Growth and decline of arboreal fungi that prey on Bursaphelenchus xylophilus and their predation rate

2022-04-17HaixiaoZhangZhiyanWeiXuefengLiu

Haixiao Zhang·Zhiyan Wei·Xuefeng Liu·

Jie Zhang2·Guiping Diao1

Abstract Pine wilt disease caused by pine wood nematodes is a deadly disease of the genus Pinus requiring strong quarantine measures. Since its discovery, it has been widely distributed throughout the world. China is one of the countries with a severe rate of infections due to its abundant pine resources. In this study, nematode-trapping fungi were collected from pine trees in Ninghai City, Zhejiang Province, which is the key area of pine wilt control in February, May, September, October and November. The results showed that nematode- trapping fungi of pine are abundant, especially the number and species detected in each month and are quite different; species of fungi in July, September and November were more numerous and had higher separation rates. The dominant species in November was

Keywords Arboreal Bursaphelenchus xylophilustrapping fungi·Distribution·Dominant species·Culture conditions·Rate of predation

Introduction

Pine wilt disease is a lethal disease that infects pine species worldwide, and is the direct cause of death of millions of pines in south-east Asia, mainly Japan, China and Korea. The disease is also found in Portugal, Greece, the United States, Mexico and Canada (Zhu 1995; Chen et al. 2004; Bonifácio et al. 2014; Proença et al. 2017). According to the latest report in 2019, pine wilt disease in China is rapidly spreading westward and northward (Cheng et al. 2015), spreading from Liangshan in the westernmost part of Sichuan province and multiple counties in the northernmost part of Liaoning to 17 other provinces, contaminating pines in scenic and ecologically important areas across the country (Zhang et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2013). The epidemic prevention area based on the limit of annual average temperatures above 10 °C proposed by traditional theory was broken, and new species were discovered such asMonochamus saltuariusGebler. (Han et al. 2010). Hazard targets have been expanded fromPinusmassonianaLamb. andPinus thunbergiiParl. species to species such asPinus koraiensisSieb. et Zucc., threatening the health of nearly 60 million hectares of pine resources (Jiang 2019). Therefore, options for the control of pine wilt disease are urgently needed. However, due to toxicity, cost and application restrictions of chemicals, there is no chemical available forB. xylophilusmanagement (Douda et al. 2015). Biological control options like arboreal nematode-trapping fungi can be attractive and effective. Previously, we have studied and reported on the classification of arboreal nematode-trapping fungi (Zhang et al. 2020). These fungi are of considerable significance for the biological control of pine wood nematodes (Wei et al. 2010). Due to the characteristics of regular fungal growth and decline, the colonization of different species of dendrocola nematode-trapping fungi involves understanding spatial and temporal population fluctuate (Eckhardt et al. 2009). Different strains show different dynamic changes under similar environmental conditions (Kim et al. 1997). For example, in the soil, nematode-trapping fungi grow and decline with seasonal changes (Prejs 1993; Persmark et al. 1996). In a number of susceptible and infectious areas in China, continuous sampling is carried out throughout the year. Healthy and susceptible trees are studied and samples are taken from the trunk horizontally and vertically and soil samples are separated (Persmark and Jansson 1997). In 2020, six species of arborealB. xylophilus-trapping fungi were isolated and identified in the pine wood nematode occurrence area of Haining City, Zhejiang Province (Zhang et al. 2020). Based on this study, we decided to study the source, distribution and predation rates of four species ofB. xylophilus- trapping fungi obtained from tree trunks under different cultural conditions. The study of these factors may be an important steeping stone in the search of biological control options for the pine wood nematode worldwide.

Materials and methods

Sample collection method

Pine wilt disease infected wood, and similar material from healthy trees were collected in the pine wilt disease epidemic area. Three to four infected trees and one healthy tree were randomly selected. From bottom to top of the trunk, a 3-cm disc was removed every 1 m; a smaller disc was removed from the first side branch at the junction with the trunk, and a similar disc from every other year branches; all discs were numbered as to location.

Location: Ninghai City, Zhejiang province.

Sample treatment

Wood samples were divided into bark and xylem, and the bark divided into cork, cork cambium, and phelloderm, and the wood divided into sapwood and heartwood (Myers 1988; Son et al. 2010). If there were blue-stain in the samples, they were marked. Shoot samples were divided into the cork cambium and xylem (Wang et al. 2005).

The samples were collected as follows: 57 in February, 52 in May, 40 in July, 37 in September and 56 in November, for a total of 242. Samples were cultured according to the different parts, the xylem of each sample was cut into pieces 1-2 cm × 3-5 cm, and 8-10 pieces placed in each culture dish. The bark was cut into sections and spread in two rows on a CMA medium. Mud from the bark, sawdust, and tunnels were also scattered in two rows on the CMA medium. The above was repeated three times. The nematode suspension of approximately 5000 nematodes was added to each dish, the number and the date of separation marked, and incubated at room temperature. After four weeks, the type and quantity of predatory fungi induced was observed under a dissecting microscope.

