特拉尼的但丁纪念堂:一场穿越历史、现代与但丁作品的旅途

2021-03-02伊拉里亚贝尔纳迪IlariaBernardi

伊拉里亚·贝尔纳迪/Ilaria Bernardi

黄华青 译/Translated by HUANG Huaqing

1 项目介绍

为了理解这个项目的复杂性及其多重概念层次,有必要先介绍建筑师朱塞佩·特拉尼,以及项目的主要对象:但丁及其创作于14世纪初的文学杰作——《神曲》。

朱塞佩·特拉尼(1904-1943)是意大利理性主义建筑的创始者之一,他的其他主要建筑作品还包括科莫市的“法西斯宫”这一20世纪意大利最知名的建筑。他近40年的人生与当时建筑界的重大事件紧密交织,他也是这些事件坚定的拥护者。

特拉尼毕业于米兰理工大学建筑系。1926年,他在大学期间便与志同道合的路易吉·费基尼、季诺·波里尼、卡罗·拉瓦、塞巴斯蒂亚诺·拉科等人创立了“七人组”;此后,另一位重要人物阿达尔贝托·里贝拉受邀加入。“七人组”反对当时的设计潮流,在1926-1927年发表了一篇“宣言”,要求改革意大利建筑,并将其命名为“理性主义建筑”。同时,特拉尼在家乡科莫从事建筑实践,通过与当地客户及职业圈的联系,得到一些重要的项目委托。他的早期作品中,值得一提的是“新科莫”住宅楼(科莫,1927-1929),采用现代技术建造(包括混凝土结构及悬挑楼板),因而也被认为是意大利理性主义建筑的第一个建成作品;还有维特鲁姆商店(科莫,1930),该项目标志着他开始采取基于抽象主义的设计路径——特拉尼是这一现代艺术运动的追随者。在他的身边,可以找到当时意大利文学和艺术文化圈的领袖人物,包括作家M·伯坦佩里,后者也协助他完成了但丁文学作品的分析。

1932年,特拉尼在米兰开业,合伙人是绘图教授P·林杰里(1894-1968),他生于科莫附近的特雷梅佐。他们的合作始于几年前的项目“烈士纪念碑”(科莫,1925)。林杰里并未直接参与特拉尼和“七人组”的运动,但他有着共同的改革理想:1931年,他被任命为意大利理性主义建筑运动的科莫总秘书。

通过米兰的事务所,他们完成了5项住宅楼项目;这些项目帮助他们结识并熟悉了米兰的客户,由此也获得一些政府委托——其中就包括1938年的但丁纪念堂。

2 项目之始

1938年,里诺·瓦尔达梅里——米兰布雷拉美术学院校长、但丁《神曲》其中一个重要版本的策划者——和亚历山德罗·伯斯一起促成了在罗马建造但丁纪念堂的计划。他们委托特拉尼和林杰里进行设计,后者因其布雷拉美术学院新馆的设计方案而知名。11月10日,方案被呈递给墨索里尼本人,他认可了整体方案。但在项目深化阶段,恰赶上1939年第二次世界大战爆发。特拉尼应征入伍,成为一名炮兵队长,只能通过信件跟进项目。林杰里接管了设计,继续与业主及政府官员沟通。原本项目计划在1942年完工,但到1940年时,原本应该敲定项目的会议,因欧洲战事的蔓延被推迟了。同年,瓦尔达梅里去世,意大利法西斯政府加大战争投入,原先的项目资金被挪用于军事开销,这直接暂停了设计进程。特拉尼本人也在1943年去世,当时他刚从德意联军赴俄国的灾难性出征中归来。

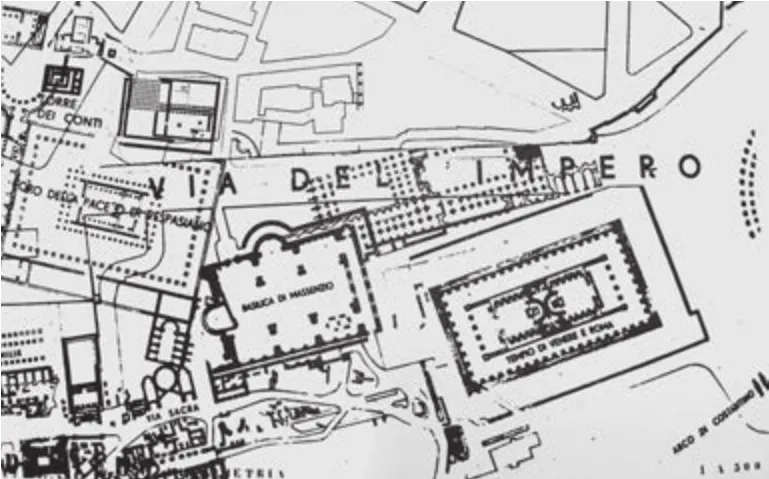

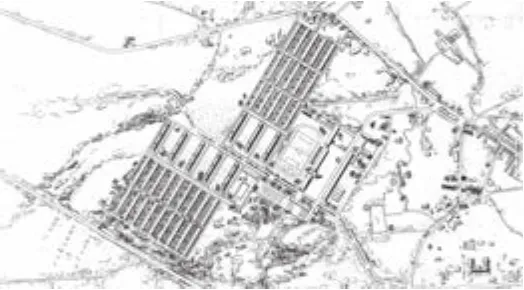

但丁纪念堂的构想是作为一处致力于但丁研究的中心。它的选址位于新近完工的罗马帝国大道(1932),这条大道将伊曼努埃尔二世纪念碑与古斗兽场相连,更加激进地渲染出当代法西斯政权沿袭于古罗马帝国的浪漫想象。在这条大道修建期间,古罗马的马克森提乌斯巴西利卡出土,若但丁纪念堂建成,它将正对这座巴西利卡(图1)。

这座建筑包括一座博物馆和一座图书馆,后者用于收集但丁作品的各种版本。特拉尼将这座建筑转变为一个充满隐喻的空间:3个主要厅堂分别代表《神曲》的3部分——地狱、炼狱和天堂;此外还有百柱厅(“百”代表了神曲的一百章)、帝国大厅和图书室,它们皆由一条空中步道相连,隐喻着《神曲》所描述的旅程。

3 主题:但丁的《神曲》

《神曲》是意大利语的奠基石,它是第一部由意大利语取代拉丁语写成的诗作,无疑是意大利文学史上的巅峰诗作。由于但丁是这个项目的核心对象,《神曲》也自然被特拉尼视为但丁纪念堂内涵的主要灵感来源。

《神曲》作于1301-1327年,以诗歌形式讲述了但丁穿梭于3个世界的旅程:“地狱”(受诅咒灵魂的居所)、“炼狱”(赎罪灵魂的居所)和“天堂”(上帝之光普照的圣灵居所)。

1 特拉尼和林杰里绘制的用地规划。但丁纪念堂位于左上部,马克森提乌斯巴西利卡位于中下部/Urban plan of the location by Terragni and Lingeri. Danteum is on left top part,Basilica of Maxentius on centre bottom(图片来源/Source:参考文献[5]40/References [5]40)

1 Project Introduction

In order to understand the complexity of the project and its many conceptual layers, it is necessary an introduction of the architect Giuseppe Terragni, and of the project main subject: Dante Alighieri and his literary masterpieceDivine Comedy, written in the beginning of the 14th century.

Giuseppe Terragni (1904-1943) stands as one of the founders of Italian Rationalist Architecture, and is the architect who brought to completion, among other projects, the "Casa del Fascio" in Como, the most renowned Italian built architecture of the 20th century. His nearly 40-year life was intertwined with the most important happenings and events on the architecture field of his times, of which he became an affirmed protagonist.

Graduated in Architecture at Polytechnic University of Milan, since his university studies he shared ideas with Luigi Figini, Gino Pollini, Carlo Rava and Sebastiano Larco, together with whom he founds the "Gruppo 7" (Group 7) in 1926; to this group was invited to join the equally important figure of Adalberto Libera. In opposition to the design trend of his period, Group 7 published in 1926-1927 a "manifesto" for the reform of the Italian architecture, renaming it Rationalist Architecture.Besides, Terragni carried on his professional activity in Como, his hometown, receiving important assignments through connections with local clients and professionals. Among his first works, to be highlighted the residential building "Novocomum"(Como, 1927-1929), built with modern techniques(concrete structure and cantilevered floors) and therefore considered the first completed project of the Italian Rationalist architecture; and the Vitrum shop (Como, 1930), marking the start of a design approach centred on Abstractism, a contemporary art movement followed by Terragni. Around him, we find leading figures of the Italian literary and artistic cultural scene, among which writer M. Bontempelli.The latter was supporting the architect on the analysis of Dante's artwork.

On 1932 he started his office in Milan with P. Lingeri (1894-1968), professor of drawing technique, born at Tremezzo near Como. The collaboration between them begun some years earlier by the project "Monumento dei Caduti"( Monument to the fallen soldiers, Como, 1925).Lingeri is not directly involved in the campaign by Terragni and Group 7, but he shares their reform intentions: in 1931 he was named secretary in Como of the MIAR - Italian Rationalist Architecture Movement.

By their Milan office, they complete five apartment buildings; these projects allow them to be affirmed, to know Milan clients and to be known,and finally to receive governmental assignments,among which the Danteum project in 1938.

2 Starting of the Project

In 1938 Rino Valdameri, director of Brera Academy of Fine Arts in Milan and curator of one important edition of Dante'sDivine Comedy,promotes with Alessandro Poss the construction of Danteum in Rome. They call for the design G. Terragni and P. Lingeri, known for their proposal of the new Brera Academy building. On November 10th the project is shown to Mussolini himself,who approves the general plan. But during the next phase of the project, at the outburst of World War II in 1939, Terragni is called on to military duty as artillery captain and could follow the project only by mail. Lingeri takes charge of the design process,dealing with clients and government authority.The completion is set for 1942, but already in 1940 the meetings to define the project are suspended,because of the spreading warfare in Europe. In the same year Valdameri would pass away, Italian fascist government takes active part in the conflict, and the funds for the project are diverted to military expenses, definitely stopping the design process.Terragni himself would pass away in 1943, after returning from the disastrous German-Italian expedition in Russia.

Danteum was proposed to be a centre for the studies dedicated to Dante Alighieri. It was to be built in Rome along the recently completed"Via dei Fori Imperiali" (1932), a road laid out to link the "King Victor Emanuel II Monument"with "Coliseum", and therefore to enhance the propaganda of a continuous romanity from the Roman Empire directly to the contemporary fascist regime. During the avenue construction, the ancient roman "Basilica of Maxentius" had been entirely dug up: the Danteum should have appeared exactly in front of the Basilica (Fig. 1).

The programme consisted of a museum and a library to gather the many editions of Dante's opera. Terragni transforms the building in a space of metaphors: the three main rooms represent the three parts of theDivine Comedy- Inferno,Purgatory and Paradise; to these he adds up the 100-columns hall (one hundred like the chapters of the Comedy), the hall of the Empire and the Library room, connected by a raising pathway, metaphor of the journey described in theDivine Comedy.

3 Main Theme: Dante's Divine Comedy

Being the founding stone of the Italian language - the first literary poem written in Italian,replacing Latin language - theDivine Comedyis unanimously regarded as the highest poetry among the Italian literary production. Being Dante the subject of the project, theDivine Comedywas naturally taken by Terragni as the main source of inspiration for the Danteum's content.

Composed between 1301 and 1327, theDivine Comedytells in rhymes the journey undertaken by Dante through three worlds: Inferno (place of the damned souls), Purgatory (place for the souls in atonement of their sins), and Paradise (place for the saint souls in the light of God).

The journey through the three worlds is conceived as a precise architectural scheme: from bottom to top along the globe axis, it passes through the underworld, then raising up on a high mountain, ending up to the open sky. During the journey, Dante is led by Virgilio - one the highest poets of the Roman Empire - and at the final stage by Beatrice - a woman symbolising the spiritual love of God. In Dante's religious vision, this redemption path takes place both on spiritual and civic level.

