Barbara Longhi of Ravenna:A Devotional Self-Portrait

2022-03-03LianaDeGirolamiCheney

From the variety of types of portraiture, there evolved the imaging of a self-portrait as we see in Saint Catherine of Alexandria by Barbara Longhi of Ravenna (1552-1638). The self-portrait is a unique work of art, an intimate record of a sitter’s personality. It is an acknowledgment of worth, an exercise in technique, and a designator of era, style, and likeness. The self-portrait can be a study in expression, an impersonation of a virtue, or a document in a history of aging. As William Shakespeare noted in Hamlet, “[The self-portrait is] to show virtue her own feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure.” In the sixteenth-century in Italy, artists often included themselves or their self-portraits in religious and secular scenes as a type of signature, as seen in the paintings of the Longhi family. In their many depictions of Saint Catherine of Alexandria, the Longhis composed two types of such images: a single—solo—image of the saint; and also her presence in a group with saints—a theme known as holy conversation. In her paintings, Barbara Longhi preferred to depict the solo image of Saint Catherine of Alexandria, using herself as a model for the figure of the saint or as a muse impersonating or personifying the saint’s virgo virtue. This essay is composed of two parts: (1) a brief explanation of the meaning of self-portraits in sixteenth-century Italy; and (2) a study of Barbara Longhi’s self-portraits as Saint Catherine of Alexandria.

Keywords: Barbara Longhi, Ravenna, Saint Catherine of Alexandria, self-portrait, personification, mirror, virgo, Christian symbolism, Mannerism, Tridentine Reform

Self-Portraits in Sixteenth-Century Italy

The self-portrait is a unique work of art, an intimate record of a sitter’s personality.1 It is an acknowledgment of worth, an exercise in technique, and a designator of era, style, and likeness. The self-portrait can be a study in expression, an impersonation of a virtue, or may be a document in a history of aging, “to show virtue her own feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure.”2

In part, the self-portrait is a revelation and a confession of the self. It is a declaration of who the painter is and how the artist wants to be seen: as a persona—a personification by the depiction of attributes—or artistic occupation, demonstrated by the depiction of materials used in the profession—media surfaces, pencils, brushes, color pigments, inks—and including a mirror. Dependence on the mirror presents the painter with a challenging dilemma, since the reflected image is reversed. Unless the artist uses a second mirror to right the reversal, the self-portrait is, in a sense, a counterfeit, e.g., Self-Portrait of 1646 by Johannes Gumpp, an Austrian painter residing in Florence during the seventeenth century (Figure 1).

