Anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation in heart failure patients:balancing between Scylla and Charybdis

2021-06-18GrigoriosTsigkasAnastasiosApostolosStefanosDespotopoulosGeorgiosVasilagkosAngelikiPapageorgiouEleftheriosKallergisGeorgiosLeventopoulosVirginiaMplaniIoannaKoniariDimitriosVelissarisJohnParissis

Grigorios Tsigkas, Anastasios Apostolos, Stefanos Despotopoulos, Georgios Vasilagkos,Angeliki Papageorgiou, Eleftherios Kallergis, Georgios Leventopoulos, Virginia Mplani,Ioanna Koniari, Dimitrios Velissaris, John Parissis

1. Department of Cardiology, University Hospital of Patras, Patras, Greece; 2. Department of Cardiology, University Hospital of Heraklion, Heraklion, Greece; 3. Department of Cardiology, University Hospital of South Manchester, NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester, United Kingdom; 4. Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital of Patras, Patras,Greece; 5. Second Department of Cardiology, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Attikon University Hospital,Athens, Greece

ABSTRACT The management of heart failure (HF) and atrial fibrillation (AF) in real-world practice remains a debating issue,while the number of HF patients with AF increase dramatically. While it is unclear if rhythm or rate control therapy is more beneficial and under which circumstances, anticoagulation therapy is the cornerstone of the AF-HF patients’ approach. Vitamin-K antagonists were the gold-standard during the past, but currently their usage is limited in specific conditions. Non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants (NOACs) have gained ground during the last ten years and considered as gold-standard of a wide spectrum of HF phenotypes. The current manuscript aims to review the current literature regarding the indications and the optimal choice and usage of NOACs in HF patients with AF.

The progress of basic and clinical research has resulted in the better understanding of the underlying mechanisms of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and the growth of novel pharmacotherapies. Therefore, an increased longevity and a reduced cardiovascular (CV) mortality characterize heart failure (HF) patients nowadays.However, there is still room for improvement, especially in the heart diseases management. HF and atrial fibrillation (AF) constitute two of the many faces of “Lernaean Hydra” called CVD and they regularly accompany each other.[1]A bidirectional correlation and not a cause-effect relationship seems to exist between the two diseases.[2]Undoubtedly,the presence of both AF and HF worsen the disease evolution of these patients, while HF severity consists a primary prognostic factor.[3]Patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) stage III or IV are more prone to develop systematic embolization,stroke or major bleeding.[4]

The management of HF-AF remains challenging,as it requires comprehensive physical examination,clinical symptoms’ evaluation and comorbidities’thorough assessment. Pharmaceutical treatment is based on the following triptych: stabilization of the substrate-main disease, rhythm- or rate-control and anticoagulation therapy. While it remains debating,if rhythm- or-rate-control therapy is more beneficial and under which circumstances, anticoagulation therapy is the cornerstone of the HF-AF patients approach, preventing the further devastating complications such as stroke and disability.[5]Anticoagulation therapy includes mostly vitamin-K antagonists (VKAs) and non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants (NOACs).[6]Antiplatelet drugs were used extensively for low-risk patients in the past, but the modern data do not support their administration.[7]

The current manuscript aims to specify patients requiring anticoagulation, to choose the optimal medical treatment and to provide guidance for the special subgroups.

SELECTION OF PATIENTS REQUIRING ANTICOAGULATION

Patients with AF have a significantly increased risk for thromboembolism, as the irregular heart rhythm promotes thrombus’ creation in left atrial appendage (LAA), detachment and embolization in either systemic or cerebral circulation. Meanwhile,HF stands as an independent thrombosis factor, irrespectively of the left ventricular function.[8]Thus,these patients need optimal management of anticoagulation therapy, to reduce thrombotic risk. For this purpose, CHA2DS2-VASc score has been developed and currently used, as an evolution of CHA2DS score.[9]When CHA2DS2-VASc is ≥ 1 in men and ≥ 2 in women, anticoagulation treatment is recommended with a level of evidence IIa.[7]Regarding CHA2DS2-VASc score, “C” stands for the congestive HF, referring to at least moderate LV dysfunction during cardiac imaging or a new episode of decompensated HF, independently of the EF. Nowadays, HFpEF displays a partially understandable pathophysiology with multi components. Notably, HFpEF-AF patients require generally anticoagulation therapy,as these patients present numerous comorbidities,like hypertension (HTN) or diabetes mellitus (DM),which are factors further contributing to high CHA2DS2-VASc score evaluation.

