Neoadjuvant treatment strategies for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

2021-01-14CliffordAkatehAslamEjazTimothyMichaelPawlikJordanCloyd

Clifford Akateh, Aslam M Ejaz, Timothy Michael Pawlik, Jordan M Cloyd

Clifford Akateh, Timothy Michael Pawlik, Department of Surgery, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH 43210, United States

Aslam M Ejaz, Jordan M Cloyd, Department of Surgery, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, United States

Abstract Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) is the second most common primary liver malignancy and is increasing in incidence.Long-term outcomes are optimized when patients undergo margin-negative resection followed by adjuvant chemotherapy.Unfortunately, a significant proportion of patients present with locally advanced, unresectable disease.Furthermore, recurrence rates are high even among patients who undergo surgical resection.The delivery of systemic and/or liver-directed therapies prior to surgery may increase the proportion of patients who are eligible for surgery and reduce recurrence rates by prioritizing early systemic therapy for this aggressive cancer.Nevertheless, the available evidence for neoadjuvant therapy in ICC is currently limited yet recent advances in liver directed therapies, chemotherapy regimens, and targeted therapies have generated increasing interest its role.In this article, we review the rationale for, current evidence for, and ongoing research efforts in the use of neoadjuvant therapy for ICC.

Key Words: Biliary tract cancer; Preoperative therapy; Conversion therapy; Down-staging; Hepatectomy; Liver resection

INTRODUCTION

Cholangiocarcinomas (CCA) are a heterogeneous type of biliary tract cancer (BTC) arising from the epithelial cells of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary tracts[1].CCAs are classified as distal bile duct, perihilar, or intrahepatic based on their anatomic location[2].Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) arises distal to the secondary biliary radicals and comprise approximately 20% of all CCAs.ICCs have distinct molecular, anatomic, clinical, and prognostic characteristics compared with other BTCs.Although relatively rare, the incidence of ICC has been increasing over the past decade and ICC is currently the second most common type of primary liver cancer.The optimal management of ICC includes surgical resection; unfortunately, a majority of patients will present with metastatic or locally advanced disease and are therefore not candidates for surgery.Even those patients with localized disease who undergo margin-negative resection are at high risk for recurrence, highlighting the need for effective systemic therapies.While the optimal systemic therapy given following resection (i.e., adjuvant therapy) continues to evolve, there is growing interest in the use of neoadjuvant therapy (NT) for ICC.Such strategies may effectively downstage patients with locally advanced disease in order to achieve surgical resection while prioritizing the early and guaranteed delivery of systemic therapy in order to improve long-term oncologic outcomes for this aggressive cancer.Recent advances in the molecular understanding of ICC, as well as the development of effective systemic and liver-directed therapies, have also increased interest in the use of NT.In this study, we review the rationale for, evidence of, and ongoing research efforts in the use of NT for ICC.

MANAGEMENT OF ICC

Surgical resection

Surgical resection remains the only treatment option with curative intent in the management of ICC[3,4].Unfortunately, only about 20%-30% of patients present with resectable disease.Given that most patients present with advanced disease, patient selection is critical to ensure that patients will benefit from surgery.All patients require comprehensive evaluation along three domains: Anatomic, biologic, and physical condition.Patients must have appropriate performance status to undergo major liver surgery without prohibitive medical comorbidities.Complete staging with cross-sectional imaging and tumor markers should be performed to ensure the absence of metastatic disease.In general, distant, contralateral hepatic, peritoneal, and lymph node metastases beyond the porta hepatis are contraindications to resection[5].As such, some guidelines recommend a diagnostic laparoscopy prior to resection[5,6].Dedicated, liver-protocol, contrast-enhanced imaging is needed to assess resectability.In general, a technically safe hepatic resection requires a future liver remnant (FLR) defined as at least two contiguous liver segments with intact arterial and portal venous inflow, intact hepatic vein outflow and intact biliary drainage.In general, an FLR of at least 20% is necessary for patients with normal liver function.For patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy or those with significant steatosis, an FLR of at least 30% is required.And for patients with underlying liver cirrhosis, an FLR of at least 40% is required[7].FLR is traditionally calculated by volumetric analysis using CT, MRI, or Scintigraphy.Several strategies can be employed to improve the FLR, including ligation of the feeding portal vessels or embolization[8,9].

