Genetic variation of sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) in Gampaha and Kurunegala districts of Sri Lanka: Complementing the morphological identification

2022-08-26TharakaWijerathnaNayanaGunathilakaWasanaRodrigo

Tharaka Wijerathna, Nayana Gunathilaka✉, Wasana Rodrigo

1Department of Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya, Ragama, Sri Lanka

2Department of Zoology, Faculty of Natural Sciences, The Open University of Sri Lanka, Nawala, Nugegoda, Sri Lanka

ABSTRACT

KEYWORDS: Morphology; Sand fly; Identification; Barcoding;Sequencing

1. Introduction

Phlebotomine sand flies are of significant public health importance, especially in tropical areas of the world due to the transmission of leishmaniasis[1]. The global sand fly fauna consists of over 800 species classified under five major genera: Phlebotomus,Sergentomyia, Lutzomyia, Brumptomyia and Warileya[2]. However,some species in genera Phlebotomus and Lutzomyia have been experimentally confirmed as vectors for leishmaniasis transmission[2,3]. In Sri Lanka, 22 species of sand flies have been identified so far[4]. However, only Phlebotomus (P.) argentipes has been characterized as the vector for disease transmission[5,6].

Accurate identification of sand flies in a disease endemic area is one of the main aspects that need to be addressed when defining the potential risk for disease transmission. Although morphology and morphometry based taxonomical keys are more useful for field surveillance, this has several limitations since it needs recognition and analysis of many structures, primarily in the head and genitalia[7]. On the other hand, species identification is complicated since it entails considerable skill and taxonomic expertise. Further, deterioration of samples during the collection,transport, preservation or improper mounting techniques hinders the morphological confirmation of species. If the specimen is undescribed, morphological keys will be of little help in detecting that. However, in such situations, the most promising approach for identification is DNA barcoding[7]. The most commonly used method is the amplification and sequencing of the sand fly mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase subunit Ⅰ (COⅠ) gene,followed by the comparison with the NCBI database of known sequences[7].

Sri Lanka is a tropical island located in the Indian Ocean off the southern tip of the Indian peninsula. The island has an area of approximately 65 610 km2and has diverse habitats with a complex topography and variable rainfall patterns[8]. Sri Lanka is home to a rich diversity of fauna and flora with a high endemicity.Geographical separation and isolation of subpopulations can lead to speciation[9]. Distinct morphological characters can also evolve with time and such differentiation requires a long time since alterations in the morphological traits necessitate changes in multiple genes[10]. However, some genetically variant species could be at different geographical locations with similar morphological features. Therefore, confirmation of species identified by molecularbased approaches is of paramount importance in documenting the diversity of an organism. Despite the importance, the molecular characterization of sand flies is a poorly addressed area in Sri Lanka. Thus, the current study focused on the molecular level characterization and assessing the genetic diversity of phlebotomine sand flies in two endemic foci: Gampaha district and Kurunegala district in Sri Lanka.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethical approval

Ethical clearance for the present study was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee, Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka (Ref. No. P/204/12/2016).