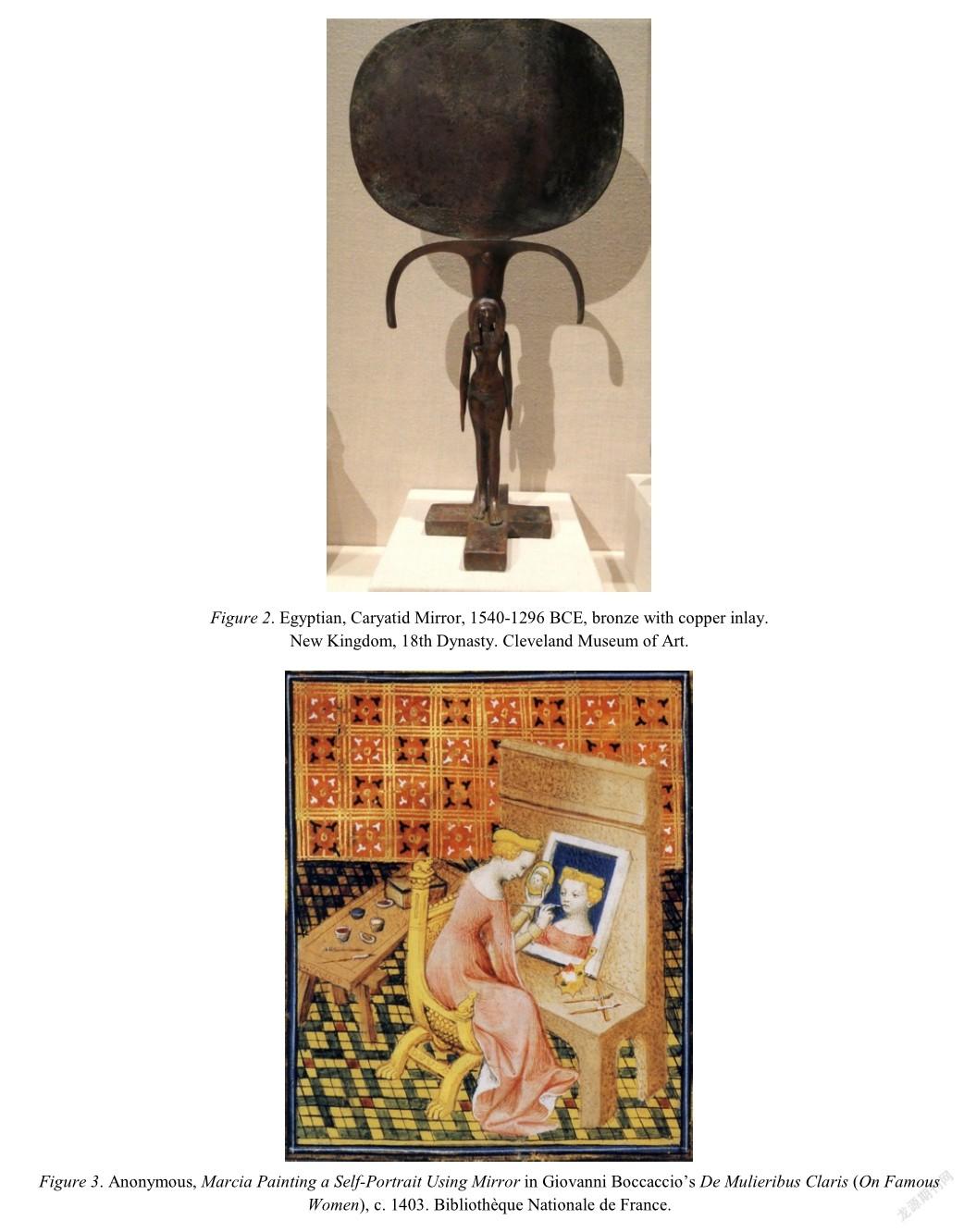

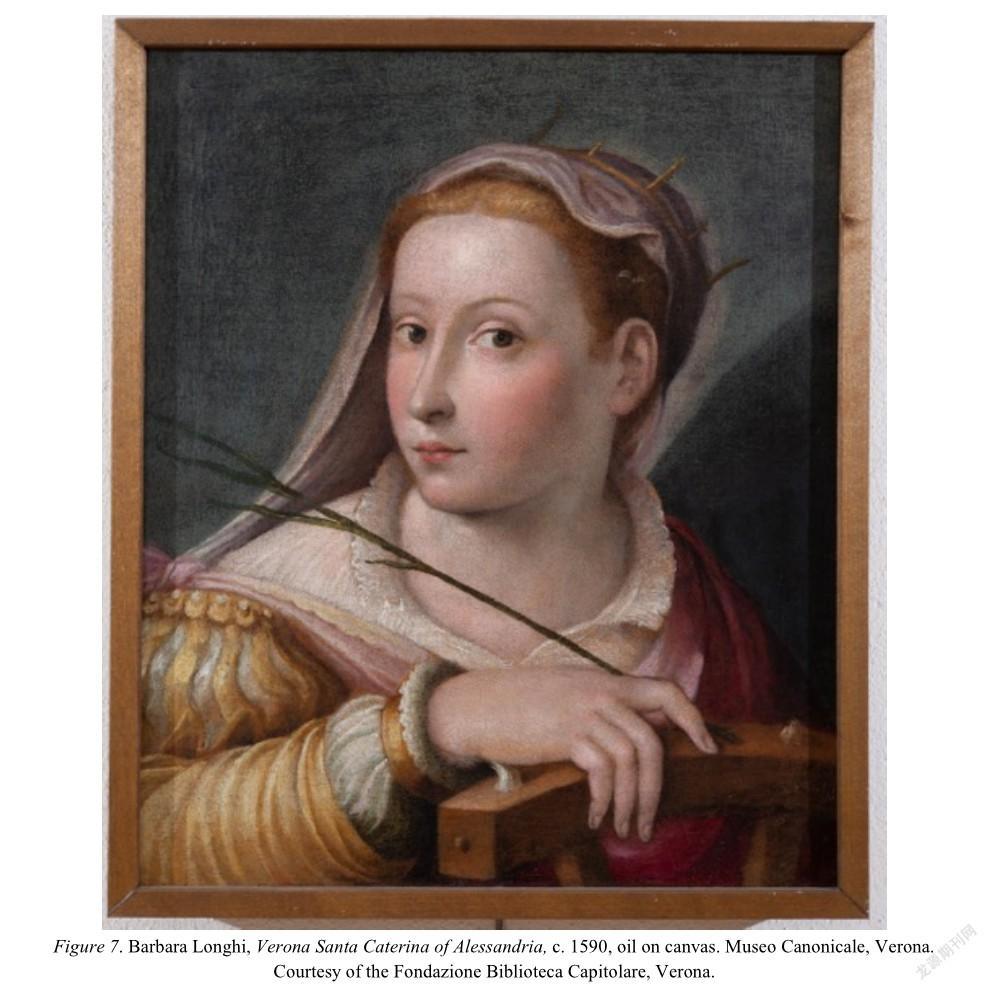

Tracing the role of the mirror in producing a likeness of the artist is challenging because of the limited historical and visual documentation. In Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Greek, Etruscan, and Roman times, polished metal “mirrors” provided only indistinct reflections (Figure 2). Although the face can be mirrored in smooth water, as with Narcissus, leaning over a pool to see one’s features is hardly a convenient posture for painting.3 Thus artists before the invention of the mirror lacked an essential tool to create an accurate self-image—a significant reason why there are so few self-portrayals from Antiquity and the Early Christian to the medieval periods (Figure 3).

Historically, the mirror provided the painter with an invaluable image, the reflection of the self, which the artist used to immortalize the self. Until its manufacture in Venice around 1300, the glass mirror as we know it today did not exist. Venetian glass mirrors were of circular format, similar to French ivory mirrors. In thirteenth-century Paris, mirrors were produced with two reflecting surfaces: clear glass or polished metal for mirroring on the recto; and on the verso beautifully decorated with an ivory setting.4 It is interesting to note that in ancient China, the idea of the mirror was registered on oracle bones and bronzes in the eleventh century BCE.5

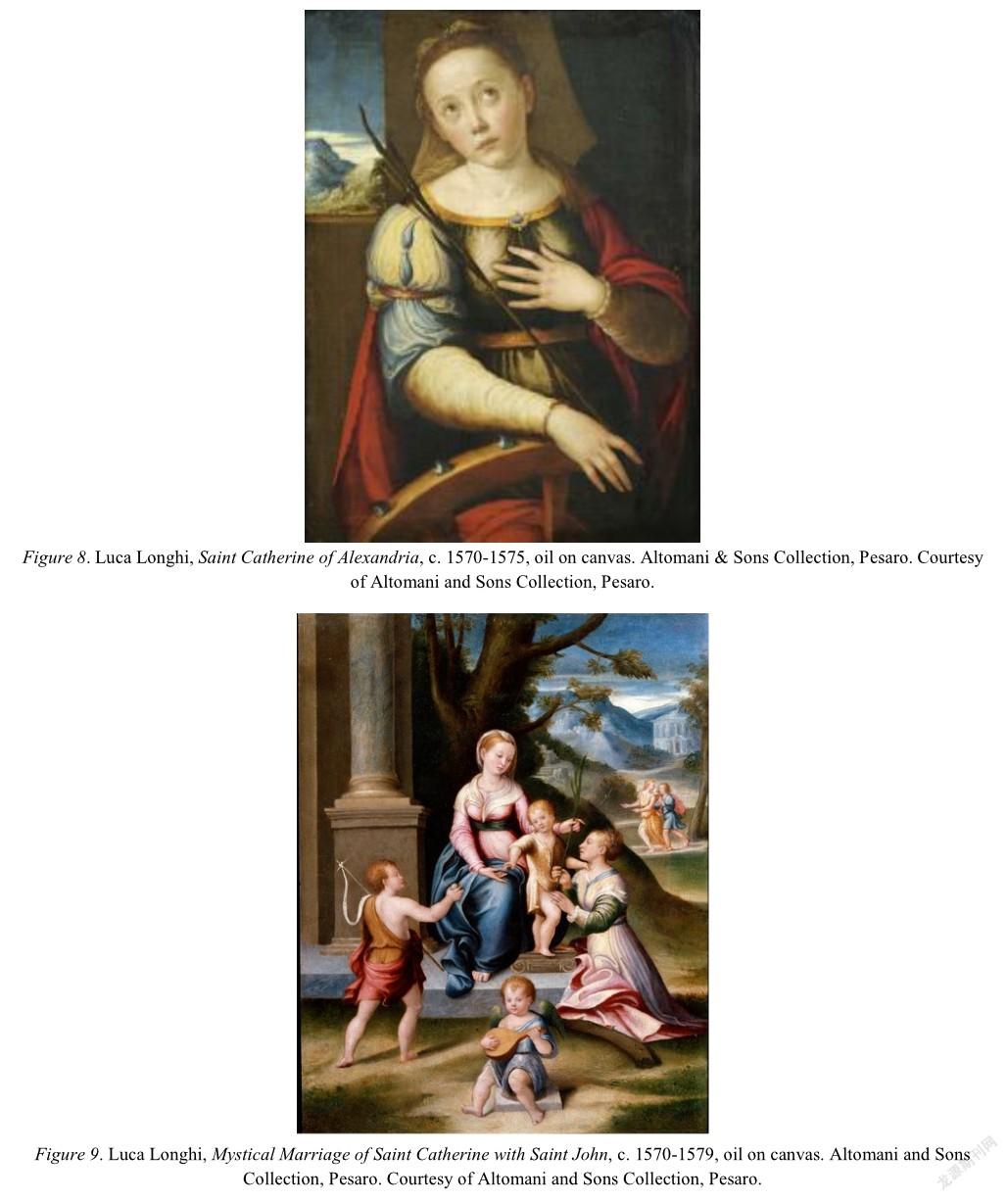

In sixteenth-century Italy, the creation of a self-portrait reveals some obvious features: the image is a reflection from viewing the self in a mirror. Both eyes are scrutinizing the image reflected in the mirror in order to reproduce it on a painted surface. This action is cleverly shown in Francesco Mazzola Parmigianino’s Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror (Figure 4), Sofonisba Anguissola’s Boston Self-Portrait (Figure 5), Lavinia Fontana’s Self Portrait in her Studio (Figure 6), and Barbara Longhi’s Verona Saint Catherine of Alexandria as a Self-Portrait (Figure 7).

