Transference of Things Remote:Constraints and Creativity in the English Translations of Jin Ping Mei

2020-12-17LintaoQI

Lintao QI

Monash University

Abstract The challenges JPM (Jin Ping Mei) imposes upon its English translators are manifold:not only is it from a different linguistic and cultural territory,but it also represents a literary genre which has long been rendered obsolete,depicting a social picture which is remote to the translators both spatially and temporally.The distance between the archaic ST (source text) and contemporary target culture imposes dramatic challenges upon the English translators of JPM,who may,however,exercise their creativity to confront or circumvent the various issues.This article will examine the constraints from the linguistic,literary and cultural aspects of the ST,and the translators’ creative solution in devising their TTs (target text).It is clear that the constraints in translation are always the motivating factor for translators’ creativity,and the otherness in the ST should not and would not discourage its transference across temporal and spatial borders into another language and culture.

Keywords:Jin Ping Mei; English translation; constraints; creativity; Clement Egerton; David Roy

1.Introduction

The challenges JPM imposes upon its English translators are manifold:not only is it from a different linguistic and cultural territory,but also it represents a literary genre which has long been rendered obsolete,depicting a social picture which is remote to the translators both spatially and temporally.Language evolves,culture progresses,and literary tradition is always in the middle of novice development.While any interlingual translation of contemporary literary work is by no means an easy task,it is a doubly daunting one if the work awaiting translation is from a distant culture and the remote past.The situation that confronts the 20th century English translators of JPM is illustrative of this respect:Firstly,the linguistic,cultural and literary conventions in the birthplace of JPM have changed almost out of recognition over the course of history; secondly,the social milieu that gives the novel its currency is difficult,if not impossible,for modern English readers to access.This article will examine the constraints from the linguistic,literary,and cultural aspects of the ST,and the translators’ creative solution in devising their TTs.The examination,though not possibly exhaustive—owing to the multitude of topics within the capacity of the million-word opus,will try to be selective but representative.

2.Implications of unique orthographical features

It was as recent as the mid-1950s when the Modern Chinese writing system in China officially adopted the same convention as English,starting from left to right horizontally (Seybolt & Chiang,1979,p.388),though isolated anterior experiments had been made in the early twentieth century.Notwithstanding this change,as a representative work of classic Chinese novel,JPM is written in the traditional form,starting from right to left vertically.It is not likely that any English translators of the novel before the 1950s have access to a copy of the ST typeset horizontally,and after this date,the only known English translator of it,Roy,bases his rendition on a reprinting of the Ming edition of JPM.Therefore,the orthographical feature of the ST opens up yet another dimension of discussion for its English adventure.Explanations about the orthographical differences between languages vary,but De Kerckhove’s survey in hisThe Skin of Cultureis intriguing and revealing:

All writing systems that represent sounds are written horizontally,but all systems that represent images,like Chinese ideograms or Egyptian hieroglyphs,are written vertically.Furthermore,the vertical columns of imagebased systems generally read right to left.[…] All writing systems,except for the Etruscan,are written to the right if they contain vowels.All systems without vowels are written to the left.(de Kerckhove & Dewdney,1997)

De Kerckhove goes on to elucidate the revolutionary effects of the alphabet on the Westerners’brain and their world,saying the alphabet also affects the organization of thought of its users.The same argument,however,is not less applicable to the ideographic writing system.Therefore,any undertaking to deal with the two disparate writing systems will necessarily be a wrestling between two modes of thinking,and conversion from one into the other naturally sets up a battlefield for them—and for the translator.

The battle betrays one deficiency of Jacobson’s tripartite division of translation.Take English translation of JPM for example,the translation is certainly an interlingual one,but the disparity between the two systems will easily warrant it a label of “intrasemiotic” translation.Given that both can be categorized as written signs,the replacement of ideographs with alphabets simply renders every part of the former out of recognition spatially,visually,and perceptively.By contrast,translation within the same linguistic family—say from German into English—does not usually result in such radical changes.To be sure,it is an equal,if not more,formidable task,but the fact that nearly each part of words is still recognizable gives the words a similar status as the newly coined English words which are yet to be learned by the reader.

Translation entails first and foremost the conversion of a text from one written sign into another,which has been so taken for granted that people seldom examine the popular concepts in translation studies in this context.In fact,the change of writing system involved in translation as exemplified by the English rendition of JPM,implies that translating activity is by nature a domesticated one.In other words,no translated text deserves criticism on the grounds of domestication,regardless of the direction of rendition—either from a major language or a minority one; either from a dominating language or a dominated one; what people have been accusing of some TTs should be better branded over-translation.No English translator of JPM has arranged,and none would,I believe,even think of arranging their TT in the way the ST is presented orthographically,as the two writing systems are simply incompatible in that respect.

