PNPLA3 and TM6SF2 polymorphisms in Brazilian patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

2021-01-14QuelsonCoelhoLisboaMateusJorgeNardelliPatrciadeArajoPereiraboraMarquesMirandaStephanieNunesRibeiroRaissaSoaresNevesCostaCamilaAzevedoVersianiPaulaVieiraTeixeiraVidigalTeresaCristinadeAbreuFerrariClaudiaAlvesCouto

Quelson Coelho Lisboa, Mateus Jorge Nardelli, Patrícia de Araújo Pereira, Débora Marques Miranda, Stephanie Nunes Ribeiro, Raissa Soares Neves Costa, Camila Azevedo Versiani, Paula Vieira Teixeira Vidigal, Teresa Cristina de Abreu Ferrari, Claudia Alves Couto

Quelson Coelho Lisboa, Mateus Jorge Nardelli, Patrícia de Araújo Pereira, Débora Marques Miranda, Stephanie Nunes Ribeiro, Raissa Soares Neves Costa, Camila Azevedo Versiani, Paula Vieira Teixeira Vidigal, Teresa Cristina de Abreu Ferrari, Claudia Alves Couto, Departament de Clínica Médica, Faculty of Medicine, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte 30130100, Brazil

Abstract

Key Words: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; Genetic variation; Single nucleotide polymorphism; Genotype; Brazil; Fibrosis

INTRODUCTION

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is characterized by hepatocellular accumulation of triglycerides (TG) in the absence of excess alcohol consumption or any other cause of secondary liver steatosis[1,2].Currently, it is the most common chronic liver disease in Western countries, with an estimated prevalence of 25% globally and 32% in South America[3,4].NAFLD is strongly associated with the metabolic syndrome [obesity, insulin resistance/type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and dyslipidemia][4,5]and encompasses a spectrum of liver diseases ranging from simple steatosis (SS), which is usually benign, to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which may lead to liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma[6,7].In fact, liver fibrosis is an independent risk factor of NAFLD severity and liver-related mortality[8,9].

Although highly prevalent, only a minority of NAFLD patients develop significant fibrosis and associated morbidity[10,11].Thus, NAFLD is considered a complex disorder in which the disease phenotype results from an interaction between environmental exposure and susceptible polygenic background that comprises multiple independent modifiers[12,13].

In recent years, genome-wide association (GWA) and candidate gene studies have greatly contributed to understanding the genetics of NAFLD and their influence on prognosis[14-16].In 2008, Romeoet al[17]identified that the mutation I148M encoded by the G allele at rs738409 in the gene patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 (PNPLA3) is a major determinant of inter-individual and ethnicity-related differences in hepatic fat content.These findings have been confirmed in different populations through GWA[18-20]and candidate gene[21-26]studies, which demonstrated thatPNPLA3polymorphism was associated with greater susceptibility to NAFLD development and more severe histological and clinical forms.

In 2014, Kozlitinaet al[27]identified that the E167K (rs58542926 C/T) variant in theTM6SF2gene was also associated with increased liver fat content.This polymorphism was later associated with greater susceptibility to NAFLD and advanced histological NASH[28,29].In this context, there is only one genetic study in Brazilian NAFLD patients[30], andTM6SF2polymorphism has not yet been analyzed in this population.

Therefore, in this study, we investigated the association betweenPNPLA3andTM6SF2genotypes and clinical parameters of NAFLD, and analyzed the genotype variations as markers of liver histological features in Brazilian adult NAFLD patients.We also investigated the distribution of these genotype variations among Brazilians.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and study design

A cross-sectional study was performed at the Outpatient NAFLD Clinic, Medical School of Federal University of Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil.A total of 285 individuals (208 females and 77 males) were enrolled; of which, 148 patients had features of NAFLD (case patients) and 137 were non-NAFLD control subjects.