One way of identifying a self-portrait is by noting its title. But while titles such as “Self-Portrait,” “Portrait of the Artist,” and the various translations of the concepts are a good beginning, the acceptance of such titles does not guarantee that a given painting is an authentic self-portrait, since owners, art dealers, sellers, and recorders of inventories, wills, and other documents have often invented titles to promote their own interests. For the self-imaging of the sixteenth century, critical writings of ancient, medieval, and contemporary artists, theoreticians, and travelers assist in the interpretation, noted by the ancient Roman historian Pliny the Elder’s Natural History,6 the female medieval writer Christine de Pizan’s The Book of the City of Ladies,7 and works by the Mannerist artists and writers Giorgio Vasari (Lives of the most excellent painters, sculptors and architects)8 and Karel van Mander (Dutch and Flemish Painters).9

The self-portrait begins as an image of the creative process; the artist’s first love is the self. The image of the painter (naturam imitandam esse—nature imitates herself) recorded in ancient writings may be regarded as an acquisition of classical culture and connoisseurs, an era where only the names of Greek painters are known, such as the painters Zeuxis, Apelles, Marcia, and Timarete (Figure 3). Following Plato’s theory of art as mimesis(mimic or parody), as the imitation of nature, the painter becomes a magician.10 These self-portraits by ancient painters can be seen as artists’ copies of nature, and, therefore, their self-images are imitations and not the original of the self.11

In sixteenth-century Italy, the notion emerged that the self-portrait reflected God’s artistry, as divine intelligence passed into the artistry of Nature and the human mind. The artist’s virtuosity became regarded as artista divino (the divine artist), demonstrating that the artist’s genius was inspired by God, as exemplified by Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo. The idea of identifying art with its sister arts or the principle ut pictura poesis (as is painting, so is poetry) derived from Horace’s Ars Poetica, with painting and poetry considered to be sister arts.12 With the interest in Greek culture, this allegorical parallelism (paragone) was appropriated and assimilated by painters during the Italian Renaissance and in Mannerism.13

When one comparatively analyzes the self-portraits of male artists with the self-portraits of female artists in the sixteenth century, one observes that both female and male artists are concerned with portraying themselves as inventors and creators, that is to say, as artists. Therefore, the concept of persona emerges as the same for both genders and reflects the impact of the revival of classical values on the individual as well as the Neoplatonic philosophy of the Renaissance, which provided a nurturing atmosphere for humanistic awareness of the self.14 However, there are differences between self-portraits by male and female artists, depending upon the presentation of the occupation or interest of the individual.15 Self-portraits of male artists focus on status and specific occupation, while self-portraits of female artists add to this rendering educational and cultural accomplishments (Figures 4-6).16 For example, the female artist is rendered as a mother, musician, poetess, teacher, or a collector (Figure 6).17 The female artist expands her role as natural creator (nurturer) into that of artistic creator by observing herself as an object of beauty and admiration (Figures 5-6).18 These self-images provide the viewer with another level of aesthetic awareness, beauty, and artistic excellence through the manifestation of the self. Barbara Longhi’s self-imaging was no exception, as evidenced in her self-portrait as Verona Saint Catherine of Alexandria (Figure 7).19

Saint Catherine of Alexandria, a Self-Portrait of Artistic Virtue

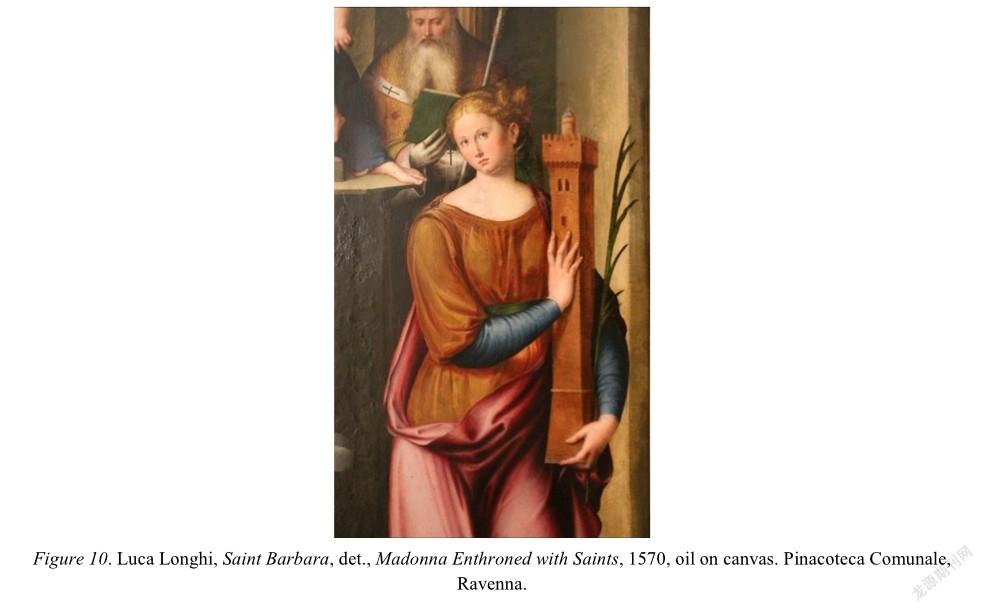

The theme of Saint Catherine of Alexandria was depicted many times by the Longhi family: father Luca Longhi (1507-1580), brother Francesco Longhi (1544-1618), and Barbara Longhi herself. These painters composed two versions: a single—solo—image and a group imagery, or theme of the holy conversation (sacra conversazione) (Figures 8-9).20 Barbara Longhi preferred to depict the solo composition, noted by her several painted versions, although she occasionally also painted Saint Catherine in the theme of Mystical Marriage of Saint Catherine.21

Although challenging and tempting, it is not the purpose of this short essay to discuss all versions, variances, and attributions of the Longhi family’s portrayals on this subject. The ability to recognize the identification of an original creator of an image and subsequent appropriation of said image developed out a painter’s family atelier,in particular in the sixteenth century, will always be a subject of contestation for art historians. The polemic persists about which artist first depicted Saint Catherine of Alexandria with the physiognomy of Barbara Longhi, the painter, and the literature is extensive, persuasive, and plausible when one considers the various arguments.22 In addition, these versions painted by the Longhi family are similar in composition, treatment of color, spatial design, and figure type. Usually, a half-length figure, seated, is depicted gazing at the viewer, with similar attire and veil. The gestures of the hands are associated with the saint’s attributes of martyrdom: hands resting on a broken spiked wheel and holding a palm frond (compare Figures 8 and 7).

Barbara’s father, Luca Longhi, painted the altarpiece Madonna Enthroned with Saints (Benedictine, Paul, Apollinare, and Barbara) between 1562 and 1570 for the Church of Saint Barbara (Figure 10). The painting is signed as “Luca de Longhis Ravennas Pingebat.”23 With care, Luca employed the figure and physiognomy of his daughter as model and her name as an attribute for a symbol of the saint, a three-window tower for her incarceration, and a palm for Saint Barbara’s martyrdom.24

Unlike her father, Barbara Longhi never depicted herself as her patron saint, Saint Barbara. She did, however, compose several paintings with her self-image as a solo figure and as Saint Catherine of Alexandria, including her Verona Santa Caterina di Alessandria of 1590 (Figure 7); and two Saint Catherine of Alexandria, Self-Portraits of 1589, both in the Pinacoteca Comunale in Ravenna.25 Questionably one of the latter two versions has been attributed to her father.26 There is also a claim by some art historians that the one painted by Barbara Longhi is not a self-portrait.27 Other versions painted by Barbara Longhi are the Romania Saint Catherine of Alexandria of 1595 now at the National Museum of Art of Romania in Bucharest, which is a replica of that at the Pinacoteca Nazionale of Bologna, and another very similar painting of 1595 now in the Collection of Altomani and Sons in Pesaro (Figure 13).