In summary, most of patients with HF-AF require anticoagulation therapy, but the choice of optimal anticoagulation drug requires more consideration, according to the individualized bleeding risk of each patient. The balancing between hemorrhage and thrombosis remains a sensitive issue, which must always be taken into consideration.[10]Similar to CHA2DS2-VASc score, several scores have been proposed for predicting the bleeding risk, such as HAS-BLED score, that is widely used.[11]Patients with HF-AF usually share additional systemic diseases, which lead to the increase of HAS-BLED score and the bleeding risk respectively.[12]Patients with both these scores increased are frequently encountered in daily clinical practice and require a tailored approach, in order to prevent a fatal thrombotic or bleeding episode.

Vitamin-K Antagonists

The previous decades, VKAs were the first line agents for thrombogenesis and embolization prevention, saving millions of patients. They have been associated with 65% reduction of ischemic strokes,decreasing the absolute risk about 2.7% and 8.4%for primary and secondary strokes prevention in patients with non-valvular AF.[13]VKAs have been proven superior against single (aspirin) or dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin with clopidogrel) for thrombosis prevention in AF patients.[14]VKAs are still the gold standard for HF patients with mechanical valves, for those with at least moderate mitral valve stenosis and those suffering from antiphospholipid syndrome.[15]VKAs demonstrate several issues further eliminating their prescription in realworld practice. Foremost, International Normalized Ratio (INR) must be estimated frequently in patients under VKA, as the target therapeutic range is narrow, meaning that the balance between bleeding and thrombosis is really challenging. Moreover,patients with HF-AF are often under multiple pharmacotherapies, while the drug-drug interactions affect the VKAs metabolism and pharmacokinetics,reducing their efficacy.[16]Dietary habits could be another issue as they are related with further instability and risk of sub-therapeutic INR values.[17]In addition, HF, via liver congestion, can lower the metabolism of VKA, increasing the INR and the bleeding risk. However, it remains unclear if VKAs’therapeutic range is affected by the existence of HF.[18,19]Nevertheless, the frequent episodes of severe HF decompensation may also affect the metabolism, the safety and the efficacy of VKAs.[20]

