家庭读写环境与儿童接受性词汇发展关系的元分析

2022-03-15刘海丹李敏谊

刘海丹 李敏谊

·元分析(Meta-Analysis)·

家庭读写环境与儿童接受性词汇发展关系的元分析

刘海丹1李敏谊2

(1陕西师范大学教育学部, 西安 710062) (2北京师范大学教育学部, 北京 100875)

家庭读写环境(home literacy environment, HLE)与儿童接受性词汇(receptive vocabulary)发展的关系一直备受关注, 但HLE内涵不清、各指标效应值强度不明, 以及近年来两者关系差别较大等问题极大地限制了人们对该领域的认识。本文运用元分析技术对近30年国内外84篇相关实证研究进行分析。结果显示:HLE与儿童接受性词汇发展为中等程度正相关(= 0.31)。针对年代、文化背景、儿童年龄以及测量方法的调节效应检验表明:HLE效应值随年代发展显著降低, 但其核心指标亲子阅读频率的效应值基本稳定; 评估HLE的问卷法和现场观察法效应值无差异, 但评估亲子阅读频率的书目清单法效应值显著高于问卷法。未见文化背景和儿童年龄的显著调节作用, 原因值得进一步探究。后续研究应完善HLE的概念框架, 更关注社会经济及文化视角下的概念建构以及测量改进。

家庭读写环境, 亲子阅读, 接受性词汇, 元分析

1 引言

家庭读写环境(home literacy environment, HLE)系指家庭中能够影响儿童读写能力发展的资源和活动(Burgess et al., 2002; Puglisi et al., 2017)。从上世纪60年代至今, 大量研究证明HLE是影响儿童语言, 尤其是接受性词汇(receptive vocabulary)发展的重要变量(Griffin & Morrison, 1997; Roberts et al., 2005; Lohndorf et al., 2018)。作为儿童起步较早的能力, 接受性词汇于婴儿期开始发展, 在学龄前增长尤为迅速(Farkas & Beron, 2004)。这期间, HLE对儿童日积月累的影响发挥了非常关键的作用。研究表明, 来自不同家庭的儿童在3岁时彼此间就已经形成了巨大的词汇鸿沟(Hart & Risley, 1995; Fernald et al., 2013),极大地影响到当前及未来的读写能力和学业成就(Roth et al., 2002; Sénéchal, 2006)。因此, 关注HLE对儿童接受性词汇发展的作用有重要意义。

虽然国内外有关HLE与儿童接受性词汇发展关系的研究数量庞大, 但以下问题尚不明朗:一是HLE到底包含哪些指标, 分别与儿童接受性词汇发展相关强度如何, 且彼此间有何差异?二是近年来聚焦两者关联强度的研究结果出现较大分歧, 例如, 相关系数从0.63 (Griffin & Morrison, 1997)下降到0.35 (Schmerse et al., 2018), 甚至低至0.11 (Gonzalez et al., 2017), 究竟有哪些变量在发挥调节作用?鉴于元分析是对“相同目的”且“相互独立”的多个研究结果进行定量统计的综合分析方法(Camisón-Zornoz et al., 2004), 能从更宏观的角度整合该领域的结果从而得出更普遍和准确的结论, 因此有必要借助元分析探究上述问题。

关于两者关系的国内外元分析较少且存在一定的局限性。首先, 未全面分析HLE指标。例如, 两项元分析仅关注了亲子阅读频率与儿童语言发展的关系(Bus et al., 1995; Mol & Bus, 2011)。Dong等人(2020)虽聚焦HLE整体, 但采用的四维度划分方式有争议, 如父母受教育程度在多项研究中属于家庭社会经济地位(social economic status, SES)的范畴。此外, 也未回应不同研究中HLE指标出入较大的问题, 因此读者难以对HLE有全面了解。其次, 对HLE这一概念认识不足, 多以静态眼光分析HLE与儿童语言发展的关系, 未意识到HLE的历时变迁(Hiebert, 2015)、文化背景(Shu et al., 2002; 李燕芳, 董奇, 2004)、儿童年龄(Inoue et al., 2018 )以及测量方法(Wang, 2015)等变量对二者关系的潜在调节作用。再者, 还尚未有元分析将儿童接受性词汇发展作为结果变量, 探究其与HLE的关系。

因此, 本研究采取元分析方法, 系统分析国内外1990~2021年间HLE与儿童接受性词汇发展关系的实证研究, 在深入剖析HLE内涵的基础上, 探究两者相关程度及调节变量, 以期丰富HLE概念本身及其与儿童接受性词汇发展关系的研究图谱, 为未来研究提供依据和方向。

1.1 HLE的内涵与测量

从上世纪60年代Durkin (1966)率先关注HLE至今, 虽然相关研究众多, 但对HLE始终没有统一的定义。起初重点关注亲子阅读, 后来随着实证研究的推进及元分析的争鸣(Bus et al., 1995; Scarborough & Dobrich, 1994), 研究者们认为应当延展HLE的内涵。总体有两种界定取向:(1)人类发展生态学理论视角。该视角认为HLE是家庭中对儿童语言发展产生作用的各类要素。研究者根据家庭环境对儿童发展的作用路径, 划分为三个方面(Leichter, 1984; Griffin & Morrison, 1997; Whitehurst & Lonigan, 1998):一是家庭读写资源, 指家庭中支持读写活动开展的各类物质资源, 如藏书、玩具:二是动机氛围, 指家庭中父母对读写活动价值的认识及重视程度, 如父母对儿童读写活动重要性的认识、自身读写习惯; 三是各类读写活动, 如亲子阅读、去图书馆, 还有研究者根据活动开展方式, 划分为亲子共同参与的读写活动、儿童独立的读写活动, 以及儿童观察成人的读写行为三类(Teale & Sulzby, 1986)。上述HLE框架使用范围最广, 虽然也有人认为应纳入父母受教育程度(Dong et al., 2020), 但大部分研究还是将其归于SES的范畴。(2)互动理论视角。该视角认为HLE是儿童在家庭中经历的以人与人之间的交互为载体的各类活动。这一视角下比较有代表性的是Sénéchal等人(1998) 提出的“家庭读写模型(home literacy model)”。由于年代较早, 该模型重点关注的是围绕印刷品(print)的家庭读写活动, 将其划分为非正式读写活动(informal literacy activity)和正式读写活动(formal literacy activity)。非正式读写活动指的是关注印刷品所承载的信息、偶尔或很少关注其书面语言的活动, 如听故事、讨论故事情节; 正式读写活动则以印刷品的书面语言为学习重点, 例如认字、书写。研究表明, 家庭中这两类读写活动呈现弱相关, 并分别指向儿童不同的语言能力(Hamilton et al., 2016; Manolitsis et al., 2011; Sénéchal, 2006)。总体来看, 虽然上述两种理论界定角度不同, 但彼此重合且互相补充, 共同揭示了HLE的复杂本质, 并且随着HLE研究的深入, 互动理论视角越来越受到人们关注。

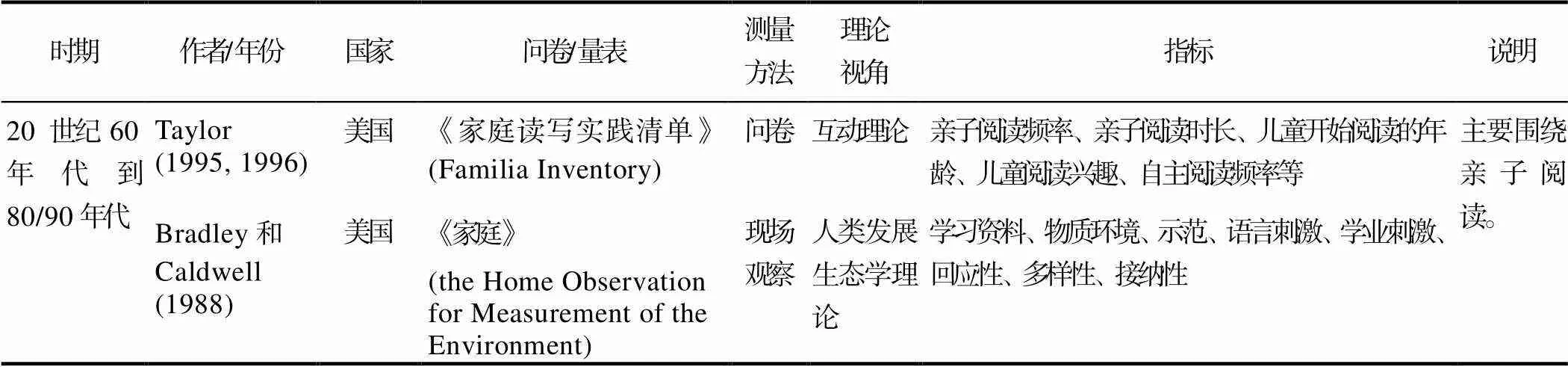

对HLE的测量工具进行系统梳理(见表1)发现, HLE的问卷数量众多、指标繁杂, 几乎各研究中所采用的问卷指标或权重均有差异, 但总体上有如下特点:(1)横向来看。基于两种理论视角研发的问卷并存, 偶尔也有两种理论的交融。研究者的普遍做法是, 总体以人类发展生态学理论视角下的问卷为主, 在“读写活动”中融合互动理论视角下的相关指标。HLE代表性问卷有:《石溪家庭阅读调查表》(Stony Brook Family Reading Survey) (Whitehurst, 1993)、《家庭读写环境量表》(Family Literacy Environment Scale) (Griffin & Morrison, 1997)、《家庭学习环境概况核查》(Home Learning Environment Profile) (Heath et al., 1993)、《斯帝佩克家庭学习活动调查表》(Stipek Home Learning Activities) (Stipek et al., 1992)。(2)纵向来看。上世纪八九十年代确立了HLE的基本框架并产生了一系列代表性问卷, 后续研究则在此基础上改编或参照自编。随时间推移主要有两点变化:其一是非正式读写活动日渐丰富。起初主要是围绕印刷品(主要是书)的亲子阅读, 后逐渐延伸到游戏活动、看电视等家庭内部活动, 以及去博物馆、艺术展等外出活动(Kirby& Hogan, 2008)。近期, Krijnen等人(2020)明确指出了“家庭读写模型”的局限性, 对其进行了系统修正, 极大地扩展了读写活动的范围。其二是尝试不同的界定方法, 例如分为主动读写环境和被动读写环境(Burgess et al., 2002; Baroody & Diamond, 2012), 但所涉指标变化不大。(3)关于亲子互动质量的问题。诸多研究者早就关注到各类读写活动中亲子互动质量的重要性(Pellegrini et al., 1995), 但由于直接测量难度大, 问卷很少涉及, 只在通过现场观察进行评估的《家庭》量表 (The Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment, HOME) (Bradley&Caldwell, 1988)中有所体现。

