Biotechnology of the multipurpose tree species Arbutus unedo: a review

2022-04-17JoMartinsGlriaPintoJorgeCanhoto

João Martins·Glória Pinto·Jorge Canhoto

Abstract Arbutus unedo L. (strawberry tree, Ericaceae) is a woody species with a circum-Mediterranean distribution. It has considerable ecological relevance in southern European forests due to its resilience to abiotic and biotic stressors. Its edible red berries are used in the production of traditional products, including an expensive spirit. Several compounds extracted from the species have bioactive properties used by the cosmetic and pharmaceutical industries. The strawberry tree has gone from a neglected species to become a highly valuable crop with large cultivated areas in southern European and North African countries. Due to an increasing demand from farmers for plants with improved features, researchers have been trying to improve this species through conventional and biotechnological tools, focusing mainly on population analysis using molecular markers, in vitro cloning, tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses, and intraspecific crosses to obtain genotypes with new characteristics. The objective of this review is to gather and update information about the species and make it available to researchers and stakeholders. Future research areas that are considered a priority for this species are highlighted.

Keywords Breeding·Chemical profiling·Ericaceae·Microbiome·Micropropagation

Introduction

Arbutus unedoL., commonly known as the strawberry tree, has considerable economic potential. The edible fruits are used in the production of traditional products such as jam, jelly, and an alcoholic beverage, the latter representing its most valuable derived product. Each tree produces, on average, seven to 10 kg of fruit, and 10 kg are usually required to produce 1-L of spirit (Gomes and Canhoto 2009), obtained following fermentation and distillation. Strawberry tree honey is another typical product of some Mediterranean regions (Tuberoso et al. 2010), appreciated for its bitter flavor, intense odor and amber color, rich in amino acids and possessing antioxidant properties (Rosa et al. 2011). Its price is usually much higher than sweeter bee honey, as production is laborious and reduced owing to the time of the year (autumn) in which flowering occurs (Tuberoso et al. 2010). The species has been a source of biomass for energy production and in floriculture to compose floral bouquets due to the appealing light green color of its young leaves (Metaxas et al. 2004). The large amount of tannins in the bark make the species useful for tanning (Gomes et al. 2010). Moreover, several chemical compounds with bioactive properties have been identified in different parts of the plant with applications in the pharmaceutical, cosmetic and food industries (Migas and Krauze-Baranowska 2015).

A. unedowas once considered a neglected species and plants were almost exclusively found growing in the wild. However, phytosanitary problems with species once considered more interesting, such asPinus pinasterAit. andEucalyptus globulusLabill., as well as the intensity and frequency of fires associated with forest monocultures, have led to a renewed interest in this species, not only by policy-makers but also farmers and other stakeholders (Garrido and Silveira 2020; Silveira 2020). As a consequence, orchards have been established and production areas have been increasing over the years, especially in Portugal, which is currently the largest world producer of this small berry (Garrido and Silveira 2020). Nevertheless, to obtain maximum revenues, producers are looking for plants with improved traits, such as high fruit production, tolerance to pathogens and drought stress, which are currently unavailable in the markets. In order to fulfill such demands, it is essential to implement breeding programs by selecting plants with interesting characteristics and to obtain cultivars with improved traits. This review was designed based on what would be a four-phase improvement program (Fig. 1), namely: characterization of the wild populations Distribution, botanical description and phenology" section; selection of plants with interesting characteristics "Ecological importance" section; conservation and propagation of the selected genotypes "Genetic characterization" section; and, breeding using different techniques "Population analysis and plant selection" section. Population analysis would be conducted at genetic and chemical levels, and also by the characterization of associated microbiomes. Such information is essential to define a criterion for plant selection and for further conservation and multiplication. Several breeding techniques can also be used to obtain new genetic combinations and plants with improved traits.

Fig. 1 Scheme of a breeding program for the strawberry tree with four major steps: (1) population analysis, (2) selection, (3) conservation and multiplication and (4) breeding

Information about the innumerous techniques successfully applied to the strawberry tree that can be of help in future breeding programs, including in the selection, conservation and propagation steps, will be discussed in the following sections. An overview of the species potential as a crop species for several industrial applications is also provided by bringing together available information about its botanical and chemical features. In spite of the large volume of literature, research to-date has not addressed major areas that might be crucial in the development of a successful long-term breeding program, thus compromising its feasibility. Some of these limitations are discussed in this review as well as the benefits and challenges of a future breeding program.

