基于转录组的剑麻SSR标记开发与筛选

2021-07-20张燕梅李俊峰杨子平鹿志伟陆军迎周文钊

张燕梅 李俊峰 杨子平 鹿志伟 陆军迎 周文钊

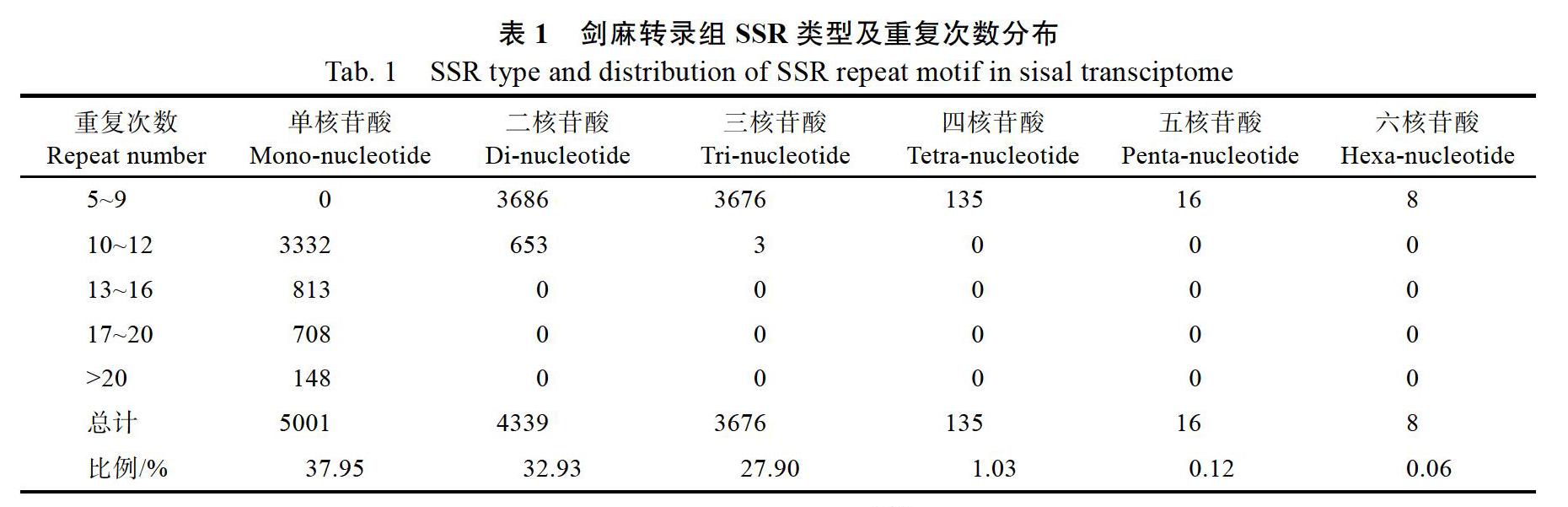

摘 要:本研究基于剑麻转录组测序获得的70 110条Unigene序列,采用MISA 1.0软件查找SSR位点,利用Primer 3.0设计SSR引物,通过聚丙烯酰胺凝胶电泳技术对其中的100对SSR引物有效性进行验证。总计获得了13 175个SSR位点,SSR的分布频率为15.61%。70 110条Unigene序列总计包括60种重复基元,其中单核苷酸重复为主导重复类型(37.96%),其次是二核苷酸重复和三核苷酸重复,比例分别为32.92%和27.90%,四核苷酸、五核苷酸、六核苷酸重复所占比例总计为1.21%。A/T、AG/CT和AGG/CCT分别为单核苷酸、二核苷酸和三核苷酸重复的优势基元。100对SSR引物中有68对引物可扩增出目标产物,其中18对引物在6份剑麻种质中表现出多态性,该结果为利用SSR分子标记技术开展剑麻种质资源鉴定、遗传多样性分析等奠定基础。

关键词:剑麻;转录组测序;SSR

中图分类号:S563.8 文献标识码:A

Abstract: In this study, the high-throughput sequencing of the transcriptome of sisal was used to seek SSR loci and de-velop SSR markers by MISA 1.0 and Primer 3.0 softwares, respectively, and preliminary primer verification and poly-morphic primer analysis were performed by vertical acrylamide gels. A total of 13 175 of SSR loci were found in the 70 110 unigene sequences. The SSR distribution frequency was 15.61%. In total, 60 repeat elements were obtained, among them, mono- nucleotides were the domiant repeat motif (37.96%), followed by di-nucleotides (32.92%), and tri-nucleotides repeats (27.90%), the other repeat types occupied 1.21% in all. The most dominant mono-nucleotide, di-nucleotide and tri-nucleotide repeat motif was A/T, AG/CT and AAG/TTC, respectively. Among the 100 pairs of SSR primers randomly selected from the designed SSR primers of Rema No. 1, sixty-eight pairs of primers could amplify the expected size bands, and eighteen primers showed polymorphism among six sisal germplasms. The obtained primers would provide effective molecule markers for genetic diversity analysis and germplasm identification of sisal.

