Nominalization and Domestication:Reconsidering the Titles of the English Translations of Pu Songling’s Liaozhai zhiyi

2020-12-17YukitCHEUNG

Yu-kit CHEUNG

Lingnan University

Abstract Since the publication of Herbert Giles’s first English translation of Pu Songling’s Liaozhai zhiyi entitled Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio in 1880,there have been at least eleven book-length English translations in the space of 140 years.Whilst there is obvious diversity in their translation strategy—some versions display more signs of domestication than others; their English titles are found to be invariably domesticated irrespective of the translation strategy therein—they are generally in line with the English tradition.It will be argued that,with the title being the first point of contact between the book and the reader,a domesticated book title has a role to play in securing the acceptability of the translation product on the English-speaking market.There will be four parts to the main body of this paper.The first is a descriptive report of the titles of Liaozhai zhiyi in the English versions,which is followed by a close reading of these titles in the next part,casting light on the nominalization of the Chinese title in the process of translation.The third part is an analysis of nominalization as domestication with reference to the yawning chasm between Chinese and Graeco-Roman world views.Attempts will be made in the last part to explain,with the aid of the Polysystem Theory,the preference for domestication in the titles of the English editions of Liaozhai zhiyi.

Keywords:title; domesticating; nominalization; Graeco-Roman culture; world view

1.Introduction

Paratext,in which the Greek suffixpara-means “beside” (Skeat,1882,p.370),has received close academic attention over the past two decades and has established itself as a new field of study in literature and translation.According to Batchelor (2018),there have been—in English alone—over 100 articles making explicit reference to this concept since 1996 (p.25),not to mention countless conferences dedicated to its exploration worldwide.

Extensively explored by Genette (1997) in his seminal bookSeuils,“the paratext is what enables a text to become a book and to be offered as such to its readers and,more generally,to the public” (p.1).It is “athreshold[…] that offers the world at large the possibility of either stepping inside or turning back”(Gnette,1997,p.2).To put it in a more concrete manner,Batchelor (2018),having marshalled various ideas in this key work of the French literary theoristin response to several queries she raises,summaries the notion of paratext as thus,“The paratext consists of any element which conveys comment on the text,or presents the text to readers,or influences how the text is received” (p.12).These components include titles,dedications,inscriptions,epigraphs,prefaces,etc (Genette,1997,pp.vii-x).

The title of a work is not only a name which provides information on “its subject,contents,or nature”(“title”,n.d.),but also somewhat an usher,guiding one into the world established in the novel,for,as literary critic-cum-novelist David Lodge (1993) explains,it “condition[s] the readers’ attention” (p.193),“bringing into sharper focus what the novel is supposed to be about” (p.194).As far as Pu Songling’s magnum opusLiaozhai zhiyicompleted in the spring of 16791This is the year indicated in the author’s preface to the collection.Although 1679 is widely considered the year of the completion of Liaozhai zhiyi when the author was forty years of age,it is agreed that Pu continued to expand his work well into his late years.is concerned,the verbzhi志 and adjectiveyi异 are the gateway through which the reader enters a world of the strange.Despite the importance of the title,it receives,as a rule for one reason or another,less academic attention than the main body of a literary text,if it is not aterra incognita.There is no exception as far as classical Chinese tales (xiaoshuo小说) is concerned.And one may even be surprised to find the comparative paucity of literature on the translation of titles in English academic discourse (Chan,1995,pp.557-559).

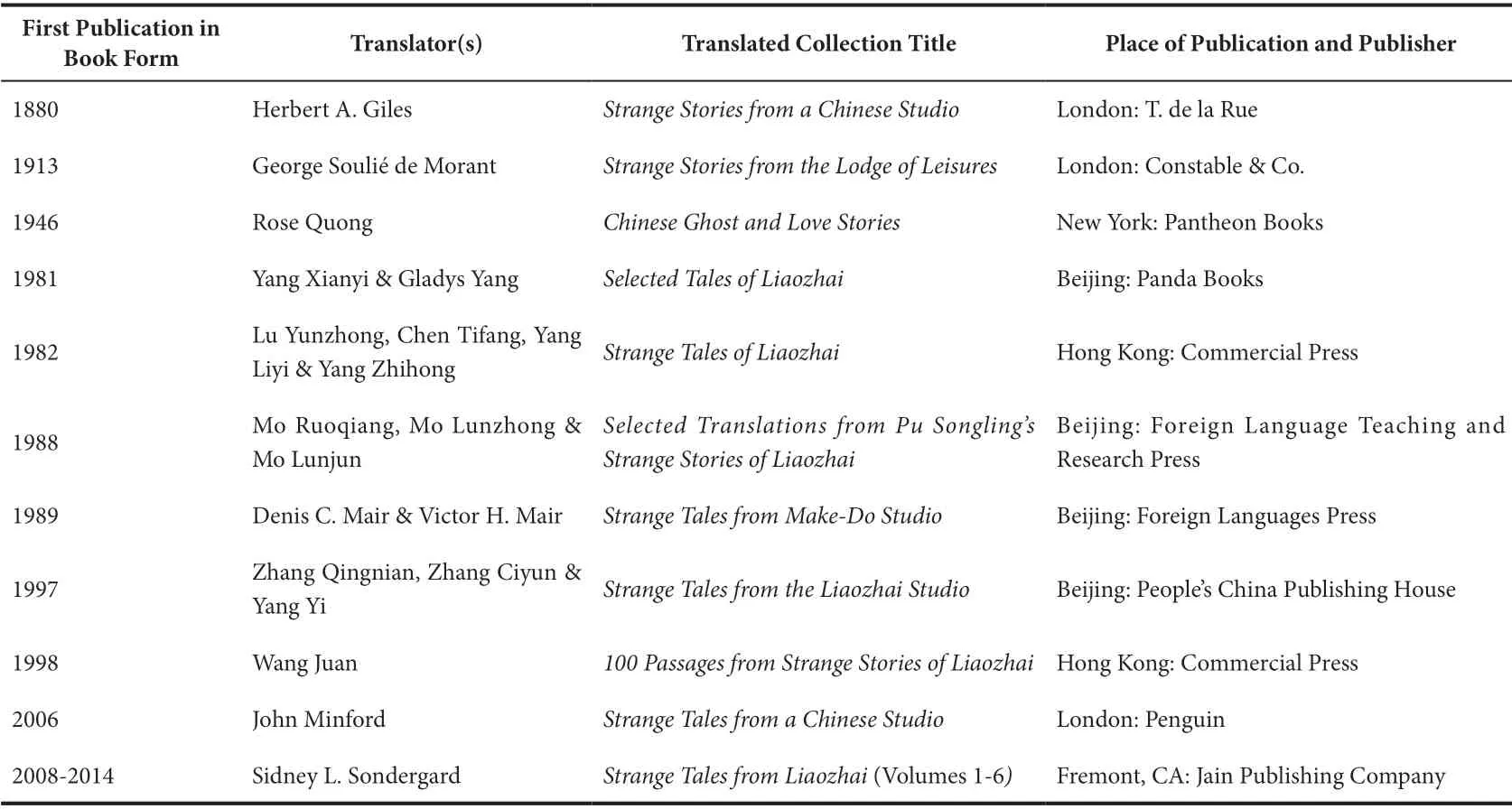

Since the publication of Herbert Giles’s first English translation ofLiaozhai zhiyientitledStrange Stories from a Chinese Studioin 1880,there have been at least eleven book-length English translations,including Giles’s,published in the space of 140 years (see Table 1).There have also been various anthologies of Chinese ghost stories,fairy tales,or Chinese literature in general,where a varying number of entries fromLiaozhai zhiyiare collected.For instance,there are threeLiaozhaitales in Stephen Owen’s(1996)Anthology of Chinese Literature,while entries fromLiaozhai zhiyimake up one-fourth of Moss Roberts’s (1979)Chinese Fairy Tales and Fantasies.

Table 1.English translations of Liaozhai zhiyi over the past century and a half

To be sure,in addition to the diversity in the selection of stories,the translation strategies are also various,and some editions display more signs of domestication than others along the continuum of strategies,although both domesticating and foreignizing strategies are expectedly found in every translation (Robinson,2000,p.20).It is not surprising to see the translator’s background playing a part in this regard.More evidence of domesticating tends to appear in works by translators who are native speakers of English.As a matter of fact,there is divergence in the translation strategies used even amongst native English translators.Whilst Sondergard has made an attempt “to follow Pu Songling’s syntax,punctuation,and phrasings faithfully” (Pu,2008,pp.ix),Giles and Minford show marked domestication in their translations,inter alia,by amputating the postscript commentaries so that the Chinese entries intended to pass as history have been transformed into mere stories,as it is compatible with the tradition of English supernatural stories (Cheung,2014,p.115).

Despite divergence in translation strategies proclaimed in the prefaces of the English editions,it is not difficult to notice that their English titles are invariably domesticated; the verbal structure in the Chinese original has unanimously been nominalized in the translated titles.In other words,there is a class shift where the verbal structure in the Chinese title guiding the reader into the world of the strange has shifted to a nominal structure in the English editions.What light does this shed on our understanding of translation as a cross-cultural activity? Over the past twenty years or so,investigations have been carried out into the linguistic patterns typically found in translated texts which are generally known as“universals of translation” or “laws of translation”.For instance,Toury (2012) posits that there is a law of growing standardization and a law of interference (pp.303-315),i.e.a piece of translation is susceptible to simplification in vocabulary and syntax,and to transfer of linguistic features from the source text.2For an overview of other universals,see Chesterman (2004).Is the class shift in question in line with the settled universals or laws? More academic research into the translation of titles seems to be a desideratum,in particular at a point of development in literary and translation studies where paratexts seem to have garnered great interest in recent years as illustrated above.It will be argued in this paper that,being the first point of contact between the book and the reader,a domesticated book title helps secure acceptability of the translation product on the English-speaking market.

There will be four parts to the main body of this article.The first is a descriptive report of the titles ofLiaozhai zhiyiin the English versions,which is followed by a close reading of these titles in the next part,casting light on the nominalization of the Chinese title in the process of translation.For convenience of discussion,the major focus of this paper is book-length translations only,though anthologies may also be covered where necessary and appropriate.The third is an analysis of the nominalization as domestication with reference to the yawning chasm between Chinese and Graeco-Roman world views.An attempt will be made in the last part to explain,with the aid of the Polysystem Theory,the dominance of domestication in the titles of the English editions ofLiaozhai zhiyi.

This piece of research,as a case study,is significant in paving the way for further research into the English translation of titles of other classical Chinesexiaoshuoand hence potential theorization of the translation of titles.

2.Translated titles of the collection in English

The table below shows how the title ofLiaozhai zhiyihas been translated into English over the past century and a half:

3.Discussion of grammatical shift in the translated titles

Prior to an in-depth analysis of the translated titles,we shall look at the Chinese wording.Amongst the four characters in the title,the first two and the last will be dealt with first,considering the greater complexity of the third characterzhi.

The first two characters are semantically straightforward,forliaois the modifier of Pu Songling’s studio (zhai),and their juxtaposition constitutes what is widely held as the name of the author’s studioliaozhai聊斋,although why it was so named and whetherliaozhaias a studio indeed existed were somewhat open to debate (Liu,2008).

The last characteryiis an adjective,literally meaning—etymologically speaking—“being set aside”(Xu,1963,p.59).When one needs to hand something over a (small) table to others,one has to first set it aside for the sake of differentiation.From here is derived the sense of being “unusual” or “extraordinary”.Of course,the adjectiveyihere,functionally refers to things strange,in a similar role to the “the +adjective” structure in the English language.

Zhiis the verb meaning “making records”.Whilst 志 is the character adopted in Pu’s manuscript (Li,1972,p.9),its variant 誌 is seen in some versions,and it is identical to 志 as far as the sense of “making records” is concerned.Much as 志 and 誌 are absolute synonyms in this sense,the author’s preference for the former in the title is of stylistic significance,for the character is often adopted in the titles of imperial official histories,for instance,Sanguo zhi[The Official Record of the Three Kingdoms三国志],andYiwen zhi[A Critical Bibliography艺文志] ofHanshu(History of the Han) (Moss Roberts,“personal communication”,29 June,2018),to name but two.His choice has somewhat placed himself amongst the long line of writers of official histories,lending his work a sense of authority and authenticity.

The verb in a Chinese title has a special role,often indicating the purpose,approach,and/or target readership by placing the work in a wider context.Liu (2006,p.487) argues that the weight that Chinese culture has given to holism and,therefore,consistency has led to the preference for certain characters in nomenclature for the purpose of generic classification.In addition to the names of planets with which Liu illustrates his point,a convenient example is the naming of months in Chinese.Whilst the designations all differ in English,they follow consistently with the pattern of “N+yue月”,whereNis an ordinal number indicating the position of the particular month in a year.

Much as titles do not fall within the ambit of Liu’s discussion,the verb in a traditional Chinese title,a title which stands unaffected by linguistic Europeanization,serves the same purpose—putting the work in a taxonomy.Take the titles of two classical vernacular novels for example.The “yanyi” inSanguo yanyi三国演义 indicates thedevelopmentof the three kingdoms,while “ji” inXiyou ji西游记 means “making a record” of the journey to the West (i.e.India).There is a plethora of other examples,in which some are more familiar than others,for instance,Fusheng liuji浮生六记,Zi buyu子不语,Xuanguai lu玄怪录,Yijian zhi夷坚志,Soushen ji搜神记,Kuoyi zhi括异志,to name but a handful.There are,of course,exceptions where verbs are non-existent such asHonglou meng红楼梦,literally “the dream of the red chamber”,orShanhai jing山海经,literally “the classic of mountains and seas”.Less familiar titles includeLuge nang鹿革囊 by Yu Zhongyun 俞锺云 (Yuan and Hou,1981,p.404) andJinghua shuiyue镜花水月by Loudong Yuyike 娄东羽衣客 (ibid.,p.392).Apparently,they do not seem to be as common as a title carrying a verb,comparatively speaking,as indicated by Yuan and Hou’s (1981) full documentation of classical Chinese tales.

A cursory look at Table 1 gives rise to certain observations.First of all,exceptChinese Ghost and Love Storiesby Rose Quong andSelected Tales of Liaozhaiby Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang,yi,which modifies either “story” or “tale”,has nearly been consistently rendered as strange.Quong did not provide any reason why she adopted a title which deviates from the mainstream rendition.A quick glance at the contents page suggests that there are stories which do not belong to either the ghost stories or love stories,for instance,“Planting a Pear Tree” (the 13th story) and “A Stream of Money” (the 25th story).But this is beyond the scope of our discussion.Nevertheless,it is noteworthy that when Quong refers to the entire collection in her preface,her translation of the title displays much resemblance to those of her counterparts—Strange Stories from the Liao Chai(Pu,1946,p.5).As to the edition of Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang,it is a collection of individual stories published inChinese Literature—a state-run journal—between the 1950s and 1960s (Cheung,2014,p.91).It is worthy of note thatyihas been absent in the title since the first appearance of the translations.It seems plausible speculation that the atheist ideology of the state at the time had a role to play in this regard.

Strictly speaking,“strange” does not seem to do full justice toyi,for whilst “strange” often denotes“unusualness”,“surprise” and “inexplicability” (“strange”,2008a,2008b,2014a),yi,as etymologically explained above,means “being set aside” only.A convenient English equivalent could be “different”.The character is relatively neutral as a phenomenon and can be applicable to both positive and negative contexts.Considering the collocation of “strange”,however,one can see that it tends to appear more often in negative contexts,indicating a negative semantic prosody.Therefore,Collins COBUILD Advanced Learner’s Dictionary,amongst several popular English dictionaries,has rightly highlighted that “strange”refers to something which “makes you feel slightly nervous or afraid” (“strange”,2014b).In other words,the semantic range of “strange” does not appear to be as wide asyi.

Indeed,a number of entries (less than ten) in the collection such asYujiang(于江3/26),1Reference is to the variorum edition of Liaozhai zhiyi of Zhang (1962).The number to the left of the slash refers to the volume (juan 卷) in Zhang’s version and the number to the right is the ordinal,indicating the location of a particular entry in that volume.General Huang(黄将军8/7),andMrs Zhang(张氏妇11/24) do not quite fit neatly to the category of “strange”.Instead,they celebrate the extraordinary wisdom,bravery,or physical power of man.TakeMrs Zhangfor example.Whilst the story is a critique of lasciviousness,it celebrates the eponymous heroine’s wisdom,tact,and sharp wit.Apparently,“strange” as a word for the narrative category does not seem to be themot juste.

Moreover,unlike the noun phrase “ghost story”,where “ghost” is a nounper se,the role ofyi—the strange as a phenomenon to be described—has somewhat been watered down in the expression as “strange stories/tales”,for as a modifier of “story” or “tale”,“strange” is an adjective,carrying an additional shade of meaning:it can be an emotion felt by the reader or the storyteller (Leo T.Chan,personal communication,March 12,2019).This dilution will be more conspicuous in attempts of juxtaposition of the translated titles with those of similar collections in original English,for instance,The Oxford Book of English Ghost Stories(1986),The Penguin Book of Ghost Stories:From Elizabeth Gaskell to Ambrose Bierce(2010),andRoald Dahl’s Book of Ghost Stories(1984).

Of course,“strange” has other less common meanings such as “belonging to some other place or neighbourhood” or “unknown,unfamiliar; not known,met with,or experienced before” (“strange”,n.d.).Taking these less common meanings into consideration,one may agree that not a full equivalent of the Chineseyias “strange” may seem to be.It is adequate as a translation ofyiin the title of the collection,resonating with other works of the supernatural in English literature such as Robert Louis Stevenson’sThe Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde,positioning the readers in the English literary tradition.In other words,the choice of “strange” over its synonyms,or mere “unusualness” is tantamount to a strategy of domestication,because of the connotative meaning of the word “strange”.Nonetheless,this is not the kind of domesticating that this paper is concerned with.The issue in question is nominalization as domestication,which will be further explored below.

The next observation of Table 1 relates to the name of Pu’s study—Liaozhai.Its name in English is far less consistent.For instance,while some translators rendered it intoChinese Studio,Lodge of LeisuresorMake-Do Studio,quite a number of them display a stronger tendency to use a foreignizing romanization such asLiaozhaiorLiaozhai Studio.Except for Sondergard,they are all ethnic Chinese.Despite the variety in the approaches towards naming the author’s study in English,there is no grammatical shift in the translation.

The final observation,which makes the centrepiece of this research,is that none of the translated titles contains a verb.They contain noun phrases and prepositional phrases only.As mentioned,the Chinese verbzhi志/誌 means “to record”.While “record” may also be a noun,the sense“to record” is not reproduced in the translated titles.Instead,it has been merged with and implied in either “stories”or “tales”.Moreover,all titles contain the preposition “from”,indicating the source of the collection.Therefore,by back translation,one would have something likeUnusual Stories from a Chinese Studio(从中国书斋来的奇怪故事).Obviously,semantically speaking,all translated titles show divergence from the original as far as the meaning of “making a record of” is concerned.

4.Discussion

It has just been established that there is consistent nominalization in the translated titles regardless of the differences in the advertised strategies.The nominalized titles enable them—to varying degrees—to pass as an original work in English.In other words,the titles have been domesticated.

According to Shuttleworth and Cowie (1997),domesticating refers to the translation strategy where“a transparent,fluent style is adopted in order to minimize the strangeness of the foreign text for TL readers” (p.44).As far as the role of a translator is concerned,domestication as a strategy indicates,in Venuti’s (2008) words,the invisibility of the translator—his/her “shadowy existence” (p.8).It can be“concerned both with the mode of linguistic and stylistic transfer chosen for foreign texts and with the choice of texts to be translated” (Palumbo,2009,p.38).Venuti (1998b,p.241) illustrated these two aspects of domestication with a series of examples.

There are two points worthy of our attention with regard to domestication.Although Venuti (2008,p.19) makes a distinction between the binary oppositionsdomestication/foreignizationandfluency/resistancy,claiming that the former pair represents ethical attitudes whereas the latter essentially discursive features,the employment of the termdomesticationordomesticatingin this paper refers to the linguistic feature of a translation phenomenon only.

Moreover,it must be noted that domesticating is a relative concept,for as mentioned in the introduction,both strategies are expected to be found in every work of translation.As a matter of fact,a certain degree of foreignizing is discerned in some translated titles.For instance,the adoption of the Romanized studio nameLiaozhai,as the translated title,is a hybrid of both strategies.Nevertheless,the word class of the English title remains a nominal construction.In other words,consistent domesticating is seen in all the translated titles inasmuch as the word class has shifted from a verbal construction in the original to a substantial one in the translation.It is in this sense of domesticating that this paper is concerned with.

There are two questions to be addressed.How does nominalization contribute to the domestication of a Chinese title? A more important question is:Why have the English translations of the titleLiaozhai zhiyibeen unanimously domesticated in this regard?