Distribution, botanical description and phenology

TheArbutusgenus belongs to the cosmopolitan Ericaceae family, which represents 2% of all the eudicotyledons, plants with two seed leaves upon germination. It includes about 12 accepted species distributed along the west coast of the United States and Canada, Central America, Western Europe, the Mediterranean Basin, North Africa and the Middle East (Heywood 1993; Stevens 2001). Some of the species, such asArbutus canariensis(Lindl.) andArbutus menziesii(Pursh.) possess typical Mediterranean characteristics (Piotto et al. 2001). One of the most important economic species of the genus isArbutus unedoL. (Gomes and Canhoto 2009), a small tree (Fig. 2a) that can withstand temperatures as low as -12 °C (Mereti et al. 2002) and is tolerant to drought (Munné-Bosch and Peñuelas 2004). Considered a relic of a warmer period previous to the last Würm glaciation (Ribeiro et al. 2019), the strawberry tree usually grows on acidic, rocky, and well-drained soils along the Mediterranean Basin from Spain to Turkey, in some regions in North Africa, the Mediterranean Islands and the Atlantic coast of France, Ireland, and Portugal (Fig. 2b; Torres et al. 2002). It usually grows in shrub communities or forests associated with species of the generaQuercusandPinus(Prada and Arizpe 2008).

The leaves are petiolate, oblong-lanceolate and usually toothed, an intense light- green when juvenile and darker when mature. They display a lauroid morphology, resembling laurel leaves, inherited from its ancestors which colonized Europe in a subtropical environment during the Tertiary (Silva 2007). The hermaphrodite flowers are bellshaped (Fig. 2c), whitish to slightly pink and arranged in hanging panicles (up to 30 flowers). The corolla is sympetalae, i.e., with fused petals, and pollination is entomophilous, insect pollinated (Prada and Arizpe 2008). The fruit is a spherical berry (Fig. 2d), about 20 mm in diameter, covered with conical papillae. They generally contain 10 to 50 small seeds which are dispersed by endozoochory, by birds and mammals (Piotto et al. 2001).A. unedonaturally hybridizes withA. andrachneL. resulting in the hybridA.×andrachnoidesLint. Another recognized hybrid isA.×androsterilis(Salas et al. 1993), which is obtained by crossingA. unedowithA. canariensis(Torres et al. 2002; Prada and Arizpe 2008).

Fig. 2 a Arbutus unedo, b distribution around the Mediterranean basin and the Atlantic coast of Portugal, Spain, France, and Ireland, c bell-shaped flowers being pollinated by a honey bee (Apis melifera, arrow), and d fruit at different ripening stages and flowers (arrow)

The phenological cycle of the strawberry tree is slow and lasts for almost two years. During this period, three distinct stages can be observed: flower buds, blooming and fruiting. The first flower buds begin to form in June and remain in a state of apparent quiescence for several months. Flower anthesis usually begins in October and may last until January. After fertilization, the long fruit development process starts, taking at least nine months to be completed. The color of the fruit markedly changes during fruit development, passing through green, yellow, orange and finally red when mature. In autumn, flowers and fruit can be found simultaneously on the same tree (Fig. 2d; Villa 1982). The ovary is pentalocular, each locule enclosing several ovules (Takrouni and Boussaid 2010). According to Villa (1982), the ovules are already within the flower buds formed in June but are not yet completely organized. The differentiation of the nucellus occurs only in September when the ovules assume their final position inside the ovary with the micropyle in front of the placenta, termed anatropous ovules. After fertilization, the zygote remains in a state of dormancy for approximately six months. After this period, the first division of the zygote occurs and embryo development proceeds at a rather slow pace, and several months are needed for complete formation (Villa 1982).

Ecological importance

The strawberry tree is a key species of Mediterranean ecosystems, especially on marginal lands where thermal amplitudes are high and water is scarce in summer months, and where other species face difficulties to thrive.A. unedoprovides food and shelter to various fauna and helps to stabilize soils, avoiding erosion and promoting water retention. Furthermore, it has a great regeneration ability after forest fires (Piotto et al. 2001), a feature that makes the species interesting for reforestation programs. This is particularly important in southern European countries such as Portugal, Spain and Greece where fires are routine during hot, dry summer months. The species has also shown potential to be used in phytostabilization programs due to its tolerance to heavy metals (Godinho et al. 2010). Some phenolic compounds produced by the strawberry tree as secondary metabolites are believed to be involved in the regulation of the nitrogen cycle, keeping low concentrations of nitrates in the soil. The inhibition of nitrification would also block NO2, one of the gases responsible for the greenhouse effect (Castaldi et al. 2009).

Population analysis and plant selection

In a tree species with a long-life cycle such as the strawberry tree, selection and breeding can be time- consuming. Thus, a good characterization of wild populations and the development of molecular markers are essential to speed up the selection process. Molecular markers can also be useful for in situ and ex situ germplasm conservation, as insights about population evolution and diversity can be obtained. Studies of genetic diversity and population structure provide essential knowledge for forest management and selection of individuals and/or populations for breeding and conservation purposes.