Paradoxically,all translation will have to be,by definition,foreignized as the translators are,without exception,always “in two minds”.Just as De Kerckhove believes of the alphabet having its imprint on users’organization of thought,Humboldt has famously argued that “there resides in every language a characteristic world-view” (Losonsky,1999,p.216).As a result,in the process of transferring from Chinese into English,which is seldom an uneventful one,the translator of JPM inevitably immerses him/herself in both the SL and the TL.As a bilingual,he/she is variably influenced by both,but solely attached to neither because the acquisition of a language is a package deal—the worldview inhabited in the language is not for sale,and the learner has to take the gift,willy-nilly.Once endowed with the way of thinking a language entails,it is no longer possible for the bilingual translator to think outside it—it is a one-way street.The translator still has the freedom to decide his/her preference between the two systems,but it is not within his power to stay fully independent of either language/world-view any more.The resultant TT will reflect that initial conflict,constant struggle and final hybridity,thus trace of foreignization is an inherent part of any translation.The translator,as a result,finds him/herself familiar with both languages,but at home in the field of neither,becoming a migrant in the space of the SL and an exile in the space of the TL,in other words,living in a space of in-betweenness,which is undefined,undetermined and unstable.

3.Translation of proper names

To illustrate the paradox in practice,I will take the translation of proper names as an example.As Hermans(1988,p.14) says,“In its strongest form […] the translational norms underlying a target text as a whole can in essence be inferred from an examination of the proper names in that text.” Orthographically,the translated names of the Chinese characters will have to be a marriage of domestication and foreignization:the conversion of ideographic transcript into alphabetical system renders the names accessible in the TT,but their phonetic eccentricity to the ears of the TL readers serves as a constant reminder of the foreign origin of the text.As for the actual translation,it is not surprising to find that the translators “do not always use the same technique with all the proper names” (Nord,2003,p.183).What an examination can reveal is a mere tendency of the translatorial preference for one or the other,because cohabitation of the two in any TT is the rule.

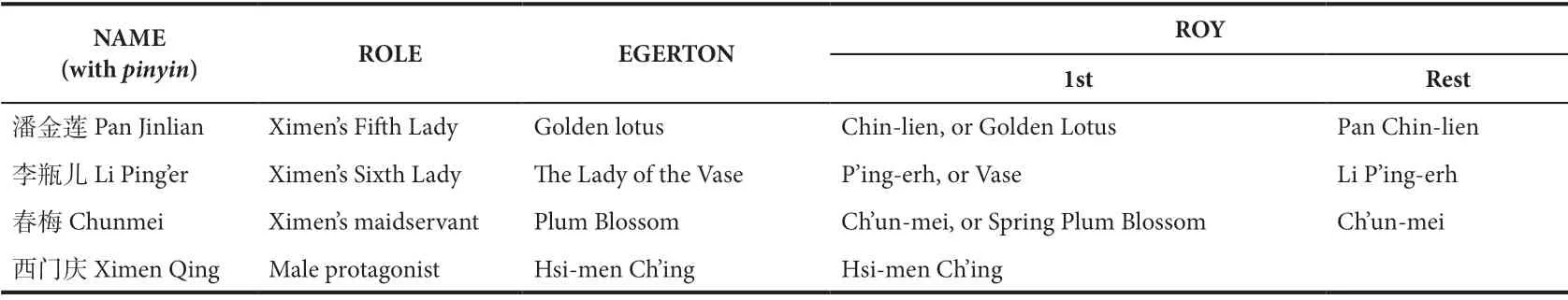

In the table below,as a snapshot,I list the names of Roy and Egerton’s translation for the male protagonist along with the three heroines from which the novel derives its title.

Table 1 The list of the names from Jin Ping Mei

Egerton follows a practice of translating the sense of the female names and the sounds of the male names,which is by no means Egerton’s invention:

Through the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century,English translators of Chinese fiction regularly Romanized the names of male characters while translating the names of all women and girls,ostensibly to make identification easier for readers unfamiliar with Chinese transliterations.(Hegel,2011,p.19)

Although the majority of the character names inJPMhave meanings,the reading of the ST only gives a surface recognition of the sound of the name; it is the further subjective interpretation that reveals to its reader the sense level.By strictly following this established practice,which creates extra semiotic signification of differentiating genders of the characters,Egerton’s translation of names is able to achieve the effect of balance and consistency.However,if he is working with the presumption that all readers know what he is doing with the Chinese names,he risks misleading innocent readers into the illusion that Chinese men have different forms of names from women.It is true that female names tend to use lexical units denoting such feminine qualities as beauty and gracefulness (Liu,1996,p.93),and they are more ready to lend themselves to pretty senses like “Golden Lotus” or “Plum Blossom”.Failure to convey their semantic meanings is definitely a pitiful loss.However,the mere concentration on the sense layer of female names is also overdoing the trick.A possible consequence could be that readers with a feminism perspective may accuse Egerton of erasing the female characters’ identity by reducing them to a group of fancy noun phrases.