Saprophytic nematodes (Panagrellus rediviusL.) were inoculated onto an oatmeal medium and cultivated at 25 °C as bait for nematodes. After the nematodes emerged, they were flushed with sterile water using a Baermann funnel and diluted to a nematode suspension with a concentration of 500 mL-1(Baermann 1917).

For purification of predatory nematode fungi, the cultures were examined under a dissecting microscope under aseptic conditions. When there was a predatory nematode fungus present, a sterile extra-fine bamboo stick was used to remove it, and a single conidia transferred to a 60 mm petri dish containing CMA medium, sealed with parafilm, numbered and purified. It was then incubated in darkness at 25 °C for one to two weeks.

For the preservation of strains, a small piece of medium with colonies was removed and placed into a sterile centrifuge tube, sealed and labeled for each strain. For subsequent preservation, the identified specimens were stored in finger-shaped tubes containing CMA medium to extend the preservation time.

Under aseptic conditions, in a purely cultured nematodepredatory fungus plate, a 1- 2 × 0.5 cm agar block was cut, and a 1 ml of nematode suspension placed onto the culture dish where there was no medium. A 0.5 ml drop on the surface of the culture medium induced the production of predatory organs. After 48 h, the structural characteristics of the nematode-trapping fungus were observed under a microscope. The surface of the colony was placed on a slide with transparent tape and a drop of lactophenol oil cotton blue dye solution placed on the slide. A drop of cotton blue dye solution was placed on the glass slide for one to two minutes. Morphology was observed under a microscope and photographed. For the separation, identification, and purification of strains see Hyde et al. (2014) and Zhang et al. (2020).

For the calculation of the separation rate,

Determination of predation rate of arborealB. xylophilus-trapping fungi

The fungi tested wereArthrobotrys dendroides,A. musiformis,A. cladodesandA. oligospora, the strains isolated from the collected samples (Zhang et al. 2020). The four strains were put into PDA (potato-dextrose-agar), LPDA (lack-patato-dextrose-agar), CMA (corn-meat-agar), and LCMA (lack corn-meat-agar) media, respectively, and repeated three times. The cultures were put into a 25 °C incubator for 7-8 days. When the colony was full, the whole dish is saved. PDA medium was prepared with 200 g of potato, 1000 mL of distilled water, and 15 g of agar; LPDA medium prepared with 100 g of potato, 1000 mL of distilled water, and 15 g of agar. CMA medium was prepared with 20 g of corn flour, 1000 mL of distilled water and 15 g of agar, and LCMA medium prepared with 10 g of corn flour, 1000 mL of distilled water and 15 g of agar.

A Baermann (1917) funnel was used to wash theB. xylophiluscultured inPestalotiopsissp. to a small test tube. A 0.1 mL droplet of the nematode solution was placed on a slide and the number of living nematodes observed under an optical microscope. There were 96 living worms in a 0.1 mL droplet of the nematode. Following this, the test tube mouth was flushed up and put into a small triangle bottle to make the nematode precipitate. When the nematode completely precipitates to the bottom of the test tube, the supernatant was extracted with a pipette, and sterile water added three times with the same method. A 10 mL sterile water was added and the pipette used to divide the nematode precipitate into 25 dishes. A 0.4 mL of mixed pine wood nematode suspension was added to the culture dish of the nematode prey.

Effects of different culture conditions on predation

With the CMA medium, there were two dishes ofA. cladodesand three ofA. musiformis; there were three dishes ofA. musiformison LCMA medium; three dishes ofA. cladodesand three ofA. dendroideson the PDA medium; on the LPDA medium, there were three dishes ofA. cladodes, three ofA. dendroidesand three ofA. musiformis, a total of 23 dishes. At 48 h and 72 h, the number of nematodes caught, the number of living nematodes, the number of dead nematodes that were not completely degraded, and the number of eggs were observed under the microscope. When observing, the dish was divided into eight small areas with a marking pen to avoid repeated counting.

The method of adding nematode suspension was the same as for the preparation and dropping ofB. xylophilussuspension. There were six dishes on CMA, six on LCMA and six on PDA. There were about 60 live worms in every 0.1 mL, 0.2 mL in every dish. After dropping the suspension, three dishes of each strain were placed into a 20 °C incubator, and the other part into a 25 °C incubator. After 48 h, the predation rate was tested as in the previous paragraph.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS version 26.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Distribution and seasonal variation of arborealB. xylophilus-trapping fungi on trees

