Hepatitis C virus: A critical approach to who really needs treatment

2022-02-12EliasKouroumalisArgyroVoumvouraki

Elias Kouroumalis, Argyro Voumvouraki

Elias Kouroumalis, Department of Gastroenterology, University of Crete Medical School, Heraklion 71500, Crete, Greece

Argyro Voumvouraki, First Department of Internal Medicine, AHEPA University Hospital, Thessaloniki 54621, Greece

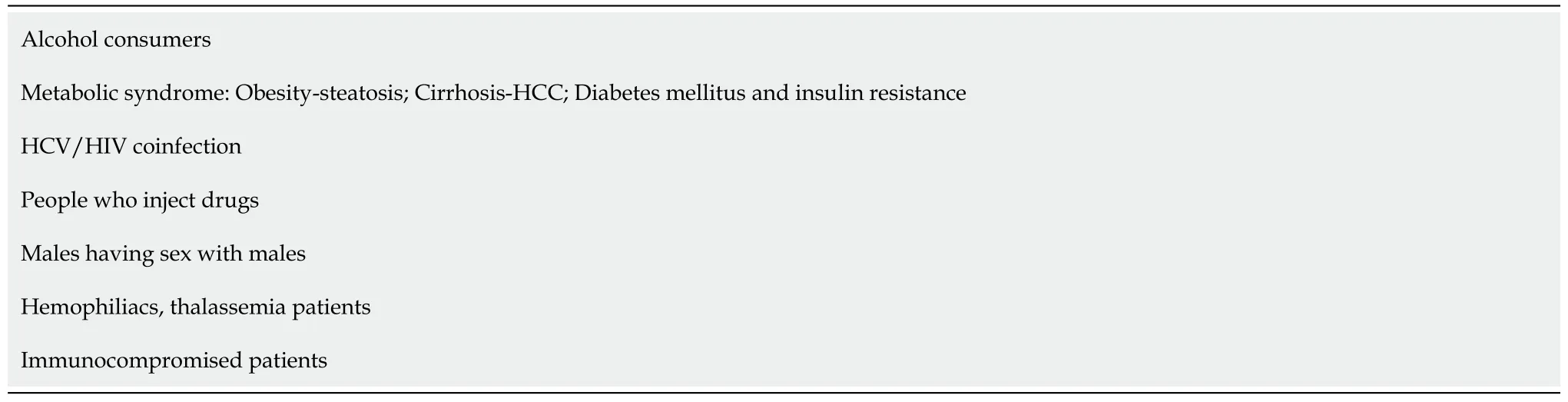

Abstract Introduction of effective drugs in the treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has prompted the World Health Organization to declare a global eradication target by 2030.Propositions have been made to screen the general population and treat all HCV carriers irrespective of the disease status.A year ago the new severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 virus appeared causing a worldwide pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 disease.Huge financial resources were redirected, and the pandemic became the first priority in every country.In this review, we examined the feasibility of the World Health Organization elimination program and the actual natural course of HCV infection.We also identified and analyzed certain comorbidity factors that may aggravate the progress of HCV and some marginalized subpopulations with characteristics favoring HCV dissemination.Alcohol consumption, HIV coinfection and the presence of components of metabolic syndrome including obesity, hyperuricemia and overt diabetes were comorbidities mostly responsible for increased liverrelated morbidity and mortality of HCV.We also examined the significance of special subpopulations like people who inject drugs and males having sex with males.Finally, we proposed a different micro-elimination screening and treatment program that can be implemented in all countries irrespective of income.We suggest that screening and treatment of HCV carriers should be limited only in these particular groups.

Key Words: Hepatitis C, Comorbidities, Screening and treatment policy; Hepatitis C virus; Review

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is genetically variable.Seven genotypes and more than 60 subtypes have been identified so far.Genotype 1 is the most prevalent worldwide[1].A 30% difference among genotypes and a 15% difference among subtypes of the same genotype exist at the nucleotide level.In addition, an enormous diversity within the same infected individual may be present in the form of the so called quasi-species differing by 1%-10% in the nucleotide sequence[2,3].They are categorized on the basis of the hypervariable regions in the envelope protein and the nonstructural 5A protein.These quasi-species are generated through error-prone replication and pose the major obstacle in the development of an effective vaccine.The E2 variability is mainly located in three highly variable regions designated as HVR1 (aa384-409), HVR2 (aa460-485) and igVR (aa570-580)[4,5].

With an estimation of approximately 2 million new infections each year, the real number of individuals harboring HCV may well be underestimated[6].Most new cases go undetected because they are mostly asymptomatic.Underestimation is not limited to low-income countries.In the United States the incidence of new HCV cases has nearly doubled in the past 10 years primarily because of people who inject drugs (PWID).It is suggested that the recorded increase is only a fraction of the true number as the majority probably escapes detection[7,8].

Intravenous drug use is not the main route of transmission in low and middle income countries.In Egypt, PWID was a risk factor only in urban areas, while the main risk factor was hospital care[9,10] and intra-familial transmission of the virus[11].This is also true for Greece[12].Increased incidence of the disease has also been reported in China but without an epidemiological explanation[13].In the European Union one of the additional problems is the increased immigration from countries with a high prevalence of HCV.A crude estimation has shown that approximately one in seven adults infected by HCV in the 31 countries of the European Economic Area is a migrant, and at the same time HCV prevalence is also high in some Eastern European countries.These facts pose a challenge for the budgets of many European Union countries[14].

In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) initiated a campaign to reduce HCV infection rates by 90% by 2030 using the new and highly effective direct acting antivirals (DAAs).The campaign called for an increase of HCV screening and unlimited access to DAA treatment[15].

However, there are inherent limitations to this approach[16,17].Even in the most favorable trials, DAAs do not achieve viral elimination in as many as 2%-10% of cases.Moreover, there is mounting concern that DAAs can select resistant variants that may reduce their effectiveness.Also, DAAs are expensive for most developing countries, while asymptomatic cases pose a worldwide problem as only 20% of infections are diagnosed and of those only 15% are properly treated[18].This is further complicated by the fact that many new cases are found in marginalized populations like PWIDs and males having sex with males (MSM).These groups pose an additional problem as they are prone to reinfection[16].

As a result, only a few countries will be able to eliminate HCV by 2030.Highincome countries will not achieve HCV eradication before 2050 as 80% of them are not on track to meet HCV elimination targets by 2030 and 67% are off target by at least 20 years[19,20].The vast majority of low and middle-income countries are at a very preliminary stage[21-23].Unfortunately, the latter are countries like Pakistan, Egypt, China and India, which have the largest numbers of chronic HCV infections.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has dramatically changed health priorities around the world.It is not surprising that financial resources have been redirected in an effort to fight the new enemy.Therefore, major problems in the different programs of HCV elimination are to be expected even among high-income countries.Disruptions to hepatitis programming have already been reported in Egypt and Italy, two countries with different incomes and COVID-19 problems, and many more are certain to follow[24].Moreover, the odds are against the control of HCV infection without an effective and widely available vaccine[25,26].

Therefore, in the present review, the problems of managing chronic hepatitis C will be analyzed, the populations that are in real need for treatment will be identified and a new, more realistic target of treatment will be proposed that may overcome the difficulties in the global effort to eliminate the disease.

CAN WE ERADICATE HCV BY 2030 WITH DAAS TREATMENT?

The number of new HCV infection rates is increasing worldwide despite the use of the highly effective DAAs.Most of the new infections go undetected as they are asymptomatic.Only 50% of infected people are aware of their infection in the United States[27].DAAs do not protect from reinfection.Therefore, certain marginalized groups like intravenous drug users may be reinfected[17].