Ingeniously, in depicting herself as Saint Catherine of Alexandria, Barbara Longhi decided to impersonate the image of a saint to validate her self-imaging while still retaining moral concordance with the religious views of the Counter-Reformation in the regional area.28 Saint Catherine was a doctor of the Church who philosophically defended her virtue and was a devotee of Christ, for which she was killed;29 this action held great appeal for the faithful of the Counter-Reformation. In the Roman Breviary, revised after the Council of Trent and published in 1568, Saint Catherine of Alexandria and Saint Agnes were retained and remembered in the liturgy as historically reliable saints, while other saints such as Saint Barbara, Saint Cecilia, and Saint Ursula were rarely mentioned.30

Furthermore, Gabriele Paleotti (1522-1597), a Doctor of Civil and Canon Law and Italian Archbishop of Bologna, was a great contributor to the Christian reformations of the Church during the Council of Trent. In 1582, he wrote in his Discourse on Sacred and Profane Images on the merits of painting for a Christian individual, among which are to not only create art that imitates the natural world but also art that imitates for the glory of God([l’individuo] Cristiano aquista insieme un’altra nobile forma … oltre l’assomigliare nella pittura … ad fine maggiore, mirando la eterna gloria).31 He commented on the painter depicting portraits of holy figures employing the self, noting that “the likeness should be of a good and intelligent person revealing the nature of devotion” (l’effigie propia … buona et intelligente … porta probabile apparenza).32 But he also cautioned the artist not to compose a saint’s portrait using the self that might depict an effigy of a commoner or frivolous person(persona mondana) well known by others (“dagli altri conusciute”) because it would be considered a shameful action (cosa indignissima).33

Perhaps Barbara and her family, residing in Ravenna, far away from Trent but close to Bologna, were aware of this mandate. With the depiction of the self as the honorific female saint, Barbara Longhi was responding to aims of the Council of Trent’s decrees and Archbishop Paleotti’s position of creating art for the glory of God, and self-imaging as a saint followed this prescript of a moral and mindful individual, like herself, a devoted daughter and a faithful Christian. This type of self-imagery assisted the devotee, in this instance Barbara Longhi, the painter, to visually impersonate a favorite female saint and emulate the martyrdom experience of said saint. The Council decree urged “religious leaders to diligently teach the Bible along with meaning of the stories and mysteries of redemption in order to be portrayed in paintings and other representations. The depiction of all holy images with their visualization should provide recollections (memoria) and spiritual arousal (exitatio).”34 These experiences (exitatio) would then move viewers “to adore and love God and cultivate piety.”35

It is unclear why Barbara preferred to depict herself as the protagonist Saint Catherine when her patron saint was Saint Barbara, since little is known of the events of her life. It is difficult to even speculate, but one may ponder. Saint Catherine was a historical and honorific personage and highly regarded in the liturgy, hence a more significant saint, compared to the beautiful Saint Barbara, who was tortured by her father, Dioscorus, in the third century CE.36 This brutal filial association may not have inspired the artist, Barbara Longhi, to self-imaging, since she had a benevolent father and teacher (Luca Longhi), and their professional relationship was not just as a model or muse; she was also an administrative assistant in his studio.37 Hence, selecting Saint Catherine connected Barbara with a virtuous female, whose name signifies pure of heart in Greek (kataros), which was appealing to the devoted daughter, faithful Christian, and virgo (a Latin word for unwedded or maiden) Barbara.

The life and legend of Saint Catherine of Alexandria is recounted in Jacobus de Voragine’s Golden Legend.38 The name Catherine, like the name of Agnes, has two significations: within Greek etymology it alludes to suffering and torture and also to purity. Catherine was a learned and noble woman, with abilities in the arts, sciences, and, in particular, philosophy, who protested the persecution of Christians under the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maxentius (283-312 CE). Hence she was tortured by her body being placed on a spiked wheel. Miraculously, the wheel broke—thus the broken wheel with a spike as her attribute—but after this ordeal she was decapitated.

One of the most influential sources for these depictions of the saint was Raphael’s Catherine of Alexandria of 1507, now at the National Gallery in London, a depiction of the saint in ecstasy, leaning on a spiked wheel(Figure 11). She raises one hand to her heart with humility for the divine acceptance of her martyrdom.

In her lifetime, Barbara Longhi was praised for her artistic abilities as a colorist, designer, and portraitist. In 1568, the artist and author Giorgio Vasari wrote, “Unique for their [paintings] purity of line and soft brilliance of color,”39 and in 1575, the academician and theoretician Muzio Manfredi stated: “Her art is quite marvelous, and even her father is surprised by her art, especially her portraits.”40 The two painted versions of Saint Catherine of Alexandria reveal these praises (Figures 7 and 12).

Although Barbara Longhi painted several versions of Saint Catherine of Alexandria using herself as a model,41 in this essay, the focus is solely on two solo paintings of hers: the Verona Saint Catherine of Alexandria as a Self-Portrait of c.1590, oil on canvas, now at the Museo Canonicale of the Fondazione Biblioteca Capitolare, in Verona (Figure 7);42 and the Pesaro Saint Catherine of Alexandria of c.1580–1582, oil on canvas, now in the collection of Altomani and Sons in Pesaro (Figure 12).43 Because of her many depictions of Saint Catherine, I am adding to their title their present location. These portraits of bust length in size demonstrate the artist’s ability to handle brilliant colors, compressed spaces, unique human expression, intimate religiosity, and her ability to establish a personal connection with the viewer.

In the Pesaro Saint Catherine of Alexandria (Figure 12), Barbara Longhi painted a most inventive composition: an almost frontal, bust-length portrait depicting the saint elegantly attired in a golden brocade mantle with myrtle leaves, a plant symbolizing the martyr’s faith.44 The neckline of her dress is decorated with jewels, with corals and pearls, symbols respectively of protection against the “evil eye” and “tears of joy”45 similar to the crown that she wears as a symbol of royalty and immortality.46 Saint Catherine rests her right hand on a spiked wheel while her other hand holds a palm frond, both attributes of her Christian martyrdom. Inventively, on the broken wheel, Barbara placed one hand next to a spike, where she has signed with the initials“B.L.P.” (Barbara Longhi Pinxit), indicating that she is the object and subject in the painting. The saint turns her head toward Heaven and away from the viewer, her beautiful attire, light effects, gestures, and, in particular, her gaze with watery eyes, expressing joy and love, invite the viewer to observe and contemplate. Barbara Longhi emphasized the joyous action of Saint Catherine, who with a gentle smile turns her head and watery eyes upward in ecstasy in order to receive approval for her martyrdom by God and recognition as a saint by the “communion of saints” (Apostles’ Creed) in the celestial court.

In comparing Barbara Longhi’s Pesaro version to her father’s version of Saint Catherine of Alexandria of c. 1570-1575 (compare Figures 8 and 12), some notable observations can be made. In the solo version, Luca Longhi’s saint is portrayed in an interior room with an open window on her left that reveals a landscape with mountains; the blue sky and the golden light suggest a sunset. In the chamber, the saint is placed frontally, resting her arm on spiked broken wheel, one hand holding a palm frond, as depicted in Raphael’s Saint Catherine(compare Figures 8 and 11). The other hand is placed on her chest in an act of offering. Elegantly dressed and veiled, the saint—with Barbara Longhi’s features—turns her eyes toward Heaven for blessings, recognition, and salvation. The red mantle envelops her body, the color alluding to her martyrdom, while her noble status is conveyed by an elaborate belt, a blue and gold color brooch on the edge of her dress, and a matching one on her veil.