The case patients were confirmed to have hepatic steatosis by liver ultrasonography (US) according to established criteria[31]; additionally, other causes of liver disease were excluded, including elevated alcohol intake (men, > 30 g/d; women, > 20 g/d), autoimmune disorders (autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cholangitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis), hereditary hemochromatosis, alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, Wilson disease and hepatitis B or C virus infection.Patients who had decompensated cirrhosis or were taking drugs that induce steatosis were excluded.The NAFLD patients underwent liver biopsy according to the clinical protocol suggested by Chalasaniet al[2].Increased risk of NASH and/or advanced fibrosis included the presence of metabolic syndrome or significant fibrosis predicted by noninvasive methods.Subjects who had a liver biopsy showing steatosis, hepatocyte ballooning and lobular inflammation[1]were classified into the NASH group (n= 54) and individuals without an indication for liver biopsy and those who did not fulfill the NASH criteria on biopsy were classified into the SS group (n= 94).

Control subjects were selected from patients attending our institution at the Outpatient Intestinal Disease Clinic whose gender matched the NAFLD patients (97 females and 40 males).Individuals in the control group underwent a standard health examination, liver US and liver biochemistry.They were selected if there was no evidence of fatty liver on US and no liver biochemical abnormalities.Furthermore, the control subjects did not present any of the features of the metabolic syndrome as defined by the International Diabetes Federation criteria[32]and did not abuse alcohol.

Subjects from whom deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) could be obtained for genotypingPNPLA3at rs738409 andTM6SF2at rs58542926 were included in the analyses.The case participants and the controls were selected from patients attending our institution from January 2017 to December 2018.

All the investigations performed in this study were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments.Written informed consent was obtained from each subject, and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (CAAE 23610614.0.0000.5149).

Liver biopsy and histopathological evaluation

Liver biopsy was performed in patients with NAFLD who were at increased risk of having NASH and/or advanced fibrosis (i.e.,presence of metabolic syndrome or advanced fibrosis indicated by the NAFLD Fibrosis Score[33])[2].Liver biopsy specimens were routinely fixed in 40 g/L formaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin, Masson trichrome and silver impregnation for reticular fibers analysis.The same liver pathologist, who was blinded to the patients’ information,analyzed all the exams.All the biopsies were at least 2 cm in length and contained a minimum of 8 portal tracts.The histological criterion for the diagnosis of NAFLD was macrovesicular fatty deposit in more than 5% of the hepatocytes.The NASH diagnostic criterion was the simultaneous presence of steatosis, ballooning and lobular inflammation in the liver biopsy, according to the Fatty Liver Inhibition of Progression algorithm[1].Steatosis was graded based on the percentage of hepatocytes containing large and medium-sized intracytoplasmic lipid droplets, on a scale of 0 to 3 (S0: < 5%; S1: 5%-33%, S2: 34%-66%, S3: > 67%).Lobular inflammation was defined as a focus of 2 or more inflammatory cells within the lobule organized either as microgranulomas or located within the sinusoids.Foci were counted at × 20 magnification (grade 0: none; 1: ≤ 2 foci per lobule; 2: > 2 foci per lobule).Hepatocyte ballooning was graded from 0 to 2 (0: Normal hepatocytes with cuboidal shape, sharp angles and pink eosinophilic cytoplasm; 1: Presence of clusters of hepatocytes with a rounded shape and pale cytoplasm; 2: As for grade 1, associated with at least one enlarged ballooned hepatocyte).Severity of fibrosis was scored according to the Pathology Committee of the NASH Clinical Research Network method[34]and was expressed on a 4-point scale, as follows: 0, none; 1, perivenular and/or perisinusoidal fibrosis in zone 3; 2, combined pericellular and portal fibrosis; 3, septal/bridging fibrosis; 4, cirrhosis.The grade of NASH activity (A) was calculated by the addition of the grades of ballooning and lobular inflammation (from A0 to A4).Based on the Steatosis, Activity, and Fibrosis score evaluation[35], NASH was also classified histologically into mild (A ≤ 2 and F ≤ 2) and significant (A > 2 and/or F > 2).