Non-Vitamin K Oral Anticoagulants

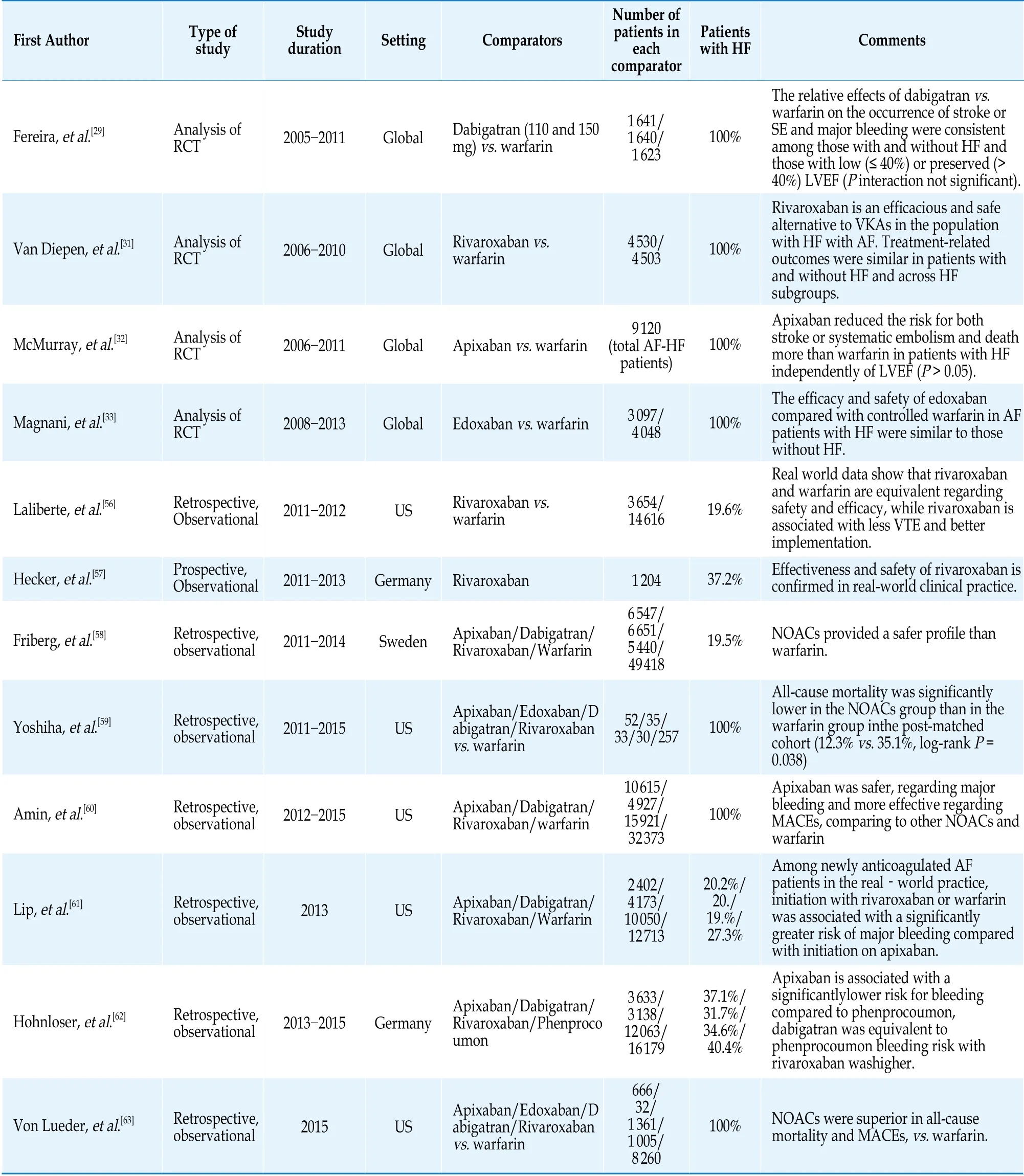

The development of the NOACs has substituted VKAs’ clinical usage. NOACs’ approval and application in everyday clinical practice was a revolution for the modern cardiovascular medicine and a precious pharmaceutical weapon against thromboembolism. Currently, there are four NOACs approved by FDA; dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban. The recent guidelines for AF published by European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recommend the administration of NOACs for stroke prevention in non-valvular AF with an evidence of Ia.[7,21]Rivaroxaban, apixaban and edoxaban share a mutual mechanism of action, by inhibiting the factor Xa. Dabigatran acts in a different level of coagulation cascade, by antagonizing directly the thrombin (coagulation factor II).[22]All of the NOACs have been previously compared with warfarin by randomized control trials, conducted in non-valvular AF population, with a significant proportion of HF.[23-26]Prior of these studies, AVERROES was the first trial evaluating apixaban versus aspirin, showing a clear benefit in favor of apixaban regarding the reduction of strokes and systemic embolization without any attenuation of its safety profile, driving to early termination of the trial.[27]Table 1 reviews the major studies assessing safety and effectiveness profile of NOACs, including both randomized-control trials and observational studies,focusing on HF-AF subpopulation.

Ximelgatran (direct thrombin inhibitor) set the stage for NOACs, being approved in 2004 but was withdrawn in 2006 due to significant liver toxicity.[28]Dabigatran was the first NOAC approved, released and used until today. RE-LY trial documented the safety and efficacy of dabigatran regarding the bleeding risk and stroke prevention compared to warfarin.[24]RE-LY was a prospective, randomized,open-label with blinded endpoint evaluation trial,conducted in about 18,000 with a three-years duration. The patients were randomized between warfarin or one of two doses of dabigatran (110 mg or 150 mg, twice a day). RE-LY demonstrated that the high-dose regimen was associated with significantly lower stroke risk but equal bleeding risk, compared to warfarin. The lower dabigatran dose was not inferior to warfarin, regarding the stroke risk,demonstrating a significantly lower bleeding risk.RE-LY trial included 4 904 patients with HFrEF and the subgroup analysis showed reduced ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic risk for HF patients under dabigatran, irrespectively the dose.[29]Dabigatran is mainly excreted through kidneys via urine. Thus,kidney function should be evaluated regularly, and its administration should be avoided in patients with renal impairment and creatinine clearance(CrCL) < 30 mL/min. An important drawback regarding anticoagulation therapy could be a major bleeding. Recently, idarucizumab-an antidote for dabigatran-has been approved and nowadays its use is widespread facilitating the management of bleeding complications from dabigatran.[30]

Rivaroxaban was the second NOAC released in the United States, while it was the first NOAC inhibiting factor Xa. It achieves a bioavailability greater than 80% and has a combined, hepatic and renal,clearance. ROCKET-AF was a randomized-control,double-blinded trial, comparing the administration of 20 mg or 15 mg rivaroxaban in patients with CrCL lower than 50 mL/min versus the warfarin prescription, targeting to a control INR between 2-3.[23]Rivaroxaban was considered as non-inferior to warfarin regarding the cerebral and systemic embolization while the severe and fatal bleeds were comparable between the two arms, except gastrointestinal bleeding whereas rivaroxaban’s incidence was statistically more significant. However, warfarin was associated with more intracranial and fatal bleedings, comparing to rivaroxaban. ROCKET-AF included a significant proportion of HF patients(9,033 patients, 63.7% of the total sample) and HF was defined either as clinical entity either or with an EF lower of 35%. The subgroup analysis of HFpatients participated in ROCKET-AF confirmed that the results of main study can be applied in HF-subgroup. More specifically, the rate for systemic embolization or stroke was similar in both groups (1.90vs. 2.09 per 100 patients-years), as well as the risk for major bleeding (14.22vs. 14.02 per 100 patientsyears). Rivaroxaban seems to reduce hemorrhagic stroke risk in HF patients.[31]Renal dysfunction should be evaluated, when it exists. Patients with CrCl > 50 mL/min could be treated with 20 mg rivaroxaban, while those with CrCl < 15 mL/min should not be treated with the specific drug. A CrCl between 16 and 49 mL/min is the “gray” zone.Evidence supports that a 15 mg dose should be administered in such patients, while others recommend more conservatively that the “cut-off” for rivaroxaban should be placed in CrCl 30 mL/min.

Apixaban is another NOAC, which inhibits Xa factor. With a similar mechanism of action like rivaroxaban, apixaban was shown superior to warfarin in preventing cerebral or systemic embolization, in bleeding and in mortality.[25]This was proven by ARISTOTLE trial which enrolled 18,201 patients, that further were randomized in two arms;placebo (warfarin) and intervention, apixaban 5 mg or 2.5 mg (twice a day) in selected subjects. The dose selection was according to the age, the weight and the creatinine levels of patients. Likewise, the previous NOACs’ trial, the subgroup analysis of ARISTOTLE interpreted the superiority of apixaban to warfarin in patients with left ventricle systolic dysfunction.[32]This analysis included 2 736 patientswith reduced ejection fraction and 3 207 with preserved EF. Death, major bleeding and systemic embolization were less frequent in patients treated with apixaban compared with those under warfarin,further expanding the indications for apixaban into HF population.

Table 1 Selected studies, including AF-HF, comparing NOACs vs. warfarin.

Edoxaban is the “last but not least” NOAC approved by FDA and released worldwide. ENGAGEAF-TIMI 48 trial was a double-blind, randomizedcontrolled trial, which proved the safety and efficacy of edoxaban.[26]Except the placebo arm with warfarin, there were two more arms; the first with patients treated with high-dose (60 mg) edoxaban while the second with low-dose (30 mg). Independently of the treating dose, edoxaban was non-inferior to warfarin regarding the efficacy, while it was associated with lower annual bleeding risk and major cardiovascular outcomes. A 57.9% of total patients of ENGAGE-AF-TIMI 48, namely 8 145 patients,were diagnosed with HF. The specific subgroup analysis showed that edoxaban remains effective and safe for HF patients, irrespectively of the underlying EF.[33]Unfortunately, edoxaban requires careful prescription, especially in patients with renal impairment and monitoring for any weight gain.It is noteworthy that edoxaban displays a significant (50%) renal clearance and patients with creatinine clearance (CrCl) < 30 mL/min, were excluded from ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48. Furthermore, patients with moderate renal dysfunction (CrCl = 30-50 mL/min)and low body weight or concurrent use of a potent phosphorylated glycoprotein inhibitor received a 50% lower dose.

A metanalysis by Xiong,et al.[34]showed that among AF-HF patients, mostly a single or high-dose NOAC regimen had a better efficacy and safety profile, but a low-dose regimen revealed similar efficacy and safety to VKAs. NOACs were equally effective or even superior especially for intracranial hemorrhage,in AF-HF patients compared with those without HF. HF patients from the previous major trials were included.[29,31-33]The risk for stroke or systemic embolization was reduced by 14% (odds ratio = 0.86,95% confidence interval (CI): 0.76-0.98) and for major bleeding by 24% (odds ratio = 0.76, 95% CI:0.67-0.86), when the patients were treated with single or high-dose NOAC regimen. Regarding the low-dose regimen, efficacy was comparable between NOAC and warfarin and a non-significant trend for lower major hemorrhage was noticed. Another meta-analysis investigating the same population concluded that patients with HF-AF had reduced rate for any bleeding risk, while elevated risk for all-cause mortality.[35]The authors highlighted that NOACs were superior to warfarin in any comparison; stroke or systemic embolization, major bleeding and intracranial hemorrhage.[35]The NYHA status of patients did not change the main findings, confirming that NOACs remain a safe and effective solution even in critical HF patients.

Individualization of NOAC therapy

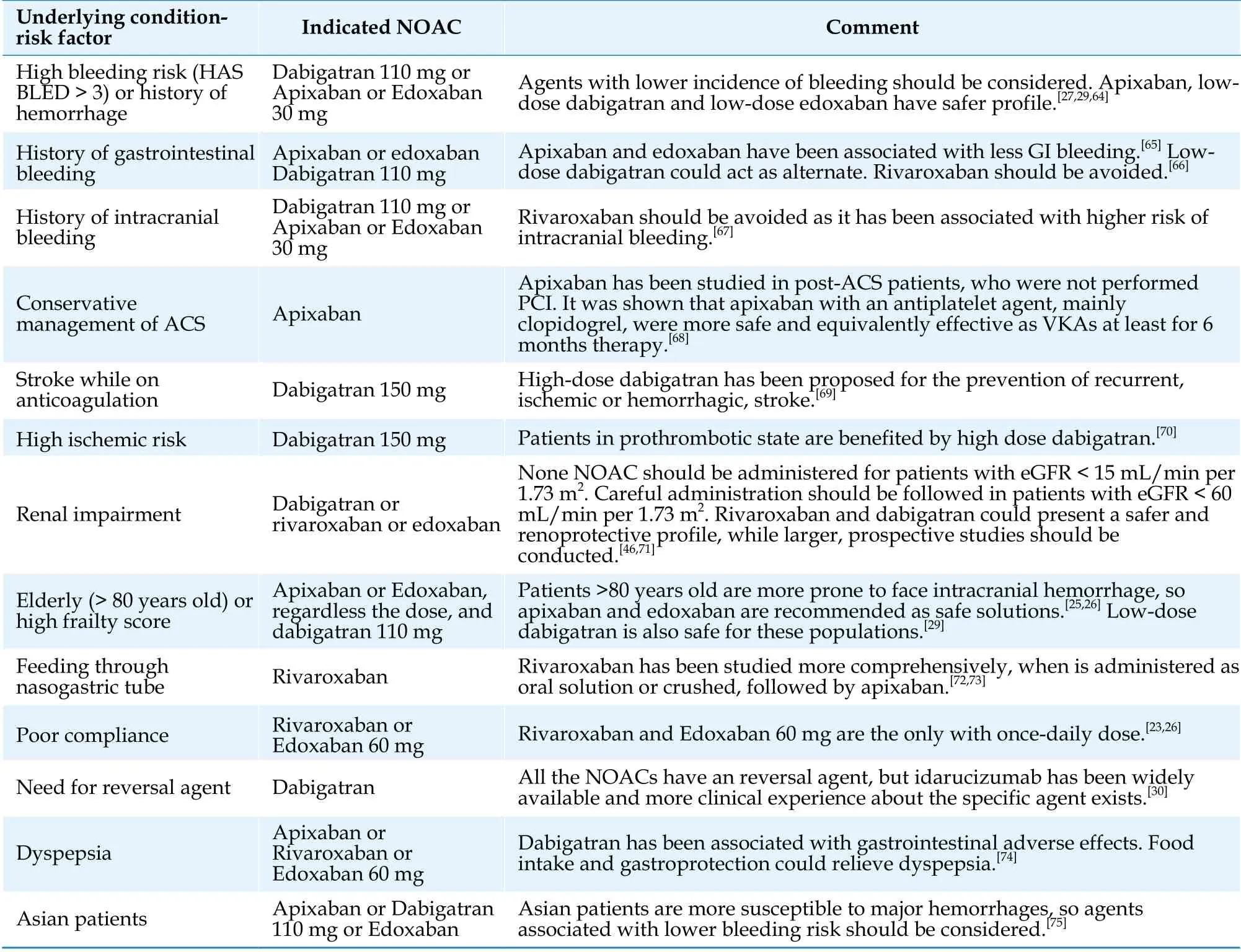

While the indications for NOACs versus VKAs concerning non valvular AF patients have been documented clearly, the selection of the suitable NOAC remain an unanswered question. Existing guidelines are inadequate for the specific purpose and a more personalized approach, based on each patients’ comorbidities and characteristics, should be applied.To the best of our knowledge, no pharmaceutical agent has gained ground for the patients with HFAF. A recent network meta-analysis showed that apixaban, dabigatran of 150 mg and edoxaban of 60 mg should be preferable for providing better combined safety and efficacy, but more evidence is required.[36]Table 2 reviews current implications and trends about the selection of appropriate NOAC,based on the underlying pathological substrate. While they are not specialized on AF-HF, such recommendations can be applied in the specific subgroup.

ISSUES REGARDING SPECIAL POPULATIONS

AF-HF patients consist a heterogenous group,with many differences regarding underlying pathophysiology, clinical manifestations and management. As a result, tailoring of treatment is mandatory in specific subpopulations. Therefore, we will analyze the issues arising in the treatment of post-TAVI and renal failure patients. LAA occlusion seems to be the final step regarding ischemic events prevention for patients with high bleeding and ischemic risk.

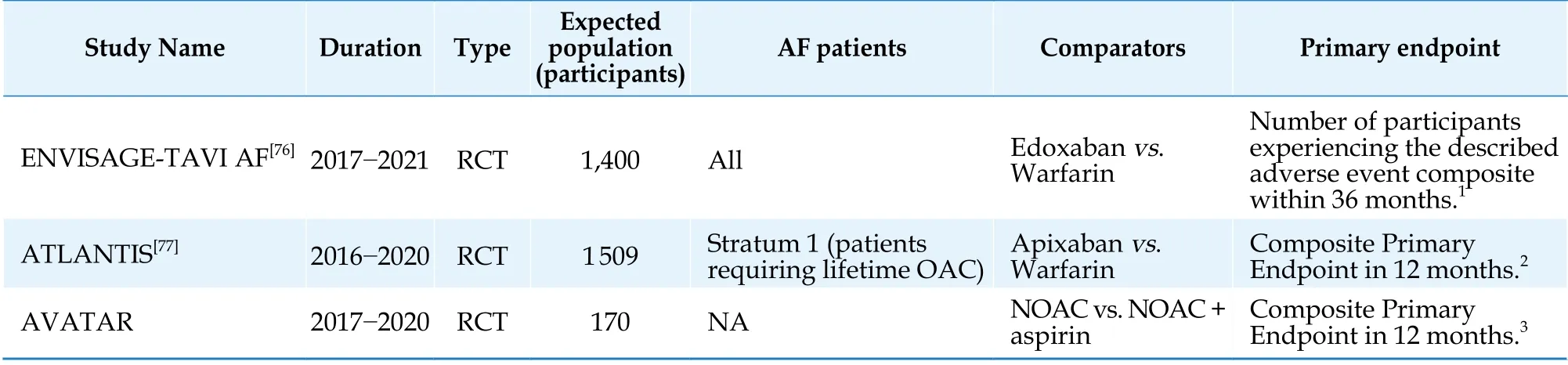

TAVI in AF-HF Patients

The development of interventional cardiology has resulted in the improvement of prognosis and longevity of patients with severe aortic valve stenosis (AoS). However, these patients may frequentlyhave HF-AF and require individualized treatment,especially after transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI).[37,38]Optimal treatment regarding post-TAVI patients with HF does not exist.[39]Nevertheless, limited literature has been published regarding this issue and more research is required for the better treatment of post-TAVI patients with HF and AF. Nowadays, there are three ongoing trials studying the specific subject and they will include patients with HF (Table 3).

Table 2 Recommendations about the selection of right NOAC, regarding the underlying pathology or risk factor.

Anticoagulation therapy in HF patients with renal failure: a vicious cycle

Renal function of AF-HF patients under anticoagulation remains fragile and needs special care.Both HF and anticoagulation may negatively affect the kidney function. HF is characterized by low cardiac output and low organ perfusion.[40]The maintaining hypoperfusion of kidneys causes chronic ischemia, inducing significant structural and functional renal abnormalities.[41,42]In the meanwhile,the protracted anticoagulation therapy is also associated with renal impairment which could be triggered by glomerular hemorrhage.[43,44]Both NOACs and VKAs have been charged for worsening renal function, but NOACs may provide a better safety profile.[45]Dabigatran and rivaroxaban have been connected with lower risk for developing renal adverse outcomes, but more prospective,randomized trials should be conducted in this direction.[46]Nonetheless, kidney injury caused by anticoagulation treatment consists a major reason for therapy discontinuation.[47]In summary, renal function of this subgroup of patients is affected fromboth the disease and the therapy, so a personalized and cautious approach is mandatory.

Table 3 Ongoing trials studying the anticoagulation treatment in patients with AF and HF, who underwent TAVI.

LAA Occlusion for Patients with High Bleeding and Ischemic Risk

Balancing especially between high bleeding and ischemic risk remains a challenging issue in patients with HF-AF and several additional comorbidities. More specifically, LAA ejection velocity is reduced in HF-AF patients, promoting blood stasis and thrombus’ creation.[48]These patients probably demonstrate increased both bleeding and ischemic risk scores and there was no optimal treatment until recently. Thanks to interventional cardiology progress, transcatheter LAA occlusion is a feasible and safe option.[49,50]By the percutaneous implantation of suitable device in LAA, thrombus’ development is prevented and embolization risk is reduced.[51,52]LAA occlusion in HF patients has been studied in separate studies as well as subgroup analysis in larger studies, showing promising results.[53-55]

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the coexistence of AF in HF patients will be expected to increase in the future. The management of these patients requires a comprehensive, multi-approach evaluation for an optimal result, while the role of anticoagulants in medical therapy remain fundamental. The progress of pharmacology has provided us with NOACs, consisting a valuable weapon against HF-AF. Their safety and efficacy have been proven via multiple studies,while the VKAs’ administration in everyday clinical practice has been limited on specific indications.More research is required for tailoring the anticoagulation treatment in special subgroups of HF-AF patients.

杂志排行

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology的其它文章

- Atrial fibrillation in patients with systolic heart failure:pathophysiology mechanisms and management

- Beta-blocker treatment in heart failure patients with atrial fibrillation: challenges and perspectives

- A case series of precipitous cardiac tamponade from suspected perimyocarditis in COVID-19 patients

- A valve-in-valve approach to manage severe bioprosthetic tricuspid valve stenosis

- Coronary artery disease presenting as intractable hiccups: an unclear mechanism

- Cardiac papillary fibroelastoma