Notwithstanding,the practice of semantic translation of names is not totally missing in Roy’s TT.The first three female characters listed above get their names transferred into English in the form of a transliteration accompanied by a semantic translation at an early stage,with the semantic translation as a means of in-text translatorial comment,as is exemplified by “Chun-mei,or Spring Plum Blossom”.And after their initial appearances,all the names are referred to by their sounds alone.This suggests that to Roy,adherence to the SL sound is predominant.However,he attempts to compensate for the loss of meaning by at least providing a reminder to the reader.

So far as the semantic translation of the female names is concerned,Egerton’s translation demonstrates an overwhelming tendency of domestication,while Roy’s displays that he prioritizes foreignization.But when it comes to the translation of male names,this difference in preference disappears:both opt for transliteration.1Exceptions exist in Roy’s TT:transliteration plus semantic translation for a few male names is still to be found,e.g.“Ying Po-chueh,or Sponger Ying” for the first appearance of the name 应伯爵.Even in this seemingly straightforward aspect,translator’s creativity is constrained by his contemporary social context,which,ironically,originates from the ST end.

In the two TTs,transliterations of such names as “Hsi-men Ch’ing” are identical as they employed the same Wade-Giles Romanization system,“the dominant scheme for representing the standard pronunciation of Chinese” (Hegel,2011,p.19) until around 1980.This system is superseded by thepinyinsystem,“the official system of Romanization of the People’s Republic of China,which is recognized as the ISO international standard” (Lowe,2010,p.xxiv).The phonetic transcription provided in the leftmost column of the tables in this article is inpinyin.For Egerton,there is no other alternative than Wade-Giles system for transliteration as the idea of thepinyinsystem is nonexistent before the 1950s and it takes decades for it to get matured and recognized.But for Roy,it is obviously a matter of choice:the two systems are in a state of co-existence when he started his translation in the early 1980s.Roy so defends his adoption of the older system:“At the time I did my research and started on my translation,the Wade-Giles system of transliteration was still that most commonly used in the English speaking world.”2Personal communication with Roy on 27th September,2012.

However,the three decades Roy spent on his translation have seen the Wade-Giles system run out of date and thepinyinsystem come to the fore,which renders Roy’s version a little bizarre to modern readers who are more accustomed topinyin.Nevertheless,having started with the Wade-Giles convention,Roy “felt it necessary to continue to use the system […] in order to be consistent.”3Personal communication with Roy on 27th September,2012.

Roy’s free choice of the earlier Romanization system seems to implicate that the constraint,in this case,is limited,but the force of the Romanization system is actually absolute.The existence of such a system is in itself an effort to compromise the chasm between the two languages,and the use of it in the English translation of Chinese works,though intends to domesticate the exotic so that the TL reader can understand,actually foregrounds the otherness of the text concerned.When that system is replaced by another,the translation activity is also expected to reflect that change.If,as in Roy’s case,the translator for whatever reason failed to accommodate the change,his TT runs the risk of being considered archaic even before its completion by the new generation of TL readers who are acquainted with the newpinyinsystem.

Indeed,even the creative work of the previous generation of translators is subjected to the constraint imposed by this change.Quite recently,many translations of classic Chinese novels which initially adopted Wade-Giles convention have been converted into thepinyinsystem of Romanization in their reprintings.Following Antony Yu’s (2006,p.xiv) decision to usepinyinfor the abridged version of his translationXi You Ji (The Journey to the West),the recent reprinting of Joly’s (Lowe,2010,p.xxiv) translation ofHong Lou Meng (The Dream of the Red Chamber)which was first published in the late 19th century and Egerton’s(Hegel,2011,p.19) translation—The Golden Lotushave also been revised using thepinyinsystem.It is not unlikely that Roy’s transliteration would also be switched topinyinshould it be republished.