Barbara Longhi’s Verona version is not only a portrait of the saint but also a self-portrait of herself. A donation from Canon Stefano Trentossi in 1673 of the Sacristy of the Canonici of the Cathedral, it was restored in 2006 by Alessandra Zambaldo of Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio of Verona, Vicenza, Belluno e Ancona-Regione del Veneto (Figure 7).47 This Verona version is notably different from the Pesaro painting. Here Barbara employed a mirror to carefully portray herself, gazing frontally at the mirror as if she was facing the viewer, thus contrasting with the other pictures, where the figure of the saint looks away from the viewer(compare Figures 7 and 12). In the Verona painting, the artist fused artistic beauty with religious fervor.48 The portrayed saint (the self) looks intensely, capturing the viewer’s visual attention. This protagonist is also scrutinizing herself in a mirror. This transparent artifice, the mirror, is not seen by the viewer but is indicated by the sitter’s direct eye gaze, signaling the importance of the image to the viewer. The intensity of this gaze and the direction of the eyes reveal that the painted image is a self-portrait. In this instance, the painter has portrayed herself as a holy figure emulating the spiritual virtue of Saint Catherine. In this Verona painting, the figure of Saint Catherine presents a broken spiked wheel to the viewer with one hand that also holds a palm frond—a symbol of martyrdom and an attribute of the sainthood, respectively. The palm separates the two aspects of Catherine’s persona: in the natural realm, her royalty as a princess and learned scholar is visualized with her golden crown; and in the spiritual realm, her martyrdom is pictured with her hand resting on the object of her affliction, the spiked wheel.

In the Verona version, Saint Catherine gently points with her index finger at the edge of the wheel where, perhaps once, there were legible initials of her name “B.L.P.” like in the Pesaro version but now lost. The broken wheel, seen in both versions, reminds the devotee about her martyrdom and sacrifice for her Christian beliefs. Although in both versions Saint Catherine is crowned, in the Pesaro painting, the jeweled crown—symbol of glory and immortality—ornaments her long stresses. Traditionally, unbound hair alludes to a single woman, a maiden, or a virgo,49 the female status of Saint Catherine. In the Verona version, the figure is also honored with a royal crown placed on her veiled head, covering her long blond stresses. This golden crown lacks encrusted jewels, but its yellow color alludes to solar divine powers, and the circular shape of the crown implies external and internal cosmic forces.50 Three meanings are apparent: physically, it recalls the saint’s noble birth; intellectually, it honors her studies in philosophy, languages, natural sciences, and medicine; and spiritually, it celebrates her moral standards. Barbara Longhi bathed the attire with brilliant colors of gold, pink mauve, and creamy white. To emphasize the source of martyrdom for the saint, the artist painted the arm that supports the broken spiked wheel with a large sleeve whose golden cloth wraps around a white one. The cap sleeve over the shoulder is designed in the shape of a reversed heraldic crown: a design of small pearls on loops joins the arm sleeve to the shoulder, forming the base of the round crown. Following the contour of the shoulder, golden curved straps of cloth decorate underneath the white cloth that shapes the sleeve, forming the round shape of the crown. Thus there are two crowns: a physical crown placed on the saint’s head; and a decorative crown placed on her attire, both signifying royalty and spiritual glory. In addition, a luminous nimbus surrounds her head as a symbol of immortality and an emanation of wisdom as well as identifying her as a sanctified person.

Conclusion

The Verona Saint Catherine of Alexandria, as a self-portrait, stands out from the portraits of Saint Catherine painted by her father and from her own Pesaro version. In the Verona Saint Catherine of Alexandria, Barbara Longhi’s coloration and the manner in which the attire adorns the figure reveal her strong affinity with the style of Italian Mannerism while the Christian symbolism adheres to the spirituality of the Tridentine Reform. As a faithful Christian, Barbara was aware that human beings are created in the image of God, and she was familiar with the “communion of saints” predicated in the Apostles’ Creed and reinforced as the Tridentine Creed postulated by Pope Pius IV (Giovanni Angelo de’ Medici, 1499-1565) in 1563, Article 7. In this painting, she fused her artistic ability with her devotion. Her desire to identify with and impersonate a particular saint provided her with a self-imaging of righteousness and spirituality. These conceits are revealed in her depiction of Saint Catherine, where the painter focused on the miraculous event in the life of the saints and not on the brutality of death. The celestial nimbus, the carrying of a palm frond, and the resting of her hand on the spike without bleeding—all of these motifs suggest a mystical event. Visually, an image created to spiritual provide a contemplative suspended moment for a devotee as well as for the Christian painter, Barbara Longhi, who envisioned this saint’s imagery.

References

Ackroyd, P. R. (Ed.). (1975). The Cambridge history of the Bible (Vols. 3). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Alzard, J. (1968). The florentine portrait. New York: Schocken Books.

Barocchi, P. (Ed.). (1971-77). Scritti d’arte del Cinquecento (Vols. 9). Milan/Naples: R. Ricciardi.

Biedermann, H. (1994). Dictionary of symbols: Cultural icons and the meanings behind them. New York: Meridian Books.

Blakeney, E. H. (Ed., & Trans.). (1970). Horace on the art of poetry. New York: Freeport.

Bosch, L. M. F. (2020). Mannerism, spirituality, and cognition: The art of enargeia. London: Routledge.

Brown, J. (1986). Woman’s place was in the home: Women’s work in renaissance tuscany. In M. Ferguson, et al., Rewriting the renaissance: The discourses of sexual difference in early modern renaissance (pp. 64-100.). New York: Pantheon Books.

Brown, J. C., & Davis, R. C. (1998). Gender and society in renaissance Italy. London: Routledge.

Brown-Grant, R. (Trans.). (1999). Christine de Pizan, The book of the city of ladies. New York: Penguin Books.

Castiglione, B. (1528). Il cortegiano. Venice: Aldus Manutius.

Catherina King, C. (1995). Looking a sight: Sixteenth-century portraits of woman artists. Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, 59(3), 381-407.

Caxton, W. (Trans.). (1900). Jacopo de Voragine’s the golden legend or lives of the Saints. London: J. M. Dent.

Ceroni, N. (2007). Barbara Longhi, in Italian women artists from renaissance to Baroque. Milan: Skira.

Cheney, L. D. (1988). Barbara Longhi of Ravenna. Woman’s Art Journal (Spring), 16-21.

Cheney, L. D. (1994-2000). “Barbara Longhi,” biographical entry. In D. Gaze (Ed.), Dictionary of women artists. London: Fitzroy Dearborn.

Cheney, L, D., Faxon, A., Russo, K. (2000-2009). Self-portraits by women painters. London: Scholar Press/Ashgate, 2000, repr. & rev. Washington, DC: New Academia.

Chevalier, J., & Gheerbrant, A. (1994). A dictionary of symbols (J. Buchanan-Brown, Trans.). London: Blackwell.

Christine, E. J. (Trans.). (1982). Christine de Pizan, the book of the city of ladies. New York: Persea Books.

Cobb-Stevens, V. (1992). Speech, gesture, and women’s hair in the Gospel of Luke and first corinthians. In L. Cheney (Ed.), The symbolism of vanitas in the arts, literature, and music: Comparative and historical studies (pp. 311-40). Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press.

Cropper, E. (1976). On beautiful women: Parmigianino, petrarchismo and the vernacular style. The Art Bulletin, 58, 374-394.

Cropper, E. (1986). The beauty of woman: Problems in the rhetoric of renaissance portraiture. In M. Ferguson, et al., Rewriting the renaissance: The discourses of sexual difference in early modern Europe (pp. 175-190). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Daniele, G. (2013). Luca Longhi inedito: Una Madonna con il Bambino, Sant’Anna e San Giovannino ed altre dipinti. Romagna arte e storia, 98(April-June), 63-74.

De Garcia, E. G. (1999). Saint Barbara: The truth, tales, tidbits, and trivia of Santa Barbara’s patron saint. Santa Barbara, CA: Kieran Pub. Co.

De Pizan, C. (1999). The book of the city of ladies (R. Brown-Grant, Trans.). New York: Penguin Books.

De Vere, G. (Trans.). (1979). Giorgio Vasari, lives of the most eminent painters, sculptors and Architects (Vols. 3). New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

De Voragine, J. (1260-1900). Golden legend (W. Caxton, Trans.). London: J. M. Dent.

Di Pippo, G. (2020). Saint Catherine of alexandria in the counter-reformation. New liturgical moments. https://www.newliturgicalmovement.org/2020/11/st-catherine-of-alexandria-in-counter.html

Eisenbichler, K., & Murray, J. (Trans.). (1992). Agnolo Firenzuola’s on the beauty of women, 1548. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Ferguson, M. W., Quilligan, M., & Vickers, N. J. (Eds.). (1986). Rewriting the renaissance: The discourses of sexual difference in early modern Europe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Firenzuola, A. (1992). On the beauty of women, 1548 (K. Eisenbichler and J. Murray, Trans. & Ed.). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Frazer, J. G. (1922). The golden bough. New York: MacMillan.

Ghirardi, A. (1994a). Ritratto e scena di genre. Arte, scienza, collezionismo nell’autunno del Rinascimento. In V. Fortunati (Ed.), La pittura Emilia e in Romagna. Il Cinquecento. Un’avventura artistica tra natura e idea (pp. 148-183). Bologna: Nuova Alfa.

Ghirardi, A. (1994b). Lavinia Fontana allo specchio. Pittrici e autoritratto nel secondo Cinquecento. In V. Fortunati (Ed.), Exh.cat. Museo Civico Archeologico (pp. 37-51). Bologna. Milan: Electa.

Guzzo, E. M. (2004). Restauri e donazioni: le ragioni di una mostra”. In E. M. Guzzo (Ed.), Museo Canonicale: Restauri, acquisizioni, studi, catalogo della mostra (pp. 7-12). Verona: La Grafina.

Hall, J. (2014). The self-portrait. London: Thames and Hudson.

Jex-Blake, K. (Trans.). (1896/2019). The elder pliny’s chapter on the history of art. London: MacMillan. repr. Indianapolis, IN: Alpha Edition.

King, C. (1995). Looking a sight: Sixteenth-century portraits of woman artists. Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, 59(3), 381-407.

Kinneir, J. (1980). The artist by himself: Self-portrait drawings from youth to old age. London: Granada Publishing.

Kris, E., & Kurz, O. (1979). Legend, myth, and magic in the image of the artist. London: Yale University Press.

Land, N. E. (1994). The viewer as poet: The renaissance response to art. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

MacLean, I. (1980). The renaissance notion of woman: A study in the fortunes of scholasticism and medical science in European intellectual life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Manfredi, M. (1575). Lettione da lui pubblicamente recitata nella illustre Accademia de Confusi in Bologna. Bologna: Alessandro Benacci.

Mazzi, A. (1914). La galleria di quadri del canonico Stefano Trentossi. Madonna Verona: Bollettino del Museo Civico di Verona, viii, 69-77.

McCuaig. W. (Trans.). (2012). Gabriele Paleotti. Discourse on sacred and profane images. Los Angeles: Getty Publications.

Mendelsohn, L. (1982). Paragoni: Benedetto Varchi’s ‘Due Lezzioni’ and cinquecento art theory. Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press.

Mendelsohn, L. (1982). Paragoni: Benedetto Varchi’s “Due Lezzioni” and Cinquecento art theory. Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press.

Metford, J. C. J. (1983). Dictionary of christian lore and legend. London: Thames and Hudson.

Milanesi, G. (Ed., & Trans.). (1881). Giorgio Vasari. Le vite dei più eccellenti pittori, scultori et architettori (Vols. 9). Florence: Le Monnier.

O’Malley, J. (2002). Trent and all that: Renaming Catholicism in the early modern era. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

O’Malley, J. (2012). Trent, sacred images, and Catholics’ senses of the sensuous. In M. Hall (Ed.), The sensuous in the counter-reformation church (pp. 28-48). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Paleotti, G. (2012). Discourse on sacred and profane images (W. McCuaig, Trans.). Los Angeles: Getty Publications.

Pope-Hennessy, J. (1966). Humanism and the portrait. In J. Pope-Hennessy (Ed.), The portrait in the renaissance. New York: Pantheon Books.

Réau, L. (2000). Iconografía del arte cristiano: iconografía de los santos (Vols. 3) (D. Alcoba, Trans., & J. Sureda and Y. Pons, Eds.). Barcelona: del Serbal.

Rogers, M. (1988). The decorum of women’s beauty: Trissino, Firenzuola, Luigini and the representation of women in sixteenth-century painting. Renaissance Studies, 2, 47-87.

Schroeder, J. J. (Ed., & Trans.). (1978). Canons and decrees of the Council of Trent. Rockford, IL: Tan Books.

Shakespeare, W. (1609). Hamlet. Prince of Denmark, III.ii.19-20.

Simone, S. (2000). Barbara Longhi. In C. Bassi Angelini (Ed.), Donne nella storia nel territorio di Ravenna, Faenza e Lugo dal medioevo al XX secolo (pp. 209-214). Ravenna: Longo.

Simoni, S. (2001). La Madonna in Trono con il Bambino Fra I Santi Benedetto, Paolo, Apollinare e Barbara. Romagna Arte e Storia, 62, 93-99.

Simoni, S. (Ed.). (2013). Spigolando ad arte: Richerche di storia dell’arte nel territorio ravennate. Ravenna: Fernandel.

Simons, P. (1988). Women in frames: The gaze, the eye, the profile in renaissance portraiture. History Workshop Journal, 14-29.

Sleptzoff, L. M. (1978). Men or supermen. The Italian portrait in the fifteenth century (pp. 126-139). Jerusalem: Hebrew University.

Tinagli, P. (1997). Women in Italian renaissance art: Gender, representation, identity. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

van de Wall, C. (Trans.). (1969). Karel van Mander’s Het Schilder-Boeck. New York: Arno Press.

Vasari, G. (Trans. & ed.). (1568). Le vite dei più eccellenti pittori, scultori et architettori. Florence: Giunti.

Viroli, G. (2000). I Longhi: Luca, Francesco, Barbara: Pittori Ravennati, sec XVI–XVII. Ravenna: Longo.

Walsh, C. (2007). The cult of St Katherine of Alexandria in early, medieval Europe. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Warner, M. (1982). Paper title. Book title. New York: Persea Books.

Williamson, P. et al. (1997). Images in ivory: Precious objects of the Gothic age. Detroit: Detroit Institute of the Arts.

Woodall, J. (Ed.). (1997). Portraiture: Facing the subject. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Yuejin Wang, E. Y. (1994). Mirror, death, and rhetoric: Reading later Han Chinese bronze artifacts. The Art Bulletin, 76(September), 511-534.

Zama, R. (2002). Un’inedita Santa Caterina siglata Barbara Longhi. Romagna Arte e Storia, 65, 79-84.

Zama, R. (2011). Barbara Longhi, Entry 7. In M. Pulini (Ed.), Le Terre della pittura tra Marche e Romagna (pp. 48-49). Cesena: Litografia Stampare, San Carlo.

1 Liana De Girolami Cheney, “Barbara Longhi of Ravenna,” Woman’s Art Journal (Spring 1988): 16-21; Liana De Girolami Cheney, “Barbara Longhi,” Biographical entry, in Delia Gaze, ed., Dictionary of Women Artists (London: Fitzroy Dearborn, 1994-2000); Liana De Girolami Cheney (author and editor), Alicia Faxon, Kathleen Russo, Self-Portraits by Women Painters(London: Scholar Press/Ashgate, 2000, repr. & rev. Washington, DC: New Academia, 2009), Introduction, xxi–xxvi, and 42-66; Joan Kinneir, The Artist by Himself: Self-Portrait Drawings from Youth to Old Age (London: Granada Publishing, 1980), 15-20; Joanna Woodall, ed., Portraiture: Facing the Subject (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997), 1-23; James Hall, The Self-Portrait (London: Thames and Hudson, 2014), 75-101.

2 William Shakespeare, Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, III.ii., 19-20.

3 James George Frazer, The Golden Bough (New York: MacMillan, 1922), 192.

4 Paul Williamson et al., Images in Ivory: Precious Objects of the Gothic Age (Detroit: Detroit Institute of the Arts, 1997), for ivory mirror illustrations; Cheney, Self-Portraits by Women Painters, 2-3; Hall, The Self-Portrait, 31-49.

5 Eugene Yuejin Wang, “Mirror, Death, and Rhetoric: Reading Later Han Chinese Bronze Artifacts,” The Art Bulletin 76(September 1994), 511-534.

6 Translation from Naturalis historiae, 79 CE by K. Jex-Blake, The Elder Pliny’s Chapter on the History of Art (London: MacMillan, 1896), Book 35.

7 Translation by Earl Jeffrey Richards with a foreword by Marina Warner (New York: Persea Books, 1982).

8 Translation from Vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori et architettori (Florence: Torrentina, 1550; Giunti, 1568, an enlarged edition with woodcuts portraits) as Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, by Gaston Du C. de Vere, 3 vols. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1979).

9 Translation from Het Schilder-Boeck (Haarlem, 1603-1604, first edition; or 1618, second edition), by Constant van de Wall(New York: Arno Press, 1969).

10 Ernest Kris and Otto Kurz, Legend, Myth, and Magic in the Image of the Artist (London: Yale University Press, 1979), 5.

11 Kris and Kurz, Legend, Myth, and Magic in the Image of the Artist, 39.

12 Horace on the Art of Poetry, ed. and trans. Edward Henry Blakeney (New York: Freeport, 1970).

13 Norman E. Land, The Viewer as Poet: The Renaissance Response to Art (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1994); Leatrice Mendelsohn, Paragoni: Benedetto Varchi’s “Due Lezzioni” and Cinquecento Art Theory (Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1982).

14 John Pope-Hennessy, “Humanism and the Portrait,” in Pope-Hennessy, The Portrait in the Renaissance (New York: Pantheon Books, 1966), 64-100; Jean Alzard, The Florentine Portrait (New York: Schocken Books, 1968), 221-227; Hall, The Self-Portrait, 75-101.

15 L. M. Sleptzoff, “Men or Supermen,” in The Italian Portrait in the Fifteenth Century (Jerusalem: Hebrew University, 1978), 126-139; Patricia Simons, “Women in Frames: The Gaze, the Eye, the Profile in Renaissance Portraiture,” History Workshop Journal (1988): 4-29; Margaret W. Ferguson, Maureen Quilligan, and Nancy J. Vickers, eds., Rewriting the Renaissance: The Discourses of Sexual Difference in Early Modern Europe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986); Catherina King,“Looking a Sight: Sixteenth-Century Portraits of Woman Artists,” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 59, no. 3 (1995): 381-407.

16 John Pope-Hennessy, “The Cult of Personality,” in Pope-Hennessy, The Portrait in the Renaissance, 3-100; Cheney, Self-Portraits by Women Painters, 41-66.

17 The bibliography on this subject is vast. The most notable studies include: Ian MacLean, The Renaissance Notion of Woman: A Study in the Fortunes of Scholasticism and Medical Science in European Intellectual Life (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), 92; P. R. Ackroyd, ed., The Cambridge History of the Bible, 3 vols. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975), 3: 79-93, 213-217; Baldassare Castiglione, Il cortegiano (Venice: Aldus Manutius, 1528), Book 3; Judith C. Brown and Robert C. Davis, Gender and Society in Renaissance Italy (London: Routledge, 1998); Paola Tinagli, Women in Italian Renaissance Art: Gender, Representation, Identity (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997); Judith Brown, “Woman’s Place was in the Home: Women’s Work in Renaissance Tuscany,” in Margaret Ferguson et al., Rewriting the Renaissance: The Discourses of Sexual Difference in Early Modern Europe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986), 209.

18 Elizabeth Cropper, “On Beautiful Women: Parmigianino, Petrarchismo and the Vernacular Style,” The Art Bulletin 58 (1976): 374-394; Elizabeth Cropper, “The Beauty of Woman: Problems in the Rhetoric of Renaissance Portraiture,” in Margaret Ferguson et al., Rewriting the Renaissance, 175-190; Mary Rogers, “The Decorum of Women’s Beauty: Trissino, Firenzuola, Luigini and the Representation of Women in Sixteenth-Century Painting,” Renaissance Studies 2 (1988): 47-87; Agnolo Firenzuola, On the Beauty of Women, 1548, trans. and ed. Konrad Eisenbichler and Jacqueline Murray (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992).

19 Cheney, “Barbara Longhi of Ravenna,” 16-21.

20 Raffaella Zama, “Barbara Longhi, Entry 7,” in Massimo Pulini, ed., Le Terre della pittura tra Marche e Romagna (Cesena: Litografia Stampare, San Carlo, 2011), 48-49; Giulia Daniele, “Luca Longhi inedito: Una Madonna con il Bambino, Sant’Anna e San Giovannino ed altre dipinti,” Romagna Arte e Storia 98 (April-June 2013): 63-74, esp. 70, n. 40.

21 Giordano Viroli, I Longhi: Luca, Francesco, Barbara: Pittori Ravennati, sec XVI–XVII. (Ravenna: Longo, 2000), 208, figure on 207; Viroli, I Longhi, 6; another version of Luca’s Mystical Marriage of Saint Catherine with San Nicholas of Bari was auctioned at Sotheby’s New York, 24 January 2008, Lot 34.

22 See Viroli, I Longhi, 92; Nadia Ceroni, La donazione Levi, a brochure printed in Ravenna around 1994, no publisher; Nadia Ceroni, “Barbara Longhi,” in Italian Women Artists from Renaissance to Baroque (Milan: Skira, 2007), Entry; and Serena Simone,“Barbara Longhi,” in C. Bassi Angelini, ed., Donne nella storia nel territorio di Ravenna, Faenza e Lugo dal medioevo al XX secolo (Ravenna: Longo, 2000), 209-214, esp. 212.

23 Viroli, I Longhi, 75; Serena Simoni, “La Madonna in Trono con il Bambino Fra I Santi Benedetto, Paolo, Apollinare e Barbara,” Romagna Arte e Storia 62 (2001): 93-99.

24 Jacopo de Voragine’s Golden Legend, trans. William Caxton as The Golden Legend or Lives of the Saints (London: J.M. Dent, 1900), 93; Louis Réau, Iconografía del arte cristiano: iconografía de los santos, trans. Daniel Alcoba, ed. Joan Sureda Y Pons, 3 vols. (Barcelona: del Serbal, 2000), 2: 273-283.

25 Cheney, “Barbara Longhi of Ravenna,” 16-21.

26 See Viroli, I Longhi, 92; Ceroni, La donazione Levi, np; and Simoni, “Barbara Longhi,” 212.

27 Angela Ghirardi, “Lavinia Fontana allo specchio. Pittrici e autoritratto nel secondo Cinquecento,” in Vera Fortunati, ed., exh.cat., Museo Civico Archeologico, Bologna, 1994 (Milan: Electa, 1994), 37-51; Angela Ghirardi, “Ritratto e scena di genre. Arte, scienza, collezionismo nell’autunno del Rinascimento,” in Vera Fortunati, ed., La pittura Emilia e in Romagna. Il Cinquecento. Un’avventura artistica tra natura e idea (Bologna: Nuova Alfa, 1994), 148-183; Raffaella Zama, “Un’inedita Santa Caterina siglata Barbara Longhi,” Romagna Arte e Storia 65 (2002): 79-84, esp. 81.

28 Lynette M. F. Bosch, Mannerism, Spirituality, and Cognition: The Art of Enargeia (London: Routledge, 2020), 37-51; John O’Malley, Trent and All That: Renaming Catholicism in the Early Modern Era (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002).

29 Caxton, The Golden Legend, Chapter 7, 1-30; Réau, Iconografía del arte cristiano, 2: 273-283; Christine de Pizan, The Book of the City of Ladies, trans. Rosalind Brown-Grant (New York: Penguin Books, 1999), 203; Christine Walsh, The Cult of St. Katherine of Alexandria in Early Medieval Europe (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007).

30 Gregory Di Pippo, “Saint Catherine of Alexandria in the Counter-Reformation,” New Liturgical Moments, 25 November 2020, https://www.newliturgicalmovement.org/2020/11/st-catherine-of-alexandria-in-counter.html (accessed 5 December 2021).

31 Paola Barocchi, ed., Trattati d’Arte del Cinquecento: fra Maniersimo e Contrariforma, 3 vols. (Bari: Laterza 1961), 2: 119-515, esp. 211, quoting Gabriele Paleotti, Discourse on Sacred and Profane Images. For the English translation, see Gabriele Paleotti, Discourse on Sacred and Profane Images, trans. William McCuaig (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2012).

32 Barocchi, ed., Trattati d’Arte del Cinquecento, 2: 352, quoting Gabriele Paleotti, Discourse on Sacred and Profane Images.

33 Barocchi, ed., Trattati d’Arte del Cinquecento, 2: 352, quoting Gabriele Paleotti, Discourse on Sacred and Profane Images; John O’Malley, “Trent, Sacred Images, and Catholics’ Senses of the Sensuous,” in Marcia Hall, ed., The Sensuous in the Counter-Reformation Church (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 28-48.

34 J. J. Schroeder, O.P., ed. and trans., Canons and Decrees of the Council of Trent (Rockford, IL: Tan Books, 1978), 216.

35 Ibid.

36 Voragine, Golden Legend, trans. Caxton, 93; and Erin Graffy de Garcia, Saint Barbara: The Truth, Tales, Tidbits, and Trivia of Santa Barbara’s Patron Saint (Santa Barbara, CA: Kieran Pub. Co., 1999).

37 Viroli, I Longhi, 24. 38 Caxton, The Golden Legend, Chapter 7, 1-30; de Pizan, The Book of the City of Ladies, 203; Walsh, The Cult of St. Katherine of Alexandria in Early Medieval Europe, passim; Réau, Iconografía del arte cristiano, 2: 273-283.

39 Giorgio Vasari, Le vite dei più eccellenti pittori, scultori et architettori (Florence: Giunti, 1568), trans. and ed. Gaetano Milanesi, 9 vols. (Florence: Le Monnier, 1881), 7: 420-421.

40 Muzio Manfredi, Lettione da lui pubblicamente recitata nella illustre Accademia de Confusi in Bologna, 4 Aprile 1575(Bologna: Alessandro Benacci, 1575), 22-23; also quoted in Viroli, I Longhi, 191.

41 Attribution issues and other iconographical discussion about the versions in the Pinacoteca of Art in Ravenna, Classe, Romania, and Bologna were addressed in previous studies and are considered in my forthcoming book on Barbara Longhi (2022), under contract with Lund Humphries. See Viroli, I Longhi, 92.

42 Attilio Mazzi, “La galleria di quadri del canonico Stefano Trentossi,” Madonna Verona: Bollettino del Museo Civico di Verona viii (1914): 69-77; E. M. Guzzo, “Restauri e donazioni: le ragioni di una mostra,” in Guzzo, ed., Museo Canonicale: restauri, acquisizioni, studi, catalogo della mostra (Verona: La Grafina, 2004), 7-12; Simoni, “La Pelagonitissa di Barbara Longhi,” in Serena Simoni, ed., Spigolando ad Arte: richerche di storia dell’arte nel territorio ravennate (Ravenna: Fernandel, 2013), 71-74, esp. 73 and n. 8.

43 Zama, “Un’inedita Santa Caterina siglata Barbara Longhi,” 79-84.

44 J. C. J. Metford, Dictionary of Christian Lore and Legend (London: Thames and Hudson, 1983), 178.

45 Hans Biedermann, Dictionary of Symbols: Cultural Icons and the Meanings Behind Them (New York: Meridian Books, 1994), 76, on the coral, and 260, on the pearl.

46 Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrant, A Dictionary of Symbols, trans. John Buchanan-Brown (London: Blackwell, 1994), 262-263.

47 Mazzi, “La galleria di quadri del canonico Stefano Trentossi,” 69-77; Guzzo, “Restauri e donazioni: le ragioni di una mostra,”7–12; Simoni, “La Pelagonitissa di Barbara Longhi,” 71-74, esp. 73 and n. 8.

48 Rogers, “The Decorum of Women’s Beauty,” 47-87; O’Malley, “Trent, Sacred Images, and Catholics’ Senses of the Sensuous,”28-48.

49 Veda Cobb-Stevens, “Speech, Gesture, and Women’s Hair in the Gospel of Luke and First Corinthians,” in Liana Cheney, ed., The Symbolism of Vanitas in the Arts, Literature, and Music: Comparative and Historical Studies (Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 1992), 311-340, esp. 328.

50 Chevalier and Gheerbrant, A Dictionary of Symbols, 263 and 265.

杂志排行

Journal of Literature and Art Studies的其它文章

- Ethical Problems in MTI Students’Escort Interpreting from the Perspective of Chesterman’s Models on Translation Ethics

- A Corpus-driven Contrastive Study on Reporting Verbs in Research Articles

- A Contrastive Study of Self-Sourced Reporting Sentence Stems in English and Chinese Journal Articles

- Native/Non-native English Speakers’Attitudes:Addressing Learners’Goals and Needs Towards Pronunciation Issues

- Revenge and Sociality

- A Feature Analysis of Oroqen Ethnic Group’s Semiosphere