社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系:一项元分析*

2021-03-04张亚利俞国良

张亚利 李 森 俞国良

社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系:一项元分析

张亚利李 森俞国良

(中国人民大学教育学院;中国人民大学心理研究所, 北京 100872)

社交媒体使用与错失焦虑均是当下生活中较为常见的现象, 诸多研究探讨了两者间的内在联系, 但研究结果却存在很大差异。为明确两者之间的整体关系, 以及产生分歧的原因, 对检索后获得的65项研究(70个独立样本)使用随机效应模型进行了元分析。结果发现:社交媒体使用与错失焦虑存在显著正相关(= 0.38, 95% CI [0.34, 0.41]); 二者的相关强度受社交媒体使用测量指标和社交媒体类型的调节, 但不受性别、年龄、错失焦虑测量工具和个体主义指数的调节。结果一定程度上澄清了大众传播的社会认知理论和数字恰到好处假说的争论, 表明社交媒体使用程度越高的人往往也会伴随着较高水平的错失焦虑。防止社交媒体过度使用, 尤其是引导大众合理使用以图像为中心并且开放度较高的社交媒体有助于错失焦虑的缓解。

错失焦虑(错失恐惧), 社交媒体, 社交网站, 元分析

1 引言

随着无线互联网技术的发展和移动设备的不断升级, 众多社交媒体也应运而生并逐渐融入到人们的生活中, 近年来不断受到大众的追捧。据调查显示, 中国仅微信朋友圈的使用率就达到了85.1% (中国互联网络信息中心, 2020)。社交媒体不仅为人们建立和拓展社会关系提供了极大的便利, 也为人们了解外界信息提供了重要窗口(Dempsey et al., 2019; 张亚利等, 2020)。然而, 人们在使用社交媒体的过程中, 有一定比例的人群出现了问题性使用现象, 给心理健康带来潜在威胁(Rasmussen et al., 2020)。如有研究发现, 频繁使用社交媒体的青少年出现重度抑郁和自杀行为的风险会更高(Twenge et al., 2018)。随着研究视角的拓展, 近来研究者又将着眼点聚焦于社交媒体使用的又一负面效应上, 认为社交媒体使用可能会诱发错失焦虑(Brown & Kuss, 2020; Buglass et al., 2017; Hunt et al., 2018)。错失焦虑(Fear of Missing Out, FoMO)在社交媒体盛行的当下表现的日益普遍, 研究显示, 有66%的人曾经历过这种焦虑, 并且在每天较晚及周末的时候最为严重(Huguenel, 2017; Milyavskaya et al., 2018)。因此, 两者间的内在联系成为了当下众多研究关注的焦点, 然而其得出的结论却并不一致。有研究发现两者可能存在显著的正相关(Baltaet al., 2020; Tunc-Aksan & Akbay, 2019), 而另外一些研究却发现两者相关不显著(Franchinaet al., 2018; Gezgin, 2018)。此外, 两者的相关程度在既有研究中亦存在较大差异,值从0到0.75均有报告(Franchina et al., 2018; 李静, 2020; Ponteset al., 2018)。因此, 社交媒体使用与错失焦虑有无相关, 相关程度几何, 成为了亟待解决的问题。为解决该领域的争议, 从宏观角度得出更普遍、更精确的结论。本研究拟采用元分析的方法, 通过探讨社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的总体相关性和可能的调节因素, 为社交媒体使用的深入研究和合理引导提供更多的证据支持, 以便更好的趋利避害。

1.1 社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的概念和测量

社交媒体是指允许用户创建、分享和交流信息的在线平台, 搭载的内容包括文本、图像、音频和视频(Mieczkowski et al., 2020; Rozgonjuk et al., 2020)。国外常用的社交媒体有Facebook, Instagram及Snapchat等(Wegmann et al., 2017), 国内常用的有微信、微博及QQ等(中国互联网络信息中心, 2020)。社交媒体使用则是基于社交媒体开展的各种活动的总称, 研究者从使用频率、使用时间、使用强度及使用成瘾等角度对其进行了测量, 均能衡量社交媒体的使用程度(Mieczkowski et al., 2020)。使用频率主要测量各个社交媒体或社交功能的日常使用频率, 如点赞、转发的次数, 代表性的工具有Rogers和Barber (2019)编制的社交媒体使用量表, 共包括5个题目。使用时间主要测量社交媒体每日或每周使用的时长, 代表性的工具有Buglass等(2017)编制的单条目的单日Facebook使用量表。使用强度主要测量个体与社交媒体的情感联系强度以及社交媒体融入个体生活的程度, 代表性的工具有Ellison等(2007)编制的Facebook使用强度量表, 为单维度结构, 包含8个题目, 如“Facebook已经成为我日常生活的一部分”。使用成瘾主要测量个体对社交媒体的依赖性, 代表性的工具有Andreassen等(2012)编制的卑尔根Facebook成瘾量表, 为单维度结构, 共6个题目, 如“若停止使用Facebook会变得焦躁不安”。总体而言, 目前关于社交媒体使用的衡量标准并未统一, 因而测量结果较为多样化, 测量工具也较为分散, 其中社交媒体使用强度和社交媒体使用成瘾在当下研究中使用较多。

错失焦虑又译为错失恐惧, 是指对于错失某些可能的重要信息或新奇事件而产生的一种以焦虑为主, 并伴有恐惧、失落、担忧、沮丧等消极感受的弥散性复合情绪体验(Przybylski et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2020)。不仅包括错失前的担心和恐惧, 也包括错失后的不安和失落; 不仅恐惧于遗漏重要的信息, 也恐惧于错过于重要的社会活动和体验; 不仅担心错过他人的新奇体验或重要事件, 也害怕错过自己希望获得的积极体验。强烈期待了解他人经历、频繁参与社交活动、持续关注外界信息动态等都是其典型表现(柴唤友等, 2018)。目前常用的测量工具有Przybylski等(2013)编制的错失焦虑量表(Fear of Missing Out scale, FoMOs-P), 为单维度结构, 共10个题目。该量表在中国由李琦等(2019a)正式修订, 删掉2题后, 修订为包含错失信息焦虑和错失情境焦虑的双维度错失焦虑量表(Fear of Missing Out scale, FoMOs-L)。FoMOs-P结构较为单一, 覆盖的内容可能不全面, 为此, Wegmann等(2017)结合在线情境编制了错失焦虑量表(Fear of Missing Out scale, FoMOs-W), 共12个题目, 包含状态和特质错失焦虑两个因子。肖曼曼和刘爱书(2019)对该量表进行了中文版修订, 最终删掉特质错失焦虑分维度中的一个题目后, 形成了包含11个题目的双维度结构。此外, 宋小康等(2017)还结合移动社交媒体环境编制了错失焦虑症量表, 共16个题目, 包含心理动机、认知动机、行为表现和情感依赖四个因子。最近, Zhang等(2020)还基于自我概念的视角开发了错失焦虑量表(Fear of Missing Out scale, FoMOs-Z), 包含个人和公众错失焦虑两个维度, 共9个题目。总体而言, 目前在研究中使用最多的是FoMOs-P。虽然目前关于错失焦虑的测量工具日趋多样化, 但除了FoMOs-Z以外, 其它量表大都是以FoMOs-P为蓝本进行的修订、删减或丰富。

1.2 社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系

关于社交媒体使用和错失焦虑的关系, 目前主要存在两种观点:第一种观点认为两者呈正相关。第二种观点认为两者线性相关较弱, 可能呈现U形关系。

第一种观点认为社交媒体使用与错失焦虑呈正相关。根据大众传播的社会认知理论(Social cognitive theory of mass communication), 社交媒体使用可能会强化用户的某些认知、情感、态度及行为(Bandura, 2001; Valkenburg et al., 2016)。该观点强调社交媒体使用可能会增加个体的错失焦虑水平(Slater, 2007; Valkenburg et al., 2016)。社交媒体上呈现的大量信息增加了个体对错失活动的可知性。个体在使用过程中由于知晓了大量未参与的事情或活动, 因而会体验到紧张、不安以及被排斥的感觉, 这种相对剥夺感导致了错失焦虑的出现(Baker et al., 2016; Buglass et al., 2017; Hunt et al., 2018)。不仅如此, 由于社交网站上呈现的信息极具炫耀性和夸张性, 浏览此类信息还增加了个体上行社会比较的可能, 使其认为他人的经历比自己的更精彩, 也会导致错失焦虑的出现(Bloemen & Coninck, 2020; Burnell et al., 2019; Yin, Wang, et al., 2019)。此外, 个体在社交媒体上的线上交流、娱乐消遣和无目的的闲逛行为会占用大量的时间, 这会挤占个体用于线下社会互动和人际交往的机会与时间, 使个体错过更多有意义的经历(Alt, 2018; Beyenset al., 2016; Duvenage et al., 2020)。而虚拟的社交平台上所展示的信息仅是现实生活中的一少部分, 无法替代个体的亲身经历和体验。个体在线上时间的消耗中会更加担心是否错过了现实情境中的某些重要的活动或信息, 也会增加错失焦虑感(Bruggeman et al., 2019; Coyne et al., 2020; 李巾英, 马林, 2019)。横向和纵向研究均发现社交媒体使用确实能够正向预测错失焦虑水平(Buglass et al., 2017; 李巾英, 马林, 2019; Yin, Wang, et al., 2019)。

另外一种观点则认为社交媒体使用与错失焦虑线性相关较弱, 可能呈现U形关系。根据数字恰到好处假说(Digital goldilocks hypothesis), 在数字媒体极其普遍的时代, 社交媒体使用已变成一种潮流, 只有顺应潮流, 适度参与和使用才会对个体的心理社会适应产生助力作用。反之, 无论是过度使用还是排斥使用均会对个体的心理社会适应产生不良影响(Przybylski & Weinstein, 2017)。社交媒体使用过多的用户可能会增加自身的完型倾向, 这会推动个体持续关注和跟进当下的新颖信息或事件动态, 使个体更加害怕错过遗漏一些重要或精彩的事件(Yin, Wang, et al., 2019)。社交媒体使用过少的用户由于难以及时获得外界的有效信息以及他人的活动状态, 增加了错过的风险, 因此也会令人心生疑虑和担心(Lai et al., 2016)。只有适度使用社交媒体的用户, 才能将线上和线下活动合理安排, 理性的看待和关注外界的动态, 减少错失焦虑的出现。目前关于社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的U形关系尚未有直接的证据支持, 但确有研究发现社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的线性相关不显著(Bailey et al., 2018; Franchina et al., 2018; Gezgin, 2018; Traş & Öztemel, 2019)。