Clinical and laboratory evaluation

Patient weight and height were measured using a calibrated scale after removing shoes and heavy clothing, if any.Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the ratio of weight (in kilograms)/height (in square meters).Waist circumference was measured at the mid-level between the lower rib and the iliac crest[36].Venous blood samples were obtained from the subjects after an overnight fast (12 h) to measure plasma glucose, serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), gamma glutamyltranspeptidase, total cholesterol,high-density lipoprotein cholesterol,low-density lipoprotein cholesterol(LDL), TG, total bilirubin, platelets, and ferritin concentrations.Serum vitamin D and fasting insulin levels were obtained only from the NAFLD patients.Homeostasis Model Assessment was used to evaluate insulin resistance and was calculated as fasting serum insulin (μU/mL) × fasting plasma glucose (mmol/L)/22.5[37].All biochemical parameters were measured in a conventional automated analyzer.A blood sample was also obtained for DNA extraction and genotyping.

DNA preparation and single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted using the high salt method[38].A predesigned TaqMan®probe (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States) was purchased for genotyping rs738409 (C_7241_10) and rs58542926 (C_89463510_20).Genotyping was performed by real-time PCR in allelic discrimination mode, using the Strategene®Mx3005 equipment (MxPro QPCR System, 2007 Software, La Jolla, CA, United States).PCR protocols were carried out according to the TaqMan®Genotyping Master Mix manufacturer’s instructions (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States).The success rates of these assays were > 99%.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 23.0 software (IBM, United States).Data are expressed as mean ± SD for normally distributed continuous variables, as median and interquartile range when the distribution was skewed, or as number and percentage for qualitative variables.Continuous variables distribution was assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk test.The Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was checked for all individual single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)[39].The Student’st-test or a non-parametric test,i.e., Mann-Whitney U-test were used to compare quantitative data, as appropriate.χ2test or Fisher’s exact tests were used for comparison of categorical data.All tests were two-tailed andPvalues < 0.05 were considered significant.Variables associated with aPvalue < 0.20 in univariate analysis were included in multivariate analysis.

Multinomial binary logistic regression analysis was performed to detect the effect of a SNP mutation on liver histology.For association analysis, thePNPLA3rs738409 and theTM6SF2rs58542926 variants were coded in an additive and dominant genetic model.The model fit was assessed by the Hosmer-Lemeshow test.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Clinical features, anthropometric variables and laboratory findings of the 148 NAFLD patients and 137 controls are shown in Table 1.

Comparing the NAFLD group with the controls, there were no significant differences regarding gender and age distributions.NAFLD patients showed a significantly higher frequency of the metabolic syndrome components–T2DM, arterial hypertension and dyslipidemia–and significantly higher values of BMI.Fasting glucose, TG, AST, ALT, ALP and gamma glutamyltranspeptidase serum concentrations were also significantly higher in the NAFLD subjects (Table 1).

Liver biopsy was performed in 65 of the NAFLD patients (43.9%).Based on histological findings, 54 (36.5%) individuals (7 with cirrhosis) were included in the NASH group.The SS group included 94 (63.5%) NAFLD subjects without a clinical indication for histological examination (i.e.patients without metabolic syndrome and/or advanced fibrosis by noninvasive methods) and those without NASH on biopsy.Clinical and demographic characteristics of the NASH and SS patients are depicted in Table 2.

A significantly higher proportion of subjects in the NASH group had T2DM or impaired fasting glucose (IFG) when compared to the SS group, but there was no difference regarding the frequency of arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia or BMI.AST, ALT and ferritin serum concentration levels were significantly higher in the NASH group than in the SS group (Table 2).Fibrosis was detected in 35 of the 65 biopsies: F1 = 18, F2 = 5, F3 = 5, and F4 = 7.

Association between clinical and metabolic characteristics and the PNPLA3 variant

ThePNPLA3gene was successfully amplified by real-time PCR in all NAFLD patients and controls.The minor allele frequency (MAF) ofPNPLA3rs738409 in overall patients was 34%, and the genotype frequencies were CC 47%, CG 38% and GG 15%.The Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was demonstrated for the selected SNP ofPNPLA3in the NAFLD (P= 0.26) and the control (P= 0.07) groups.

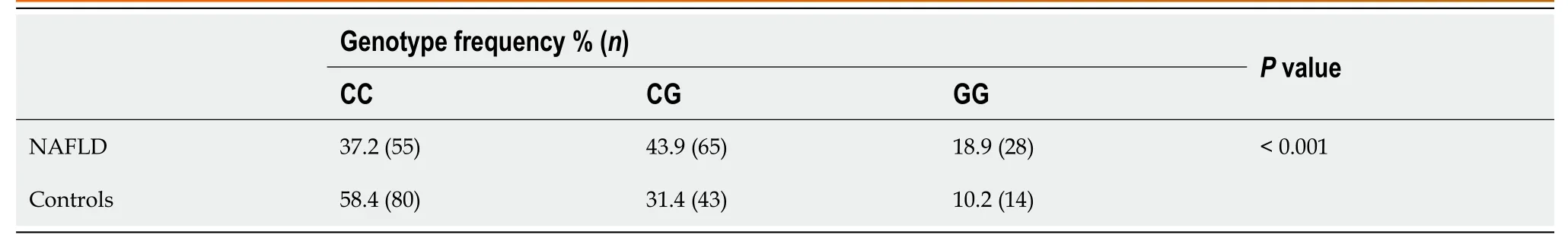

The C and G allele frequencies in the NAFLD patients were 59% and 41%, respectively, and were 74% and 26% among the controls.PNPLA3genotypes are described in Table 3; their frequencies were significantly different between the NAFLD patients and the controls (P< 0.001).

The chance of NAFLD was increased by the presence of the G allele [odds ratio (OR) = 2.37, 95%CI: 1.47-3.82;P< 0.001], even after adjustment for age, gender, BMI and T2DM/IFG (OR = 1.69, 95%CI: 1.21-2.36;P= 0.002) (Table 4).This association was even stronger when CC homozygotes were compared with GG homozygotes (OR = 3.13, 95%CI: 1.49-6.57;P= 0.003).

In the NAFLD group, no association was found between PNPLA3 CCvsCC + CG genotypes concerning BMI (P= 0.421), waist circumference (P= 0.641), FG (P= 0.795), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (P= 0.723), low-density lipoprotein (P= 0.614) and TG (P= 0.269).On the other hand, serum AST (P< 0.001) and ALT (P= 0.002) were associated with the presence of rs738409 G allele atPNPLA3.

Association between histological features and the PNPLA3 variant

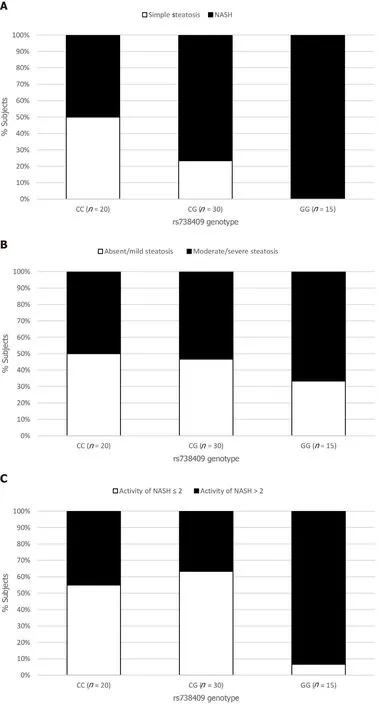

The NAFLD group was assessed for the association between histological features including steatosis, ballooning, inflammation and fibrosis, and thePNPLA3genotype.Although the presence of hepatic steatosis on US was associated with the G variant rs738409, we found no association between the histological grade of steatosis and the presence of the G allele (Figure 1B).The severity of both lobular inflammation and hepatocellular ballooning was associated with thePNPLA3variant G allele (P< 0.001).