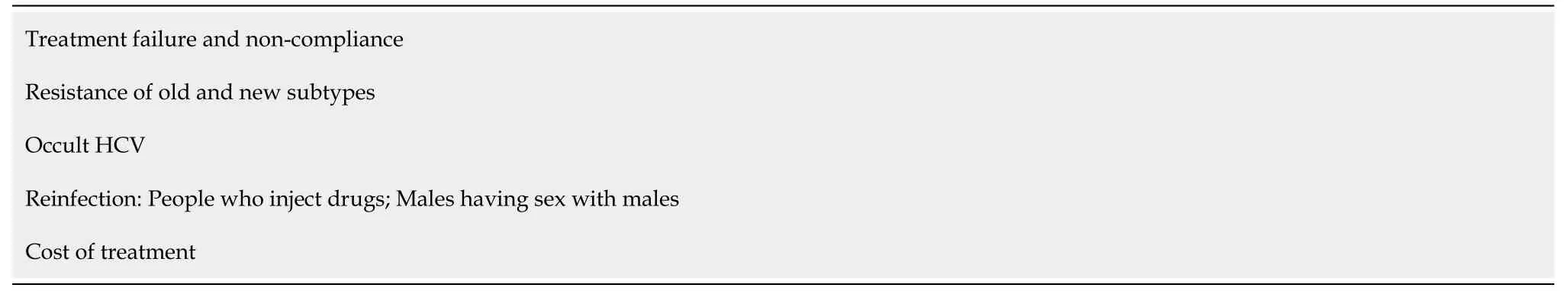

Yet, many investigators are convinced that eradication is possible by treating all HCV carriers, including pediatric patients[28], even in low-income countries provided that cost reduction policies will be adopted[29].An even more optimistic view has been presented.Since 2015, after the wide use of DAAS in Spain, a profound reduction in HCV cirrhosis hospitalization has been reported.The investigators predicted that by 2025, HCV-cirrhosis will have practically disappeared as a cause of hospital admissions[30].However, in most instances conditions are set and reservations are expressed (Table 1).

Table 1 Reasons for failure of the World Health Organization 2030 hepatitis C virus elimination program

A model projection of the impact of DAA treatment on the elimination of HCV infection showed that the WHO target for 2030 could be achieved only after an annual net regression of 7%.Currently the projections made indicate that the annual regression is only 0.4% worldwide, and therefore elimination will be impossible[31].Projection studies of different scenarios[32], such as those including countries with a high prevalence of HCV such as Pakistan[33], have indicated that HCV elimination may be feasible but only after substantial new investments from national budgets even in Europe[34].Conditions that should be fulfilled before elimination can be on target have been described for special populations like HIV + PWID or HIV + MSM.Harm and behavior risk reduction interventions in addition to DAA treatment and a substantial increase of screening, showed improved results[35].

Treatment failure and non-compliance

One hundred percent sustained virologic response (SVR) is not feasible even with the latest DAAs.The best treatment results are reported as 90%-97% in most series.This means that 3%-10% of treated patients do not achieve an SVR and may become resistant to available regimens[36].Response rates may even be lower than 90% in certain groups.Thus, in a recent large meta-analysis reviewing 49 reports, SVR was lower than 90% in 11/49 studies of patients without hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[37].In a real-life cohort of cirrhotic patients, viral clearance was obtained by 88% (175/199) of patients with varying responses among genotypes[38].

Compliance with treatment is another obstacle in the eradication of HCV.This is particularly evident in special groups.In a recent study, compliance was associated with the time of drug dependence.Those with shorter periods of drug dependence had the highest compliance with an inadequate 47% compared with the even worse 38% of longer-time users[39].In France, drug uptake was low in HCV patients with PWID and alcohol use disorders (AUD) despite an improvement after DAA introduction as compared to interferon (IFN)-based treatments[40].

Resistance of old and new subtypes

Quasi-specie is the concept that explains the development of resistance to DAAs[41].Low levels of resistance-associated substitutions < 15% in the NS5A region have no significant effect on treatment outcomes, but proportions greater than 15% at baseline are associated with treatment failures[42].Furthermore, presence of NS5A resistanceassociated substitutions may be responsible for the low 83% SVR reported in the ASTRAL-4 trial in certain genotypes[43].Similarly, in a Chinese study of sofosbuvir (SOF)/velpatasvir (VEL), NS5A resistance was responsible for 89% SVR in noncirrhotic patients with subtype 3b, while only 50% of cirrhotic patients achieved SVR after 12 wk of SOF/velpatasvir[44].

It is clear today that baseline resistance-associated substitutions to DAAs can have a significant effect on the treatment of “older” genotypes preventing SVR in many patients[45].

However, the real problem occurred when newly identified subtypes appeared in many countries.HCV classification now includes a larger number of subtypes, like 1 L, 2r, 3k, 4w, 6xa, 7a and 8a, 6 and probably many more[1].They were extremely rare in countries where research is usually done, but they are relatively common in some low and middle-income countries as well as in immigrants in Europe and North America originating from these countries.Some of those subtypes are inherently resistant to several NS5A inhibitors[46,47].

In line with these findings, a Rwandan study with SOF/ledipasvir (LDV) showed an SVR rate of only 56% in the subtype 4r, much lower than the 93% SVR in patients with other genotype 4 subtypes[48].A very recent report studied infections with unusual subtypes from Africa and South East Asia.The report claims that only pibrentasvir (PIB)was effective against all, and the recommendation given is to use a combination of glecaprevir (GLE) and PIB as first-line treatment for these patients.However, no data that these subtypes were indeed sensitive to GLE were presented[49].

It should be noted that in these countries only generic DAAs with an inherent resistance against these subtypes exist.It will therefore not be long before these resistant subtypes spread across Europe or North America.In an unselected cohort of African immigrants infected with an unusual genotype, including the novel subtype 1p, the SVR was 75%[50].These studies indicate that the need for research on new drugs should not stop because these failures could jeopardize all HCV elimination efforts[51,52].

Occult HCV

Occult HCV infection (OCI) refers to the presence of HCV RNA in hepatocytes or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), without HCV RNA in serum.OCI has been demonstrated in hemodialysis patients, HCV/HIV coinfection and HBV-HCV coinfection but also in 3% of the general population[53].In a recent study, the prevalence of OCI in HIV-infected individuals was 11.4%.Most patients were infected with the subtype 3a followed by the subtypes 1a and 1b[54].OCI is also common in patients with malignant lymphoproliferative disorders.Ultrastructural examination of PBMCs demonstrated intracytoplasmic vacuoles enclosing viral-like particles[55].The prevalence of OCI after treatment with DAAs was found to be considerably high.As a consequence, a dual testing for HCV RNA done in both PBMCs and serum at the end of treatment with DAAs as well as during validation of the SVR was recommended[56], a reasonable suggestion that will however increase the cost.Parts of the HCV 5’-noncoding region genomic RNA sequences were demonstrated at the DNA level in the extrachromosomal circular DNA fraction of PBMCs resulting in OCI[57].

Reinfection

The problem of reinfection may become a real obstacle in the near future.Reinfection mostly occurs in patients with persistent risk factors like PWID.A 10%-15% risk of reinfection after 5 years of SVR has been repeatedly reported[58].China, Russia and the United States have the highest number of PWID with a very high HCV prevalence, and therefore the risk of reinfection is also very high.An additional issue is that reinfection rates have not been studied in low-income countries where both intracommunity transmission and transmission through medical practice are still very common[59].A recent meta-analysis of 36 studies has demonstrated a relapse rate of around 6/100 person years among drug users.There was no difference between IFNbased and DAA treatment, but patients receiving opioid agonist therapy had a lower reinfection rate[60].

Most HCV cases are reinfected with a different strain of the virus after SVR.However, some patients relapse with the same strain they had at the commencement of treatment[61,62].Interestingly enough, reinfection rates seem to be higher after spontaneous clearance of the virus than after successful DAA treatment (at least for the first few years of the reported follow-up)[63].

Relapse or reinfection by a new strain is possibly related either to exhaustion of HCV-specific T cells or to the emergence of escape mutations.In this respect, it is interesting that DAAs do not lead to a reversion of the T cell exhaustion observed in chronic HCV infection[64].

Cost of treatment

An additional serious problem in the HCV elimination project is the cost of treatment.Most studies consider eradication programs cost-effective with almost all of them using Markov mathematical models.

A study from Switzerland claimed that a break-even for the health system will be achieved by 2031 if all fibrotic stages were treated[65].In the United States, treatment of all eligible HCV patients with SOF/LDV would require investing 65 billion dollars over the next 5 years[66].

A more recent study in the United States reported that the pangenotypic SOF treatments (SOF/VEL, SOF/VEL/voxilaprevir) were considerably more cost saving than the equally effective GLE/PIB treatment[67].In a Hong Kong study, elbasvir/ grazoprevir was the least costly DAA treatment, dominating over most other DAAs for genotype 1 patients at a quality-adjusted life-year of 9000-11000 United States dollars[68].

In India, the use of SOF/VEL is proposed over SOF/ledipasvir or SOF/daclatasvir (DCV) to all HCV-infected people but only if there are no budget constraints.If budget is a problem, SOF/VEL is recommended for cirrhotic patients only[69].In a recent study from Japan, GLE/PIB generated higher quality-adjusted life-years and lower lifetime costs compared to all other DAAs[70].

Even in low income-countries like Vietnam, all DAA treatments for patients with genotypes 1 and 6 were cost-effective, but the combination of SOF/VEL was the most cost-effective among them[71].