Carrying proper names in a SL across to a TL may as well be regarded as a paradox of translation.Some of Pym’s (1992,p.78) discussion concerning transliteration of names could be extended to talk about the translation of proper names in general:it should be regarded neither as “an automatic index of untranslatability”,nor as “a sign of universal comprehension”.Translators are thus always working in a state of constant compromise,struggling between assimilating and preserving the refractory exoticness of the names.Proper names,in my opinion,will remain eternal strangers in their migrated TT,however hard the translator has tried to bring it in line with the TL convention.

To complicate the picture,in the process of converting the Chinese names into English,another typographical feature which is compulsory in the TL yet foreign to the SL is going to demonstrate its creative force:when the Chinese ideograms are translated into alphabets,a proper name ascends to a more prominent position as a lexical unit in the text/context.As Chinese writing system is void of editorial marks such as capitalization or italics to distinguish proper names from common nouns (Foley,2009,p.52),their existence in any context is not marked,but when translated into English,they immediately stand out from the surrounding text/context through capitalization of their initial letters,making it easier for them to be identified in their new linguistic milieu.

4.Role of punctuation marks in translating JPM

Being conversant with two languages enables the translator to personally appreciate the literary work in both and creatively transfer it from one into the other,rendering the ST comprehensible and his creativity appreciable by those TT readers who have no access to the SL.However,what is not readily visible to the reader—even to the translator him/herself—is that right from the outset of the translating activity,the translator is doubly constrained by the revolutionary forces of the two languages.This is much clearer if evaluated in combination with other orthographic features like punctuation.

In the west,word-spacing was introduced in the seventh century and finalized in the tenth,while punctuation marks were standardized around sixteenth century thanks to the printing industry (Bernstein,1977,p.38).In addition to its ability to indicate grammatical and phonological structure (Cook,2004,p.1),punctuation is popularly known for its rhetorical value,instrumental in conveying the style of individual writers (Dawkins,1995; Petit,2003).For English translators who have taken punctuation marks in written texts for granted,the absence of them in their ST of JPM represents yet another challenge.

The unpunctuated Chinese ST is apparently an open space for reading.Physically,it does have its closed,independent textual territory,but once it is subjected to reading,the plurality of interpretation resulting from different ways of punctuating renders its textual boundary theoretically indefensible.Readers come from diverse backgrounds,purposes and ethos,and naturally leave with their equally diverse interpretations which are personalized and “punctuated”.The same reader,when entering and reentering the textual space,is unlikely to punctuate the whole text exactly the same,and will therefore keep revisiting,revising,or reversing his/her previous interpretation.Much less when it comes to readers of the text from different historical periods,or from remote linguistic and/or cultural soil.

The text,representing the intention of its author at the time of his/her writing,which detaches from the text or becomes irrelevant to it once the product is born,is forever one and the same,but each reading is an attempt to re-present it in the reader’s own language with his/her own experience of the world.General consensus is humanly possible within a community at a certain historical period,but fresh reading comes into the picture from time to time when the reader comes from different linguistical or cultural time and space.Hermeneutically,“truth is only found dialectically,in a discussion process within a group,valid for a certain period of time,ever remaining open for new interpretation” (Stolze,2010,p.143).In translating JPM into English,however,the indeterminacy of the ST owing to the absence of punctuation marks is not possible to transfer.What gets transposed into the punctuated TT is the somewhat fixed representation of the ST as projected by the translator’s interpretation (any attempt to punctuate of the ST is already an action of translation,and any ensuing interpretation is therefore based on a previous translation).If,as De Man contends,every reading is necessarily a misreading (Selden et al.,2005,p.172),and no one is in a better position than the translators to evaluate which version is right or wrong,highlighting the difference between multiple TTs can still exemplify the creative side of the translators’ work.

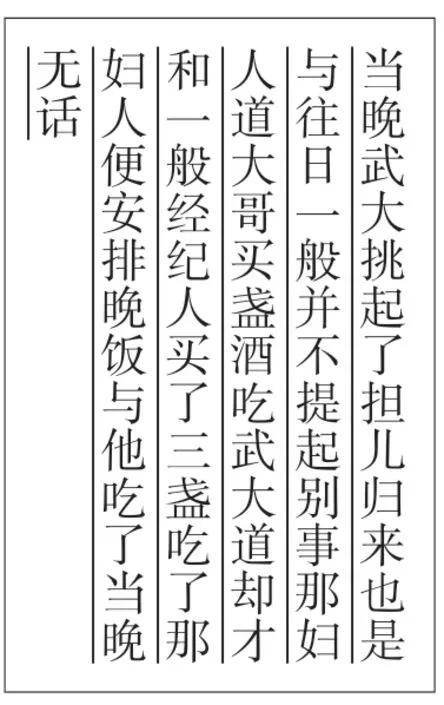

Egerton’s TT:

This evening,when Wu Ta came home with his baskets and said nothing,as was usual,she asked him to have some wine.He refused,saying he had already taken wine with some merchants.She laid out his supper,but still he did not offer to speak.(Lanlingxiaoxiasheng,2008,p.78)

Roy’s TT:

That evening when Wu the Elder came home,shouldering his carrying pole,he acted just the way he always did and didn’t bring anything up.

