非酒精性脂肪性肝病流行现状及危险因素研究进展

2024-07-09许耀珑赵佳欣杨立刚

许耀珑 赵佳欣 杨立刚

【摘要】 非酒精性脂肪性肝病是一种进行性疾病,与乙型病毒性肝炎、丙型病毒性肝炎、酒精性肝病共同构成全球慢性肝病的主要病因。非酒精性脂肪性肝病若不进行有效干预,可逐渐恶化为非酒精性脂肪性肝炎、脂肪性肝纤维化、肝硬化甚至肝癌等,并可能在将来成为终末期肝病的主要原因。世界范围内,非酒精性脂肪性肝病的患病率、发病率正在不断增加,危害日趋显著。本文在进行大量资料搜集与文献阅读后,对非酒精性脂肪性肝病在性别、地区等方面的流行病学特征进行分析,同时针对激素、环境等危险因素对非酒精性脂肪性肝病可能造成的影响进行讨论,为非酒精性脂肪性肝病预防控制提供新的思路。

【关键词】 非酒精性脂肪性肝病;流行病学;危险因素;综述

【中图分类号】 R 575.5 【文献标识码】 A DOI:10.12114/j.issn.1007-9572.2023.0893

Epidemic Status and Risk Factors of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

XU Yaolong,ZHAO Jiaxin,YANG Ligang*

Key Laboratory of Environmental Medicine Engineering(Southeast University),Ministry of Education/Department of Nutrition and Food Hygiene,School of Public Health,Southeast University,Nanjing 210003,China

*Corresponding author:YANG Ligang,Associate professor;E-mail:yangligang2012@163.com

【Abstract】 Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease(NAFLD) is a progressive disease. NAFLD,viral hepatitis B,viral hepatitis C,and alcoholic liver disease are the major cause of chronic liver disease in the world. Without effective intervention measures,NAFLD can gradually deteriorate to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis,fatty liver fibrosis,liver cirrhosis and even hepatocellular carcinoma,and may become the main cause of end-stage liver disease in the future. The prevalence and incidence of NAFLD are increasing in the world,and the problem is becoming more and more serious. On the basis of relevant data collection and literature research,this article analyzes the epidemiological characteristics in gender and region of NAFLD,and discusses the possible effects of hormones and environment,and other risk factors on NAFLD,so as to provide new ideas for the prevention and control of NAFLD.

【Key words】 Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease;Epidemiology;Risk factors;Review

非酒精性脂肪性肝病(NAFLD)是指在除外酒精和其他明显损肝因素的情况下,肝细胞内表现出来的弥漫性脂肪沉积并逐渐发展恶化为明显的脂肪变性以及肝细胞炎症的一种临床病理综合征,包括一系列不同损伤程度和纤维化程度的肝脏病变[1]。NAFLD作为一个重要的公共卫生问题,其患病率高、发病率高、对公众健康影响严重。随着研究的开展,人们也发现NAFLD除了会引起肝硬化、肝癌等肝脏疾病(非硬化性NAFLD肝癌发病率为(0.01~0.13)/100人·年,肝硬化早期NAFLD肝癌发病率约为0.03/100人·年,肝硬化NAFLD肝癌发病率约为3.78/100人·年[2-4]),还会增加其他多种慢性疾病比如2型糖尿病(T2DM)、心血管疾病(CVD)、心脏病、多囊卵巢综合征(PCOS)、慢性肾脏疾病(CKD)、阻塞性睡眠呼吸暂停(OSA)、骨质疏松等的发病风险并引起死亡[5-6]。

1 NAFLD的流行现状

1.1 NAFLD的患病率和发病率存在性别差异

RIAZI等[7]进行的Meta分析中,研究人员对17个国家共包含的1 030 160个样本进行患病率估计,截至2021年5月,全球NAFLD患病率为32.4%(95%CI=29.9%~34.9%),其中男性患病率为39.7%(95%CI=36.6%~42.8%),显著高于女性的25.6%(95%CI=22.3%~28.8%)。同时对NAFLD的群体发病率进行估计,全世界范围内NAFLD发病率为46.9/1 000人·年(95%CI=36.4~57.5),男性发病率(70.8/1 000人·年)显著高于女性(29.6/1 000人·年)。NAFLD患病率与发病率存在明显的性别差异,关于该现象的形成,很有可能是因为雌激素对NAFLD患病具有保护作用,使女性的相对易感性减弱,这一说法也很好地解释了为什么男性和绝经期妇女的NAFLD患病率要显著高于尚未绝经的女性[8]。

1.2 NAFLD的患病率与发病率存在明显的种族、地区差异

除了熟知的性别差异外,NAFLD在患病率方面存在明显的种族差异和地区差异[9-10]。在一项系统评价中,研究人员对1990—2019年的NAFLD患病率进行统计,发现拉丁美洲(44.37%)、中东和北非(36.53%)等地NAFLD患病率明显高于世界其他地区(同时期世界平均患病率为30.69%,其他地区患病率比如东亚为29.71%,亚太地区为28.02%,西欧为25.1%)[10]。

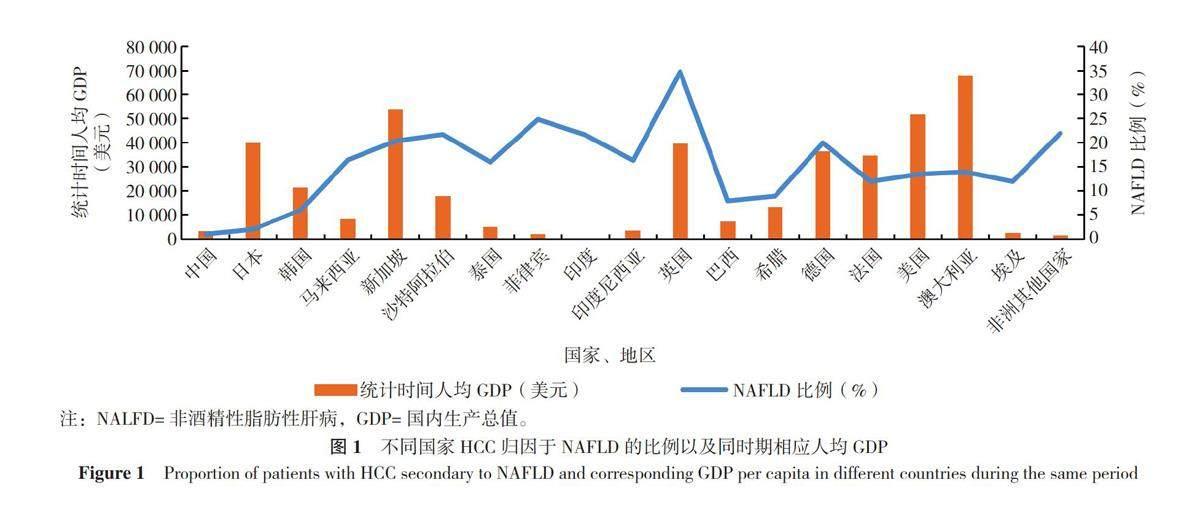

NAFLD与BMI的关联强度也表现出强烈的种族差异。ZHOU等[11]分析发现,与美国的BMI水平相比,即使中国平均BMI水平在低得多的情况下,国民NAFLD患病率也高于美国,国民对NAFLD的发病风险较美国更高。同时,NAFLD与肝癌的关联强度也表现出一定的种族、地区特异性,具体表现为不同国家、地区的肝细胞癌(HCC)患者归因于NAFLD发展的比例(以下简称“NAFLD比例”)不尽相同[3,12-27](表1)。对不同国家、地区NAFLD比例以及统计时间中期的人均国内生产总值(GDP)进行作图分析,发现NAFLD比例与该地人均GDP大致呈负相关(图1),其原因尚不明确,但已有不少研究表明肝癌以及NAFLD发生率与地区经济发展水平大致呈正相关性[11,28-29],因此作者认为在人均GDP较高的国家NAFLD比例较低,可能是因为该地区医疗水平较高使得肝癌最主要的原因依然来源于病毒感染。从数据中可以发现,NAFLD比例相对较高的国家主要有英国、德国、非洲国家和一些南亚、东南亚国家。其中英国和德国高人均GDP同时伴随高NAFLD比例,并与前期研究结果有巨大差异(英国2000年统计NAFLD比例不足10%,德国1988—1999年统计NAFLD比例为7%[3]),关于该现象研究人员仅对不同文献中NAFLD的判断标准对NAFLD比例的影响进行了讨论,但并未解释造成巨大差异的具体原因。非洲国家和南亚、东南亚国家,即使NAFLD比例较高,但病毒感染仍然是肝癌的最主要原因[比如埃及肝癌最常见的原因是丙型肝炎病毒感染(84%),尼日利亚、加纳肝癌最常见的原因是乙型肝炎病毒感染(55%)[30]],同时,这些地区高NAFLD比例还可能与该地所处气候炎热以及居民高肥胖率有一定关系[31-33]。需要关注的是,相比于美国,即使中国居民在同等BMI水平下患NAFLD的风险较大,但肝癌归因于此的比例却相当小。基因与饮食习惯对NAFLD比例也可能存在一定的影响,比如东亚地区,即使经济发展存在差异,但中国与日本、韩国的 NAFLD 比例与其他地区相比明显更低;位处亚热带的中国台湾地区(比例仅为5%)与部分南亚、东南亚地区相比,NAFLD比例也明显低得多[12];基因与饮食习惯对NAFLD比例影响的重要性需要进一步论证。

1.3 中国NAFLD的流行趋势

据ZHOU等[11]的分析,过去20年,由于生活方式上的转变,NAFLD在中国的患病率有明显的上升趋势:中国NAFLD患病率从2000年的23.8%(95%CI=16.4%~31.2%),开始缓慢增长并在2010年增长加速,到2018年,全国NAFLD患病率达到32.9%(95%CI=28.9%~36.8%)。对该段时间的患病率增长趋势分析发现:NAFLD患病率上升与肥胖症患病率上升趋势并行(中国肥胖症患病率从2000年的2%上升到2014年的7%),NAFLD患病率增加与人均GDP增长有较大的正相关性;此两条结论在美国也有着一定程度的体现。

在中国,NAFLD发病率逐年递增:2007—2011年NAFLD发病率为4.2%(95%CI=2.3%~6.0%),2011—2013年发病率为4.6%(95%CI=3.3%~6.0%),2014—2016年发病率增加为5.2%(95%CI=3.9%~6.5%),明显超过了同期美国NAFLD的发病率(由2.32%增加至4.26%)[11]。根据以上数据推断,2030年中国大陆NAFLD病例数很有可能超过3.146亿,其相关肝硬化病例数将增长112.8%,相关肝癌数量将增加86%,将成为世界上NAFLD患病率增幅以及患病人数最多的国家[11],其带来的经济负担和健康损害不言而喻。

2 NAFLD的危险因素

对于NAFLD的发生发展,目前已证实基因、代谢综合征、饮食结构等,在病理病机中发挥了关键作用。

基因方面,在一项系统评价中,研究者列举了几个对NAFLD发生发展起关键作用的基因组并讨论其功能,比如PNPLA3、TM6SF2、GCKR、MBOAT7、SOD2等[34],并认为这些基因的存在以及部分序列突变,通过不同机制增加了NAFLD的发病风险。而不同种族之间NAFLD的发病风险不同,可能与基因表达存在一定联系,比如在SANTORO等[35]对肥胖和青少年的队列研究中,就讨论了PNPLA3I148M和GCKRP446L的综合效应对NAFLD的影响。

代谢方面,有学者认为机体患有代谢综合征是个体患NAFLD的最强危险因素[1]:代谢综合征以内脏肥胖为主要效应因素,而内脏肥胖又与肝脂肪浸润密切相关,肝脏若无明显外酒精损伤,则最终表现为NAFLD。同时NAFLD引起的代谢异常又会增加机体患有其他代谢综合征的风险,这在NAFLD合并CVD的发展中表现得极为突出:NAFLD患者易发CVD,与单纯性脂肪肝发展为脂肪性肝炎的过程中患者体内发生的糖代谢紊乱以及胰岛素抵抗密切相关,患者产生胰岛素抵抗,机体代谢异常表现的血脂异常、高血糖、氧化应激、炎症激活、内皮功能障碍和异位脂质积累,共同创造了有利于CVD发展的促动脉粥样硬化环境[36]。在这样的作用下,NAFLD患者群体较健康人群更易伴发动脉高血压、冠状动脉粥样硬化、心律失常(如心房颤动和室性心律失常)、结构性心脏病(如心肌重塑引起的心脏泵血功能障碍和主动脉瓣、左房室瓣钙化)等心血管合并症[37],给临床治疗带来极大的不便。总体而言,NAFLD与代谢综合征二者之间的作用是相互的,个体患有代谢综合征不仅会增加患NAFLD的风险,同时NAFLD也可能会伴发或增强其他几种代谢综合征。代谢综合征既是NAFLD的一个强危险因素,也是NAFLD病程发展中伴随的结果[38]。

饮食结构方面,研究人员发现NAFLD组在宏量营养素的摄入模式上与对照组没有显著差异,但在总热量摄入上显著升高,同时也发现NAFLD组在饱和脂肪、果糖和胆固醇等几种食物成分的摄入量上与对照组存在差异[39-41],这些食物成分的大量摄入与NAFLD的发生密切相关。