In contrast, SOF/VEL treatment was not the most cost-effective option for patients with genotype 1b compared with other oral DAA agents in China.Therefore, a price reduction of SOF/VEL would be necessary to make it cost-effective and simplify treatment, achieving thus the goal of HCV elimination[72].

In Italy, a Markov model has shown that treating all HCV patients at an early stage of the disease is cost effective for the Italian Healthcare System[73].

A different approach was adapted in another Italian study that estimated the breakeven point in time.This is the period of time required for the total saved costs to be recovered by the Italian National Health System investment in DAA treatment.The break-even point in time was not achieved for those treated in 2015 due to high DAA prices and severity of disease of treated patients.On the other hand, the estimated break-even point in times were 6.6 years and 6.2 years for those treated in 2016 and 2017, respectively.The total cost savings after 20 years would be €50.13 million and €55.50 million/1000 patients treated in 2016 and 2017, respectively[74].

In the elimination scenario, viremic cases would decrease by 78.8% in 2030 compared to 2015.The direct and indirect costs would range from €3.2-3.4 billion by 2030, but elimination of HCV would be impossible without an extensive screening program.The WHO elimination strategy can possibly be achieved and is cost-saving despite the financial uncertainty of DAA cost in Greece[75].

In Spain, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio for screening of the general population plus treatment was reported to be below the accepted willingness-to-pay thresholds in most studies, and therefore screening plus DAA strategy is considered to be costeffective[76].The same results were reported from Belgium where a policy of broad screening plus DAA treatment was advocated[77].

In Germany by contrast, after a cost analysis, the recommendation was to screen all of the PWID population while applying a less extensive screening in the MSM and general population[78].Screening all South Korean patients twice followed by SOF/LDV treatment was cost-effective as compared to the current high-risk screening, while GLE/PIB was not cost-effective[79].

However, there are many reservations as to the cost-effectiveness of the WHO elimination program[80].The amount required for Pakistan has been estimated at 3 billion United States dollars[33].A price analysis of some of the most commonly used DAAs across 30 countries has shown that DAAs are unaffordable in many countries.Prices at that time were variable and unaffordable, being a threat to the sustainability of many health systems[81].Treatment prices have since fallen and are currently 25000 dollars in the United States.Even so, this cost is prohibitive without medical insurance.Only 37% of patients were treated in the United States for financial reasons[82].Pharmaceutical companies are allowed to sell DAAs at higher prices in highincome countries and at low prices in low-income countries[83].In Pakistan, generic drugs brought the cost of DAAs down to 60 United States dollars per treatment, which is the lowest price in the world[31].

The cost of quality-adjusted life-year gained in 60-year-old patients was approximately 9000 United States dollars at current DAA prices in Japan.HCV treatment would only be cost-effective within the next 5-20 years after a price reduction of 55%-85%[84].

In low-middle income countries of Africa, elimination programs cannot be financially viable without a substantial increase in health funding or a gross decrease in assay prices.Screening strategies would require 8%-25% of the annual health budget in these countries only to diagnose 30% of HCV-infected individuals[83].

However, an alternative low cost approach is usually neglected.A study in Dundee, Bristol and Walsall has demonstrated that needle and syringe programs are effective and low-cost interventions in the highly vulnerable PWID population, at least as far as transmission reduction is concerned[85].

An earlier report has indicated that Markov models have many flaws.Alcohol drinking is a factor that is not acknowledged in many cost analyses.Yet alcohol influences the outcome of HCV infections[86].

A serious event has changed all estimations.The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 pandemic has redirected a substantial amount of national health spending in almost all countries worldwide.Even if recent estimations expect approximately 72000 more liver-related deaths after 1 year of the elimination program delay, the number is small compared to more than 1 million deaths attributed to COVID-19 disease in less than a year[24].

In view of the above, one question still remains.Why are more expensive recommendations proposed when all reported trials indicate > 90% SVR? This is evident if one compares the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) recommendations of 2017, 2018 and 2020.Resistance cannot be the sole answer[87-89].Three SOF-based treatments not only had SVR > 90% but their effects were equally fast in a series of patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis[90].Even low-priced generic DAAs were both clinically effective and cost-effective[91,92].Similar efficacy between SOF/DCV and SOF/VEL in genotypes 2 and 3 was also reported in a real world study[93].In a very recent study on genotype 2, SOF in combination with DCV, LDV or VEL and GLE/PIB had similar high SVR rates, irrespective of cirrhosis or chronic kidney disease[94], and similar results were reported in a real-life recent study of three regimens including SOF/DCV, SOF/VEL and GLE/PIB tested in genotype 3[95].SOF/LDV SVR rate was 97% compared to 100% of SOF/VEL in GT6 after 12 wk of treatment[96,97].In a meta-analysis of 34 studies, SOF/DCV, SOF/VEL, SOF/VEL/ voxilaprevir and GLE/PIB were found to have similar SVRs in both non-cirrhotic (95.24%) and cirrhotic (89.39%) patients[98].Better results for SOF/LDV compared to SOF/VEL were reported in PWID[99,100].

It should be noted however that no real direct comparisons exist in most reported studies as exemplified in an emulated randomized trial where SOF/VEL were equally effective as SOF/LDV in genotype 1 patients[101].

Although cause-specific analysis demonstrated that persons with SVR were less at risk for liver-related mortality than those without SVR or never treated patients, the expected decrease in overall mortality has not yet been observed.These findings may raise hopes for the future, but the final elimination result remains to be proven[102].

No analysis of difficulties in HCV eradication would be complete without mentioning HCV vaccines.It is almost impossible to achieve complete HCV elimination without a vaccine, but the real problem is that we cannot have a vaccine, at least not for the time being.An excellent review on the reasons why HCV cannot be eradicated without an efficient vaccine has been recently published[25].

A model based on 167 countries showed that only between 0 and 48 countries could achieve an 80% HCV incidence reduction without a vaccine.The number went up to 15-113 countries with a 75% effective vaccine and 10-year duration of protection, while billions of United States dollars could be saved across 78 countries at a cost of 50 United States dollars per vaccination[103].

Spontaneous clearance of HCV has been correlated with the development of neutralizing antibodies[104] targeting the E2 envelope protein of the virus[105].An earlier study showed that induction of neutralizing antibodies was feasible in chimpanzees and human volunteers[106].CD4 T cell responses against envelope proteins E1 and E2 were also observed in humans[106,107].For the time being vaccines based on proteins of the E2 hypervariable region are not producing satisfactory results[108].

A different vaccine based on the use of a replication defective adenovirus containing the entire non-structural proteins was also developed[109,110].This vaccine elicited a broad and durable CD4/CD8 T cell response, IFN-g production and memory cell development in humans.The same group developed and tried in a phase 1 human trial a vaccine based on a replication defective simian adenoviral vector and a modified vaccinia Ankara vector containing the NS3, NS4, NS5A and NS5B proteins of the genotype 1b.An effector and T cell memory response were developed[111].

However, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase I and II clinical study mostly on PWIDs who received either the vaccine or placebo did not show a protective effect against the development of viral persistence.The protection provided was no greater than that provided by the placebo[112].Recent investigation on HCV vaccine adjuvants demonstrated that the induction of a strong T and B cell immunity is enhanced by choosing the right adjuvant[113].The subject of vaccines producing neutralizing antibodies has also been briefly reviewed in two recent editorials[114,115].

HCV INFECTION: HOW DANGEROUS IS IT REALLY?

It is estimated that 5%-20% of patients with chronic HCV will develop liver cirrhosis[116,117], while approximately 25% of subjects will clear the virus after the initial infection[118].It is also stated that approximately 27% of liver cirrhosis and 25% of HCC cases are attributable to chronic HCV[119].This estimate is based on studies of patients with advanced liver disease.

Efforts to determine the natural history of HCV are not easy because of the inherent characteristics of the disease.Its onset cannot be verified with certainty and its course may be unusually prolonged.Disease outcome reports were mainly based on retrospective studies concluding that at least 20% of chronic infections develop cirrhosis within 20 years of the disease onset.By contrast, studies that used a retrospective/prospective approach have produced different results at least in certain population groups.Among young people, particularly young women, spontaneous resolution was more common than previously thought, and cirrhosis developed in only 5%of infections or less.The major drawback of most studies is that natural history studies rarely exceed the first 20 years so that evolution beyond this time is usually the result of predictions through models.An additional problem is that many confounding factors that influence outcome are not taken into account[120].