The prevalence of NASH was 50% in the NAFLD subjects with the CC genotype (10/20), 77% in those with the CG genotype (23/30), and 100% in those with the GG genotype (15/15) (P< 0.001) (Figure 1A).G allele presence increased the chance of NASH (OR = 2.21, 95%CI: 1.04-4.71,P= 0.039), especially after adjusted for age, gender, BMI and T2DM (OR = 3.50, 95%CI: 1.84-6.64,P< 0.001).This chance was even higher when we analyzed homozygosis GGvsCC (OR = 6.07, 95%CI: 2.06-17.81,P= 0.001), even after the same adjusted model (OR = 5.53, 95%CI: 2.04-14.92,P= 0.001) (Table 4).

The chance of significant NASH activity (A > 2) was higher in homozygosis GG (OR = 17.11; 95%CI: 1.87-156.25;P= 0.012)in multivariate analysis.Based on the Steatosis, Activity, and Fibrosis score, significant NASH was associated withPNPLA3GG genotype (Figure 1D).

The presence of fibrosis was observed in 7 of the 20 (35%) patients who underwent liver biopsy with the CC genotype; in 16 of 30 (53%) with the CG genotype, and in 12 of 15 (80%) with the GG genotype (P= 0.01) (Figure 1F).Presence of the G allele increased the chance of liver fibrosis in a model adjusted for age, gender, BMI and T2DM/IFG (OR = 3.05; 95%CI: 1.01-9.17;P= 0.04).The GG homozygosis increased the chance of fibrosis (OR = 7.42; 95%CI: 1.55-35.47;P= 0.01) after the same adjusted model (Table 5).

Association between the TM6SF2 variant, clinical characteristics and histological features

TheTM6SF2rs58542926 genotypes were confirmed to be in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium with a MAF in the overall NAFLD cohort of 8%.The genotype frequencies were CC 84%; CT 15%; and TT 1%.

TM6SF2genotype distribution among NAFLD and controls are described in Table 6.There was no significant difference in the allele distribution between cases and controls (P= 0.78).The frequencies of T alleles were 9% in the controls and 8% in NAFLD patients.The presence of T alleles was not associated with NAFLD or NASH in univariate or multivariate analysis.TM6SF2T alleles were more frequent in the NASH group (22%) than in the SS group (12%), but without statistical significance (P= 0.89).

Finally, there was no association between the geneTM6SF2rs58542926 and liver steatosis (P= 0.62), ballooning (P= 0.14), lobular inflammation (P= 0.99) and fibrosis (P= 0.89).

Table 2 Clinical and demographic characteristics of the nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and simple steatosis population

Table 3 PNPLA3 rs738409 genotype frequencies in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients and controls

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that thePNPLA3genotype is associated with NAFLD susceptibility and different clinical forms.The presence of the G allele was associated with NAFLD occurrence when compared to the controls, and with NASH when compared to SS, in addition it was associated with higher NASH histological activity score and the presence of fibrosis in individuals with histopathological assessment.TheTM6SF2genotype frequency was analyzed for the first time in a Brazilian population, and we did not observe any significant difference in the variant gene distribution between NAFLD patients and controls, or between NASH and SS subjects.

Table 4 Association between the PNPLA3 rs738409 genotype and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, adjusted for age, gender, body mass index and diabetes

Table 5 Association of the PNPLA3 rs738409 genotype and activity of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and fibrosis, adjusted for age, gender, body mass index and diabetes, evaluated by multivariate binary logistic regression analysis

Table 6 TM6SF2 rs58542926 genotype frequencies in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients and controls

The first GWA study in NAFLD identified a single highly significant association between increased hepatic TG content and thePNPLA3[17].Subsequent studies demonstrated that this variant was also associated with the progression of NAFLD in different ethnic populations around the world[21,25,26,41,42].

In the Brazilian population, there are only two studies on NAFLD andPNPLA3genotypes[30,43].Machadoet al[43]investigated the gene polymorphism in T2DM individuals and Mazoet al[30]evaluated the genetic variation in NAFLD subjects compared to controls.TheTM6SF2polymorphisms were assessed in the investigation by Mazoet al[30]; however, they were not in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in the NAFLD group, which precluded this analysis.Therefore, the present study contributes to thePNPLA3genotype study in Brazil and is the first study to document the distribution ofTM6SF2alleles and genotypes in Brazilian NAFLD patients.

Figure 1 Relationship between the rs738409 genotype and the histological parameters.

In this sample, the frequency of the minor (G) allele atPNPLA3rs738409 was higher (34%) than the frequency reported in European (23%) and African (15%) individuals, lower than observed in American subjects (45%), and similar to that found in East Asian individuals (35%).The observed differences in the MAF for rs738409 between different racial groups are in agreement with the differences in the risk of hepatic steatosis[44].

Findings from this study confirmed the association betweenPNPLA3and liver fat content, and showed that the rs738409 G allele increases the chance of NAFLD in Brazilian patients by about 1.6-fold, regardless of metabolic syndrome features.Furthermore, GG homozygosis seems to have an even stronger association with liver fat.

NAFLD is currently considered the hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome[45].In a recent meta-analysis, most of the included studies showed lack of association betweenPNPLA3genotypes and BMI, fasting glucose levels and Homeostasis Model Assessment[21].In the study by Machadoet al[43], analysis of the associations betweenPNPLA3genotypes and the metabolic syndrome components in a T2DM population demonstrated that the G allele was only associated with better glycemic control.In the current study, we found no association between anthropometric and metabolic parameters with thePNPLA3gene variant, which confirms previous results.

The presence of the G allele was not only associated with NAFLD occurrence, but also with the NASH phenotype in patients who underwent liver biopsy.This finding was different to a previous Brazilian analysis[30], in which NASH occurrence was not associated with the presence of the G allele in NAFLD individuals.This could be attributed to the fact that the prior Brazilian study enrolled a small number of SS individuals (n= 34) and the SS: NASH proportion was 1.0: 6.3, whereas in our study it was 1.7: 1.0.

Interestingly, no significant association between rs738409 and steatosis grade was found in our study.However, the grade of NASH histological activity and the presence of fibrosis were associated with thePNPLA3genotype.In fact, our data support that more aggressive disease with higher fibrosis scores was associated with rs738409 variation–subjects with higher activity scores (A > 2) were 17 times more likely to be GG homozygous than to be homozygous for the C allele; and subjects with liver fibrosis were 7.4-fold more likely to be GG homozygous than to be CC.Lack of significant association between histological steatosis grade and rs738409 genotype was observed in at least two other case-control studies[46,47]; and an association betweenPNPLA3and inflammation activity and fibrosis in NAFLD has also been found in other studies[21,23,25].Our study, however, was limited by the fact that only 44% of the patients underwent liver biopsy.

As stated, theTM6SF2rs58542926 genotypes were described in this study for the first time in Brazilians.The MAF (8%) was similar to that observed in a Northern European sample (7%)[48], but lower than that observed in other European samples (12% and 13%)[28,29].Different to that described in other studies[27,29,41,42], we did not find significant differences regarding theTM6SF2genotypes between NAFLD patients and controls, or between NASH and SS individuals.This finding suggests that in the Brazilian population, the genetic variants of rs58542926TM6SF2may have a distinct influence on NAFLD than that observed in other populations, which is understandable, as Brazilian NAFLD patients have been reported as an admixed population presenting genetic ancestry contributions from European (48.8%), African (41.7%) and Amerindian (9.5%)[49].Besides that, asTM6SF2MAF is less frequent in the general population, larger samples may be required to confirm this finding.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we observed thatPNPLA3may be involved in the progression of NAFLD in the Brazilian population.Individuals who had histopathological assessment and more advanced liver disease were more likely to carry the G allele.TheTM6SF2genetic variants were not associated with NAFLD susceptibility and severity in the population studied, although further studies with larger samples are required to confirm these findings.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common chronic liver disease in Western countries and encompasses a spectrum ranging from simple steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).Although highly prevalent, only a minority of NAFLD patients develop significant fibrosis.Thus, NAFLD is considered a complex disorder in which the disease phenotype results from an interaction between environmental exposure and a susceptible polygenic background.Polymorphisms ofPNPLA3andTM6SF2genes have been associated with greater susceptibility to NAFLD development in previous studies.

Research motivation

There is only one genetic study in Brazilian NAFLD patients, andTM6SF2polymorphism has not yet been analyzed in this population.As Brazilian NAFLD subjects have been reported as an admixed population presenting diverse genetic ancestry contributions, it is relevant to study the associations between various genotypes and fatty liver disease progression.

Research objectives

We aimed to investigate the association betweenPNPLA3andTM6SF2genotypes and clinical parameters of NAFLD, and analyzed the genotype variations as markers of liver histological features in adult Brazilian NAFLD patients.We also investigated the distribution of these genotype variations among Brazilians.

Research methods

This cross-sectional study enrolled 285 individuals, of which 148 patients had features of NAFLD (case patients) and 137 were non-NAFLD control subjects.NAFLD was diagnosed based on hepatic steatosis by liver ultrasonography and exclusion of other causes of liver disease.Patients who had decompensated cirrhosis or were taking drugs that induce steatosis were excluded.From the total of NAFLD patients, 65 underwent liver biopsy according to the clinical protocol of increased risk for NASH and/or advanced fibrosis.DNA was obtained for genotypingPNPLA3at rs738409 andTM6SF2at rs58542926.

Research results

PNPLA3CC, CG and GG genotype frequencies were 37%, 44% and 19%, respectively, in NAFLD patients and were 58%, 31% and 10% in controls (P< 0.001).In a model adjusted for gender, age, body mass index and type 2 diabetes mellitus, the G allele increased the chance of NAFLD (OR = 1.69, 95%CI: 1.21-2.36,P= 0.002) and NASH (OR = 3.50, 95%CI: 1.84-6.64,P< 0.001).The chance of NASH was even higher with GG homozygosis (OR = 5.53, 95%CI: 2.04-14.92,P= 0.001).No association was found between G allele and the features of metabolic syndrome.In the histological assessment,PNPLA3genotype was not associated with steatosis grade, although GG homozygosis increased the chance of significant NASH activity (OR = 17.11, 95%CI: 1.87-156.25,P= 0.01) and fibrosis (OR = 7.42, 95%CI: 1.55-34.47,P= 0.01) in the same adjusted model.TM6SF2CC, CT and TT genotype frequencies were 83%, 15% and 0.7%, respectively, in NAFLD patients and were 84%, 16% and 0.7% in controls (P= 0.78).Presence of the T allele was not associated with NAFLD or NASH, or with histological features.

Research conclusions

PNPLA3may be involved in the susceptibility and progression of NAFLD and NASH in the Brazilian population.More advanced histological liver disease was associated with the G allele.TheTM6SF2genetic variants were not associated with NAFLD susceptibility and progressive histological forms in the population studied.

Research perspectives

The description of variant genotypes distribution in NAFLD Brazilian patients contributes to a better understanding of the disease clinical characteristics and atypical features in this population.As theTM6SF2polymorphism is less frequent in the general population, investigations with larger sample are needed.Further studies may investigate additional particular components of fatty liver disease in Brazil.The role of genotyping assessment for risk stratification is still uncertain.

杂志排行

World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Neoadjuvant treatment strategies for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

- Metabolic syndrome and liver disease in the era of bariatric surgery: What you need to know!

- Combined liver-kidney transplantation for rare diseases

- Hepatocellular carcinoma Liver Imaging Reporting and Data Systems treatment response assessment: Lessons learned and future directions

- Tumor necrosis family receptor superfamily member 9/tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 1 pathway on hepatitis C viral persistence and natural history

- Apatinib as an alternative therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma