Etiology and management of urethral calculi:A systematic review of contemporary series

2024-02-25AndrewMortonArsalanTariqNigelDunglisonRahelEslerMatthewRoberts

Andrew Morton,Arsalan Tariq,Nigel Dunglison,Rahel Esler,Matthew J.Roberts,d,*

a Faculty of Medicine,The University of Queensland,Brisbane,Queensland,Australia

b Department of Urology,Ipswich Hospital,Queensland,Australia

c Department of Urology,Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital,Queensland,Australia

d The University of Queensland Centre for Clinical Research,Herston,Australia

KEYWORDS Urinary calculi;Urethra;Urethral calculi;Management algorithm

Abstract Objective: To conduct a systematic literature review on urethral calculi in a contemporary cohort describing etiology,investigation,and management patterns.Methods: A systematic search of MEDLINE and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials(CENTRAL) databases was performed.Articles,including case reports and case series on urethral calculi published between January 2000 and December 2019,were included.Full-text manuscripts were reviewed for clinical parameters including symptomatology,etiology,medical history,investigations,treatment,and outcomes.Data were collated and analyzed with univariate methods.Results: Seventy-four publications met inclusion criteria,reporting on 95 cases.Voiding symptoms (41.1%),pain(40.0%),and acute urinary retention (32.6%)were common presenting features.Urethral calculi were most often initially investigated using plain X-ray (63.2%),with almost all radio-opaque (98.3%).Urethral calculi were frequently associated with coexistent bladder or upper urinary tract calculi (16.8%) and underlying urethral pathology (53.7%)including diverticulum (33.7%) or stricture (13.7%).Urethral calculi were most commonly managed with external urethrolithotomy (31.6%),retrograde manipulation (22.1%),and endoscopic in situ lithotripsy (17.9%).Conclusion: This unique systematic review of urethral calculi provided a summary of clinical features and treatment trends with a suggested treatment algorithm.Management in contemporary urological practice should be according to calculus size,shape,anatomical location,and presence of urethral pathology.

1.Introduction

Urethral calculi are rare,and represent less than 1% of all urinary tract stones [1];therefore,available evidence is mostly limited to case reports and small series.Urethral calculi may arisede novoproximal to a urethral obstruction or within a diverticulum,and are often associated with a history of previous urethral surgery,recurrent urinary infection,and stasis [2,3].Alternatively,calculi can migrate from the bladder or upper urinary tract to obstruct the urethra,and rarely urethral steinstrasse can result as a complication following stone fragmentation procedures [4,5].

Urethral calculi variably present with nonspecific symptoms of pain (penile,perineal,suprapubic,and urethral),voiding difficulty,or acute urinary retention [6,7].Investigation is often initial plain imaging followed by selective use of urethrography and cystourethroscopy to confirm the diagnosis and determine underlying urethral abnormalities.Ultrasound may assist if radiolucent calculi are suspected and to evaluate the upper urinary tract due to high incidence of concomitant bladder and upper urinary tract calculi[7].Management of urethral calculi is variable and dependent on size,position,and other clinical(urinary retention and sepsis) and institutional (available technology) factors.Delay in diagnosis can occur and lead to significant morbidity including post-obstructive renal failure,urethral injury,urethrocutaneous fistula,incontinence,and impotence.

Available evidence in the literature is lacking due to an absence of any large cohort or prospective studies.With technological advancements and the increase in use of endoscopic techniques,the management patterns in urethral calculi are likely to have changed,which are yet to be reviewed.Therefore,the aim of this study was to systematically review contemporary published literature related to urethral calculi to describe etiology and treatment patterns.

2.Materials and methods

2.1.Search strategy

A systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines [8].The published study protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020162683) including performed search strategy and can be accessed online [9].The MEDLINE and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) databases were queried in December 2019 for studies published in the English-language between January 2000 and December 2019.The medical subject heading (MeSH) search terms “urethra”,“calculi”,“lithiasis”,“urolithiasis”,and “calcification” combined with the text-word search “steinstrasse” were used to extract relevant studies.In addition,reference lists of included studies were examined for further relevant studies.Study titles,abstracts,and full-texts were reviewed independently by two different authors(Morton A and Tariq A).Any discrepancy in included studies between reviewers was discussed and resolved by consensus.

2.2.Eligibility criteria

All articles including case reports and case series on urethral calculi were considered and included if published between January 2000 and December 2019 with full-text availability,in the English-language,and reported on raw data describing symptomology,investigations,and management.Review studies,conference abstracts,unpublished studies,short reports,editorials,and gray literature were excluded.

2.3.Outcomes and data management

Data were extracted independently by two authors (Morton A and Tariq A) into Microsoft Excel (Microsoft,Seattle,WA,USA).Extracted data included patient demographics (age and sex),geographic location,medical history,symptomatology,physical examination and laboratory findings,imaging modality utilized,initial and definitive management,stone characteristics (location,composition,and size),length of stay,follow-up,and clinical outcomes.

2.4.Quality assessment

A critical appraisal tool was used for quality assessment of included articles [10,11]as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook[12].It contains an eight-point checklist regarding the availability of relevant information reported within each study.Quality assessment was performed for all included articles concurrently during data collection by one author(Morton A) with a random sample cross-checked by another author (Tariq A).Overall,quality of studies was fair,with most (91.9%) reporting a clear description of patient demographics,clinical history,physical examination findings,diagnostic investigations,treatment,and short-term outcome.Calculus characteristics including size and composition were reported in 89.2% and 41.9% of studies,respectively.Adequate descriptions of length of hospital stay and clinical condition at long-term follow-up were reported suboptimally,in only 32.4% and 55.4% of studies,respectively.

2.5.Statistical methods

Data synthesis was performed using categorical and continuous variables including age,gender,symptomatology,etiology,investigations,management,and length of hospital stay.Descriptive statistics (mean,median,standard deviation,and interquartile ranges) for continuous variables and frequencies and percentage distribution for categorical variables were calculated.Hypothesis testing was conducted using two-tailedt-test and Fisher’s exact test (p-value of <0.05 was considered to be significant)using GraphPad QuickCalcs(GraphPad Software,Inc.,Boston,MA,USA,available from https://graphpad.com/quickcalcs/).

3.Results

3.1.Study selection

The search strategy identified a total of 1364 database entries,of which 1249 were excluded by title and abstract evaluation (Fig.1).Full-text articles (n=115) were assessed for eligibility according to the pre-identified inclusion and exclusion criteria (Fig.1).Overall,74 studies(71 case reports and three case series) reporting on a total of 95 patients were included.Most cases originated from Asia(67%),including the Middle East(24%),East Asia(22%),Indian Subcontinent (20%),and South-East Asia (1%).Cases also originated from Europe (12%),Africa (9%),North America (6%),Australia (3%),and South America (2%).

3.2.Patient demographics

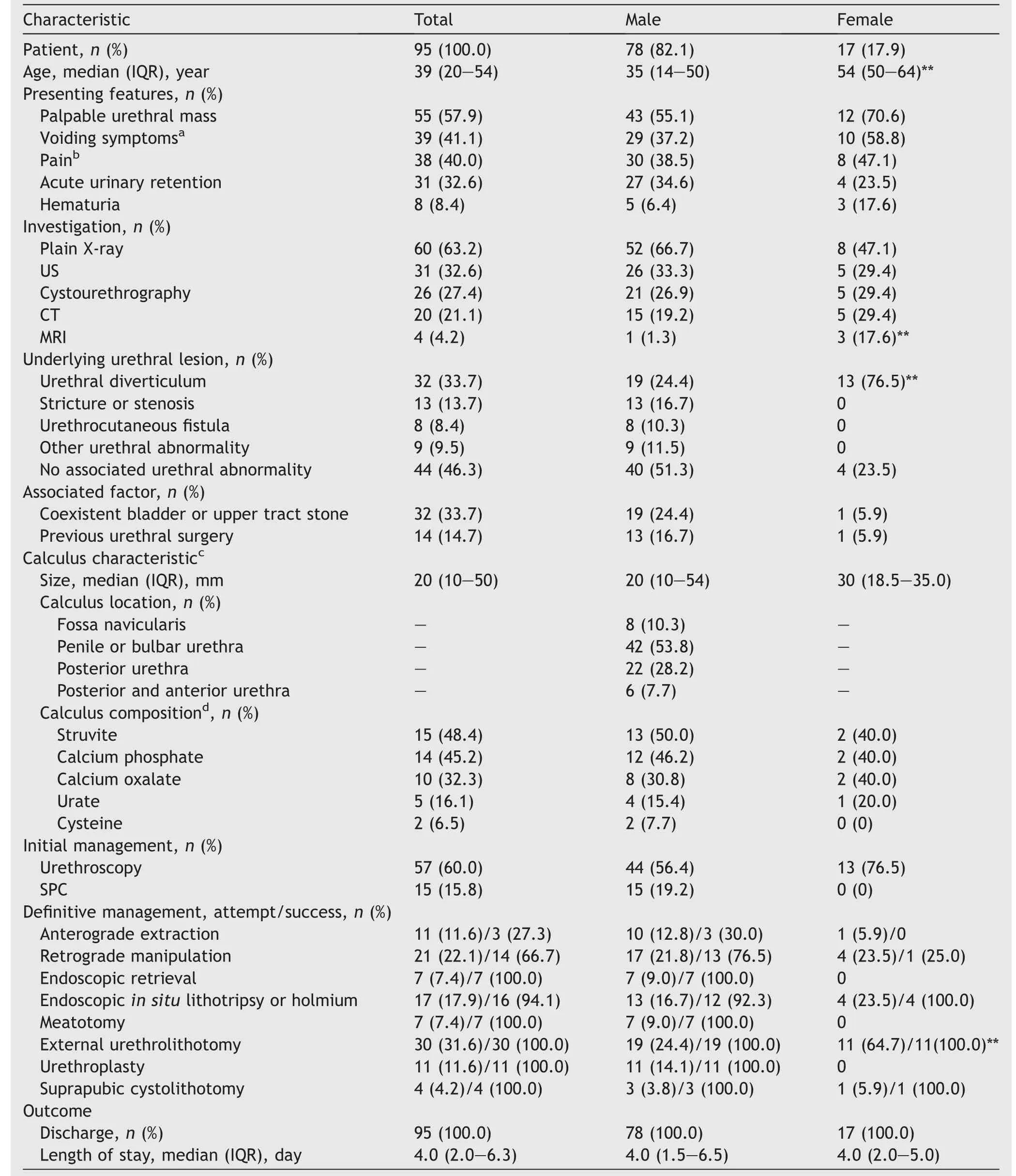

Of the 95 identified patients,most were male (82.1%;Table 1)aged between 10 months old and 82 years old,with 22 patients (23.2%) being children (<16 years old).

Table 1 Summary of published cases on urethral calculi in a contemporary series according to sex.

3.3.Symptoms and investigations

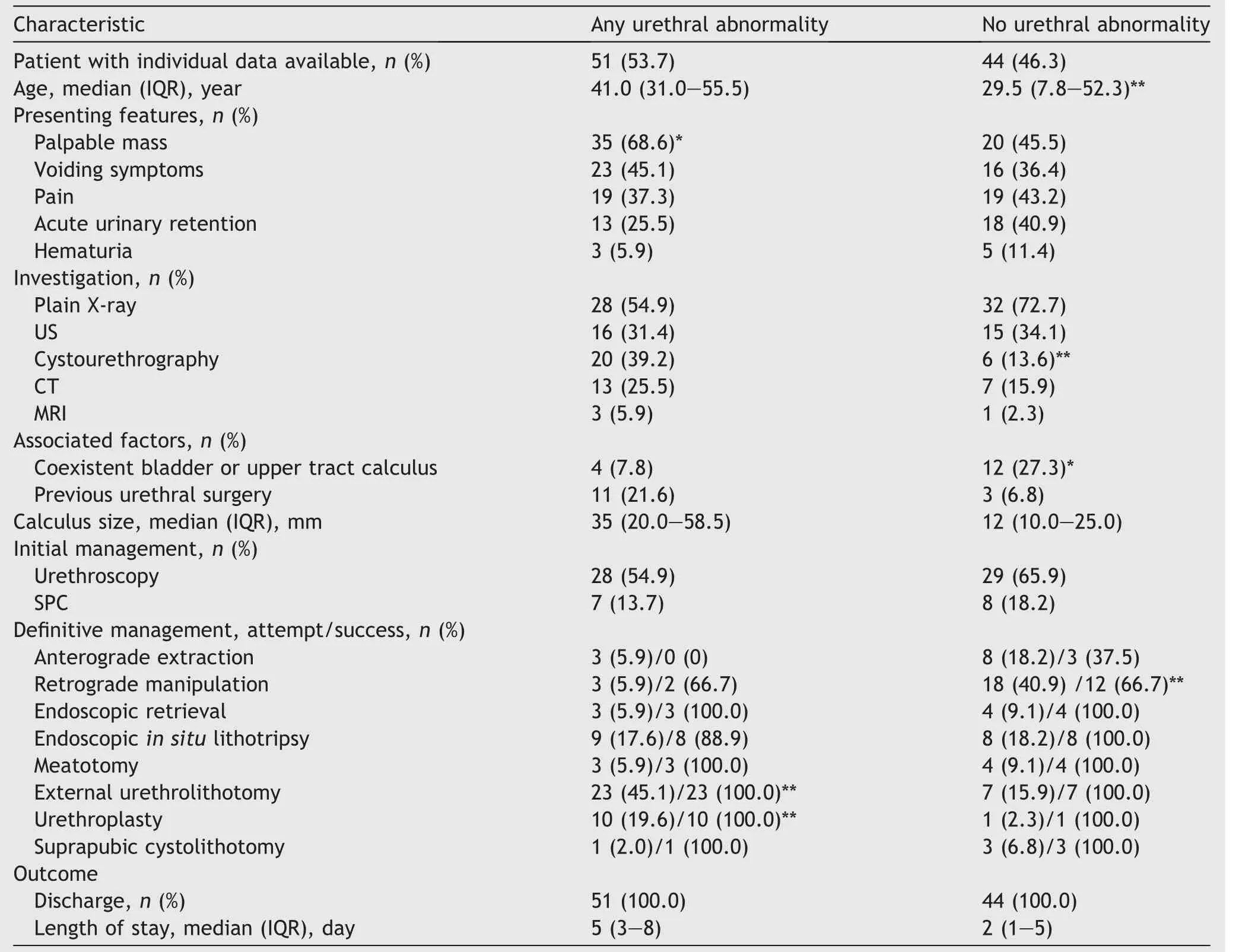

The most common clinical features reported were a palpable urethral mass (57.9%),voiding symptoms including weak stream,dysuria,or post-void dribbling (41.1%),pain including penile,perineal,or suprapubic (40.0%),and acute urinary retention (32.6%).Patients were significantly more likely to present with a palpable urethral mass in the presence of underlying urethral pathology (p<0.05;Table 2) or calculi located within the penile or bulbar urethra(p<0.001;Table 3).No significant differences in presenting features were demonstrated according to gender.

Table 2 Summary of published cases on urethral calculi in a contemporary series according to presence of any underlying pathology.

Imaging most commonly reported was plain X-ray(63.2%),ultrasound (32.6%),cystourethrography (27.4%),and computed tomography (21.1%).Urethral calculi were almost always radio-opaque (59/60 patients;98.3%).Cystourethrography was utilized more commonly in patients with previously known urethral abnormality,compared with patients who had no previous or suspected urethral pathology (39.2%vs.13.6%;p=0.006).No differences in imaging modality utilization were demonstrated according to calculus location.MRI (4.2%) was infrequently used overall but more commonly performed in females(p=0.02).Of the four patients who underwent MRI,three were in female patients,and three in patients with calculi associated with a urethral diverticulum.MRI was generally performed after calculus identification on plain imaging or ultrasound,to further define anatomy and extent of the calculus prior to operative intervention.

3.4.Etiology and associated factors

Overall,any associated lower urinary tract pathology was present in 51 (53.7%) patients,including urethral diverticulum (33.7%),urethral stricture (13.7%),and urethrocutaneous fistula (8.4%).Calculi associated with diverticula were more common in females than males(76.5%vs.24.4%;p<0.001).A small number of cases were associated with a history of urethral hairball (n=5,5.3%),megalourethra (n=2,2.1%),urethral foreign body (n=1,1.1%),and posterior urethral valve (n=1,1.1%).Patients with any underlying urethral pathology more commonly encountered urethral calculi within the penile or bulbar urethra (76.3%vs.32.5%;p=0.01),whereas patients with normal urethras more commonly encountered calculi within the posterior urethra (45.0%vs.10.5%;p<0.001).Some patients also had a history of previous urethral surgery (14.7%) or coexistent bladder or upper urinary tract calculi (16.8%).

3.5.Calculus characteristics

Calculus analysis most commonly demonstrated struvite(48.4%),followed by calcium phosphate (45.2%) and calcium oxalate (32.3%).In males,calculi were most commonly located in the penile or bulbar urethra (53.8%),and posterior urethra (28.2%),with a minority residing within the fossa navicularis (10.3%).Median calculus sizes(largest diameter of the largest calculus if multiple present)were 20 mm(all patients),20 mm(males),and 30 mm(females).There was a trend towards larger median calculus size in patients with any urethral pathology (35 mmvs.12 mm;p=0.08).

3.6.Initial management

Most patients underwent urethroscopy (n=57;60%).Overall,a suprapubic urinary catheter was placed in 15 (15.8%)males,and 0 female.

3.7.Non-operative management

Two patients (2.1%) had spontaneous passage of urethral calculi without any intervention,with one patient having multiple calculus fragments (steinstrasse) within the anterior and posterior urethra,whilst the other patient had a 20 mm calculus within the fossa navicularis.Both cases had no associated lower urinary tract disease.Three out of 11 patients underwent successful non-operative anterograde extraction with forceps under direct vision,manual manipulation and expulsion of stone.

3.8.Manual manipulation and expulsion of stone

Meatotomy was performed in 7 (7.4%) patients for calculi located in the fossa navicularis.Retropulsion of calculi toward the bladder (with either urinary catheter or cystoscope) was successful in 14 of 21 cases,with a significantly greater proportion of these in posterior urethral calculi(p<0.001) and patients with no urethral pathology(p=0.003).Subsequent endoscopic intravesical calculus fragmentation was the most common definitive treatment(9/14 patients;64.3%) followed by transvesical extraction(percutaneous or open cystolithotomy;5/14 patients;35.7%).Insitu disintegration with lithotripsy or holmium laser was successfully performed in 16 of 17 patients,and endoscopic retrieval in 7 of 7 patients.

Open surgery including external urethrolithotomy was performed in 30 (31.6%) patients,and was significantly more common for calculi located within the penile or bulbar urethra (p=0.003),in patients with any urethral pathology(45.1%vs.15.9%;p<0.01),and in females(64.7%vs.24.4%;p<0.01),presumably due to high observed incidence of calculi associated with a urethral diverticulum in females.Urethroplasty was performed in 11 (11.6%) cases,mostly due to concurrent urethral pathology (19.6%vs.2.3%;p<0.01).Extraction of urethral calculi through a transvesical approach with open cystolithotomy was uncommon (2.0%).

Management of urethral calculi over time according to broad categories demonstrated an increase in the proportion of utilization of endoscopic methods (endoscopic retrieval,in situlithotripsy or lasertripsy,and retrograde manipulation followed by subsequent intravesical fragmentation)from 22.2% in 2000-2004 to 44.0% in 2015-2020(Supplementary Fig.1).Across the same period,there was a corresponding decline in the utilization of open surgical approaches(66.7%vs.56.0%)and non-operative approaches(11.1%vs.0%).Management according to urethral calculus size suggested that calculi less than 20 mm were significantly more likely to be amenable to successful retrograde manipulation compared with calculi measuring 20 mm or greater (34.5%vs.5.4%;p=0.003).In contrast,larger calculi(diameter ≥20 mm)more frequently required an open surgical approach in the form of urethrolithotomy(43.2%vs.10.3%;p=0.003).

3.9.Outcomes

Median patient length of stay in hospital was 4.0 days(interquartile range 2.0-6.3 days).Median hospital stay according to broad treatment category in non-operative(1.0 day) was the shortest,followed by endoscopic(2.0 days),and open (6.5 days).No deaths were reported,with all patients successfully discharged from hospital following treatment.Patient follow-up was reported in 41.1% of cases,with a total of 5 (5.3%) complications including development of urethral stricture (n=3),urinary incontinence (n=1),and bladder calculus (n=1).Of the cases who developed urethral stricture at follow-up,one was attributed to unsuccessful traumatic attempts to milk the anterior urethral calculus distally.

4.Discussion

This systematic review of published case reports and case series,to our knowledge,represents the largest summary of available literature regarding etiology and management of urethral calculi.Acute urinary retention,voiding symptoms,pain,and a palpable mass were common presenting features and,in most cases,investigated with plain imaging and urethroscopy.Urethral calculi are commonly associated with urethral pathology and coexistent bladder or upper tract calculi.Overall,management favored less invasive techniques with retrograde manipulation andin situlithotripsy most commonly performed followed by maximally invasive open approaches (external urethrolithotomy and urethroplasty).Further,our study supports the traditional recommendation that management is dependent on calculus size,location,and presence of associated urethral pathology.Urethral calculi have a broad range of treatment options.Uncomplicated and distal urethral calculi may be amenable to extraction with non-operative measures including forceps,or instillation of 2% lidocaine gel followed by spontaneous expulsion as previously described[13].Posterior urethral calculi that are not impacted or associated with urethral obstruction may be pushed back into the bladder with retrograde manipulation and subsequent intravesical fragmentation or suprapubic extraction [14].Alternatively,urethral calculi may be retrieved endoscopically or fragmentedin situwith lithotripsy or holmium lasertripsy [15].Whilst these non-operative and minimally invasive endoscopic methods are preferable,open surgical approaches including urethrolithotomy,urethroplasty,or cystolithotomy may still be indicated for large and impacted calculi,or those with associated pathology (diverticulum,stricture,and urethrocutaneous fistula) requiring simultaneous treatment.

Overall management of urethral calculi in contemporary practice has shifted towards an increased utilization of endoscopic methods over time,with the proportion of calculi successfully managed endoscopically increasing from 2000-2004 to 2015-2020 (22.2%vs.44.0%;Supplementary Fig.1).This is likely due to the significant advances in endoscopic technology over the past few decades and its growing utilization in urolithiasis management as observed in several different health environments globally [16,17].Additionally,endoscopic techniques for urethral calculi represent a less invasive and effective alternative to traditional open surgical management.Specifically,in situcalculus fragmentation with electrohydraulic and ultrasonic lithotripsy,as well as holmium laser lithotripsy has demonstrated good safety and effectiveness,including large and impacted calculi that are not amenable to retrograde manipulation [15,18,19].Initial retrograde manipulation is most commonly recommended as the treatment option of choice in urethral calculi that are not impacted,spiked,or associated with urethral pathology[6,7].Its utilization in previous reports varies considerably between 22.1% and 72.2% [3,7,18,20,21],with the number of required attempts and success rate of retrograde manipulation not well documented in the literature.In this study,retrograde manipulation was a commonly attempted procedure in 22.1% of cases with reported success in 66.7% of cases,similar to previous studies (66% and 86%,respectively) [6,22].Here,non-operative measures including lidocaine gel instillation had a relatively low success rate(27.3%),which is consistent with the study (13%) by Kamal and colleagues [6],but in contrast to the research that el-Sherif and el-Hafi [13]demonstrated successful calculus expulsion in 14 of 18 patients (77.8%).This discrepancy is likely due to stricter patient selection criteria that only included patients with urethral calculi less than 10 mm in diameter and who had no history of urethral disease.Supplementary Fig.2 outlines a recommended algorithm in the treatment of urethral calculi.

Regarding the clinical features and investigation of urethral calculi,there is considerable heterogeneity amongst historical reports.We found that patients relatively infrequently presented with acute urinary retention (32.6%),which is consistent with several previous studies reporting prevalence between 2% and 22%;however,other studies reported high prevalence between 78% and 89% [3,6,7,20].Similarly,a palpable urethral mass was an uncommon finding in prior reports between 4% and 8%;however,we demonstrated presence of a palpable mass in 57.9% of cases which emphasizes the importance of thorough genitoscrotal and pelvic examination in the workup of suspected patients.Plain imaging is usually sufficient to confirm the diagnosis,as we demonstrated that urethral calculi were radio-opaque in 98.3% of cases,which is similar to a recent case series of 54 patients showing 98% [6].However,this is in disagreement with earlier reports that only achieved a diagnosis on plain imaging in 43% of cases,which was attributed to inadequate imaging technique that did not extend caudally enough to include the urethra,or different calculus compositions consisting of a greater proportion of radiolucent calculi [3].We found ultrasound to be a commonly performed imaging investigation in 32.6% of cases.It is useful in imaging the urethra where radiolucent calculi are suspected,but we also emphasize its importance in evaluating the bladder and upper urinary tracts as we demonstrated an incidence of coexistent calculi of 16.8% which is similar to previous reports between 32% and 33% [7,21].Additionally,it is strongly recommended that clinicians perform a careful and thorough evaluation to exclude underlying urethral pathology given its high prevalence(53.7%) among patients in this cohort.This should occur even in cases of urethral calculi that are successfully managed conservatively.Interestingly,in the 17 female cases included within this study,there was a high proportion of calculi associated with a urethral diverticulum (13/17 cases;76.5%).Urethral diverticula are thought to occur more commonly in females than males,with an incidence between 1.4% and 5.0% [23].Presence of calculi within a diverticulum reportedly occurs between 1% and 10% of the time,with stone formation resulting from chronic urinary stasis and infection [24].Urethral diverticula typically present with non-specific symptoms,and can be investigated with urethrography,transvaginal ultrasound,or urethroscopy;however,previous studies have demonstrated poor performance of ultrasound in adequately delineating the diverticular ostium and surrounding anatomy[25].Similarly,urethroscopy previously only identified the ostium in 23% of cases,though useful in excluding other urethral pathology.Where available,MRI should be considered in these cases to aid diagnosis and surgical treatment planning [25].

Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that geographic distribution and chemical composition of urolithiasis are influenced by several factors including racial distribution,socioeconomic status,hygiene,and dietary factors including protein intake[26-28].Upper urinary tract calculi are more commonly composed of calcium oxalate and phosphate and are more prevalent in economically developed countries,whereas lower tract calculi composed of calcium oxalate,urate,and ammonium are widespread across Asia[26].This is consistent with the present findings,which found cases of urethral calculi most commonly originated from Asia (67%),with few reports from Europe (12%)and North America(6%).Another interesting finding was the relatively high proportion of pediatric urethral calculi cases in this cohort (22/95 patients;23.2%).Many of these cases were found to be predisposed by underlying urethral abnormalities including congenital malformations or a history associated corrective surgeries that may have involved techniques with a high risk of diverticulization or inclusion of hair-bearing skin.Other case series of urethral calculi have also reported relatively high proportions of pediatric cases including smaller cohorts from Sudan (8/36 patients;22.2%)and Kuwait(12/86 patients;14.0%),but in contrast to a cohort from Saudi Arabia (1/51 patients;2.0%) [7,20,21].Although the prevalence of pediatric urolithiasis is generally rare,representing only 2%-3% of all stone-formers,this again varies according to region with several developing countries across the Middle East and Asia recognized for high incidences of pediatric urolithiasis [26,29].

Since this study is a systematic review including case reports and case series,our findings and conclusion are limited by the quality and detail of data reported.Unfortunately,there is likely to be inconsistent reporting between cases and inherent publication bias that may favor cases with more interesting or extreme pathologies or management strategies.Despite this,the authors believe that this represents the most comprehensive summary of all contemporary urethral calculi-related data.Given the limited number of case reports and case series available in the literature,we performed basic descriptive statistical analysis only.

Conclusion

Urethral calculi are a rare clinical entity and often present with non-specific symptoms.Plain imaging is usually sufficient to make the diagnosis.Treatment choice should take into consideration the urethral calculus size,location,and presence of any underlying urethral pathology,with retrograde manipulation and less invasive endoscopic techniques initially preferred to open surgery.

Author contributions

Study concept and design: Andrew Morton,Matthew J.Roberts.

Data acquisition: Andrew Morton,Arsalan Tariq.

Data analysis: Andrew Morton,Arsalan Tariq.

Drafting of manuscript: Andrew Morton,Arsalan Tariq,Nigel Dunglison,Rachel Esler,Matthew J.Roberts.

Critical revision of the manuscript:Andrew Morton,Arsalan Tariq,Nigel Dunglison,Rachel Esler,Matthew J.Roberts.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A.Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajur.2021.12.011.

杂志排行

Asian Journal of Urology的其它文章

- Transurethral resection of bladder tumor:A systematic review of simulator-based training courses and curricula

- Oncologic outcomes with and without amniotic membranes in robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy: A propensity score matched analysis

- Single nucleotide polymorphism within chromosome 8q24 is associated with prostate cancer development in Saudi Arabia

- The risk of prostate cancer on incidental finding of an avid prostate uptake on 2-deoxy-2-[ 18F]fluoro-D-glucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography for non-prostate cancer-related pathology:A single centre retrospective study

- Prevention of thromboembolic events after radical prostatectomy in patients with hereditary thrombophilia due to a factor V Leiden mutation by multidisciplinary coagulation management

- Transurethral prostate surgery in prostate cancer patients: A population-based comparative analysis of complication and mortality rates