As theDivine Comedyis intended as a metaphor of every man's path on Earth, Terragni's Danteum is to be considered the architectural tool through which the journey experience is made tangible.

穿越3个世界的旅程直接与建筑布局对应:从底层到顶层,沿着地球轴线,会依次穿过地下世界,而后升至一座高山,最后抵达开放的天空。这趟旅途中,但丁的领路人是维吉尔——罗马帝国最伟大的诗人之一,最后阶段则追随着贝阿特丽切——代表了上帝精神之爱的女子。在但丁的宗教观之中,救赎的道路需同时在精神和世俗层面展开。

由于《神曲》的目的是对每个人的世界旅途的隐喻,特拉尼的但丁纪念堂也就被作为一件让这趟旅途变得真实可触的建筑工具。

4 但丁纪念堂:项目解析

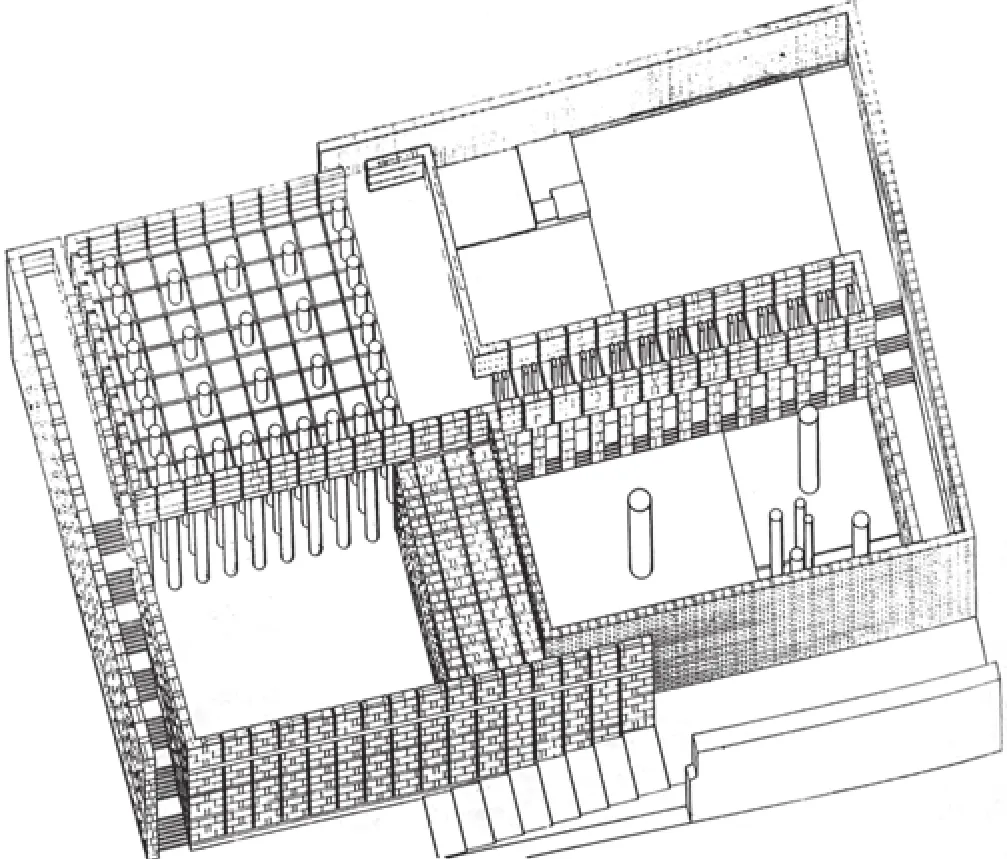

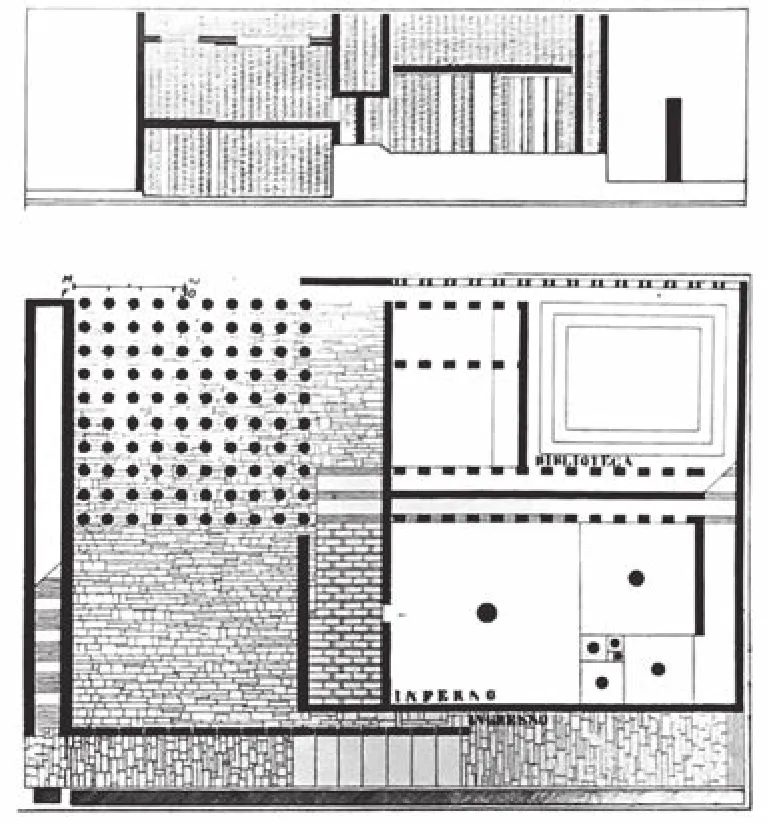

从外部看,这座建筑如同一座紧凑的方块,无法看到内部的不同楼层(图2、3)。矩形平面被分作4个部分,其中,左下角的是第一个方形露天庭院;这个宽阔的天井是观者从沿路的墙体背后步入建筑后,看到的第一个空间。天井旁就是百柱厅,也是这座建筑中第一个有顶的空间。