2.2. Study areas

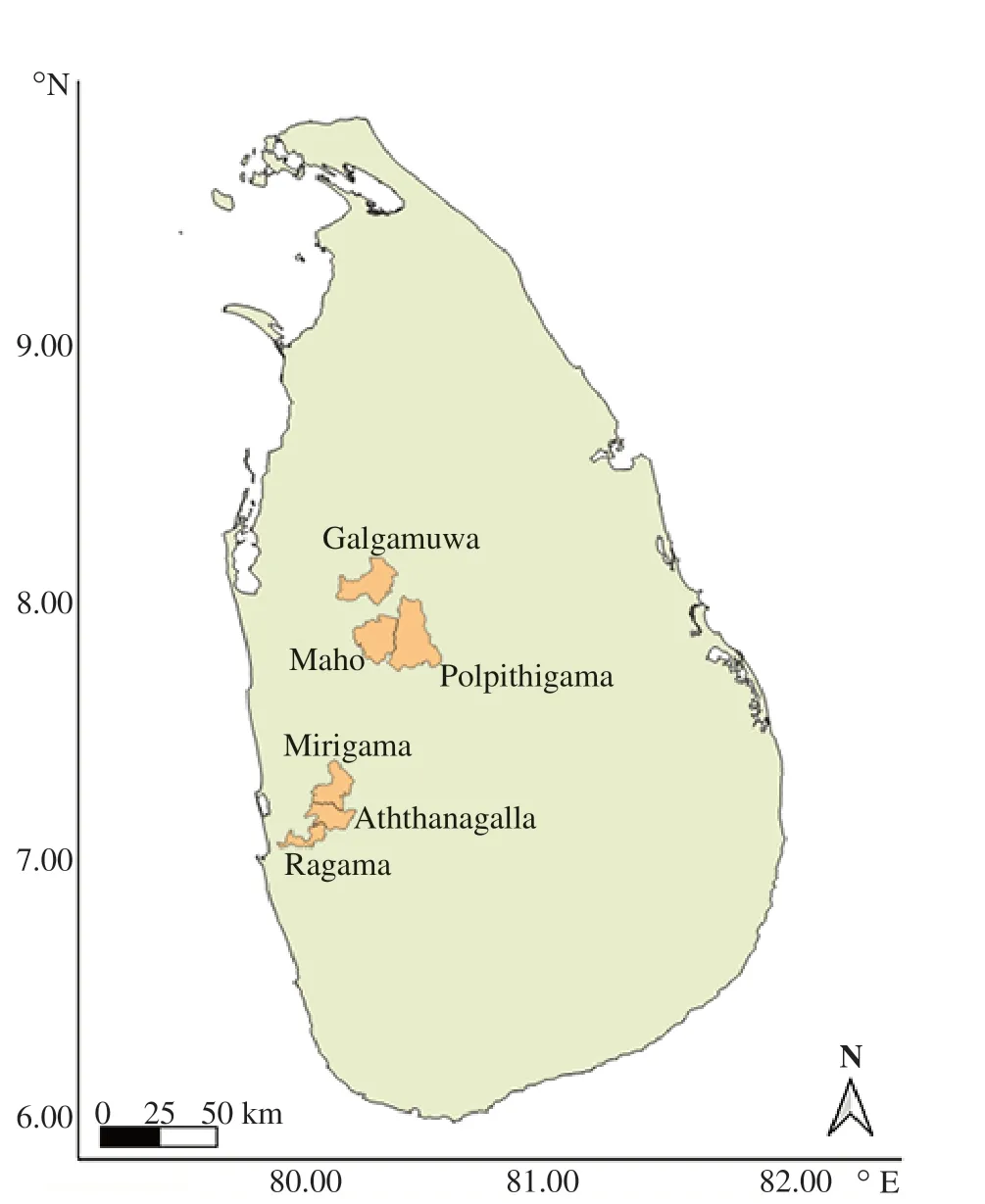

The Kurunegala district and Gampaha district showed a significant increase in leishmaniasis cases in the last five years[11]. Kurunegala district extends from the intermediate zone to the dry zone areas of Sri Lanka[12]. The average rainfall of the district ranged from 900 to 2 200 mm. The area receives rain from South Western (from May to August) and North Eastern Monsoons (October to January). The average annual temperature is 31.7 ℃, while the relative humidity ranges from 59% to 74% throughout the year, with a yearly average of 69.6%. The disease prevalence was considerably higher in some MOH areas, such as Polpithigama, Maho and Galamuwa MOH areas (Figure 1). These sites were selected for the field collection of sand flies.

Gampaha district is located in the wet zone of Sri Lanka[13].The mean annual rainfall stands at 1 423 mm with a mean annual temperature of 27.3 ℃ (22.7-34.3 ℃). This district is a new focus of leishmaniasis in Sri Lanka with a considerable increase in the patients during the last two years[14]. Therefore, considering the prevalence of disease incidence and occurrence of sand flies,Mirigama, Ragama and Aththanagalla MOH areas were selected for field surveillance (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Locations of the sand fly collection sites Sri Lanka.

2.3. Collection of sand flies

Field entomological surveillance was carried out monthly from May 2017 to December 2018. Sand flies were collected from selected localities in each district using four different field collection techniques: hand collection (HC), light traps (LT), sticky traps (ST)and cattle baited net trap (CBNT) according to the entomological field techniques specified by the World Health Organization[15].

2.4. Specimen processing and morphological identification

The specimens were dissected on a glass slide with sterile saline using sterile dissecting needles separating the head, wings and the distal end of the abdomen from the rest of the body. These parts were mounted in Hoyer’s medium and used for morphological identification. The remaining parts of the specimens, including the thorax with legs and proximal parts of the abdomen were transferred individually to sterilized 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes and used for DNA extraction.

Mounted sand fly specimens were examined using a dissecting microscope (Labomed CZM4 Binocular Zoom Microscope, Lobo American Inc, USA, 10×to 40×) and separated according to sex.Specimens were dissected on a glass slide with saline separating the terminal part of the abdomen, wings and the entire head using a fine needle and mounted with Hoyers medium for later identification.The sand flies were identified based on morphometric and meristic characters[16]. All morphometric measurements were taken using an ocular micrometre mounted to the binocular microscope. Ten groups of sand flies were selected depending on the species and locality of collection. This includes two species (S. punjabensis and P. argentipes) collected from all 3 sites of Kurunegala District (6 groups) and 2 species (Unidentified Sergentomyia sp. and S. babu insularis) from Mirigama (2 groups), one species from Ragama(1 group) and one species (Unidentified Sergentomyia sp.) from Aththanagalla (1 group). Three randomly chosen specimens (only 2 if not available) from each group were used for barcoding analysis.

2.5. DNA extraction

MightyPrep reagent for DNA (Takara Bio Inc, Japan) was used for DNA extraction according to the manufacturer’s guide with some minor modifications. A volume of 100 μL from MightlyPrep reagent was added into each microcentrifuge tube with the thorax and the proximal parts of the abdomen of the sand fly. The specimens were crushed individually using a sterile 200 μL pipette tip. New pipette tips were used every time to prevent cross-contamination. The samples were subjected to a hard vortex for 10 seconds, followed by incubation at 95 ℃ for 20 minutes. The lysates were allowed to cool down to room temperature and subjected to another hard vortex for 10 seconds. Finally, the DNA extracts were centrifuged at 8 000×g for 10 minutes and stored at −20 ℃ until use for the PCR assays.

2.6. Amplification of the genomic DNA of the field caught sand flies

The sand fly DNA was amplified using standard insect DNA barcoding primers LCO 1490 (Forward primer: 5′-GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3′) and HCO 2198(Reverse primer: 5′-AAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAATCA-3′)[17]targeting mitochondrial COⅠof the sand fly (at least 650 bp). The amplification was carried out using MightyAmp DNA polymerase version 3 kit (Takara, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions, subjected to minor modifications.

The reactions were carried out in a volume of 20 μL of the solution, with 1 μL of DNA extract as the template, 10 μL of MightyAmp Buffer V3 containing 4 mM MgCl2, dNTP (600 μM of each), 2 μL of 10× additives, 2 μL of Rediload dye (Invitrogen,USA), 0.12 μL of 50 μM of each primer (forward and reverse),0.4 μL of 2.5 U MightyAmp DNA polymerase and 4.36 μL of nuclease-free water.Amplification was performed in a thermal cycler (SimpliAmpTM,Applied Biosystems) programmed for an initial heating step at 98 ℃ for 2 minutes, 40 cycles of denaturation at 98 ℃ for 10 seconds, annealing at 55 ℃ for 15 seconds, extension at 68 ℃ for 40 seconds, and a final cooling step at 4 ℃ for 5 minutes.

2.7. Genomic DNA sequencing

The PCR amplicons were purified using QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) and those samples were sent to Macrogen,South Korea (Macrogen Inc., 1001, 254 Beotkkot-ro, Geumcheongu, Seoul, South Korea) for COⅠpartial gene sequencing with the same universal primers (LCO 1490 and HCO 2198) and sequenced using the Sanger method.

2.8. Nucleotide sequence analysis

The consensus sequences were generated for each specimen by editing the obtained chromatograms to remove overlapping peaks at the two ends using BioEdit 7.2 (Informer Technologies,Inc.). The DNA sequences were aligned with Clustal W tool[18]of Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis 10.0 (Pennsylvania State University)[19]. Each sequence was compared with other mitochondrial genomes using the BLAST (NCBI, USA) programme to confirm the species or genus level identity.

The DnaSP6 programme[20] was used to obtain descriptive information on the sequences, such as the number of polymorphic sites and haplotypes per species. The model suitable for the evolutionary relationship analysis was statistically selected using the maximum likelihood method in Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis 10.0. The lowest values of Bayesian Information Criterion and Akaike Information Criterion, corrected were observed for Tamura-Nei (TN93) model[21], incorporating the shape parameter of the gamma distribution (G=0.303 4). Intra and interspecies divergences of nucleotide sequence and composition were calculated using the selected model as well as Kimura 2-Parameter(K2P) model[22], which is the traditionally employed model in DNA barcoding result analysis. A dendrogram was constructed by the neighbour-joining (NJ) method according to the genetic distances calculated via different evolutionary models. Branch support for NJ was calculated using the bootstrapping method with 1 000 replicates.The topology of the resulting phylogenetic tree was used to evaluate the species monopoly.

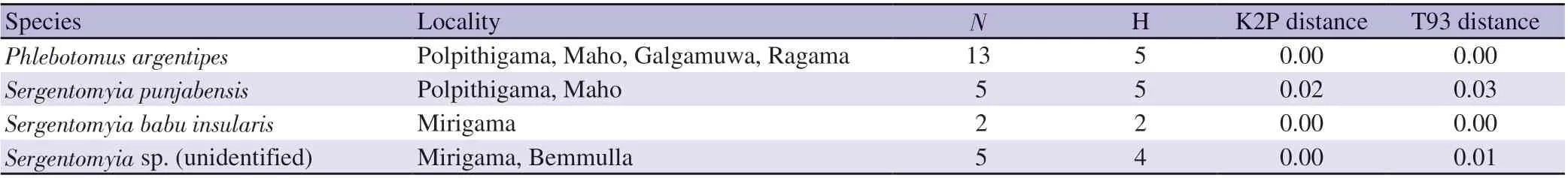

Table 1. Species of sand flies in genera Phlebotomus and Sergentomyia characterized by DNA barcoding.

Table 2. Minimum and maximum interspecific genetic distances according to two models used: K2P and TN93.

3. Results

3.1. Morphological characterization

A total of 38 441 sand flies were collected during the entomological surveillance. According to the morphological characterization,this collection consisted of four species under two genera, i.e.,Phlebotomus and Sergentomyia. The most common species was P. argentipes (n=38 218, 99.42%), followed by Sergentomyia (S.)punjabensis (n=192, 0.50%), Sergentomyia sp. which was not able to characterise to the species level by morphology (n=28, 0.07%)and S. babu insularis (n=3, 0.01%). The female to male ratios were 1: 6.25, 1:2.62 and 1:8.33 for P. argentipes, S. punjabensis and Sergentomyia sp., respectively. The S. babu insularis collection consisted of only male specimens.Female Phlebotomus was characterised by the wings being broader and asymmetrical, top to bottom. Also, the cibarium is unarmed or with scattered spicules without a pigment patch (Figure 2A). The sand flies of the genus Sergentomyia were characterised by having narrow and lanceolate wings (when the wing folded in half from top to bottom, the two halves would fit on top of each other) and cibarium having one or more rows of teeth (Figure 2B-2D). The pigment patch is usually presented in Sergentomyia sp.

The style had five spines in male Phlebotomus specimens (only P.argentipes) and subterminal spines were presented (Figure 3A). In all the collected Sergentomyia spp., the number of spines of the style was four. If all the spines are not terminal, two spines are terminal and two are sub-terminal and arranged in pairs (Figure 3B-3D).The morphological characterisation of the encountered species is described below.

3.1.1. Phlebotomus argentipes female

Head of the spermatheca does not consist of a neck.Spermatheca has around 16 segments and the apical segment is enlarged (Figure 4). Both the dorsal and lateral sides of the thorax are blackish. Wing overlap (R1 overlap with R2/complete length of R2) is approximately 0.2. The wing index (R2/R2+3) is around 2. The ratio between ascoid lengths to antennal flagellomere is approximately 0.4-0.5.

Figure 2. Cephalic structures of collected sand fly species (×1 000). A. Phlebotomus argentipes; B. Sergentomyia punjabensis; C. Sergentomyia babu insularis; D.Sergentomyia sp.

Figure 3. Terminal structures of collected sand fly species (×400). A. Phlebotomus argentipes; B. Sergentomyia punjabensis; C. Sergentomyia babu insularis; D.Sergentomyia sp.

Figure 4. Spermatheca of Phlebotomus argentipes (×1 000). The arrow indicates enlarged apical segment.

3.1.2. Phlebotomus argentipes male The paramere consists of 2 ventral processes. The style has five long spines, two of which are terminal and three are subterminal(Figure 3A). The ratio between gonocoxite and gonostyle lengths ranges from 1.72 to 1.74.

3.1.3. Sergentomyia punjabensis female The spermatheca is tubular and does not have a capsule or striation.The pharynx is broad at the posterior end and deep constriction at the base. Cibarium consists of approximately 29-30 teeth (Figure 2B).

3.1.4. Sergentomyia punjabensis male The Aedeagus is thick and finger-shaped (Figure 5) and all the cibarial teeth are arranged in one line.

3.1.5. Sergentomyia babu insularis female

Spermatheca consists of a smooth capsule. The pharynx has distinctly pointed teeth. Cibarium has a deep notch in the hind end of the ventral plate and cibarium with more than 45 teeth (Figure 2C).

Figure 5. Terminalia of Sergentomyia punjabensis (×400).

3.1.6. Unidentified Sergentomyia female

Spermatheca is tubular and consists of striations. Cibarium has three rows of fore-teeth (Figure 2D). Cibarium does not have a deep notch but the pigment patch is prominent.

3.1.7. Unidentified Sergentomyia male Aedeagus gradually tapers to the end. Paramere has hairy tubercles on the ventral side. Genital filaments have narrow ends. Gonostyle has four spines in pairs: one is terminal and the other is subterminal.These specimens are similar to S. zeylanica from the Aedeagus shape, paramere features, and the arrangement of the gonostyles.However, the shape of the spines differ, which are clavate in the new specimens (Figure 3D), whereas it was pointed in S. zeylanica.

3.2. Molecular characterization

A total of 25 sequences of 681 nucleotide pairs of the sand fly COⅠgene belonged to four species under two genera. One species from the genus Phlebotomus and three species in the genus Sergentomyia were among the recorded species. The most common species was P. argentipes, the known vector for Leishmania donovani in the South-Asian region. The three species of genus Sergentomyia were S. babu insularis, S. punjabensis and an unidentified Sergentomyia sp., which could be closely related to S.koloshanensis of the subgenus Neophlebotomus with an approximate 88% similarity (Table 1). Analysis of the nucleotide sequences of DNA fragments provided a coverage of 100% and a similarity of 98%-100% with the COⅠof Old World sand flies characterized in previous studies[23].

3.3. Nucleotide composition of sand fly COI gene

The majority of the nucleotide composition in the COⅠgene of the sand flies was made up of adenine (A), which contributed to 37.71% of the total nucleotides. About 28.63% of the nucleotide has been made up of thyamine, while guanine and cytosine contributed to 18.11% and 15.54% of the total nucleotides, respectively.

3.4. Interspecific and intraspecific variations

The multiple alignments of nucleotides indicated the presence of 166 polymorphic sites, 10 of them were singleton sites and 156 corresponded to phylogenetically informative sites with up to three variants distributed along the alignment. Analysis of intraspecific variations indicated that haplotypes per species varied from 2 to 5, where the highest values were observed for P. argentipes and S.punjabensis, followed by unidentified Sergentomyia sp. and S. babu insularis (Table 1).

The high degree of polymorphism observed in the nucleotide sequence remained in amino acid sequences. Multiple alignments of 215 amino acids indicated the presence of 108 variable sites,where 102 of them are parsimonially informative sites with up to six variants and six singleton sites. Nevertheless, no stop codons,insertions or deletions were encountered in the amino acid sequence.

3.5. Phylogenetic analysis

The intraspecific genetic distance with the K2P model was 0.02 for S. punjabensis, while it was zero for all three other species (Table 1).The calculation of intraspecific genetic distance by the T93 model showed 0.03 for S. punjabensis and 0.01 for the unidentified Sergentomyia sp. As observed for the K2P model, the genetic distance was zero for the other species. The interspecific genetic distance calculated using the K2P model ranged from 0.129 to 0.211 The genetic distance between species was ranged from 0.131 to 0.215 according to the TN93 model (Table 2).The dendrograms generated by the neighbour-joining (NJ) method with TN93 (Figure 6) and K2P (Figure 7) indicate that the two genera clustered separately and specimens from the same species clustered together. However, within the genus Sergentomyia, S.punjabensis and S. babu insularis are more closely related than the other unidentified Sergentomyia sp. All the species level separations were confirmed with 100% bootstrap values.

4. Discussion

Morphological identification of sand flies is somewhat complicated due to laborious microscopic examinations and dissections of very tiny specimens[24]. These procedures are highly time-consuming and require considerable skill and taxonomic expertise. Furthermore,morphological identification is limited as it is not ideal for damaged samples and identification may be difficult due to improper mounting of specimens. Therefore, molecular level identification has received wider attention for insect authentication[7].

In general, the use of a conserved region in the genome such as COⅠand internal transcribed spacer 2, which are used for the identification of various medically important insects[23,25]. The COⅠis considered the ideal primers for dipteran insects due to internal transcribed spacer 2 sequences that do not discriminate against some closely related species and sibling species[26]. Primers used in the present study targeting the COⅠregion have been used for mosquitoes and sand flies[23,27]. These primers (LCO 1490/HCO2198) have been used in many sand fly barcoding studies[7,23,28]. The amplification of COⅠnuclear pseudogenes of mitochondrial origin is one of the major issues encountered in DNA barcodingestriction profiles and sequence ambiguities in polymorphic sites. Furthermore, in conditions where both template strands are sequenced, the presence of frameshift mutations, stop codons, and unexpected phylogenetic relationships can also be seen[29]. Therefore, such potential can cause false interpretations.In the present study, no stop codons, insertions or deletions were encountered. Hence, the probability of co-amplification of nuclear pseudogenes of mitochondrial origin as well as pseudogenes can be excluded.

The nucleotide sequence length in the present investigation was 681 bp, in agreement with previous studies[29]. The relatively longer sequences ensure the accuracy in sequence-based identification of sand fly species. However, this is not consistent across other studies,as some investigations have reported shorter fragments, such as 549 bp and 548 bp[28,30], or longer lengths of sequences with 700 bp and 689 bp[7,23].

In the sequence of sand fly DNA, the content of A and T bases was higher (66.34%) than G and C (33.66%). These average values of A+T percentage observed during the current study were closer to the values reported previously for Dipterans[31-33]. The A+T values observed in this study were similar to the values observed for Lutzomyia species in South America[7,30] as well as Sergentomyia and Phlebotomus species from South Asia and the Mediterranean islands[23,34,35].

Codon usage indicates that the A+T at the third codon position is more common. This is reported widely for other sand flies[7,23,35]and supported by the fact that the nucleotide composition of insect mitochondrial DNA is correlated with codon usage because genes encoding mitochondrial proteins exhibit a preference for the use of codons rich in A+T[36,37]. This has been observed in other gene fragments of sand fly genome, such as NADHubiquinone oxidoreductase chain 4 (A+T=72.5%), cytochrome b(A+T=73.09%), serine transfer RNA (A+T=81.20%)[38-40].

The intraspecific genetic divergence from species in the same genus is usually associated with the geographical scale of the sampling site distribution[41,42]. The highest percentage of haplotypes were observed for S. babu insularis and S. punjabensis.However, the sample number was very low for both species due to the lower abundance. This prevents the comparison of intraspecific genetic diversity between species collected during the study. The interspecific genetic divergence was lower between the unidentified Sergentomyia sp. and S. babu insularis, which were collected from closer proximities. Therefore, it is apparent that these results align with the previous findings that reported the association of the geographical scale of sampling with the intraspecific genetic divergence.The substitutions in variable positions were largely synonymous and of the transitional type. This means a purine base substitute a purine base and a pyrimidine base are substituted by a pyrimidine base at the third position of the codon. Due to the changes in the third position are not chemically significant and the lack of tRNA specificity at wobble position, it does not change the amino acid that codon represents at the protein synthesis complex. Thus, does not affect the amino acid composition of the protein. However, the interspecific level sequence analyses indicated a gradual increase in substitution rates. Thus, the nucleotide substitution patterns could be considered a reliable diagnostic feature for species differentiation[23].It is important to note that the species denoted as the unidentified Sergentomyia sp. was not morphologically similar to any of the Sergentomyia species reported previously from Sri Lanka. Similar morphological characters shared by members of species complexes make the identification a difficult task based on morphological taxonomic keys. One of the other limitations in the morphological characterization is that some specimens may classify to the species level that shares similarities to most of the features in the existing identification key. Therefore, deviations in the morphology may not be considered and some new or unrecorded species may be neglected in the surveys. Hence, it is a need for an alternative,universally-applicable method to support the existing sand fly identification methods, which cannot be resolved through morphological characterization.According to the COⅠgene sequencing, the closest one was S.koloshanensis of the subgenus Neophlebotomus with an approximate 88% similarity. This may be because the Sergentomyia species observed in the present investigation is a new species or the COⅠgene has not been sequenced yet; thus, absent in the NCBI database. The identification of these specimens based on the morphology may lead to a wrong confirmation as S. zeylanica when considering the features of spermatheca and cibarium and the arrangement of gonostyles. However, these specimens differ from S. zeylanica in their characteristic shape of the gonostyle. None of the other described sand fly species is known to have clavate gonostyles. The similarity in morphology to S. zeylanica also depicts that this species may be a morphological variant of S. zeylanica or limited sequence availability as references for comparison have restricted its usage on species identification. These new sequences would also contribute to the ongoing global effort to standardize DNA barcoding as a molecular means of species identification by the Consortium for the Barcode of Life[23].

In summary, the findings of the present study suggested that COⅠbased DNA barcode can effectively be used when morphological traits of certain sand fly species do not clearly distinguish one species from another. Therefore, DNA barcodes also facilitate the taxonomists to re-confirm the reference voucher specimens. Hence, COⅠ-based molecular characterization would be a useful complementary tool for the identification of sand fly species.In this study, the applicability of COⅠ-based DNA barcoding in the identification of sand fly species in Sri Lanka was evaluated and the genetic variation of sand flies collected from two leishmaniasis endemic districts of Sri Lanka was characterized. Identification based on morphology and COⅠ-based barcoding confirmed four sand fly species encountered in study areas belonging to 2 genera. The most common species was P. argentipes, and the other three species were S. babu insularis, S. punjabensis and an unidentified Sergentomyia sp. Intraspecific genetic variation was higher for P. argentipes and S. punjabensis, collected from sites spread over a broader geographical scale than other species. P.argentipes show a clear genetic differentiation from other species.In the genus Sergentomyia, S. babu insularis and S. punjabensis showed a higher genetic affinity to each other than the unidentified species. Therefore, it is recommended to establish a reliable and standardized identification system for sand fly species found in Sri Lanka.In the collection of sand flies, some of the species had a smaller sample size due to the lower abundance in the environment.Repetitive collections did not include any new specimens from that species. Furthermore, the sample size had to be limited due to funding constraints. The sampling was done only in two districts considering the disease prevalence and the logistic issues.Expanding this study into other areas would be a needed next step.However, despite the limitations, this provides valuable information to conduct more studies highlighting the importance of further studies focused towards cryptic diversity of sand flies in Sri Lanka.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

National Research Council, Sri Lanka and Research Council,University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka are acknowledged for supporting the research activities.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Research Council, Sri Lanka (Grant No. NRC 16-142) and University of Kelaniya,Research Council (Grant No. RC/SROG/2021/03).

Authors’contributions

TW conducted the laboratory investigations, analysed the data and compiled the manuscript. WR processed sequencing data and supervised the study. NG supervised the research work, reviewed the manuscript and made critical revisions. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

杂志排行

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine的其它文章

- Hurdles in achieving the goal of malaria elimination by India

- Conventional treatments and non-PEGylated liposome encapsulated doxorubicin for visceral leishmaniasis: A scoping review

- Prevalence and factors associated with belief in COVID-19 vaccine efficacy in Indonesia: A cross-sectional study

- Mosquito larva distribution and natural Wolbachia infection in campus areas of Nakhon Ratchasima, Thailand

- A rare presentation of Guillain-Barre syndrome with GQ1b positivity: A case report