“Darling,” said the woman,“how about a cup of wine?”

Her delicious meals and quiet smile graced the cabin with a wonderful woman s touch. But the wrong woman, Edward mourned as he collapsed9 onto his cot each night. Why did they send Marta? Would he ever see Ingrid again? Was his lifelong dream to have her as his wife forsaken10?

“I’ve just had three cups with another vendor,” said Wu the Elder.

The woman then prepared supper and they ate it together.Of the events of that evening there is no more to tell.(Langlingxiaoxiaosheng,1993,p.99)

The way the TTs are punctuated has rich implications.Firstly,the dismissal of quotation marks in Egerton’s version renders the text into a purely narratorial description of the event,while the employment of them creates in Roy’s translation a more dynamic and more interactive scene.That is to say,behind the superficial phenomenon of quotation marks,there are two distinct narratorial strategies,with each being made to speak for themselves:providing the reader with a vicarious report of the event,and inviting him/her to observe the characters directly.The variation here also gives rise to a second typographical fact:differing paragraphing.With his third-person retelling,Egerton was able to relate the story within the capacity of one paragraph; but Roy’s use of quotation marks necessitates the division of paragraphs to achieve the natural flow and clarity of narration.

Furthermore,the two versions also reveal that the two translators differ not only in their choice of which punctuation marks to use,but also in how to fragment the ST,i.e.where should the punctuation come in.The last sentence in Egerton’s TT reads “but still he did not offer to speak”,whose counterpart in Roy’s text is “Of the events of that evening there is no more to tell.” In the former,“他 (he)” in the ST is taken for the subject of “无话 (had nothing to say; said nothing)”,while in the latter,“当晚无话 (About that evening there is nothing to say)” is regarded as a tag expression of the Chinese storyteller,which tends to win general approval from modern Chinese readers.However,the two interpretations,disparate as they are,both make smooth reading,enabling a natural transition in the context.It may indeed be a constraint to translate an unpunctuated novel,but depending on the reader’s major concern in their reading,the translators will creatively work out of the ST dissimilar yet equally valid good stories.Anyway,on the road of seeking the truth of the ST,not one reader is more privileged or more innocent than another.Therefore,no representation is more valid than others; all TTs resulting from serious efforts to re-present the ST should be valued.Particularly when the ST is one whose historical context has long died,general consensus does not naturally legitimize the TTs conforming to it and should not be employed to suppress those that diametrically oppose it.In the area of humanity,sometimes even in natural sciences,general consensus changes over time and common sense may sometimes mislead.

5.Making sense of the archaic:Allusive use of names

Like other literary forms,poetry is also a happy marriage of language and culture.For competent bilinguals,it is not unusual to come across “words or phrases that are so heavily and exclusively grounded in one culture that they are almost impossible to translate into the terms […] of another” (Robinson & Kenny,2012,p.175).These kinds of “words and phrases” have recently been termed “cultural bumps”.Coined by Archer (1986,pp.170-171) referring to problems that arise from interacting with people of different cultural backgrounds,the term “cultural bump” is later extended by Leppihalme (1997,p.viii) to situations describing the “culturebound elements” that “hinder communication of meaning to readers in another language culture”.To translators,cultural bumps range from culture-specific items to rhetoric devices like similes and allusions.In consideration of space,this section will be limited to the study of the allusive use of names in JPM.

Allusions,though mainly employed as a literary device,owe their contents and vitality to the life of people,often in its remote past.In this regard,to appreciate allusions from another culture isipso factoto make sense of the life of other people.Similar to its counterpart in the West,the Chinese poetry has its“body of myths and legends” to draw upon,and is “especially fond of employing allusions to the famous events and personages of the nation’s lengthy past” (Watson,1984,p.2).This is an observation which will easily win popular consensus,but to the translators of classical Chinese poetry,it is not more than an understatement.As a corroboration,I felt compelled to quote Hart (1938,p.23) at length:

At first an ornament to the poem and a joy to the reader,classical allusion and epithet became so numerous and obscure as to require concordances and encyclopaedias for their elucidation.With decreasing fertility of imagination and increasing inflexibility of form,these allusions become so burdensome that they destroyed the joy of reading poetry.Employed by the poetaster to display his erudition,their niceties and studied obscurities finally cramped,crushed,and destroyed the Chinese poetical genius.

In the final centuries of the Chinese feudal history,when JPM was written,creativity was gradually suffocated to death in classic versification,for which the fastidious interest in the utility of allusions is largely to blame.JPM was at once a witness and victim of this interest.My concern in this section,however,is not as much to unravel the demise of classic Chinese poetry but to investigate how Egerton and Roy are going to survive the fatal allusions that once devastated “the Chinese poetical genius”.

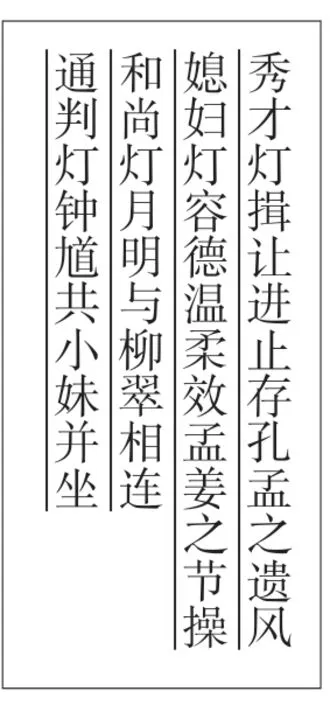

Egerton’s TT:

Student lanterns,bowing back and forth,attentive to the bidding of Confucius and Mencius.

Wife lanterns,tender and obedient,picturing the virtues of Meng Chiang.

Monkish lanterns,with Yüeh Ming and Liu Ts’ui standing side by side.

Lanterns of the Scribe of Hell,Chung K’uei and his sister,sitting down together.

(Lanlingxiaoxiaosheng,2008,p.355)

Roy’s TT:

Scholar lanterns,

Bow and scrape,advance and retreat,

Preserving the manners of Confucius and Mencius;

Housewife lanterns,

Display virtuous demeanours and gentle dispositions,

Emulating the fidelity and resolve of Meng Chiang.

There is a Buddhist monk lantern,

Depicting Yüeh-ming and the courtesan Liu Ts’ui;

And an underworld assessor lantern,

Showing Chung K’ueiseated with his little sister.

(Lanlingxiaoxiaosheng,1993,p.301)

Endnotes of Roy’s TT:

6.Meng Chiang is the heroine of one of the best-known Chinese legends,which is more than two thousand years old and exists in innumerable forms.Basically it is the story of a wife whose grief for her dead husband is so great that it causes the wall in which he has been buried to crumble so that she is able to find his bones and take them home for burial.See,e.g.,Meng Chiang nüpien-wen,inTun-huangpien-wen chi,1:32-35; and Waley,Ballads and Stories from Tun-huang,pp.145-49.

7.This famous story in which the Buddhist monk Yüeh-ming induces the enlightenment of the courtesan Liu Ts’ui exists in more than one version.SeeYüan-ch’ühsüan,4:1335-52; and the middle-period vernacular story entitledYüeh-ming Ho-shangtu Liu Ts’ui(The Monk Yüeh-ming converts Liu Ts’ui),inKu-chin hsiao-shuo,vol.2,chüan29,pp.428-41.

8.Chung K’uei is the principal demon queller of Chinese popular tradition.According to the most common version of the legend,he committed suicide after having been unjustly rejected in the imperial examinations because of the extreme ugliness of his appearance.Later he appeared to the emperor in a dream and demonstrated his prowess at quelling demons,as a result of which he was duly put in charge of that function.In some versions of the story,even after his suicide he arranged the marriage of his younger sister to the benefactor who had paid his way to the capital to take the examinations.For further information on this subject,see Ma Shu-t’ien,Hua-hsia chu-shen(The various gods of China) (Peking:Pei-ching Yen-shanch’u- pan she,1990),pp.265-79.

(Lanlingxiaoxiaosheng,1993,p.519)

The excerpt above is from a prose poem that is used to describe the various lanterns during a celebration of the traditional Lantern Festival when they are hung everywhere in the city so that people can enjoy the sight of them in the evening.Though the arrangement of lines into couplets is one salient feature of the excerpt,it is the density of allusions that are more conspicuously responsible for the elegance and literaryism of the description.

Allusions,says Leppihalme (1997,p.ix),“have meaning in the culture or subculture in which they arise but not necessarily in others”.For example,when allusions are made to historical personages,translators will have no way to circumvent the problem but to confront it,pure and simple; and there is not much room for textual adjustment,as is demonstrated by the two English versions above.Differences between the two TTs in terms of phraseology are significant,but my attention here will be solely on the translation of allusive texts.

First of all,allusions vary in their degree of familiarity to the TL readers—it might as well be the case with the SL readers.So stupendous is the vitality of some allusions that they outlive the time and space that gives birth to them and perpetuate in a transnational canonical status.“Confucius” and “Mencius”are two such examples,and both translators are easily justified for their treatment with these two allusive usages.Then,there are some other allusions that may even be problematic to the ST readers.This is a phenomenon also observed by Knechtges (1995) in his teaching of classical Chinese literary works,“modern Chinese students […] have almost as much difficulty understanding and explicating the text as their non-Chinese counterparts” (p.46).On occasions like these,“some degree of explanation” from the translator is definitely needed to make them “intelligible” (Watson,1984,p.3).“Yueming” and “Liu Cui”in the above poem might be classified into this category.However,the vast majority of allusions belong to a third group sitting in between the previous two:they are neither canonically intelligible nor universally incomprehensible; they may only challenge the TL readers yet impose no problem on the SL audience in terms of intelligibility.Terms like “Meng Jiang” and “Zhong Kui” may be safely subsumed under this category.In translations,translatorial intervention is again expected as regards these allusions; otherwise,the resultant TT,though grammatically flawless,would sound nonsensical.The simple reason is that the text is carried over into the TL,but the intertext from which it derives its life is lost.To some extent,a TT of an allusive text without translatorial explanation is a piece of lifeless composition which has been deprived of its power of communication.

Allusions partake of strong intertexual relations which constantly challenge translators.As Venuti(2009,p.159) sees it,a mere “close rendering of the words and phrases” cannot reproduce the intertexual relations of the ST.Phrases like “Yueming” and “Liu Cui”,in Enkvist’s (1991,pp.7-8) terms,are semantically“comprehensible” to anyone with basic command of English,yet not necessarily “interpretable” on the pragmatic level because they fail to carry the intertexual relations over to the TT.So when allusions become enigmas to the TL readers,it is the translator’s choice to put them off with a mere linguistically correct translation,or to save himself the trouble by leaving them out,or responsibly undertake the extra task of improving the reader’s source culture literacy by reproducing the intertextuality,at least in part.One possible way,suggests Venuti (2009,p.159),is the employment of paratextual devices.

This recommendation is strongly supported by Roy’s practice.In his translation,in order to make the allusions pragmatically “interpretable”,Roy supplements his TT with ample endnotes sharpshooting the legends behind the allusive names and enumerating the sources of these stories.If the cursory knowledge of the stories is indispensable to a full appreciation of the allusions,the existence of their sources in the notes,obviously,cannot be assessed as such.This is a potential risk of Roy’s choice to the readership of his TT:the interest of general readers is in the pleasure of reading a good story.When notes and explanations are absolutely necessary,they would appreciate if the translator could keep them to a minimum.In Roy’s three endnotes listed above,the first half meets this reader expectation fairly well:the stories are summarized in condensed language,and the points related to the poem are highlighted.This,without doubt,benefits from Roy’s conversancy with the repertoire of the Chinese literature.The second half of the endnotes,however,are apparently not directed to the general readers who,more often than not,would have little interest and less patience in learning about the sources of these stories; moreover,thepinyinand numerical data in Roy’s endnotes mean nothing more than a series of nonsensical symbols to those who are illiterate in Chinese.Obviously,the inclusion of the sources of the allusions stems from Roy’s researcherhabitus,which,in addition to equipping Roy with the facility for identifying the sources,convinces him of the value of such supplementary information.

However,his initial purpose of translation is not to scare ordinary readers off,much less to let nonspecialists feel excluded,so he annotates his TT the best he can to help readers better appreciate the novel.Readers could choose not to refer to the notes,but Roy firmly believes that for a work as sophisticated asJin Ping Mei,notes are essential.Over the years of his translation and review,he is not unaware of the discouraging effect of his seemingly superfluous notes,and he has it in mind to publish a version including only the informational notes while leaving out all the source stuff.1Personal communication with Roy on 18th June,2012.

