澧县‘红地球’葡萄表面黑色组曲霉种群结构及产毒情况研究

2020-12-28页非黄晓庆王忠跃

页非 黄晓庆 王忠跃

摘要 葡萄和葡萄制品面临着真菌毒素的威胁,这些真菌毒素主要来自于黑色组曲霉Aspergillus section Nigri。本研究对采自湖南省澧县‘红地球葡萄上的黑色组曲霉进行了分离鉴定及种群结构分析,并采用超高效液相色谱串联质谱技术(ultra performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry,UPLC-MS/MS)對12株代表菌株产赭曲霉毒素(ochratoxin A, OTA)和伏马毒素B2(fumonisin B2, FB2)的能力进行了测定。结果表明,澧县地区‘红地球葡萄带菌率为92%。基于钙调素序列,分离得到的131株黑色组曲霉分属于5个种,其中A.aculeatinus为优势种。12株代表菌株均不产生OTA;A.welwitschiae(4/5)及A.niger(2/2)可产生FB2,平均产毒量分别为336 ng/g及741.37 ng/g。上述结果为评估国内葡萄表面黑色组曲霉及其毒素的污染风险提供参考。

关键词 葡萄; 黑色组曲霉; 赭曲霉毒素(OTA); 伏马毒素B2(FB2)

中图分类号: S 436.631.1

文献标识码: A

DOI: 10.16688/j.zwbh.2019422

Abstract Grapes and grape products are threatened by mycotoxins, caused by some species of Aspergillus section Nigri. In this study, based on calmodulin gene sequencing, using ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS), the Aspergillus section Nigri population and its toxigenicity in grapes in Lixian county of Hunan province were studied to confirm the food safety of table grapes. A total of 131 Aspergillus section Nigri strains were isolated from grape samples with the isolation frequency was 92%, and five species of Aspergillus section Nigri were identified, with A.aculeatinus as the dominant species. The mycotoxin tests of 12 isolated strains showed that none of them produced ochratoxin A. A.welwitschiae (4/5) and A.niger (2/2) could produce fumonisin B2, with an average toxin yield of 3.36 ng/g and 741.37 ng/g, respectively. This study provided a reference for evaluating the occurrence of Aspergillus section Nigri and its toxigenicity on the surface of grapes in China.

Key words grape; Aspergillus section Nigri; ochratoxin A; fumonisin B2

葡萄作为鲜食水果不仅肉多汁甜,还有着极高的营养价值,一直深受消费者喜爱。然而由于鲜食葡萄中可溶性固形物含量极高,并且果皮薄而嫩,导致其在生长期间以及采后运输、贮藏过程中极易破损从而遭受各类真菌的感染,进而产生不同的真菌毒素,并且这些真菌毒素也会随着后续加工进入各类葡萄制品中,给食品的质量安全带来了隐患,对人类的健康构成了威胁。研究发现,当温度高于37℃并且空气湿度较大时,葡萄极易遭受曲霉属Aspergillus真菌的污染[1]。黑色组曲霉Aspergillus section Nigri是曲霉属一个重要类群,至少包含27个种[2],其与葡萄酸腐病(grape sour rot)和曲霉黑腐病(Aspergillus black rot)联系紧密。酸腐病是危害许多葡萄品种的一种收获前病害,其症状包括浆果开裂和浆果组织被破坏等,是一种复杂的病害,其病原涉及多种丝状真菌和细菌[3]。相关研究表明,黑色组曲霉能够引起葡萄酸腐病[4]。在美国加利福尼亚州,炭黑曲霉A.carbonarius及黑曲霉A.niger是造成葡萄酸腐病的主要种[3]。曲霉属真菌引起的黑腐病也是发生在葡萄上的众多腐烂病害之一,主要由黑色组曲霉引起[5]。这种病以黑腐病的形式出现在浆果上,表现为大量的真菌孢子侵入浆果使其完全变成空壳且干燥。病原菌分布于浆果表皮,随采收进入贮藏空间,对浆果有潜在威胁[6-7]。除了产量损失外,曲霉属真菌中的部分种能产生真菌毒素,污染葡萄及其制品,造成食品安全上的重大隐患。研究表明,黑色组曲霉中炭黑曲霉等5个种可以产生赭曲霉毒素A(ochratoxin A,OTA)[8-9],黑曲霉与A.welwitschiae可以产生伏马毒素B2(fumonisin B2, FB2)[10-12],黑曲霉可产伏马毒素B4(FB4)[13]。