观者穿越错综复杂的百柱厅——这里隐喻了《神曲》最初的“黑暗森林”,接着进入地狱厅(图4)。厅内有7根不同尺寸的柱子,沿着7块不同大小、螺旋下降的地板排列;厅内几乎没有任何自然光,只在天顶有一条细细的采光缝隙。

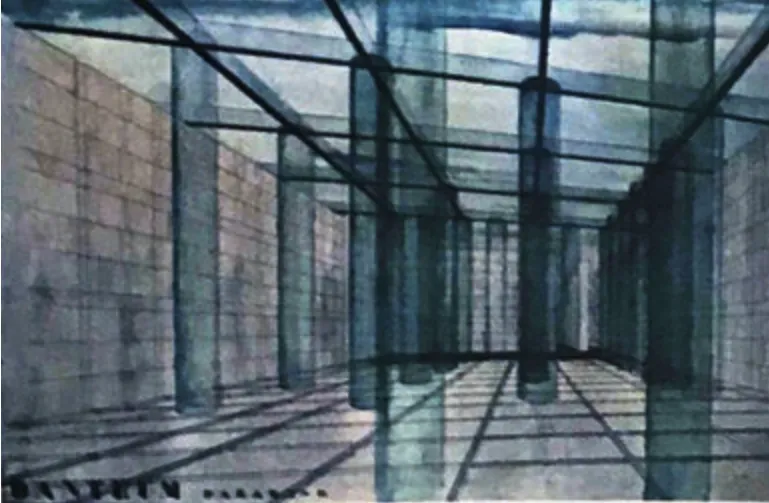

接着,沿路进入上层的炼狱厅(图5)。它的屋顶被分为7块逐步变大的方框,形成一系列天窗。天堂厅(图6)则位于百柱厅之上,厅内矗立33根玻璃柱,其上是面向天空开敞的网格钢梁。

参观路线的最后是狭长的帝国厅(图7),它是前述诸个厅堂间的过渡空间,也是建筑旅途的终结。图书馆位于炼狱厅之下,第一个天井是唯一可由外部进入的空间。最后,观者将穿过一条狭长的走道,从入口的另一侧离开建筑。

3个主要厅堂位于不同楼层,并由沿外墙上升的狭窄台阶相连,这让观者可以不经重复地顺序参观各个展厅(图8-10)。这座建筑被构思为“一个分流机制和一种空间安排,它让博物馆成为一条连续的旅程:这在当时是个很罕见的理念,勒·柯布西耶本人在战后看到这个项目的模型时,一定也意识到它与他的理念相契合之处,及其本身独特的原创性。”[1]

穿越建筑的路线感知随着每个厅堂递增的亮度而增强:这是特拉尼用来建立但丁纪念堂的参观旅程与但丁《神曲》间的相似性最为敏锐的手法。自然光成为他主要的建筑设计工具,辅以混凝土和钢等现代建筑材料,不过在外立面都覆盖了石灰石挂板。玻璃是唯一一种以其纯粹、明亮的通透感呈现的材料,用于天堂厅的柱子。

5 遗存文献及评论中但丁纪念堂的意义

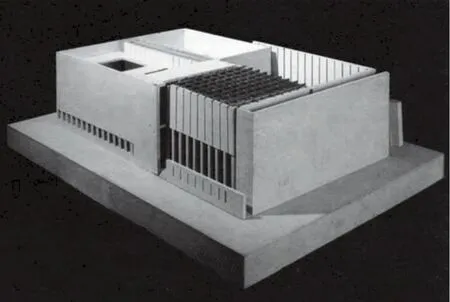

本文所展示的图纸属于少数留存至今的文献资料。这些是特拉尼和林杰里为向墨索里尼汇报而制作的正式图纸,包括厅堂的透视图,入口侧墙上由马里奥·希罗尼设计的浮雕效果图,还有一些模型照片(图11、12)。草案都在1944年米兰空袭期间,随着林杰里工作室一同被焚毁。初期的设计草图大部分出自特拉尼之手,后来在他的科莫工作室中找到,但亦不能完整呈现设计的发展过程。

此外还有两份报告,一份是理论报告,一份是技术报告,是在1938年正式汇报后由建筑师撰写的,旨在为拖延的设计进程提供动力。

2 百柱厅、3个主厅与帝国厅轴测/Axonometric view with the 100-column hall, the three main halls, and the hall of Empire

3 看向古斗兽场方向的透视/Perspective view towards the Coliseum(2.3 图片来源/Sources: ZEVI B. Omaggio a Terragni, published in L'architettura cronache e storia 153, July 1968: 248.)

4 地狱厅透视/Hall of the Inferno, perspective view

5 炼狱厅透视/Hall of the Purgatory, perspective view

6 天堂厅透视/Hall of the Paradise, perspective view(4-6 图片来源/Sources: 参考文献[4]49/References [4]49)

7 帝国厅透视/Hall of the Empire, perspective view(图片来源/Source: 参考文献[4]49/References [4]49)

4 Danteum: Project Analysis

From the exterior, the building appears as a compact block, as the different floor levels of the interior are not visible (Fig. 2, 3). The rectangular floor plan is divided into four quarters, of which the first one on bottom left corner is a squared yard open to the sky; this wide patio is the first space met by the visitor after the entrance, behind a wall along the road. Next to the patio is the 100-columns hall,the first covered space of the building.

The visitor passes through the intricate 100-columns hall, metaphor of the initial "selva oscura" (dark forest), and from there he enters the room of the Inferno (Fig. 4). Here are seven columns of different sizes, laid along a descending spiral of seven fioor squares; there is almost total absence of natural light, only coming by thin gaps on the ceiling.

The path raises then to the upper level's Purgatory hall (Fig. 5). Its ceiling is divided into seven squared frames, progressively increasing sizes,resulting in a set of skylights open to the sky. The Paradise hall (Fig. 6) is placed above the 100-columns hall, and displays 33 columns in glass, concluded by a grid of steel beams directly to the open sky.

The path ends up in the long Empire hall (Fig. 7)that stands as filtering space between the rooms, and concludes the path through the building. The library,placed below the Purgatory hall, and the first patio are the only spaces accessible from outside. The visitor would finally exit through a narrow passage, coming out on the side of the entrance.

The position of the three main halls on different levels and their narrow connections by ascending steps along the perimetre walls, lead the visitor through the halls, without any overlapping path (Fig. 8-10). The building is conceived as "a distributive mechanism and a spatial organisation that make the museum an itinerary: a rather unusual idea at that time, and Le Corbusier himself must have realised the consonance with his own ideas, but its originality as well, when after the war time he saw the model of the project"[1].

The treading of the path through the building is enhanced by the gradually increasing luminosity of the rooms: this is the most incisive method by Terragni to establish the similitude between the journey of the Danteum visitor and that of Dante in theDivine Comedy. Natural light becomes one of the main architectural design tools, accompanied by modern construction materials as concrete and steel, although here they are clad with travertine slabs. Glass is instead the only material to be displayed in its sheer shiny transparency on the columns of Paradise room.

5 Meanings of Danteum by Surviving Documents and Critics Review

The drawings displayed with this article are some of the few documents still remaining today.These are the official drawings by Terragni and Lingeri for the presentation to Mussolini, including perspectives of the rooms and a representation of the sculptures relief by Mario Sironi on the entrance wall, and some photographs of the model (Fig. 11,12). The unofficial documents were burnt by a fire in Lingeri's studio during the bombing of Milan in 1944. The preliminary sketches, attributed mostly to Terragni, were found in his studio in Como, but they do not consent a complete reading of the design development.

In addition, there are two reports, one theoretical and one technical, written by the architects after the 1938 presentation, to give impulse to the delayed project procedures.

Specifically, the theoretical report gives the author's indication on how to read the project.It explains the metaphoric correspondence between the Danteum and theDivine Comedy,correspondence consisting of geometric references,numbers, symbols, and space interpretation. As Terragni himself puts it: "this building can be de fined as polysemous"[2]; it has manifold meanings.

Such circumstances, as the scattered graphic documentation and the author's own explanation of the project metaphors, have led critics and researchers to analyse the correspondence between the architectural language and the text of the poem.

To summarise the many studies done in the past 70 years, we could gather them in three macrogroups. Between 1950 and 1970, the Danteum is first published on magazines. Between 1970 and 2000, appeared some critical interpretations of the project, in relation to Terragni's works and his complex design methods. From 2000 up to today,the digital reconstruction of the project proved the unprecedented spatial and typological innovation of the Danteum.

The commemorative exhibition on Terragni held in 1949 for the first time displayed the official drawings of the project, of which Le Corbusier sensed the originality. In 1968, in occasion of the congress organised by Bruno Zevi on Terragni's heritage, were published some unedited drawings and documents of the Danteum. Comments on the project were mixed and sometimes opposing. Zevi shares the position of Giulio C. Argan: the idea of interpreting the floor plan according to the poem structure was to them "a major mistake"; Argan also criticises the excessive rhetoric of the project for his"expressing in architecture the victory, motherland,the eternity of empire"[3]; but Zevi at the same time recognises its values, as "transgression of the classic rules, contrasts in the sequence of spaces,unbalanced relation with the context, volumetric disassembling, new glazed materials and lighting effects". Zevi acknowledges the Danteum as a lively building, for skillfully representing the poem's journey, and for introducing the visitor by emotional chords to its underlying signi ficance.

In 1976 Thomas L. Schumacher published a deepened research on Danteum[4]together with its watercolour drawings and model photographs.Analysing the plan and the building metaphors,he declares this project an icon in modern and international architecture history. Schumacher underlines that although the plan's proportions are derived from the roman Basilica of Maxentius,its two main squares are slightly shifted and overlapped, a recurrent operation in Terragni's design methods.

值得一提的是,这份理论报告包含了作者关于如何阅读这件作品的提示。它阐释了但丁纪念堂和《神曲》间的修辞对应关系,包括几何援引、数字、符号和空间诠释。如特拉尼所言:“这座建筑可以被认为是一词多义的”[2],它具有多层次的内涵。

这样的境遇——零乱的图纸资料和作者本人对建筑隐喻的阐释——吸引着评论家和研究者去分析建筑语言和诗歌词句之间的对应关系。

总结过去70年的诸多研究,我们可以将其归入3个阶段。1950-1970年,但丁纪念堂最早发表在期刊杂志;1970-2000年,出现了一些关于这个项目的评论文章,分析特拉尼的作品及其复杂的设计手法;2000年至今,项目的数字化复原证明了但丁纪念堂前所未有的空间和类型创新。

1949年举办的特拉尼纪念展,第一次展示了这个项目的官方图纸,勒·柯布西耶已从中察觉到项目的独创性。1968年,在布鲁诺·泽维组织的关于特拉尼遗产的会议上,但丁纪念堂的部分未经编辑的图纸和文献得以出版。关于这个项目的评论褒贬不一,有些甚至持反对意见。泽维也同意朱利奥·C·阿尔甘的观点:根据诗歌结构来诠释建筑平面的想法是个“大错”;阿尔甘还批评了这个项目的过度修辞化,因为他“在建筑中表达了胜利、祖国和帝国永恒的寓意”[3];不过,泽维同时认可了这个项目的价值,包括“对古典规则的打破,在空间序列上的反差,与文本的不均衡关系,体量的拆解,新的玻璃材料的运用及采光效果”。泽维认同但丁纪念堂是一栋生动的建筑作品,它巧妙再现了诗歌所描绘的旅程,并通过引发观者的情绪共鸣,来感受诗歌的潜藏意涵。

1976年,托马斯·L·舒马赫发表了一份但丁纪念堂的较深入研究[4],同时出版了它的水彩渲染和模型照片。他通过对建筑平面及其隐喻的分析,宣告这个项目是现代主义及国际建筑史上的标志作品。舒马赫发现,尽管它的建筑平面比例源于古罗马的马克森提乌斯巴西利卡,但它的两个主要方形微微偏移叠合,这是特拉尼设计方法中常出现的操作。

根据舒马赫的研究,有可能找到但丁纪念堂设计背后超越文本和隐喻的另一层意义。那就是它创造了一种独特的、前所未有的类型学,就像特拉尼自己在理论报告中所写:在这个设计中,博物馆、宫殿和剧场的类型汇聚为一种神庙的类型学,这种类型学指向精神的组成,能够将建筑作品提升到神秘的维度。

将但丁纪念堂阐释为神庙的观点,在2000年左右得到印证——乔吉奥·邱奇找到了这份报告的最初片段,命名为“但丁纪念堂的理论推演”[5]:特拉尼解释道,在这个项目中,现代建筑接受了直面纪念性和象征主义主题的挑战。因此,根据邱奇的论述,比起技术价值而言,特拉尼更倾心于建筑的诗意元素,因而设计了一栋神庙来提升它的艺术和精神价值。

另外,伊莉莎贝塔·特拉尼基于项目的建筑特征提出了另一种解释[6]:“围合建筑”(由环绕的墙体或柱廊围合中心的空间或体量)这种古老的类型学,很可能是特拉尼为但丁纪念堂选中的原型。实际上,当我们从这个角度来看待这栋建筑,对其空间的理解或许只需基于内部。特拉尼的设计遵从这一理念,从他很多的设计选择中皆可看出:全部位于室内的参观路线,没有开口的环墙,自然光仅从顶部进入建筑等等。

2015年,罗马第一大学组织了一场关于特拉尼在罗马的设计项目展览,其中就包括但丁纪念堂。在这场展览中,很多学者表达了各自观点。卢卡·利比奇尼认为[7],建筑的黄金分割矩形来自马克森提乌斯巴西利卡的比例,这显然印证了特拉尼将其建筑根植于这片考古区域的“场所精神”的意图;此外,还应研究他与意大利建筑传统的联系——从莱昂·巴蒂斯塔·阿尔伯蒂到20世纪的建筑师。

6 寻找项目之基

抛却作者报告中提出的那些悬而未决的问题,我们或许仍可探讨但丁纪念堂的某些隐含话题,部分也是特拉尼经常显现的设计意图:建筑本身的内涵;还有总体而言,现代建筑相对于历史及当代文脉的意义;建筑成为一种大众艺术的使命;最后,如何定义一种新的建筑类型学。

我们不难发现,这些话题从特拉尼的职业首秀开始便出现在他的个人研究之中——当他和“七人组”宣布创立全新的意大利理性主义建筑;同样的主题在这位年轻建筑师的推动下不断发展,形成了卓然超群的成果,即便在但丁纪念堂这样的晚期项目也是如此。

特拉尼的建筑作品实际上在两个固定基点之间游移:一边是来自国外现代主义建筑运动的显著影响,另一边他又坚信意大利理性主义建筑是独一无二的,这源于它的滥觞和文化传统。这样的立场,在1930年的一篇发表文章中得到公开的阐明,特拉尼和“七人组”一起宣告了意大利理性主义建筑相比于欧洲建筑运动的独特性[8]。

这一理念的核心认为,历史是一个可靠的基础,可在其上创建新建筑,让它在未来经受住时间的考验,而非一闪而过。

8 地狱厅剖面与1.60m标高平面/Section across the Hall of the Hell and plan +1.60m

9 百柱厅、炼狱厅与天堂厅剖面与6.00m标高平面/Section across the 100 columns hall and the halls of Purgatory and Paradise and plan +6.00m

10 庭院剖面与10.00m标高平面/Section across the courtyard and plan +10.00m(8-10 图片来源/Sources: MARCIANÒ A F. Giuseppe Terragni Opera Completa 1925-1943. Roma: Officina,1987: 218.)

这个项目与历史的关联,首先是通过对经典形式元素(如柱廊、墙、柱顶过梁)的建构及空间功能的复兴来实现的,这有赖于特拉尼深厚的建筑史知识。通过对古典纪念物——包括米开朗琪罗和文艺复兴的研究,特拉尼保持了古典构图的基本原则,但出于创立一种现代意大利建筑的想法,他剥离了所有不必要的装饰元素。

According to Schumacher, it is possible to find out one more meaning of the Danteum design,beyond the literal and metaphoric reading. That is the creation of a unique and unprecedented typology, as written by Terragni himself in the theoretical report:for this design, the museum, the palace and the theatre types merge into the typology of the temple,that opens up to the spiritual component, capable to raise the architecture work onto mystic level.

The interpretation of Danteum as a temple was con firmed around the year 2000, when Giorgio Ciucci finds out the initial fragment of the report, named then "Theoretical reason of the Danteum"[5]: Terragni explains that this is a project where the modern architecture undertakes the challenge of confronting with the themes of monumentality and symbolism.Therefore, according to G. Ciucci, Terragni favors the poetic element of the architecture over its technical values, and designs a temple to enhance its artistic and spiritual values.

On the other hand, Elisabetta Terragni offers yet a different interpretation, based on the architectural features of the project[6]: the ancient typology of the "fenced building" (perimetre walls or colonnade enclosing the core space or volume)is most probably the one that Terragni referred to for the Danteum. In fact, as the building is regarded this way, the understanding of its spaces is possible only by the inside. Terragni designed the building according to this idea, made evident by many of his design choices: the all-internal itinerary, the perimetre walls without openings, and natural light coming in only from the skylights.

Recently, in 2015, it was set up by the University Sapienza of Rome an exhibition dedicated to Terragni's projects in Rome, including the Danteum. In this occasion, many academics brought in their viewpoints. According to Luca Ribichini[7], the golden rectangle derived by the proportions of the Basilica of Maxentius evidently con firms Terragni's intention of rooting his building to the "Genius Loci" (the location's inspiring source)of the archeological area; in addition, it should be researched his connection with the Italian architectural tradition, from Leon Battista Alberti until 20th-century architects.

11 但丁纪念堂模型西南面外景,由马里奥·西罗尼制作的模型/Danteum model south-west view with the sculptured reliefs by Mario Sironi

12 但丁纪念堂模型北面外景/Danteum model north view(11.12 图片来源/Sources: MARCIANÒ A F. Giuseppe Terragni Opera Completa 1925-1943. Roma: Officina,1987.)

6 Searching the Project Foundation

Besides the still open questions posed by the author's report, it is possible to trace back some implicit topics of the Danteum, part of Terragni's recurring design intentions: the building's own signi ficance, and generally the meaning of a modern building in relation to the historic and the current context; the task of architecture in becoming art for the masses; and finally, the de finition of a new building typology.

It is possible to underline how these topics were already present in Terragni's personal research since his professional debut - when he together with Group 7 declared to be the founders of the new Italian Rationalist Architecture; and the same topics,being developed consistently by the young architect,gave out-of-ordinary, outstanding results, even on latest projects like the Danteum.

Terragni's architectural work moves in fact between two fixed points: the explicit reference to the foreign Modern Movement architecture, and the expressed conviction that Italian Rationalist Architecture was speci fic and different for its origins and cultural traditions. This position is openly declared in 1930, on a published article where Terragni with Group 7 claimed the peculiarity of Italian Rationalist Architecture compared to the European movement[8].

At the core of this idea is the conviction that history is a safe foundation to build on a new architecture, to be lasting, and not passing by, in future times.

The bond with history takes place, first of all, by the recovery of formal classical elements(such as columns, walls, architraves) with their constructive and spatial role, following Terragni's deep knowledge of architecture history. By studying the ancient monuments, as well as Michelangelo and the Renaissance, Terragni retains the general rules of composition, but according to his conviction of establishing a modern Italian architecture, rids of all the unnecessary ornaments.

As a matter of fact, one of the main issues brought by the upcoming Rationalist Architecture is the essential nature of the building, and the expressivity of its basic forms, to be displayed nude,without ornament.

The essential nature of Danteum is to be found in its pure figures and volumes (square, rectangle,parallelepiped) and its nude elements (walls,columns, beams and roofs); then, the expressivity is given by the dynamic composition of these elements: the shifting and breaking of the fioor-plan main rectangle, mentioned by Schumacher; and the complexity of the inner circulation, made of sudden shifts and turns through corridors and halls.

13 “新科莫”住宅楼与原有建筑的关系,东北面外景/Relationship between Novocomum and the existing building,north-east view(图片来源/Source: https://www.visitcomo.eu/export/sites/default/it/events/2016/allegati/FAICOMO-2016.pdf)

14 “新科莫”住宅楼北立面/Novocomum north elevation(图片来源/Source: CAVALLERI G, VITALE D, RODA A.Novocomum, Casa d'abitazione. Como: Nuove Parole, 1988:50-51.)

15 雷比奥卫星城轴测/Satellite city of Rebbio, axonometric view

16 雷比奥住宅楼与市中心的图书馆、市政大厅透视/Rebbio:residential buildings and city centre with library and city hall, perspective view(15.16 图片来源/Sources: PODESTÀ A. Progetto di un quartiere operaio, published in Costruzioni-Casabella, 158,1941: 35-36.)

由此而来的理性主义建筑的主要理念之一,就是坚持建筑的“基本性质”,坚持让其基本形式的表现性赤诚地呈现出来,不带任何装饰。

但丁纪念堂的基本性质可见于其纯粹的形式和体量(方形、矩形、平行六面体),及其裸露的建筑元素(墙、柱、梁、顶);然后,建筑的表现性是由这些元素的动态组合所塑造的:如舒马赫提到的,楼层平面中矩形主体的偏移和打断;还有复杂的室内流线组织,包括柱廊和厅堂之间突然的转折和转换。

另外,正如托马斯·舒马赫和卢卡·利比奇尼所强调的,特拉尼面向古典建筑史的姿态是直接对抗——在这个案例中,便是将新博物馆放置在古老的巴西利卡的正对面。由此,他得以在几何和比例层面建立起过去和现代建筑的直接对话。除了外墙的相似比例外,它还通过相反的特征形成一种对抗。尽管巴西利卡更大的体量由拱廊和半圆后殿雕琢而出,但丁纪念堂的沿街立面则是完全反转的:它所呈现的是一系列没有开洞的盲墙。无论如何,这两栋建筑将因其在城市环境中的存在而形成对话。

我们还可用另一处不同环境下的建筑举例,那就是“新科莫”住宅楼(特拉尼的早期作品之一,1927-1929年建于科莫,图13、14),这座建筑与场地南半部分的现存附楼间建立了一种修辞关联。“新科莫”住宅楼虽然维持了与现存建筑相同的比例,但它亦通过相反的特征来呈现出对抗姿态:方形转角对圆形转角,悬挑楼板对退台。

还值得一提的是,特拉尼的建筑语汇除了与历史的关联外,还试图与其同期的建筑学进展发生互动:欧洲的现代主义运动, 包括勒·柯布西耶、格罗皮乌斯、密斯·凡·德·罗;还有意大利的现代建筑师。在这样一个广阔的视角下, 出现了现代建筑的“功能”(欧洲建筑师不断强调)与其美学及精神价值(由意大利建筑界的探讨所提出)之间的理论对话。

特拉尼早在1928年就发现了这个问题。在“七人组”的论述中,他同时肯定了建筑的功能意义以及新意大利理性建筑的美学或“诗性”价值。不过,当重新阅读新发现的报告片段,特拉尼进一步提出了“大众艺术”这一问题,即认为艺术应该为整个民族的精神及审美诉求而服务。

在但丁纪念堂的案例中,由于它所处的地段紧邻遗址,但丁的诗歌又是一个极难呈现的对象,特拉尼知晓他所创造的建筑可能难免陷入“修辞化”的风险。因此,他的解决方式是在立面上使用一种温和简明的语言,剥除一切混乱的拱券、柱子或其它冗余元素(仅有入口墙面上希罗尼的巨幅浮雕);而在内部,他运用所有建筑学工具和手段来调动参观者的诗性感官。几年前,他曾使用这些词汇来阐释他的某个作品:“对我而言,观者能否理解这座纪念碑的寓意并不是决定性的;更重要的是它和观者之间建立的审美关联,以及被它所‘感动’的事实。”[9]

最后,但丁纪念堂提出的问题是,怎样的建筑类型学能够统合并完满回应所有这些设计要素,例如文学作品的再现、与历史及当下的关联、建筑的审美价值等。

特拉尼给出的答案,就是提供一种新建筑类型的基础。

如学界所认同的,但丁纪念堂构筑起一种前所未有的建筑类型学,而不是过往类型学的复制;它是研究,是创新,直面历史,忠于当下,并最终转译为建筑。

在此应再次提到,新建筑类型的基础就是“理性”建筑的概念,这早已在“七人组”的理论和作品中提出。实际上,同样的设计路径亦可见于另一座未建成建筑,是但丁纪念堂的同期作品:科莫附近的雷比奥居住街区,由特拉尼和阿尔贝托·萨托利斯于1938年设计(图15、16)。虽然项目的尺度、条件和功能目标截然不同,但这个城市项目的出发点就是创造多种不同的居住类型。这些创新类型不仅源于地理和社会条件,也来自对欧洲现存住宅建筑的深入研究。

7 结语

特拉尼的设计路径是在寻求新的建筑类型,这一事实让他的作品获得了独一无二的特质。即便在近100年之后,它们的独特性依然不断激起批评家和学者之间无休止的争论。

暂且不论那些关于特拉尼的设计意图的不同阐释,他独特的设计方法应该放在其职业及理论路径上去思考,并且放到它与意大利理性主义运动的理论和作品的共同发展之中来考虑。

但丁纪念堂无疑是现代建筑杰作中的一座里程碑。关于它的探求从未衰减,这源于它的未建成和无法复制的性质,它的特殊区位及挑战性话题,以及它对但丁作品的再现。我们甚至可以大胆地说,《神曲》和但丁纪念堂这两件作品,虽时隔遥远却深刻交缠,它们都是理解多层次的意大利文化的根基,尤其是在其各自特定的年代和背景。

时值纪念但丁逝世700周年,我们值得进一步探究文学和建筑的世界,以加深对这样一个迷人主题的理解——即不同艺术形式之间的关联。

Also, as highlighted by T. Schumacher and L.Ribichini, Terragni refers to classic history by direct confrontation, in this particular case by the position of the new museum in front of the ancient Basilica.He could then establish a correspondence between past and present architecture, in terms of geometry and proportions. But besides the perimetre's scaled proportions, it remains a confrontation by opposed features. While the bigger volume of the Basilica is carved by arches and by the round apse, the Danteum elevation on the avenue is plainly introverted: it displays a set of blind walls, without openings.Nevertheless, the two buildings would establish a dialogue by their urban presence on the avenue.

Although in a different context, we like to underline that also the residential building Novocomum (one of his first works, built at Como in 1927-1929, Fig. 13, 14) establishes a figurative relation with its side buildings, already built on the southern half of the same plot. The Novocomum,while maintaining the same dimensions of the existing building, undertakes the confrontation by displaying the opposed features: squared corners opposed to rounded corners, cantilevered floors opposed to recessed terraces.

It is convenient to mark that Terragni's architectural language, besides keeping up with history, aims to confront with its concurrent architectural developments: the European Modern Movement pioneered by Le Corbusier, Gropius,Mies Van der Rohe; and the Italian contemporary architects. In this larger scope it was already raised the theoretical dialectic between the "function" of the modern building (underlined many times by the European architects) and its esthetic and spiritual values (brought up in the Italian debate).

The problem was faced by Terragni already in 1928, when in Group 7's writings he defended both the functional aspect and the esthetic or "poetic"values of the new Italian Rationalist Architecture. But reading again the discovered fragment of the report,Terragni moves further and poses the question of the "art for the masses", intended as art serving the spiritual and esthetic aspirations of an entire nation.

In the case of the Danteum, because of its location in front of the ruins and the difficult subject of Dante's poem to be represented, Terragni is aware of the danger of producing a building that could be deemed as "rhetoric". So he resolves to design the exterior using a moderate and clean language,without unbalanced arches, columns or other redundant elements (only the huge sculptured reliefs by Sironi along the entrance wall); whilst on the interior he places all the architectural tools and plays able to move the poetic sensitivity of the visitor.Some years earlier he used these words to explain one of his works: "Whether the observer did or did not understand the allegoric concept of the monument is for me not a matter of de finitive importance. What matters is the esthetic relation established with the visitor, the fact to be 'moved' by it"[9].

The Danteum project, finally, raises the issue of what typology of building could bind together and satisfy all of these design aspects, such as the representation of the literary artwork, the connection with history and with the present, the esthetic values of the building.

The answer given by Terragni was to provide the foundation of a new architectural type.

The Danteum, as recognised by academics,constitutes an unprecedented typology of building,not a mere reproduction of the past typologies;instead, it consists of research, innovation,confrontation with the past and adherence to the present conditions, translated into architecture.

And here again, the idea of a "rational"architecture to be based on the foundation of new architectural types had already been brought up in the beginning of Group 7's theory and works.Indeed, this same approach may be found in another un-built project, contemporary of Danteum: the residential neighbourhood of Rebbio near Como,designed by Terragni and Alberto Sartoris in 1938(Fig. 15, 16). Even if defined by different scale,conditions and programme targets, this urban project takes start by the invention of mixed and various residential types. The innovative types were originated both from geographical and social conditions, and from the elaboration of residential buildings already built in Europe.

7 Conclusions

Terragni's design approach moves then towards the search of new architectural types, and this fact contributes to the uniqueness of his projects.Still after nearly 100 years their singularity keep animating a restless debate by critics and academics.

Notwithstanding the many different interpretations of Terragni's design intentions,his unique design method should be contemplated within his professional and theoretical path, and following its development together with the theory and works of the Italian Rationalist movement.

The Danteum project certainly is a milestone in the constellation of modern architecture masterpieces. The still lasting interest about it comes from its being un-built and surely unrepeatable,given its specific location and its challenging subject of representation of Dante's artwork. One could dare to say that these two works, theDivine Comedyand the Danteum, so distant in time and yet so intertwined, are both fundamental for the understanding of the multi-layered Italian culture in its speci fic time and context, respectively.

The occasion of celebrating 700 years from Dante's death could give impulse to the literary and architectural research to deepen the studies of such a fascinating theme and the connections between different forms of art.