Severe COVID-19 after liver transplantation, surviving the pitfalls of learning on-the-go: Three case reports

2021-01-14FelipeAlconchelPedroCascalesCamposJosePonsMarMartnezJosefaValienteCamposUrszulaGajownikMarOrtizLauraMartnezAlarcPascualParrillaRicardoRoblesFrancisconchezBuenoSantiagoMorenoPabloRamrez

Felipe Alconchel, Pedro A Cascales-Campos, Jose A Pons, María Martínez, Josefa Valiente-Campos, Urszula Gajownik, María L Ortiz, Laura Martínez-Alarcón, Pascual Parrilla, Ricardo Robles, Francisco Sánchez-Bueno, Santiago Moreno, Pablo Ramírez

Felipe Alconchel, Pedro A Cascales-Campos, Josefa Valiente-Campos, Laura Martínez-Alarcón, Pascual Parrilla, Ricardo Robles, Francisco Sánchez-Bueno, Pablo Ramírez, Department of Surgery and Organ Transplantation, Virgen de la Arrixaca University Hospital, Murcia 30120, Spain

Felipe Alconchel, Pedro A Cascales-Campos, Jose A Pons, María Martínez, Josefa Valiente-Campos, Urszula Gajownik, María L Ortiz, Laura Martínez-Alarcón, Pascual Parrilla, Ricardo Robles, Francisco Sánchez-Bueno, Pablo Ramírez, Department of Digestive, Endocrine and Abdominal Surgery and Transplantation, Biomedical Research Institute of Murcia (IMIBVirgen de la Arrixaca), Murcia 30120, Spain

Jose A Pons, Urszula Gajownik, María L Ortiz, Department of Hepatology, Virgen de la Arrixaca University Hospital, Murcia 30120, Spain

María Martínez, Department of Intensive Care Unit, Virgen de la Arrixaca University Hospital, Murcia 30120, Spain

Santiago Moreno, Department of Infectious Diseases, Ramon y Cajal Hospital, Madrid 28034, Spain

Abstract

Key Words: Liver transplantation; COVID-19; SARS-CoV-2; Cross infection; Nosocomial infection; Case report

INTRODUCTION

After the first cases of coronavirus-2 pneumonia (SARS-CoV-2) were detected in early December 2019 in Wuhan (Hubei, China)[1,2]a pandemic has overtaken hundreds of countries[3].The main active sources are currently located in Europe and the United States[4].This medical emergency has tested global healthcare systems, which have established strategic changes and protocols to prioritize healthcare and avoid overloading.The frequency of liver transplantation operations has been seriously affected.Transplant programs depend on the availability of donors, the vast majority of whom are deceased, and medical personnel normally oversee these programs in intensive care units, but these facilities are currently overcrowded.The result of these conditions has been a dramatic decrease in activity in all transplant groups around the world.In Spain, the world leader in organ donation, surgeons had access to the livers of about 100 deceased donors per week during the 3-month period before the detection of the first case of novel coronavirus (COVID-19); this number has since dropped dramatically to a level of only 15 donors per week[5,6].

In an effort to contain the pandemic, drastic community measures of social confinement and distancing have been established, and these measures extend to the healthcare environment, enhancing telematic activities for the ambulatory management of patients.At the in-hospital level, most of the preventive measures are aimed at preventing the spread of infection by healthcare professionals during the care of COVID-19 patients.The impact of nosocomial infection by COVID-19 has warranted little attention and could be especially relevant to transplant recipients during their hospitalization.

The main objective of our work is to communicate our experience in the therapeutic management of severe SARS-CoV-2 infection in three liver transplant patients who required invasive mechanical ventilation, two of whom had an infection of nosocomial origin.We also analysed some lessons learned from this experience.

CASE PRESENTATION

Since the detection of the first case of COVID-19 in our region on March 8, 2020, and until May 31st, 2020, a total of twelve liver transplant patients have been hospitalized in our liver transplant unit.

Chief complaints

Case 1:Sixty-one-year-old woman with a liver transplant in September 2019 for cryptogenic cirrhosis.In early March, she was admitted for diarrhea, and a few days later she developed acute respiratory failure, and heart failure.A first RT-PCR of SARS-CoV-2 from throat and pharyngeal swabs was negative but became positive three days later after a second RT-PCR was conducted due to high clinical suspicion (Figure 1).Treatment with hydroxychloroquine and lopinavir/ritonavir was then initiated, adjusting the tacrolimus levels, but the patient suffered progressive clinical and analytical worsening, with the need for invasive mechanical ventilation, associated with pulmonary superinfection byEnterococcus faecalisandEnterococcus faeciumdetected in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.Finally, the patient developed shock with multisystem failure and died in the third week of hospitalization.