赭曲霉毒素是由赭曲霉A.ochraceus、炭黑曲霉及疣孢青霉Penicillium verruculosum等产毒菌所产生的一种有毒代谢产物[14],其中赭曲霉毒素A(OTA)分布最广,毒性最强。联合国世界卫生组织国际癌症研究机构在1993年将赭曲霉毒素A(OTA)列为人类2组B类致癌物,可造成人体肾脏、神经系统以及免疫系统损伤,进而诱发畸变、癌变等[15-18]。伏马毒素由 Gelderblom等[19]首次从串珠镰刀菌Fusarium moniliforme的培养液中分离出来,是一类由不同的多氢醇和丙三羧酸组成的结构类似的双酯化合物。在收割、储藏和加工等采后各个环节中极易污染粮食、水果和蔬菜等各种农副产品[20-21]。伏马毒素对人体和动物的损害极大,研究表明,伏马毒素与食管癌高发具有极高的关联性[22]。这两种毒素广泛存在于各种食物中,如谷物制品、咖啡、香料等,水果中主要以葡萄及其制品为主[23-26]。目前,葡萄及其制品真菌毒素污染的相关研究主要集中在国外,据报道葡萄在生长及储运的各个阶段均会受到黑色组曲霉的污染[27-29],且不同品种对产毒菌侵染和毒素积累的抗性水平有明显差异[30]。Qi等发现加拿大32%的鲜果葡萄中含有FB2,含量在1~15 ng/g[31]。葡萄酒中真菌毒素污染则更为普遍,欧洲各国葡萄酒中OTA检出率为17%~98%,南美洲为8%~40%,大洋洲澳大利亚为15%,北非摩洛哥高达100%[32]。Christopher等对产自美国11个葡萄产区的41份葡萄酒样品进行检测,发现OTA污染率高达74%[33]。国内关于真菌毒素在葡萄及其制品上的污染的研究较少,主要集中在葡萄酒的真菌毒素污染情况及检测方法[34-37]方面,少部分关于葡萄鲜果污染情况的相关研究[38]。随着国外关于葡萄及其制品被曲霉毒素污染的报道逐渐增多,葡萄上真菌毒素的污染问题也越来越被重视。

湖南澧县以盛产优质葡萄出名,但由于该地区地处于亚热带季风气候区,夏季高温多雨的气候适宜曲霉的生长,鲜果遭受曲霉污染的风险较大。本研究以澧县地区鲜食葡萄‘红地球为对象,采用表皮分离培养法对葡萄表面黑色组曲霉进行分类,基于钙调素序列鉴定分析其种群结构,利用超高效液相色谱串联质谱技术(UPLC-MS/MS)对其产毒情况进行检测,以期为鲜食葡萄的食品安全评价提供依据。

1 材料与方法

1.1 试验材料

样品采集于2018年9月上旬。在澧县地区选择3个葡萄园,品种为‘红地球,处于成熟期。每个葡萄园采集7~8个果穗,各果穗之间相隔10 m,在每个果穗上剪取2粒健康葡萄,共采集50粒。

葡萄糖及蔗糖购于北京化工厂;琼脂、酵母膏、磷酸氢二钾、七水硫酸亚铁、七水硫酸镁、硝酸钠、氯化钾、五水硫酸铜购于国药集团化学试剂有限公司;色谱甲醇、色谱乙腈,色谱甲酸购于Thermo Fisher Scientific;E-Z96真菌基因组DNA提取试剂盒(D3390-02)购于OMEGA;FB2、OTA标准品购于Pribolab。

1.2 试验方法

1.2.1 黑色组曲霉的分离

用灭菌的手术刀与手术镊从健康葡萄样品上3个不同的部位取下大约0.5 cm×0.5 cm大小的果皮,按照三点接种法且外果皮朝下放置在CYA培养基[2]上,一粒葡萄对应一皿,共50皿。将样品倒置于培养箱25℃黑暗处理3~5 d,待葡萄表皮周围长出菌落,统计带菌率。

1.2.2 黑色组曲霉菌种的分子鉴定

将葡萄果皮周围的菌落逐一转接于另一干净的CYA平板上进行纯培养,并对菌株进行编号。用接种针挑取新培养好的目标菌落的孢子囊于含有1 mL无菌水的离心管中,用移液枪吸打形成孢子悬浮液,吸取2 μL孢子悬浮液制成临时玻片在显微镜下观察,并逐步稀释,直至孢子悬浮液浓度约为1×105个/mL。取2 μL在 CYA培养基上划线,随后于霉菌培养箱25℃黑暗培养1~2 d。从划线部位选取单个菌落,用灭菌接种针挑至新的CYA平板中,重复3皿,倒置于霉菌培养箱25℃黑暗培养3~4 d。选取一皿切下长×宽约为1.5 cm×0.5 cm的菌条放入2 mL冻存管,加入30%甘油,放置在-80℃冰箱保存;另选取一皿刮下菌丝置于冻存管中用于DNA的提取。

利用E-Z96真菌基因组DNA提取试剂盒提取曲霉的基因组DNA,以提取的基因组DNA为模板,利用引物[2]CMD5(5′-CCGAGTACAAGGARGCCTTC-3′)和CMD6(5′-CCGATRGAGGTCATRACGTGG-3′)进行Calmodulin(CaM)基因保守序列的PCR扩增,片段大小约为600 bp。PCR反应体系为50 μL,0.4 mol/L上、下游引物各2 μL,Mix 25 μL,DNA模板2 μL,超純水19 μL。PCR扩增条件为:94℃预变性10 min;94℃变性15 s,55℃退火30 s,70℃延伸40 s,35个循环;最后72℃延伸7 min,4℃保存。PCR产物用1%琼脂糖电泳检测。PCR产物送至生工生物工程(上海)股份有限公司进行测序,利用Geneious软件BLAST功能将测序结果与黑色组曲霉Calmodulin基因参考序列[2]进行比对,得到菌种鉴定结果。

测序结果采用Geneious软件进行单倍型序列鉴定,将单倍型序列采用ClustalW方法进行多序列比对,然后采用RaxML 8.0软件GTRGAMMA模型构建最大似然树。根据系统发育树聚类结果,确定菌株所属种。

1.2.3 毒素检测

根据相关文献报道[8-12],从分离的菌株中选择可能产毒的菌种, 包括5株塔宾曲霉A.tubingensis、5株百岁兰曲霉A.welwitschiae、2株黑曲霉Aniger共12株。对这12株菌株进行活化。吸取1 μL保存的孢子悬浮液置于6 cm PDA培养基上,倒置培养3~4 d,用手术镊夹取少量菌丝置于1 mL去离子水中,振荡混匀,吸取2 μL滴于9 cm CYA培养基中央,黑暗倒置培养12 d。第13天使用规格3 mm的打孔器在菌落中心取10个琼脂栓放入5 mL离心管,称重并加入1.5 mL色谱纯甲醇[39],振荡3 min,黑暗静置1 h以上。将静置后的提取物10 000 r/min离心10 min,上清液先后经045 μm和0.22 μm微孔滤膜过滤。取1 mL过滤的溶液打入2 mL色谱瓶内,使用UPLC-MS/MS进行毒素检测。

FB2标准品浓度梯度设置为 5、25、50、100、250、500 ng/mL,OTA标准品浓度梯度设置为25、50、100、250、500 ng/mL。流动相由0.1%甲酸(A)和乙腈(B)组成。线性梯度洗脱程序如下:0 min 90% B,1.5 min 10% B(保持1 min),2.6 min 90% B, 保持5 min平衡。流速为0.3 mL/min,进样量2 μL。质谱测定参数见表1。通过全扫描/质谱多反应监测技术(multiple reaction monitoring, MRM)确定FB2及OTA的质子化离子峰,二级质谱分析得到各自碎片离子的信息,选取碎片离子峰值相对较高的 2 个碎片离子作为定量离子和定性离子。Intelistart 自动优化各质谱参数。

2 结果与分析

2.1 带菌率分析

本研究总共采集50份葡萄样品,其中46份样品分离到黑色组曲霉,带菌率为92%,共分离得到131株黑色组曲霉。

2.2 菌种鉴定及病原菌的种群结构分析

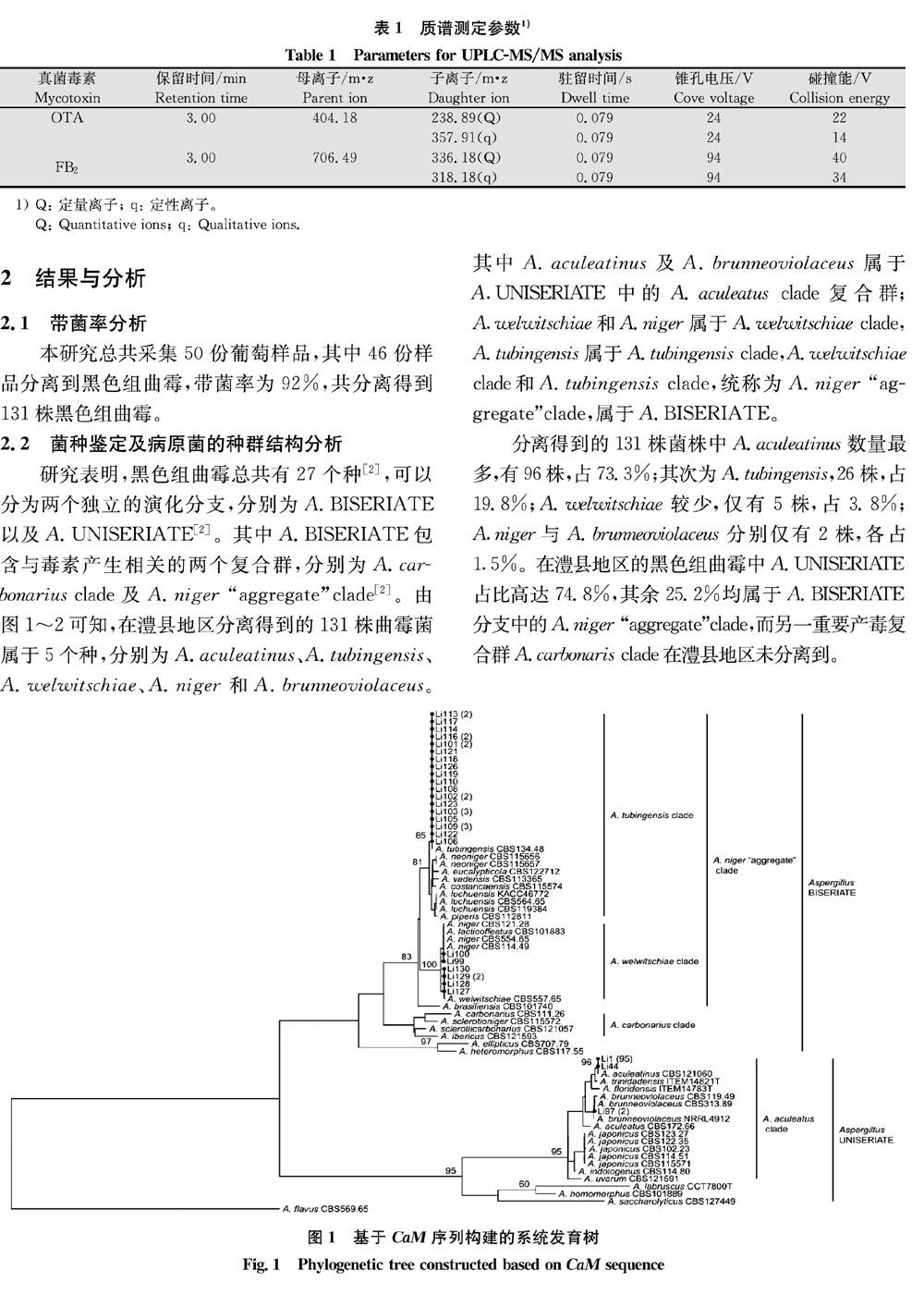

研究表明,黑色组曲霉总共有27个种[2],可以分为两个独立的演化分支,分别为A.BISERIATE以及A.UNISERIATE[2]。其中A.BISERIATE包含与毒素产生相关的两个复合群,分别为A.carbonarius clade及A.niger “aggregate”clade[2]。由图1~2可知,在澧县地区分离得到的131株曲霉菌属于5个种,分别为A.aculeatinus、A.tubingensis、A.welwitschiae、A.niger和A.brunneoviolaceus。其中A.aculeatinus及A.brunneoviolaceus属于AUNISERIATE中的A.aculeatus clade复合群;Awelwitschiae和A.niger属于A.welwitschiae clade,A.tubingensis属于A.tubingensis clade,A.welwitschiae clade和A.tubingensis clade,统称为A.niger “aggregate”clade,属于A.BISERIATE。

分离得到的131株菌株中A.aculeatinus数量最多,有96株,占73.3%;其次为A.tubingensis,26株,占19.8%;A.welwitschiae较少,仅有5株,占3.8%;Aniger与A.brunneoviolaceus分别仅有2株,各占15%。在澧县地区的黑色组曲霉中A.UNISERIATE占比高达74.8%,其余25.2%均属于A.BISERIATE分支中的A.niger “aggregate”clade,而另一重要产毒复合群A.carbonaris clade在澧县地区未分离到。

2.3 毒素检测结果

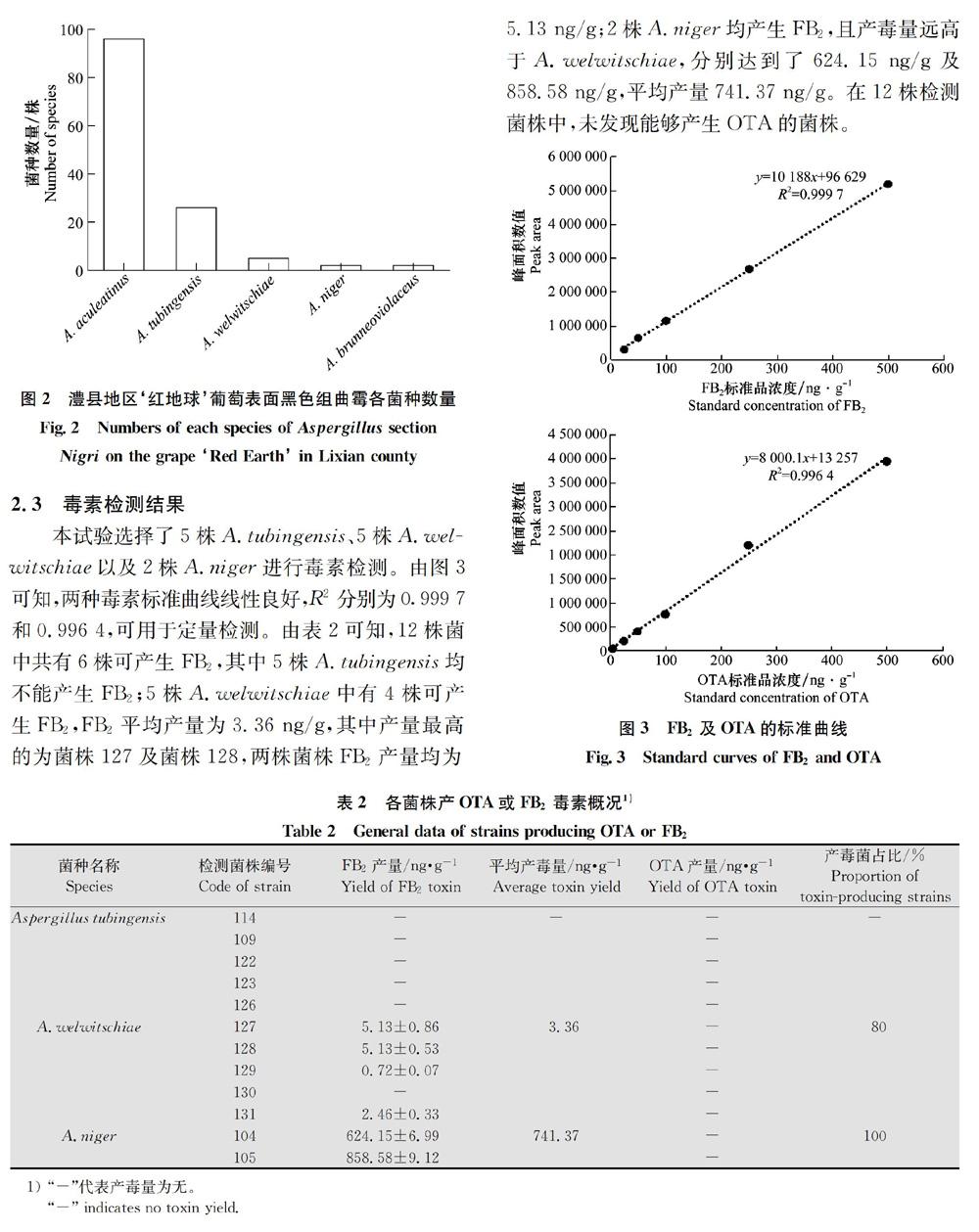

本试验选择了5株A.tubingensis、5株A.welwitschiae以及2株A.niger进行毒素检测。由图3可知,两种毒素标准曲线线性良好,R2分别为0999 7和0.996 4,可用于定量检测。由表2可知,12株菌中共有6株可产生FB2,其中5株A.tubingensis均不能产生FB2;5株A.welwitschiae中有4株可产生FB2,FB2平均产量为3.36 ng/g,其中产量最高的为菌株127及菌株128,两株菌株FB2产量均为5.13 ng/g;2株A.niger均产生FB2,且产毒量远高于A.welwitschiae,分别达到了624.15 ng/g及858.58 ng/g,平均产量741.37 ng/g。在12株检测菌株中,未发现能够产生OTA的菌株。

3 讨论

本研究发现,澧县地区的‘红地球葡萄黑色组曲霉带菌率较高,根据前期研究,推测是因为当地夏季高温高湿,十分适宜黑色组曲霉的生长[1]。本研究在湖南省澧县共鉴定到5种黑色组曲霉,优势种为A.aculeatinus,与其他国家相比,种群组成有明显差异。塞浦路斯[40]地区共分离得到5种黑色组曲霉,优势种为A.tubingensis;意大利[41]及加拿大[31]均鉴定得到6种黑色组曲霉,优势种分别为A.tubingensis及A.welwitschiae;在澧县地区AUNISERIATE分支占比最高;A.BISERIATE分支中A.niger “aggregate” clade次之,并未分离到A.carbonarius clade;在阿根廷[27]、意大利[41]及以色列[42]对葡萄表面黑色组曲霉种群组成研究中,A.niger “aggregate” clade占比最高,A.UNISERIATE次之,A.carbonarius clade最少,但也均高于7.0%;在西班牙[28]、法國[43]及澳大利亚[44]的相关研究中,A.niger “aggregate”clade占比最高,Acarbonarius clade次之,A.UNISERIATE最少。澧县地区的黑色组曲霉种群组成与上述报道葡萄种植区存在较大差异,这可能与地区间气候条件差异有关。毒素测定结果表明,被检测的A.tubingensis、A.welwitschiae及A.niger菌株均不产生OTA,大部分A.welwitschiae产生FB2[31]。与已有报道相同[29],A.niger全部可产生FB2,且产毒量较高。此前有报道认为A.tubingensis[45]可产生OTA,但最新研究表明其为不产OTA种群[46],本研究也证实了这一结论,所有检测的A.tubingensis均不产生OTA。有相关文献报导黑曲霉A.niger可产生OTA[47],但频率较低,比例分别为3.0%(8/257)[48]及16.7%(5/30)[49],也有文献报道未检测到产OTA的A.niger菌株[50]。本研究测定的Aniger菌株均不产生OTA,说明A.niger造成的OTA污染在这一区域风险较低。菌种A.niger是否产生OTA毒素以及其产毒特性还值得研究。综上,澧县地区的黑色组曲霉带菌率较高,有潜在的病害威胁。但产毒种频率较低,对澧县葡萄可能造成毒素污染风险的为A.niger以及A.welwitschiae产生的FB2。根据本研究结果,应进一步开展采后贮藏期间的葡萄样品检测,对黑色组曲霉进行持续监测,并且加大样本量对毒素污染风险继续进行更深入的评估。

参考文献

[1] VALERO A, MARN S, RAMOS A J, et al. Ochratoxin a-producing species in grapes and sun-dried grapes and their relation to ecophysiological factors [J]. Letters in Applied Microbiology, 2005, 41(5): 196-201.

[2] SAMSON R A, VISAGIE C M, HOUBRAKEN J J, et al. Phylogeny, identification and nomenclature of the genus Aspergillus [J]. Studies in Mycology, 2014, 78: 141-173.

[3] CRISTINA P, TRANG T N, WALTER D G. A novel fungal fruiting structure formed by Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus carbonarius in grape berries [J]. Fungal Biology, 2015, 119(9): 784-790.

[4] ROONEYLATHAM S, JANOUSEK C N, ESKALEN A, et al. First report of Aspergillus carbonarius causing sour rot of table grapes (Vitis vinifera) in California [J]. Plant Disease, 2008, 92(4): 651.

[5] SOMMA S, PERRONE G, LOGRIECO A F, et al. Diversity of black Aspergilli and mycotoxin risks in grape, wine and dried vine fruits [J]. Phytopathologia Mediterranea, 2012, 51(1): 131-147.

[6] COZZI G, PASCALE M, PERRONE G, et al. Effect of Lobesia botrana damages on black Aspergilli rot and ochratoxin A content in grapes [J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2006, 111(S1): S88-S92.

[7] VISCONTI A, PERRONE G, COZZI G, et al. Managing ochratoxin A risk in the grape-wine food chain [J]. Food Additives and Contaminants, 2008, 25(2): 193-202.

[8] BEJAOUI H, MATHIEU F, TAILLANDIER P, et al. Conidia of black Aspergilli as new biological adsorbents for ochratoxin A in grape juices and musts [J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2005, 53(21): 8224-8229.

[9] El-KHOURY A, RIZK T, LTEIF R, et al. Occurrence of ochratoxin A-and aflatoxin B1-producing fungi in Lebanese grapes and ochratoxin a content in musts and finished wines during 2004 [J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2006, 54(23): 8977-8982.

[10]MEDINA A, MATEO R, LPEZOCAA L, et al. Study of Spanish grape mycobiota and ochratoxin A production by isolates of Aspergillus tubingensis and other members of Aspergillus section Nigri [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2005, 71(8): 4696-4702.

[11]MOGENSEN J M, FRISVAD J C, THRANE U, et al. Production of fumonisin B2 and B4 by Aspergillus niger on grapes and raisins [J]. Agriculture Food Chemistry, 2010, 58(2): 954-958.

[12]FRISVAD J C, SMEDSGAARD J, SAMSON R A, et al. Fumonisin B2 production by Aspergillus niger [J]. Agriculture Food Chemistry, 2007, 55(23): 9729-9732.

[13]NOONIM P, MAHAKARNCHANAKUL W, NIELSEN K F, et al. Fumonisin B2 production by Aspergillus niger in Thai coffee beans [J]. Food Additives and Contaminants, 2009, 26(1): 94-100.

[14]MAYURA K, PARKER R, BERNDT W O, et al. Ochratoxin A-induced teratogenesis in rats: partial protection by phenylalanine [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1984, 48(6): 1186-1188.

[15]ABRUNHOSA L, MORALES H, SOARES C, et al. A review of mycotoxins in food and feed products in Portugal and estimation of probable daily intakes [J]. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2016, 56(2): 249-265.

[16]徐丹, 雷嬌, 康敏, 等. 真菌对黄曲霉毒素B1污染的防治研究[J]. 中国微生态学杂志, 2016, 28(2): 234-239.

[17]ROLAND A, BROS P, BOUISSEAU A, et al. Analysis of ochratoxin A in grapes, musts and wines by LC-MS/MS: First comparison of stable is otope dilution assay and diastereomeric dilution assay methods [J]. Analytica Chimica Acta, 2014, 818: 39-45.

[18]GARMENDIA G, VERO S. Occurrence and biodiversity of Aspergillus section Nigri on ‘Tannat grapes in Uruguay [J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2016, 216: 31-39.

[19]GELDERBLOM W C A, JASKIEWICZ K, MARASAS W F O, et al. Fumonisins-novel mycotoxins with cancer-promoting activity produced by Fusarium moniliforme [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1988, 54(7): 1806-1811.

[20]MARILENA B, LOREDANA C, ALAN D W, et al. A saccharomyces cerevisiae wine strain inhibits growth and decreases ochratoxin A biosynthesis by Aspergillus carbonarius and Aspergillus ochraceus [J]. Toxins, 2012, 4 (12): 1468-1481.

[21]楊学威, 段雪荣, 卢新军, 等. 关于葡萄酒中赭曲霉毒素A的研究进展[J]. 中国酿造, 2012, 31(11): 12-14.

[22]JOHN P. Mycotoxins: Fumonisins [J]. Encyclopedia of Food Safety, 2014, 2: 299-303.

[23]ZHONG Qiding, LI Guohui, WANG Daobing, et al. Exposure assessment to ochratoxin A in Chinese wine [J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2014, 62(35): 8908-8913.

[24]ZOLLNER P, MAYER-HELM B. Trace mycotoxin analysis in complex biological and food matrices by liquid chromatography-atmospheric pressure ionization mass spectrometry [J]. Journal of Chromatography A, 2006, 1136(2): 123-169.

[25]COVARELLI L, BECCARI G, MARINI A, et al. A review on the occurrence and control of ochratoxigenic fungal species and ochratoxin A in dehydrated grapes, non-fortified dessert wines and dried vine fruit in the Mediterranean area [J]. Food Control, 2012, 26(2): 347-356.

[26]TERRA M F, PRADO G, PEREIRA G E, et al. Detection of ochratoxin A in tropical wine and grape juice from Brazil [J]. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 2013, 93(4): 890-894.

[27]PONSONE M L, COMBINA M, DALCERO A, et al. Ochratoxin A and ochratoxigenic Aspergillus species in Argentinean wine grapes cultivated under organic and non-organic systems [J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2007, 114(2): 131-135.

[28]BELLI N, BAU M, MARIN S, et al. Mycobiota and ochratoxin A producing fungi from Spanish wine grapes [J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2006, 111(S1): S40-S45.

[29]BELLI N, BAU M, MARIN S, et al. Contamination by moulds of grape berries in Slovakia [J]. Food Additives and Contaminants, 2010, 27(5): 738-747.

[30]JIANG Chunmei, SHI Junling, ZHU Chengyong. Fruit spoilage and ochratoxin a production by Aspergillus carbonarius in the berries of different grape cultivars [J]. Food Control, 2013, 30(1): 93-100.

[31]QI Tianyu, RENAUD J B, MCDOWELL T, et al. Diversity of mycotoxin-producing black Aspergilli in canadian vineyards [J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2016, 64(7): 1583-1589.

[32]SOMMA S, PERRONE G, LOGRIECO A F, Diversity of black Aspergilli and mycotoxin risks in grape, wine and dried vine fruits [J]. Phytopathologia Mediterranea, 2012, 51 (1): 131-147.

[33]CHRISTOPHER D J, AMANDA B, AARON Z W, et al. High incidence and levels of ochratoxin A in wines sourced from the United States [J]. Toxins, 2017, 10(1): 1-12.

[34]JIANG Chunmei, SHI Junling, CHEN Xianqing, et al. Effect of sulfur dioxide and ethanol concentration on fungal profile and ochratoxin a production by Aspergillus carbonarius during wine making [J]. Food Control, 2015, 47: 656-663.

[35]SUN Xianyu, NIU Yuxue, MA Tingting, et al. Determination, content analysis and removal efficiency of fining agents on ochratoxin A in Chinese wines [J]. Food Control, 2016, 73: 382-392.

[36]李倩倩, 王華, 徐春雅, 等. 加速溶剂萃取-高效液相色谱法测定葡萄酒中赭曲霉毒素A的方法研究[J]. 中国酿造, 2009(4): 137-140.

[37]谢春梅, 李倩倩, 王华. 固相萃取法萃取葡萄酒中赭曲霉毒素A的方法研究[J]. 西北农林科技大学学报, 2008, 36(12): 187-191.

[38]何云龙, 梁志宏, 许文涛, 等. 葡萄中碳黑曲霉的分离及其产生赭曲霉毒素A的研究[J]. 中外葡萄与葡萄酒, 2009(1): 4-8.

[39]BRAGULAT M R, ABARCA M L, CABANES F J. An easy screening method for fungi producing ochratoxin A in pure culture [J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2001, 71(2/3): 139-144.

[40]PANTELIDES I S, ARISTEIDOU E, LAZARI M, et al. Biodiversity and ochratoxin A profile of Aspergillus section Nigri populations isolated from wine grapes in Cyprus vineyards [J]. Food Microbiology, 2017, 67: 106-115.

[41]PERRONE G, MULE G, SUSCA A, et al. Ochratoxin A production and amplified fragment length polymorphism analysis of Aspergillus carbonarius, Aspergillus tubingensis, and Aspergillus niger strains isolated from grapes in Italy [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2006, 72(1): 680-685.

[42]BATTILANI P, BARBANO C, MARIN S, et al. Mapping of Aspergillus section Nigri in southern Europe and Israel based on geostatistical analysis [J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2006, 111(S1): S72-S82.

[43]BEJAOUI H, MATHIEU F, TAILLANDIER P, et al. Black Aspergilli and ochratoxin A production in French vineyards [J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2006, 111(S1): S46-S52.

[44]LEONG S L, HOCKING A D, PITT J I, et al. Australian research on ochratoxigenic fungi and ochratoxin A [J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2006, 111(S1): S10-S17.

[45]SOMMA S, PERRONE G, LOGRIECO A F. Diversity of black Aspergilli and mycotoxin risks in grape, wine and dried vine fruits [J]. Phytopathologia Mediterranea, 2012, 51(1): 131-147.

[46]PERRONE G, GALLO A. Mycotoxigenic fungi [M]. New York: Springer, 2017: 33-49.

[47]ABARCA M L, BRAGULAT M R, CASTELL, et al. Ochratoxin A production by strains of Aspergillus niger var. niger [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1994, 60(7): 2650-2652.

[48]TANIWAKI M H, PITT J I, TEIXEIRA A A, et al. The source of ochratoxin A in Brazilian coffee and its formation in relation to processing methods [J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2003, 82(2): 173-179.

[49]GARCA-CELAE, CRESPO-SEMPERE A, GIL-SERNA J, et al. Fungal diversity, incidence and mycotoxin contamination in grapes from two agro-climatic Spanish regions with emphasis on Aspergillus species [J]. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 2015, 95(8): 1716-1729.

[50]PALUMBO J D, OKEEFFE T L, Ho Y S, et al. Occurrence of ochratoxin A contamination and detection of ochratoxigenic Aspergillus species in retail samples of dried fruits and nuts [J]. Journal of Food Protection, 2015, 78(4): 836-842.

(責任编辑:田 喆)