The first paper that raised questions about the real natural course of HCV was reported almost 30 years ago.An accurate infection time was ascertained for over 94% of the 568 patients, as participants were infected by transfusion.More importantly, two control groups (526 first controls and 458 second controls) were also included.After an average of 18 years, life-table analysis showed that all-cause mortality was 51% for those with transfusion-associated non A non B hepatitis compared to 52% and 50% for the control groups.The survival curves for the three groups were almost identical.Liver-related mortality was 3.3%, 1.1% and 2.0%, respectively.(P= 0.033 between hepatitis and the combined control group).Most importantly, 71% of liver-related deaths occurred in patients with chronic alcoholism.There is no specific mention of the causes of non-liver mortality in all groups, but one can assume that controls had more cerebrovascular accidents than the hepatitis group[121].

As a result of this study, one could further assume that if a curative treatment was given leading to a reduction of liver-related deaths in the hepatitis group, then survival would be more than the general population, which is rather odd.However, there may be a plausible explanation after the demonstration of changes in the lipid profile of HCV patients[122,123].HCV-infected patients show significantly lower levels of cholesterol with a reduction of low-density lipoprotein levels compared to healthy controls irrespective of the degree of hepatic fibrosis[124,125].Viral clearance increases levels of low-density lipoprotein and total cholesterol[126].Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that after treatment more cerebrovascular accidents will equate the overall mortality of patients with general population mortality.

Mortality and morbidity data of the same patients and controls after approximately 25 years of follow-up were presented.All-cause mortality was 67% among 222 HCV cases and 65% among 377 controls.Yet again, liver-related mortality was 4.1% and 1.3%, respectively (P= 0.05).Interestingly, among the 129 living persons with transfusion-associated hepatitis, 70% had proven HCV and 30%, non-A-G hepatitis.In addition, 17% of all those originally HCV infected had cirrhosis[127].

There have been more studies verifying the fact that HCV may be a rather benign condition unless a harmful confounding factor like alcohol is added.Thus, many children acquired HCV infection after cardiac surgery before blood donors were screened for HCV in Germany.After about 20 years, the virus had spontaneously cleared in many patients, and the clinical course in those with chronic infection was more benign than expected when compared to infected adults[128].

A very long follow-up of 45 years was reported in a group of military recruits.HCV-positive persons had very low liver-related morbidity and mortality rates suggesting that healthy HCV-positive persons may be at low risk for progressive liver disease[129].

Older patients with tuberculosis sequelae, transfused at a younger age, entered a study approximately 30 years after the infection and were followed up for an average of 5.7 years after entry.Overall, 64% of HCV-infected and 57% of non-infected people had died.The main cause of death was tuberculosis sequelae in 42% and 46% of patients, respectively.Although liver-related deaths during follow-up were higher in HCV-infected patients, the overall mortality was similar between the two groups[130].

Similar findings were reported in a group of transfusion recipients from Denmark.After 22 years of follow-up no difference was found in all-cause mortality between HCV-exposed and non-exposed patients, but liver-related mortality was higher in the HCV group[131].Even in specific high risk groups similar results have been reported.In a cohort of community-acquired HCV among mostly PWIDs, only 8% had overt cirrhosis, while no HCC cases were identified after 25 years of follow-up.Moreover, HCV-infected individuals were 8 times more likely to have committed suicide or die from drug overdose than from liver-related disease[132].

In a cohort of 1667 PWID with HCV infection for a mean of 14 years and followed up for an additional mean of 8.8 years, a low incidence of liver-related mortality of 3/1000 years was found.The risk of end-stage liver disease was higher for persons who ingested more than 260 g of alcohol per week.Two hundred and ten of these patients without advanced liver disease were randomly selected to have a liver biopsy.Only 2 had cirrhosis (1%)[133].

In another PWID cohort, an all-cause high mortality rate of 1.85/100 person-years after 33 years of follow-up was found, but it was not related to persisting HCV infection.Intoxication and suicide were the main causes of death[134].

Using statistical models for untreated HCV-infected PWIDs, the time to cirrhosis was estimated to be 46 years, and estimations for the time required to reach the F3 fibrosis stage was 38 years using stage-specific estimates[135].

Nine hundred and twenty-four patients with a known date of transfusion-acquired HCV were followed up for 16 years after infection in the United Kingdom.They were compared to 475 not infected transfusion recipients.All-cause mortality was not different between cases and controls, but the risk of liver-related mortality was higher among cases.It should be noted that nearly 30% of the HCV-infected cases that died directly from liver disease had also reported excessive alcohol consumption[136].

Almost identical data were reported from a cohort of East German women who were also exposed to HCVviacontaminated Rh immunoglobulin.Clinical cirrhosis was identified in 4 (0.4%) of 917 infected women, 2 of whom died, 1 from HBV coinfection and 1 as a result of heavy alcohol use.Among the 403 chronically infected women in this study who underwent liver biopsy after a mean duration of infection of 20 years, only 3% exhibited bridging fibrosis, and none had cirrhosis[137].

Interestingly, more women of the initial group were later identified and followed up for 25 years.In total, 1980 women representing 70% of the total cohort were reexamined; 46% were positive for HCV RNA.Only 0.5% had overt liver cirrhosis, 1.5% developed pre-cirrhotic stages and only one HCC was diagnosed.Ten died of HCVrelated complications, but in five of those an additional comorbidity was present[138].

Since this was an ideal homogeneous population to investigate the course of HCV infection, 718 patients were further evaluated at 35 years after inoculation.Four groups were compared for liver disease and mortality: self-limited HCV, untreated chronic HCV and treated condition with or without SVR.Overall, 9.3% of patients had clinical signs of cirrhosis.End stage liver disease was higher in the non-SVR group (15.3%), whereas the overall survival was significantly higher after SVR compared to untreated patients or non-SVR.However, looking at the details of the study, it is obvious that the survival probability is significantly decreased only in overweight women and even more so in cases of obesity.The same is true for the development of extensive fibrosis or cirrhosis[139].

A similar study from Ireland included 376 women with anti-D contamination, infected with HCV and followed up for about 17 years.Liver biopsies showed inflammation in 356 of 363 women (98%).The inflammation was mild (41%) or moderate (52%).Only 7 women (2%) had probable or definite cirrhosis, and of those only two reported excessive alcohol consumption[140].

After 5 additional years of follow-up, inflammatory scores were increased in 18% and decreased in 28% of patients.Forty-nine percent of patients had no change in fibrosis, 24% showed regression and only 27% showed progression, while 4 patients (2.1%) developed cirrhosis.Given the age of these women, currently in their fifth decade, some may still be at risk for more advanced liver disease, but for most of these patients it appears unlikely[141].

A third follow-up paper appeared presenting data from 36 years after contamination.In total, 682 patients were studied, including the 374 women chronically infected with HCV.Nineteen percent of them had developed cirrhosis, while all-cause mortality was 13% (4.9% died from liver-related causes) as opposed to 6.8% of the noninfected women.Liver-related, but not all-cause mortality, was significantly higher between the two groups.At face value, the results indicate that cirrhosis and liverrelated deaths had increased during the last 5 years of follow-up.However, when factors associated with cirrhosis were examined, high alcohol intake, diabetes mellitus and obesity were present in the majority of cirrhotic women.It should also be noted that over two-thirds of cirrhotic patients were still alive[142].

Hemophiliacs were a group of patients heavily infected with HCV prior to the introduction of viral inactivation of factor concentrates and blood screening.Only hemophiliacs with HCV/HIV coinfection had a lower survival compared with HCV mono-infected who had a similar mortality with non-infected hemophiliacs over 10 years.There was no survival gain from anti-HCV treatment (IFN) or from achievement of an SVR[143].

One hundred and six HCV RNA positive hemophiliacs were followed up for approximately 30 years, and 34% were HIV coinfected.All-cause mortality was 44% in HIV positive patients and 29% in HIV negative patients.Liver-related mortality was 12.5% and was not different between the two groups.In this cohort as well the probability of cirrhosis was significantly increased when either HBV coinfection or substantial alcohol consumption were present[144].

There have been studies indicating that HCV infection is associated with both a high rate of cirrhosis and/or high mortality.However, these are in disagreement with studies where the contamination time point can be ascertained.Most mortality studies report on cirrhotic patients,i.e.the final stage of HCV infection usually comparing mortality without and with viral elimination.Thus, an Italian study showed that patients with compensated HCV cirrhosis achieving SVR by IFN obtained a significant benefit as they level their survival curve to that of the general population.But the controls were based on the standardized mortality ratio of the age and sex matched general population.Importantly, no mention of drinking or metabolic syndrome was made[145].

Higher mortality rates compared to the general population even after SVR were reported from Denmark.The time point of contamination was not ascertained.Half of the patients were heavy drinkers[146].Similar results were also reported in 1824 patients from Scotland, followed up for an average of 5.2 years after SVR.In total, allcause mortality was 1.9 times more frequent for SVR patients than the general population.Characteristics associated with increased mortality were markers either of heavy alcohol consumption or intravenous drug use.Without these behavioral markers an equivalent survival to the general population was noted[147].

A reduction in serious liver-related events was also noted in a prospective study of patients with HCV-compensated cirrhosis who achieved an SVR.SVR reduced overall mortality and risk of liver-related deaths.However, metabolic features were associated with a higher risk of HCC in patients with SVR.No alcohol consumption was reported[148].

In a study from Japan, the presence of HCV viremia increased mortality, mainly due to liver-related deaths.There were no biopsies at the beginning of the study, and the cause of death was based on death certificates[149].

Paid blood or plasma donors were studied after a median of 27 years from the last blood donation to the time of survey.HCV RNA was detected in 592 individuals.A high 27.2% of them were considered to have cirrhosis by liver stiffness measurement.Almost 50% of the total were overweight.No intravenous drug use was mentioned, and insulin resistance (IR) was significantly higher in HCV-infected blood donors compared to the non-infected ones.More importantly, the time point of infection was not known[150].

In another study of paid plasma donors with HCV infection from China, liver cirrhosis or HCC developed in 10.00% of individuals, with a liver-related mortality of 8.18% after 12-19 years of follow-up.Alcohol was again a risk factor involved in the outcome of HCV infection[151].

In a recent study, age-sex standardized mortality ratios for patients with an HCV infection were calculated and compared to the general population.All-cause age-sex standardized mortality ratio were 2.3 times higher.No confounding factors like alcohol, obesity or HIV coinfection were reported in detail[152].

The significance of confounding factors is clearly exemplified in a recent study by the same group where the median age of death was lower in persons with evidence of HCV than the general population (53 yearsvs81 years).A significant proportion of persons with HCV died of external causes, liver disease and HIV compared to the general population[153].

A recent investigation reported on the natural history of HCV in children and young adults after a median follow-up of 33 years.The modes of transmission were intravenous drug use (53%), blood product exposure (24%) and perinatal infection (11%); 55% of them were treated with IFN and the rest with DAAs.SVR was obtained in 75%.Mortality rate was higher in patients without SVRvsthose with SVR, but SVR did not abolish mortality altogether.Almost 40% of patients consumed alcohol heavily or were HIV coinfected.No mention of the presence of metabolic syndrome was reported[154].

Mortality is not high even in patients with advanced/decompensated HCV cirrhosis with Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) > 10.In a recent long-term follow-up after initiation of treatment with DAAs, a meaningful decrease of 3 or more in MELD occurred in 29% of patients, while a final MELD score of < 10 was obtained in 25%.Only 11% died after a median follow-up of 4 years.In view of the marginal changes that were achieved, the authors concluded that the low mortality was certainly not due to the favoring effect of DAAs[155].

HCV cirrhotic patients survived longer than those with alcoholic cirrhosis, while HBV patients were over twice at risk of dying compared with HCV patients.Patients with alcoholic cirrhosis had a higher risk of decompensation compared to those with HCV, while patients with HCV plus alcohol use had a significantly higher rate of decompensation compared with HCV alone.The highest median decompensation-free time was noted in the HCV patient group[156].

A large recent meta-analysis updated prognostic estimations of important patient subpopulations.Findings indicate that HCV’s natural course is influenced by factors like infection, age, duration of infection and population studied.Fibrosis progression is grossly heterogeneous across study populations.It is suggested that HCV prognosis should be examined in homogeneous populations[157].

WHAT SVR REALLY REPRESENTS

SVR is a marker of viral eradication in HCV infection.The all-oral,] DAAs have drastically increased SVR rates compared to IFN-based treatment[158,159].In addition, SVR achieved after DAAs treatment has been shown to persist long term[63,160].SVR is indiscriminately characterized as a surrogate marker of clinical cure.

The National Institutes of Health (United States) defined surrogate endpoint or surrogate marker as a biomarker intended to substitute for a clinical endpoint.A first step for establishing a new surrogate marker is the investigation of the degree to which the candidate biomarker can explain or predict the effect of treatments on clinical endpoints measured in randomized clinical trials[161].

A Cochrane systematic review published in 2017 evaluated 51 trials comparing DAAs with placebo and/or no interventions.Most trials primarily reported on sustained virologic response and provided relatively limited data on clinically important outcomes and none at all on long-term effects.Meta-analysis of the effects of all DAAs showed no evidence of a difference in all-cause mortality between DAA recipients and controls with very low-quality evidence.Furthermore, all trials and outcome results were at high risk of bias.

It has been suggested that DAAs may reduce the number of patients with detectable virus in their blood, but no sufficient evidence from randomized trials exists that could allow us to understand how SVR affects long-term clinical outcomes.Therefore, SVR was considered to be an outcome that needs proper validation in randomized clinical trials.A laboratory measurement cannot be characterized as a surrogate marker without solid proof of a clinical outcome[162].Within a month, an unusual response to the Cochrane review appeared with EASL as both the author and the corresponding author! No names were mentioned, although they should have since EASL is a scientific society and cannot certainly write papers[163].At about the same time, the Cochrane review was fiercely criticized, but the critics admitted that the end point for most clinical trials of DAA therapies conducted has been SVR.They also pointed out that there were a few DAA trials that have examined clinical outcomes in decompensated patients with cirrhosis[164].

The Cochrane team in fact substantiated their argument on both SVR and on the effect of DAAs on mortality[165].They correctly pointed out that SVR had never been validated and even failed such validation in one analysis of long-term IFN intervention[166].Moreover, it was pointed out that quality of life is a completely subjective outcome, and its assessment needs blinded random controlled trials with unbiased patients[167].This is very difficult to be implemented in the case of DAAs as advertisements have promised a cure even for asymptomatic patients.It was also pointed out that the use of the word ‘cure’ was inappropriate.They argued that although SVR is a good prognostic sign, it has no validation as a surrogate outcome[168].

There are two critical points that require further analysis.The first is the question of randomized controlled trials, and the second is the use of the word ‘cure.’ The second is easier to answer as patients who achieve SVR can relapse years later with genetically identical viruses, suggesting that the virus possibly existed in a latent form inside the body, and so patients who achieve SVR can still progress to end-stage liver disease[169,170].A certain number of patients with compensated or decompensated cirrhosis show a deterioration of liver function[43,171,172] or display persistent hepatic inflammation or progress to cirrhosis despite SVR[173].Not only fibrosis or inflammation but also the development of HCC in patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis may continue in the presence of SVR[174,175] and in non-cirrhotic patients with a FIB-4 score ≥ 3.25[176].

In addition, achievement of SVR, characterized as ‘cure,’ has indeed been associated with reduced mortality among cirrhotic patients, but nonetheless it remains higher than general population mortality[146].Recent reports indicate that HCV patients may also die from liver-related complications even after SVR[154,177].Likewise, all-cause mortality is still high after SVR in cirrhotic patients[178].SVR after IFN-based treatment offered no survival benefit after 10 years of follow-up even in the specific group of hemophiliacs[142].

The other question is more difficult to answer, as prospective randomized controlled studies are extremely difficult, if not impossible, to organize in the case of DAAs.The very existence of many confounding factors intervening in the progress and outcome of HCV infection makes the whole project very difficult indeed.Two recent follow-up studies may exemplify the situation.In patients studied for the incidence of HCC, age, gender, cirrhosis and aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index were predictors of HCC in multivariate analysis, while SVR was not[179].In the same group of patients, diabetes proved to be a significant risk factor for disease progression in certain subgroups of patients without cirrhosis or compensated cirrhosis.Moreover, the absence of SVR was not an important risk factor[180].

A beneficial effect of SVR after DAA treatment on diabetes prevention and the short-term outcome of metabolic alterations has been reported by some studies.A recent review however argued that this effect may not be maintained in the long term, or more importantly this effect may not have any real clinical impact in liver disease[181].

The best conclusions that can be presented so far come from a recent prospective study but not a randomized trial comparing patients who achieve SVR with those that fail.After an extensive adjustment for a large number of variables, administration of DAAs was associated with a decrease in all-cause mortality and HCC but not with decompensated cirrhosis[182].

Data from the extensive Italian RESIST-HCV cohort similarly indicated that in patients with Child-Pugh B cirrhosis, the rate of liver decompensation was not associated with SVR[183].The need for extensive adjustments in different groups of patients may produce conflicting results.In a different study of patients with HCC from the same group, SVR was also a significant predictor of hepatic decompensation apart from being a predictor of survival and HCC recurrence[184].