A chemical characterization of the plants is equally important to identify specific chemotypes, especially as a selection criterion. Another important component of the plant that should not be neglected is its microbiome. These micro-organisms play a crucial role in host resistance against adverse conditions including pathogen attacks, either by direct competition and antagonism or by promoting plant defense mechanisms (Turner et al. 2013). Additionally, endophytes produce a large number of compounds with interesting properties that can be used for numerous applications, including the treatment of human diseases (Kusari et al. 2012), widening the spectrum of possible applications for endophytes. Finally,A. unedoorchards are often established on marginal lands and dry sites where plants are prone to drought stress. In addition, extreme climate events are expected to occur more frequently in the future, leading to reduced precipitation and increasing temperatures (Polle et al. 2019). In this scenario, changes in the species distribution are expected to occur due to habitat loss in southern regions (Ribeiro et al. 2019). Thus, resistance to drought is one of the vital traits to be pursued in selection and breeding. Knowledge of stress tolerance mechanisms and characterization of their microbiome might be essential for plant survival and to ensure productivity of orchards. Such information is useful for plant selection and to develop forest and agricultural management strategies that ameliorate plant growth and production under stress conditions.

Genetic characterization

Population genetic studies and the development of molecular markers are essential to significantly reduce the time necessary in the selection and breeding of new varieties. The genetic structure of the strawberry tree population has been studied using different approaches and several molecular markers have been developed, including RAPD, ISSR, cpSSR and AFLP (Takrouni and Boussaid 2010; Lopes et al. 2012; Takrouni et al. 2012; Gomes et al. 2013a; Santiso et al. 2016; Ribeiro et al. 2017). A low to moderate level of differentiation was generally found in the populations studied, attributed to a high gene flow caused by the long seed dispersal distances. Furthermore, cluster analysis of the populations showed that there was no relation to a bioclimatic or geographical origin of the species, demonstrating that differentiation occurs at a local scale. Thus, a higher level of genetic variation is usually found within a population than between different populations.

Based on these findings, researchers have proposed an ex situ and/or in situ conservation strategy and genotype selection that takes into account the genetic diversity within populations, and based on the selection of a large number of individuals from the same population (Takrouni and Boussaid 2010; Lopes et al. 2012; Takrouni et al. 2012; Gomes et al. 2013a).

Chemical fingerprint

The species is a source of bioactive compounds, and several studies have been carried out providing a chemical fingerprint from different parts of the plant and collected at different seasons and locations, such as in Portugal, Spain, Italy, Turkey and Algeria. Analysis of the distillate and honey was also carried out. Amongst the considerable variety of compounds produced by the species, some had interesting bioactive properties, with the potential for use by pharmaceutical, cosmetic and food industries, thus increasing the species economic value. Such information is also be relevant for the selection of plants with specific chemical properties for propagation and breeding.

Fruit

Phenolic acids, galloyl derivatives, flavonols, flavan-3-ols and anthocyanins have been identified as main fruit components (Ayaz et al. 2000; Pawlowska et al. 2006; Pallauf et al. 2008; Fortalezas et al. 2010; Mendes et al. 2011; Guimarães et al. 2013). Unsaturated fatty acids (α-Linolenic, linoleic and oleic acids) and saturated fatty acids (palmitic acid) (Barros et al. 2010; Morales et al. 2013), vitamin E (Pallauf et al. 2008; Barros et al. 2010; Oliveira et al. 2011a; Morales et al. 2013) and vitamin C (Alarcão-e-Silva et al. 2001; Pallauf et al. 2008; Şeker and Toplu 2010; Ruiz-Rodríguez et al. 2011; Morales et al. 2013) have also been identified, as well as several organic acids such as fumaric, lactic, malic, suberic, citric, quinic and oxalic acids (Ayaz et al. 2000; Alarcão-e-Silva et al. 2001; Ruiz-Rodríguez et al. 2011; Morales et al. 2013). The fruit has high amounts of fructose and glucose and low levels of sucrose and maltose (Ayaz et al. 2000; Alarcão-e-Silva et al. 2001; Şeker and Toplu 2010; Ruiz-Rodríguez et al. 2011), and several minerals in its composition include calcium, potassium, magnesium, sodium, phosphorus and iron (Özcan and Haciseferogullan 2007; Şeker and Toplu 2010; Ruiz-Rodríguez et al. 2011). Composition and concentrations of some compounds such as vitamins, organic acids and sugars might depend on fruit ripening stage, the season and geography (Alarcão-e-Silva et al. 2001; Ruiz-Rodríguez et al. 2011).

Leaves

Polyphenol profiles ofA. unedoleaves are mainly composed of arbutin, hydroquinone and their derivatives, gallic acid derivatives, tannins and flavonoids like quercetin, kaempferol and myricetin derivatives (Pavlović et al. 2009; Tavares et al. 2010; Mendes et al. 2011; Maleš et al. 2013).

Volatile compounds and essential oils

Several volatiles from the aerial parts of the plant have been identified, nonanal and decanal the most abundant (Owen et al. 1997). Alcohols such as (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol, 1-hexanol, hexanal, (E)-2-hexenal and (Z)-3-hex-enyl acetate are the main volatile compounds found in fruit at different ripening stages, followed by aldehydes and esters (Oliveira et al. 2011b). The essential oils of leaves were also studied. Among the 37 constituents found by Kivcak et al. (2001), (E)-2-decenal, α- terpineol, hexadecanoic acid and (E)-2-undecenal were the major constituents, while palmitic acid, linoleic acid and p-cresol, 2,6-di-tert-butyl were the major constituents identified by Bessah and Benyoussef (2012).

Bioactive properties

The traditional use of the leaves as a diuretic, urinary antiseptic, depurative and as an antihypertensive has been reported in the literature. In fact, several bioactive properties have been described, such as the antioxidant activity of the leaf extracts (Pabuçcuoǧlu et al. 2003; Oliveira et al. 2009; Pavlović et al. 2009; Orak et al. 2011; Malheiro et al. 2012; Boulanouar et al. 2013) and fruit (Barros et al. 2010; Fortalezas et al. 2010; Şeker and Toplu 2010; Oliveira et al. 2011a; Akay et al. 2011; Morales et al. 2013; Guimarães et al. 2014), as well as antimicrobial activity against some bacteria and molds (Orak et al. 2011; Malheiro et al. 2012; Ferreira et al. 2012; Dib et al. 2013). Other properties including anti-inflammatory (Carcache-Blanco et al. 2006; Mariotto et al. 2008b), antitumoral (Carcache-Blanco et al. 2006; Mariotto et al. 2008a), and vasodilator (Legssyer et al. 2004; Afkir et al. 2008) have also been described. Owing to their antioxidant properties, some compounds have the potential to be used by food industries, for instance, in meat processed products (Armenteros et al. 2013; Ganhão et al. 2013).

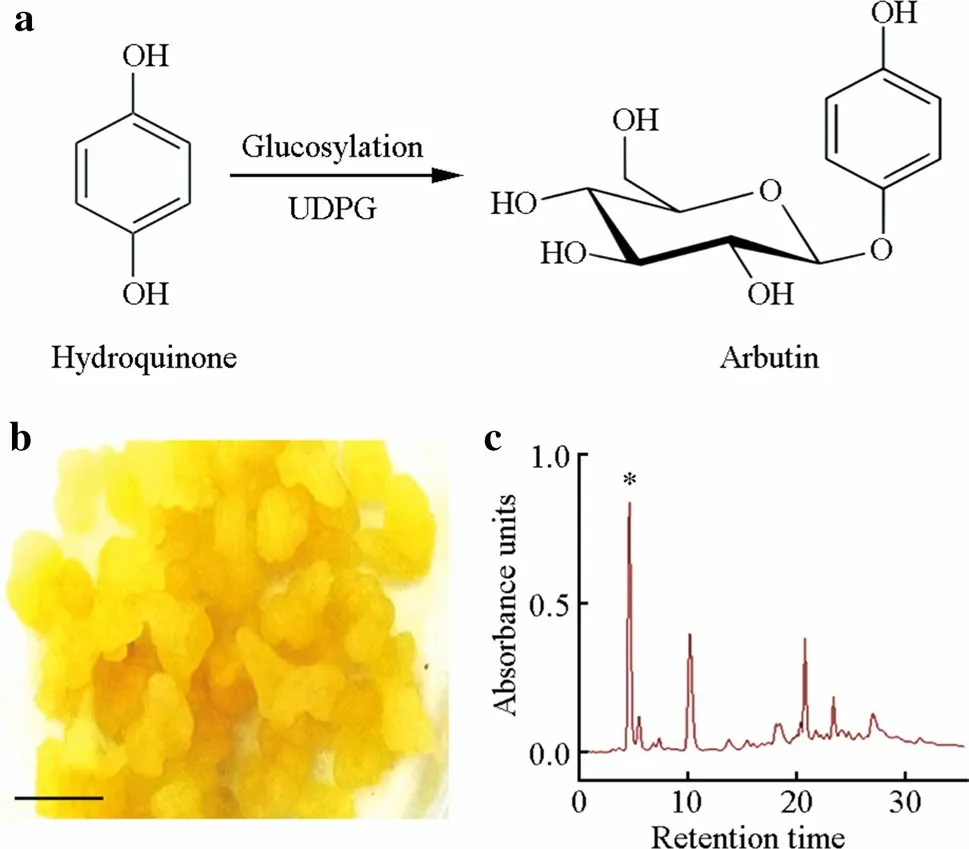

Because of the several bioactivities identified, these natural compounds can be exploited for pharmaceutical and chemical applications in the prevention or treatment of several human diseases. In fact, arbutin is already used by cosmetic industries as a skin whitening agent, and along with its precursor hydroquinone, is used in the formulation of commercial remedies for the treatment of urinary infections (Migas and Krauze-Baranowska 2015; Jurica et al. 2017). Due to the economic value of arbutin, our group has been working on the development of a biotransformation protocol in order to produce arbutin (data not published). The strawberry tree has the ability to convert hydroquinone into arbutin through glycosylation (Fig. 3a). Using cell suspensions (Fig. 3b) and/or shoot segments in vitro, high amounts of this phenol can be obtained (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3 a Glycosylation process of hydroquinone into arbutin, b calluses used in the biotransformation of hydroquinone into arbutin (bar = 50 mm), and c chromatogram of the extract recovered from the biotransformation with the arbutin peak (*)

Distillate and honey

Chemical analysis of the distillate have been carried out (Soufleros et al. 2005) and different microorganisms were identified during the fermentation of the berries (Cavaco et al. 2007; Santo et al. 2012) which contribute to the chemical characteristics of the distillate.