Keywords: sisal; RNA-seq; simple sequence repeats

DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-2561.2021.05.009

劍麻是一种重要的热带纤维作物,有重要的经济价值。由于剑麻自然条件下变异频发且倍性复杂[1],现有保存的种质资源中,主要是通过麻园选育、杂交和引种获得,遗传背景模糊,命名极不规范,有的很难从表型加以辨别,给剑麻种质资源的保存利用以及育种工作带来极大不便。分子标记技术的出现给遗传育种研究注入了新的活力,并且在剑麻品种鉴定以及遗传多样性分析等方面得到广泛的应用[2-8]。

微卫星DNA(microsatellite DNA)又称简单重复序列(simple sequence repeat,SSR),是由1~6个核苷酸为重复单位串联而成的长达几十个核苷酸的重复序列,按其来源可分为基因组SSR(gSSR)和表达序列标签SSR(EST-SSR)。与其他分子标记相比,SSR标记具有多态性高、重复性好、共显性遗传等优点,可以区分纯合子和杂合子,广泛应用于遗传多样性分析[9]、种质资源鉴定[10]以及遗传作图[11]等领域。目前剑麻中报道的SSR引物仅有7对,由于剑麻SSR引物偏少,获得的信息量有限,因此,开发剑麻SSR标记引物对开展剑麻遗传研究十分必要。剑麻基因组较大(1Cx≈7.5 pg)[1],基因组信息未知,在短时间内开发gSSR标记几乎不可能,随着生物信息学和测序技术的飞速发展,EST序列数据剧增,利用EST序列开发SSR标记引物成为可能,并且在其他物种中已有成功的报道[12]。鉴于此,本研究基于前期获得的剑麻转录组序列,利用MISA软件查找SSR位点,开发剑麻SSR标记引物,解决剑麻SSR标记引物缺乏等实际问题,同时为剑麻遗传研究奠定基础。

1 材料与方法

1.1 材料

1.1.1 转录组数据来源 剑麻转录组序列主要来源于本课题前期获得的‘热麻1号的70 110个Unigenes序列。

1.1.2 植物材料 植物材料为一年生的‘H.11648‘肯1‘肯2‘热麻1号‘无刺番麻和普通剑麻走茎苗。每份材料取3~5株,每株取1 g叶片等量混合后用于提取基因组DNA。

1.2 方法

1.2.1 DNA提取 DNA提取采用天泽公司的柱式植物DNAout试剂盒提取,实验材料用液氮快速研磨后取少量粉末,加入裂解液,经抽提、漂洗后过柱,洗脱后4 ℃保存备用,具体操作参照试剂盒说明书。

1.2.2 SSR位点查找 采用MISA 1.0软件对每个Unigene进行简单序列重复(SSR)位点查找,SSR位点筛选参数为:单核苷酸的重复次数大于或等于10次,二核苷酸重复次数大于或等于6次,三核苷酸、四核苷酸、五核苷酸、六核苷酸的重复次数大于或等于5次。

1.2.3 SSR引物开发 采用Primer Premier 3.0设计引物,引物长度18~25 bp,GC含量为40%~ 60%,退火温度Tm为56~65 ℃,预期产物长度为100~300 bp,尽量避免二聚体和发卡结构。引物由上海生工生物工程有限公司合成。

1.2.4 SSR引物有效性验证 随机选取100对SSR引物,以‘H.11648‘肯1‘肯2‘热麻1号‘无刺番麻和普通剑麻等6份种质的基因组DNA混合池为模板,进行PCR扩增,扩增产物用8%的聚丙烯酰胺凝胶电泳检测,150 V,2.5 h后取下胶板,银染后拍照保存。PCR扩增程序为:首先94 ℃(15 s),60 ℃ 15 s,72 ℃ 30 s,16个循环,每个循环退火温度降低0.7 ℃;然后进入下一个扩增阶段:94 ℃ 15 s,50 ℃ 15 s,72 ℃ 30 s,15个循环,最后72 ℃延伸60 min,扩增产物加入1/3体积的上样缓冲液,混匀后4 ℃保存备用。

1.2.5 SSR引物多态性筛选 分别以‘H.11648‘肯1‘肯2‘热麻1号‘无刺番麻和普通剑麻等6份种质的基因组DNA为模板,对检测有目标产物条带的SSR引物进行扩增,扩增产物经8%聚丙烯酰胺凝胶电泳检测,银染后拍照保存。扩增程序和检测方法同SSR引物有效性验证。

2 结果与分析

2.1 剑麻SSR位点的分布与数量

‘热麻1号的70 110条Unigenes序列全长总计45 255 938 bp,经MISA分析后发现有10 946条Unigenes序列共含有13 175个SSR位点(1/3.43),SSR发生频率(含SSR的Unigene数/总Unigene数)为15.61%,SSR出现频率(SSR位点数/总Unigene数)为18.79%,其中有1 848条序列含有2个或2个以上的SSR位点,803个SSR位点以复合形式存在。‘热麻1号‘转录组SSR类型丰富,单核苷酸至六核苷酸重复均存在,其中单核苷酸为主导重复基元,比例为37.96%,其次是二核苷酸和三核苷酸重复,比例分别为32.92%和27.90%,四核苷酸、五核苷酸和六核苷酸比例较低,分别为1.03%、0.12%和0.06%。从基元重复次数来看(表1),‘热麻1号转录组SSR单核苷酸重复中10~12次重复较多,占单核苷酸SSR的66.63%,二核苷酸至六核苷酸重复中5~9次重复较多,分别占二核苷酸的84.95%,三至六核苷酸的100%。

2.2 剑麻SSR基序频率特征及重复类型

‘热麻1号的13 175个SSR位点,共包含60种重复基元,其中单核苷酸、二核苷酸、三核苷酸、四核苷酸、五核苷酸和六核苷酸的重复基元数分别为2、4、10、23、13和8種。单核苷酸重复基元主要有A/T和C/G两种类型,其中A/T类型4936个,占单核苷酸重复的98.70%。二核苷酸有AG/CT、AC/GT、AT/AT、CG/CG等4种重复类型,其中AG/CT最多,占二核苷酸重复类型的86.01%,CG/CG比例最低,为1.06%(图1)。三核苷酸有10种重复类型,其中AAG/CTT、AGG/CCT、AGC/TCG、CCG/CGG所占比例较高,分别为21.68%、21.41%、14.99%、12.68%,ACT/AGT比例最低,为0.46%(图1)。四核苷酸有23种重复类型,除AAAG(22.22%)、AAAT(19.26%)、AAAC(9.63%)、ACAT(8.89%)和AGCG(7.41%)外,其他每种类型数量均在1~5之间,出现频率较低。五核苷酸和六核苷酸分别有13和8种重复类型,每种重复类型数量均为1。

2.3 SSR引物有效性验证

利用6份剑麻种质基因组DNA混合池为模板,随机选取100对SSR引物进行检测分析,有68对引物可扩增出稳定的目标产物条带,表明开发的SSR引物有效,且引物扩增效率为68%(图2,表2)。

2.4 多态性SSR引物筛选

分别以6份剑麻种质基因组DNA为模板,对68对有目标产物条带的SSR引物进行扩增,经聚丙烯酰胺凝胶电泳检测后筛选出18对有多态性的SSR引物,多态性比率为26.47%(图3),多态性引物及其DNA序列见表3。

3 讨论

剑麻作为热区重要的经济作物和景天酸代谢的模式物种,有非常重要的经济和理论价值[13]。然而由于剑麻遗传背景复杂,基因组信息缺乏,使 剑麻的遗传改良研究相对滞后。本研究从‘热麻1号的70 110条Unigene序列中搜索到13 175个SSR位点,分布于10 946条Unigene序列上,SSR出现频率为18.79%,SSR发生频率为15.61%,平均距离为3.43 kb。与其他植物相比,剑麻的出现频率与水牛草(14.41%)[12]和不结球白菜(18.44%)[14]相当,高于小麦(7.41%)[15],甜叶菊(2.26%)[16]和红松(7.43%)[17],白芷(13.18%)[18]等,但明显低于芒果[19],枇杷(22.02%)[20]和橡胶树(35.58%)[21],不同物种间SSR出现频率不同主要与SSR搜索时使用的软件工具,重复类型以及最小重复数,长度标准以及分析数据量的大小不同有关[22-23]。

本研究結果表明,剑麻转录组中单核苷酸SSR数量最多(37.96%),与红松[17]和太行菊[24]等植物中报道的相似,与竹子[25]、老芒麦[26]、水牛草[12]以及水稻、小麦等单子叶植物[27]不同。除单核苷酸外,剑麻中二核苷酸SSR数量较多(32.93%),二核苷酸优势重复基元为AG/CT,这与天麻[28]、小麦[27]、老芒麦[26]等大多数单子叶植物相同,Kumpatla等[23]对49种双子叶植物SSR分析表明,二核苷酸重复为主导重复类型,其次为三核苷酸重复或单核苷酸重复,重复类型非冗余EST序列包含SSR数量排名前20的SSR重复基元进行分析发现,AG/GA/CT/TC为20种双子叶植物样本中的二核苷酸优势重复基元,AAG/AGA/GAA/ CTT/TTC/TCT为三核苷酸优势基元,这与本研究结果相似,Morgante等[27]和Varshney等[29]研究证实植物eSSR中AG/CT为二核苷酸重复的优势重复基元,这与本研究结果非常吻合,但本研究中CG重复比例较低,而Morgante等[27]研究显示AT重复比例较低。剑麻中三核苷酸比例次于单核苷酸和二核苷酸,以AAG/TTC、AGG/CCT为优势基元。这与Morgante等[27]报道的在水稻、小麦、玉米等单子叶植物中三核苷酸比例最高且CCG为优势基元结果不同,这种现象在多种植物中均有报道[23]。Kumpatla等[23]分析认为,不同物种间以及同一物种内主导核苷酸重复类型以及优势基元不同,主要原因可能与SSR分析过程中采用的搜索工具、分析时设置的参数标准以及分析时数据量的大小等有关。此外,3UTR富含三核苷酸和四核苷酸,5UTR富含二核苷酸和三核苷酸,EST序列中3UTR和5UTR的比例对核苷酸重复类型也存在影响。

综上所述,本研究利用现有的剑麻EST-SSR序列开发SSR标记引物是可行且有效的,并且本研究结果是对剑麻SSR引物的一个很好补充,利用筛选的18对SSR引物可以开展剑麻种质资源鉴定、遗传多样性分析以及亲本鉴定研究,若要开展剑麻遗传图谱构建和比较作图等,还需要筛选更多的SSR引物。

参考文献

[1] Robert M L, Lim K Y, Hanson L, et al. Wild and agronomi-cally important Agave species (Asparagaceae) show proportional increases in chromosome number, genome size, and genetic markers with increasing ploidy[J]. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 2008, 158(2): 215-222.

[2] Gil V K, González C M, Martínez de la V O, et al. Analysis of genetic diversity in Agave tequilana var. azul using RAPD markers[J]. Euphytica, 2001, 119(3): 335-341.

[3] Gil-Vega K, Díaz C, Nava-Cedillo A, et al. AFLP analysis of Agave tequilana varieties[J]. Plant Science, 2006, 170(4): 904-909.

[4] Vargas-Ponce O, Zizumbo-Villarreal D, Martínez-Castillo J, et al. Diversity and structure of landraces of agave grown for spirits under traditional agriculture: a comparison with wild populations of A. angustifolia (agavaceae) and commercial plantations of A. tequilana[J]. American Journal of Botany, 2009, 96(2): 448-457.

[5] Rodríguez-Garay B,Lomelí-Sención J A, Tapia-Campos E, et al. Morphological and molecular diversity of Agave tequilana Weber var. Azul and Agave angustifolia Haw. Var. Line?o[J]. Industrial Crops and Products, 2009, 29(1): 220-228.

[6] Gao J, Luo P, Guo C, et al. AFLP analysis and zebra disease resistance identification of 40 sisal genotypes in China[J]. Molecular Biology Reports, 2012, 39(5): 6379-6385.

[7] Trejo L, Limones V, Pe?a G, et al. Genetic variation and relationships among agaves related to the production of Te-quila and Mezcal in Jalisco[J]. Industrial Crops and Products, 2018, 125: 140-149.

[8] Lindsay D L, Edwards C E, Jung M G, et al. Novel microsatellite loci for Agave parryi and cross-amplification in Agave palmeri (Agavaceae)[J]. American Journal of Botany, 2012, 99(7): e295-e297.

[9] Bibi A C, Gonias E D, Doulis A G. Genetic diversity and structure analysis assessed by SSR markers in a large collection of Vitis cultivars from the island of Crete, Greece[J]. Biochemical Genetics, 2020, 58(2): 294-321.

[10] Zhao Y, Wang Y, Wang L, et al. Molecular identification of mung bean accessions (Vigna radiate L.) from Northeast China using capillary electrophoresis with fluores-cence-labeled SSR markers[J]. Food and Energy Security, 2019, 9(1): e182

[11] Wang Y, Jia H M, Shen Y T, et al. Construction of an anc-horing SSR marker genetic linkage map and detection of a sex-linked region in two dioecious populations of red bay-berry[J]. Horticulture Research, 2020, 7: 53.

[12] Abdi S, Dwivedi A, Shi S, et al. Development of EST-SSR markers in Cenchrus ciliaris and their applicability in study-ing the genetic diversity and cross-species transferability[J]. Journal of Genetics, 2019, 98: 101.

[13] Stewart J R. Agave as a model CAM crop system for a warming and drying world[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2015, 6: 684.

[14] 楊丹青, 何晓丽, 杜志杰, 等. 基于不结球白菜转录组EST-SSR标记开发及多态性分析[J]. 农业生物技术学报, 2020, 28(1): 13-21.

[15] Peng J H, Lapitan N L V. Characterization of EST-derived microsatellites in the wheat genome and development of eSSR markers[J]. Funct Integr Genomics, 2005, 5(2): 80-96.

[16] Cosson, Patrick, Hastoy Cécile, Errazzu L E, et al. Genetic diversity and population structure of the sweet leaf herb, Stevia rebaudiana B., cultivated and landraces germplasm assessed by EST-SSRs genotyping and steviol glycosides phenotyping[J]. BMC Plant Biology, 2019, 19(1): 436.

[17] Li X, Liu X T, Wei J T, et al. Development and transferabil-ity of EST-SSR markers for Pinus koraiensis from cold-stressed transcriptome through Illumina sequencing[J]. Gene, 2020, 11: 500.

[18] Liu Q Q, Lu Z Y, He W, et al. Development and characteri-zation of 16 novel microsatellite markers by transcriptome sequencing for Angelica dahurica and test for cross-species amplification[J]. BMC Plant Biology, 2020, 20: 152

[19] 罗 纯, 武红霞, 姚全胜, 等. 芒果转录组中SSR位点信息分析与引物筛选[J]. 热带作物学报, 2015, 36(7): 1261-1266.

[20] Li X Y, Xu H X, Feng J J, et al. Development and applica-tion of genic simple sequence repeat markers from the tran-scriptome of loquat[J]. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science, 2014, 139(5): 507-517.

[21] Mantello C C, Cardoso-Silva C B, Da Silva C C, et al. De novo assembly and transcriptome analysis of the rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis) and SNP markers development for rubber biosynthesis pathways[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(7): e102665.

[22] Varshney R K, Graner A, Sorrells M E. Genic microsatellite markers in plants: features and applications[J]. Trends in Biotechnology, 2005, 23(1): 48-55.

[23] Kumpatla S P, Mukhopadhyay S. Mining and survey of simple sequence repeats in expressed sequence tags of dicotyledonous species[J]. Genome, 2005, 48(6): 985-998.

[24] Chai M, Ye H, Wang Z, et al. Genetic divergence and rela-tionship among Opisthopappus species identified by devel-opment of EST-SSR markers[J]. Frontiers in Genetics, 2020, 11: 177.

[25] Bhandawat A, Sharma V, Singh P, et al. Discovery and utilization of EST-SSR marker resource for genetic diversity and population structure analyses of a subtropical bamboo, Dendrocalamus hamiltonii[J]. Biochemical Ge-netics, 2019, 57(5): 652-672.

[26] Zhang Z, Xie W G, Zhao Y Q, et al. EST-SSR marker de-velopment based on RNA-sequencing of E. sibiricus and its application for phylogenetic relationships analysis of seventeen Elymus species[J]. BMC Plant Biology, 2019, 19: 235.

[27] Morgante M, Hanafey M, Powell, W. Microsatellites are preferentially associated with nonrepetitive DNA in plant genomes[J]. Nature Genetics, 2002, 30: 194-200.

[28] Wang Y, Shahid M Q, Ghouri F, et al. Development of EST-based SSR and SNP markers in Gastrodia elata (herbal medicine) by sequencing, de novo assembly and annotation of the transcriptome[J]. 3 Biotech, 2019, 9(8): 292.

[29] Varshney R K, Thiel T, Stein N, et al. In silico analysis on frequency and distribution of microsatellites in ESTs of some cereal species[J]. Cellular and Molecular Biology Letters, 2002, 7(2a): 537-546.

責任编辑:黄东杰