除基因、代谢、饮食外,研究人员也开始关注生活方式、肠道菌群、性激素水平、气候变化及环境污染对NAFLD的影响。

2.1 生活方式对NAFLD的影响

在一项孟德尔随机化研究(MR)中,YUAN等[42]对常见的不良生活习惯比如吸烟、食用咖啡、饮酒、剧烈运动等,与NAFLD发生风险之间的联系进行了讨论,并得出了以下结论。

吸烟将增加NAFLD的发病风险。在一项队列研究中,研究者就儿童及成年人被动吸烟情况展开调查,发现在人发育的不同时期,被动吸烟均将增加个体NAFLD的发病风险(RR儿童=1.41,RR成人=1.35)[43],而在其他队列研究中,也得出了相似的结论,并认为每年吸烟量与NAFLD风险比存在一定的剂量关系[44-45]。吸烟与NAFLD的背后联系可能与长期吸烟以及尼古丁使用所诱导的胰岛素抵抗、高胰岛素血症、血脂异常、氧化应激损伤以及组织低氧血症等有关[46]。

习惯性食用咖啡可以降低NAFLD的发病风险[47-48]。但目前而言,咖啡摄入与NAFLD风险降低的具体剂量关系以及作用机制有待进一步研究[48],关于咖啡摄入对NAFLD保护作用机制的猜想,主要集中在两个方面。一方面咖啡的摄入可以增加机体的产热作用以及能量消耗,以达到减重的作用;该结论在一些肥胖和T2DM患者中得到了验证[49];同时增加能量消耗也是剧烈运动可以降低NAFLD发生风险的重要原因[42]。另一方面咖啡的摄入可以增强机体胰岛素的分泌以及敏感性从而改善机体代谢预防NAFLD的发生与恶化[50]。除此之外,咖啡带来的其他作用比如降低活性氧产生[51]、改善细胞炎性表达[52]、改变肠道菌群结构[53]等,也可对NAFLD发生发展起一定保护作用。目前还发现一定量的咖啡摄入甚至可以降低NAFLD发展中肝细胞纤维化程度,降低HCC的发生风险,并有学者在Meta分析中给出了具体的剂量关系[54],认为在肝癌保护中咖啡因是主要作用物质[54]。但咖啡因对肝癌的预防作用存在巨大争论,一方面不含咖啡因的咖啡即使可以降低肝癌发生风险但效用小于含咖啡因的咖啡[54];另一方面其他含咖啡因的饮料比如绿茶,却没有发现降低肝癌发生风险的功效[55-56]。总体而言,咖啡对NAFLD的保护、咖啡因对肝癌的预防,具体机制以及剂量关系尚未明确,但功效已有证据证实。日常食用咖啡,虽然会增加胆固醇水平,CVD风险却并未升高[57],这对一些由代谢水平失调引起的慢性疾病有明显的帮助,也正因如此,欧洲肝脏研究学会(EASL)建议患有慢性肝病的患者,可以日常饮用咖啡以降低患肝癌的风险。

饮酒对NAFLD的影响存在争论。一些学者在其研究中发现轻、中度饮酒可以降低NAFLD风险[58],但在对NAFLD患者的随访研究中又得出了适度饮酒人群在NAFLD的状况改善方面要差于不饮酒人群的结论[59],甚至还有学者认为饮酒会增加肝硬化的风险[60]。饮酒对于NAFLD发展的复杂作用提示,所谓的适度饮酒对于NAFLD的影响效果可能存在一个量的临界值[42],饮酒量在临界值的两端对于NAFLD发病风险的作用有较大差异。但也有学者质疑,所谓的“量的临界值”对于描述酒精消费对NAFLD的作用并不准确,自我报告饮酒量的不准确、回忆偏倚、受试者对饮酒的漏报或者不报以及对于饮酒不同标准的界定,将对酒精消费效用研究产生影响[61]。

总之,一些健康积极的生活方式比如尽早戒烟、保持正常BMI、低饮酒量、地中海饮食、适度体育锻炼、保持充足睡眠等,可有效预防NAFLD的发生。

2.2 肠道菌群通过“肠-肝轴”影响NAFLD的发生发展

肠道菌群是一类寄居在人胃肠道内的细菌共生群体,其产生的代谢废物及生成产物,通过“肠-肝轴”,从肠道运输至肝脏并发挥作用,从而影响机体代谢,使肠道菌群与NAFLD发生发展密切相关[62-63]。正常情况下,肠道菌群可以和宿主及外部环境建立动态的生态平衡,通过参与小分子代谢传递信号,发挥至关重要的生理生化以及免疫作用,比如食物消化、合成必需维生素、刺激和调节免疫系统、排除病原体、清除毒素和致癌物、支持肠道功能等[64]。当机体内外环境遭受重大改变时,肠道菌群失衡影响机体信号调节,影响肝脏糖脂代谢,增加肝脏内脂肪堆积;或是转化、生成对机体有毒害作用的物质比如甲胺[后将继续转化为三甲胺-氮氧化物(TMAO)]、内毒素、内源性乙醇等,破坏肠道屏障功能、影响肝细胞通透性、加重肝细胞内脂肪沉积、诱导恶化肝细胞炎症反应,从而影响NAFLD的进程[65-68]。

健康人群与NAFLD人群中,肠道菌群的结构存在明显不同,一些可以引起炎症的致病菌属如埃希菌属(Escherichia)、拟杆菌属(Bacteroides)、高产酒精肺炎克雷伯菌(Klebsiella pneumoniae)、瘤胃球菌(Ruminococcus)等在患者肠道内丰度增加或检出率增高,而能够参与肠道正常代谢的菌属比如普雷沃氏菌属(Prevotella)、乳酸杆菌属(Lactobacillus)等丰度有所下降[69-73]。基于肠道菌群在不同病理情况下结构的改变,其既可做非侵入性生物诊断物进行疾病程度的评估,也可用做一些慢性疾病比如NAFLD的治疗,该方法性价比高、不良反应少,在将来进行深入研究探明其具体作用机制、剂量、剂型等因素后,也许可成为治疗NAFLD乃至其他慢性疾病的新方法[74-75]。

2.3 激素水平可能影响NAFLD的发病风险

流行病学调查显示,男性NAFLD患病率显著高于女性,但对于绝经期妇女而言该差异明显变小,并且男、女性NAFLD发病率在不同年龄阶段存在差异[7-8,76-77],体内性激素水平可能对NAFLD的发生发展起到了一定的调控作用。肝脏作为一个重要的代谢器官以及性激素靶器官,雌激素对NAFLD预防的积极作用已被证实,一般认为雌激素可通过以下机制调节NAFLD的发生:雌激素通过雌激素受体α(ERα)降低三酰甘油含量、调控肝脏基因表达以降低肝脏新生脂肪生成、减少肝脏脂肪堆积、抑制游离脂肪酸向肝脏转运、抑制胰岛素抵抗的发生[78],以上机制共同对预防NAFLD起到了积极作用。雄激素的影响还需进一步论证,目前研究结果主要集中在两个方面:在男性中,内源性总睾酮减少与胰岛素抵抗、机体肥胖、肝脏脂肪堆积密切相关;但在女性中,高雄激素血症引起的作用刚好相反[79],关于该现象形成的原因以及雄激素在NAFLD病理机制中的作用,还有待进一步研究。

2.4 环境污染与气候恶化加重了NAFLD的发病风险

研究发现,气候恶化与NAFLD患病率增加有一定的关联,全球变暖可能引起NAFLD的发生[31,80-81]。基于此,有学者给出了这样的解释:温度升高,人体产热减少,代谢水平降低,更容易肥胖;处于温暖环境中的人,将获得更多的食物中的热量;气候变暖引起粮食不安全,诱发了居民的不健康饮食结构,使热量摄入过剩;气候变暖减少了居民体育活动的强度,降低其能量消耗[32,82-83];以上各种因素,共同为NAFLD发病创造了有利环境。

同时人们还发现环境污染物也会通过一定的作用途径增加NAFLD的发病风险,这意味着改善环境、控制气候变暖或许是世界范围内预防控制NAFLD患病率和发病率持续上升的一种办法。此处简要介绍几种常见的环境污染物及其影响机制。

一些可以在人体内持续存在并且干扰内分泌的化学物质,将增加机体患NAFLD的风险,比如全氟烷基物和多氟烷基物,可以凭借自身对肝脏的毒性以及其难以代谢清除的特性,持久地损害肝细胞、干扰激素信号传导、影响内分泌调节、激发免疫应答从而诱导机体免疫代谢紊乱、肝细胞炎性浸润、纤维化发展甚至肝细胞凋亡,增加发病风险和促进肝脏炎症的发展[84-85]。具有相似作用机制的还有有机氯农药比如DDT[81]、双酚A[86]和二噁英[87]等。

大气污染、特殊职业环境暴露以及食用煎烤油炸食物等方式进入体内的多环芳烃,主要通过两条途径对肝脏产生毒害作用并影响机体能量代谢。一方面,摄入体内的多环芳烃可在肝脏代谢中产生环氧化物、醌和酚类等物质,进一步产生对肝脏有强毒性的活性氧(ROS),从而引起肝细胞氧化应激,增加NAFLD发病风险并诱导肝脏的炎症和损伤[88]。另一方面,目前研究发现苯并芘(BaP,多环芳烃的一种)可以导致雌激素代谢酶细胞色素P450 1A1的过表达,抑制雌激素信号通路传导,致使肝脏内脂肪酸氧化受阻、三酰甘油向肝外运输减少、外周脂肪动员增加,共同造成了肝脏的脂肪沉积,增加NAFLD的发病风险[88]。但需要注意的是,BaP主要影响雌激素信号传导通路,因此对于女性而言作用更加明显,会抑制雌激素正常情况下对NAFLD患病的保护作用,但BaP对于雄激素传导通路的影响,目前还缺少相应研究。

重金属对人体的损伤作用早有研究,目前已证实重金属可延食物链积累,在人体内产生生物富集现象并对机体有着极大的毒害作用:在代谢过程中可引起氧化应激破坏脂质、蛋白质和DNA分子结构,导致细胞损伤、变异甚至癌变,从而引起消化系统、呼吸系统、心血管系统、泌尿生殖系统、神经系统和机体造血系统的损伤疾病[89]。在许多人群研究和队列研究中就已经发现,由于工业排放、土壤污染、食物水源摄入的重金属镉(Cd)、铅(Pb)以及类金属砷(As)等,均与NAFLD发病风险增加有关,并认为尿Cd、血Pb以及尿As水平的升高,与NAFLD发生风险呈正相关[81,90-94]。重金属在NAFLD发生发展中主要通过发生在线粒体中的氧化损伤,促进肝细胞内的脂质合成、沉积并抑制脂质分解代谢,引起肝细胞脂肪变性;氧化应激引起的肝细胞损伤又会不同程度地诱发肝细胞炎症、凋亡、再生、纤维化,促进NAFLD向非酒精性脂肪性肝炎(NASH)发展[95-97]。重金属暴露还存在一定的累积效应,联合暴露几种重金属会进一步增加NAFLD和相关并发症的发病风险[98]。

塑料产品在使用制造降解过程中产生的微小颗粒——微塑料(MPs,颗粒尺寸1 μm~5 mm)和纳米塑料(NPs,颗粒尺寸<1 μm),也被认为与NAFLD风险增加有关[99-100]。塑料微粒主要通过海鲜及水源进入人体消化道,在被肠道吸收或是肠道表皮浸润后,通过血液进入肝脏,而后经由细胞内吞作用或是其他被动扩散方式进入肝细胞内并产生积聚,改变肝脏形态、影响肝脏生理功能[101]。MPs/NPs由于自身化学物质成分而具有的肝毒性以及难降解性,还会进一步促进肝脏损伤、增加肝细胞的炎症表达[102]。研究发现,在人体肝脏中发现的直径为1 μm的聚苯乙烯微珠,能通过增加HNF4A的表达来破坏脂质代谢,改变ATP产生,促进ROS生成,诱导细胞色素P450 CYP2E1的氧化应激,引起肝脏炎症、氧化损伤、脂毒性、肝毒性,并最终影响NAFLD的发生发展[103]。而其他研究还发现,MPs以及NPs进入肝脏后,还可以通过改变参与脂质代谢基因比如PPARα或PPARγ的表达,引起肝脏内脂肪的沉积[104]。总体而言,塑料微粒通过多个机制对肝脏代谢功能产生影响,增加NAFLD的发病风险。

空气颗粒物对呼吸系统易造成严重的损伤,其中PM2.5被认为对人体的危害最大[105],但越来越多的证据证实,空气颗粒物还会增加NAFLD的发生风险,加重NAFLD患者的代谢紊乱和炎症功能障碍,促进NAFLD向NASH发展[105-107]。PM2.5进入呼吸系统穿过肺泡屏障后,可以经由体循环随血液进入肝脏,在代谢途中可产生ROS引起肝细胞氧化应激损伤细胞、可抑制PPARα和PPARγ基因的表达增加脂质积聚,可促进细胞因子分泌加重细胞炎性表达,可引起肠道菌群结构变化甚至失衡进一步加重机体代谢紊乱,最终导致NAFLD的发病甚至恶化[108-111]。关于空气颗粒物代谢方面的研究还发现,不同性别对于长期暴露于PM2.5中产生代谢影响的敏感性不同,雌性小鼠表现出更高的NAFLD发病率、肝三酰甘油含量、游离脂肪酸含量、胆固醇水平等[112],具体原因尚不明确。

3 总结与展望

NAFLD由多方面因素引起,其主要病理学机制为肝细胞的结构和功能受损,从而引发肝脂肪变性和肝炎,最终导致肝硬化、肝衰竭和肝癌的发生,同时患者还患有多种代谢并发症,给社会带来严重的经济负担和医疗负担。在NAFLD的患病率与发病率居高不下的背景下,针对NAFLD的危险因素,如何采取经济有效的预防治疗措施,未来如何降低其发病率与患病率,如何提高患病群体的生存质量,是一个重要的公共卫生问题。

作者贡献:许耀珑负责文章的构思与设计,资料整理分析,数据收集,论文撰写;赵佳欣负责数据收集,绘制表格,论文修订;杨立刚负责论文修订与审校,负责最终版本修订,对论文负责。

本文无利益冲突。

杨立刚:https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4027-1580

参考文献

FRIEDMAN S L,NEUSCHWANDER-TETRI B A,RINELLA M,et al. Mechanisms of NAFLD development and therapeutic strategies[J]. Nat Med,2018,24(7):908-922. DOI:10.1038/s41591-018-0104-9.

ITO T,ISHIGAMI M,ISHIZU Y,et al. Utility and limitations of noninvasive fibrosis markers for predicting prognosis in biopsy-proven Japanese non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol,2019,34(1):207-214. DOI:10.1111/jgh.14448.

HUANG D Q,EL-SERAG H B,LOOMBA R. Global epidemiology of NAFLD-related HCC:trends,predictions,risk factors and prevention[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol,2021,18(4):223-238. DOI:10.1038/s41575-020-00381-6.

ORCI L A,SANDUZZI-ZAMPARELLI M,CABALLOL B,et al. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease:a systematic review,meta-analysis,and meta-regression[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol,2022,20(2):283-292.e10. DOI:10.1016/j.cgh.2021.05.002.

KAYA E D,YILMAZ Y. Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease(MAFLD):a multi-systemic disease beyond the liver[J]. J Clin Transl Hepatol,2022,10(2):329-338. DOI:10.14218/JCTH.2021.00178.

YE Q,ZOU B Y,YEO Y H,et al. Global prevalence,incidence,and outcomes of non-obese or lean non-alcoholic fatty liver disease:a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol,2020,5(8):739-752. DOI:10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30077-7.

RIAZI K,AZHARI H,CHARETTE J H,et al. The prevalence and incidence of NAFLD worldwide:a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol,2022,7(9):851-861. DOI:10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00165-0.

LONARDO A,NASCIMBENI F,BALLESTRI S,et al. Sex differences in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease:state of the art and identification of research gaps[J]. Hepatology,2019,70(4):1457-1469. DOI:10.1002/hep.30626.

ESTES C,ANSTEE Q M,ARIAS-LOSTE M T,et al. Modeling NAFLD disease burden in China,France,Germany,Italy,Japan,Spain,United Kingdom,and United States for the period 2016-2030[J]. J Hepatol,2018,69(4):896-904. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2018.05.036.

YOUNOSSI Z M,GOLABI P,PAIK J M,et al. The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease(NAFLD)and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis(NASH):a systematic review[J]. Hepatology,2023,77(4):1335-1347. DOI:10.1097/HEP.0000000000000004.

ZHOU J H,ZHOU F,WANG W X,et al. Epidemiological features of NAFLD from 1999 to 2018 in China[J]. Hepatology,2020,71(5):1851-1864. DOI:10.1002/hep.31150.

PARK J W,CHEN M S,COLOMBO M,et al. Global patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma management from diagnosis to death:the BRIDGE Study[J]. Liver Int,2015,35(9):2155-2166. DOI:10.1111/liv.12818.

TOKUSHIGE K,HASHIMOTO E,HORIE Y,et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Japanese patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease,alcoholic liver disease,and chronic liver disease of unknown etiology:report of the nationwide survey[J]. J Gastroenterol,2011,46(10):1230-1237. DOI:10.1007/s00535-011-0431-9.

GOH K L,RAZLAN H,HARTONO J L,et al. Liver cancer in Malaysia:epidemiology and clinical presentation in a multiracial Asian population[J]. J Dig Dis,2015,16(3):152-158. DOI:10.1111/1751-2980.12223.

LIEW Z H,GOH G B,HAO Y,et al. Comparison of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cryptogenic versus hepatitis B etiology:a study of 1079 cases over 3 decades[J]. Dig Dis Sci,2019,64(2):585-590. DOI:10.1007/s10620-018-5331-x.

ALJUMAH A A,KURIRY H,ALZUNAITAN M,et al. Clinical presentation,risk factors,and treatment modalities of hepatocellular carcinoma:a single tertiary care center experience[J]. Gastroenterol Res Pract,2016,2016:1989045. DOI:10.1155/2016/1989045.

SOMBOON K,SIRAMOLPIWAT S,VILAICHONE R K. Epidemiology and survival of hepatocellular carcinoma in the central region of Thailand[J]. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev,2014,15(8):3567-3570. DOI:10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.8.3567.

YUEN M F,HOU J L,CHUTAPUTTI A,et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the Asia Pacific region[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol,2009,24(3):346-353. DOI:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05784.x.

PAUL S B,CHALAMALASETTY S B,VISHNUBHATLA S,et al. Clinical profile,etiology and therapeutic outcome in 324 hepatocellular carcinoma patients at a tertiary care center in India[J]. Oncology,2009,77(3/4):162-171. DOI:10.1159/000231886.

JASIRWAN C O M,HASAN I,SULAIMAN A S,et al. Risk factors of mortality in the patients with hepatocellular carcinoma:a multicenter study in Indonesia[J]. Curr Probl Cancer,2020,44(1):100480. DOI:10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2019.05.003.

DYSON J,JAQUES B,CHATTOPADYHAY D,et al. Hepatocellular cancer:the impact of obesity,type 2 diabetes and a multidisciplinary team[J]. J Hepatol,2014,60(1):110-117. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2013.08.011.

LOPES F D E L,COELHO F F,KRUGER J A,et al. Influence of hepatocellular carcinoma etiology in the survival after resection[J]. Braz Arch Dig Surg,2016,29(2):105-108. DOI:10.1590/0102-6720201600020010.

RAPTIS I,KOSKINAS J,EMMANOUIL T,et al. Changing relative roles of hepatitis B and C viruses in the aetiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Greece. Epidemiological and clinical observations[J]. J Viral Hepat,2003,10(6):450-454. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00442.x.

GANSLMAYER M,HAGEL A,DAUTH W,et al. A large cohort of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in a single European centre:aetiology and prognosis now and in a historical cohort[J]. Swiss Med Wkly,2014,144:w13900. DOI:10.4414/smw.2014.13900.

PAIS R,FARTOUX L,GOUMARD C,et al. Temporal trends,clinical patterns and outcomes of NAFLD-related HCC in patients undergoing liver resection over a 20-year period[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther,2017,46(9):856-863. DOI:10.1111/apt.14261.

WONG R J,CHEUNG R,AHMED A. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the most rapidly growing indication for liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the U.S.[J]. Hepatology,2014,59(6):2188-2195. DOI:10.1002/hep.26986.

HONG T P,GOW P,FINK M,et al. Novel population-based study finding higher than reported hepatocellular carcinoma incidence suggests an updated approach is needed[J]. Hepatology,2016,63(4):1205-1212. DOI:10.1002/hep.28267.

SEYDA SEYDEL G,KUCUKOGLU O,ALTINBASV A,

et al. Economic growth leads to increase of obesity and associated hepatocellular carcinoma in developing countries[J]. Ann Hepatol,2016,15(5):662-672. DOI:10.5604/16652681.1212316.

ZHU J Z,ZHOU Q Y,WANG Y M,et al. Prevalence of fatty liver disease and the economy in China:a systematic review[J]. World J Gastroenterol,2015,21(18):5695-5706. DOI:10.3748/wjg.v21.i18.5695.

YANG J D,MOHAMED E A,AZIZ A O,et al. Characteristics,management,and outcomes of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Africa:a multicountry observational study from the Africa Liver Cancer Consortium[J]. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol,2017,2(2):103-111. DOI:10.1016/S2468-1253(16)30161-3.

FANZO J C,DOWNS S M. Climate change and nutrition-associated diseases[J]. Nat Rev Dis Primers,2021,7(1):90. DOI:10.1038/s41572-021-00329-3.

KOCH C A,SHARDA P,PATEL J,et al. Climate change and obesity[J]. Horm Metab Res,2021,53(9):575-587. DOI:10.1055/a-1533-2861.

BL?HER M. Obesity:global epidemiology and pathogenesis[J]. Nat Rev Endocrinol,2019,15(5):288-298. DOI:10.1038/s41574-019-0176-8.

PAFILI K,RODEN M. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease(NAFLD)from pathogenesis to treatment concepts in humans[J]. Mol Metab,2021,50:101122. DOI:10.1016/j.molmet.2020.101122.

SANTORO N,ZHANG C K,ZHAO H Y,et al. Variant in the glucokinase regulatory protein(GCKR)gene is associated with fatty liver in obese children and adolescents[J]. Hepatology,2012,55(3):781-789. DOI:10.1002/hep.24806.

STENDER S,KOZLITINA J,NORDESTGAARD B G,et al. Adiposity amplifies the genetic risk of fatty liver disease conferred by multiple loci[J]. Nat Genet,2017,49(6):842-847. DOI:10.1038/ng.3855.

KASPER P,MARTIN A,LANG S,et al. NAFLD and cardiovascular diseases:a clinical review[J]. Clin Res Cardiol,2021,110(7):921-937. DOI:10.1007/s00392-020-01709-7.

RADU F,POTCOVARU C G,SALMEN T,et al. The link between NAFLD and metabolic syndrome[J]. Diagnostics,2023,13(4):614. DOI:10.3390/diagnostics13040614.

KWAK J H,JUN D W,LEE S M,et al. Lifestyle predictors of obese and non-obese patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease:a cross-sectional study[J]. Clin Nutr,2018,37(5):1550-1557. DOI:10.1016/j.clnu.2017.08.018.

KO E,YOON E L,JUN D W. Risk factors in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease[J]. Clin Mol Hepatol,2023,29(Suppl):S79-85. DOI:10.3350/cmh.2022.0398.

ENG J M,ESTALL J L. Diet-induced models of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease:food for thought on sugar,fat,and cholesterol[J]. Cells,2021,10(7):1805. DOI:10.3390/cells10071805.

YUAN S,CHEN J,LI X,et al. Lifestyle and metabolic factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease:mendelian randomization study[J]. Eur J Epidemiol,2022,37(7):723-733. DOI:10.1007/s10654-022-00868-3.

WU F T,PAHKALA K,JUONALA M,et al. Childhood and adulthood passive smoking and nonalcoholic fatty liver in midlife:a 31-year cohort study[J]. Am J Gastroenterol,2021,116(6):1256-1263. DOI:10.14309/ajg.0000000000001141.

MUMTAZ H,HAMEED M,SANGAH A B,et al. Association between smoking and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Southeast Asia[J]. Front Public Health,2022,10:1008878. DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2022.1008878.

JUNG H S,CHANG Y,KWON M J,et al. Smoking and the risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease:a cohort study[J]. Am J Gastroenterol,2019,114(3):453-463. DOI:10.1038/s41395-018-0283-5.

PREMKUMAR M,ANAND A C. Tobacco,cigarettes,and the liver:the smoking Gun[J]. J Clin Exp Hepatol,2021,11(6):700-712. DOI:10.1016/j.jceh.2021.07.016.

HAYAT U,SIDDIQUI A A,OKUT H,et al. The effect of coffee consumption on the non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and liver fibrosis:a meta-analysis of 11 epidemiological studies[J]. Ann Hepatol,2021,20:100254. DOI:10.1016/j.aohep.2020.08.071.

ZHANG Y,LIU Z P,CHOUDHURY T,et al. Habitual coffee intake and risk for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease:a two-sample Mendelian randomization study[J]. Eur J Nutr,2021,60(4):1761-1767. DOI:10.1007/s00394-020-02369-z.

SANTOS R M M,LIMA D R A. Coffee consumption,obesity and type 2 diabetes:a mini-review[J]. Eur J Nutr,2016,55(4):1345-1358. DOI:10.1007/s00394-016-1206-0.

LOOPSTRA-MASTERS R C,LIESE A D,HAFFNER S M,

et al. Associations between the intake of caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee and measures of insulin sensitivity and beta cell function[J]. Diabetologia,2011,54(2):320-328. DOI:10.1007/s00125-010-1957-8.

SIDORYK K,JAROMIN A,FILIPCZAK N,et al. Synthesis and antioxidant activity of caffeic acid derivatives[J]. Molecules,2018,23(9):2199. DOI:10.3390/molecules23092199.

SEO H Y,KIM M K,LEE S H,et al. Kahweol ameliorates the liver inflammation through the inhibition of NF-κB and STAT3 activation in primary kupffer cells and primary hepatocytes[J]. Nutrients,2018,10(7):863. DOI:10.3390/nu10070863.

BAJAJ J S,IDILMAN R,MABUDIAN L,et al. Diet affects gut microbiota and modulates hospitalization risk differentially in an international cirrhosis cohort[J]. Hepatology,2018,68(1):234-247. DOI:10.1002/hep.29791.

KENNEDY O J,RODERICK P,BUCHANAN R,et al. Coffee,including caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee,and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma:a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis[J]. BMJ Open,2017,7(5):e013739. DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013739.

TAMURA T,HISHIDA A,WAKAI. Coffee consumption and liver cancer risk in Japan:a meta-analysis of six prospective cohort studies[J]. Nagoya J Med Sci,2019,81(1):143-150. DOI:10.18999/nagjms.81.1.143.

TAMURA T,WADA K,KONISHI K,et al. Coffee,green tea,and caffeine intake and liver cancer risk:a prospective cohort study[J]. Nutr Cancer,2018,70(8):1210-1216. DOI:10.1080/01635581.2018.1512638.

VAN DAM R M,HU F B,WILLETT W C. Coffee,caffeine,and health[J]. N Engl J Med,2020,383(4):369-378. DOI:10.1056/NEJMra1816604.

WONGTRAKUL W,NILTWAT S,CHARATCHAROENWITTHAYA P. The effects of modest alcohol consumption on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease:a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Front Med,2021,8:744713. DOI:10.3389/fmed.2021.744713.

AJMERA V,BELT P,WILSON L A,et al. Among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease,modest alcohol use is associated with less improvement in histologic steatosis and steatohepatitis[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol,2018,16(9):1511-1520.e5. DOI:10.1016/j.cgh.2018.01.026.

ROERECKE M,VAFAEI A,HASAN O S M,et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of liver cirrhosis:a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Am J Gastroenterol,2019,114(10):1574-1586. DOI:10.14309/ajg.0000000000000340.

?BERG F,BYRNE C D,PIROLA C J,et al. Alcohol consumption and metabolic syndrome:clinical and epidemiological impact on liver disease[J]. J Hepatol,2023,78(1):191-206. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2022.08.030.

ALBILLOS A,GOTTARDI A D,RESCIGNO M. The gut-liver axis in liver disease:Pathophysiological basis for therapy[J]. J Hepatol,2020,72(3):558-577. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2019.10.003.

ZHANG D,HAO X X,XU L L,et al. Intestinal flora imbalance promotes alcohol-induced liver fibrosis by the TGFβ/smad signaling pathway in mice[J]. Oncol Lett,2017,14(4):4511-4516. DOI:10.3892/ol.2017.6762.

CHEN Y W,ZHOU J H,WANG L. Role and mechanism of gut microbiota in human disease[J]. Front Cell Infect Microbiol,2021,11:625913. DOI:10.3389/fcimb.2021.625913.

WANG D Z,YAN S,YAN J,et al. Effects of triphenyl phosphate exposure during fetal development on obesity and metabolic dysfunctions in adult mice:impaired lipid metabolism and intestinal dysbiosis[J]. Environ Pollut,2019,246:630-638. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2018.12.053.

ZHU L X,BAKER R D,ZHU R X,et al. Gut microbiota produce alcohol and contribute to NAFLD[J]. Gut,2016,65(7):1232. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311571.

DE FARIA GHETTI F,OLIVEIRA D G,DE OLIVEIRA J M,

et al. Influence of gut microbiota on the development and progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis[J]. Eur J Nutr,2018,57(3):861-876. DOI:10.1007/s00394-017-1524-x.

FEDERICO A,DALLIO M,GODOS J,et al. Targeting gut-liver axis for the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis:translational and clinical evidence[J]. Transl Res,2016,167(1):116-124. DOI:10.1016/j.trsl.2015.08.002.

LI F X,YE J Z,SHAO C X,et al. Compositional alterations of gut microbiota in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients:a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Lipids Health Dis,2021,20(1):22. DOI:10.1186/s12944-021-01440-w.

OH T G,KIM S M,CAUSSY C,et al. A universal gut-microbiome-derived signature predicts cirrhosis[J]. Cell Metab,2020,32(5):901. DOI:10.1016/j.cmet.2020.10.015.

YUAN J,CHEN C,CUI J H,et al. Fatty liver disease caused by high-alcohol-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae[J]. Cell Metab,2019,30(6):1172. DOI:10.1016/j.cmet.2019.11.006.

HU H M,LIN A Z,KONG M W,et al. Intestinal microbiome and NAFLD:molecular insights and therapeutic perspectives[J]. J Gastroenterol,2020,55(2):142-158. DOI:10.1007/s00535-019-01649-8.

BOURSIER J,MUELLER O,BARRET M,et al. The severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with gut dysbiosis and shift in the metabolic function of the gut microbiota[J]. Hepatology,2016,63(3):764-775. DOI:10.1002/hep.28356.

NEWSOME P N,SASSO M,DEEKS J J,et al. FibroScan-AST(FAST)score for the non-invasive identification of patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis with significant activity and fibrosis:a prospective derivation and global validation study[J]. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol,2020,5(4):362-373. DOI:10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30383-8.

FANG J,YU C H,LI X J,et al. Gut dysbiosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease:pathogenesis,diagnosis,and therapeutic implications[J]. Front Cell Infect Microbiol,2022,12:997018. DOI:10.3389/fcimb.2022.997018.

REN R R,ZHENG Y. Sex differences in cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the US population[J]. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis,2023,33(7):1349-1357. DOI:10.1016/j.numecd.2023.03.003.

DISTEFANO J K. NAFLD and NASH in postmenopausal women:implications for diagnosis and treatment[J]. Endocrinology,2020,161(10):bqaa134. DOI:10.1210/endocr/bqaa134.

PALMISANO B T,ZHU L,STAFFORD J M. Role of estrogens in the regulation of liver lipid metabolism[J]. Adv Exp Med Biol,2017,1043:227-256. DOI:10.1007/978-3-319-70178-3_12.

JARUVONGVANICH V,SANGUANKEO A,RIANGWIWAT T,et al. Testosterone,sex hormone-binding globulin and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease:a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Ann Hepatol,2017,16(3):382-394. DOI:10.5604/16652681.1235481.

DONNELLY M C,STABLEFORTH W,KRAG A,et al. The negative bidirectional interaction between climate change and the prevalence and care of liver disease:a joint BSG,BASL,EASL,and AASLD commentary[J]. J Hepatol,2022,76(5):995-1000. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2022.02.012.

LI W,XIAO H T,WU H,et al. Analysis of environmental chemical mixtures and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease:NHANES 1999-2014[J]. Environ Pollut,2022,311:119915. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2022.119915.

KANAZAWA S. Does global warming contribute to the obesity epidemic?[J]. Environ Res,2020,182:108962. DOI:10.1016/j.envres.2019.108962.

HADLEY K,WHEAT S,ROGERS H H,et al. Mechanisms underlying food insecurity in the aftermath of climate-related shocks:a systematic review[J]. Lancet Planet Health,2023,7(3):e242-250. DOI:10.1016/S2542-5196(23)00003-7.

CANO R,P?REZ J L,D?VILA L A,et al. Role of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease:a comprehensive review[J]. Int J Mol Sci,2021,22(9):4807. DOI:10.3390/ijms22094807.

ZHANG X Y,ZHAO L G,DUCATMAN A,et al. Association of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance exposure with fatty liver disease risk in US adults[J]. JHEP Rep,2023,5(5):100694. DOI:10.1016/j.jhepr.2023.100694.

AN S J,YANG E J,OH S,et al. The association between urinary bisphenol A levels and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Korean adults:Korean National Environmental Health Survey(KoNEHS)2015-2017[J]. Environ Health Prev Med,2021,26(1):91. DOI:10.1186/s12199-021-01010-7.

FLING R R,ZACHAREWSKI T R. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor

(AhR)activation by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo- p-dioxin

(TCDD)dose-dependently shifts the gut microbiome consistent with the progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease[J]. Int J Mol Sci,2021,22(22):12431. DOI:10.3390/ijms222212431.

ZHU X Y,XIA H G,WANG Z H,et al. In vitro and in vivo approaches for identifying the role of aryl hydrocarbon receptor in the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease[J]. Toxicol Lett,2020,319:85-94. DOI:10.1016/j.toxlet.2019.10.010.

KIM K,MELOUGH M M,VANCE T M,et al. Dietary cadmium intake and sources in the US[J]. Nutrients,2018,11(1):2. DOI:10.3390/nu11010002.

LI Y X,CHEN C,LU L P,et al. Cadmium exposure in young adulthood is associated with risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in midlife[J]. Dig Dis Sci,2022,67(2):689-696. DOI:10.1007/s10620-021-06869-8.

PARK E,KIM J,KIM B,et al. Association between environmental exposure to cadmium and risk of suspected non-alcoholic fatty liver disease[J]. Chemosphere,2021,266:128947. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128947.

CAVE M,APPANA S,PATEL M,et al. Polychlorinated biphenyls,lead,and mercury are associated with liver disease in American adults:NHANES 2003-2004[J]. Environ Health Perspect,2010,118(12):1735-1742. DOI:10.1289/ehp.1002720.

FREDIANI J K,NAIOTI E A,VOS M B,et al. Arsenic exposure and risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease(NAFLD)among U.S. adolescents and adults:an association modified by race/ethnicity,NHANES 2005-2014[J]. Environ Health,2018,17(1):6. DOI:10.1186/s12940-017-0350-1.

YANG C Y,LI Y Y,DING R,et al. Lead exposure as a causative factor for metabolic associated fatty liver disease(MAFLD)and a lead exposure related nomogram for MAFLD prevalence[J]. Front Public Health,2022,10:1000403. DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2022.1000403.

YOUNG J L,CAVE M C,XU Q,et al. Whole life exposure to low dose cadmium alters diet-induced NAFLD[J]. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol,2022,436:115855. DOI:10.1016/j.taap.2021.115855.

GU J,KONG A Q,GUO C Z,et al. Cadmium perturbed lipid profile and induced liver dysfunction in mice through phosphatidylcholine remodeling and promoting arachidonic acid synthesis and metabolism[J]. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf,2022,247:114254. DOI:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.114254.

QIU T M,PEI P,YAO X F,et al. Taurine attenuates arsenic-induced pyroptosis and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis by inhibiting the autophagic-inflammasomal pathway[J]. Cell Death Dis,2018,9(10):946. DOI:10.1038/s41419-018-1004-0.

CHEN H G,ZHU C X,ZHOU X. Effects of lead and cadmium combined heavy metals on liver function and lipid metabolism in mice[J]. Biol Trace Elem Res,2023,201(6):2864-2876. DOI:10.1007/s12011-022-03390-5.

AUGUET T,BERTRAN L,BARRIENTOS-RIOSALIDO A,

et al. Are ingested or inhaled microplastics involved in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease?[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health,2022,

19(20):13495. DOI:10.3390/ijerph192013495.

LI L,XU M J,HE C,et al. Polystyrene nanoplastics potentiate the development of hepatic fibrosis in high fat diet fed mice[J]. Environ Toxicol,2022,37(2):362-372. DOI:10.1002/tox.23404.

YIN J L,JU Y,QIAN H H,et al. Nanoplastics and microplastics may be damaging our livers[J]. Toxics,2022,10(10):586. DOI:10.3390/toxics10100586.

YEE M S,HII L W,LOOI C K,et al. Impact of microplastics and nanoplastics on human health[J]. Nanomaterials,2021,11(2):496. DOI:10.3390/nano11020496.

CHENG W,LI X L,ZHOU Y,et al. Polystyrene microplastics induce hepatotoxicity and disrupt lipid metabolism in the liver organoids[J]. Sci Total Environ,2022,806(Pt 1):150328. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150328.

LAI W C,XU D,LI J M,et al. Dietary polystyrene nanoplastics exposure alters liver lipid metabolism and muscle nutritional quality in carnivorous marine fish large yellow croaker(Larimichthys crocea)[J]. J Hazard Mater,2021,419:126454. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126454.

THANGAVEL P,PARK D,LEE Y C. Recent insights into particulate matter(PM2.5)-mediated toxicity in humans:an overview[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health,2022,19(12):7511. DOI:10.3390/ijerph19127511.

SUN S Z,YANG Q Q,ZHOU Q X,et al. Long-term exposure to fine particulate matter and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease:a prospective cohort study[J]. Gut,2022,71(2):443-445. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2021-324364.

XU J X,ZHANG W,LU Z B,et al. Airborne PM2.5-induced hepatic insulin resistance by Nrf2/JNK-mediated signaling pathway[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health,2017,14(7):787. DOI:10.3390/ijerph14070787.

XU Z J,SHI L M,LI D C,et al. Real ambient particulate matter-induced lipid metabolism disorder:roles of peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor alpha[J]. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf,2022,231:113173. DOI:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.113173.

XU X H,LIU C Q,XU Z B,et al. Long-term exposure to ambient fine particulate pollution induces insulin resistance and mitochondrial alteration in adipose tissue[J]. Toxicol Sci,2011,124(1):88-98. DOI:10.1093/toxsci/kfr211.

FERRO D,BARATTA F,PASTORI D,et al. New insights into the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease:gut-derived lipopolysaccharides and oxidative stress[J]. Nutrients,2020,12(9):2762. DOI:10.3390/nu12092762.

LONG M H,ZHANG C,XU D Q,et al. PM2.5 aggravates diabetes via the systemically activated IL-6-mediated STAT3/SOCS3 pathway in rats' liver[J]. Environ Pollut,2020,256:113342. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113342.

LI R,SUN Q,LAM S M,et al. Sex-dependent effects of ambient PM2.5 pollution on insulin sensitivity and hepatic lipid metabolism in mice[J]. Part Fibre Toxicol,2020,17(1):14. DOI:10.1186/s12989-020-00343-5.

(收稿日期:2023-12-03;修回日期:2024-02-21)

(本文编辑:贾萌萌)