Strawberry tree honey is rich in amino acids and have antioxidant properties (Rosa et al. 2011). Homogentisic acid has been identified as a possible marker for this honey (Tuberoso et al. 2010). Other substances, such as ( ±)-2-cis,4-trans-abscisic acid (c,t-ABA), ( ±)-2-trans,4-trans-abscisic acid (t,t-ABA) and unedone, can be used as complementary markers in the identification of this unifloral honey (Spano et al. 2006; Tuberoso et al. 2010).

Microbiome

Endophyte organisms have a symbiotic relationship with plants without causing any disease symptoms and might be advantageous to their host by producing growth promoting hormones and antimicrobial compounds (Firáková et al. 2007; Waqas et al. 2012; Kusari et al. 2012). Several fungi have been found to be strawberry tree endophytes such as:Allantophomopsis lycopodina,Alternaria alternata,Aureobasidium pullulans,Cladosporiumspp.,Cryptosporiopsis diversispora,Discostromaspp.,Microsphaeropsis olivacea,Penicilliumspp.,Stemphylium globuliferumandUmbelopsisspp. (Borges 2014), andTalaromyces pinophilus(Vinale et al. 2017). Endophytes were also found on other members of theEricaceaefamily (Rhododendronspp.,Enkianthus perulatusandPieris japonica),Alternariaspp.,Aureobasidium pullulans,Cladosporiumsp. andPenicilliumspp., as well as on several other taxa such asAspergillus,Colletotrichum,Fusarium,Glomerella,Phoma,Phomopsis,SeptoriaandTrichoderma(Okane et al. 1998; Purmale et al. 2012). Strawberry tree endophytes produce several volatile compounds and show antimicrobial activity (Borges 2014). The trees are likely to be affected by biotic stress, in particular by plant pathogens. Several fungi have been identified as causing foliar diseases on strawberry tree such as:Alternariaspp. (Thomma 2003),Glomerellaspp. (sexual stage ofColletotricumspp.) (Polizzi et al. 2011),Mycosphaerellaspp. (sexual stage ofSeptoriaspp.) (Romero-Martin and Trapero-Casas 2003) andHendersonula toruloidea(Tsahouridou and Thanassoulopoulos 2000).Phytophthora cinnamomi, a wide spread invasive oomycete that causes root rot has also been found onA. unedo(Moreira and Martins 2005; Moralejo et al. 2008).

Drought stress

As one of the most restrictive factors on plant growth (Guarnaschelli et al. 2012), water balance is strongly regulated by plants and have developed diverse adaptive characteristics and resistance mechanisms, both morphological and physiological, including a tight stomatal control and osmotic adjustment, as well as resistance to cavitation, deep rooting, leaf thickness and cuticular waxes (Gratani and Ghia 2002; Bussotti et al. 2014). As expected for a drought tolerant species,A. unedohas developed some of these features (Castell and Terradas 1994; Ogaya et al. 2003; Munné-Bosch and Peñuelas 2004). As part of its protection mechanism against drought, the strawberry tree has developed a conservative water- use strategy. Under water scarcity conditions, photosynthesis is adjusted and stomata close, leading to an accumulation of carbon dioxide (Martins et al. 2019)-a typical behavior of an isohydric species (Raimondo et al. 2015).

Germplasm conservation and micropropagation

The multiplication of the selected and improved plants obtained in breeding programs is essential to provide such genotypes for producers. This can be achieved using conventional methods and micropropagation techniques. So far, seed orchards constitute most of the production area, but the demand for cloned plants has increased considerably in recent years, and micropropagation techniques might be crucial to fulfill these demands. The ex situ conservation of this germplasm is also very important and can be accomplished through micropropagation and/or cryopreservation.

Conventional propagation methods

The propagation ofA. unedocan be achieved through conventional methods such as using cuttings or seeds. Propagation with cuttings allows for the cloning of specific genotypes. Although Metaxas et al (2004) obtained rooting rates higher than 90% using indole-3-butyric acid, potassium salt (K-IBA), this technique can be difficult to apply on the strawberry tree. Among other limitations, it proved to be genotype-dependent, and rooting rates as low as 22.2% were obtained on one of the tested genotypes.

Alternatively, propagation by seed is usually a rapid and easy method of propagation. However,A. unedoseeds are characterized by a physiological dormancy which impairs propagation through this method (Tilki 2004; Demirsoy et al. 2010; Ertekin and Kirdar 2010). Different methods can be applied to overcome seed dormancy, such as stratification, scarification and treatment with gibberellins (Tilki 2004; Demirsoy et al. 2010; Ertekin and Kirdar 2010), and several studies have been carried out to increase germination rates. Smiris et al. (2006) achieved germination close to 86% with a combined treatment of 24 h in gibberellic acid (GA3, 500 mg L-1) followed by three months stratification at 2-4 °C. In a study carried out by Tilki (2004), the highest germination percentage was 89% following seed treated with GA3(600 mg L-1). In the same study, seeds subjected to nine weeks stratification at 4 °C showed a germination rate of 86%. Ertekin and Kirdar (2010) obtained germination percentages of 85% at 90 days stratification at 4 °C or 60 days at 9 °C. Demirsoy et al. (2010) tested five different genotypes and obtained a maximum germination of approximately 43% with seeds stratified for 15 weeks at 4 °C without significant differences among genotypes. Germination rates higher than 90% have also been obtained by our research group with seeds stratified at 4 °C for 4 weeks (Martins 2012).

Due to the simplicity of this propagation technique, the study of seed dormancy ofA. unedohas a considerable economic and practical interest (Smiris et al. 2006). Moreover, sexual propagation promotes genetic diversity, which is of particular important for habitat restoration purposes. However, it does not allow the production of true-to-type plants and the multiplication of selected genotypes with specific characteristics-a drawback when the objective is to establish orchards.

In vitro propagation

To overcome the limitations of conventional propagation techniques, micropropagation appears to be the best alternative. Besides the production of cloned plants, micropropagation techniques have other advantages when compared to conventional cloning: they are not dependent on the time of the year, a small quantity of initial plant material is required, the entire process is carried out under aseptic conditions (thus ensuring the phytosanitary quality of the propagated materials), and a large number of cloned plants can be obtained (Chawla 2009). Micropropagation techniques can also be useful for germplasm conservation purposes. The most common micropropagation techniques on woody plants are: shoot proliferation (from apices or nodal segments), organogenesis, and somatic embryogenesis.

In vitro propagation protocols have already been developed forA. unedo(Fig. 4a) through axillary shoot propagation (Mereti et al. 2002; Gomes and Canhoto 2009; Martins et al. 2019) as well as organogenesis (Martins et al. 2019) and somatic embryogenesis (Martins et al. 2016a).

Axillary shoot proliferation

The propagation of the species through axillary shoot proliferation can be achieved using woody plant medium minerals (WPM, Lloyd and McCown 1980), supplemented with Murashige and Skoog vitamins (MS, Murashige and Skoog 1962) and 5 mg L-16-benzylaminopurine (BAP) (Mereti et al. 2002), or using De Fossard medium (De Fossard et al. 1974) supplemented with MS micronutrients and 2 mg L-1BAP (Gomes and Canhoto 2009). Other cytokinins, such as kinetin and zeatin, can also be used with similar results (Gomes et al. 2010). Axillary shoot proliferation of the strawberry tree can also be accomplished in liquid media (Fig. 4b, Martins et al. 2019). Higher multiplication rates can be obtained using this method when compared to propagation on solid media, which allows reduction of costs. However, shoots obtained by this method show signs of hyperhydricity or excessive hydration, resulting in poor lignification and several anatomical malformations (Marques et al. 2020). Nevertheless, plants recover their normal phenotype during acclimatization and have normal physiological functions under water stress (Martins et al. 2019). High rooting rates of the micropropagated shoots can be obtained either with indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) or indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) (Mereti et al. 2002; Gomes and Canhoto 2009), and plants can be easily acclimatized (Fig. 4c). According to Gomes et al. (2010), the genotype of the donor plants plays an important role in the multiplication rates, and the conditions used in the multiplication phase can also interfere in the rooting process. Several other members of the Ericaceae family have also been propagated through axillary shoot proliferation:Arbutus xalapensisKunth. (Mackay 1996),Calluna vulgaris(L.) Hull (Gebhardt and Friedrich 1987),Gaultheria fragantissima(Bantawa et al. 2011),Elliottia racemoseMuhl. ex Elliot (Radcliffe et al. 2011),Rhododendronspp. (Anderson 1984; Douglas 1984; Almeida et al. 2005) andVacciniumspp. (Pereira 2006; Biol et al. 2015).

Fig. 4 a In vitro establishment and micropropagation of strawberry tree using different techniques, including axillary shoot proliferation, organogenesis and somatic embryogenesis; b axillary shoot proliferation in liquid medium; c acclimatized plants obtained by axillary

Organogenesis

Organogenesis is the formation of adventitious shoots induced from shoot meristems, usually from a pre-formed callus. This method has a great potential for mass propagation because a large number of shoots can be formed from a single explant. The strawberry tree can be successfully micropropagated through organogenesis (Martins et al. 2019). Calluses with organogenic potential can be induced with thidiazuron, a plant hormone, on leaves of micropropagated shoots (Fig. 4d). The meristematic regions formed will produce new shoots when the callus is cultured on a medium with BAP (Fig. 4e). A similar method has been successfully applied to other members of the Ericaceae family, such asGaultheria fragrantissimaWall. (Ranyaphia et al. 2011),Rhododendronspp. (Harbage and Stimart 1987; Imel and Preece 1988; Iapichino et al. 1992; Mertens et al. 1996; Tomsone and Gertnere 2003) andVacciniumspp. (Cao et al. 2002; Debnath 2003).shoot proliferation; dcalluseswith organogenic capacity; e shoot obtained through organogenesis; and, f developing somatic embryos on a leaf explant (bar = 50 mm)

Somatic embryogenesis

Somatic embryogenesis is a useful tool for clonal propagation and for plant development studies, allowing for a comparison with zygotic embryogenesis. Somatic embryos can be obtained in large numbers and can be germinated, stored or used for the production of artificial seeds. Different tissues such as zygotic embryos, roots, stem segments and shoot tips, young leaves, sepals, and petals can be used as explants. Somatic embryogenesis is usually affected by several variables such as the genotype and physiological condition of the donor plant, type of explant, culture conditions and especially, the composition of the medium.

A somatic embryogenesis induction protocol has been developed for the strawberry tree from leaves of shoots propagated in vitro through axillary shoot proliferation (Martins et al. 2016a, 2016b). The embryos are obtained from a callus when segments of young leaves are cultured on Anderson medium (Anderson 1984) supplemented with 2 mg L-1BAP and 4 mg L-1of 1-naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) in a onestep protocol. Somatic embryos start to form 1.5-2 months after the beginning of the culture (Fig. 4f), and their conversion into plantlets is accomplished using the Knop medium (Knop 1865) without plant growth regulators, leading to the formation of plantlets with a well-developed root system. This technique has also been successfully applied on other Ericaceae such asConostephium pendulum(Anthony et al. 2004a),Elliotia racemosaMuhl. ex Elliot (Seong and Wetzstein 2008),Leucopogon verticillatus(Anthony et al. 2004b) andRhododendron catawbienseMichx. (Vejsadová and Petrová 2003).

Cryopreservation

Cryopreservation is a useful technique for germplasm maintenance ex situ, either for conservation and/or breeding purposes. It is cost- effective and allows for the preservation of large numbers of material for large periods of time. Unlike micropropagation, plant material does not undergo somaclonal variation and there is no risk of contamination (Panis and Lambardi 2006). Damiano et al. (2007) were the first to develop a cryopreservation protocol for the strawberry tree. It consisted of the culture of shoot apices in WPM or MS solid media with different concentrations of plant growth regulators. After this period, the apices were encapsulated in 3% alginate and cultured in liquid MS medium over one to seven days with different concentrations of sucrose. After the desiccation period, which was performed on silica gel for up to 24 h, the beads were immersed in liquid nitrogen, transferred to the propagation medium and after two weeks, the apices turned green and started to develop. The maximum regrowth rate (45%) was obtained when the encapsulated apices were pre-cultured on a medium containing 0.75 M sucrose for one day and the desiccation done for 14 h.

Plant breeding

Extensive work has been carried out with other members of the Ericaceae such asRhododendronspp. (Doorenbos 1955; Escaravage et al. 1997) andVacciniumspp. (Lyrene 1997; Usui et al. 2005; Drummond 2019) in order to characterize the pollination and breeding system of these species and to obtain new varieties with interesting traits. A characterization study of pollen morphology and germination has also been done forA. unedo, as well as in vitro and in vivo controlled pollination between selected plants which produced several hybrids (Martins and Canhoto 2014). However, this method can be time- consuming for species with long lifecycles, making it essential to develop a set of tools to speedup the breeding process. The identification of QTL (quantitative trait loci) associated with marker assisted selection (MAS) has been applied to other woody species and may also be applied toA. unedo(Butcher and Southerton 2007). Several other techniques have be applied for this purpose, such as polyploidization, mutagenesis, mycorrhization and genetic transformation (Navarro and Morte 2009; Antunes 2010; Gomes et al. 2013b, 2016; Martins and Canhoto 2014).

Mycorrhization

Mycorrhization is often an advantage, particularly for woody plants, as it increases mineral and water uptake, stimulating growth and production (Gomes et al. 2013b). Mycorrhization with edible species of fungi may also constitute an additional revenue for producers. In vitro synthesis of arbutoid mycorrhizae on strawberry tree plants was accomplished with twoLactarius deliciosusisolates, which persisted for nine months after the acclimatization of the plants (Gomes et al. 2016). Fungus-plant host compatibility has also been tested with two other different fungi species:Pisolithus tinctorius(Pers.) Coker and Couch (Navarro and Morte 2009) andPisolithus arhizus(Scop.) Rauschert (Gomes et al. 2013b). The association ofA. unedowithP. tinctoriusincreased plant height and had a beneficial effect on root system development. The higher stomatal conductance values in the mycorrhizal plants led to higher photosynthetic activity. A combined treatment with paclobutrazol was the most efficient, improving both nutritional and water status. With regards toP. arhizus, one month after in vitro inoculation, arbutoid mycorrhizae were observed, which indicates the compatibility of the fungus with the strawberry tree. However, in a field trial, the presence of the fungi previously inoculated was not observed in the roots of 20 months old plants, suggesting that fungal persistence can be a problem once plants establish mycorrhizae with natural fungi species (Gomes et al. 2013b).

Polyploidization

Although most of the wild plant species are diploid, polyploidy is a common phenomenon in both crop species and in wild populations, estimated to occur in approximately 70% of Angiosperms. The duplication of chromosomes has been used in horticulture as a tool to obtain higher quality plants with improved yield, as polyploidy can lead to thicker leaves, more intense colors, larger flowers and leaves, longer flowering periods, disease resistance, increased fruit size, and resistance to environmental stress (Väinölä 2000). Additionally, this technique can also be used to restore fertility or to prevent sterility of hybrids resulting from crosses between plants with different ploidy levels. Tetraploid plants can also be crossed with diploid plants to obtain sterile triploids (Väinölä 2000) which, in some cases, produce seedless fruits through parthenocarpy, fruit development without prior fertilization,-a feature highly appreciated by consumers (Picarella and Mazzucato 2019).

Attempts to obtainA. unedotetraploid plants have been carried out by Antunes (2010). Nodal segments micropropagated in vitro were treated with two c-mitotic agents (colchicine and oryzalin) in solid and liquid media. However, the majority of the treated plants remained diploid; some became mixoploid and a single tetraploid shoot was obtained in solid medium containing 125 μM oryzalin. A second attempt was carried out under similar conditions by Martins and Canhoto (2014). Several mixoploid plants were obtained but only three were tetraploid after a treatment with oryzalin, representing a low conversion rate (1%). This problem was compounded by the fact that the tetraploid plants died a few weeks after the treatment with the c-mitotic agent. Together, these findings suggest chromosome duplication is difficult to achieve withA. unedoand a tetraploid genome is very unstable, which might be a major drawback on future attempts to obtain tetraploid plants. Nevertheless, despite the possible limitations of this method, tetraploid plants were successfully obtained on other woody Ericaceae, such asRhododendronspp. andVacciniumspp. (Väinölä 2000; Chavez and Lyrene 2009), which opens up good prospects to obtain strawberry tree tetraploid plants.

Conclusions and future prospects

From a neglected species,A. unedohas caught the attention of local authorities, farmers and other stakeholders. Due to its resistance to abiotic and biotic stresses, the ability to colonize marginal lands and its regenerative capacity following forest fires, the strawberry tree has the potential to become one of the more important species in the Mediterranean region. Extensive work has been done in recent years and several biotechnological tools have been developed. Population genetic studies have provided critical information for the conservation and selection of individuals in wild populations, while micropropagation techniques have shown an efficient way of ex situ conservation and multiplication. Some studies have highlighted the tolerance mechanisms of the species against abiotic and biotic stress and a broad chemical fingerprint has been obtained. Its potential for the pharmaceutical, cosmetic and food industries has been increasingly more relevant.

Nevertheless, some important pieces of this complex puzzle are still missing and require attention. The chemical analysis carried out so far did not evaluate the role of plant genotypes and the effect of abiotic stimuli on quantitative and qualitative chemical composition. The ecological relevance of such compounds has also been neglected as studies tend to focus on pharmaceutical applications. Thus, the involvement of such compounds on plant development and defense mechanisms are poorly understood, as is its interaction with the plant’s microbiome. The study of endophyte communities has also been limited and little is known about the interaction and relevance of these microorganisms and their interaction with their host. In addition, endophytic bacteria have never been studied and non-culturable microorganisms are a grey field with this species. The impact of pathogens onA. unedosurvival and production is unknown. Due to its relevance in plant selection and breeding, better understanding of plant-pathogen interactions is necessary. This could also lead to more efficient and eco-friendly plant protection strategies. A basic understanding of the physiological response ofA. unedounder water deficits has been achieved, but the related biochemical and molecular mechanisms are poorly understood. Finally, the first attempts of breeding using different approaches are a step forward, but much lies ahead in obtaining newA. unedovarieties with improved characteristics. Together, this knowledge constitutes a good basis for future breeding programs and builds the potential of the species, opening the way for future biotechnological applications. We are currently working in several of the above topics, such as the improvement of the somatic embryogenesis induction protocol. Additionally, our research has also been focused on the reproduction ofA. unedoas well as breeding and selection of plants tolerant to water stress. Further work will also be carried out to uncover the physiological and molecular mechanisms behind drought resistance. A detailed analysis ofA. unedomicrobiome and its role in plant defense is another topic that our research has been addressing. Much remains to be done to develop a breeding program and fully seize its potential.

杂志排行

Journal of Forestry Research的其它文章

- Molecular characterization and functional analysis of daf‑8 in the pinewood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus

- Modeling habitat suitability and utilization of the last surviving populations of fallow deer (Dama dama Linnaeus, 1758)

- The identification and pathogenicity of Fusarium oxysporum causing acacia seedling wilt disease

- Growth and decline of arboreal fungi that prey on Bursaphelenchus xylophilus and their predation rate

- Volatile metabolites of willows determining host discrimination by adult Plagiodera versicolora

- Soil ecosystem changes by vegetation on old-field sites over five decades in the Brazilian Atlantic forest