Egerton’s translation,on the other hand,has few notes to say,but he is not oblivious of the need of them:

I have no doubt that a deliberately strictly literal translation,with an elaborate apparatus of notes and explanations,would be extremely valuable,but my interest in the book as a masterpiece of novel writing has made me try to render it in such a form that the reader may gain the same impression from it that I did myself.(Lanlingxiaoxiaosheng,1939,p.x)

There is no objection that Egerton has the freedom to make a translation which is non-literal and non-scholarly,even though he openly acknowledges his perception of the value of a strictly literal translation with an elaborate apparatus of notes and explanations,which,by the way,conjures up in every aspect of Roy’s TT.From a reader’s perspective,it is very hard for me to understand how can Egerton’s non-literal and non-scholarly translation make the reader “gain the same impression” from the novel as he does himself? It is true that Egerton tries to present his TT in smooth English,but as far as allusions are concerned,his non-literal and non-scholarly standard does not help a bit in creating in the readers’ mind“the same impression”.As a matter of fact,when thrown a miscellany of seemingly nonsensical foreign names,the frustrated readers like myself are more likely to expect their translator to help them out by some quick notes than to be kept helplessly uninformed.Therefore,by choosing not to provide notes to these allusions,Egerton virtually precludes his readers from gaining “the same impression” from the novel as he does,leaving the pleasure of reading exclusively to himself.At any rate,apart from the specialists,general readers read the translation because the ST is inaccessible to them; hence there is no justification for producing a TT that is as inaccessible.Egerton does say that it is not easy to “make a smooth English version and,at the same time,to preserve the spirit of the Chinese” (Lanlingxiaoxiaosheng,1939,p.vii); it may be hard to define “the spirit of the Chinese”,but incomprehensibility is certainly not part of it.

Being a popular and efficient means of compensating for the loss of intertexuality in a translation,notes are not the only instrument translators can appeal to.In the example above,Roy also utilizes in-text explication to facilitate reading experience and remove potential misunderstandings.The third line of the ST poem is rendered by Egerton as “Monkish lanterns,with Yüeh Ming and Liu Ts’ui standing side by side”,where the second name Liu Ts’ui is correctly transcribed,while the first name is a mistake:it takes Yüeh-ming together to comprise a given name of the monk,but Egerton surnames the monk Yüeh.This is pertinent to the cultural knowledge concerning Buddhism in China:the founder of Buddhism,Shakyamuni Buddha,is 释迦牟尼 (Shijiamouni) in Chinese; therefore,Buddhists in China are usually surnamed 释 (Shi)after him.A monk surnamed Yüeh is simply a cultural fallacy.Other than that,the English version reads smooth,but without notes and other assistance of any type,it is highly probable that the two persons in the line will both be interpreted as monks,which is not what the Chinese ST wanted to convey.

Roy surfaces the identity of Liu Ts’ui,who is not a monk,into the TT,putting the line into “There is a Buddhist monk lantern,Depicting Yüeh-ming and the courtesan Liu Ts’ui” and effectively ruling out any misinterpretation.By preserving all that is in the ST adequately and accurately in his TT,Roy is both loyal to his author and faithful to the text.By providing additional information to remove the culture bumps to smooth the way for readers,he establishes himself a responsible text producer and his text a scholarly translation.Since Yueming and Liu Cui are less well-known figures,they are not likely to be in the repository of knowledge of many modern Chinese readers.Roy’s performance in this regard,in my view,is praiseworthy even in the sense of helping those English-literate Chinese readers better appreciate their own literary heritage.

6.Concluding remarks

Though the decisions of both Egerton and Roy may not be satisfactory to all readers,the above discussions also reveal that they are never alone in their respective translatorial choices.The differences between Chinese and English as discussed in this article,and the difficulties they impose upon their English translations are constitutional and areipso factoindependent of the translational action.Due to the remoteness in time and space of language,culture,and literary genre,the archaic and sometimes obsolete features of the STs are destined to confront any English translators of classic Chinese novels.However,history proves that instead of being discouraged,translators are always embracing such massiveness of the otherness in the Chinese STs.It is precisely the curious otherness that has motivated translation and stimulated the creativity in the translators.As Rabassa (Weissbort & Eysteinsson,2006,p.509) astutely claims,“If a novel is universal,the universality should not be hindered by the strange.”

猜你喜欢

杂志排行

翻译界的其它文章

- Nominalization and Domestication:Reconsidering the Titles of the English Translations of Pu Songling’s Liaozhai zhiyi

- The Re-narrated Chinese Myth:Comparison of Three Abridgments of Journey to the West on Paratextual Analysis1

- Purpose-driven Texts and Paratexts:A Comparative Study of Three Retranslations of Xixiang ji

- The Language of Values in the Ming Novel Three Kingdoms1

- Filtration or Remolding:The Role of the Translator as an Intentional Mediator1

- Lessons from Compiling and Translating Homoeroticism in Imperial China:A Sourcebook