Case 2:Sixty-eight-year-old male, transplanted on March 4, 2020, by non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.During the immediate post-transplant period, he was diagnosed with a biliary stricture and was treated endoscopically.His wife, the primary caregiver, tested positive for SARS-CoV-2viaRT-PCR from pharyngeal swabs on March 18, 2020, after reporting slightly compatible symptoms.All staff in contact with her, including the patient himself (who was initially negative), were evaluated with RT-PCR.Of a total of 40 people tested, one hepatologist was positive for SARS-CoV-2; this physician was in contact with all patients admitted at that time.Four days later, the patient, without symptoms, was discharged.Two days after discharge, the patient was readmitted for fever and cough, and the RT-PCR of SARS-CoV-2 was positive (Figure 1).Early treatment with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin was initiated, adjusting the doses of mycophenolic acid and tacrolimus.Seven days after the positive result, the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit due to deterioration of respiratory function requiring invasive mechanical ventilation and treatment with tocilizumab.The patient progressed satisfactorily to home discharge and asymptomatic, but still with a positive RT-PCR of SARS-CoV-2 two months later.

Case 3:Sixty-two-year-old woman who received a liver transplant in February 2019 secondary to primary biliary cholangitis and was discharged in the first week of March 2020 after an episode of constitutional syndrome.On April 6, 2020, she was readmitted with fever, dyspnea, and diarrhea, with a RT-PCR positive for SARS-CoV-2.Fortyeight hours later, the patient progressively deteriorated, requiring admission to intensive care unit with invasive mechanical ventilation, and was treated with tocilizumab in addition to hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, and methylpred- nisolone.Mycophenolic acid was suspended, and doses of tacrolimus were reduced to the minimum necessary.After four days of invasive mechanical ventilation, extubation was performed.In spite of the measures adopted, the patient evolved severely.Two months after the onset of the outbreak, and still with a positive RT-PCR of SARS-CoV-2, she developed a tracheoesophageal fistula.An esophageal prosthesis and an extracorporeal venovenous membrane oxygenation (vv-ECMO) were placed.Fortyfive days after the first positive RT-PCR of SARS-CoV-2 the virus was negative in the RT-PCR of the bronchoalveolar lavage.Unfortunately, the patient died eighty days after the onset of the outbreak in our liver transplant unit.

History of present illness

A cluster of three patients who temporarily coincided in the hospitalization ward developed a SARS-CoV-2 [reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) throat swab] infection.Given the use of anonymous clinical data and the observational approach of our paper, our work was exempt from approval from an ethics' board.Table 1 shows the main clinical features of these three patients.It is important to note that the wife of case 2, one hepatologist on the transplant team, and three nurses in the ward were also infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

In our transplant unit, the outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 began on March 18.After a positive RT-PCR result in case 1, the wife of case 2 also tested positive after reporting a fever and neck pain.Without delay, we conducted an exhaustive investigation on all the members of the unit (25 nurses and assistants, two cleaning staff, one warden, and nine physicians), with one nursing assistant testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 (hospital admission for ten days for pneumonia, without the need for intensive care unit), two nurses testing positive (one with a mild symptoms and negative RT-PCR at one month, and the other asymptomatic and negative at 13 d), and a hepatologist testing positive (negative at 15 d, asymptomatic and no admission).

Table 1 Details of the three cases reported

1Expressed as the median and range, of the analytical values since the RT-PCR of SARS-CoV-2 was positive until present.ALP: Alkaline phosphatase; BAL: Bronchoalveolar lavage; GGT: Gamma-glutamyltransferase; HCQ: Hydroxychloroquine; ICU: Intensive care unit; IMV: Invasive mechanical ventilation; LPV/r: Lopinavir/ritonavir; NASH: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; NE: Norepinephrine; RT-PCR: Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; vv-ECMO: Venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Physical examination

The remaining healthcare personnel who tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 were placed in preventive home confinement for 14 d, with negative RT-PCR determinations of SARS-CoV-2 thereafter.In addition, the hospital ward was closed for complete disinfection.

Further diagnostic work-up

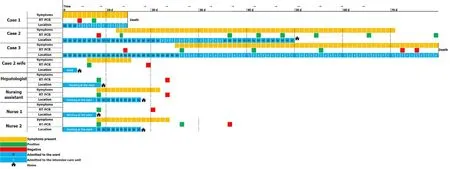

Figure 2 shows the epidemiological timeline of the three positive liver transplant recipients as well as the four contacts in the ward (one doctor, one assistant, and two nurses) who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The final diagnosis of the presented cases is severe COVID-19 after liver transplantation.

TREATMENT

Case 1 was treated with Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ, 200 mg daily), azithromycin (250 mg daily), lopinavir/ritonavir (one dose 400/100 mg) and vancomycin (1 g daily).The patient in case 2, underwent a treatment that included HCQ (200 mg daily), azithromycin (250 mg daily), tocilizumab (one dose 8 mg/kg) and methylprednisolone (180 mg three doses).In the case of patient 3, however, the outcome was more severe and required the use of a vv-ECMO in addition to HCQ (200 mg daily), azithromycin (250 mg daily), tocilizumab (one dose 8 mg/kg) and methylprednisolone (60 mg daily) (Table 1 and Figure 1).

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

All three patients required intensive care unit admission and invasive mechanical ventilation (Figure 1).Two of them (cases 1 and 3) progressed severely until death.The other one (case 2), who received tocilizumab, had a good recovery.In the outbreak, the wife of one of the patients and four healthcare professionals involved in their care were also infected (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

Figure 1 Clinical evolution of each case in a chronological perspective.

The most appropriate management for transplant recipients who develop COVID-19 and the impact of the infection on this population are not well known.In a previous publication on a population of 111 liver transplant patients with more than ten years of evolution and residents in lombardy (the epicentre of the pandemic in Italy), three deaths were reported due to COVID-19[7].The three liver transplant patients were all male and over 65 years old, with a body mass index greater than 28 kg/m2and with cardiovascular risk factors.The occurrence of co-morbidities such as older age,obesity,diabetes mellitus, use of anti-hypertensive drugs, and other cardiovascular risk factors have been associated with more severe clinical manifestations in the general population[8].There is no consensus regarding the optimal management of immunosuppressive treatment, and most groups suggest not to modify the immunosuppression strategies in asymptomatic or mild infections, but the experience reported in the literature in severe and critical conditions is variable, and some authors with whom we agree defend the decrease of immunosuppression[9].

In the physiopathology of SARS-CoV-2, the liver appears to be a susceptible organ[10]and liver damage occurs according to three mechanisms: (1) Direct cytotoxicity of the virus itself; (2) Indirect damage from autoimmune aetiology; and (3) Hepatotoxicity of drugs used in the management of the infection (remdesivir, tocilizumab, chloroquine and its derivatives, and azithromycin, among others)[11].Typical clinical manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection include fever, cough, and respiratory distress.The presence of gastrointestinal symptoms at the onset of the picture has been previously reported[12-15]and, along with the fever, were the initial manifestations in cases 1 and 3 of our series.In this initial phase, the RT-PCR determinations of SARS-CoV-2 were negative in both cases, and the patients presented gastrointestinal and non-respiratory symptoms.This pattern of symptoms was similar to that reported in a renal transplant patient with COVID-19[16,17].

The clinical situation worsened rapidly in case 1, evolving rapidly towards a fatal outcome.In this patient, elevated levels of C-reactive protein and procalcitonin were detected, as well as severe lymphopenia[18].In addition, the presence ofEnterococcus faeciumandEnterococcus faecaliswas found in the culture of the bronchoalveolar flush, which, in the context of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia (Figure 1A), undoubtedly triggered the clinical course toward shock and the death of the patient.Although some authors support the hypothesis that SARS-CoV-2 may cause true sepsis of viral origin by direct attack of the virus[19], this theory is not proven in practice, and we believe that that this theory does not explain by itself the fulminant evolution of this patient.Nevertheless, the clinical evolution was favourable in case 2, in which the patient was treated with hydroxychloroquine and tocilizumab.In case 1, we opted for the use of a lopinavir/ritonavir combination, although we do not know if this was correct, but the dose of tacrolimus was closely monitored due to the interaction of these drugs through the inhibition of cytochrome P450 family 3 subfamily A[20,21].Several studies have shown that patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 can develop a hyperinflammatory state which leads to an acute respiratory distress syndrome [acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)[22]].During ARDS pathogenesis, a "cytokine storm" including IL-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and IL-12 is released[23].These data suggest, that a blockage of pro-inflammatory pathways could be a therapeutic alternative in the management of patients with severe COVID-19.Tocilizumab is a monoclonal antibody that specifically binds to the IL-6 receptor and inhibits signal transduction mediated by the binding of this receptor to its ligand.In two of our patients, tocilizumab was administered early, even before the need for invasive mechanical ventilation, achieving favorable outcomes.In contrast, in case 1, where tocilizumab was not administered, a situation of shock and multiorgan failure was triggered, resulting in the death of the patient.These findings would be in consonance with what was previously published regarding ARDS and suggest that tocilizumab could be an effective treatment for severe patients with COVID-19.

The liver transplant population has several specific peculiarities.It has been described that, after infection, more than 50% of patients with a liver transplant develop severe forms of the disease[8].In addition, the time for virus detection tests among these patients to become negative (clearance) is longer than that among the general population, and positive RT-PCRs of SARS-CoV-2 have been described in transplant patients beyond 53 d from the first positive test[24], which carries a potentially higher risk of contagion and the need for a longer period of isolation[25].

The vast majority of measures to prevent infection in the population are focused on non-hospital settings (such as confinement and telemedicine).In hospitals, these measures are preferably designed to prevent the transmission of COVID-19 from patients to healthcare personnel, where the use of personal protective equipment is mandatory.Furthermore, in the case of patients with liver disease, additional measures must be taken.Xiaoet al[26]suggest, for example, that the communication between patients and medical staff should be done online and each patient taken care of by one attending doctor and one nurse exclusively.

Figure 2 Epidemiological evolution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 outbreak in our transplant division, according to the presence or absence of symptoms, the positivity of the reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, and the patients’ locations each day from symptoms onset.

Preventive measures should begin as soon as the recipient is admitted, including the existence of a specific safety circuit until the result of the RT-PCR is known.For example, two of our patients who were candidates for transplant in the last week have tested positive on the day of the transplant but had no symptoms, and the donor grafts were therefore transplanted to other recipients.In addition to community transmission (case 1), nosocomial transmission of the virus must also be considered (cases 2 and 3).Once a case of nosocomial transmission is discovered, special measures should be applied not only to ward staff but also to all ward patients and facilities.In our experience after case 2, the entire ward was evacuated, and a procedure of disinfection and a quarantine of the premises and of all healthcare staff who had worked on the ward were undertaken.

Another problem in relation to the in-hospital management of SARS-CoV-2–infected transplant patients resides in the discordance between the positivity of RT-PCR and the symptoms suggestive of COVID-19, indicating a high-risk window of infection[27].As other published works have examined[28],in the outbreak that took place in our unit, there was a period in which healthcare professionals and companions who were asymptomatic carriers of SARS-CoV-2 concurred in space and time with other patients and healthcare professionals who did not have the virus.These circumstances favored the propagation of the virus until the first positive case was detected and the necessary measures were taken.

A final, equally important aspect is the real impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on organ donation, transplant policies, and waiting list mortality, which altogether constitute the so-called “indirect mortality” from SARS-CoV-2.Most countries have implemented emergency policies to prevent contagion, ranging from issuing systematic screening tests for SARS-CoV-2 in all donors and recipients, limiting donation to far from the hospital where the graft will be implanted, restricting liver transplant activity only in acute liver failure or critical patients[29,30], and implementing telemedicine in outpatient follow-up.In these circumstances, increases in both mortality among those on the waiting list and in the number of drop-outs due to clinical worsening or tumour progression (indirect deaths from COVID-19) are to be expected.In fact, in Spain, organ donation and transplantation have decreased dramatically.Before the declaration of the state of alarm on March 13, 2020, there were 7.2 donors and 16 transplants per day on average, but since that date, the rates have fallen to an average of 1.2 donors and 2.1 transplants per day[5].

CONCLUSION

Therefore, there are several lessons learned from our experience.Firstly, early administration of anti-IL-6 monoclonal antibodies could be beneficial in slowing down the cytokine storm in critically ill patients with COVID-19.Secondly, the disease prodrome in two patients were the gastrointestinal and not the respiratory symptoms.Finally, COVID-19 is highly contagious, so drastic preventive measures and exhaustive epidemiological investigations must be conducted in the case of clinical suspected disease in the ward, even if the RT-PCR of SARS-CoV-2 has been tested negative.

Many uncertainties persist in relation to the diagnosis, treatment, and management of COVID-19 in liver transplant patients.It is certain that we will learn more about the disease and be able to treat it more effectively in the coming months.In the meantime, we are walking blind, and we must rely on our scarce previous experience, on our intuition, and on the oldest methodology in medicine: Trial and error.

杂志排行

World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Neoadjuvant treatment strategies for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

- Metabolic syndrome and liver disease in the era of bariatric surgery: What you need to know!

- Combined liver-kidney transplantation for rare diseases

- Hepatocellular carcinoma Liver Imaging Reporting and Data Systems treatment response assessment: Lessons learned and future directions

- Tumor necrosis family receptor superfamily member 9/tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 1 pathway on hepatitis C viral persistence and natural history

- Apatinib as an alternative therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma