Liver transplantation for liver failure in kidney transplantation recipients with hepatitis B virus infection

2021-03-05PengPengZhngXingGuoSheKeChengHongLiuYingNiuYingZiMing

Peng-Peng Zhng , , Xing-Guo She , , Ke Cheng , , Hong Liu , , Ying Niu , ,Ying-Zi Ming , ,

a Transplantation Center, Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410013, China

b Engineering & Technology Research Center for Transplantation Medicine of National Ministry of Health, Changsha 410013, China

TotheEditor:

Worldwide, approximately 400 million patients have chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection [1]. Because of the high incidence of HBV in China, the incidence of HBV infection in uremia and kidney transplantation (KTx) patients is 2.5% and 2.7%,respectively [2]. Since the first successful organ transplant conducted between twins in 1954, refined surgical techniques, improved immunosuppressive protocols, and improved perioperative management of transplant patients have resulted in improved patient and graft survivals following K Tx [3]. However, the K Tx community is now challenged with liver failure due to the increased risk of HBV viral activation and replication induced by immunosuppressive therapy. Harnett et al. [4]highlighted that KTx recipients with HBV infection had lower 5-year survival (61%) than patients on dialysis (85%). Although these KTx recipients were treated with regular anti-HBV therapy, the incidence of liver failure was increased in KTx patients with HBV infection. Currently, isolated liver transplantation (LTx), sequential liver and kidney transplantation (SLKT), and combined liver and kidney transplantation (CLKT)are the optimal treatments for patients with liver failure and hepatorenal syndrome [5]. However, the outcomes of KTx recipients following isolated LTx, SLKT or CLKT for HBV-associated liver failure remain to be studied. Herein, we report our experience in ten HBV-positive KTx recipients with liver failure undergoing LTx.

Ten KTx recipients who underwent isolated LTx (n= 6), SLKT(n= 2) or CLKT (n= 2) for HBV-associated liver failure were retrospectively reviewed in our institution between 2014 and 2019. The clinical and laboratory data and outcomes were collected. The data included patient age, sex, body mass index (BMI), date of KTx, date of LTx, type of LTx, the use of dialysis before LTx, creatinine levels pre- and post-LTx, the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD)score, HBV-DNA level, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)before LTx, hemoglobin and albumin level before LTx, immunosuppressive regimens after LTx, patient outcomes and cause of death.Written informed consent was obtained from patients who participated in this study. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University(No. 2020-S024). The study protocol was designed and conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines and regulations of theDeclarationofHelsinki.

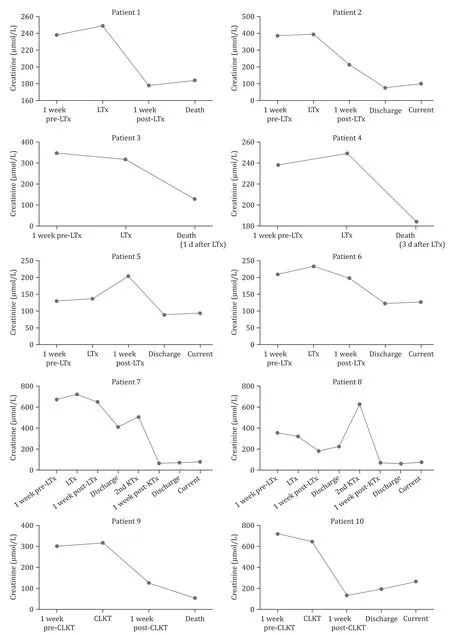

From 2014 to 2019, ten KTx recipients, including six men and four women, underwent isolated LTx, SLK T or CLK T in our institution. The indications for LTx were HBV-associated liver failure.The demographic and clinical data are summarized in Table 1 , and the laboratory data are summarized in Table 2 . The median time from the first KTx to liver failure was 5.4 years. The median age of ten patients was 47 years, and the median BMI was 17.9 kg/m2. Six patients suffered from HBV flare-up, with HBV-DNA levels greater than 10 IU/mL, and the other patients were HBV chronic carriers. The median eGFR before the LTx was 15.7 mL/min/1.73 m2.The median creatinine before and after LTx were 345 μmol/L and 106 μmol/L, respectively; the serial changes in renal function before and after LTx are shown in Fig. 1 , revealing that the renal function of these patients improved after LTx. The median hemoglobin and albumin levels pre-LTx were 69 g/L and 27.9 g/L, respectively.The median MELD score was 22 before LTx. Six out of ten patients underwent an isolated LTx, two patients underwent a CLKT, and two patients underwent an SLK T, with the 2nd K Tx performed six months and one year and a half after LTx, respectively.

All the transplant recipients received tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisolone as their immunosuppressive regimens. Six of ten patients were already receiving regular or intermittent hemodialysis as renal replacement therapy before LTx;these patients recovered except for one death. Two patients died after surgery due to pneumonia and septic shock, one patient died of primary nonfunction (PNF), and one patient died of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), respectively.

The demographic and clinical data of ten patients showed some similar characteristics and manifestations: i) poor renal allograft function and nutritional status: liver failure was easily combined with hepatorenal syndrome, which manifested as high creatinine levels, anorexia and hypoalbuminemia and affected nutritional intake; ii) poor immune function: the patients had reduced immune function due to the long-term use of immunosuppressive drugs,and some patients had underlying infections, including pneumonia and peritonitis; and iii) more complications and higher mortality:poor liver function, poor renal function, and infections resulted in increased complications and mortality.

Fig. 1. Serial changes in renal function pre- and post-LTx and/or at the 2nd KTx. The renal function of all patients improved after surgery. LTx: liver transplantation; KTx:kidney transplantation; CLKT: combined liver and kidney transplantation.

e.lur fai ver li ed iat soc as HBV-th wi s ient pat KTx ten of a dat al ic in cl and ic aph 1 e demogr Tabl The h deat MODS:of on on on;e ti ti ti Caus ec Inf ec unc–PNF MODS––––Inf–nonf dy of d ddd(90 imar come(17 y yy LTx)(1 yy(3 y(30 pr LTx)h ient over LTx)h LTx)h LTx)Out over h over over over over pat Deat ter ter ter ter ter PNF:af Rec Deat af Deat af Rec Rec Rec Rec Deat af Rec af;rus vi LTx B e-is it HBV pr rrrrrrrrrr avi apy ovi avi ovi ovi avi ovi avi avi avi i-hepat Ant ther ec Ent ec Ent Tenof Tenof Tenof ec Ent Tenof ec Ent ec Ent ec Ent:HBV sant ion;es ed at ed LTx ed+ Pr ed ed+ Pr ed+ Pr ed+ Pr+ Pr ed+ Pr t-uppr ant ed+ Pr+ Pr ed+ Pr+ Pr pl Immunos pos and ans tr e-+ MMF+ MMF+ MMF+ MMF+ MMF+ MMF+ MMF+ MMF+ MMF+ MMF pr Tac Tac Tac Tac Tac Tac Tac Tac Tac Tac dney ki and e dat ver li KTx 2019 2019 2014 2015 ned 2nd 31/29/3/8/– – – – ––5/5/10/1/combi KT:LTx LTx LTx LTx LTx LTx CL.type ed ion;one at ed at ed at ed at ed at ed at at ol LTx ol ol ol ol ol ol KT KT KT KT is Is Is Is Is Is Is SL SL CL CL ant pl ans edn pr e ed:2014 2017 2014 2014 2017 2017 2017 2018 2014 tr dat 29/24/29/Pr 2015 dney 10/;LTx 11/18/15/10/26/10/10/3/ki 8/6/6/4/6/10/8/1/and imus ver rol tac LTx li:2012 2009 ial e-Tac;pr il e 2002 2004 22/et dat 8/29/4/2011 2016 sequent 6/7/6/10/2006 2010 2014 2011 2007 2005 KTx 22/1/21/tt e mof 1s 2nd 1s 2nd 8/8/4/18/7/3/3/11/11/5/12/5/4/KT:SL at is is ion;LTx ys ys is is is is at ophenol e-al al ys ys ys ys ant pr di di al di di al di al al di pl is lar lar ys lar lar lar lar ans tr al MMF: myc Di No regu regu Ir No No No Ir Regu Regu Regu Regu dney ki ome;e eee e eeeee syndr Sex Mal Femal Mal Mal Mal Mal Femal Femal Femal Mal KTx:ion;on ti)at(yr ant func Age pl dys 65 24 57 48 46 61 39 29 44 59 ans tr gan or ient ver le li ip Pat lt 1234567891 0 LTx:mu

)/L(μmol LTx t-pos Cr 184 76 129 177 89 123 71 61 31 194)/L(μmol LTx e-pr Cr 238 387 349 341 130 209 675 356 302 715.rus vi 2 )B m is 73 it 1.in/hepat/m:(mL HBV LTx e;e-seas pr di eGFR.7.3.8.3.4.6.2.5 ver 23 15 15 17 56 28 1 6.14 15 6 6.li age)st mL U/end-(I for LTx e-pr DNA 3574102 D: model HBV-8 ×10 10 10 10 10 1.9 ×10 3.9 ×10 9 ×10 1 ×10 8 ×10<<<7.3.<4.1.index; MEL L)s(g/LTx mas e-pr body I:b.1.5.1.3.5.9.7.9.8 BM e.Al 27 28 25 27 27 30 28 34 30 26 lur in;fai L)ver(g/bum al li LTx b:ed e-Al iat pr n;soc Hb 63 76 65 57 73 64 91 83 47 82 obi as HBVLTx hemogl th e-wi pr Hb:e s ient or sc ine;in pat D eat KTx MEL 19 24 35 32 21 19 20 23 18 23 cr:Cr ten 2 )of m ion;at a dat(kg/ant I.6.9.3.3.1.5.4.6.2.8 pl y or BM 17 17 19 19 21 19 17 17 17 17 ans at tr 2 ver e labor ient li Tabl The Pat 1234567891 0 LTx:

Over the years there have been numerous advances that have led to improved outcomes and quality of graft and life for KTx patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). However, the kidney transplant community with HBV infection is now challenged with liver failure because these patients have a high risk of HBV viral activation and replication induced by immunosuppressive regimens or nonadherence to anti-HBV agents. In our institution, the prevalence of liver failure among the KTx recipients with chronic HBV infection was 2.86% and the frequency of LTx among these KTx recipients with chronic HBV infection was 1.33%. To the best of our knowledge, this experience in ten HBV-positive KTx recipients with liver failure undergoing LTx represents the largest series reported to date.

In the present study, six of ten patients underwent isolated LTx. The patient outcomes in this group indicated that although the allograft function of the KTx recipients was affected by liver dysfunction, most patients improved after isolated LTx. Even if some of them required hemodialysis to maintain homeostasis after surgery, a second KTx could be performed. In our institution, two patients underwent SLKT, and both recovered without postoperative infection. Two patients underwent CLKT. However, one patient died of pneumonia and septic shock 30 days later with normal renal and liver function. Another patient developed a pulmonary fungal infection and recovered with azotemia three months later.CLKT is now a well-established therapeutic approach for patients with irreversibly impaired renal and liver function, and the indication for CLKT was end-stage liver disease (ESLD) with an eGFR of 30 mL/min/1.73 m2or less [6], but CLKT seemed to be unsuitable for this group of patients because of the high infection rate.From the study results, the eGFR of these patients was less than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, but the outcomes of the allograft and the patients after an isolated LTx or SLKT were better than the outcomes following CLKT. We thought that physically, KTx recipients with HBV infection, who had poor nutritional status and renal function,were too weak to bear the surgical stress of CLKT. Therefore, isolated LTx and SLKT, which had a lower surgical burden and could reduce the incidence of infection, were the optimal surgical options, at least in our institution.

The use of hemodialysis as renal replacement therapy may aggravate the negative nitrogen balance and nutrient consumption,resulting in more transplantation complications and increased patient mortality [7]. In the present study, one patient died of MODS after surgery, which may have resulted from a long transplant waiting time. Therefore, early surgery could reduce mortality, and the pre-dialysis stage was the best chance for surgery.

The median MELD scores of our patients were high. Recent evolving trends for CLKT following MELD implementation suggest that grafts may be preferentially allocated to critically ill recipients who may not benefit from such a practice because of their advanced disease stage [8]. Due to the poor physical status of these patients, they had increased mortality, which sometimes could lead to organ waste. New allocation criteria, which are not based on MELD scores, are required for this group of patients, to avoid organ waste in the future.

Donor selection is an important factor for graft and patient survival. In this study, one patient died from liver PNF, which was due to a transplant from a marginal donor. Therefore, high-quality donors are crucial to avoiding liver PNF and delayed graft function in this group. Additionally, high-quality donors can promote the recovery of renal function and may improve the patients’ nutritional status.

Reactivation of HBV, because of the immunosuppressive drugs or nonadherence, could result in the rapid deterioration of liver function and might increase mortality [9]. Anti-HBV therapy including the use of anti-HBV immunoglobulin and antiviral agents during the perioperative and postoperative period was important for these patients. At our center, we used anti-HBV immunoglobulin (40 0 0 IU) during anhepatic phase and administered oral anti-HBV agents after the operation (if the patient used entecavir pre-LTx, tenofovir was used instead, and vice versa) for these LTx patients. Moreover, we recommend that the patients be checked for HBV-DNA every three to six months during follow-up examinations to guide antiviral treatment.

In the present study, two patients died from pneumonia,which supported the importance of infection control after surgery.However, the symptoms of infection in the transplant recipients were not typical because of the long-term use of immunosuppressive drugs, which might easily mask the diagnosis of infection. Currently, next-generation sequencing (NGS) is a technology that could potentially replace many traditional microbiological methods, providing clinicians with more actionable and practical information [10]. NGS is being used in many other clinical fields,such as stem cell transplant [11]. For transplant patients, specific therapies identified by NGS may reduce the incidence of secondary opportunistic infection. Patient nutritional support should be improved during the perioperative period to reduce the incidence of infection and patient mortality.

Despite vaccination programs worldwide, HBV infection is still one of the biggest public health challenges in China [12]. Although LTx and KTx have become the optimal treatments for ESLD and ESRD, respectively, patients receiving LTx and KTx are threatened by HBV infection. Therefore, more attention should be paid to regular anti-HBV therapy to enhance adherence and to optimize the immunosuppressive regimen for KTx recipients with HBV infection.It is also necessary to regularly measure liver and renal function and perform HBV virologic testing to avoid the occurrence of liver cirrhosis and organ failure to improve patient survival and quality of life.

In conclusion, this single-center study showed that the isolated LTx and SLKT patients had a lower infection rate than patients with CLKT.

Acknowledgments

We thank professor Shu-Sen Zheng for helpful advice on the management and treatment of the patients included in this study,and professor George B Stefano and Richard M Kream for helping to review and revise the manuscript.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Peng-Peng Zhang:Data curation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.Xing-Guo She:Data curation, Resources.Ke Cheng:Project administration, Formal analysis.Hong Liu:Data curation.Ying Niu:Methodology, Software, Supervision.Ying-Zi Ming:Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing- review & editing.

Funding

The study was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81771722).

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (No. 2020-S024).

Competing interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- BCLC staging system and liver transplantation: From a stage to a therapeutic hierarchy

- Multidisciplinary management of patients with post-inflammatory pancreatic necrosis

- Abdominal drainage systems in modified piggyback orthotopic liver transplantation

- Transjugular portosystemic shunt for early-onset refractory ascites after liver transplantation

- Giant pseudoaneurysm of the splenic artery within walled of pancreatic necrosis on the grounds of chronic pancreatitis

- Hepatic isolated ectopic adrenocortical adenoma mimicking metastatic liver tumor