-882.

Senthi S, Munro J T, Pitto R P. Infection in total hip replacement: meta-analysis[J]. Int Orthop, 2011, 35(2): 253-260.

汪仕栋, 冯丹丹, 蒋昭清, 等. 医院获得性革兰阳性球菌血流感染的耐药性及预后影响因素分析[J]. 浙江临床医学, 2020, 22(3): 319-321.

Pinholt M, Ostergaard C, Arpi M, et al. Incidence, clinical characteristics and 30-day mortality of enterococcal bacteraemia in Denmark 2006—2009: A population-based cohort study[J]. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2014, 20(2): 145-151.

Hansen S G K," Roer L," Karstensen K T, et al. Vancomycin-sensitive Enterococcus faecium bacteraemia-hospital transmission and mortality in a Danish University Hospital [J]. J Med Microbiol, 2023, 72(7): 001731.

徐慧, 周华, 杨青, 等. 肠球菌属血流感染的临床特征及预后分析[J]. 浙江医学, 2018, 40(11): 1209-1212.

Messina J A, Sung A D, Chao N J, et al. The timing and epidemiology of Enterococcus faecium and E. faecalis bloodstream infections (BSI) in patients with acute leukemia receiving chemotherapy[J]. Blood, 2017, 130, Suppl_1: 1014.

Bai B, Hu K T, Zeng J, et al. Linezolid consumption facilitates the development of linezolid resistance in Enterococcus faecalis in a tertiary-care hospital: A 5-year surveillance study[J]. Microb Drug Resist, 2019, 25(6): 791-798.

Ma X, Zhang F, Bai B, et al. Linezolid resistance in Enterococcus faecalis associated with urinary tract infections of patients in a tertiary hospitals in China: Resistance mechanisms, virulence, and risk factors[J]. Front Public Health, 2021, 9: 570650.

Ruiz-Ripa L, Feßler A T, Hanke D, et al. Mechanisms of linezolid resistance among enterococci of clinical origin in Spain-detection of optrA- and cfr(D)-carrying E. faecalis[J]. Microorganisms, 2020, 8(8): 1155.

Jain S. Prevalence of linezolid-resistant vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus species (LRVRE) in clinical isolates from tertiary care hospital of north India-a real threat[J]. Int J Infect Dis, 2023, 130: S1-S35.

Chen M, Pan H, Lou Y, et al. Epidemiological characteristics and genetic structure of linezolid-resistant Enterococcus faecalis[J]. Infect Drug Resist, 2018, 11: 2397-2409.

Hua R, Xia Y, Wu W, et al. Molecular epidemiology and mechanisms of 43 low-level linezolid-resistant Enterococcus faecalis strains in Chongqing, China[J]. Ann Lab Med, 2019, 39(1): 36-42.

贾耀, 胡云英, 林美钦, 等. 2018—2021年某院抗菌药物使用强度与耐利奈唑胺肠球菌检出率动态相关性研究[J]. 解放军药学学报, 2022, 35(5): 434-438.

Bolocan A S, Upadrasta A, Bettio P H A, et al. Evaluation of phage therapy in the context of Enterococcus faecalis and its associated diseases[J]. Viruses, 2019, 11(4): 366.

Kim Y J, Hong M Y, Kang H M, et al. Using adenosine triphosphate bioluminescence level monitoring to identify bacterial reservoirs during two consecutive Enterococcus faecium and Staphylococcus capitis nosocomial infection outbreaks at a neonatal intensive care unit[J]. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control, 2023, 12(1): 68.