SVR was a favorable prognostic marker of fibrosis decrease in a study based on liver elasticity measurements.However, progression of liver stiffness despite viral clearance was observed in 17% of patients[185].

Similarly, despite improvements in MELD score with DAA treatment that allowed the removal of almost a fifth of candidates from the transplantation list, many HCVinfected patients with SVR and decompensated cirrhosis still die or have a liver transplantation[186].In a longer follow-up of the same delisted patients due to their clinical improvement after DAAs, approximately 4% were either relisted because of disease progression or died due to the development of HCC[187].

In another study of HCV cirrhosis, SVR was associated with an improved MELD score in 37% of patients, but MELD was aggravated in 22% and stayed unchanged in the remaining 41%[38].These results were verified in another real world study of patients with advanced/decompensated cirrhosis treated with DAAs and a median follow-up of 4 years.After SVR, only marginal improvements in MELD at a clinically meaningful decrease were found in 29% of patients who might still remain at high risk of decompensation[155].These are examples of SVR use as a surrogate marker of a laboratory index rather than a specific clinical outcome.

Despite the previous reservations as to the use of SVR as a surrogate marker, recent guidelines of the two major liver disease associations equate SVR with successful clinical treatment[89,188].In accordance to these guidelines, investigators concluded that successful treatment of HCV translates into a significant mortality benefit in a very large study of HCV mono-infected patients without advanced fibrosis.Patients were stratified according to FIB-4 measurements.SVR patients with FIB-4 < 1.45 had a 46% reduction in mortality compared to no SVR patients, while patients with a FIB-4 between 1.45 and 3.25 had a 63.2% reduction in mortality rates.However, data were not based on liver biopsies as a basal stratification point, and this is a serious disadvantage.Another finding is that patients with no SVR die less compared to untreated patients, which is hard to explain[189].Conversely, SVR was associated with a reduction in fibrosis, but no association of fibrosis with mortality was reported.Finally, since only 14% of patients were re-biopsied, steatosis was not assessed[190].

A review on the reinfection rates after SVR with DAAs clearly states that SVR corresponds to a definitive cure of HCV infection as the incidence of late recurrent viremia is low[61].This is clearly different from another recent review stating that DAAs have been efficient in curing patients with chronic hepatitis C[191].A recent report on long-term results of DAAs avoids the words cure and surrogate marker, stating that despite excellent SVR rates there was a considerable overall mortality and liver-related mortality as well as decompensation incidence after 28 mo of follow-up[192].Even those supporting that SVR has been proven to be associated with reduced liver events and reduced overall mortality cannot support that SVR is a surrogate marker of the clinical cure of the patient[193].

The advent of liver stiffness measurements with the resultant substantial reduction of liver biopsies has not allowed for an accurate estimation of the effects of DAAs in patients with F1-F2 fibrosis.As rightly pointed out in a very recent review, only after long-term follow-up of large real-life cohorts of patients with mild to moderate fibrosis will we be able to confirm the real impact of SVR[194].

A very recent prospective multicenter study of 226 patients with HCV-related cirrhosis and clinically significant portal hypertension has shown that liver stiffness markedly decreased after SVR but did not correlate with hepatic venous pressure gradient changes.Ninety-six weeks after SVR, clinically significant portal hypertension may persist in up to 53%-65% of patients indicating a persistent risk of decompensation[195].These findings verify previous reports from the same group, also confirmed by other investigators, indicating that hepatic venous pressure gradient measurement is a better prognostic factor than SVR in advanced liver disease[196,197].

The conclusion is that no randomized trials exist so far, and only a few trials are actually prospective.Furthermore, it is clear that a considerable number of liverrelated incidents may occur despite SVR.We feel therefore that there is no justification of referring to SVR as a surrogate marker or as an equivalent to clinical cure for HCV patients.SVR should only be used as a favorable prognostic marker or as a marker of viral cure for HCV.

As mentioned before, HCV infection may have a relatively benign outcome without the presence of harmful confounding factors, namely alcohol, metabolic syndrome, HCV/HIV coinfection and liver iron.

EFFECT OF ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION IN HCV-RELATED FIBROSIS AND CIRRHOSIS

Earlier studies have shown that the prevalence of HCV is 3-30 times higher in alcoholics than the general population.Alcohol abuse is an independent factor of HCV progression.Advanced fibrosis and higher probability of developing cirrhosis and HCC have been reported for those with heavy alcohol consumption compared with non-drinkers[198-203].

In Dionysos, an extensive study of HCV in the general population in Northern Italy reported an association between alcohol and severity of HCV-associated liver disease.Alcohol consumption higher than 30 g/d aggravated the natural course of the disease significantly[204].Overall, at least in Western countries, approximately 60% of HCV patients have a past history of alcohol use.Chronic consumption of more than five drinks per day increases the rate of liver fibrosis[205].

Even lower alcohol intake increases HCV viremia and hepatic fibrosis[206].An interesting report of HCV patients was based on pairs of liver biopsies with a median time of 6.3 years between them.Alcohol consumption during the period between the biopsies was low (median 4.8 g ethanol/d.Deterioration of fibrosis was associated with higher total alcohol intake and higher drinking frequency between the biopsies[207].The fact that even low amounts of alcohol intake may lead to fibrosis progression has been recently reviewed[208].

An early study of HCV patients with elevated alanine aminotransferase has convincingly demonstrated that these patients had severe fibrosis associated with high alcohol consumption.Interestingly, all 3 patients who had cirrhosis and persistently normal alanine aminotransferase were also heavy drinkers[209].Other studies have also confirmed that total life-time alcohol consumption was independently associated with cirrhosis[210].A large observational study in five European countries confirmed the reports on the detrimental effects of alcohol on liver fibrosis irrespective of differences in biopsy use and preferred scoring systems[211].There was a 2-3-fold greater risk of liver cirrhosis and decompensated liver disease in the alcoholconsuming group.Progression to cirrhosis and decompensation was much faster in alcoholics with HCV compared to non-drinkers[212].A liver biopsy was performed on 86 heavy alcohol drinkers (80 g or more of ethanol/d for at least 10 years) with or without HCV infection.Higher intralobular necrosis and periportal inflammation was found on the liver histology of drinkers.Importantly, the development of cirrhosis was related more to the amount of alcohol intake than to the presence of HCV infection[213].Among 1620 HCV patients, the fraction of cirrhosis attributable to heavy alcohol intake was 36.1% and exceeded 50.0% among those who had engaged in heavy alcohol use at some point.AUDs contributed to approximately 70% of liver-related complications in young and middle-aged adults with HCV infection.An additional 15% was attributed to metabolic syndrome.Importantly, alcohol rehabilitation and abstinence reduced liver complications by 60% and 78%, respectively[214].

In addition to fibrosis and cirrhosis the risk of decompensation is also increased after alcohol.Data suggested that heavy, but not moderate, alcohol intake was associated with a higher risk for hepatic decompensation in patients with cirrhosis than HCV infection was[215], a finding confirmed in a population study of HCVinfected individuals.Age-adjusted decompensated cirrhosis incidence was considerably higher in people with AUDs in British Columbia, New South Wales and Scotland; AUD was present in 28%, 32% and 50% of those with decompensated cirrhosis, respectively[216].A very recent meta-analysis also verified that alcohol is strongly associated with HCV cirrhosis decompensation.Data from 286641 people with chronic HCV infections, of whom 22.3% with AUDs, showed that AUD diagnosis was associated with a 3.3-fold risk for progression of liver disease.Almost 4 out of 10 decompensated liver cirrhosis cases were attributable to an AUD[217].Interestingly, similar findings were reported in a very recent study on the effects of alcohol in patients with HBV[218].

The effect of alcohol on response to treatment with DAAs was recently reported.The baseline risk factors related to the success of DAAs were studied in 4946 HCV patients.They found that obesity, diabetes and alcohol consumption were associated with persistent liver enzyme elevation after SVR[219].

Earlier research also showed that HCC development increased as a result of the combined effect of alcohol and HCV infection[220].Alcohol intake was almost universally considered as a critical factor in the still unresolved dispute of HCC occurrence and recurrence after treatment with DAAs[221,222].

Τhe most important aspect of the involvement of alcohol consumption in the natural history of chronic HCV infection is its effect on mortality.Τhe risk of death in HCV patients is increased by 40% if alcohol abuse is also present[223].HCV patients admitted to the hospital with alcohol-related problems have doubled in-hospital mortality rates[224].Mortality rate was worst for alcoholic cirrhosis with concomitant HCV even after adjustment for age and gender[225].In a long-term study of cirrhosis of different etiologies from Sweden, the lowest 10-year transplantation-free survival was found in cryptogenic cirrhosis (11%) and in alcoholic cirrhosis combined with hepatitis C (12%)[226].The attributable risk of AUDs was 68.8% of 6677 liver deaths of patients infected by HCV.Moreover, liver-related mortality increased faster for individuals with AUDs[214].

The all-cause mortality was 1.9 times higher compared to the general population in patients with HCV followed up for an average of 5.2 years after SVR.Increased mortality was associated with either heavy alcohol use or injection of drugs.Patients without these behavioral markers had equal survival to the general population[146].Similar findings were also reported in a very recent study from the United States.Survival analysis demonstrated that there was a significant association between unhealthy drinking and lower survival compared with non-drinking[227].

Conclusions are similar when patients with AUDs were evaluated for the effects of the concomitant presence of HCV infection.In a small study of hospitalized alcoholic hepatitis patients, the presence of HCV was a significant risk factor for a poor outcome at 6 mo, even after adjustment for disease severity and treatment[228].The same group reported that patients with alcoholic hepatitis had a higher prevalence of HCV compared with the general population and that the presence of HCV infection also predicted a higher mortality[229].In a more recent investigation, the overall mortality rate was significantly higher among HCV-positive alcoholic patients than among HCV-negative patients, and the same was true for their respective liver-related mortality.Survival time for the HCV-infected patients was 34% less[230].These findings are usually not taken into account in Markov models of cost-effectiveness, and therefore estimates may be exaggerated[86].

Research has focused on the mechanism of the synergistic effect of alcohol and HCV in view of the above findings.An increase of apoptotic cell death in hepatocytes of HCV-infected patients has been demonstrated.Apoptosis was further upregulated by active ethanol consumption[231].Another critical mechanism of HCV-alcohol synergy is the effect both have on innate immunity.Dendritic cells, the critical cell type in antigen presentation, have shown to be a major target for HCV and ethanol with a resultant dysfunction of CD4 and CD8 T cells[232,233].The common molecular mechanisms of the synergy between alcohol and HCV also include the interference with cytokine production, lipopolysaccharide-TLR4 signaling and reactive oxygen species production.Increased oxidative stress seems to be the dominant mechanism for this synergism between alcohol and HCV[203,234].Recently, the synergistic effect of alcohol and HCV on alcohol-induced ‘leaky gut’ as well as their effects on miR-122 and immune dysregulation have been investigated[235].

An important mechanism still under intense investigation is autophagy.Both alcohol and HCV infection could induce cellular autophagy in liver cells, a process that is considered to be essential for productive HCV replication.It would seem, at least from experimental studies, that alcohol promotes HCV replication through activation of autophagy[236].

The problem of HCV-alcohol interconnections has been extensively reviewed[237,238].

HCV AND METABOLIC SYNDROME

Other factors that might interfere with the outcome of HCV infection are related to metabolic syndrome.

Previous reports have indicated that obesity and diabetes occur more frequently in HCV patients.Both conditions result in fatty liver.Steatosis is associated with either metabolic alterations like IR and visceral obesity (metabolic steatosis) or a direct cytopathic effect of the virus mostly genotype 3 (viral steatosis), which is strongly related to serum viral load[239-243].

There is evidence that metabolic syndrome is directly linked to HCV infection[244].Visceral adiposity index is a marker of adipose dysfunction in HCV patients.It is associated with steatosis and necro-inflammatory activity and has a direct correlation with viral load and SVR.In fact, visceral adiposity index represents a measure of the metabolic syndrome[245,246].

There is also indirect evidence connecting metabolic syndrome with HCV.Hyperuricemia is associated with the metabolic syndrome.Its association with HCV infection is additional indirect evidence of their relationship.As expected, body mass index (BMI) is also a factor associated with hyperuricemia in HCV patients[247].Hyperuricemia has been independently associated with severity of steatosis, indirectly affecting liver damage[248].There are conflicting recent reports on the effect of DAA treatment on hyperuricemia.Uric acid levels were significantly decreased in chronic HCV patients after viral eradication.The improvement was particularly enhanced in patients with mild liver disease[249].On the contrary, uric acid levels were moderately increased after HCV eradication in patients with hyperuricemia.Thus, it was considered an adverse effect to DAAs containing ribavirin, potentially leading to side effects such as renal impairment[250].The reason for this discrepancy is unknown.

Carotid plaques are also an indirect indication of metabolic syndrome, although other pathophysiological mechanisms may be involved.The risk of a person with HCV infection developing carotid plaques is approximately 3.94 times the risk of an uninfected person[251].More importantly, metabolic syndrome is an independent risk factor of HCV mortality[252,253].An extensive review on the association between HCV and metabolic syndrome has recently been published[254].

Obesity-steatosis

According to the WHO, obesity is an excessive or abnormal accumulation of fat.It has been suggested that this condition is a 21stcentury pandemic, with a prevalence of 1.9 billion cases worldwide, while almost 40% of the adult population in industrialized countries is overweight[255].

Liver steatosis affects up to 80% of patients with HCV infection[256].In a recent cross-sectional study, 66% of HCV patients were obese and almost one-third fulfilled the criteria of metabolic syndrome.Of note is the fact that 67% of them were either current or past heavy drinkers[257].HCV has been closely associated with obesity and steatosis.Obese HCV patients had higher grades of steatosis and advanced fibrosis[258].Earlier and more recent studies have proven beyond any doubt that obesity, steatosis and liver inflammation are interconnected[240,259-262].At the same time, the fibrosis progression rate was higher when excessive steatosis was present in the first liver biopsy[263].The association between steatosis and fibrosis was dependent on a simultaneous association between steatosis and liver inflammation[264].

The association of BMI with steatosis and fibrosis may have important therapeutic implications[265] because weight reduction improved both biochemistry and the Knodell fibrosis score[266].In the era of IFN-based treatments, obesity and steatosis were associated with reduced SVR[267-271].

Cirrhosis-HCC

A recent Swedish population-based study of cirrhosis identified that irrespective of etiology the most common comorbidities at diagnosis were arterial hypertension (33%), type 2 diabetes (T2DM) (29%) and obesity (24%)[272].The metabolic syndrome and liver stiffness measurements were independent risk factors of HCV progression to cirrhosis[273].Indirect evidence that cirrhosis in HCV infection is related to metabolic syndrome comes from a prospective study indicating that dysregulation of various metabolic profiles preceded the ultimate development of cirrhosis[274].

There are data connecting the appearance of HCC with components of metabolic syndrome.The risk of HCC in HCV patients increases in proportion to their BMI, from underweight to obese[275].Individuals with a high BMI (≥ 25.0 kg/m2) accompanied by low triglyceride levels (< 160 mg/dL) had a significantly increased risk for liver cancer related mortality[276].In the DAA era, increase in HCC incidence after treatment has been associated with higher BMI and cirrhosis[277].A systematic review demonstrated a significant association between BMI and HCC risk.As expected steatosis was also associated with a higher risk of HCC[278].

In IFN-based treatment, response was diminished in overweight patients without other comorbidities.The group included children and teenagers[279].This however is not the case with DAAs as reported recently but is worth noting that the separation between obese and non-obese patients was set at a rather high BMI of 30[280].

Diabetes mellitus and IR

Several studies have verified that T2DM, IR and hepatic steatosis are highly prevalent in patients with genotype 1 HCV infection[246,278,281-283].In a large study of 710 patients with a known duration of infection, both overt diabetes and high serum glucose levels were associated with advanced fibrosis and a high fibrosis progression rate independent of alcohol consumption and other risk factors such as the duration of infection[244].IR was also associated with fibrosis[284].HOMA-IR was higher in advanced fibrosis than in mild.The number of lipid laden hepatocytes was also higher in cases of advanced fibrosis with increased HOMA-IR and BMI > 25.0 kg/m2[285,286].IR is associated with HCV infection in up to 80% of cases, and the risk of developing T2DM is twice as high compared to subjects without HCV[287].

Not only is HCV natural course aggravated by diabetes, but HCV infection is a significant risk factor for developing T2DM as well.Spontaneous or treatment-induced HCV clearance may reduce the risk of the onset of T2DM[288].

Another important aspect of the interaction between T2DM and HCV is the association with HCC development.Diabetics with HCV has a 2-3-fold increase in HCC risk[289-291].Maintenance of glycated hemoglobin level below 7.0% reduced the development of HCC[292].Diabetes was independently associated with both de novo HCC occurrence and HCC recurrence after DAA treatment[178,293].A systematic review of seven cohort and two case-control studies has confirmed the significant contribution of T2DM in the development of HCC in HCV-infected patients[278].

The presence of IR or overt diabetes has implications in the treatment of HCV[242] as it adversely affects the response to treatment with IFN-based therapies[294-296].However, HCV patients who achieved SVR after IFN-based therapy had an improvement of both HOMA-IR and HOMA-b[297].SVR12 rates are not affected by the presence of T2DM in DAA treated HCV patients[298].Recent evidence indicates that viral elimination by DAAs improves the increased IR and T2DM incidence by restoring alterations of glucose homeostasis induced by HCV.It should be noted however that IR may persist after SVR, particularly in patients with high BMI[299,300].

HCV patients have an altered serum lipid profile characterized by a reduction of total cholesterol, low-density lipoproteins and very-low-density lipoproteins[301].Viral eradication with DAAs may have improved HOMA-IR, but serum lipids were increased and the lipid profile worsened in a follow-up study of 24 wk after SVR.BMI did not change in this study[302].This was not the case in a larger study of 343 HCV patients with the same follow-up.In addition to increased serum cholesterol and lowdensity lipoprotein cholesterol, an increase in BMI was also observed.Serum glucose, HOMA-IR and HOMA-b were decreased.More importantly, one-third of patients with fasting hyperglycemia normalized serum glucose values, and almost half of diabetics improved glycemic control[303].A temporary IR increase during treatment with DAAs that went back to normal after treatment was reported, in contrast to lipids that remained increased[304].

In general, HCV steatosis occurs in association with multiple metabolic abnormalities like hyperuricemia, hypocholesterolemia, IR, arterial hypertension and expansion of visceral adipose tissue referred to as “HCV-associated dysmetabolic syndrome” and shares many underlying abnormalities with nonalcoholic liver disease[305].

There are some mechanistic explanations for the aforementioned findings.HCVassociated metabolic steatosis accelerates liver fibrosis progression and development of HCC by inducing liver inflammation and oxidative stress[306].Both pathways lead to increased fibrosis through induction of the connective tissue growth factor[307,308].HCV core protein and nonstructural protein 5A are implicated in the disturbance of lipid and glucose pathways that lead to steatosis, lipid abnormalities and metabolic syndrome[309].Moreover, HCV interferes directly and indirectly with insulin signaling that results in the production of proinflammatory cytokines[310].

HCV/HIV COINFECTION

HIV patients are very often coinfected with HCV.Prevalence of coinfection varies in different countries and among different subpopulations like PWID or hemophiliacs[311-313].HCV/HIV coinfection may interfere with some aspects of HCV natural course[314,315].HIV antiretroviral therapy (HAART) alone did not fully correct the adverse effect of HIV infection on HCV progress[316].

Mortality

In the HAART era, HCV coinfection increased the risk of mortality compared with HIV mono-infection possibly due to a more rapid progression of HCV in the coinfection group[317].

In a long-term follow-up study of HCV-infected hemophiliacs, HIV coinfected patients were compared to non-HIV patients for mortality after an average of 24 years.The adjusted risk ratio for death was significantly greater among HIV-positive than among HIV-negative patients after adjustment for alcohol use and HAART use was applied, indicating that HIV accelerates HCV disease progression[318].Failure to clear HCV led from rapid progression to decompensation in HCV/HIV coinfected patients[319].These findings were confirmed as HCV infection was independently associated with all-cause and liver-related mortality in HIV patients with alcohol problems, even when adjusting for alcohol and other drug use[320].In a very large retrospective study, a higher mortality of HCV/HIV coinfection compared to HCV mono-infection was reported.Moreover, the presence of HCV cirrhosis or complications from it were associated with four times greater mortality risk in HIV patients[321].A very recent study of people living with HIV (PLWH) and of those injecting drugs demonstrated the highest odds of HCV-positivity, which was an independent predictor of greater mortality[322].

An individual-based model of disease progression in HIV/HCV coinfected MSM has been developed.There was a gradual increase of liver-related deaths according to fibrosis state and the time treatment was initiated.Two percent of treated patients would die if treatment was initiated at stage F0 and 22% if treatment was deferred until F4.Similar gradual mortality increments were associated with the length of time individuals replicate HCV[323].

HCC development is associated with increased HCV mortality rates.Older age, cirrhosis and low current CD4 cell count were associated with a higher incidence of HCC in HCV/HIV coinfection[324,325].Furthermore, a recent prospective study demonstrated that HCV/HIV patients with compensated cirrhosis have similar risks for further end-stage liver disease and HCC with HCV mono-infected patients[15] provided they receive both HAART and DAA treatment[326].

Fibrosis

In the pre-DAA era, many studies based on paired liver biopsies demonstrated that hepatic fibrosis progressed more rapidly in HCV/HIV coinfection than in HCV monoinfected patients even after adjustment for alcohol consumption or duration of HCV infection[327-331].In a retrospective cohort study focusing on a PWID group of patients, HIV coinfection worsened the outcome of chronic HCV infection, increasing liver damage and decreasing sustained SVR after IFN therapy.Age and alcohol were cofactors associated with cirrhosis and mortality[332].Fibrosis progressed in a significant number of HCV/HIV coinfected patients even after DAA-induced SVR[333].

Not all studies agree with the above findings.After adjustment for daily alcohol use, HIV patients with HCV coinfection and BMI greater than 25 kg/m2had equal liver fibrosis to those without HIV but at an average onset of 9.2 years earlier[334].Hepatic steatosis increased faster and was associated with fibrosis progression only in HIV mono-infected patients but not in HIV/HCV coinfected ones.Diagnosis was based on liver stiffness measurements for fibrosis and controlled attenuation parameter for steatosis without histological documentation[335].Histological abnormalities were usually significantly milder in HCV/HIV coinfection with persistently normal alanine aminotransferase levels than those found in patients with high alanine aminotransferase, but this was not always the case as patients with persistently normal alanine aminotransferase levels also developed significant fibrosis[336].

The risk of advanced fibrosis increased at high levels of alcohol consumption[337].In this group of patients even low alcohol consumption was associated with advanced hepatic fibrosis[338].The impact of alcohol was recently verified.HIV/HCV coinfected patients had a higher prevalence of intermediate and advanced liver disease markers than HIV mono-infected patients.Advanced markers of liver disease were strongly connected to hazardous drinking for both men and women[339].

Genetic factors are also involved.Cirrhosis was more prevalent in IL28B CC genotype HCV/HIV infected patients than in patients with CT/TT genotypes, possibly indicating that IL28B CC carriers have a more rapid progression of HCVrelated fibrosis[340].

A number of studies have reported on the achievement of SVR in either observational studies or clinical trials, and the results were conflicting.A statistically significant difference in SVR12 response was observed between HCV mono-infection and HCV/HIV coinfection after DAAs (94% and 84%, respectively)[341].HCV/HIV coinfection response to DAAs was worse (86%) compared to HCV mono-infection (95%).This was possibly due to a higher rate of relapses among HCV/HIV coinfected subjects[342].

A high SVR12 was similar in a review of 11 real-world observational studies (90.8%) and 8 clinical trials (93.1%).There was no control group of HCV-mono-infection[343].A recent multicenter study of SOF/DCV from Brazil showed an SVR12 rate of 92.8% in an intention-to-treat analysis.There was no comparison with HCV mono-infected patients[344].A similar SVR12 of 94% was reported in a retrospective study from the United States.Substance abuse and diabetes, but not obesity, had a negative effect on treatment[345].Importantly, a recent paper stressed the fact that both adherence to HAART treatment and alcohol consumption should be carefully monitored in this group of patients.Furthermore, higher alcohol consumption per day was positively associated with HAART non-adherence[346].Interestingly, high coffee intake is probably associated with reduced liver fibrosis even in HCV/HIV coinfected patients with high alcohol abuse[347].

Clinical consequences after successful treatment with IFN-free regimens are limited.A Spanish group reported that successful SVR in HCV/HIV coinfected patients led to the same probability of liver complications with HCV mono-infection after a median follow-up of 21 mo[348].In addition, the same group reported that only successful SVR patients with > 14 kPa on liver stiffness measurement are among the few who develop a liver-related complication[349].

Strangely enough, HCV/HIV coinfected patients had a lower risk of HCC development compared to HCV-mono-infection after successful SVR in a follow-up study from the same group.This is hard to explain particularly because alcohol consumption and diabetes were the same, and the HIV-positive group included significantly more PWID[350].This is in slight disagreement with another study where HCV/HIV coinfected patients had a greater mortality risk and a similar risk of HCC development indicating that DAAs do not produce complete resolution of inflammatory and profibrogenic stimuli[326].