Like most solid organ tumors, obtaining a margin negative (R0) resection is an important oncologic goal and one of the few metrics potentially under control of the surgeon.In a small series of 50 patients with locally advanced tumors by Langet al[10], the median survival after R0 resection was 46 movs5 mo for R1 resection[10].In a larger series of 224 patients, Yehet al[11]reported a median survival of 26.1 mo and 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year OS of 78.5%, 43.3%, and 28.6%, respectively in patients who underwent R0 resectionvsa median survival of 11.4, and 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year OS of 47.5%, 6.8%, and 4.5% for patients who had an R1 resection.The results are even worse for R2 resection in which the median survival was 5.8 mo and 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year OS was 24.0 %, 6.0%, and 0%, respectively[11].These results have been confirmed in larger studies and meta-analyses[12,13].While an R0 resection margin should clearly be the goal of surgery, the optimal margin width remains controversial with some data suggesting a wider margin (≥ 10 mm) is associated with improved outcomes[14-18].Portal lymphadenectomy is also recommended as part of the surgical approach to ICC.Lymphadenectomy is essential for accurate staging, determining prognosis, and guiding the use of adjuvant therapies[19,20].Removal of at least six lymph nodes is recommended by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network[21], although this is commonly not achieved[20].Limited data support the use of minimally invasive approaches at experienced centers and the use of vascular resection, when indicated, in order to achieve negative margins.

Adjuvant therapy

Even among patients who undergo a complete macro- and microscopic margin negative resection, patients can still experience a high incidence of recurrence.Indeed, ICC is an aggressive malignancy, and overall survival remains poor[22].For this reason, there has been a longstanding interest in the development of effective adjuvant therapies to reduce cancer recurrence.Fortunately, several recent prospective trials have provided new data on this controversial issue.The French PRODIGE 12–ACCORD 18 Trial was a phase III randomized trial that randomized patients to adjuvant chemotherapy (Gemcitabine/Oxaliplatin, GEMOX)vsobservation following R0 or R1 resection of BTCs (43% ICC).The investigators reported no difference in overall survival or relapse-free survival[23].The BILCAP trial randomized patients with resected ICC to capecitabine or observation following an R0/R1 resection.In this trial, 19% of the patients had ICC, 38% of whom had R1 resection, and 47% had nodal metastases.Patients who received adjuvant capecitabine experienced improved median overall survival (51.1 movs36.4 mo)[24].The ACTICCA-1 trial[25]and JCOG1202[26]are currently ongoing.Adjuvant radiotherapy and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) have also been investigated, but the data are still lacking[27-31].Based on these data, current guidelines recommend the use of adjuvant capecitabine following resection of any BTC, including ICC.

Metastatic disease

Unfortunately, most patients with ICC present with metastatic disease as many will not develop symptoms until an advanced stage.As surgical resection is not appropriate in the setting of metastatic disease, treatment goals focus on improving local control, treating symptoms, and extending survival.To that end, various systematic chemotherapy regimens and liver-directed therapies have been tried with varying success[32].The ABC-02 trial was a prospective randomized trial of 410 patients with locally advanced or metastatic BTCs (intrahepatic or extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, gallbladder cancer, or ampullary carcinoma) who were randomized to cisplatin plus gemcitabine (Gem-Cis) or gemcitabine alone.Patients treated with Gem-Cis had significantly better overall survival and progression-free survival, establishing this doublet regimen as the standard chemotherapy for advanced BTC[33].Recent trials have explored triplet gemcitabine-cisplatin-nabpaclitaxel, although further data are needed[34].Several mutations in IL-6, ErbB2, K-ras, BRAF, and COX-2, p53, P16, cyclin D1, and DNA repair enzymes have all been linked to ICC and provide a basis for targeted therapies.Most of the morbidity and mortality among patients with metastatic ICC is due to liver disease and liver failure.Therefore, the selective use of liver-directed therapies, even in the presence of metastatic disease, may improve local disease control, health related quality of life, and potentially overall survival[35].

RATIONALE FOR NEOADJUVANT THERAPY

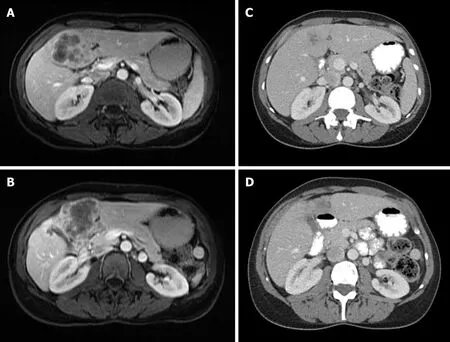

While the use of NT has been increasing in other common cancers, its use in ICC remains relatively rare[36-39].Thus, a sound rationale for the use of NT in BTCs is necessary as empirical data accrue (Table 1).As previously detailed, only a minority of patients presenting with ICC are eligible for resection; fewer patients successfully undergo an R0 resection.Yet the ability to achieve margin-negative resection is a primary determinant of long term survival outcomes[11,12,40,41].Therefore, a major impetus for pursuing NT is the potential to downstage locally advanced cancers and convert to resectable disease (Figure 1).Thus, NT given for this purpose is commonly referred to as downstaging or conversion therapy[42].

A second major motivation for the use of NT is to ensure its early and nearuniversal use.While current guidelines recommend the use of adjuvant therapy for essentially all patients with resected ICC, a significant proportion of patients are unable to initiate and/or complete adjuvant therapy due to postoperative complications or poor performance status following major liver surgery.For example, in a retrospective series of 72 patients who underwent resection for ICC, only 35% of the patients received chemotherapy[43].

Not only does the delivery of systemic therapies prior to surgery ensure receipt is not prevented by postoperative complications, it also prioritizes the use of systemic therapies for an aggressive cancer with a strong tendency for systemic recurrence.For example, a recent multi-institutional review of patients with resected ICC reported that approximately 22% of patients experienced very early recurrence (defined as within six months of surgery), which ultimately led to poor survival outcomes[43].It is likely that micrometastatic disease was present in these patients at the time of surgery and early systemic therapy may have been beneficial.Similarly, the use of NT also facilitates the appropriate selection of patients for a major surgery by ensuring that the rapid progression of metastatic disease does not occur while on systemic therapy.Recent prediction models may be useful in determining which patients with ICC may be best suited for NT[44,45].Finally, given the genomic, phenotypic, and clinical heterogeneity of patients with ICC, monitoring the response to NT radiographically, biochemically, and histopathologically provides important prognostic and therapeutic information.Thisin vivotest will only become more important with the development of more effective targeted therapies in the era of personalized medicine.

EVIDENCE FOR NEOADJUVANT THERAPY IN ICC

Systemic chemotherapy

There have been no prospective randomized trials evaluating the benefit of neoadjuvant chemotherapy among patients with BTC, including ICC.However, there are some case reports, single-institution studies, and some retrospective data to suggest its benefit (Table 2).Chemotherapy regimens often use a combination of Gem-Cis, based on data extracted from the ABC-02 trial[33].In some early studies of patients with locally advanced and unresectable tumors receiving Gem-Cis, 36.4% (8/22) in one study[46]and 25.6% (10/39) in another study[47]were able to be appropriately downsized and undergo resection.In a large single-center study of 186 patients with locally advanced ICC, 39/74 (53%) of patients who received NT were able to undergo resection[48].In a large meta-analysis of 18 studies and 1,880 patients, including eight studies with chemotherapy.Patients who underwent resection following downstaging had significantly longer median survival compared with patients who did not (29 movs12 mo,P< 0.001)[49].In another systematic review of 132 patients, 27 patients (20.5%) were downstaged to surgical resection candidates[42].In sum, these data support the use of systemic therapy among patients with locally advanced ICC as an attempt to downstage tumors to become resectable since achieving resection following conversion therapy is associated with improved long-term survival.

While the use of NT in locally advanced disease is indicated, the routine use of systemic therapy prior to surgery for patients with resectable disease is not well established.Yadavet al[50]evaluated the National Cancer Database and performed a propensity-matched comparison of patients who received NT prior to surgical resection to individuals receiving surgery and adjuvant therapy.Acknowledging the limitations in this type of retrospective review, patients who received NT before surgery experienced improved OS (median OS: 40.3 movs32.8 mo;P= 0.01)[51].However, in a multi-institutional study of 62 patients who received NT (44% chemotherapy, 29% transarterial therapy) prior to curative-intent resection for ICC, a comparison of propensity-score matched patients who underwent upfront surgery did not find any significant difference in survival[51].Clearly, more data are needed, preferably through well-designed prospective clinical trials, in order to define the indications for NT among patients with resectable ICC.

Table 1 Rationale for the use of neoadjuvant therapy in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

Table 2 Select studies on neoadjuvant systemic chemotherapy for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

TACE

While TACE is routinely used for patients with HCC[52]and neuroendocrine liver metastases[53], its appropriate use in ICC remains undefined.ICC is a hypovascular tumor and thus less responsive to TACE[54,55].However, since most of the morbidity and mortality associated with ICC results from overwhelming liver disease and liver failure, locoregional therapies such as TACE can be useful in controlling locally advanced disease.As such, in patients with ICC, TACE is traditionally used for those that are not eligible for surgery, as a palliative option, though it has been explored with downstaging intent (Table 3)[56,57].One of the early successes in the use of TACE as a conversion therapy was reported by Burgeret al[58]Seventeen patients with unresectable ICC under conventional TACE using cisplatin, doxorubicin, and mitomycin-C.Six of the patients had previously faced systemic therapy.TACE resulted in 75% tumor necrosis in 8 patients and tumor downstaging in 3 patients.Two of these patients were able to undergo surgical resection[58].Herberet al[59]investigated the role of TACE using mitomycin C in 15 patients with unresectable disease and noted stable disease in 9 patients, partial response in 1, and tumor progression in 4 patients; no conversions to resection were reported[59].Gusaniet al[60]compared patients who received combination systemic gemcitabine and TACE to gemcitabine alone, and reported significant improvement in survival among patients who received TACE (13.8 movs6.3 mo, respectively;P= 0.0005)[60].A large retrospective review of 198 patients with advanced ICC undergoing transarterial therapies reported a complete or partial response in 25.5% of patients and stable disease in another 61.5%, suggesting a role for the use of TACE as neoadjuvant treatment (of note, 23.2% of the patients received yttrium-90 radioembolization)[61].In another large series by Voglet al[62], there was no difference in survival between different TACE regimens[62].

Table 3 Select studies on neoadjuvant transarterial chemoembolization for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

Drug-eluting bead chemoembolization (DEB-TACE) allows for the delivery of highly concentrated doses of chemotherapy in addition to conventional chemoembolization.The beads limit the systemic availability and systemic toxicities of chemotherapy.In a retrospective study from Italy, 127 patients with advanced ICC underwent DEB-TACE or polyethylene glycol drug-eluting microspheres (PEGTACE).Of the 109 patients treated with DEB-TACE, 7% had a partial response, 88% had stable disease, and 5% had progressive disease.Four patients (3.8%) in the DEBTACE group were downsized and successfully underwent resection[63,64].Multiple studies have evaluated DEB-TACE for unresectable ICC[65-67]; in general, few conversions to resectability have been reported.