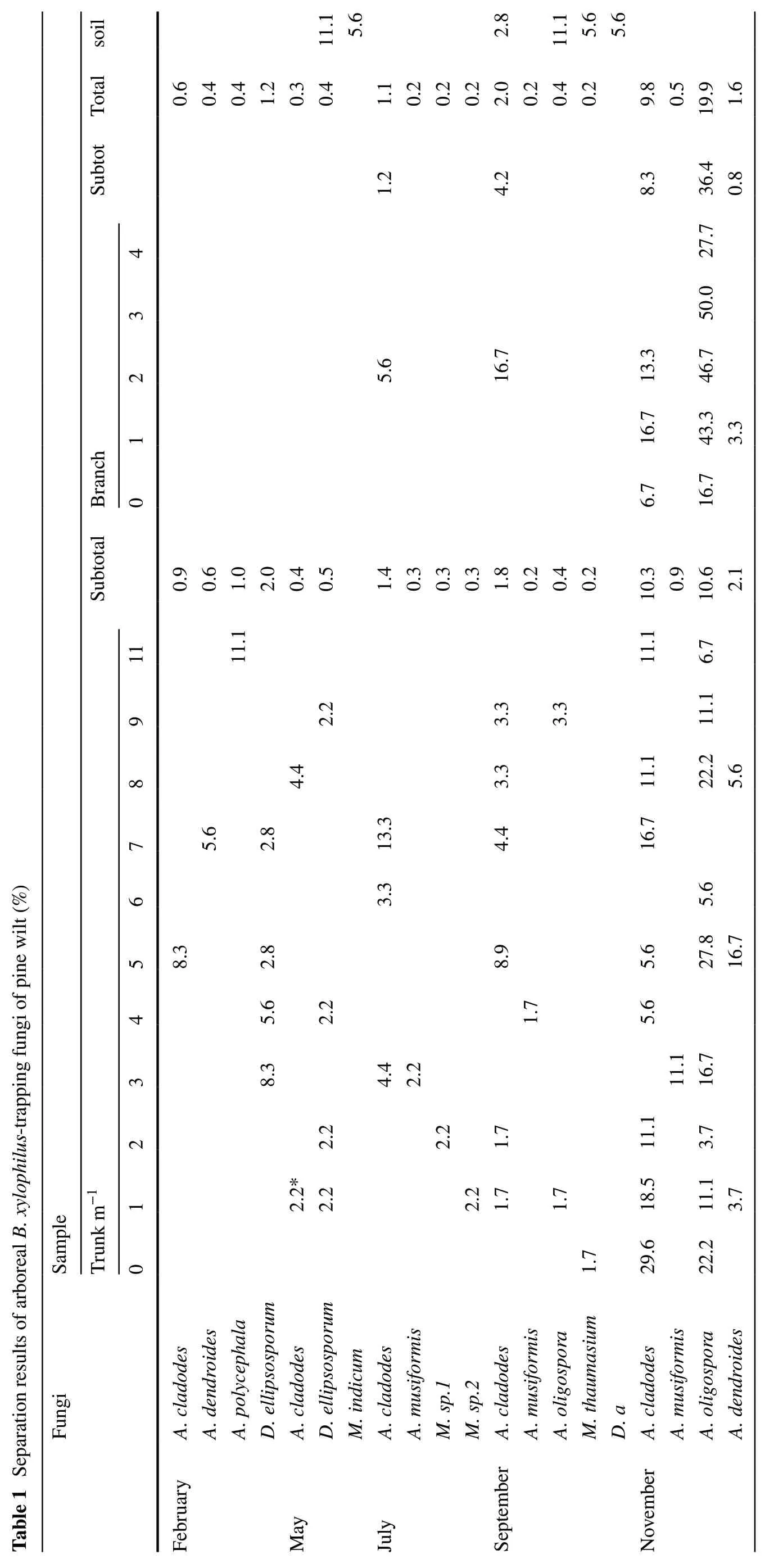

Seasonal changes and the distribution of arboreal predatoryB. xylophilusfungi on the tree reflect the growth and decline of predatory nematode fungi. Arboreal predatoryB. xylophilusfungi are distributed in various parts of the pine wood nematode wilt disease, and on stems 1 m above the ground were five species, followed by four species at 2 m (Table 1). At seven m above ground, there was only one species.

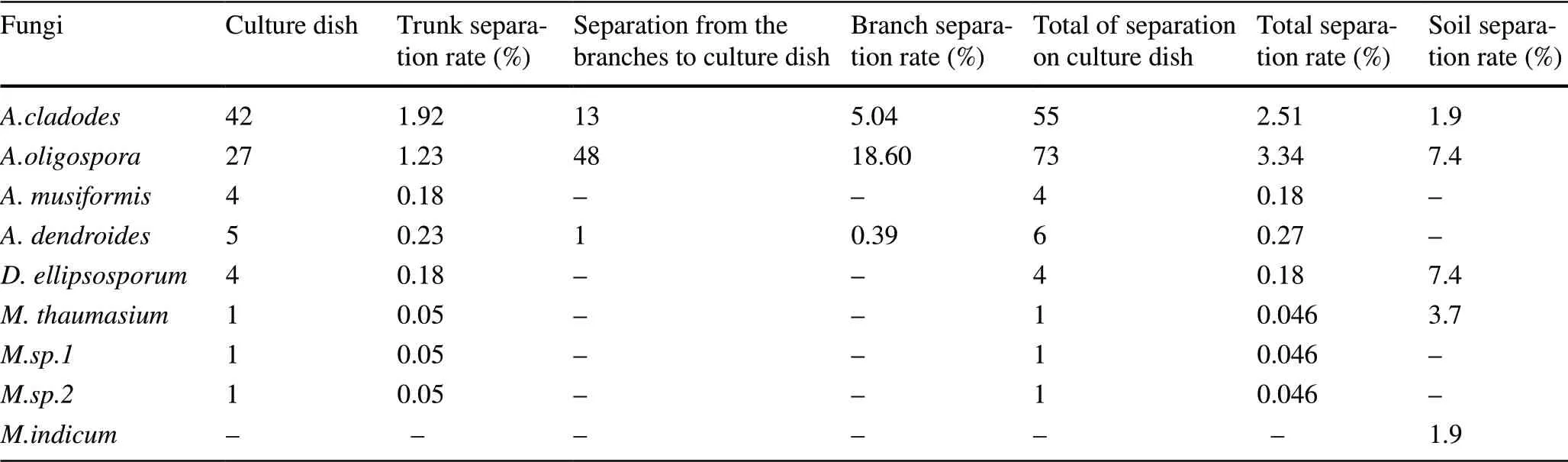

From Tables 1 and 2, it can be seen thatArthrobotrys oligosporaandArthrobotrys cladodeswere the dominant species. Their separation rates were 3.3% and 2.5%, respectively; the separation rates of other fungi were below 0.3%.A. cladodescan be separated at almost all heights of a diseased tree, and the highest separation rate was between the trunk and the ground, which was 29.6% in November. The separation rate ofA. cladodeson the trunk was lower than on the branches. They were mainly concentrated on branches closer to the trunk and could be separated every month, and increased with the month. The highest separation rate was 10.3% in November.A. oligosporawas isolated only in September and November, with more being in November when it could be separated from almost all parts of the tree. The separation rate was up to 27.8% at 5 m. The separation rate on the branches it is higher than on the trunk and it is found in all segments, the highest being 50.0% in the third segment closest to the trunk. Dactylellina ellipsosporum was isolated only at 1-9 m in February and May, mostly concentrated in the middle of the trunk and closer to the ground, and was not separated in other months and locations. Arthrobotrys musiformis was isolated in all months except May but appeared in limited locations at 3 m in July, 4 m in September and 3 m in November. A. dendroides separated at 1 m, 5 m and 8 m in November. Monacrosporium thaumasium and M.sp.1, M.sp.2 are rare species and are distributed below 2 m. Three species of B. xylophilustrapping fungi were isolated on the branches, the dominant species being A. oligospora and A. cladodes, with separation rates of 18.6% and 5.0%, respectively, and A. dendroides only 0.4%.

3.3 环境干预 病房走廊墙上张贴臂丛神经损伤后康复锻炼的照片,每周1次由责任护士为患者作康复锻炼的示范,使患者了解手部锻炼的重要性。

Table 2 Results of arboreal B. xylophilus-trapping fungi on pine wood

5.62.85.6 soil 11.1 11.15.6 0.60.40.41.20.30.41.10.20.20.22.00.20.40.29.80.51.6 Total 19.9 Subtot 1.24.28.336.4 0.8 4 27.7 3 50.0 2 5.616.7 13.3 46.7 Branch 116.7 43.3 3.3 0 6.716.7 0.60.91.02.00.40.51.40.30.30.31.80.20.40.20.92.1 Subtotal 10.3 10.6 1111.1 11.1 6.7 9 2.23.33.311.1 8 4.43.311.1 22.2 5.6 7 2.813.3 4.4 5.616.7 Table 1 Separation results of arboreal B. xylophilus-trapping fungi of pine wilt (%)63.35.6 58.32.88.95.627.8 16.7 4 5.62.21.75.6 3 8.34.42.211.1 16.7 2 2.22.21.711.1 3.7 1 2.2*2.22.21.71.718.5 11.1 3.7 Sample Trunk m-1 0 1.729.6 22.2 Fungi A. cladodes A. dendroides A. polycephala D. ellipsosporum A. cladodes D. ellipsosporum M. indicum A. cladodes A. musiformis M. sp.1 M. sp.2 A. cladodes A. musiformis A. oligospora M. thaumasium D. a A. cladodes A. musiformis A. oligospora A. dendroides February May July September November

Comparing the arborealB. xylophilus-trapping fungi in May and September with the predatory nematode fungi in the soil, the separation rate in the soil was higher than in the tree and the isolated species were closer, indicating thatB. xylophilus-trapping fungi and soil predatoryB. xylophilusfungi have a large correlation in a certain range. The dominant species of the two are different. The dominant species in soil wasD. ellipsosporumin May andA. oligosporain September with a separation rate of 11.1%; the dominant species in May wasD. ellipsosporum, and in September I wasA. cladodes, with lower separation rates of 0.4% and 1.1%, respectively. The number and species of predatoryB. xylophilusdetected in each month varied widely. Among them, the separation rate of the four strains in July, September, and November was relatively high, while there were fewer species in May and the separation rates were relatively low.A. oligosporawas not only distributed on tree trunks, but also in the special environment of the tunnel of longicorn, and also in the soil.B. xylophiluspredators were isolated from heavier samples of blue stained wood but the correlation was not strong.

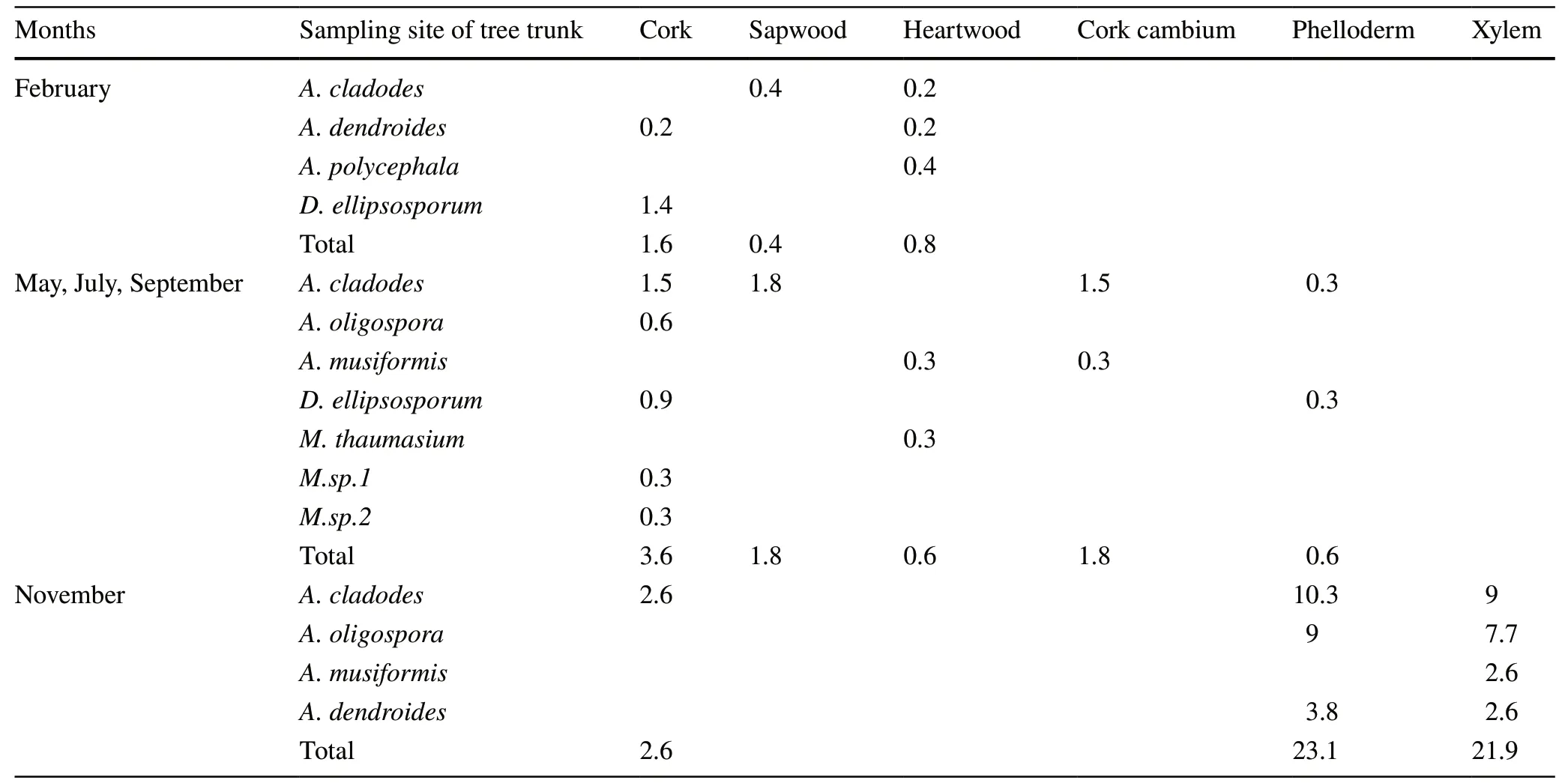

Horizontal distribution and seasonal variation of arborealB. xylophilus-trapping fungi on diseased trees

The cross section of pine wood nematode wilt disease has more predatoryB. xylophilusfungi on the bark than on the xylem (Table 3). In November, there were more phelloderm than cork fungi, and other months were contrary to November with fungi on more sapwood than heartwood.A. cladodeswas the dominant species, especially in November in the cork, phelloderm and xylem; in other months, [except fungi in the heartwood is not distributed, all parts are distributed,] sapwood up to 1.8%. In November, the subdominant species wasA. oligospora, which was concentrated on the phelloderm and xylem, and in the other months was only distributed on the cork. In May, July, and September, the subdominant species wasD. ellipsosporum, which was mainly distributed on the cork and phelloderm layer, and not distributed on the wood.M. thaumasiumand two other species still need to be identified and could be rare species.

Effect of time on predation activity

The time of interaction betweenB. xylophiluspredators and pine wood nematodes directly influences the effect of predation. From Tables 4, 5 and 6, the predation rate after 48 h byA cladodeswas 69.0%-82.4%, with an average of 75.0% and after 72 h it was 46.8%-87.3%, with an average of 83.3%. The predation rate after 48 h byA. dendroideswas 42.7%-81.1%, with an average of 63.0% and after 72 h I was 44.3%-87.5%, with an average of 67.1%. The predation rate after 48 h byA. musiformiswas 25.5%-77.8%, with an

Table 3 Horizontal distribution of arboreal B. xylophilus-trapping fungi (%)

Table 4 Determination of a 48 h predation rate

Table 5 Determination of a 72 h predation rate

Table 6 Average predation rate of arboreal B. xylophilustrapping in different time

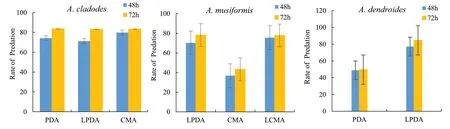

Effect of different culture medium on predation activity

The growth and development of organisms are inseparable from nutrition and the predation of pine wood nematode fungi are subject to this. The order of predation after 72 h ofA. cladodesis PDA > CMA > LPDA (Table 6, Fig. 1). The highest predation rate was 83.6% in PDA, 83.3% in CMA and 83.1% in LPDA. Their predation rate is high and their activity good; there was no significant difference between the media.A. cladodeshas better predation activity in both the nutrient rich medium and the nutrient weak medium, i.e., there is less nutrient demand.

Fig. 1 Effect of different media on the predation rate of arboreal B. xylophilus-trapping, Note: P < 0.05 means difference is significant

The order ofA. musiformispredation rate after 72 h was LPDA > LCMA > CMA, with the highest rate of 78.2% in the LPDA medium and 77.8% in the LCMA medium, which are similar, and in CMA, the predation rate was low at 43.3%. The differences in predation rates indicated that predation activity was greatly affected by nutrient richness in the culture medium, and the predation rate of CMA was too rich.A. musiformisis more suitable for predation on pine wood nematodes under the condition of LPDA and LCMA media.

The predation rate ofA. dendroidesafter 72 h in PDA was 49.6%, while in LPDA it was 84.5%, indicating that the nutrient content in PDA medium was too high and inhibited predation activity. The nutrient levels in the LPDA medium were relatively moderate and improved predation activity.

The predation rates of the three species of pine wood nematode were different. From the average predation rate after 72 h, the ranking wasA. cladodes>A. dendroides>A. musiformis. The highest was 84.5% on PDA and the lowest was on CMA.

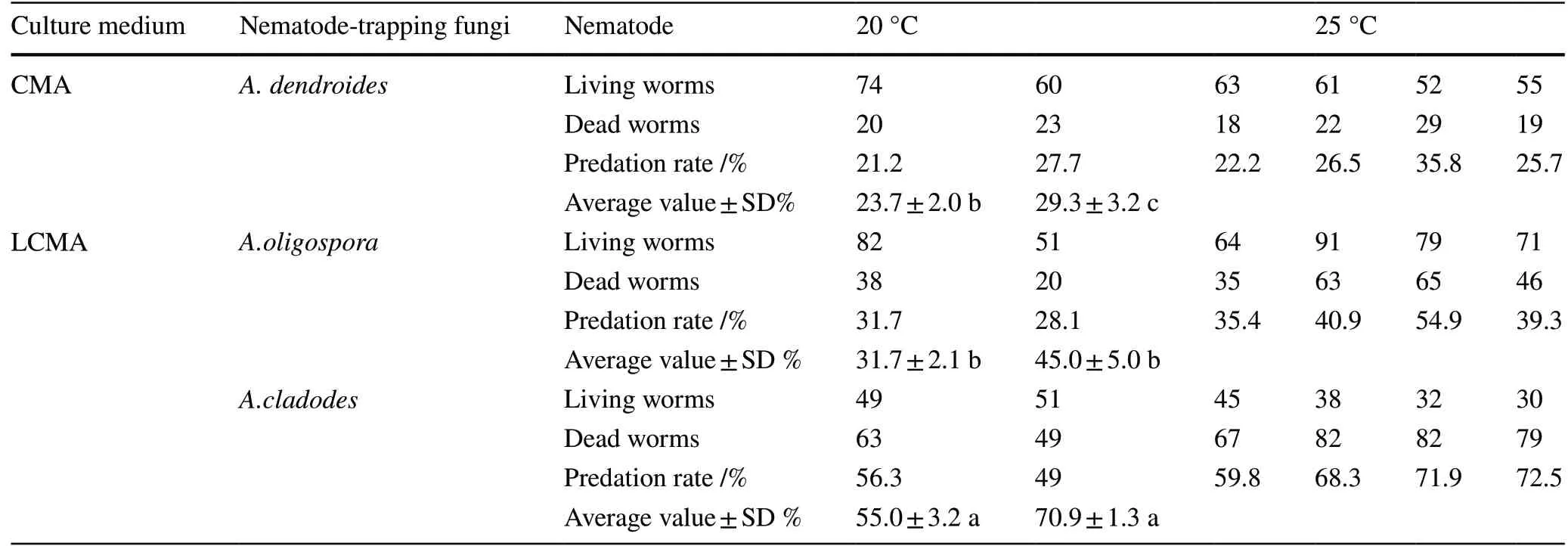

Effect of temperature on predation activity

Temperature is an important factor affecting the activity of pine wood nematodes. The predation rate byA. dendroidesafter 48 h on the CMA medium was 29.3% at 25 °C and 23.7% at 20 °C, 5.8% points lower (Table 7). On the LCMA medium, the predation rate ofA. oligosporaafter 48 h was 45.0% at 25 °C and 31.7% at 20 °C. On LCMA medium, the predation rate ofA. cladodesafter 48 h was 70.9% at 25 °C and 55.0% at 20 °C.

Table 7 Predation rate under different temperatures

Discussion

On diseased trees of pine wood nematode fusarium wilt,A. cladodeswas widely distributed (Sriwati et al. 2007) with a high separation rate, and was more suitable for the environment of theP. thunbergiiParl. Therefore,A. cladodeshas a large potential biological control value. The predator is a three-dimensional fungus net (Gray 1987). This study showed that the predators ofB. xylophiluscould only be isolated from diseased trees, indicating that these fungi are strongly dependent on nematodes. There are more predatoryB. xylophilusfungi on the bark than on the xylem which may be related to the biological characteristics of supplementary nutrition and spawning ofMonochamus alternatusHope (Teale et al. 2011). The activity ofM. alternatusgradually increases from the bark to the xylem, and the nematodes also carried deeper (Zhang et al. 2008). It stays in the bark longer than in the xylem, which further indicates that the predation ofB. xylophilusfungi depend on pine wood.

Almost all the predator nematodes reported have been isolated from soil and water (Back et al. 2002; Niu and Zhang 2011; Nordbring et al. 2011; Guillermo and Hsueh 2018). There are very few species isolated from pine species, and records includeA. oligosporaandD. ellipsospora. Compared with the predatoryB. xylophilusfungi in the soil, the pine wood nematodeFusarium oxysporumSchltdl. has fewer host species of trees and a lower separation rate, but has a strong correlation, so predation on trees is not excluded.B. xylophilus-trapping fungi may originate from soil also has a strong predatory effect on pine wood nematodes (Noweer 2017). Research by Renčo et al. (2010) shows that the number of nematodes in soil was the lowest from July to October at Nemšová (Slovak Republic). This is consistent with our research results, both in terms of species and quantity; predatory pine wood nematode fungi isolated from the soil was highest from July to September. Other scholars have also isolated a variety of nematode-predator fungi in aquatic environments but there are differences with the species we isolated. For example,A. vermicolawas isolated in water (Zhang et al. 2012) but we did not find it on trunks. Therefore, nematode-predatory fungi on the tree trunks are possibly from the soil. In addition, related studies have shown that the seasonal change in the number of nematode-preying fungi is linearly related to temperature but S-shaped with the total number of nematodes and has no significant correlation with soil moisture and the number of parasitic nematodes (Miao and Liu 2003). In this paper, the sampling site was in eastern China. Due to temperature changes in other epidemic areas, the types and numbers of arboreal predator pine wood nematode fungi may also change, which is the focus of future studies.

Judging from current research, species of arboreal predatory nematode fungi are abundant and have considerable potential (Yang et al. 2007). Pine wood nematode fusarium wilt is often accompanied by blue discoloration of the wood (Hofstetter et al. 2015), although predator nematode fungi are also isolated from samples with blue discoloration (Morris and Hajek 2014), but there is little difference compared with clear wood. From the separation results, arboreal predation nematode fungi are also abundant. How to make good use of these resources to mitigate and control the damage by pine wood nematode fusarium should be the focus of future research (Buckley et al. 2010). Areas that require further research include nematode predation processing formulations, release technologies, how to colonize and expand the colony after entering the tree (Liu et al. 2014; Aram and Rizzo 2018), and the continuous control of pine wood nematodes.

Pine wilt caused by pine wood nematodes is a global devastating disease (Silva et al. 2013), but soil application of nematophagous fungi for the biological control of plantparasitic nematodes often fails (Monfort et al. 2006). The discovery of tree-feeding nematodes (Zhang et al. 2020) and the predation rate of pine wood nematodes will improve prevention and control. In this study, when testing the predation rate of predatory nematode fungi, we found that mature nematodes on the culture medium spawn large numbers of eggs. The emergence of new individuals directly affects the measurement of the predation rate and evaluation of predation activity, making the observed values low. For example, during the period from 48 to 72 h, the number of live pine wood nematodes inA. dendroidescultivated in PDA reached 86.0%. Therefore, how to reduce which error caused by the amount of eggs in the research process becomes difficult. Predation rate data from different media indicated that predation activity is greatly affected by the nutrient composition of the medium, and different fungal strains have different nutrient requirements (Imfeld et al. 2013). The predation rates of three species of pine wood nematode fungi on LPDA were relatively close, each more than 78.2%, which is a medium with wide adaptability and good effect. While LCMA supported only one kind of fungus successfully, the amount of inoculation should also be increased to further determine whether it can successfully cultivate other fungi. In this study, four different predatory nematode fungi were inoculated on four different media, but the medium containingA. oligosporesdid not provide valid data. This should be re-examined. In this study, under different culturing temperatures, within a certain temperature range as the temperature increased, the predation rate of the nematode fungi increased and the predation activity was enhanced. Research has shown that the optimal medium temperature was 15-35 °C (Li et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2019), and researcher was confirmed that the optimal temperature for nematode development is 20-25 °C (Liu and Zhang 2013). Too high or too low a temperature will affect fungal activity, hence in this study, two temperature gradients were selected.

Most studies on the growth and decline of nematodepreying fungi are concentrated in the soil and aquatic environments. At present, pine wood nematodes are a serious disease that is difficult to prevent and to control on pine species globally. However, there are few reports on the survival of pine wood nematode- trapping fungi on tree trunks. This research adds information to domestic and international studies on the seasonal growth and decline of the predation of pine wood nematodes on tree trunks and verifies their predation effects. It provides a new theoretical basis and supporting data for the prevention and control of pine wood nematodes and new ideas for biological control.

Conclusions

The distribution of arborealBursaphelenchus xylophilustrapping fungi are present on the diseased wood ofPinus.There was no distribution of arborealB. xylophilus-trapping fungi on healthy black pine; the fungi isolated on the diseased wood were also distributed in soil. Therefore, arborealB. xylophilus-trapping fungi may have a dependent relationship with soil predatory nematode fungi. ArborealB. xylophilus-trapping fungi have seasonal changes and species vary from spring to autumn. The species and separation rates gradually increase with the season, peaking in November. OnB. xylophilusdiseased trees,A. cladodeswas the dominant species, widely distributed with a high separation rate and more adaptable to the environment on black pine. It has considerable potential value in biological control.

The arborealB. xylophilus-trapping fungi selected in this study have a good predation effect on pine wood nematodes, and the length of time that the fungi interact with the pine wood nematodes, the type of medium, and the culture temperature, will directly affect the predation rate. A. dendroideshad the highest predation rate of 84.5% on LPDA at 72 h, with good development potential. The predation rates of three species of pine wood nematode fungi on LPDA are relatively close and above 78.2%, which indicates that LPDA is a medium with wide adaptability. Within a specific temperature range, as the temperature increases, the predation rate of the nematode fungi increase and the predation activity increases.

Author’s contributionsXFL provided the initial idea for the study, HXZ and GPD analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. JZ oversaw the project. ZYW and HXZ assisted with the research. XFL and GPD directed the research. JZ and XFL funded the research. All authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

猜你喜欢

杂志排行

Journal of Forestry Research的其它文章

- Molecular characterization and functional analysis of daf‑8 in the pinewood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus

- Modeling habitat suitability and utilization of the last surviving populations of fallow deer (Dama dama Linnaeus, 1758)

- The identification and pathogenicity of Fusarium oxysporum causing acacia seedling wilt disease

- Volatile metabolites of willows determining host discrimination by adult Plagiodera versicolora

- Soil ecosystem changes by vegetation on old-field sites over five decades in the Brazilian Atlantic forest

- Response of soil respiration to environmental and photosynthetic factors in different subalpine forest-cover types in a loess alpine hilly region