Ethical Problems in MTI Students’Escort Interpreting from the Perspective of Chesterman’s Models on Translation Ethics

2022-03-03ZHANGHai-long,SUNJing

ZHANG Hai-long,SUN Jing

The professionalization of translation has been discussed by many scholars in recent years, which has inspired the intense discussion of translation ethics. Drawing upon Chesterman’s models on translation ethics, this paper intends to examine the ethical problems in MTI students’ escort interpreting for Vanuatu Sport Technical Assistance Project for the Pacific Mini Games in 2017 and China-ASEAN International Capacity Cooperation Forum in 2016. The data was collected by the methods of participant observation and informal interviews in the process of the two interpreting projects, especially the six-month assistance project. The ethical problems in the escort interpreting and the reasons that caused the problems were analyzed through case study. It is found that the major ethical problems that occurred are related to the ethics of communication, the norm-based ethics, and the ethics of commitment. These ethical problems were mainly related to the student escort interpreters’ language proficiency, professional qualities, and intercultural / interpersonal communication competence. Some solutions are suggested based on Chesterman’s models on translation ethics. It is hoped that the research findings can provide some references to the implementation of the similar interpreting programs in the future, and enhance interpreting teaching and training programs.

Keywords: translation ethics, escort interpreting, Chesterman’s models on translation ethics, intercultural communication

Introduction

With the development of translation and interpreting research, there has been a shift of translation studies from prescriptive study to descriptive study. Prescriptive translation studies focus on the linguistic perspective, emphasizing the importance of lexicology, syntax, semantics, stylistics and etc.. However, with the gradual exposures of factors concerning cultures, politics, rights and genders, we are aware of the limitations of prescriptive translation studies which ignore the social and cultural environment. So, the shift of translation studies requres more attention on non-linguistic aspects, from the textual level to the broader social and cultural level (Chen Jinjin, 2012). In recent years, the professionalization of translation has been discussed by many scholars, which has inspired the intense discussion of translation ethics.

Interpreting practice in the real situation has been given much attention in Master of Translation and Interpreting (MTI) program. Students are required to participate in interpreting activities for international events organized by the school, institutions or companies. It is a good opportunity for MTI students to apply the theories to the practice and improve their interpreting skills. However, it is challenging for most students. Having learned prescriptive principles on translation and interpreting, students tend to focus on the language itself, without paying much attention to cultural differences, social backgrounds, and interpreters’ own positions in interpreting activities. When unexpected conflicts or offence occur, they feel lost and are not able to handle the situation properly. They can hardly identify the reasons for the communication breakdown. These problems deserve our attention. Thus, to encourage interpreters’ reflection on translation ethics in the process of interpreting can help them better position themselves in interpreting activities. It is necessary for scholars to study ethical problems, which will be beneficial to the practice and future research of translation and interpreting.

Literature Review

The term “translation ethics” was initially proposed by Antoine Berman in 1980. According to Berman(1992), “the ethics of translation consists of bringing out, affirming and defending the pure aims of translation”, and “it consists of defining what “fidelity” is” (p. 5). Berman (2009) stated that a translator will start to take responsibilities when he or she accepts or engages himself or herself into a translation activity, and a translator is a social man who has restrictions on some kinds of ethics.. Following Berman, more scholars like Lawrence Venuti, Anthony Pym and Andrew Chesterman made great contributions to the studies of translation ethics. Anthony Pym (2001), the initiator of “the return to ethics”, stated that an ethical translator was supposed to determine “how to translate”, taking the clients’ requirements and the target readers’ expectations into consideration. Besides, Pym (1997) first proposed the term “interculturality”, which meant that the ethics of translation had turned from the traditional perspective of fidelity into the perspective of cultural communication. Andrew Chesterman (2001) agreed with them, and claimed that translation was an occupation and it needed its own professional principles and rules. He further proposed his “Five Models” on translation ethics, which were relatively more systematic, descriptive, and influential.

In China, research on translation ethics is mainly the introduction to the international studies, theoretical discussions on translation ethics and literature review. Some scholars such as Wang Dazhi (2012), Luo Xianfeng (2009) and Chen Zhendong (2010) have researched, emphasizing the subjectivity and responsibility of translators and the importance of ethics in the studies on translation. Chesterman’s Five Models on translation ethics were discussed by many Chinese scholars (Chen Shunyi, 2015; Guo Lei, 2014), and were applied to the research mainly in translation (Chen Furong, Liu Hao, 2010; Hou Li, Xu Luzhi, 2013; Ouyang Dongfeng, Mu Lei, 2017). However, not much research has been done on ethics in interpreting. The study on escort interpreting ethics remains an area which is not explored sufficiently.

Andrew Chesterman’s “Five Models” on Translation Ethics

Andrew Chesterman’s “Five Models” on translation ethics include the ethics of representation, ethics of service, ethics of communication, norm-based ethics and ethics of commitment. According to Chesterman (2001), the ethics of representation is to study the relationship between the source text and the target text, and the writer and the translator, emphasizing the representation of intentions of the source text and the writer. The ethics of service intends to analyze the relationship between the translation or translator and the user of the target text. Translators are demanded to translate from the perspective of users (readers, listeners and clients), and to keep the requirements and intentions of users or clients in their mind, serving both the original writer and the users or clients of the target text. The ethics of communication intends to analyze the relationship and interaction among the target text or translator, the source text or writer, and the user of the target text. The translator is like a bridge, connecting the original writer or source text and the user of the target text in a proper way, considering the effects of the target text in the culture of target language, so that it can achieve the goal of transferring information by breaking the limitations on languages, cultures and societies. The norm-based ethics includes the expectancy norms and the professional norms. The expectancy norms refer to the acceptability of the target text, while the professional norms refer to the acceptability of translators’ translation behaviors to each party. The professional norms are accountability norms, communication norms and relation norms. Meanwhile, he proposed four targeted values on translation ethics, including clarity, truth, trust and understanding. Clarity refers to the precise interpretation of the source text, and the value of truth requires translators to lean close to the meanings of the source text and the intentions of the original writer, so that the expectancy norms and accountability norms can be satisfied. The values of trust and understanding refer to the reliance and proper understanding among the original writer, translator and the user or client of the target text, so that the communication norms and relation norms can be satisfied properly. The norm-based ethics is a kind of conclusion and restriction of other principles on translation ethics. The ethics of commitment is proposed based on the former four models of translation ethics. Translation, as an occupation, should have its own codes of ethics. The ethics of commitment shows the responsibilities and obligations as well as the professional standards of translators. Translators need to follow the professional ethics, trying to be a translator with morality, conscientiousness and responsibility.

The Study

This paper investigates the ethical problems in the process of MTI students’ escort interpreting for two programms based on Chesterman’s “Five Models” on translation ethics. The ethical problems in the escort interpreting and the reasons that cause the problems are analyzed through case study. This paper intends to answer two questions: (1) Are there any ethical problems in the process of escort interpreting? If yes, what types are they? (2) What are the reasons for those ethical problems?

The data for this study is collected from two programs, which include Vanuatu Sport Technical Assistance Project for the Pacific Mini Games in Kunming, Yunnan Province (2017) and China-ASEAN International Capacity Cooperation Forum in Tuole, Guizhou Province (2016) . Vanuatu Sport Technical Assistance Project was sponsored by the Ministry of Commerce of China, aiming to provide technical assistance to Vanuatu in terms of sports. It was implemented at Yunnan Provincial Sport Training Base and lasted for six months from April to September in 2017. 66 athletes and coaches from nine sports teams in Vanuatu were invited for the assistance program. 12 MTI students in Interpreting program from a university were assigned the tasks to provide escort interpreting mainly for four-hour daily sports training and their daily life at the training base. China-ASEAN International Capacity Cooperation Forum in 2016 was jointly organized by the local government of Panxian county in Guizhou province and the China-ASEAN Business Council, aiming to strengthen the bilateral trade and promote the sustainable development between China and ASEAN countries. The forum was held in Tuole of Guizhou province on November 17, 2016, with 303 participants from China and other 10 countries including Laos, Myanmar, Cambodia, Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei, Singapore and the Philippines. Around 15 MTI students in Interpreting program from the same university were sent there working for four days as escort interpreters and helping with the foreign guests’ communication at the airport, in daily life, and at different places of tourist attraction.

Data Collection and Analysis Methods

Participant observation and interviews were the major methods used to collect the data. Participant observation is conducted to examine the phenomenon or people’s behavior in the process of escort interpreting. The first author of this paper participated in the escort interpreting activities for the two programs as both interpreter and observer. As an escort interpreter, he needed to fulfil the task of interpreting while as an observer, he needed to collect the data from observation. His role of the escort interpreter makes data collection more convenient and feasible. He made observations and took field notes at the sites while working, around 4 hours each weekday. The field notes focus on interpreting related activities, including the interpreters’interpretation, body language, behavior, attitides, their remarks on their accomplished work, and the speakers or listeners’ responses.

For the first program, escort interpreting and observation were proceeded most of the time in the boxing venue of the training base because it was convenient for the author as both an observer and one of the two escort interpreters responsible for the communication among 23 boxing players and two coaches from Vanuatu, two Chinese coaches, and one Chinese team manager. For the second program, escort interpreting and observation were conducted for four days before, during and after the forum. The first author of the paper acted as both an observer and one of the two escort interpreters helping with the communication between six Philippine guests and two Chinese student volunteers accompanying them at the hotel, scenic spots and the convention center.

Ten escort interpreters who participated both programs were interviewed later one by one while the interviewer took notes. Six interview questions were designed to collect the information on the student interpreters’ awareness on translation ethics, the major problems they encountered during their escort interpreting, and the possible solutions to the problems.

The method used for analysis is case study. Typical cases related to ethical problems were selected and categorized into different types based on Chesterman’s Five Models on translation ethics. Further analysis was made to examine whether the escort interpreters’ performance is in conformity with Chesterman’s five models respectively.

Results and Discussion

The data collected from observation and interviews were analyzed from the perspective of Chesterman’s“Five Models” on translation ethics, which include the ethics of representation, the ethics of service, the ethics of communication, the norm-based ethics and the ethics of commitment. Based on the analysis of the observation notes and the answers provided to the interview questions, it is found that while the ethics of representation and the ethics of service were most often represented in MTI students’ escort interpreting, there exists inconformity to the ethics of communication, the norm-based ethics and the ethics of commitment,, which were the major ethical problems that occurred in the escort interpreting. These will be further discussed in the following.

The analysis results show that both the ethics of representation and the ethics of service were reflected or represented in the process of MTI students’ escort interpreting. For the first interview question “what are the vital elements do you think in escort interpreting?”, nearly 70% of the interviewees thought that fluency, effectiveness of interpreting, and comprehensive abilities were the crucial elements of escort interpreting, which stress language ability. Fluency and effectiveness of interpreting represent the ethics of service while comprehensive abilities are related to the ethics of representation, which emphasizes the representation of intentions of the source text and the author. From the observation, most MTI students were aware of the ethics of representation and the ethics of service, and made great efforts to show their fidelity to the speakers as well as to the listeners trying to serve both parties in their escort interpreting.

However, some problems occurred in MTI students’ escort interpreting, which were analyzed and categorized respectively as inconformity to the ethics of communication, the norm-based ethics and the ethics of commitment based on Chesterman’s five models. The first ethical problem identified was the inconformity to the ethics of communication in the escort interpreting. According to the analysis of the answers to the interview questions, nearly 90% of the student interpreters said that it was common for them to miss some information during the interpreting process even if they had the awareness and intention to represent completely what the speakers said. The information missed was most often technical terms and something they could not understand or identify. Sometimes they misinterpreted what the speaker said without awareness until conflicts occurred. This gap and misinterpretation resulted in their misleading of the conversation and hindered the communication as they admitted. Thus, MTI students’ interpreting failed to conform to the ethics of communication. They did not prepare themselves well enough professionally and culturally, overlooking the different social and cultural backgrounds of the participants in the conversation while interpreting. The following examples selected from Vanuatu Sport Technical Assistance Program are used to illustrate it.

Example (1)

The Chinese manager said: “我們体育基地的食堂不允许过量取餐,而且饮品每位运动员也只能喝一瓶,我们是有数量的.”

Interpreter A interpreted: “In the dining hall of the training base, players are not allowed to take too much food, and for those drinkings, each player can only drink one bottle, we have a certain number on them.”

The Vanuatu manager: … (The Vanuatu manager felt confused about the interpretation and gave no responses.)

Interpreter B added: “Because in the Chinese traditional culture, we are not allowed to waste food. For those players, they can take food for several times, but they are not allowed to take too much for one time to avoid waste. And for those drinkings, we have to make sure that each player can have one, so we distribute them by the number of our players.”

Then the Vanuatu manager nodded and said: “OK, I get it, I will tell my players about this.

In this example, the Vanuatu manager felt confused about such a rule at the buffet when hearing Interpreter A’s literal interpretations “not allowed to take too much food” for “不允许过量取餐”, and “have a certain number” for “有数量的”. Obviously, these inaccurate interpretations caused some misunderstanding that there was a limit on the supply of food. Besides, a buffet is usually a meal at which people serve themselves and are free to take whatever they need. That was why the Vanuatu manager could hardly understand this rule and felt puzzled. In China, such kind of reminder (warning) is very common at the buffet or hotel, and is usually displayed to prevent some people from taking too much food, or more specifically taking more food than they need. So, Interpreter B explained further emphasizing that this reminder was meant to avoid the wasting of food, which help resolve the confusion and made the communication go smooth. From Interpreter A’s inaccurate interpreting, we can see that he failed to convey the actual meaning the Chinese manager intended (not taking more food than one needs), and failed to be a bridge connecting the two parties due to the lack of cultural knowledge and sensitivity to intercultural issues, which led to the inconformity to the ethics of communication. Although the involved student interpreter claimed in the interview that he had the awareness of making the communication effective, his actual interpreting failed in the communication.

Example (2)

In the welcome ceremony of the cooperation forum, an official from the local government was having a conversation with a guest from the Philippines in private. The following is quote from their dialogue.

The official said: “你好,我是来自当地政府某某部门的李某某,欢迎你的到来.”

The student interpreter interpreted it into: “this is Mr. Li, he is showing his warm welcome to you.”

The foreign guest responded: “thank you.”

In this example, the student interpreter carelessly omitted the title of the local official in his interpreting, which brought no further communication between the two speakers because the Philippine guest had no idea who this speaker was, and took him as some Chinese who just wanted to show him his welcome like many other Chinese people do. So the Philippine guest simply replied “thank you”. The student interpreter’s neglecting the title of the local official on a formal occasion was obviously a serious mistake in such an international event, which aims to strengthen the cooperation with different countries in business and trade. It hindered their follow-up conversation and made their communication less effective. So, the student interpreter’s omission of the key information of identity or status in an important social setting did not conform to the ethics of communication.

The second ethical problem was the inconformity to the norm-based ethics in the escort interpreting. According to Chesterman (2001), the norm-based ethics emphasizes the acceptability of the target text and the acceptability of translators’ translation behaviors. Clarity, truth, trust and understanding are the four targeted values on translation ethics. Through observation, it is found that quite a few student interpreters simply interpreted literally what the speakers said without caring about the acceptability of their interpretation. It happened that when interpreting the terms in sports or something that requires technical knowledge, the student interpreters did not know the terms nor made any explanations on what they interpreted, which made the listeners confused. The inconformity to the norm-based ethics is illustrated in the following examples selected from Vanuatu Sport Technical Assistance Program.

Example (3)

During the boxing training, the coach always said “空击” in Chinese, which was one of many boxing practices. Interpreter C interpreted it into “air strike”, which made all boxing players confused. They did not know what to do when they heard the interpretation. After checking, Interpreter B interpreted “空擊” into “shadow boxing”, which could make all the players understand clearly and help the training move on smoothly.

In the above example, Interpreter C interpreted “空擊” into “air strike”, which made all boxers confused. This interpretation could not be accepted nor understood in the field of boxing as it was the student interpreter’s misunderstanding. According to Chesterman (2001), there are four targeted values on the norm-based ethics including clarity, truth, trust and understanding. Clarity refers to the precise interpretation of the source text, and the value of truth requires translators to lean close to the meanings of the source text and the intentions of the original writer. Apparently, Interpreter C did not show the values of clarity and truth, and did not take acceptability of his interpretation into consideration, which leads to the inconformity to the norm-based ethics in the student interpreter’s interpreting. According to the Collins dictionary, “air strike” refers to an attack by military aircraft in which bombs are dropped. So, all the boxers felt confused when hearing “air strike”. After checking, Interpreter B offered the correct interpretation “shadow boxing”, which was acceptable for all the boxers.

Example (4)

During the training, the Chinese coach often repeated the word “严谨” to guide the boxers on their boxing skills when the boxers were trained to give punches, do the blocking drills, and some other practices. Interpreter D always interpreted it into “preciseness” without any changes in different situations.

In the above example, the Chinese coach often used the same word “严谨” in different kinds of practices, but the meanings were different. When the coach said “严谨” in the practice of giving punches, he meant that all the boxers needed to give punches in a proper and powerful way. When the Chinese coach said “严谨” in the practice of blocking, he meant that all the boxers needed to find a perfect way to protect the target points from punching by their opponents. However, the involved student interpreter failed to use appropriate words and express different meanings in different contexts. According to Chesterman (2001), the norm-based ethics focuses on the values of trust and understanding, which refer to the reliance and proper understanding among the speaker, interpreter and the listener of an interpreting. In this example, the student interpreter did not get the real meaning of what the speaker had said, nor made his interpretation comprehensible and acceptable in different contexts. As a result, it was hard for listeners to trust and understand the interpretation as it was not accurate and appropriate. This kind of interpreting with no consideration of the contexts failed to conform to the norm-based ethics.

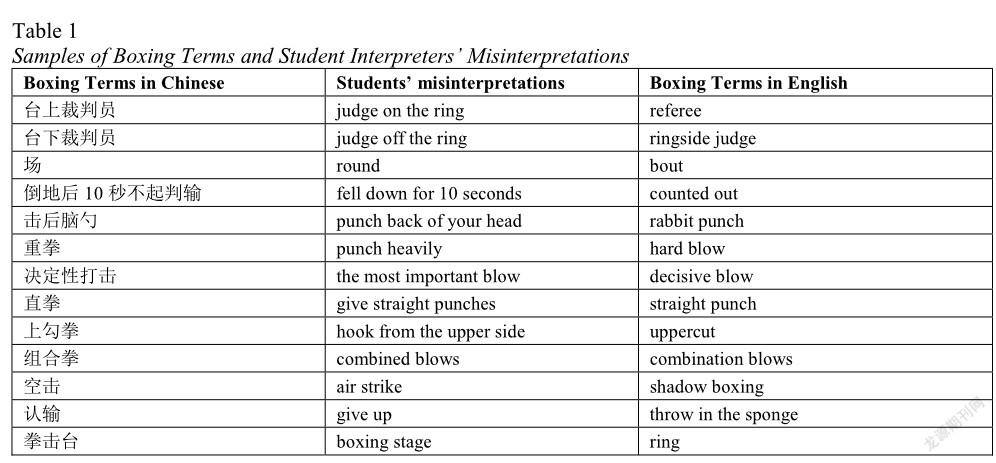

More examples are listed in the following table, in which students’ interpreting of technical terms in boxing failed to conform to the norm-based ethics. The boxing terms in English were later offered by the Vanuatu coaches when they were inquired.

The third ethical problem was the inconformity to the ethics of commitment in the escort interpreting. According to Chesterman (2001), the ethics of commitment emphasizes the responsibilities and obligations as well as the professional standards of translators. Translators need to observe the professional ethics, trying to be a translator with morality, conscientiousness and responsibility. However, most student interpreters held the view that all they need to do is only interpreting itself without caring much about other things involved, such as the role an interpreter is supposed to play, attitudes in working, social responsibility, and professional ethics. Thus, some student interpreters did not take their responsibilities seriously. Making mistakes in interpreting was very common and was not taken seriously by the student interpreters. In some situations, they did not know how to express clearly and appropriately, and behave in a professional way, which made the clients feel offended. Their inconformity to the ethics of commitment is illustrated in the following example selected from China-ASEAN International Capacity Cooperation Forum.

Example (5)

(The conversation took place in a hotel)

The Philippine guest asked: “I want to switch to BBC program, can you help me?”

The student interpreter answered (after trying): “I’m sorry, there is no BBC program here.”The Philippine guest explained: “But I just switched to it yesterday in the other hotel by myself. It must have BBC program, it’s just because you can’t switch it on.”

The student interpreter said: “I’m sure that the BBC program you mention can not be found here.”

The Philippine guest said (angrily): “Then you can go, I can fix it by myself.”

The student interpreter responded (angrily): “Oh, you are great. Good luck to you!”

(then the student interpreter left immediately)

In this example, the student interpreter apparently showed her dissatisfaction, impatience and even anger with the Philippine guest by saying “oh, you are great. Good luck to you!” before she left. This kind of expression filled with sarcasm was very impolite or rude in the situation. She failed to conform to the ethics of commitment as an escort interpreter who is supposed to provide assistance when needed. Her attitudes and behavior revealed the lack of professional qualities that the ethics of commitment requires. In addition, the student interpreter was not perceived by the Philippine guest as a person of good character because of her rude way of expressing herself. The communication broke down in the end. The suggested way to fix the problem for this case is to give some further explanation on why BBC program was not available here in this hotel and to fulfil the tasks in a better way. Interpreters need to follow the professional ethics, trying to be an interpreter with morality, conscientiousness and responsibility based on Chesterman’s translation ethics (2001),

Example (6)

The day before the forum started, all the student escort interpreters were traveling from from Kunming to Guiyang for training, and then to Tuole for the reception work. Due to the busy schedule, they did not get the time to eat the whole day. Since more international guests were arriving at night, the students were required to assist them to check in. At around 22:00, Interpreter E started to assist one Philippine guest to check in. An hour later, while the Philippine guest was still checking the facilities in the newly renovated room, Interpreter E asked: “If you do not need my help, will I go to have dinner? I have not eaten anything till now.” In response, the Philippine guest answered angrily: “you can go, I don’t need you any more.” The student interpreter wanted to explain, but the Philippine guest refused to listen. Then the student interpreter just left, leaving the student housekeeper and the Philippine guest in the house. As a result, the manager had to send Interpreter B to the room and provide assistance.

In this case, the student interpreters’ responsibility was to ensure the daily routines go smoothly and also make sure that the international guests were satisfied with everything related to the forum. However, there was a conflict in the communication between the student interpreter and the Philippine guest. On the student’s part, she did not eat the whole day and had every reason to ask for leave when she felt there was no more work for her to do. On the Philippine guest’s part, she believed that the escort interpreter was there doing her job without knowing much about the student’s situation. The point was that the student interpreter assumed that the guest did not need her help, and did not express herself properly. She made the request by using “will I...” instead of“May I...” or “Would you mind...”, which may sound more polite when one asks for permission. As a result, the Philippine guest felt offended by the student interpreter’s way of talking and her request for leave when she actually needed the student’s help. From this aspect, the student interpreter lacked communication skills and did not complete her task, which did not conform with the ethics of commitment. The suggested way would be to make the request in a more polite way, giving clear explanation, or to get some other interpreter there to help. Another suggestion is given to the host of the forum that some arrangement be made for the student interpreters to have meals.

Conclusion

This paper examines the ethical problems in MTI students’ escort interpreting for two programs drawing upon Chesterman’s models on translation ethics. The research results show that most of MTI students were aware of the importance of the ethics of representation and the ethics of service, and made great efforts to do well in their interpreting. However, some MTI students’ escort interpreting and behaviors did not conform to the ethics of communication, the norm-based ethics, and the ethics of commitment. The reasons to cause these ethical problems are mostly related to students’ language proficiency, professional qualities, and intercultural / interpersonal communication competence. Besides, the importance of translation and interpretation ethics is not given enough attention in the teaching and training of student interpreters.

The research findings can help develop MTI students’ awareness of translation ethics and encourage them to take the initiative in conforming to professional norms and principles, and become professional. The research findings can also provide some references to the implementation of the similar interpreting programs in the future, and enhance interpreting teaching and training programs.

For the limitation, the data was collected through observation, interviews, and in the form of field notes rather than recording, which may result in loss of information or inaccuracy of some of what was said and interpreted at the moment in the situation.

References

Berman, A. (1992). The experience of the foreign: culture and translation in romantic Germany. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Berman, A. (2009). Toward a translation criticism. Ohio: The Kent State University Press.

Chesterman, A. (2001). Proposal for a hieronymic oath. The Translator, 2, 139 -154.

Pym, A. (1997). Pour une ethique du traducteur. Arrsa et Ottawa: Artois Presses Université et Presses de 1 ’Universitéd’ Ottawa.

Pym, A. (2001). Introduction: the return to ethics in translation studies. The Translator, 2, 129-138.

陳芙蓉, 刘浩. (2010). 翻译职业化视角下的翻译伦理建设. 安徽工业大学学报, (6): 85-87.

陈金金. (2012). 切斯特曼五大翻译伦理模式的补充与改进 (上海外国语大学).

陈顺意. (2015). 论翻译伦理-基于切斯特曼翻译伦理的思考. 内蒙古农业大学学报, (3), 109-113.

陈振东. (2010). 翻译的伦理:切斯特曼的五大伦理模式. 国外理论动态, (3), 85-88.

郭磊. (2014). 安德鲁·切斯特曼翻译伦理模式透视. 兰州文理学院学报, (6), 100-103.

侯丽, 许鲁之. (2013). 从Andrew Chesterman的五个翻译伦理模式谈译者主体对翻译理的坚守. 外国语文, (6), 133-136.

骆贤凤. (2009). 中西翻译伦理研究述评. 中国翻译, (3), 13-17.

欧阳东峰, 穆雷. (2017). 论译者的翻译伦理行为选择机制. 外国语文, (4), 119-126.

王大智. (2012). 翻译与翻译伦理. 北京: 北京大学出版社.

猜你喜欢

杂志排行

Journal of Literature and Art Studies的其它文章

- The Latest Development of Ethical Literary Criticism in the World

- Analyzing Darcy’s Pride and Change from a Naturalistic Point of View

- Barbara Longhi of Ravenna:A Devotional Self-Portrait

- Jewish Sources for Iconography of the Akedah/Sacrifice of Isaac in Art of Late Antiquity

- The Aesthetic Reception of Poetry Through Painting:“After Apple-Picking”as an Example

- The Media Fusion and Digital Communication of Traditional Murals—Taking the Exhibition of the Series of Tomb Murals in Shanxi During the Northern Dynasty as an Example