Taken together, these findings suggest a potential role for TACE in the neoadjuvant treatment of patients with locally advanced ICC.However, while radiographic responses are observed, the majority of patients demonstrated stable disease, and conversions to resectable disease are the exception.Future studies may consider combination regimens that aim to enhance the response rate while treating/preventing the risk of systemic disease.

Transarterial radioembolization/selective internal radiation therapy

Transarterial radioembolization with yttrium-90 (Y-90) is an alternative transarterial therapy that is used in the management of locally advanced ICC and may downstage patients to resectability (Table 4).In an early open-label trial of Y-90 for ICC, 24 patients with advanced and unresectable ICC were treated with Y-90.Of the 22 patients with follow-up imaging, 6 patients demonstrated a partial response, 15 had stable disease, and 1 patient had progressive disease; 1 (4%) patient was downstaged and underwent resection[68].In 2013, Mouliet al[69]reported on a series of 60 patients with ICC treated with Y-90 transarterial radioembolization (TARE).By EASL criteria, 33 patients had partial or complete response disease, and 12 patients showed stable disease.In this cohort, 5 patients successfully underwent an R0 resection[69].In 2015, Al-Adraet al[70]performed a pooled analysis of several studies reporting on the use of Y-90 for patients with unresectable ICC.In this pooled data of 73 patients, the partial response rate following Y-90 treatment was 28%, and 54% had stable disease at 3 mo; 7 (10%) patients underwent surgical resection post TARE[70].

Rayaret al[71]combined Y-90 with systemic therapy as an option to downstage unresectable ICC.Of the 45 patients treated with the combination regimen, ten were downstaged to potentially resectable, and 8 (17.8%) patients underwent resection[71].Other studies have reported similarly low conversion rates with neoadjuvant Y-90 treatment[72-74].In a large retrospective single-institution study of 169 patients, Ribyet al[75]compared patients who underwent upfront resection to those who received downstaging chemotherapy with or without selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT) prior to surgical resection.Interestingly, patients with unresectable disease at presentation who became resectable after downstaging had similar median overall survival as patients with resectable disease who underwent upfront surgery (32.3 NTvs45.9 primary surgery,P= 0.54).In addition, patients who received SIRT as part of their downstaging NT were more likely to undergo an R0 resection[75].This approach has recently been validatedviathe MISPHEC trial, which was a prospective, multi institutional trial of 41 previously untreated patients with locally advanced ICC.The patients received concomitant cisplatin and gemcitabine chemotherapy, followed by TARE with Y-90 microspheres.The response rate was 39%by RECIST criteria and 93%by Choi criteria.9 patients (22%) were downstaged to resectable candidates, and 8 (20%) of them subsequently underwent an R0 resection.Additionally, subgroup analysis showed that 30% of patients in the trial with disease involving only 1 hemiliver disease could be downstaged[76].

Table 4 Select studies on neoadjuvant transarterial radioembolization/selective internal radiation therapy for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

Figure 1 Locally advanced intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

In summary, these findings suggest that while TARE provides good locoregional control, however the low response rates, when used alone, limits its application as a downstaging treatment for neoadjuvant intent.Recent studies combining TARE with systemic therapy hold promise and should be the subject of future trials.

Hepatic artery infusion

Given the toxicities associated with systemic chemotherapy, hepatic artery infusion(HAI) pumps were initially developed for the management of colorectal liver metastases but, more recently, trialed in patients with ICC (Table 5).One of the earliest experiences with HAI therapy in the management of ICC was performed by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in a phase II trial.Twenty-six patients with unresectable ICC were treated with HAI FUDR therapy.Fourteen patients (53.8%) experienced a partial response, 11 (42.3%) had stable disease, and 1 patient (3.8%) had disease progression[77].In a follow-up study, the authors added systemic bevacizumab to HAI therapy which resulted in worsened toxicity without improved outcomes[78].In 2015, Konstantinidiset al[79]reported on large series of 167 patients with advanced/unresectable, 104 of whom had disease confined to the liver, and 63 had regional nodal disease.Patients had either received HAI or HAI plus systemic therapy.Although there was no significant difference in tumor response by RECIST criteria, patients who received HAI plus systemic chemotherapy had better overall survival (30.8 mo) compared with patients who received systemic therapy alone (18.4 mo)[79].Eight patients from the cohort (4 from each group) underwent resection with curative intent.Despite the low rate of conversion, the results remain promising.In another smaller series reported by Massaniet al[80], 11 patients with unresectable disease underwent HAI therapy with fluorouracil and oxaliplatin, 5 patients had a partial response of whom 3 underwent resection.2 of these patients had more than 70% tumor necrosis on pathology[80].

In summary, HAI therapy may induce higher response rates for ICC, especially when combined with systemic chemotherapy.However, conversion rates remain low, and, unlike other transarterial therapies, HAI therapy requires surgical placement of an implanted pump, which carries morbidity and delays the use of systemic therapy.In addition, data supporting its use are largely retrospective and have not been studied among patients undergoing true neoadjuvant intent.Future multi-institutional trials are needed to validate this approach and compare it to other approaches.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Targeted therapies

The prognosis of patients with locally advanced, recurrent and/or metastatic ICC remains poor even with contemporary systemic therapy.As such, there is great interest in the development of novel targeted therapies[81].Next-generation sequencing of patients with advanced and refractory tumors have led to an improved understanding of the genetic changes driving cholangiocarcinogenesis.For example, mutations in KRAS have been identified and are an independent predictor of worse survival after hepatectomy[82].Mutations in BRAF[83], EGFR[84], PI3K[85], and TP53[86]have also been reported with varying percentages.In addition, there are novel antitumor therapies directed at the fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 fusion protein (FGFR)[87,88], isocitrate dehydrogenase-1 (IDH1), and IDH2[89], BAP1[90], BRAF V600[91], and Her2/neu mutations[82].Immunotherapies, including anti-PDL1 and anti-CTLA-4 inhibitors have been trialed inBTCs as well including ICC.About 10% of ICC lack mismatch repair mechanisms and as such are good targets in immunotherapy[92,93].In the Phase II KEYNOTE-158 Study, 41% of patients with cholangiocarcinoma had an objective response[94].While most of these targeted therapies are currently being investigated in patients with advanced disease and early phase trials, these therapies hold great potential for use in the neoadjuvant and perioperative setting.

Table 5 Select studies on neoadjuvant hepatic artery infusion for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

Liver transplantation

While liver transplantation (LT) is indicated in the treatment of HCC meeting Milan criteria[95], the role of LT in the management of ICC remains controversial and, in general, remains limited to specialized centers and for patients on clinical trials.A challenge in interpreting the current literature is that most of the early studies combined hilar cholangiocarcinoma and ICC, making the results difficult to interpret.But even in those studies, transplant outcomes for ICC were generally very poor[96,97].Interestingly, the standardization of transplantation protocols that include strict inclusion criteria and NT regimens has led to increased transplant rates for hilar cholangiocarcinoma[98-100].Indeed, NT regimens for hilar cholangiocarcinoma are incorporated into the preoperative protocol at most LT centers[101,102].It is therefore assumed that the development of effective programs for LT for ICC will similarly require effective neoadjuvant therapies.

One of the earliest successful experiences was reported by Gosset al[103]In their review of 127 patients who underwent LT for primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), ten patients (8%) had incidental CCA on explant pathology.More importantly, they had equivalent survival to those without ICC (100%, 83%, and 83% at 1, 2, and 5 years, respectively)[103]A recent large multicenter trial by Sapisochinet al[104]found that patients with tumors less than 2cm did not have any added risk of recurrence.13 patients (8 TACE, 3 RFA and 2 PEI) received some neoadjuvant therapy.Preoperative treatment had no association with outcomes[104].A more recent larger experience with pre-transplant regimens for ICC was reported by Lunsfordet al[105]Patients with nonmetastatic locally advanced ICC were treated with a gemcitabine-based chemotherapy regimen.After six months of radiographic response or stability, patients were listed for transplantation.The median duration to transplantation was 26 mo.Overall survival was 100% (95%CI: 100-100) at 1 year, 83.3% (27.3-97.5) at 3 years, and 83.3% (27.3-97.5) at 5 years.Three patients developed recurrent disease at a median of 7.6 mo (IQR 5.8-8.6) after transplantation, with 50% (95%CI: 11.1-80.4) recurrence-free survival at 1, 3, and 5 years[105].Rayaret al[71]reported on another case of an unresectable lesion that was downstaged with multimodal therapy, including Y-90 TARE, systemic chemotherapy, and external beam radiation.The patient was transplanted after several months of disease stability.Although several barriers exist, these recent studies highlight the potential for improved outcomes for patients with advanced ICC using LT.Future research will require the design of effective multidisciplinary programs for patients that incorporate NT protocols, not only to bridge patients while on the waitlist, but also to ensure appropriate oncologic selection for transplantation.

Biomarkers

The design and validation of effective NT protocols also require the identification of appropriate biomarkers to guide its use and gauge response to therapy.The discovery of somatic mutations in ICC has led to renewed interest in the use of these as potential prognostic and predictive biomarkers[106,107].For example, KRAS mutations, one of the most frequently seen mutations in ICC, is also associated with worse survival after resection in some studies[83,108].MUC-44 has been linked to poor outcomes in mass forming ICC subtype[109].The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte (N:L) ratio has equally been associated with worse survival in ICC[110].CEA and CA-19 have very wide-ranging sensitivities and specificities in ICC[111].Recent studies have highlighted the ability of machine learning to identify which patients with ICC may be best suited for NT[44,45].Despite these recent advances, research on biomarkers for ICC is still lacking, and future trials are needed.

Ongoing trials

While interest in neoadjuvant approaches in other gastrointestinal cancers continues to drive new clinical trials, prospective trials of NT for ICC remain limited.An ongoing trial (NCT03579771) evaluating the benefit of neoadjuvant gemcitabine, cisplatin, and nab-paclitaxel is currently accruing.Another trial (NCT03867370) aims to investigate the benefit of neoadjuvant Toripalimab (a PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitor) in patients with resectable HCC and ICC, although this study has not started accrual yet.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, a sound rationale for the use of NT exists in ICC, particularly among patients with locally advanced disease.Given the importance of a margin-negative resection on overall prognosis, NT with a downstaging intent should be given in these patients.While numerous systemic and transarterial therapies have been reported in limited series, strong evidence for the superiority of one approach over another is lacking.Recent evidence has offered support for the use of combination strategies (e.g., systemic therapy with TARE) in order to augment the response and increase the proportion of patients downstaged to resectability.Future comparative effectiveness studies are needed to evaluate the optimal neoadjuvant approach, and ongoing research into targeted therapies for ICC may offer new opportunities for personalized neoadjuvant treatment.Finally, while margin-positive resection rates and disease recurrence is common even among patients with resectable disease, the evidence of NT in this patient population is extremely limited.Thus, the role of routine NT in patients with resectable ICC should be limited to patients with high-risk disease and preferably as part of a clinical trial.In the meantime, oncologic surgery that includes a margin-negative resection with formal lymphadenectomy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy remains the recommended approach.

杂志排行

World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Metabolic syndrome and liver disease in the era of bariatric surgery: What you need to know!

- Combined liver-kidney transplantation for rare diseases

- Hepatocellular carcinoma Liver Imaging Reporting and Data Systems treatment response assessment: Lessons learned and future directions

- Tumor necrosis family receptor superfamily member 9/tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 1 pathway on hepatitis C viral persistence and natural history

- Apatinib as an alternative therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma

- Hepatitis B virus detected in paper currencies in a densely populated city of India: A plausible source of horizontal transmission?