综上, 大众传播的社会认知理论不仅获得了横向研究和纵向研究的证据支持, 从数字媒体使用与心理健康的大领域来看, 该理论也具有较为广泛的适用性, 得到了众多研究的支持(Faelens et al., 2021; Jagtiani et al., 2019; Keles et al., 2020)。数字恰到好处假说则属于近年来提出的新观点, 目前仅在数字媒体使用与幸福感的关系中得到了支持(Przybylski & Weinstein, 2017), 而在数字媒体使用与抑郁间的关系中未获支持(Houghton et al., 2018), 其适用性尚待进一步验证。由此, 本研究提出假设1:社交媒体使用与错失焦虑存在一定程度的正相关。

1.3 社交媒体使用与错失焦虑关系的调节变量

性别可能影响社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系。首先, 男性和女性对媒体使用的偏好程度不同。男生偏好于游戏类应用, 而女生则对社交类应用情有独钟(Balta et al., 2020; Casale et al., 2018; Coyne et al., 2020)。从暴露理论的视角来看(Brown & Bobkowski, 2011), 由于女性的社交媒体使用水平更高, 其更有可能了解到他人经历但自己未曾体验过的活动, 会对错过的经历和信息产生更多的担心和恐惧(Bloemen & Coninck, 2020; 张永欣等, 2019)。此外, 元分析发现男生比女生的情绪调节能力更强(何相材等, 2019)。面对社交媒体上他人呈现的炫耀性信息和精彩体验, 男生可能更加从容和乐观, 错失焦虑水平更低, 而女生则更有可能表现出担忧和不安, 错失焦虑水平较高(李巾英, 马林, 2019)。综上, 本研究提出假设2:性别能够调节社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系, 女性群体中两者的相关更强。

年龄也可能对社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系产生影响。首先, 就社交媒体的可访问性而言, 青少年社交媒体的注册及使用频率和时间会受到一定程度的约束和监管(Traş & Öztemel, 2019), 而成年人则不受此类情况的限制, 更有条件在社交媒体上浏览大量的信息, 并产生持续关注、害怕错过的心理反应(Huguenel, 2017; Liu, Ainsworth et al., 2016)。此外, 就社会交往的范围而言。成年人往往比青少年更加广泛, 并且成年人朋友圈里的人往往异质性比较高(不同的生活状态和条件), 而青少年朋友圈里的人往往同质性比较高(相似的学习环境)。这使得成年人在使用社交媒体时浏览到他人发布的信息更多, 也更有可能发现自己未曾体验过的经历, 因而会产生更多的担忧和不安, 生怕遗漏他人有意义的信息(Baker et al., 2016; Buglass et al., 2017)。综上, 本研究提出假设3:被试年龄能够调节社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系, 年龄越高两者的相关越强。

社交媒体使用的测量指标也可能会对社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系产生影响。社交媒体使用衡量的标准并不相同。社交媒体使用频率、使用时间和使用强度是社交媒体日常使用习惯的一种反映(Buglass et al., 2017; Ellison et al., 2007)。社交媒体使用成瘾主要借鉴精神疾病的诊断和统计手册(DSM-IV)中物质成瘾和行为成瘾的标准衡量社交媒体过度使用的症状学特征(Andreassen et al., 2012; Monacis et al., 2017), 反映的是个体对社交媒体的依赖程度, 因此该指标有可能对错失焦虑产生更大的影响。类似元分析也发现, 社交媒体使用不同指标与抑郁的关系存在显著差异, 使用成瘾与抑郁的关系比使用强度和使用频率与抑郁的关系更强(刘诏君等, 2018)。综上, 本研究提出假设4:社交媒体使用的测量指标能够调节社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系。

错失焦虑测量工具也可能会对社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系产生影响。首先就问卷的题目数量而言, 一些中文版的修订问卷, 如FoMOs-L是在完整版的问卷——FoMOs-P的基础之上修订来的。其在修订过程中删掉了一些不符合测量标准的题目, 这可能使其在测量过程中损失掉一些信息, 从而导致测量效果存在差别。其次, 就问卷结构而言, FoMOs-P是单维度结构, 主要测量一般情境下的错失焦虑易感性水平。另外一些问卷, 如FoMOs-W则是二维度结构, 不仅测量了错失焦虑的易感性, 还测量了在线情境下产生的错失恐惧状态, 测量的更加全面, 这也可能导致测量结果存在差别。综上, 本研究提出假设5:错失焦虑测量工具够调节社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系。

社交媒体类型也可能会对社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系产生影响。媒体丰富性理论认为, 不同媒体信息呈现的丰富性存在差异, 使用时对个体产生的影响也存在差别(Daft & Lengel, 1986; Liu, Baumeister, et al., 2019)。以图像为中心的社交平台(如Instagram)可能比以文字为主要内容的社交平台(如Twitter)反映的信息更加多彩、直观和形象, 更能激发上行社会比较(Burnell et al., 2019; Franchina et al., 2018; Marengo et al., 2018), 因而个体使用此类社交媒体引发的错失焦虑感可能更高。一项实证研究也发现, Snapchat使用与错失焦虑的相关为0.17, 而Twitter使用与错失焦虑的相关为0.06, 二者存在明显差别(Franchina et al., 2018)。类似地, 英国的一项权威报告显示, 不同社交媒体对幸福感和心理健康的影响存在差异。其中Instagram对个体幸福感的消极影响排在首位, Snapchat位居其次(Royal Society for Public Health, 2017)。综上, 本研究提出假设6:社交媒体类型能够调节社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系。

社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系还可能受文化背景的影响。集体主义倾向较高的文化, 强调相互依存, 个体受周围的人际环境影响较大, 这使得个体在社交媒体使用时更加关注别人的动态。当看到朋友正在从事一项他们未曾参与的活动时, 更可能会体验到被排斥的感觉, 并因此感到紧张和不安, 害怕错过一些重要的信息和精彩的体验(Alt, 2018; Huguenel, 2017)。个体主义倾向较高的文化, 则强调独立性和自主性, 个体受周围人际环境影响较小, 因而在社交媒体使用的过程中较少体验到错失焦虑感(Yin, de Vries et al., 2019)。类似的元分析也发现, 集体主义文化中, 社交媒体使用与自尊的相关要强于个体主义文化(Liu & Baumeister, 2016)。综上, 本研究提出假设7:文化背景能够调节社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系, 个体主义倾向越高, 两者的相关越弱。

总之, 目前关于社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系, 不仅在理论上存在着争论, 在实证研究过程中也存在不一致的研究结果。鉴于两者在现实生活中都表现的相对普遍且会对人们的工作和生活产生重要影响。所以, 两者存在何种关系, 对于社交媒体使用的合理引导以及错失焦虑的教育矫正或社区干预有着重要的参考价值。但目前尚未有研究从宏观和整合的视角对此予以澄清, 因而通过元分析的手段估计社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的相关强度以及背后的影响因素十分必要。这样不仅在理论上有助于初步澄清大众传播的社会认知理论和数字恰到好处假说间的争议, 对数字媒体使用与心理健康领域的研究也是一种有益补充。在实践上, 还有助于揭示社交媒体使用与错失焦虑存在联系的具体条件, 为重度社交媒体使用者及错失焦虑人群提供更为贴切的生活建议和疏导方案。

2 方法

2.1 文献检索与筛选

由于错失焦虑是近年来才被关注的现象, 研究数量总体适中, 故搜索策略中仅对该变量进行限定, 对社交媒体使用不做限定, 以便更全面的纳入研究两者关系的文献。首先, 在中文数据库中(中国知网期刊和硕博论文数据库、万方期刊和学位论文数据库及维普期刊数据库), 搜索篇名或摘要中包含关键词“错失焦虑”或“遗漏焦虑”或“错失恐惧”的文献。其次, 在英文数据库中(Web of Science核心合集, ElsevierSD, Springer Online Journals, Medline, EBSCO-ERIC, SAGE Online Journals, Scopus, PsycINFO, PsycArticles和ProQuest Dissertations and Theses)检索篇名或摘要中包含关键词“Fear of Missing out”或“FoMO”的文献。检索截止日期为2020年1月, 共获取文献977篇。此外, 为了避免遗漏, 通过文献阅读过程中的引文及文献更新进行文献补充, 最近一次文献更新为2020年12月。

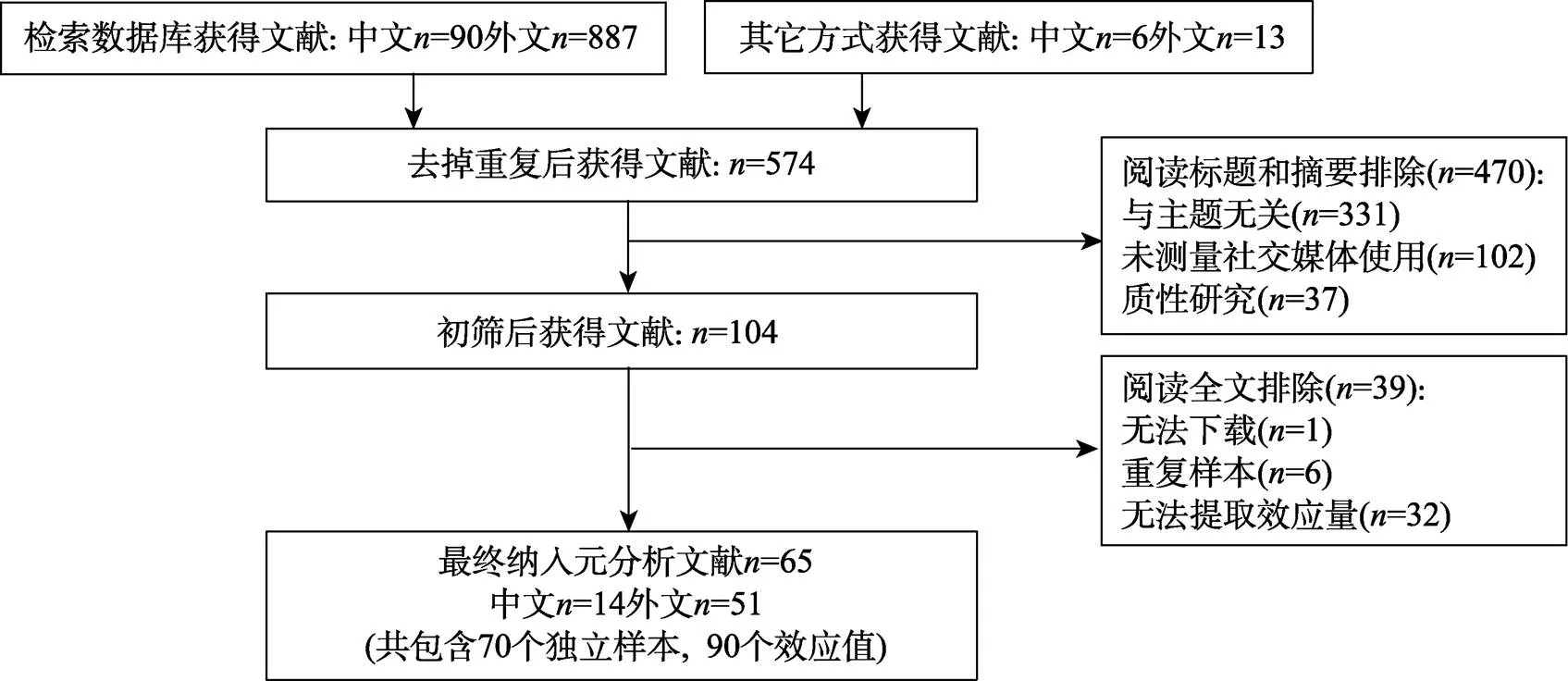

使用EndNote X9导入文献并按照如下标准筛选:(1)须为调查或实验类的实证研究, 排除纯理论和综述类及质性研究; (2)同时测量了社交媒体使用和错失焦虑, 并至少报告了一个量表的各维度或总分与另一个量表的各维度或总分之间的积差相关系数(), 或者能转化为的值、值、χ值或一元线性回归中的值。偏相关系数和其他类型的相关系数(如等级相关)将被排除; (3)所选研究不限于期刊论文, 还包括学位论文、会议全文和书的章节等; (4)数据重复发表的仅取其中内容报告较为全面的一篇; (5)研究对象为一般人群, 贫困生、留守儿童等特殊群体将被排除。(6)样本量大小明确。文献筛选流程见图1。

2.2 文献编码与质量评价

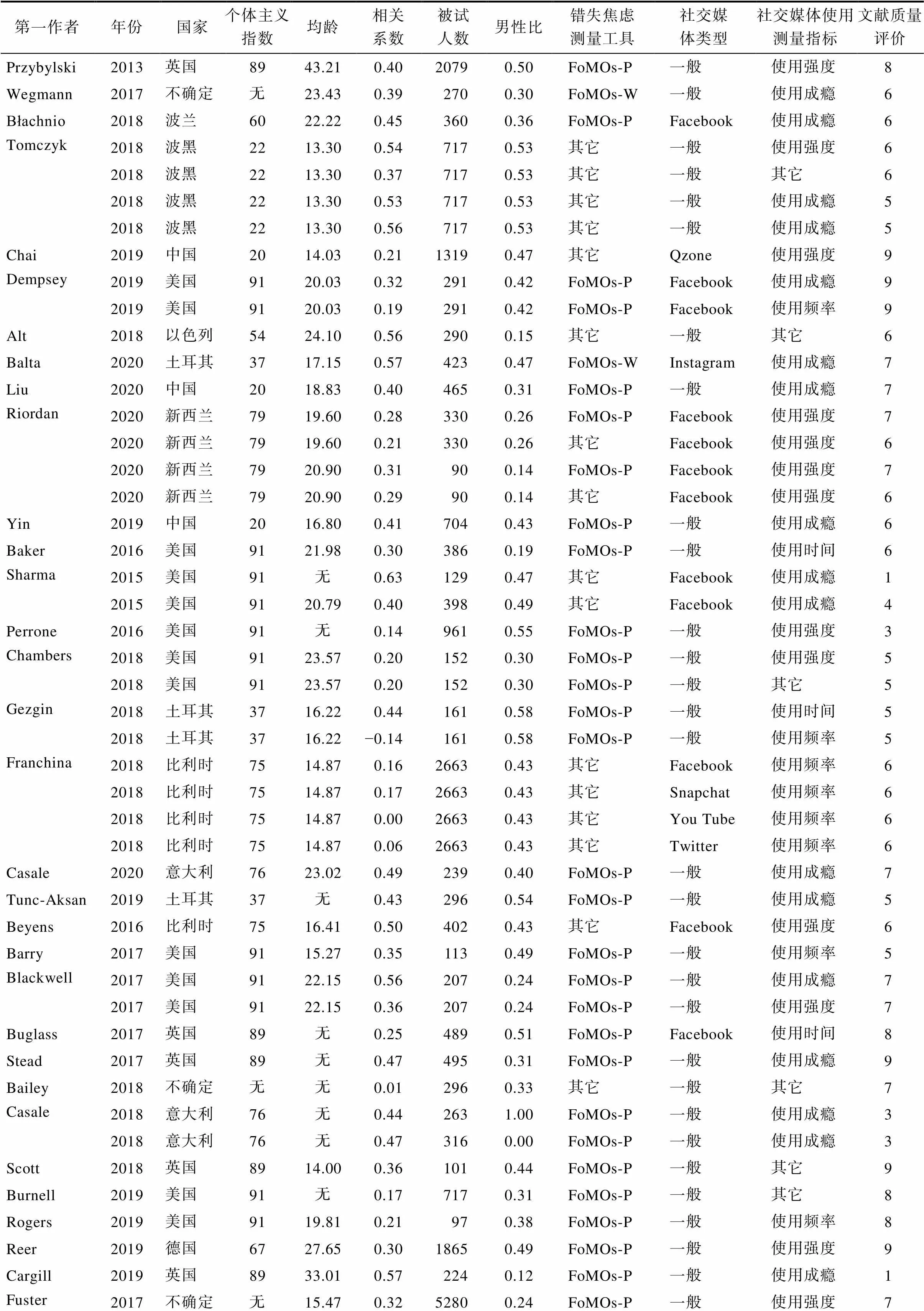

每项研究根据以下特征进行编码:作者、出版年、被试国籍、个体主义指数、平均年龄、相关系数、有效人数、男性比例、错失焦虑测量工具、社交媒体类型、社交媒体使用测量指标和文献质量评价指数(见表1)。编码时遵循以下原则:(1)效应值的提取以独立样本为单位, 每个独立样本编码一次, 若同一篇文献调查了多个独立样本, 则分别对应进行编码; (2)若文献仅按被试特征(如男/女)分別报告了相关, 则分别编码; (3)若研究是纵向研究, 则按首次测量结果进行编码。(4)若同一研究同时测量了多个变量指标, 则分别针对各个指标进行编码。

采用张亚利等(2019)编制的相关类元分析质量评价表, 从抽样方法、数据有效率、刊物级别、测量工具的内部一致性信度对纳入的原始研究进行质量评价。本研究中每篇文章的评价总分介于0~10之间, 得分越高表明文献质量越好(表1)。

2.3 发表偏差控制与检验

发表偏差是指显著的结果更容易被发表(Rothstein et al., 2005), 因此, 已出版的文献并不能全面地代表该领域已经完成的研究总体。本研究纳入文献时不仅纳入了已出版的期刊和会议论文, 还纳入了未出版的毕业论文, 一定程度上控制了发表偏差对研究结果的干扰。此外, 为保证元分析结果的可靠性, 本研究还将利用漏斗图(Funnel plot)、Egger’s回归法以及剪补法(trim and fill method)评估是否存在发表偏差。对于漏斗图而言, 如果图形呈现一个对称的倒漏斗形状, 则表明发表偏差较小, 对元分析结果的影响较小(Light & Pillemer, 1984); 对于Egger’s回归而言, 如果线性回归的结果不显著, 则表明发表偏差较小(Egger et al., 1997); 剪补法基于发表性偏倚造成漏斗图不对称这一假设, 采用迭代方法剪补一部分研究后, 重新估计矫正后的效应量, 若效应量在剪补前后差异不大, 则表明发表偏差较小(Rothstein et al., 2005)。

图1 文献纳入流程

表1 纳入分析的原始研究的基本资料

续表1

注:相应国家个体主义指数见https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/。错失焦虑工具一列中“其它”表示与现有分类工具不同, 但每种使用量低于3次无法单独归为一组进行分析的工具混合组; 社交媒体类型一列中“一般”表示原始研究中未区分特定社交媒体的情况; 社交媒体使用测量指标一列中“其它”表示与现有分类测量指标不同, 但每种使用量低于3次无法单独归为一组进行分析的指标混合组(如课堂社交媒体使用、睡前社交媒体使用、被动性社交媒体使用等)。

2.4 模型选择

目前, 计算效应大小的方法主要有两种:固定效应模型和随机效应模型。前者假设不同研究的实际效果是相同的, 而结果之间的差异是由随机误差引起的。后者假设不同研究的实际效果可能不同, 而且不同的结果不仅受随机误差的影响, 而且还受不同样本特征的影响(Schmidt et al., 2009)。通过文献梳理, 本研究认为社交媒体使用测量指标等因素可能影响社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系, 因此本研究采用随机效应模型进行估计。此外, 本研究还通过异质性检验, 对随机效应模型选择的适切性进行验证, 主要查看检验结果的显著性以及值两个指标。若检验结果显著或的值高于75%, 则选择随机效应模型更合适, 反之, 选用固定效应模型更合适(Huedo-Medina et al., 2003)。

2.5 数据处理

本研究采用相关系数作为效应值指标。使用软件Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 3.3 (Borenstein et al., 2014)进行元分析主效应检验和调节效应检验。估计平均效应值的过程中, 为保证效应值的独立性, 当某一研究出现多个效应值时, 采用CMA 3.3软件中的效应值平均化合并功能, 将研究中的多个效应值合并后再估计整体效应值。调节效应分析采用元回归分析并结合极大似然法考察结果是否显著。本研究中调节变量涉及:(1)连续调节变量。包括每个研究中被试的平均年龄; 每个研究中男性占被试总数的比例, 以及被试所在国家或地区的个体主义指数。(2)分类调节变量。包括社交媒体使用测量指标(结合测量工具的名称和内容分为使用成瘾、使用强度、使用时间和使用频率四类)。社交媒体类型(依据研究目的和原始研究特征分为Snapchat、Facebook和Instagram三种)。错失焦虑测量工具(结合原始研究使用的工具称谓分为FoMOs-P、FoMOs-L和FoMOs-W三种)。此外, 亚组分析时为了保证调节变量每个水平下的研究均能代表该水平, 参照既有研究(Song et al., 2014), 每个水平下的效应量个数应不少于3个。

3 结果

3.1 文献纳入与质量评价

本研究共纳入研究65项(含70个独立样本, 90个效应值, 61893名被试), 包括硕博论文10篇, 期刊论文54篇, 会议论文1篇; 中文文献14篇, 英文文献50篇, 西班牙文文献1篇; 时间跨度为2013~2020年。本研究中文献质量评价得分的均值为6, 高于理论均值(5分), 其中19个效应值的文献质量评分低于理论均值, 约占效应值总数的21%, 需谨慎对待此类文献对研究结果的影响。

3.2 异质性检验

本研究对纳入的效应量进行异质性检验, 以便确定采用随机效应模型是否恰当, 以及是否有必要进行调节效应分析。检验结果表明,值为1288.69 (< 0.001),值为94.65%, 超过了Huedo-Medina等(2006)提出的75%的法则。说明结果异质, 也表明纳入的有关社交媒体使用与错失焦虑关系的效应量中有94.65%的变异是由效应值的真实差异引起的, 接下来的分析选用随机效应模型是恰当的。该结果也提示不同研究间的估计值差异可能受到了一些研究特征因素的干扰, 可进行调节效应分析。

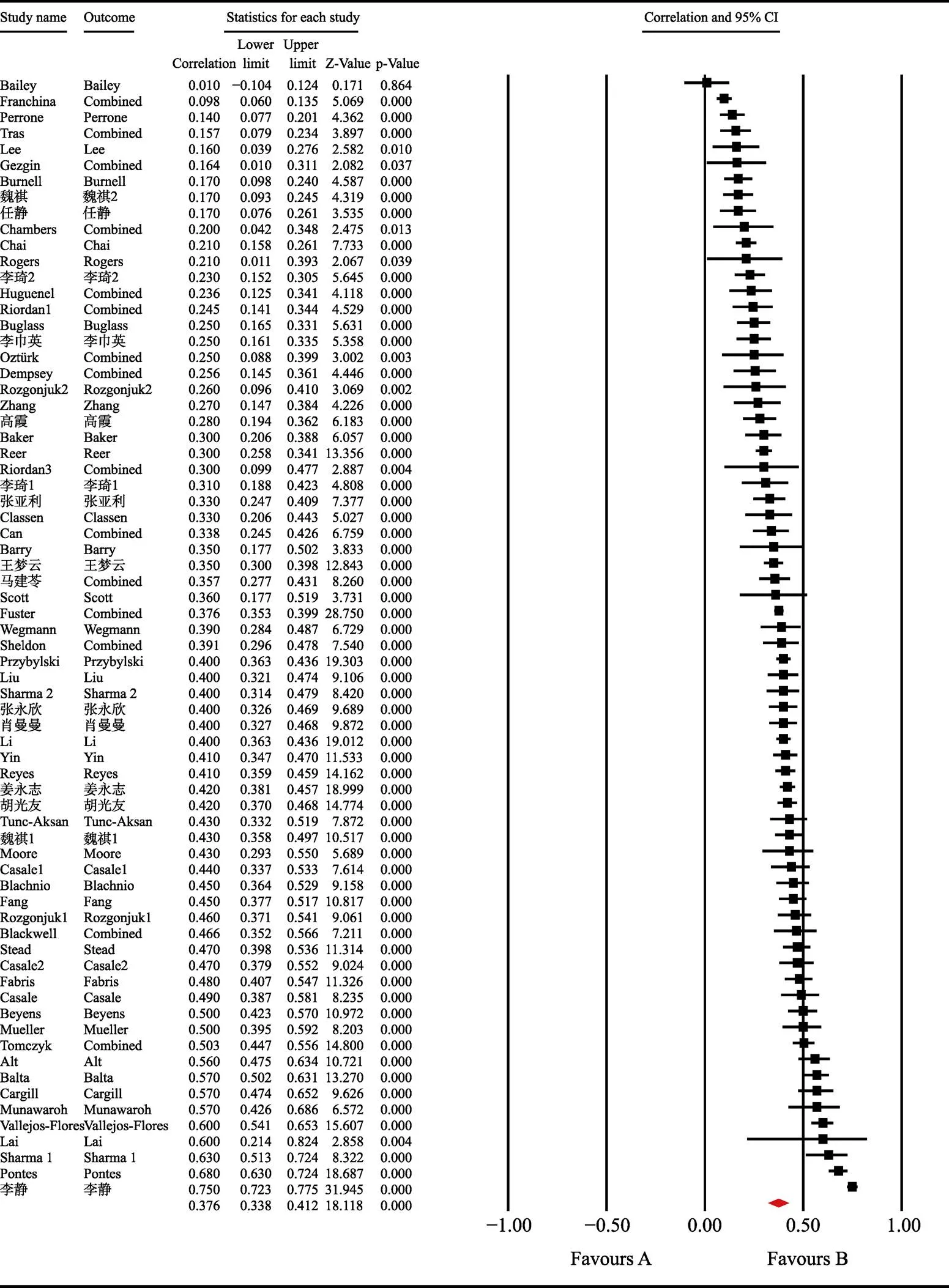

3.3 主效应检验

采用随机效应模型对合并后形成的70个独立样本进行估计, 结果显示社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的相关强度为0.38, 95%的置信区间为[0.34, 0.41], 不包含0 (图2)。根据Gignac和Szodorai (2016)提出的最新判断标准, 社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的相关程度大于0.3, 表明二者存在高相关。敏感性分析发现, 排除任意一个样本后的效果量值在0.367 ~ 0.380之间浮动。根据文献质量评分, 删除低于5分的19个效应值后(见表1), 重新对结果进行估计, 发现社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的效果量= 0.37,< 0.001。以上结果均表明元分析结果具有较高的稳定性。

3.4 调节效应检验

利用元回归分析检验调节变量对社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系是否有显著影响, 结果发现:(1)性别对社交媒体使用与错失焦虑关系的调节作用不显著。元回归分析发现, 男性比例对效应值的回归系数不显著(= 0.03, 95% CI [−0.22, 0.28])。(2)年龄对社交媒体使用与错失焦虑关系的调节效应不显著。元回归分析发现, 平均年龄对效应值的回归系数不显著(= −0.001, 95% CI [−0.008, 0.007])。(3)元回归分析发现, 社交媒体使用测量指标对社交媒体使用与错失焦虑关系的调节效应显著。社交媒体使用成瘾与错失焦虑的相关最高, 社交媒体使用频率与错失焦虑的相关最低, 且为边缘显著。配对比较结果发现, 除使用强度和使用时间之间差异, 以及使用时间和使用频率差异不显著外, 其它配对比较差异均显著。(4)元回归分析发现, 错失焦虑测量工具对社交媒体使用与错失焦虑关系的调节效应不显著。(5)元回归分析发现, 社交媒体类型对社交媒体使用与错失焦虑关系的调节效应显著。Instagram使用与错失焦虑的相关最高, Snapchat与错失焦虑的相关最低。配对比较发现, 除Facebook与Snapchat差异不显著外, 其它配对比较差异均显著。(6)文化背景对社交媒体使用与错失焦虑关系的调节作用不显著。元回归分析发现, 个体主义指数对效应值的回归系数不显著(= –0.001, 95% CI [–0.002, 0.001])。分类变量调节效应分析结果详见表2。

图2 每个独立样本的效应量及总体效应量的森林图

3.5 发表偏差检验

漏斗图显示, 效应值集中在图形上方且均匀分布于总效应的两侧; Egger线性回归的结果不显著, 截距为0.89, 95% CI [−1.40, 3.19]; 剪补法的结果发现, 向右侧剪补11项研究后,调整为0.41, 95% CI为[0.38, 0.45], 结果显著。剪补后效应量略高于矫正前的效应量(= 0.38), 但两者仅相差0.03, 且修正后的结果仍为高相关, 说明本研究不存在明显的发表偏差。

4 讨论

4.1 社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系

有关社交媒体使用与心理健康关系一直是研究关注的焦点。近来诸多研究针对社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系进行了探讨, 但研究结果却存在很大差异(Franchina et al., 2018; Gezgin, 2018; 李巾英, 马林, 2019; Pontes et al., 2018; Tunc-Aksan & Akbay, 2019; 张亚利等, 2020), 给该领域的深入研究带来了困扰。目前却尚未有研究对此予以澄清, 本研究借助元分析的方法首次对两者的相关强度从整体上进行了估计, 结果表明社交媒体使用与错失焦虑存在高相关。该结果验证了假设1, 一定程度上支持了大众传播的社会认知理论(Bandura, 2001; Valkenburg et al., 2016)的观点, 表明社交媒体使用和错失焦虑存在线性相关, 而数字恰到好处假说(Przybylski & Weinstein, 2017)的观点则有待进一步检验。本研究也澄清了社交媒体使用与错失焦虑相关性大小方面存在的争论, 支持了目前的多数研究结果(Balta et al., 2020; Liu & Ma, 2020; Reyes et al., 2018; Yin, Wang, et al., 2019), 未支持两者之间存在中低程度相关, 甚至相关不显著的结果(Bailey et al., 2018; Franchina et al., 2018; Gezgin, 2018; Traş & Öztemel, 2019), 说明社交媒体使用与错失焦虑关系颇为密切。

本结果一定程度上支持了大众传播的社会认知理论(Bandura, 2001; Valkenburg et al., 2016), 表明社交媒体使用与错失焦虑存在线性关系。社交媒体使用的增加往往会导致错失焦虑水平的增加。这种媒体效应类似于“武器效应” (Berkowitz, 1989), 原因在于社交媒体所具有的自我呈现和实时更新功能增加了未知事件的可感知性。个体通过浏览朋友及重要他人在社交平台上暴露的大量信息, 能够知晓更多未曾参与的精彩活动和体验, 这增加了个体内心的被排斥感(Baker et al., 2016; Bloemen & Coninck, 2020; Buglass et al., 2017)。更重要的是, 社交平台上的信息往往经过了用户的精心修饰和编辑, 充满了炫耀性和夸张性(Brown & Kuss, 2020)。这又会使个体心生嫉妒, 认为别人的生活比自己过的更加精彩和有意义, 因而会对此类信息保持高度的关注, 时刻担心错过一些重要的信息和精彩的经历(Burnell et al., 2019)。古语言“眼不见, 心不烦”, 反过来, “眼见可能会招致心烦”。生活在信息爆炸的时代, 个体看到的信息多了亦会对错过的以及可能错过的信息和经历产生莫名的恐惧和担忧, 因而体验到的错失焦虑会更多(Basu & Banerjee, 2020; Bloemen & de Coninck, 2020)。除此之外, 社交媒体的使用尤其是过度使用还会占用个体的线下活动时间, 这可能会使个体错过线下参与他人活动的机会(Alt, 2018)。如有研究显示有24%的人由于在社交媒体上的浏览和分享导致错过了生活中的某些重要时刻(Shensa et al., 2020), 从而令个体体验到更多的不安和焦虑(Beyens et al., 2016; Duvenage et al., 2020)。

表2 分类变量调节效应分析结果

注:代表效应值的数量;Q代表异质性检验统计量。

本研究虽未能直接验证社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的U形关系, 但结果发现两者存在高相关(Gignac & Szodorai, 2016), 且高于百年来社会心理学研究中的平均相关性0.21 (Richard et al., 2003)。该结果表明二者可能呈现的是典型的线性关系, 而数字恰到好处假说(Przybylski & Weinstein, 2017)的观点则有待进一步验证。事实上, 当下研究中对该观点也存在争论, 如有研究发现社交媒体使用与幸福感的关系呈现出二次函数的关系, 回答“每周使用几次”的人比回答“几乎每天使用”和“从不使用”的人幸福感更高(Bruggeman et al., 2019), 但也有研究发现, 数字媒体使用与抑郁间不呈U型关系(Houghton et al., 2018)。未来应检验该观点是否仅限于探讨社交媒体使用与积极心理变量间的关系(Houghton et al., 2018)。另外, 本结果得到的社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的相关为0.35, 高于以往元分析中关于社交媒体使用与孤独感(= 0.11)、抑郁(= 0.13)及压力(= 0.13)等内化问题的相关(Liu, Baumeister et al., 2019), 说明社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系比与孤独感、抑郁及压力的关系更为密切。

4.2 调节效应分析

元分析从宏观上得出的社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的总体相关程度, 并不是对既有研究中未获得支持的个别研究的否定和推翻, 两者的关系很可能受到了某些变量的调节或干扰, 本研究通过检验发现:

从被试特征来看。性别和年龄对社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的调节作用均不显著, 未支持假设2和假设3, 说明社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系中存在跨性别和跨年龄的趋同效应。该结果支持了某些实证研究中得到的结果(Barry et al., 2017; Burnell et al., 2019; Casale et al., 2018; Tomczyk & Selmanagic-Lizde, 2018; Wegmann et al., 2017), 也与某些类似的元分析结果一致。如有元分析发现, 社交媒体使用与抑郁以及心理幸福感的关系同样不受性别和年龄因素的影响(Huang, 2017; Liu, Baumeister et al., 2019; 刘诏君等, 2018; Vahedi & Zannella, 2019)。说明随着社交媒体不断迭代和更新, 其提供的内容可能越来越能够满足用户个性化的需求, 因而对不同性别及不同年龄的群体同样具有吸引力(Dempsey et al., 2019; 张亚利等, 2020)。如最近关于美国的一项调查显示, 主流媒体Facebook使用的年龄差异并不明显, 在各个年龄段中都相对普遍, 这可能给不同年龄段和不同性别的个体带来相似的影响, 如催生错失焦虑和抑郁等不良情绪(刘诏君等, 2018 ;Vahedi & Zannella, 2019)。但本研究中涉及的年龄群体未涵盖儿童和老年人, 在结果的推广上需要注意。

从测量特征来看。首先, 社交媒体使用测量指标对社交媒体使用与错失焦虑关系的调节作用显著。社交媒体使用成瘾与错失焦虑的相关要强于社交媒体使用频率、社交媒体使用时间和社交媒体使用强度。结果验证了假设4, 支持了某些实证研究中的结果(Can & Satici, 2019; Dempsey et al., 2019), 也同社交媒体使用与抑郁(刘诏君等, 2018; Vahedi & Zannella, 2019)及自尊(Saiphoo et al., 2020)的元分析结果类似。原因在于衡量社交媒体使用的标准不同。社交媒体使用强度、频率和时间反映的是个体的日常使用习惯或非病理性状态。社交媒体使用成瘾反映的是一种过度使用、失去控制的病理性状态。个体在使用过程中不仅时间损耗多, 而且卷入程度深, 往往会对社交媒体形成依赖性, 因而对个体的心理健康影响更大, 伴随的错失焦虑感更高(Buglass et al., 2017; 马建苓, 刘畅, 2019; Monacis et al., 2017)。其次, 错失焦虑测量工具对社交媒体使用与错失焦虑关系的调节作用不显著, 未支持假设5。这可能反映了三种测量工具的趋同性。FoMOs-L属于FoMOs-P的修订版, 在修订过程中虽然删除了2个题目, 但本结果发现, 其并没有造成明显的测量衰减, 甚至在剔除了一些不合时宜的题目后与错失焦虑的相关比原量表略高。FoMOs-W属于FoMOs-P的改编版, 虽然加入了一些新项目, 但12个题目中仍以FoMOs-P为主, 保留了其中的7个项目, 所以两者与社交媒体使用的相关相差无几。

从媒体特征来看。社交媒体类型对社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系的调节效应显著, 结果支持了假设6。首先, Instagram使用与错失焦虑的相关要高于Facebook。两者均包含图像内容, 但Facebook是一种综合性的社交媒体, 且内容以文本为主(de Lenne et al., 2020)。Instagram完全以图像为导向, 以一种快速、美妙和有趣的方式将随时抓拍下的图片彼此分享, 其提供信息的即时性、精彩性和丰富性更强, 个体对其向往程度更高, 会更担心错失这种新奇的体验(Rozgonjuk et al., 2020; Scott & Woods, 2018)。此外, 接触此类带有积极化偏向的图像信息会导致认知偏差——认为他人的体貌特征更好、生活更多彩。这会激起个体更多的错失焦虑感, 促使其产生持续关注他人动态变化的心理欲求(吴漾等, 2020)。其次, Instagram使用与错失焦虑的相关比Snapchat要高。两者的内容均以图像为导向, 但Instagram具有开放性, 用户信息接收的范围更广。Snapchat具有封闭性, 大多是熟人社交, 信息接受的范围较窄(Franchina et al., 2018), 并且Snapchat用户主要使用该平台发送幽默性内容, 而非个人的新颖动态(Burnell et al., 2019), 因而激起的错失焦虑感比Instagram少。最后, Facebook使用与Snapchat使用同错失焦虑的相关差异不显著。这可能是因为两者都具有封闭性(Franchina et al., 2018), 使得个体的社交范围和信息接受范围受限, 导致媒体上熟人的社交信息带给个体的心理冲击类似(Thorisdottir et al., 2019), 因而与错失焦虑的相关无显著差异。需注意的是, 国内在该领域的研究处于起步状态, 还少有研究关注具体的社交媒体使用(如, 抖音、微信等)与错失焦虑的关系, 未来可待研究丰富后, 进一步同国外的研究进行详细对比。

从文化特征来看。个体主义指数对社交媒体使用与错失焦虑关系的调节作用不显著, 未支持假设7, 表明两者关系可能存在跨文化趋同效应。其它有关网络使用与抑郁和孤独感的元分析(Tokunaga, 2017), 以及社交媒体使用与心理幸福感的元分析(Liu, Baumeister et al., 2019)也未发现文化差异。这可能与全球文化的融合有关, 东方国家虽然受传统文化的影响, 集体主体色彩较为浓厚, 但随着时代的变迁, 全球文化呈现出的是集体主体式微, 个体主义上升, 多元文化共存的局面。因此, 社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系受文化影响的程度较小(Cai et al., 2018; 黄梓航等, 2018)。最近的研究也的确发现, 社交媒体使用和错失焦虑在全球范围内都成为了较为普遍的现象(Baker et al., 2016; Reyes et al., 2018; Traş & Öztemel, 2019)。但值得注意的是, 全球文化的分类目前仍然存在着争论。本研究参照既有研究(Liu, Baumeister et al., 2019)仅尝试从集体主义和个体主义的角度切入, 对社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系进行了探讨。基于本研究的开放数据, 将来仍可进一步开展跨文化的比较分析。

4.3 研究意义、不足与展望

本研究利用元分析从总体上探讨了社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的相关强度以及可能的调节因素, 初步澄清了目前大众传播的社会认知理论和数字恰到好处假说之间的争论, 为该主题的深入研究提供了证据支持。首先, 本结果发现社交媒体使用与错失焦虑存在高相关, 说明两者关系颇为密切, 一定程度上支持了大众传播的社会认知理论(Bandura, 2001; Valkenburg et al., 2016), 同时也为该领域开展贝叶斯统计分析提供了信息参照。其次, 本研究还发现社交媒体使用的测量指标能够对社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系产生影响。对于科研工作者而言, 今后开展具体研究时, 可根据具体情况注意选取恰当的测量指标, 以便更加精准的考察两者间的关系。此外, 本研究还发现Instagram这类以图像为中心并且开放度较高的媒体比Facebook这类以文本为中心且开放度较低的媒体与错失焦虑的关系更强。虽然这些媒体并非国内流行的, 但该结果同样对国内的社交媒体使用者具有启示作用。需要特别关注以图像为中心的社交媒体使用, 尤其注意不要过度使用, 以免催生较多的错失焦虑感。最后, 本研究发现社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的相关在不同性别和年龄群体中表现类似。这提示针对本主题的心理健康教育和社会心理服务工作应该注重实施的覆盖面, 构建大中小幼心理健康教育一体化建设新格局(俞国良, 张亚利, 2020), 在不同的年龄阶段均要强调社交媒体的合理使用, 以防止个体出现错失焦虑进而影响其身心健康和生活质量。

本研究也存不足之处, 首先, 由于当下测量社交媒体使用的工具颇为分散, 难以满足调节变量的分组标准, 因此本研究未探讨社交媒体使用测量工具是否影响了两者的关系。将来应注重社交媒体测量工具的标准化, 以便更加精准的把握社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系。其次, 由于亚组分析时个别亚组之间效应值个数差异较大, 这可能会对结果产生一定的影响, 未来待资料丰富后可进一步确认本研究的亚组分析结果是否稳健。此外, 由于目前针对国内特定社交媒体开展的研究较少, 使得国内外的不同社交媒体难以进行对比分析, 未来可基于本研究的开放数据, 待国内研究丰富后进一步加以比较。最后, 本研究在论述时, 仅依据目前的纵向和实验研究结果聚焦于社交媒体使用作用于错失焦虑这一视角, 但元分析得到的结果仅能表明社交媒体使用与错失焦虑存在线性相关, 不能揭示两者间的因果关系。未来还需要展开更加严谨的追踪研究以揭示两者的动态变化规律。

5 研究结论

(1)社交媒体使用与错失焦虑存在显著正相关, 社交媒体使用水平较高的个体错失焦虑水平也更高, 反之亦然; (2)两者的相关受社交媒体使用测量指标的调节, 社交媒体使用成瘾与错失焦虑的相关最高, 社交媒体使用频率与错失焦虑的相关最低; (3)两者的相关受社交媒体类型的调节, 同Snapchat、Facebook相比, Instagram使用与错失焦虑的相关更强; (4)两者的相关不受性别、年龄、错失焦虑测量工具和个体主义指数的调节。

致谢:感谢台州市教育监测与科学研究院助理研究员王洁、南京师范大学胡传鹏博士、宁夏大学丁凤琴博士、西南大学滕召军博士为本文修改提供的宝贵建议。

*元分析用到的参考文献

*Alt, D. (2018). Students’ wellbeing, fear of missing out, and social media engagement for leisure in higher education learning environments.,(1), 128–138.

Andreassen, C. S., Torsheim, T., Brunborg, G. S., & Pallesen, S. (2012). Development of a Facebook addiction scale.,(2), 501–517.

*Bailey, A. A., Bonifield, C. M., & Arias, A. (2018). Social media use by young Latin American consumers: An exploration.,, 10–19.

*Baker, Z. G., Krieger, H., & LeRoy, A. S. (2016). Fear of missing out: Relationships with depression, mindfulness, and physical symptoms.,(3), 275–282.

*Balta, S., Emirtekin, E., Kircaburun, K., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Neuroticism, trait fear of missing out, and phubbing: The mediating role of state fear of missing out and problematic Instagram use.,(3), 628–639.

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory of mass communication.(3), 265–299.

*Barry, C. T., Sidoti, C. L., Briggs, S. M., Reiter, S. R., & Lindsey, R. A. (2017). Adolescent social media use and mental health from adolescent and parent perspectives.,, 1–11.

Basu, S., & Banerjee, B. (2020). Impact of environmental factors on mental health of children and adolescents: A systematic review.. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. childyouth.2020.105515

Berkowitz, L. (1989). Frustration-aggression hypothesis: Examination and reformulation.(1), 59–73.

*Beyens, I., Frison, E., & Eggermont, S. (2016). “I don’t want to miss a thing”: Adolescents’ fear of missing out and its relationship to adolescents’ social needs, Facebook use, and Facebook related stress.,, 1–8.

*Błachnio, A., & Przepiórka, A. (2018). Facebook intrusion, fear of missing out, narcissism, and life satisfaction: A cross-sectional study.,, 514–519.

*Blackwell, D., Leaman, C., Tramposch, R., Osborne, C., & Liss, M. (2017). Extraversion, neuroticism, attachment style and fear of missing out as predictors of social media use and addiction.,, 69–72.

Bloemen, N., & de Coninck, D. (2020). Social media and fear of missing out in adolescents: The role of family characteristics.. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120965517

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L., Higgins, J., & Rothstein, H. R. (2014).. Englewood, NJ: Biostat.

Brown, J. D., & Bobkowski, P. S. (2011). Older and newer media: Patterns of use and effects on adolescents' health and well-being.(1), 95–113.

Brown, L., & Kuss, D. J. (2020). Fear of missing out, mental wellbeing, and social connectedness: A seven-day social media abstinence trial.(12), Article 4566. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124566

Bruggeman, H., van Hiel, A., van Hal, G., & van Dongen, S. (2019). Does the use of digital media affect psychological well-being? An empirical test among children aged 9 to 12.,, 104–113.

*Buglass, S. L., Binder, J. F., Betts, L. R., & Underwood, J. D. M. (2017). Motivators of online vulnerability: The impact of social network site use and FOMO.,, 248–255.

*Burnell, K., George, M. J., Vollet, J. W., Ehrenreich, S. E., & Underwood, M. K. (2019). Passive social networking site use and well-being: The mediating roles of social comparison and the fear of missing out.,(3), Article 5. http://dx.doi.org/10.5817/CP2019-3-5

Cai, H., Zou, X., Feng, Y., Liu, Y., & Jing, Y. (2018). Increasing need for uniqueness in contemporary China: Empirical evidence., Article 554. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00554

*Can, G., & Satici, S. A. (2019). Adaptation of fear of missing out scale (FoMOs): Turkish version validity and reliability study.,, Article 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41155-019-0117-4

Card, N. A. (2012).. New York: Guilford Press.

*Cargill, M. (2019).(Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Akron.

*Casale, S., & Fioravanti, G. (2020). Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Italian version of the fear of missing out scale in emerging adults and adolescents.. Advance online publication. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106179

*Casale, S., Rugai, L., & Fioravanti, G. (2018). Exploring the role of positive metacognitions in explaining the association between the fear of missing out and social media addiction.,, 83–87.

Chai, H. Y., Niu, G. F., Chu, X. W., Wei, Q., Song, Y. H., & Sun, X. J. (2018). Fear of missing out: What have I missed again?(3), 527–537.

[柴唤友, 牛更枫, 褚晓伟, 魏祺, 宋玉红, 孙晓军. (2018). 错失恐惧: 我又错过了什么?,(3), 527–537.]

*Chai, H. Y., Niu, G. F., Lian, S. L., Chu, X. W., Liu, S., & Sun, X. J. (2019). Why social network site use fails to promote well-being? The roles of social overload and fear of missing out.,, 85–92.

*Chambers, K. J. (2018).(Unpublished doctoral dissertation). William James College.

China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC). (2020).. Retrieved August 10, 2020, from http://www.cnnic.net.cn/hlwfzyj/hlwxzbg/hlwtjbg/202004/t20200428_70974.htm

[中国互联网络信息中心. (2020).. 2020-08-10取自http://www.cnnic.net. cn/hlwfzyj/hlwxzbg/hlwtjbg/202004/t20200428_70974.htm]

*Classen, B., Wood, J. K., & Davies, P. (2020). Social network sites, fear of missing out, and psychosocial correlates.,(3), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.5817/ CP2020-3-4

Coyne, S. M., Rogers, A. A., Zurcher, J. D., Stockdale, L., & Booth, M. (2020). Does time spent using social media impact mental health? An eight year longitudinal study.. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.106160

Daft, R. L., & Lengel, R. H. (1986). Organizational information requirements, media richness and structural design.,(5), 554–571.

de Lenne, O., Vandenbosch, L., Eggermont, S., Karsay, K., & Trekels, J. (2020). Picture-perfect lives on social media: A cross-national study on the role of media ideals in adolescent well-being.(1), 52–78.

*Dempsey, A. E., O'Brien, K. D., Tiamiyu, M. F., & Elhai, J. D. (2019). Fear of missing out (FoMO) and rumination mediate relations between social anxiety and problematic Facebook use..Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2018.100150

Duvenage, M., Correia, H., Uink, B., Barber, B. L., Donovan, C. L., & Modecki, K. L. (2020). Technology can sting when reality bites: Adolescents’ frequent online coping is ineffective with momentary stress.,, 248–259.

Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C., & Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook “friends:” Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites.,(4), 1143–1168.

Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test.(7109), 629–634.

*Fabris, M. A., Marengo, D., Longobardi, C., & Settanni, M. (2020). Investigating the links between fear of missing out, social media addiction, and emotional symptoms in adolescence: The role of stress associated with neglect and negative reactions on social media..Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh. 2020.106364

Faelens, L., Hoorelbeke, K., Soenens, B., van Gaeveren, K., de Marez, L., de Raedt, R., & Koster, E. H. W. (2021). Social media use and well-being : A prospective experience- sampling study.Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHB.2020. 106510

*Fang, J., Wang, X., Wen, Z., & Zhou, J. (2020). Fear of missing out and problematic social media use as mediators between emotional support from social media and phubbing behavior..Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106430

*Franchina, V., Vanden Abeele, M., van Rooij, A. J., Lo Coco, G., & de Marez, L. (2018). Fear of missing out as a predictor of problematic social media use and phubbing behavior among Flemish adolescents.,(10), Article 2319.https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15102319

*Fuster, H., Chamarro, A., & Oberst, U. (2017). Fear of Missing Out, online social networking and mobile phone addiction: A latent profile approach.,(1), 22–30.

*Gao, X. (2019).(Unpublished master's thesis). Central China Normal University, Wuhan.

[高霞. (2019).(硕士学位论文). 华中师范大学, 武汉.]

*Gezgin, D. M. (2018). Understanding patterns for smartphone addiction: Age, sleep duration, social network use and fear of missing out.,(2), 166–177.

Gignac, G. E., & Szodorai, E. T. (2016). Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers.,, 74–78.

He, X. C., Guo, Y., He, X., & Feng, G. J. (2019). Meta- analysis review on the gender differences of Chinese teenagers' regulatory emotional self-efficacy.(8), 44–47.

[何相材, 郭英, 何翔, 冯观健. (2019). 中国青少年情绪调节自我效能感性别差异的元分析., (8), 44–47.]

Houghton, S., Lawrence, D., Hunter, S. C., Rosenberg, M., Zadow, C., Wood, L., & Shilton, T. (2018). Reciprocal relationships between trajectories of depressive symptoms and screen media use during adolescence.,(11), 2453–2467.

*Hu, G. Y. (2020).(Unpublished master's thesis). Jiangxi Normal University, Nanchang, China.

[胡光友. (2020).(硕士学位论文). 江西师范大学, 南昌.]

Huang, C. (2017). Time spent on social network sites and psychological well-being: A meta-analysis.(6), 346–354.

Huang, Z. H., Jing, Y. M., Yu, F., Gu, R. L., Zhou, X. Y., Zhang, J. X., & Cai, H. J. (2018). Increasing individualism and decreasing collectivism? Cultural and psychological change around the globe.(11), 2068–2080.

[黄梓航, 敬一鸣, 喻丰, 古若雷, 周欣悦, 张建新, 蔡华俭. (2018). 个人主义上升, 集体主义式微?——全球文化变迁与民众心理变化.(11), 2068–2080.]

Huedo-Medina, T. B., Sánchez-Meca, J., Marín-Martínez, F., & Botella, J. (2006). Assessing heterogeneity in meta- analysis: Q statistic or I2 index?(2), 193–206.

*Huguenel, B. M. (2017).(Unpublished master's thesis). Loyola University.

Hunt, M. G., Marx, R., Lipson, C., & Young, J. (2018). No more FOMO: Limiting social media decreases loneliness and depression.(10), 751–768.

Hunter, J. E., & Schmidt, F. L. (2004).(2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Jagtiani, M. R., Kelly, Y., Fancourt, D., Shelton, N., & Scholes, S. (2019). State Of Mind: Family meal frequency moderates the association between time on social networking sites and well-being among U.K. young adults.(12), 753–760.

*Jiang, Y. Z., & Jin, T. L. (2018). The relationship between adolescents' narcissistic personality and their use of problematic mobile social networks: The effects of fear of missing out and positive self-presentation.(11), 64–70.

[姜永志, 金童林. (2018). 自恋人格与青少年问题性移动社交网络使用的关系: 遗漏焦虑和积极自我呈现的作用., (11), 64–70.]

Keles, B., McCrae, N., & Grealish, A. (2020). A systematic review: The influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents.(1), 79–93.

*Lai, C., Altavilla, D., Ronconi, A., & Aceto, P. (2016). Fear of missing out (FOMO) is associated with activation of the right middle temporal gyrus during inclusion social cue.,, 516–521.

*Lee, K. H., Lin, C. Y., Tsao, J., & Hsieh, L. F. (2020). Cross-sectional study on relationships among FoMO, social influence, positive outcome expectancy, refusal self-efficacy and SNS usage.,(16), Article 5907. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165907

*Li, J. (2020).(Unpublished master's thesis). Henan University, Kaifeng, China.

[李静. (2020).(硕士学位论文). 河南大学, 开封]

Li, J. Y., & Ma, L. (2019). The effect of the passive use of social networking sites on college students' fear of missing out: The role of perceived stress and optimism.(4), 949–955.

[李巾英, 马林. (2019). 被动性社交网站使用与错失焦虑症: 压力知觉的中介与乐观的调节.(4), 949–955.]

*Li, L., Griffiths, M. D., Niu, Z., & Mei, S. (2020). The Trait-State fear of missing out scale: Validity, reliability, and measurement invariance in a Chinese sample of university students., 711–718.

*Li, Q., Wang, J. N., Zhao, S. Q., & Jia, Y. R. (2019a). Validity and reliability of the Chinese version of the fear of missing out scale in college students.(4), 312–317.

[李琦, 王佳宁, 赵思琦, 贾彦茹. (2019a). 错失焦虑量表测评大学生的效度和信度.,(4), 312–317.]

*Li, Q., Wang, J. N., Zhao, S. Q., & Jia, Y. R. (2019b). The effect of basic psychological needs on college students' fear of missing out and the passive use of social networking sites.(7), 1088–1090.

[李琦, 王佳宁, 赵思琦, 贾彦茹. (2019b). 基本心理需要对大学生错失焦虑和被动性社交网站使用的影响.,(7), 1088–1090.]

Light, R. J., & Pillemer, D. B. (1984).. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

*Liu, C., & Ma, J. L. (2020). Social support through online social networking sites and addiction among college students: The mediating roles of fear of missing out and problematic smartphone use., 1892–1899.

Liu, D., Ainsworth, S. E., & Baumeister, R. F. (2016). A meta-analysis of social networking online and social capital.(4), 369–391.

Liu, D., & Baumeister, R. F. (2016). Social networking online and personality of self-worth: A meta-analysis.,, 79–89.

Liu, D., Baumeister, R. F., Yang, C. C., & Hu, B. (2019). Digital communication media use and psychological well- being: A meta-analysis.(5), 259–273.

Liu, Z. J., Kong, F. C., Zhao, G., Wang, Y. D., Zhou, B., & Zhang, X. J. (2018). The association between social network sites use and depression: A meta-analysis.(6), 60–66+91.

[刘诏君, 孔繁昌, 赵改, 王亚丹, 周博, 张星杰. (2018). 抑郁与社交网站使用的关系: 来自元分析的证据.(6), 60–66+91.]

*Ma, J. L., & Liu, C. (2019). The effect of fear of missing out on social networking sites addiction among college students: The mediating roles of social networking site integration use and social support.(5), 605–614.

[马建苓, 刘畅. (2019). 错失恐惧对大学生社交网络成瘾的影响: 社交网络整合性使用与社交网络支持的中介作用.,(5), 605–614.]

Marengo, D., Longobardi, C., Fabris, M. A., & Settanni, M. (2018). Highly-visual social media and internalizing symptoms in adolescence: The mediating role of body image concerns.,, 63–69.

Mieczkowski, H., Lee, A. Y., & Hancock, J. T. (2020). Priming effects of social media use scales on well-being outcomes: The influence of intensity and addiction scales on self- reported depression.. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120961784

Milyavskaya, M., Saffran, M., Hope, N., & Koestner, R. (2018). Fear of missing out: Prevalence, dynamics, and consequences of experiencing FOMO.,(5), 725–737.

Monacis, L., de Palo, V., Griffiths, M. D., & Sinatra, M. (2017). Social networking addiction, attachment style, and validation of the Italian version of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale.,(2), 178–186.

*Moore, K., & Craciun, G. (2020). Fear of missing out and personality as predictors of social networking sites usage: The Instagram case..Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294120936184

*Müller, S. M., Wegmann, E., Stolze, D., & Brand, M. (2020). Maximizing social outcomes? Social zapping and fear of missing out mediate the effects of maximization and procrastination on problematic social networks use..Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106296

*Munawaroh, E., Nurmalasari, Y., & Sofyan, A. (2019). Social network sites usage and fear of missing out among female Instagram user., 140–142.

*Öztürk, H., Gençoğlu, İ., & Kırkgöz, F. (2020). The Relationship between type of social media usage and depression with fear of missing out.,, 1–10

*Perrone, M. A. (2016).(Unpublished doctoral dissertation).Alfred University.

Peterson, R. A., & Brown, S. P. (2005). On the use of beta coefficients in meta-analysis.(1), 175–181.

*Pontes, H. M., Taylor, M., & Stavropoulos, V. (2018). Beyond “Facebook addiction”: The role of cognitive- related factors and psychiatric distress in social networking site addiction.,(4), 240–247.

Przybylski, A. K., & Weinstein, N. (2017). A large-scale test of the goldilocks hypothesis: Quantifying the relations between digital-screen use and the mental well-being of adolescents.(2), 204–215.

*Przybylski, A. K., Murayama, K., DeHaan, C. R., & Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out.,(4), 1841–1848.

Rasmussen, E. E., Punyanunt-Carter, N., LaFreniere, J. R., Norman, M. S., & Kimball, T. G. (2020). The serially mediated relationship between emerging adults’ social media use and mental well-being.,, 206–213.

*Reer, F., Tang, W. Y., & Quandt, T. (2019). Psychosocial well-being and social media engagement: The mediating roles of social comparison orientation and fear of missing out.,(7), 1486–1505.

*Ren, J. (2019).(Unpublished master's thesis). Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou, China.

[任静. (2019).(硕士学位论文). 西北师范大学, 兰州.]

*Reyes, M. E. S., Marasigan, J. P., Gonzales, H. J. Q., Hernandez, K. L. M., Medios, M. A. O., & Cayubit, R. F. O. (2018). Fear of missing out and its link with social media and problematic internet use among Filipinos.,(3), 503–518.

Richard, F. D., Bond Jr, C. F., & Stokes-Zoota, J. J. (2003). One hundred years of social psychology quantitatively described.,(4), 331–363.

*Riordan, B. C., Cody, L., Flett, J. A., Conner, T. S., Hunter, J., & Scarf, D. (2020). The development of a single item FoMO (fear of missing out) scale.1215–1220.

*Rogers, A. P., & Barber, L. K. (2019). Addressing FoMO and telepressure among university students: Could a technology intervention help with social media use and sleep disruption?,, 192–199.

Rothstein, H. R., Sutton, A. J., & Borenstein, M. (2005).. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Royal Society for Public Health. (2017). #Status of mind: Social media and young people’s mental health and wellbeing. Retrieved December 1, 2020, from https:// www.rsph.org.uk/our-work/campaigns/status-of-mind.html

*Rozgonjuk, D., Sindermann, C., Elhai, J. D., & Montag, C. (2020). Fear of missing out (FoMO) and social media’s impact on daily-life and productivity at work: Do WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram and Snapchat use disorders mediate that association?. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. addbeh.2020.106487

Saiphoo, A. N., Halevi, L. D., & Vahedi, Z. (2020). Social networking site use and self-esteem: A meta-analytic review..Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.109639

Schmidt, F. L., Oh, I. S., & Hayes, T. L. (2009). Fixed-versus random-effects models in meta-analysis: Model properties and an empirical comparison of differences in results.,(1), 97–128.

*Scott, H., & Woods, H. C. (2018). Fear of missing out and sleep: Cognitive behavioural factors in adolescents' nighttime social media use.,, 61–65.

*Sharma, S. (2015).(Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Mississippi State University.

*Sheldon, P., Antony, M. G., & Sykes, B. (2020). Predictors of problematic social media use: Personality and life-position indicators.. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294120934706

Shensa, A., Sidani, J. E., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Switzer, G. E., Primack, B. A., & Choukas-Bradley, S. (2020). Emotional support from social media and face-to-face relationships: Associations with depression risk among young adults.38–44.

Slater, M. D. (2007). Reinforcing spirals: The mutual influence of media selectivity and media effects and their impact on individual behavior and social identity.(3), 281–303.

Song, H., Zmyslinski-Seelig, A., Kim, J., Drent, A., Victor, A., Omori, K., & Allen, M. (2014). Does Facebook make you lonely? A meta-analysis., 446–452.

Song, X. K., Zhao, Y. X., & Zhang, X. H. (2017). Developing a fear of missing out (FoMO) measurement scale in the mobile social media environment.(11), 96–105.

[宋小康, 赵宇翔, 张轩慧. (2017). 移动社交媒体环境下用户错失焦虑症(FoMO) 量表构建研究.(11), 96–105.]

*Stead, H., & Bibby, P. A. (2017). Personality, fear of missing out and problematic internet use and their relationship to subjective well-being.,, 534–540.

Thorisdottir, I. E., Sigurvinsdottir, R., Asgeirsdottir, B. B., Allegrante, J. P., & Sigfusdottir, I. D. (2019). Active and passive social media use and symptoms of anxiety and depressed mood among Icelandic adolescents.(8), 535–542.

Tokunaga, R. S. (2017). A meta-analysis of the relationships between psychosocial problems and internet habits: Synthesizing internet addiction, problematic internet use, and deficient self-regulation research.(4), 423–446.

*Tomczyk, Ł., & Selmanagic-Lizde, E. (2018). Fear of Missing Out (FOMO) among youth in Bosnia and Herzegovina—scale and selected mechanisms.,, 541–549.

*Traş, Z., & Öztemel, K. (2019). Examining the relationships between facebook intensity, fear of missing out, and smartphone addiction.(1), 91–113.

*Tunc-Aksan, A., & Akbay, S. E. (2019). Smartphone addiction, fear of missing out, and perceived competence as predictors of social media addiction of adolescents.,(2), 559–566.

Twenge, J. M., Joiner, T. E., Rogers, M. L., & Martin, G. N. (2018). Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among US adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time.(1), 3–17.

Vahedi, Z., & Zannella, L. (2019). The association between self-reported depressive symptoms and the use of social networking sites (SNS): A meta-analysis.. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s12144-019-0150-6

Valkenburg, P. M., Peter, J., & Walther, J. B. (2016). Media effects: Theory and research.(1), 315–338.

*Vallejos-Flores, M. Á., Copez-Lonzoy, A. J. E., & Capa-Luque, W. (2018). Is there anyone online? Validity and reliability of the Spanish version of the Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (BFAS) in university students.,(2), 175–184.

*Wang, M. Y., Yin, Z. Z., Xu, Q., & Niu, G. F. (2020). The relationship between shyness and adolescents’ social network sites addiction: Moderated mediation model.(5), 906–909+ 914.

[王梦云, 尹忠泽, 徐泉, 牛更枫. (2020). 羞怯与青少年社交网站成瘾的关系:有调节的中介模型.(5), 906–909+914.]

*Wegmann, E., Oberst, U., Stodt, B., & Brand, M. (2017). Online-specific fear of missing out and Internet-use expectancies contribute to symptoms of Internet- communication disorder.,, 33–42.

*Wei, Q. (2018).(Unpublished master's thesis). Central China Normal University, Wuhan.

[魏祺. (2018).(硕士学位论文). 华中师范大学, 武汉.]

Wu, Y., Wu, L., Niu, G. F., Chen, Z. Z., & Liu, L. Z. (2020). The influence of WeChat moments use on undergraduates' depression: The effects of negative social comparison and self-concept clarity.(4), 486–493.

[吴漾, 武俐, 牛更枫, 陈真珍, 刘丽中. (2020). 微信朋友圈使用对大学生抑郁的影响: 负面社会比较和自我概念清晰性的作用.,(4), 486–493.]

*Xiao, M. M., & Liu, A. S. (2019). Revision of the Chinese version of trait-state fear of missing out scale.,2), 268–272.

[肖曼曼, 刘爱书. (2019). 特质——状态错失恐惧量表的中文版修订.2), 268–272.]

*Yin, L. P., Wang, P. C., Nie, J., Guo, J. J., Feng, J. M., & Lei, L. (2019). Social networking sites addiction and FoMO: The mediating role of envy and the moderating role of need to belong.. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00344-4

Yin, X. Q., de Vries, D. A., Gentile, D. A., & Wang, J. L. (2019). Cultural background and measurement of usage moderate the association between social networking sites (SNSs) usage and mental health: A meta-analysis.,(5), 631–648.

Yu, G. L. & Zhang, Y. L. (2020). The integration of mental health education for preschoolers to college students: From the perspective of personality.(6), 125–133.

[俞国良, 张亚利. (2020). 大中小幼心理健康教育一体化: 人格的视角.,(6), 125–133.]

Zhang, Y. L., Li, S., & Yu, G. L. (2019). The relationship between self-esteem and social anxiety: A meta-analysis with Chinese students.(6), 1005–1018.

[张亚利, 李森, 俞国良. (2019). 自尊与社交焦虑的关系: 基于中国学生群体的元分析.(6), 1005–1018.]

*Zhang, Y. L., Li, S., & Yu, G, L. (2020). Fear of missing out and cognitive failures in college students: Mediation effect of mobile phone social media dependence.(1), 67–70+81.

[张亚利, 李森, 俞国良. (2020). 大学生错失焦虑与认知失败的关系: 手机社交媒体依赖的中介作用.(1), 67–70+81.]

*Zhang, Y. X., Jiang, W. J., Ding, Q., & Hong, M. F. (2019). Social comparison orientation and social network sites addiction in college students: The mediating role of fear of missing out.(5), 928–936.

[张永欣, 姜文君, 丁倩, 洪梦飞. (2019). 社会比较倾向与大学生社交网站成瘾: 错失恐惧的中介作用.,(5), 928–936.]

*Zhang, Z., Jiménez, F. R., & Cicala, J. E. (2020). Fear of missing out scale: A self‐concept perspective.(11), 1619–1634.

The relationship between social media use and fear of missing out: A meta-analysis

ZHANG Yali, LI Sen, YU Guoliang

(School of Education, Renmin University of China, Beijing, 100872, China) (Institute of Psychology, Renmin University of China, Beijing, 100872, China)

Social media use and fear of missing out are both common phenomena in our daily life. Numerous studies have discussed the relationship between these two variables, but the results were mixed. Theoretically, there are two main arguments about the relationship between social media use and fear of missing out. To be specific, the social cognitive theory of mass communication suggested that there was a significant positive correlation between the two variables, while the digital goldilocks hypothesis argued that there may be a U-shaped relationship instead of a significant linear correlation between the two. Empirically, the effect sizes of this relationship reported in the existing literature were far from consistent, with r values ranging from 0 to 0.75. Therefore, this meta-analysis was conducted to explore the strength and moderators of the relationship between social media use and fear of missing out.

Through literature retrieval, 65 studies consisting of 70 independent effect sizes that met the inclusion criteria were selected. In addition, a random-effects model was selected to conduct the meta-analysis in Comprehensive Meta-Analysis 3.3 software, aiming at testing our hypotheses. The heterogeneity test illustrated that there was significant heterogeneity among 70 independent effect sizes, indicating that the random-effects model was appropriate for subsequent meta-analyses. Based on the funnel plot and Egger’s test of regression to the intercept, no significant publication bias was found in the included studies.

The main effect analysis indicated a significant positive correlation between social media use and fear of missing out (= 0.38). The moderation analyses revealed that the relationship between social media use and fear of missing out was moderated by the indicator of social media use, as well as the type of social media. Specifically, compared with the frequency, the time as well as the intensity of social media use, social media use addiction had the strongest correlation with fear of missing out; compared with Snapchat and Facebook, Instagram had the strongest correlation with fear of missing out. Other moderators such as gender, age, measurement tools of fear of missing out as well as individualism index did not moderate the relation between these two constructs. The results supported the media effect model, which suggested that social media use, especially social media use addiction may be an important risk factor for individuals’ fear of missing out. Longitudinal studies are needed in the future to explore the dynamic relationship between social media use and fear of missing out.

fear of missing out, social media, social networking sites, meta-analysis

2020-08-11

* 中国人民大学2019年度拔尖创新人才培育资助计划成果。

俞国良, E-mail: yugllxl@sina.com

B849: C91