表1 HLE评估问卷及量表

续表

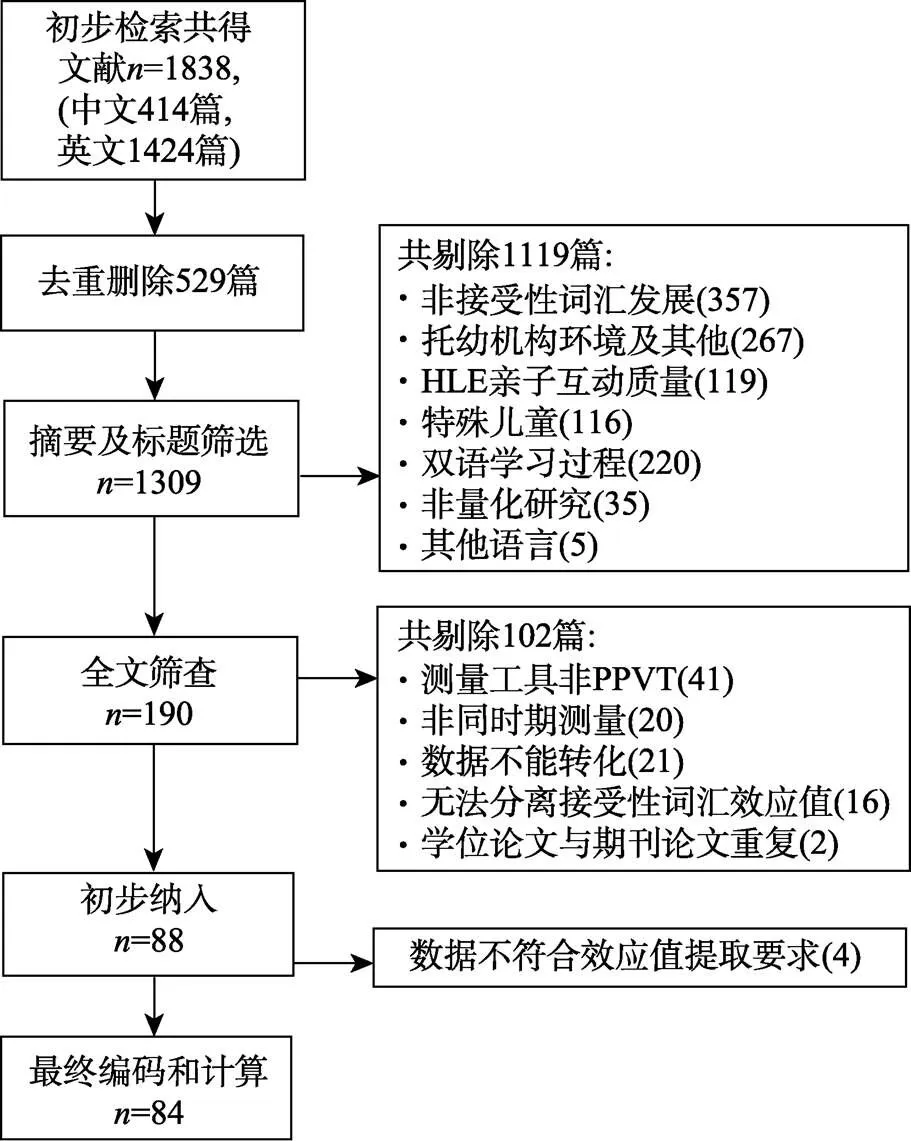

从前文可见, 虽然HLE的评估方法多样, 但基于人类发展生态学理论的三方面结构是主流框架, 因此本研究亦借用此结构分析HLE并构建效应值提取框架。

1.2 接受性词汇的内涵与测量

接受性词汇指儿童能够理解其最基本词义的词汇, 它和表达性词汇是考察词汇量的两个不同角度(Laufer, 1998), 也被称为儿童语言大厦的基石(Wilkins, 1972)。儿童接受性词汇主要采取“图片−词汇”的测量方式, 其中皮博迪图片词汇测试工具(Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, PPVT)在全球使用范围最广(Dunn & Dunn, 2007)。PPVT面向2.5岁到90岁的人群。该工具基于英语语言体系研发, 信效度是基于美国的盎格鲁萨克逊文化人群进行的检验。PPVT通常经过直接翻译和简单修订后运用于其他语言或文化中, 虽有研究者指出同样的词汇在不同语言体系里难度不同(桑标, 缪小春, 1990), 不同文化下词语使用偏好不同(Finneran et al., 2020), 但其信效度往往也达到了可接受水平(Aram et al., 2013; Suggate et al., 2011)。

1.3 HLE与儿童接受性词汇的关系

根据Bronfenbrenner (1979)的生态系统理论, 儿童的成长受家庭、学校、社会等多个系统的共同作用, 其中距离最近的系统对儿童的作用最大。对幼儿(0~6岁)来说, 家庭无疑是主要的成长环境, 也是影响其语言能力发展最重要的系统。诸多研究发现, HLE与儿童接受性词汇不仅显著正相关(王娟, 沈秋苹, 2017), 前者亦是后者有效的预测因子(Lohndorf et al., 2018)。HLE不仅能解释遗传因素和SES作用之外的儿童读写能力的差异, 也是SES对儿童读写能力的中介路径(Korat et al., 2013; Lohndorf et al., 2018)。

家庭读写资源是支持读写活动开展的前提。研究发现, 家庭藏书量与儿童接受性词汇发展之间有较高的正相关, 儿童能获得的读物数量可以较大程度地解释其接受性词汇发展的个体差异(Burris et al., 2019)。一项元分析也发现, “家庭图书捐赠项目(Book Giveaway Programs)”能够显著激发儿童的阅读兴趣和行为, 并促进多项读写能力的发展(de Bondt et al., 2020)。同理, 各类游戏材料也能发挥积极的作用(Tomopouloset al., 2006)。很显然, 家庭读写资源对儿童接受性词汇发展的作用是基础的、关键的, 恰如Weinberger (1996)所说:在一个每天都会发生读写活动的环境中成长的儿童, 其语言发展有明显的优势。

动机氛围的作用路径有两条:一是父母自身的读写习惯, 虽然对儿童的直接作用小, 但父母对读写的热情会对儿童产生长期影响(李燕芳, 董奇, 2004), 有研究证实其与儿童接受性词汇发展存在显著正相关(Sénéchal & Lefevre, 2014)。二是父母读写信念, 包括对儿童读写活动重要性以及自己角色的认识、对儿童认知能力的信念以及未来学业成就的期望等, 这会直接影响父母参与读写活动的频次及互动行为, 从而对儿童接受性词汇发展产生影响(Gonzalez et al., 2017; Manolitsis et al., 2009)。

相较于前两方面, 家庭读写活动是影响儿童发展的最近端因素。从非正式读写活动来看, 亲子阅读历来是研究者们关注的核心指标。这是因为, 图画书中包含了更丰富、多元、日常生活中难以接触到的词汇(Zucker et al., 2013; Montag et al., 2015), 并且亲子在围绕图文结合的文本进行对话时, 更容易建立起“意义”和“词汇”之间的连接(Gettinger & Stoiber, 2014), 再加之图画书内容贴近儿童生活经验, 亲子互动的时长和话轮数也会更多(Gilkerson et al., 2017), 这些都是儿童接受性词汇学习的绝佳机会。围绕亲子阅读的诸多指标也被证实与儿童接受性词汇发展有显著正相关关系, 包括亲子阅读频率(Wasik et al., 2016)、儿童开始阅读的年龄(Mol et al., 2008)、儿童阅读兴趣(Shahaeian et al., 2018)、儿童请求阅读频率(Bonnett, 2007)、儿童自主阅读频率(Fielding- barnsley & Hay, 2012)。此外, 研究者们还发现在唱儿歌等室内游戏活动(Klein & Becker, 2017)以及去博物馆等外出文化活动(Kluczniok & Mudiappa, 2019)中, 儿童也能获得丰富的词汇学习机会。然而, 正式读写活动, 即教授儿童发音、识字、写字等活动则不同, 多项研究表明其促进的是儿童语音敏感性、识字量、书写技能等能力(Aram & Levin, 2004; Manolitsis et al., 2009)。

总体来看, 虽然已有研究对HLE与儿童接受性词汇间的关系进行了充分探究, 也对HLE几个方面的交互影响有初步讨论, 但HLE指标与儿童接受性词汇发展关系的强弱差异不明晰, 这限制了对HLE几个方面关系模型认识的深度, 故有必要拓展已有研究。综上, 本研究提出探索性假设1:除正式读写活动外, HLE整体及其他指标均与儿童接受性词汇发展有显著正相关关系, 各指标效应值差异有待考察。

1.4 HLE与儿童接受性词汇发展关系的调节变量

年代。HLE是一个与人类发展生态学密切相关的概念(Bronfenbrenner, 1979), 其形态与年代发展所带来的社会经济发展水平的变化紧密关联。研究表明, 从上世纪八九十年代至今, 电子媒介的涌入、读物种类的丰富、家庭其他学习活动及外出活动的显著增加对HLE及儿童早期读写经历带来了巨大冲击(Bassok et al., 2016; Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2019; Hiebert, 2015)。其中电子媒介的影响(平板电脑、智能手机等)尤其值得关注。据统计, 美国拥有电子设备的家庭从2011年的52%增长到2017年的98%, 儿童每天的屏幕时间长达2.16小时。受其影响, 家庭其他游戏时间降低, 传统亲子阅读只有39分钟(Rideout, 2017)。基于中国大湾区的研究发现了同样的趋势(李敏谊等, 2021)。电子媒介促使儿童的阅读从纸媒走向屏媒(张义宾, 周兢, 2016); 从静态图像文字走向文字、声音及影像符号的动态多感官融合, 根据媒介学习理论, 这会改变儿童在阅读中的意义建构及词汇学习过程(Mayer, 2003); 部分交互性设计也影响着父母的角色和亲子互动过程(Sosa, 2015)。可以说, 从21世纪开始, 电子媒介逐渐但显著地改变着HLE的形态以及儿童的生活、学习和思维方式, 也极有可能对儿童词汇的获得产生重要影响。因此, 提出假设2:年代可能会调节HLE与儿童接受性词汇发展的关系。同时, 亲子阅读作为传统HLE的典型代表, 也是电子媒介读写时代来临首当其冲被影响的指标, 故提出假设3:年代亦会影响亲子阅读频率与儿童接受性词汇发展的关系。

文化背景。所谓文化, 如霍夫斯泰德所说, 本质上是某种环境下人们共同拥有的心理程序, 能够把一群人和另外一群人区分开来(Hofstede et al., 2010)。在不同的文化中, 人们对儿童是什么样的、儿童应当发展哪些能力, 以及如何培养这些能力有不同理解, 这些信念影响着父母对HLE的创设以及对自身角色的认知(Keller et al., 2006; Super & Harkness, 2002)。例如, 东方文化往往关注儿童勤奋、专心、坚持的品质, 认为要尽早开始正式的学习活动, 这样才能不输在起跑线上, 即“勤有功, 戏无益”;然而西方文化则更强调儿童批判性思维、自我表达与交流、探索世界等能力, 认为儿童应当从游戏中学习, 学业训练尤其不符合学前儿童的年龄特征(Li, 2012; Parmar et al., 2004)。由此也不难理解, 相较于欧裔美国人, 华裔父母将更多时间用在数学运算等正式的学习活动上(Huntsinger et al., 1997)。总体来说, 东西方不同文化下父母的教育信念显著地影响着家庭读写材料的提供、活动的类型、时间的分配以及互动的方式(Parmar et al., 2004; Aminipour et al., 2020), 也必然会影响儿童接受性词汇的获得。此外, 从接受性词汇习得的角度来说, 文化会影响词汇的使用偏好(Xu & Liu, 2020)。PPVT是基于西方文化所研发的, 可能对东方文化下惯常使用的词汇不够敏感。综上, 提出假设4:文化背景可能会调节HLE与儿童接受性词汇发展的关系。

儿童年龄。儿童年龄的调节效应体现在两方面:(1)根据蒙台梭利的敏感期理论, 儿童语言发展并非匀速, 其在幼儿期对周围语言环境最为敏感, 发展速度最快, 小学阶段及以后则趋于平缓(蒙台梭利, 1936/2005; Standing, 1957)。换言之, 幼儿期的语言环境与接受性词汇发展的相关程度可能大于小学阶段。(2)在生态系统理论中, 时间系统(chronosystem)强调应当将时间和环境相结合来考察儿童发展的动态过程。具体来说, 一方面, 随时间推移儿童成长的微观系统会不断变化, 如儿童会逐渐从与他人共读过渡到独立阅读, 亲子阅读的频次和时间都会降低; 又如HOME量表专门研发了针对儿童不同年龄段的量表, 而非像问卷一样未做区分(Bradley&Caldwell, 1988)。另一方面, 儿童也会面临“生态转变” (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998; 刘杰, 孟会敏, 2009)。幼小衔接阶段是儿童成长中的转折期, 小学阶段儿童的语言发展目标、学习内容和方式均与学龄前有明显不同, 更具系统性。HLE的作用不但会被进一步分散, 学校还可能逐步替代家庭发挥更大的作用。因此, 综合以上两种理论, 本研究以儿童从幼儿园到小学的年龄为界限, 将儿童划分为6岁前(2.5岁~ 6岁)和6岁后两组, 并提出假设5:儿童年龄可能会调节HLE与接受性词汇发展的关系, 6岁前效应值高于6岁以后。同理, 针对亲子阅读提出假设6:儿童年龄可能会调节亲子阅读频率与接受性词汇发展的关系, 6岁前效应值高于6岁以后。

测量方法。HLE有问卷法和现场观察法两种。问卷法属于父母自我汇报, 虽有一定的信效度(Dickinson & deTemple, 1998), 但可能存在回忆困难、题目理解偏差、社会期望偏误, 以及难以表述复杂问题等缺点; 现场观察法目前只有HOME量表, 能有效避免问卷法的缺点, 收集的资料更加客观准确(刘丽, 石岩, 2012; Switzer et al., 1999), 并且在测量内容上也超越了问卷法, 涵盖了对互动质量的评估。因此, 提出假设7:测量方法可能会影响HLE的效应值, 现场观察法效应值高于问卷法。在HLE指标中, 研究者们围绕亲子阅读频率的测量有诸多探索, 主要有问卷法和书目清单法(Children Title Checklist, CTC)。CTC以信号检测论为心理测量学基础, 请被试从所提供的真假书名清单中再识别出真正的书名, 这是为了降低问卷法偏误而专门提出的(Stanovich & West, 1989; Cunningham & Stanovich, 1991, 1993)。虽然有研究指出其与问卷法测量内容较为一致(赵瑾东等, 2008; Hamilton et al., 2016), 但有不少研究发现, CTC与儿童词汇发展的相关程度更高、稳定性更强(Sénéchal et al., 1996)。由此, 提出假设8:测量方法可能会影响亲子阅读频率的效应值, CTC效应值高于问卷法。

2 研究方法

2.1 文献检索及筛选

本研究通过篇名、主题词、关键词、摘要的方式检索中英文文献, 所检索文献的发表时间跨度为1990年1月至2021年5月(Bus等人最具影响力的元分析发表于1995年, 本论文续接此研究)。中文文献检索使用中国知网、万方、TWS台湾学术期刊在线数据库, 使用家庭读写环境、家庭学习环境、家庭读写活动、家庭学习活动、家庭阅读环境和亲子阅读六个环境词汇, 分别搭配接受性语言、接受性词汇、皮博迪图片词汇测试和PPVT四个儿童语言发展词进行检索。英文检索使用Web of Science核心合集、EBSCO、ProQuest博硕论文库、Scopus、SAGE Journals、Wiley、Emerald、Springer Link, 使用home literacy environment、home language environment、home learning environment、home literacy activity、emergent literacy、shared reading、joint reading和book exposure八个环境词, 分别搭配vocabulary、receptive language和PPVT三个儿童语言发展词进行检索。

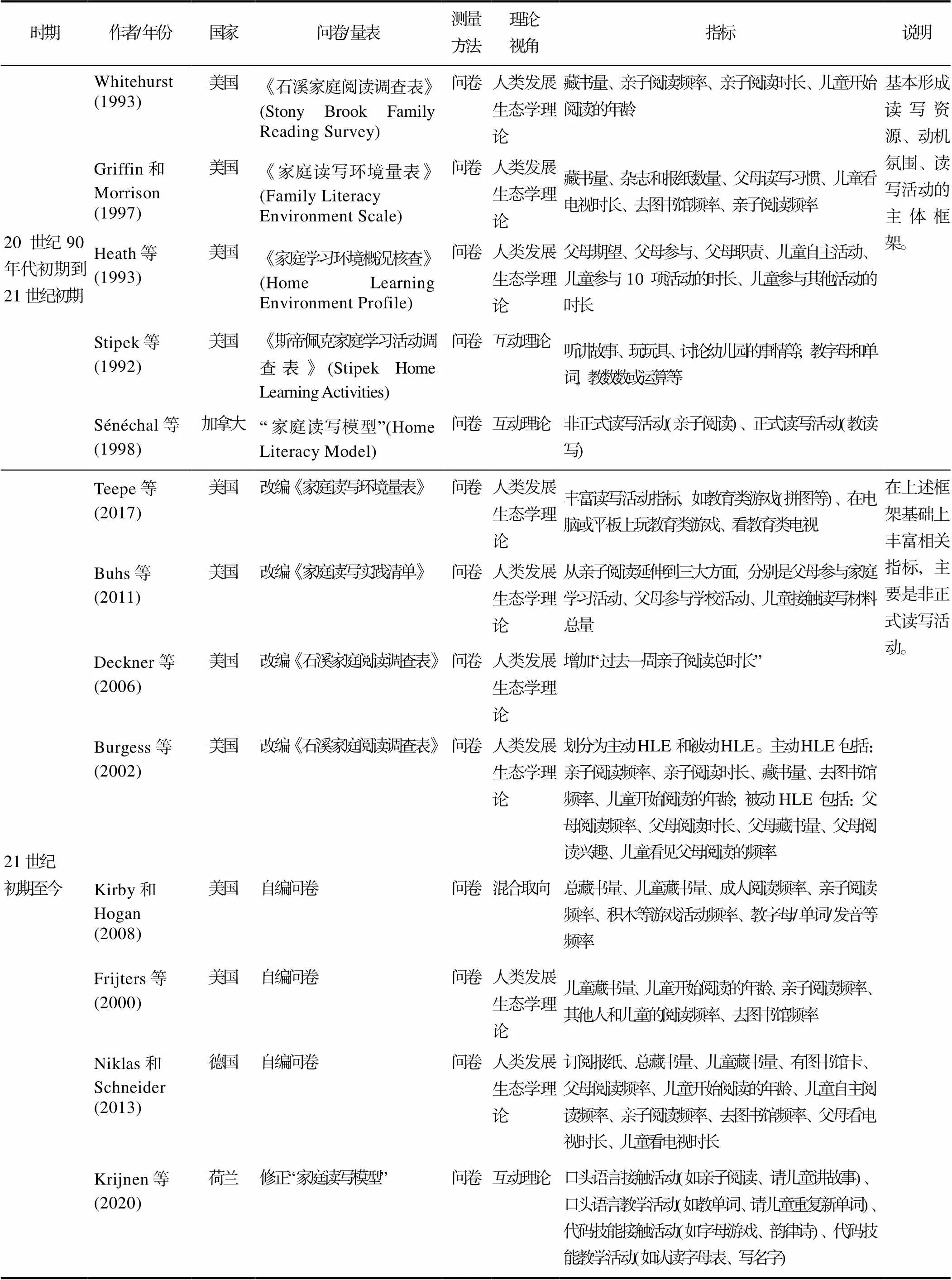

使用NoteExpress导入文献并按照如下标准筛选:(1)研究汇报了HLE整体或至少某一指标与儿童接受性词汇发展的相关关系; (2)研究详细描述了HLE的结构, 明晰了每一条指标所测查的具体内容; (3)由于本研究关注HLE与儿童接受性词汇的相关关系, 因此二者的测查需在同一时期完成; (4)对于实验或准实验研究, HLE与儿童接受性词汇的测查须在实验开始之前, 以保证二者相关系数未受到实验影响; (5)儿童接受性词汇测量工具为PPVT; (6)研究发表于1990年1月至2021年5月, 且发表于经过同行审议的期刊论文, 或为硕博士学位论文、书籍篇章。排除:(1)语言发展缓慢或残障儿童; (2)第二语言学习过程; (3)非中英文文献。文献筛选流程如图1所示, 初步纳入了88项独立研究。

2.2 效应值提取、文献质量评估及变量编码

由于各研究中HLE内涵及指标不一致, 先根据研究内容确立HLE效应值提取框架(见表2)。提取效应值时遵循如下原则:(1)有关HLE和读写活动这两个综合性指标。HLE必须涵盖三大方面, 若虽定义为HLE问卷, 但指标只涉及读写活动,则不提取; 读写活动需同时涵盖非正式读写活动和正式读写活动方可提取。(2)部分研究是基于早期数据库进行的分析, 即数据收集年份和文章发表年份存在较大出入, 对此类情况, 本研究同时提取两个年份, 计算时以数据收集年份为准。

图1 文献检索及效应值提取流程图

表2 HLE效应值提取框架

最终, 有4项研究由于指标混杂, 不满足效应值提取条件而未能编码并纳入计算。由于父母阅读时长、父母阅读兴趣、亲子阅读时长、儿童自主阅读频率、其他学习活动这几项指标效应值数量均在1~3之间, 为了保障分析结果的可靠性, 有9个效应值只编码但并未纳入分析。本研究最终编码并纳入计算的有84项研究, 涉及212个效应值, 样本总量为65550人。

文献质量评估参照实验和干预类研究评价条目与标准以及张亚利等人(2019)的做法, 包括了对被试的选取、数据有效率、测量工具的内部一致性信度、刊物级别四个方面的评估。每条文献总分介于0~10之间, 得分越高表明文献质量越好。该评价过程由两位评分者独立完成, 一致性Kappa值为0.96。

对最终纳入元分析的文献进行如下编码(见表3):作者、文献类型(期刊/学位论文/书籍)、发表年份及数据收集年份、样本量、被试年龄、国家、文化(西方文化/东方文化/其他)、HLE及各指标与PPVT相关系数、文献质量、HLE测量工具(问卷/HOME)、亲子阅读频率测量工具(问卷/CTC)。其中, 对文化背景的判断则参考了霍夫斯泰德等人的研究。该研究根据文化的六维度(权力距离、个人主义与集体主义、社会文化维度的阳刚气质与阴柔气质、对社会中不确定性容忍度、长期导向和短期导向、社会维度的放纵与克制)对不同国家及地区的文化进行了深入的刻画(Hofstede et al., 2010; Hofstede, 2011)。本研究基于上述成果把来自不同文化圈的研究样本划分为上述三个类别。编码工作由第一作者独立完成, 有异议方面与通讯作者深入协商直到达成一致。为保证编码质量, 研究团队培训研究助理并随机选取9篇(11%)进行编码, 其与第一作者编码结果的一致性为94.3%。

2.3 数据分析

运用CMA-3.0 (comprehensive meta-analysis 3.0)软件进行元分析, 选择相关系数()作为效果量, 具体是将值转换为Fisher’s值后进行元分析, 最后再将Fisher’s的加权平均数转换为相关系数, 得到总体效应值并估算95%置信区间。对于部分文献没有直接报告HLE整体及各指标与儿童接受性词汇发展的相关系数, 而是报告了值,值,c2值或回归系数, 则采用已有研究方法转换为值(Card, 2012; Peterson & Brown, 2005), 即= [2/ (2+)]1/2,=1+2− 2;= [/ (+)]1/2,=1+2− 2;= [c2/ (c2+)]1/2;= 0.98+ 0.05 (≥ 0),= 0.98(< 0), 再将r值转换为Fisher’s值后进行元分析(Borenstein et al., 2009)。

表3 HLE与儿童接受性词汇关系的元分析编码表

续表

续表

续表

注:a:本列只标注第一作者, 作者后标注“硕”“博”的为学位论文, 标注“书”的为书籍篇章, 未做标注的为期刊论文; b:1 = 西方文化, 2 = 东方文化, 3 = 其他; c:1 = 问卷, 2 = HOME; d:1 = 问卷, 2 = CTC。

*代表该类效应值较少而未进行后续分析。

3 研究结果

3.1 发表偏倚检验

发表偏倚(publication bias) 是指已发表的研究文献不能系统全面地代表该领域已经完成的研究总体(Rothstein et al., 2006), 这会影响元分析结果的可靠性。本研究在文献检索阶段尽可能提高查全率, 同时采用漏斗图(funnel plot), 失安全系数(Classic Fail-safe)、Egger’s回归系数、修剪填补法(Trim and fill)进行检验(见表4)。首先采用漏斗图进行评估。由于漏斗图对于只包含10个及以内的Meta分析效率较低(杨书等, 2007), 因此仅用此方法分析研究数较多的5个HLE的指标效应值, 结果显示不存在严重的发表偏倚问题。其次, 失安全系数结果显示, 除“儿童开始阅读的年龄”小于临界值5+ 10 (Rothstein et al., 2006; Borensteinet al., 2009)之外, 其他指标均不存在发表偏差; 再者, Egger’s上的值以及修剪填补法显示了与失安全系数同样的结果。综上, 本研究中除“儿童开始阅读年龄”可能存在发表偏倚之外, HLE整体及其他指标与儿童接受性词汇发展之间的元分析结果较为可靠。

3.2 异质性检验

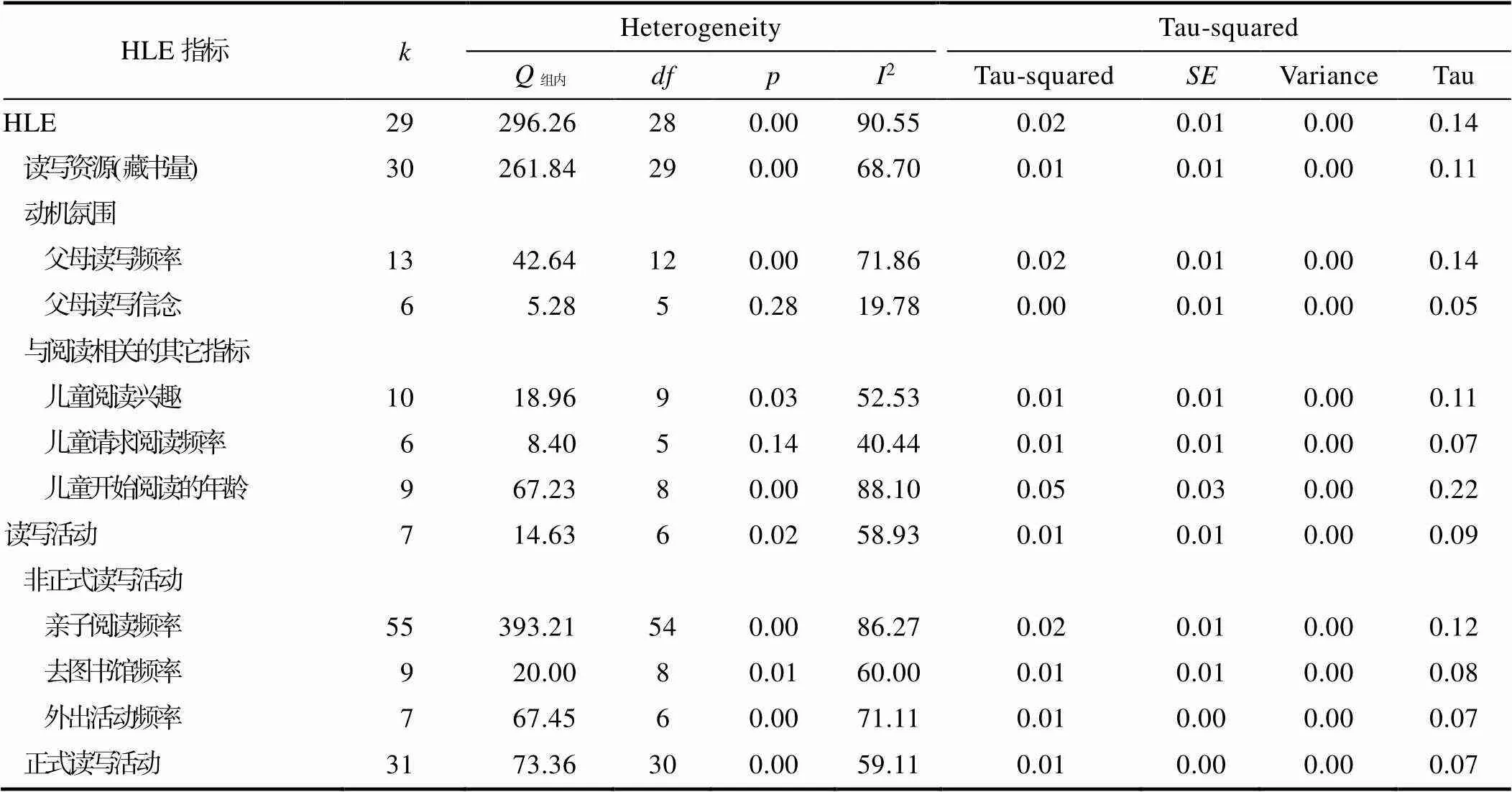

异质性检验通过检验和2检验进行。结果显示(见表5):HLE的值达到显著水平,= 296.26,< 0.05, 说明各效应量之间异质。异质性程度的高低由I区分, 25%、50%、75%是区分低、中、高异质性的分界(Higgins et al., 2003)。HLE的2是90.55, 代表有90.55%的观察变异是由效应值的真实差异造成的。各指标中, 亲子阅读频率异质性较高(= 393.48,< 0.05;2= 86.27), 后续需和HLE一起进行调节效应检验; 儿童开始阅读的年龄同样有较高的异质性, 但由于存在发表偏倚, 后续不进行调节效应检验。总体来看, 由于HLE和多个指标均呈现中高程度的异质性, 本研究采用随机效应模型。

表4 出版偏误检验结果

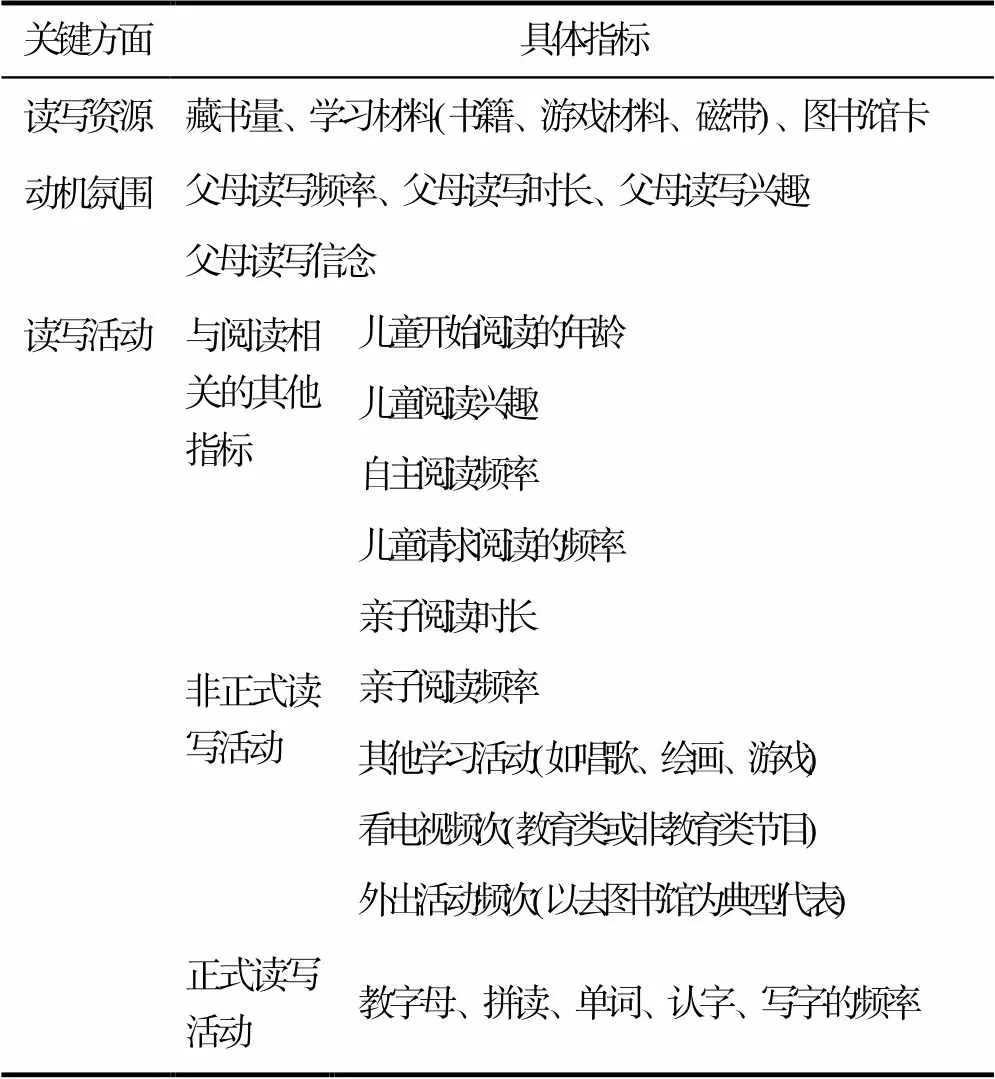

3.3 主效应检验

主效应分析结果显示(见表6):HLE与儿童接受性词汇发展的相关系数为0.31, 95%置信区间为0.26~0.36。根据Cohen (1988) 建议的相关系数大小的解释标准(= 0.1为低相关,= 0.3为中等相关,= 0.5为强相关), 可以认为两者存在中等程度的正相关。敏感性分析发现, 排除任意一个样本后, HLE的效应值在0.29~0.32间浮动, 说明元分析估计结果具有较高的稳定性。HLE各指标中, 效应值由高到低为:亲子阅读频率(= 0.26,< 0.05)、读写资源(藏书量) (= 0.26,< 0.05)、父母读写信念(= 0.25,< 0.05)、儿童请求阅读的频率(= 0.25,< 0.05)、父母读写频率(= 0.20,< 0.05)、去图书馆频率(= 0.19,< 0.05)、儿童阅读兴趣(= 0.17,< 0.05)和读写活动(= 0.17,< 0.05)。外出活动频率(= 0.09,< 0.05)和正式读写活动(= 0.07,< 0.05)不相关。敏感性分析亦说明结果均具有较高的稳定性。儿童开始阅读的年龄由于存在发表偏倚, 表格中为修剪填补法后结果, 显示与儿童接受性词汇发展不相关(= 0.06)。

表5 异质性检验结果

注:代表效应值个数。

表6 主效应检验结果

注:代表效应值个数,代表样本量, 95% CI代表各效应值的95%置信区间(包括上限和下限)。

3.4 调节效应检验

采用元回归分析对HLE和亲子阅读频率的效应值分别进行调节效应检验。相较于亚组分析, 元回归分析能够在控制其他调节变量的情况下分析某一调节变量的单独作用。结果显示:对于HLE与儿童接受性词汇发展关系来说, 只有年代的调节效应显著, 其中1990~1999年的效应值显著高于2000~2009 (< 0.05)和2010~2021 (< 0.05)年代, 后两个亚组效应量的95% CI有重叠区间, 这意味着差异不具有统计学意义(表7)。为了进一步避免可能出现的假阳性结果, 对值进行Bonferroni校正(张天嵩, 张苏贤, 2017), 结果显示2000~ 2009年代与2010~2021年代的差异依然不显著(表8)。模型总体解释率为18%。

对于亲子阅读频率与儿童接受性词汇发展关系来说, 只有测量工具调节效应显著(< 0.05) (见表7)。对年代的亚组进行两两比较, 并对值进行Bonferroni校正后发现, 亚组间均不存在显著差异(见表8)。该模型总体解释率较低, 结果有待于进一步考察。

4 讨论

4.1 HLE与儿童接受性词汇发展的关系

HLE与儿童接受性词汇发展关系为中等相关, 这与大量实证研究结果一致(Lohndorf et al., 2018; Bojczyk et al., 2019)。在各指标中, 围绕亲子阅读的各项指标效应值最大, 包括读写资源(藏书量) (= 0.26)、亲子阅读频率(= 0.26), 以及儿童请求阅读的频率(= 0.25); 其次是动机氛围下的父母读写信念(= 0.25)和父母读写频率(= 0.20)两项; 再者为读写活动中的去图书馆频率(= 0.19); 最后是外出活动频率(= 0.09)、正式读写活动频率(= 0.07)和儿童开始阅读的年龄(= 0.06)三项指标。各指标效应值的差异启发要进一步思考HLE指标间的关系。在前文梳理中发现, 父母读写信念会影响读写资源的投入及各类读写活动的参与, 对HLE质量有整体性作用(Gonzalez et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2018), 但父母的读写信念需转化为适宜的行动才能促进儿童发展。从最直接促进儿童接受性词汇发展的角度来看, 本研究发现当属各种类型的阅读活动, 包括亲子阅读、去图书馆等。藏书量曾被认为是从测量层面能代表HLE质量的稳定且有力的指标(Mol & Bus, 2011), 本研究支持了这一结论, 但认为其效应值高的根本原因可能还是与家庭对阅读活动的享受程度及阅读行为高度相关(Evans et al., 2010)。外出活动效应值低可能还需考量活动内容及互动质量, 而正式读写活动效应值与假设一致, 发展的是识字量等其他语言能力。需特别注意的是, 儿童开始阅读的年龄存在发表偏倚, 其主要原因在于研究者在正负计分方式上有差异。虽然在本研究中效应值较低, 但以往研究认为儿童开始阅读的年龄代表了儿童的累积阅读量, 是预测儿童口头语言发展的显著指标(DeBaryshe & Binder, 1994; Mol et al., 2008), 因此对这一结果的解释需慎重。

表7 调节变量的元回归分析

注:b为非标准化回归系数; *< 0.05, **< 0.01.

表8 年代的三个亚组效应量两两比较结果

基于上述分析, 本研究超越已有实证研究进一步认识到, 在HLE的各指标中, 围绕亲子阅读活动开展的资源和机会是与儿童接受性词汇发展最紧密的要素。这一结果也启发相关干预研究一方面提升父母的读写信念, 另外还可以进一步聚焦亲子阅读倡导、图书捐赠、社区图书馆建设等具体做法。

4.2 调节变量的影响

4.2.1 年代的调节作用

元分析结果发现, 年代是HLE与儿童接受性词汇发展关系的调节变量, 从1990年到2021年, HLE效应值显著降低, 假设2得到支持; 但年代对亲子阅读频率与儿童接受性词汇关系的调节作用不显著, 即近30年来亲子阅读的作用较稳定, 假设3未得到支持。出现这一结果的可能原因有两方面:

一是随着时代和社会经济的发展, HLE与儿童接受性词汇关系的确逐步降低。从家庭内部来说, 电子媒介可能带来了不利影响。电子媒介的普及让更多的儿童在更低年龄段开始使用电子产品(Rideout, 2017), 这大大减少了原来用于游戏和亲子阅读的时间(Buset al., 2020; Pagani et al., 2010; 杨晓辉等, 2016; 李敏谊等, 2021)。虽然部分研究指出部分内容和形式适宜的节目或软件蕴含着丰富的词汇学习的策略, 能促进接受性词汇的发展(Danielson et al., 2019;Hu et al., 2020; Marulis & Neuman, 2013)。但相较于传统玩具或书籍, 儿童在看电子媒介产品时, 成人的语言及回应、亲子互动话轮数、儿童自己的语言, 以及围绕具体内容的词汇讨论都更少(Sosa, 2015)。此外, “电子保姆” (吴瑶, 2016)、“视频致呆” (Anderson & Hanson, 2010), 以及产品质量问题(张义宾, 周兢, 2016)普遍存在, 都可能对儿童接受性词汇发展带来危机。因此, 电子媒介所带来的机遇和风险并存, 未来还需更多研究的深入探讨。从家庭之外的环境来说, 托幼机构的影响日益凸显。具体表现在:一方面入园率不断提升。始于20世纪60年代中期的学前教育规模的扩张是一个全球性现象, 全球学前教育毛入园率从1965年的不足10% (Inkeles & Sirowy, 1983), 到2019年已超过61.5% (World Bank, 2021)。另一方面儿童入园时长持续增加。美国国会发布的《教育概况2020》(The Condition of Education 2020)显示, 从2000年到2018年, 虽然3~5岁儿童的入园率没有明显变化, 但相较于半日制的托幼机构而言, 进入全日制学前班(kindergarten)的儿童比例从60%上升到了81%, 进入全日制幼儿园(preschool)的比例从47%上升到了54% (Hussar et al., 2020)。结合儿童入园时长与语言发展的正相关关系(Klein & Becker, 2017), 有理由推断HLE对儿童接受性词汇的作用受到了托幼机构的分散。二是电子媒介时代HLE的真实效应值尚不明确。换言之, 随时代发展, HLE工具的效度逐步降低, 基于传统印刷品时代研发的HLE工具已无法充分捕捉并反映电子媒介时代下HLE的真实效应值。如前所述, HLE框架虽然全面, 但近年来指标的变化仅限于在问卷中增加几项指标, 这是否能真实反映出HLE的巨大变化值得深入思考。因此, 后续应思考如何结合童年与家庭生活的变迁来拓展HLE的工具研究。

值得注意的是, 虽然年代变迁, 亲子阅读频率的效应值一直中等且稳定。这不仅说明亲子阅读是影响儿童接受性词汇发展的强有力的指标, 也验证了互动理论所主张的人与人之间的互动才是儿童语言发展的核心和关键这一理念。这同时也与一项关于电子阅读的元分析结果相呼应, 该研究发现, 成人是否伴读对儿童的理解力有显著的调节作用(吕雪等, 2019)。因此, 无论HLE的形态发生何种变化, 亲子互动的价值和意义应当得到充分的认识。

4.2.2 文化背景的调节作用

元分析结果发现, 文化背景对HLE与儿童接受性词汇关系的调节作用不显著, 假设4未得到支持。对此有两种可能的解释:一是东西方文化下的效应值无差异, 即虽然东西方文化在教育目标及方法的信念以及家庭读写活动类型等方面有差异, 但对儿童接受性词汇发展的总体效果是一致的。这种可能性较低, 因为从本研究中就能看出不同类型的读写活动的效应值是有区别的。二是东西方文化下的效应值有差异, 但一方面, 本研究的样本中基于东方文化的研究太少(仅占13.8%), 在统计效力上未达显著水平。另外更值得关注的是, 当前国际范围内HLE的评估工具多是基于西方文化研发的, 未必能反映出东方文化下HLE的全部要素, 同时PPVT也产生于西方文化和英语语言环境, 鉴于不同文化下的常用词汇使用偏好以及不同的语言体系中同一词汇的难易程度的差异, 经翻译后的PPVT亦未必能有效测量出儿童真实的词汇水平(Finneran et al., 2020; Xu & Liu, 2020), 以上因素均使得东方文化下HLE的效应值依然处于黑箱之中。因此, 虽然研究者们很早就注意到不同文化下HLE的差异(Buhs et al., 2011; 李燕芳, 董奇, 2004), 但从跨文化视角开展的研究依然欠缺, 不同文化下HLE和儿童接受性词汇发展的测量工具更是少有, 未来需要更多跨文化研究对此问题做深入剖析。

4.2.3 儿童年龄的调节作用

元分析结果表明:儿童年龄对HLE及亲子阅读频率与儿童接受性词汇发展关系的调节作用均不显著, 假设5和6未得到支持。可能的原因在于:第一, 需考虑互动质量。如果互动过程并不那么愉快, 父母对儿童的需求并不那么敏感, 反而会给儿童的读写能力和兴趣带来负面影响(van Ijzendoorn et al., 1995)。第二, HLE及亲子阅读频率对儿童接受性词汇的发展存在滚雪球效应(Raikes et al., 2006)。对HLE得分高或亲子阅读频率高的儿童来说, 小学阶段不仅受当前HLE的积极作用, 还依然受到小学前所经历的高质量HLE的持续影响, 即这些儿童在语言发展敏感期时储备了更多的接受性词汇, 进入小学后从个体语言发展曲线来看虽然速度变缓, 但相较于其他同龄人, 从课堂内外获取新词汇的能力更强, 小学更加广阔的环境反而丰富了词汇获取的契机, 使其与同龄人之间的优势越来越明显, 最终从数据上出现HLE与儿童接受性词汇相关程度依然高的情况。这不仅体现了学前期儿童语言发展的奠基性作用, 更充分说明了童年早期为儿童创设高质量HLE及开展亲子阅读的重要意义。

4.2.4 测量方法的调节作用

元分析结果表明, HLE的两种测量方法所得效应值无差异。这可能是因为, 一方面问卷和HOME测量内容有较高的重合度, 另一方面, 虽然问卷虽会带来社会期望偏误, 但现场观察也会有观察者效应、评分者一致性, 或某次观察并不一定代表日常情况等问题。总体上假设7未得到支持。元分析结果还发现, 对亲子阅读频率来说, CTC所得效应值比问卷法更高、更稳定, 这与已有研究结果一致(Sénéchal, 2006;赵瑾东等, 2008;Mol & Bus, 2011), 假设8得到支持。但CTC也会存在地板效应或天花板效应(McQuillan, 2006; Sénéchal, 2006), 使用时还需综合考量。此处需引起重点关注的是, 本研究发现不同研究者对CTC所测内容理解不一致。该方法最初是Sénéchal等人(1996) 在Stavioch团队基础上为了降低社会期望偏误正式提出的, 认为这是一种通过父母对儿童读物的熟悉程度来间接测量亲子阅读频率的方法, 其背后的假设是与儿童阅读频率越高的父母对儿童读物的熟悉和了解程度越高。虽然Sénéchal团队在部分研究中也认为其是非正式读写活动的间接测量方法, 但在当时非正式读写活动的主要指标就是亲子阅读。在后续研究中研究者的理解开始出现差异, 主要分为以下三类。第一, 认为其与亲子阅读频率所测量内容相同(Farveret al., 2006; 赵瑾东等, 2008; Hamilton et al., 2016)。第二, 认为内涵大于亲子阅读频率, 如有研究者沿用了非正式读写活动这一说法, 但这时候非正式读写活动内涵已经扩展到了亲子阅读频率、访问图书馆频率、购买书籍等(陈晓等, 2010; Skwarchuk et al., 2014)。Mol和Bus (2011)指出, 如果将问卷所测量的内容扩大, 包括去图书馆或书店频次、儿童开始阅读的年龄等, 那么问卷和CTC所得结果接近。第三, 认为CTC跟亲子阅读频率所测内容不同但彼此高度相关。Zhang等人(2018)经过探索性因子分析后指出, 亲子阅读频率和CTC是不同的因子, CTC测量的是父母对儿童读物的熟悉程度, 这不一定是通过亲子阅读才可获知, 亦有可能通过网上购物、图书馆等多种渠道获知, 但在回归分析中发现两者对儿童接受性词汇的回归系数却几乎等同, 因此认为这两者是内涵不同但高度相关的方面。本研究在数据提取与分析时, 按照CTC方法最初提出者的预设将其等同于亲子阅读频率的间接测量方法, 然而显著的差异提醒研究者, 书目清单所测量的内涵可能发生了变迁, 这也有待后续研究继续深入跟进。

4.3 不足与展望

本研究存在以下不足:(1)文献检索和纳入方面。首先, 元分析方法对文献要求严格, 尽管尽可能地扩大搜索范围, 但受到语言和检索工具的限制, 难免有所疏忽。其次, HLE指标较多, 本研究仅从HLE整体和亲子阅读着手进行了检索, 虽能涵盖大部分文献, 但必然会有遗漏; 再者, 有部分研究并未汇报HLE与儿童接受性词汇的相关系数(Fielding-barnsley & Hay, 2012; Inoue et al., 2018), 这在文献及数据纳入上也造成了一定的损失。(2)由于HLE指标较为复杂, 为了保证最大程度分析HLE对接受性词汇发展的影响, 降低接受性词汇评估工具带来的变动, 本研究将接受性词汇的评估工具限定在了使用的最为广泛的PPVT上。(3)不少研究注意到亲子互动等过程性质量的重要性, 但由于关注点及测量方法差别较大(Hindman et al., 2008; Bojczyk et al., 2016), 本研究未纳入分析。未来研究仍待解决的问题:(1)借助元分析方法更加全面地探究HLE与儿童不同语言能力发展之间的关系。(2)以发展的眼光思考HLE的评估, 从测量内容和方法的角度重构电子媒介时代HLE的测量, 突破互动质量的评价的难点, 并重新审视CTC的评估内容。(3) 基于跨文化视角探究不同文化下HLE的内涵及测量问题(Taylor, 2000; Gonzalez et al., 2011; Niklas et al., 2016), 比较差异并分析文化所发挥的作用。

5 结论

本研究得出如下结论:(1)以家庭读写资源、动机氛围和读写活动为核心的HLE与儿童接受性词汇发展之间存在中等程度正相关。各指标中, 除儿童开始阅读的年龄由于发表偏倚还需进一步探究, 以及外出活动和正式读写活动与儿童接受性词汇不相关外, 其余指标均为小到中等程度效应值。(2)对HLE来说, 年代的调节作用显著, 效应值随时代发展显著降低, 未见文化背景、儿童年龄、测量方法的调节作用; 对HLE核心指标亲子阅读频率来说, 测量方法调节作用显著, CTC测量所得效应值显著高于问卷法, 但未见年代和儿童年龄的调节效应。

(带*为元分析纳入文献)

*陈晓, 周晖, 赵瑾东. (2010). 儿童家庭读写活动、早期读写水平与小学一年级语文课成绩的关系.(3), 258−266.

李敏谊, 张祎, 王诗棋, 秦思语. (2021). 幼小衔接阶段儿童的屏幕时间、纸读时间与早期读写能力的关系研究.(2), 102−108.

李燕芳, 董奇. (2004). 儿童早期读写能力发展的环境影响因素研究.(3), 531−535.

*林珮伃. (2012). 家庭语文环境与儿童接受性词汇的表现., 23−44.

刘杰, 孟会敏. (2009). 关于布郎芬布伦纳发展心理学生态系统理论.(2), 250−252.

刘丽, 石岩. (2012). 临床运动心理学研究:现状、问题与建议.(9), 1495−1506.

吕雪, 郭力平, 蒋路易. (2019). 电子阅读对年幼儿童故事理解的影响——基于24篇论文的元分析.(4), 76−84.

蒙台梭利, M. (2005).(马荣根,单中惠译). 北京:人民教育出版社.

桑标, 缪小春. (1990). 皮博迪图片词汇测验修订版(PPVT—R)上海市区试用常模的修订.(5), 22−27.

*王娟, 沈秋苹. (2017). 家庭读写环境对儿童词汇发展的影响——母亲语言支架的中介效应.,(4), 750−753.

吴瑶. (2016). 儿童数字阅读变革与反思., (2), 40−44.

*晏盈盈. (2015).(硕士学位论文). 陕西师范大学, 西安.

杨书, 李婷婷, 刘新. (2007). 应用漏斗图识别发表性偏倚的效率研究.(1), 33−34.

杨晓辉, 王振宏, 朱莉琪. (2016). 促进低龄儿童发展的电子媒体使用., (11), 24−37.

张天嵩, 张苏贤. (2017). 如何实现Meta分析中不同亚组合并效应量的比较.(12), 1465− 1470.

张亚利, 李森, 俞国良. (2019). 自尊与社交焦虑的关系: 基于中国学生群体的元分析.(6), 1005−1018.

张义宾, 周兢. (2016). 纸媒还是屏媒?——数字时代儿童阅读的选择.(12), 24−30.

*赵瑾东, 周晖, 陈晓. (2008). 幼儿书目清单的编制及其与口头词汇的关系.,(1), 14−18.

Aminipour, S., Asgari, A., Hejazi, E., & Roßbach, H. G. (2020). Home learning environments: A cross-cultural study between Germany and Iran.,(4), 411−425.

Anderson, D. R., & Hanson, K. G. (2010). From blooming, buzzing confusion to media literacy: The early development of television viewing.(2), 239−255.

*Aram, D., Korat, O., & Hassunah-Arafat, S. (2013). The contribution of early home literacy activities to first grade reading and writing achievements in Arabic.,(9), 1517−1536.

Aram, D., & Levin, I. (2004). The role of maternal mediation of writing to kindergartners in promoting literacy in school: A longitudinal perspective.,(4), 387−409.

*Aram, D., & Shapira, R. (2012). Parent-child shared book reading and children’s language, literacy, and empathy development.,(2), 55−65.

*Baroody, A. E., & Diamond, K. E. (2012). Links among home literacy environment, literacy interest, and emergent literacy skills in preschoolers at risk for reading difficulties.,(2), 78−87.

Bassok, D., Finch, J. E., Lee, R., Reardon, S. F., & Waldfogel, J. (2016). Socioeconomic gaps in early childhood experiences.,(3), 233285841665392.

*Bingham, G. E., Jeon, H., Kwon, K., & Lim, C. (2017). Parenting styles and home literacy opportunities: Associations with children’s oral language skills.(5), 1−18.

Bojczyk, K. E., Davis, A. E., & Rana, V. (2016). Mother−child interaction quality in shared book reading: Relation to child vocabulary and readiness to read.,, 404−414.

*Bojczyk, K. E., Haverback, H. R., & Pae, H. K. (2018). Investigating maternal self-efficacy and home learning environment of families enrolled in Head Start.,(2), 169−178.

*Bojczyk, K. E., Haverback, H. R., Pae, H. K., Hairston, M., & Haring, C. D. (2019). Parenting practices focusing on literacy: A study of cultural capital of kindergarten and first-grade students from low-income families.,(3), 500−512.

*Bonnett, R. (2007). Relation of home literacy, parental support, and child initiation of reading to emergent literacy in Head Start preschool children.,(9), 1689−1699.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (Eds). (2009).. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons.

*Bracken, S. S., & Fischel, J. E. (2008). Family reading behavior and early literacy skills in preschool children from low-income backgrounds.,(1), 45−67.

Bradley, R. H., & Caldwell, B. M. (1988). Using the HOME inventory to assess the family environment., 97−102.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979).. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (1998). The ecology of developmental processes. In W. Damon, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.),(pp. 993−1023). New York, NY: Wiley.

*Buhs, E. S., Welch, G., Burt, J., & Knoche, L. (2011). Family engagement in literacy activities: Revised factor structure for The Familia-an instrument examining family support for early literacy development.,(7), 989−1006.

*Bulotsky-Shearer, R. J., Wen, X., Faria, A.-M., Hahs-Vaughn, D. L., & Korfmacher, J. (2012). National profiles of classroom quality and family involvement: A multilevel examination of proximal influences on Head Start children’s school readiness.(4), 627−639.

Burgess, S. R., Hecht, S. A., & Lonigan, C. J. (2002). Relations of the home literacy environment (HLE) to the development of reading-related abilities: A one-year longitudinal study.,(4), 408−426.

*Burris, P. W., Phillips, B. M., & Lonigan, C. J. (2019). Examining the relations of the home literacy environments of families of low SES with children’s early literacy skills.,(2), 154−173.

Bus, A. G., Neuman, S. B., & Roskos, K. (2020). Screens, apps, and digital books for young children: The promise of multimedia.,(1), 233285842090149.

Bus, A. G., van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Pellegrini, A. D. (1995). Joint book reading makes for success in learning to read: A meta-analysis on intergenerational transmission of literacy.,(1), 1−21.

Camisón-Zornoza, C., Lapiedra-Alcamí, R., Segarra-Ciprés, M., & Boronat-Navarro, M. (2004). A meta-analysis of innovation and organizational size.(3), 331−361.

Card, N. A. (2012).. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

*Chamberlain, S. E. (2003).? (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of South California.

*Chansa-Kabali, T. (2017). Home literacy activities: Accounting for differences in early grade literacy outcomes in low-income families in Zambia., 1−9.

*Chazan-Cohen, R., Raikes, H., Brooks-Gunn, J., Ayoub, C., Pan, B. A., Kisker, E. E., … Fuligni, A. S. (2009). Low-income children's school readiness: Parent contributions over the first five years.(6), 958−977.

*Christian, K., Morrison, F. J., & Bryant, F. B. (1998). Predicting kindergarten academic skills: Interactions among child care, maternal education, and family literacy environments.,(3), 501−521.

Cohen, J. (1988).(2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

*Crystal, C. (2013).(Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

Cunningham, A. E., & Stanovich, K. E. (1991). Tracking the unique effects of print exposure in children: Associations with vocabulary, general knowledge, and spelling.,(2), 264−274.

Cunningham, A. E., & Stanovich, K. E. (1993). Children’s literacy environments and early word recognition subskills.,(2), 193−204.

*Daniels, J. K. (2004).(Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Maryland.

Danielson, K., Wong, K. M., & Neuman, S. B. (2019). Vocabulary in educational media for preschoolers: A content analysis of word selection and screen-based pedagogical supports.,(3), 345−362.

*Davidse, N. J., de Jong, M. T., Bus, A. G., Huijbregts, S. C. J., & Swaab, H. (2011). Cognitive and environmental predictors of early literacy skills.,(4), 395−412.

de Bondt, M., Willenberg, I. A., & Bus, A. G. (2020). Do book giveaway programs promote the home literacy environment and children’s literacy-related behavior and skills?,(3), 349−375.

DeBaryshe, B. D., & Binder, J. C. (1994). Development of an instrument for measuring parental beliefs about reading aloud to young children.,(3_suppl), 1303−1311.

*Deckner, D. F., Adamson, L. B., & Bakeman, R. (2006). Child and maternal contributions to shared reading: Effects on language and literacy development.(1), 31−41.

*Dickinson, D. K., & de Temple, J. (1998). Putting parents in the picture: Maternal reports of preschoolers’ literacy as a predictor of early reading.,(2), 241−261.

Dong, Y., Dong, W. Y., Wu, S. X. Y., & Tang, Y. (2020). The effects of home literacy environment on children's reading comprehension development: A meta-analysis.(2), 63−82.

Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, D. M. (2007).(4th ed.). Bloomington, MN: NCS Pearson, Inc.

Durkin, D. (1966).. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

*Evans, M. A., Shaw, D., & Bell, M. (2000). Home literacy activities and their influence on early literacy skills.,(2), 65−75.

Evans, M., Kelley, J., Sikora, J., & Treiman, D. (2010). Family scholarly culture and educational success: Books and schooling in 27 nations., 171−197.

Farkas, G., & Beron, K. (2004). The detailed age trajectory of oral vocabulary knowledge: Differences by class and race.,(3), 464−497.

*Farver, J. A. M., Xu, Y., Eppe, S., & Lonigan, C. J. (2006). Home environments and young Latino children’s school readiness.,(2), 196−212.

Fernald, A., Marchman, V. A., & Weisleder, A. (2013). SES differences in language processing skill and vocabulary are evident at 18 months.(2), 234−248.

*Fielding-barnsley, R., & Hay, I. (2012). Comparative effectiveness of phonological awareness and oral language intervention for children with low emergent literacy skills.,(3), 271− 286.

Finneran, D. A., Heilmann, J. J., Moyle, M. J., & Chen, S. (2020). An examination of cultural-linguistic influences on PPVT-4 performance in African American and Hispanic preschoolers from low-income communities.(3), 242−255.

*Foster, M. A., Lambert, R., Abbott-Shim, M., McCarty, F., & Franze, S. (2005). A model of home learning environment and social risk factors in relation to children’s emergent literacy and social outcomes.,(1), 13−36.

*Frijters, J. C., Barron, R. W., & Brunello, M. (2000). Direct and mediated influences of home literacy and literacy interest on prereaders’ oral vocabulary and early written language skill.,(3), 466−477.

*Froiland, J. M., Powell, D. R., Diamond, K. E., & Son, H. C. S. (2013). Neighborhood socioeconomic well-being, home literacy, and early literacy skills of at-risk preschoolers.,(8), 755−769.

Gettinger, M., & Stoiber, K. C. (2014). Increasing opportunities to respond to print during storybook reading: Effects of evocative print-referencing techniques.,(3), 283−297.

Gilkerson, J., Richards, J. A., & Topping, K. J. (2017). The impact of book reading in the early years on parent-child language interaction.,(1), 92−110.

*Gonzalez, J. E., Acosta, S., Davis, H., Pollard-Durodola, S., Saenz, L., Soares, D., … Zhu, L. (2017). Latino maternal literacy beliefs and practices mediating socioeconomic status and maternal education effects in predicting child receptive vocabulary.,(1), 78−95.

Gonzalez, J. E., Taylor, A. B., McCormick, A. S., Villareal, V., Kim, M., Perez, E., … Haynes, R. (2011). Exploring the underlying factor structure of the home literacy environment (HLE) in the English and Spanish versions of the Familia Inventory: A cautionary tale.(4), 475−483.

*Griffin, E. A., & Morrison, F. J. (1997). The unique contribution of home literacy environment to differences in early literacy skills.,(1), 233−243.

Hamilton, L. G., Hayiou-Thomas, M. E., Hulme, C., & Snowling, M. J. (2016). The home literacy environment as a predictor of the early literacy development of children at family-risk of dyslexia.,(5), 401−419.

Hart, B., & Risley, T. (1995).. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing.

*Hayes, N., Berthelsen, D. C., Nicholson, J. M., & Walker, S. (2018). Trajectories of parental involvement in home learning activities across the early years: Associations with socio-demographic characteristics and children’s learning outcomes.(10), 1405−1418.

Heath, R. W., Levin, P. F., & Tibbetts, K. A. (1993). Development of the home learning environment profile. In R. N. Roberts (Ed.),(pp. 91−132). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Hiebert, E. H. (2015). Changing readers, changing texts: Beginning reading texts from 1960 to 2010.,(3), 1−13.

Higgins, J. P. T., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J., & Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses.(7414), 557−560.

*Hindman, A. H. (2008).(Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Michigan.

Hindman, A. H., Connor, C. M., Jewkes, A. M., & Morrison, F. J. (2008). Untangling the effects of shared book reading: Multiple factors and their associations with preschool literacy outcomes.(3), 330−350.

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context.. Retrieved from http://scholarworks. gvsu.edu/orpc/vol2/iss1/8

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010).(Rev. 3rd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Hu, B. Y., Johnson, G. K., Teo, T., & Wu, Z. (2020). Relationship between screen time and Chinese children’s cognitive and social development.,(2), 183−207.

*Hubbs-Tait, L., Mulugeta, A., Bogale, A., Kennedy, T. S., Baker, E. R., & Stoecker, B. J. (2009). Main and interaction effects of iron, zinc, lead, and parenting on children’s cognitive outcomes.,(2), 175−195.

Huntsinger, C. S., Jose, P. E., Liaw, F.-R., & Ching, W. D. (1997). Cultural differences in early mathematics learning: A comparison of euro-american, chinese-american, and taiwan-chinese families.(2), 371−388.

Hussar, B., Zhang, J., Hein, S., Wang, K., Roberts, A., Cui, J., … Dilig, R. (2020).. https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2020144

Inkeles, A., & Sirowy, L. (1983). Convergent and divergent trends in national educational systems.(2), 303−333.

*Inoue, T., Georgiou, G. K., Parrila, R., & Kirby, J. R. (2018). Examining an extended home literacy model: The mediating roles of emergent literacy skills and reading fluency.,(4), 273−288.

*Iruka, I. U., Brown, D., Jerald, J., & Blitch, K. (2018). Early steps to school success (ESSS): Examining pathways linking home visiting and language outcomes.,(2), 283−301.

*Iruka, I. U., Dotterer, A. M., & Pungello, E. P. (2014). Ethnic variations of pathways linking socioeconomic status, parenting, and preacademic skills in a nationally representative sample.(7), 973−994.

Keller, H., Lamm, B., Abels, M., Yovsi, R., Borke, J., Jensen, H., ... Chaudhary, N. (2006). Cultural models, socialization goals, and parenting ethnotheories: A multicultural analysis., 155−172.

*Kelman, M. E. (2006).(Unpublished doctorial dissertation). Wichita State University.

Kirby, J. R., & Hogan, B. (2008). Family literacy environment and early literacy development.,(3), 112−130.

Klein, O., & Becker, B. (2017). Preschools as language learning environments for children of immigrants: Differential effects by familial language use across different preschool contexts.,, 20−31.

*Kluczniok, K., & Mudiappa, M. (2019). Relations between socio-economic risk factors, home learning environment and children’s language competencies: Findings from a German study.,(1), 85−104.

*Korat, O., Arafat, S. H., Aram, D., & Klein, P. (2013). Book reading mediation, SES, home literacy environment, and children’s literacy: Evidence from Arabic-speaking families.,(2), 132−154.

*Korucu, I., & Schmitt, S. A. (2020). Continuity and change in the home environment: Associations with school readiness., 97− 107.

*Krijnen, E., van Steensel, R., Meeuwisse, M., Jongerling, J., & Severiens, S. (2020). Exploring a refined model of home literacy activities and associations with children’s emergent literacy skills.(1), 207− 238.

*Ladd, M., Martin-Chang, S., & Levesque, K. (2011). Parents’ reading-related knowledge and children’s reading acquisition.(2), 201−222.

*Lambrecht, J., Bogda, K., Koch, H., Nottbusch, G., & Sporer, N. (2019). Comparing the effect of home and institutional learning environment on children’s vocabulary in primary school.(2), 86−115.

Laufer, B. (1998). The development of passive and active vocabulary in a second language: Same or different?,(2), 255−271.

*Lehrl, S., Ebert, S., & Rossbach, H. (2013). Facets of preschoolers' home literacy environments: What contributes to reading literacy in primary school? In M. Pfost, C. Artelt, & S, Weinert (Eds.),(pp.35−61)University of Bamberg press.

Leichter, H. J. (1984). Families as environments for literacy. In H. Goelman, A. Oberg, & F. Smith (Eds.),(pp. 38−50). London: Heinemann.

*Lee, Y.-J., Lee, J.-S., & Lee, J.-W. (1997). The role of the play environment in young children’s language development., 49−71.

Li, J. (2012).New Youk, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Liu, C., Georgiou, G. K., & Manolitsis, G. (2018). Modeling the relationships of parents’ expectations, family’s SES, and home literacy environment with emergent literacy skills and word reading in Chinese.,, 1−10.

*Lohndorf, R. T., Vermeer, H. J., Cárcamo, R. A., & Mesman, J. (2018). Preschoolers’ vocabulary acquisition in Chile: The roles of socioeconomic status and quality of home environment.,(3), 559−580.

*Manolitsis, G., Georgiou, G. K., & Parrila, R. (2011). Revisiting the home literacy model of reading development in an orthographically consistent language.,(4), 496−505.

*Manolitsis, G., Georgiou, G., Stephenson, K., & Parrila, R. (2009). Beginning to read across languages varying in orthographic consistency: Comparing the effects of non-cognitive and cognitive predictors.,(6), 466−480.

Marulis, L. M, & Neuman, S. B. (2013). How vocabulary interventions affect young children at risk: A meta- analytic review.,(3), 223−262.

Mayer, R. E.. (2003). The promise of multimedia learning: Using the same instructional design methods across different media.(2), 125−139.

McQuillan, J. (2006). The effects of print access and print exposure on English vocabulary acquisition of language minority students.,(1), 41−51.

*McTaggart, J. A. (2004).(Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Guelph.

*Meng, C. (2015). Home literacy environment and Head Start children’s language development: The role of approaches to learning.,(1), 106−124.

Mol, S. E., & Bus, A. G. (2011). To read or not to read: A meta-analysis of print exposure from infancy to early adulthood.,(2), 267−296.

Mol, S. E., Bus, A. G., de Jong, M. T., & Smeets, D. J. H. (2008). Added value of dialogic parent-child book readings: A meta-analysis.,(1), 7−26.

*Mol, S. E., & Neuman, S. B. (2014). Sharing information books with kindergartners: The role of parents’ extra- textual talk and socioeconomic status.,(4), 399−410.

Montag, J. L., Jones, M. N., & Smith, L. B. (2015). The words children hear: Picture books and the statistics for language learning.,(9), 1489− 1496.

Niklas, F., Nguyen, C., Cloney, D. S., Tayler, C., & Adams, R. (2016). Self-report measures of the home learning environment in large scale research: Measurement properties and associations with key developmental outcomes.,(2), 181−202.

Niklas, F., & Schneider, W. (2013). Home literacy environment and the beginning of reading and spelling.,(1), 40−50.

Pagani, L. S., Fitzpatrick, C., Barnett, T. A., & Dubow, E.. (2010). Prospective associations between early childhood television exposure and academic, psychosocial, and physical well-being by middle childhood.(5), 425−431.

Parmar, P., Harkness, S., & Super, C. M. (2004). Asian and Euro-American parents' ethnotheories of play and learning: Effects on preschool children's home routines and school behaviour., 97−104.

*Payne, A. C., Whitehurst, G. J., & Angell, A. L. (1994). The role of home literacy environment in the development of language ability in preschool children from low-income families.,(3-4), 427−440.

Pellegrini, A. D., Galda, L., Jones, I., & Perlmutter, J.. (1995). Joint reading between mothers and their head start children: Vocabulary development in two text formats.(3), 441−463.

Peterson, R. A., & Brown, S. P. (2005). On the use of beta coefficients in meta-analysis.(1), 175−181.

Puglisi, M. L., Hulme, C., Hamilton, L. G., & Snowling, M. J. (2017). The home literacy environment is a correlate, but perhaps not a cause, of variations in children’s language and literacy development.,(6), 498−514.

Raikes, H., Luze, G., Brooks-Gunn, J., Raikes, H. A., Pan, B. A., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., … Rodriguez, E. T. (2006). Mother-child book reading in low-income families: Correlates and outcomes during the first three years of life.,(4), 924−953.

*Ren, L., Hu, B. Y., & Wu, Z. (2019). Profiles of literacy skills among Chinese preschoolers: Antecedents and consequences of profile membership.,(2), 22−32.

*Ren, L., Hu, B. Y., & Zhang, X. (2021). Disentangling the relations between different components of family socioeconomic status and Chinese preschoolers’ school readiness.(1), 216−234.

Rideout, V. (2017).. San Francisco, CA: Common Sense Media. Retrieved May 3, 2020, from https://www. commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/uploads/research/csm_zerotoeight_fullreport_release_2.pdf

*Roberts, J., Jergens, J., & Burchinal, M. (2005). The role of home literacy practices in preschool children’s language and emergent literacy skills.,(2), 345−359.

*Rodriguez, E. T. (2008).(Unpublished doctoral dissertation). New York University.

*Rodriguez, E. T., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Spellmann, M. E., Pan, B. A., Raikes, H., Lugo-Gil, J., & Luze, G. (2009). The formative role of home literacy experiences across the first three years of life in children from low-income families.,(6), 677−694.

*Roth, F. P., Speece, D. L., & Cooper, D. H. (2002). A longitudinal analysis of the connection between oral language and early reading.,(5), 259−272.

Rothstein, H. R., Sutton, A. J., & Borenstein, M. (2006).. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons.

Scarborough, H., & Dobrich, W. (1994). On the efficacy of reading to preschoolers.,, 245− 302.

*Schlesinger, M. A., Flynn, R. M., & Richert, R. A. (2019). Do parents care about TV? How parent factors mediate US children’s media exposure and receptive vocabulary.,(4), 395−414.

*Schmerse, D., Anders, Y., Flöter, M., Wieduwilt, N., Roßbach, H., & Tietze, W. (2018). Differential effects of home and preschool learning environments on early language development.(2), 338−357.

*See, H. M. (2008).(Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Maryland.

*Sénéchal, M. (2006). Testing the home literacy model.,(1), 59−87.

*Sénéchal, M., & LeFevre, J. A. (2002). Parental involvement in the development of children’s reading skill: A five-year longitudinal study.,(2), 445−460.

*Sénéchal, M., & LeFevre, J. A. (2014). Continuity and change in the home literacy environment as predictors of growth in vocabulary and reading.,(4), 1552−1568.

*Sénéchal, M., LeFevre, J. A., Hudson, E., & Lawson, E. P. (1996). Knowledge of storybooks as a predictor of young children’s vocabulary.,(3), 520−536.

*Sénéchal, M., LeFevre, J.-A., Thomas, E. M., & Daley, K. E. (1998). Differential effects of home literacy experiences on the development of oral and written language.(1), 96−116.

*Sénéchal, M., Thomas, E., & Monker, J. A. (1995). Individual differences in 4-year-old children’s acquisition of vocabulary during storybook reading.,(2), 218−229.

*Shahaeian, A., Wang, C., Tucker-Drob, E., Geiger, V., Bus, A. G., & Harrison, L. J. (2018). Early shared reading, socioeconomic status, and children’s cognitive and school competencies: Six years of longitudinal evidence.,(6), 485−502.

Shu, H., Li, W., Richard, A., Ku, Y.-M., & Yue, X. (2002). The role of home-literacy environment in learning to read Chinese. In W. Li, J. S. Gaffney, & J. L. Packard (Eds.),(pp. 207−224). Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

*Silinskas, G., Torppa, M., Lerkkanen, M., & Nurmi, J. (2020). The home literacy model in a highly transparent orthography.(1), 80−101.

*Skwarchuk, S. L., Sowinski, C., & LeFevre, J. A. (2014). Formal and informal home learning activities in relation to children’s early numeracy and literacy skills: The development of a home numeracy model.,(1), 63−84.

Sosa, A. V. (2015). Association of the type of toy used during play with the quantity and quality of parent-infant communication.(2), 132−137.

*Sparks, A., & Reese, E. (2013). From reminiscing to reading: Home contributions to children’s developing language and literacy in low-income families.(1), 89−109.

Standing, E. M. (1957).New York, NY: Plume.

Stanovich, K. E., & West, R. F. (1989). Exposure to print and orthographic processing.(4), 402−433.

*Stephenson, K. A., Parrila, R. K., Georgiou, G. K., & Kirby, J. R. (2008). Effects of home literacy, parents’ beliefs, and children’s task-focused behavior on emergent literacy and word reading skills.,(1), 24−50.

Stipek, D., Milburn, S., Clements, D., & Daniels, D. H. (1992). Parents’ beliefs about appropriate education for young children.,(3), 293−310.

*Suggate, S. P., Schaughency, E. A., & Reese, E. (2011). The contribution of age and reading instruction to oral narrative and pre-reading skills.,(4), 379−403.

Super, C. M., & Harkness, S. (2002). Culture structures the environment for development., 270−274.

Switzer, G. E, Wisniewski, S. R, Belle, S. H, Dew, M. A, & Schultz, R. (1999). Selecting, developing, and evaluating research instruments.(8), 399−409.

Taylor, R. (1995). Functional uses of reading and shared literacy activities in Icelandic homes: A monograph in family literacy., 194−219.

Taylor, R. (1996).. Grandview, MO: Family Reading Resources.

Taylor, R. (2000).. Grandview, MO: Family Reading Resources.

Teale, W. H., & Sulzby, E. (1986). Emergent literacy as a perspective for examining how young children become writers and readers. In W. H. Teale, & E. Sulzby (Eds.).(pp. vii−xxv). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Teepe, R. C., Molenaar, I., Oostdam, R., Fukkink, R., & Verhoeven, L. (2017). Children’s executive and social functioning and family context as predictors of preschool vocabulary.,(7), 1−8.

Tomopoulos, S., Dreyer, B. P., Tamis-lemonda, C., Flynn, V., Rovira, I., Tineo, W., & Mendelsohn, A. L. (2006). Books, toys, parent-chikd interaction, and Development in young Latino children.,(2), 72−78.

*Torppa, M., Parrila, R., Niemi, P., Lerkkanen, M. K., Poikkeus, A. M., & Nurmi, J. E. (2013). The double deficit hypothesis in the transparent Finnish orthography: A longitudinal study from kindergarten to Grade 2.,(8), 1353−1380.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2019).. Retrieved July 3, 2020, from https://www-bls-gov.proxy. lib.umich.edu/charts/american-time-use/activity-by-parent.htm

van Ijzendoorn, M. H., Dijkstra, J., & Bus, A. G. (1995). Attachment, intelligence, and language: A meta-analysis.,(2), 115−128.

*Wang, H. H. (2015).(Unpublished doctoral dissertation)Syracuse University. New York.

Wasik, B. A., Hindman, A. H., & Snell, E. K. (2016). Book reading and vocabulary development: A systematic review.,, 39−57.

Weinberger, J. (1996).. London: Paul Chapman Publishing Ltd.

Whitehurst, G. J. (1993).. Stony Brook, NY: Author.

*Whitehurst, G. J., Arnold, D. S., Epstein, J. N., Angell, A. L., Smith, M., & Fischel, J. E. (1994). A picture book reading intervention in day care and home for children from low-income families.,(5), 679−689.

Whitehurst, G. J., & Lonigan, C. J. (1998). Child development and emergent literacy.,(3), 848− 872.

Wilkins, D. A. (1972).. London: Edward Amold.

*Willard, J. A., Agache, A., Jäkel, J., Glück, C. W., & Leyendecker, B. (2015). Family factors predicting vocabulary in Turkish as a heritage language.,(4), 875−898.

*Williams, K. E., Barrett, M. S., Welch, G. F., Abad, V., & Broughton, M. (2015). Associations between early shared music activities in the home and later child outcomes: Findings from the longitudinal study of Australian children., 113− 124.

World Bank. (2021). School enrollment, preprimary. Retrieved July 3, 2021, from https://data.worldbank.org/ indicator/SE.PRE.ENRR

*Wu, C.C. (2007).(Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Syracuse University. New York.

*Xiao, N., Che, Y., Zhang, X., Song, Z., Zhang, Y., & Yin, S. (2020). Father−child literacy teaching activities as a unique predictor of Chinese preschool children's word reading skills.(4), 1−16.

Xu, Y., & Liu, L. (2020). Examining sociocultural factors in assessing vocabulary knowledge of children from low socio-economic background.,(15), 1−11.

*Zhang, S. Z., Georgiou, G. K., Xu, J., Liu, J. M., Li, M., & Shu, H. (2018). Different measures of print exposure predict different aspects of vocabulary.,(4), 443−454.

Zucker, T. A., Cabell, S. Q., Justice, L. M., Pentimonti, J. M., & Kaderavek, J. N. (2013). The role of frequent, interactive prekindergarten shared reading in the longitudinal development of language and literacy skills.,(8), 1425−1439.

Associations between home literacy environment and children’s receptive vocabulary: A meta-analysis

LIU Haidan1, LI Minyi2

(1Faculty of Education, Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an 710062, China)(2Faculty of Education, Beijing Normal University, Beijing 100875, China)

A large body of studies have shown that home literacy environment (HLE) can significantly promote children’s receptive vocabulary development. However, the blurry operationalization of HLE’s construct and the inconsistency of effect sizes (ESs) in recent studies have made it difficult to understand what really works for children’s receptive vocabulary development at home. This meta-analysis systematically reviewed empirical studies published from 1990 to 2021 to clarify HLE constructs, investigate the main effects, and explore potential moderators. A comprehensive search of peer-reviewed published research resulted in 84 articles. Results of random effects model indicated a significant, moderate relation between HLE and children’s receptive vocabulary development,= 0.31,< 0.01. Moderator analysis showed that the ESs of HLE decreased significantly across time periods, while the ESs of the frequency of shared reading were stable during past 30 years. The ESs of HLE obtained by questionnaires and the Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment did not lead to significant differences, while thoseof the frequency of shared reading obtained by Children’s Title Checklist were significantly higher than those obtained by questionnaires. No moderating effects of cultural backgrounds or child’s age were detected. Findings suggest that there is a need to refine the conceptual framework and measurement methods of HLE, especially paying more attention to social-economic and cultural influences.

Home literacy environment (HLE), shared reading, receptive vocabulary, meta-analysis

2020-11-16

李敏谊, E-mail: minyili@bnu.edu.cn

B844