A straightforward answer to the first question is that there is comparative partiality for nominal structures in English but preference for verbal ones in Chinese.This may well serve as a footnote to the observation by J.Dyer Ball (1847-1919),a 19th century translator based in China’s Hong Kong,that the Chinese language is opposite to English in “almost every action and thought” (as cited in Chan,2001,p.7).

Indeed,whilst the past several centuries have witnessed evolution in the approach to book titling in English—from reference to the names of the central character to the theme or a mystery,or a particular setting or atmosphere,to the modernist symbolic implications in the 20th century (Lodge,1993,pp.193-194),it is still evident that there seems to be a preponderance of the nominal structure in book titles.Amongst the sixteen examples Lodge cited to illustrate centuries of development in titling,thirteen of them use nouns or noun phrases.There is one prepositional phrase and only two contain verbal constructions.Of course,much as Lodge (1993) argues that “at some point in the nineteenth century”titles began to be “resonant literary quotations” (p.194),which may run counter to our argument,for instance,the two examples by Lodge consisting of verbal constructions,it is doubtless that there is a predominance of the nominal structure throughout history.As a matter of fact,nominal dominance in titles is not confined to books,but is also found in other media like film.

When explaining his strategy in translating the poemWang yue望岳,literally “Gazing at the Mountain”,David Hawkes explains in hisA Litter Primer of Tu Futhat

“Gazing at T’ai-shan” is a typically Chinese title for a poem.Our [English] titles are substantival:“Lycidas”,“Home Thoughts from Abroad”,“The Rape of the Lock”.The Chinese are partial to verbal constructions:“Mourning Lycidas”,“Thinking of My Homeland while in a Foreign Country”,“Raping the Lock”,etc.I should feel no compunction in translating this title “On a Distant Prospect of T’ai-shan”,or something of the sort.(Hawkes,1967,p.2)

Hawkes just points out the linguistic patterns and differences between the two languages but does not look into the reason why such a shift is necessary to make the translator “invisible”.

To better understand why nominalization is one of the key tools for domesticating in Chinese-English translation,the role of culture may be called into play.Needless to say,there is an intimate relationship between language and culture.On one hand,language conditions one’s world view according to the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis.Whorf (1956) argues that “the world is presented in a kaleidoscopic flux of impressions which has to be organized by our minds—and this means largely by the linguistic systems in our minds” (p.213).Therefore,whilst we have the binary opposition between “good” and “bad” in general—everything can practically be put under one of the two categories,Bassnett (2013) cites Nida to illustrate the hypothesis that there is a trichotomous classification in a southern Venezuelan language Guaica,where there is a third category “violating taboo” (pp.39-40).

On the other hand,cultures and world views shape the linguistic patterns.For instance,that the apartment number should come before all other information in an English address is the quintessence of individualism of Graeco-Roman culture.In his introduction to the festschrift for D.C.Lau,Ames quotes at length Nietzsche’s explanation of the link between language and “world-interpretation”.It is reproduced here in part to facilitate discussion:

Where there is an affinity of languages,it cannot fail […] that everything is prepared at the outset for a similar development and sequence of philosophical systems; just as the way seems barred against certain other possibilities of world-interpretation.(Ames,1991,p.xx)

To put it simply,Nietzsche argues that the closer the two languages are,the closer the two peoples think.With regard to Chinese and English,Jacques Gernet correctly and concisely remarked that“according to Aristotle,it is normal for all things to be at rest,whereas for the Chinese in contrast universal dynamism is the primary assumption” (as cited in Ames,1991,p.xvi).For this reason,linguistically speaking,there is partiality for the verbal structure in Chinese,whereas in English,the nominal and prepositional structures are more dominant.Liu (2006) has the same observation (p.395),although he takes a linguistic approach to bear out his argument (pp.409-417).

To understand the Chinese preference for verbal constructions in its language,one must be aware of the special and overwhelming reverence for the heavens (tian天) in Chinese culture.It is considered the source of energy giving birth to myriad things on Earth and in this universe.It is by and large correct to say that so far as philosophy is concerned,Confucianism comprises the nucleus of Chinese culture.Thesummum bonumof the Confucian ethos isan安,which means peace,safety and stability (Jao,1954).It is also a significant value which syncretic Chinese culture holds dear.Therefore,there is acute awareness in Chinese culture of the importance of following theWay(aka theTao) of the universe in every single aspect of lives.Such consciousness is also noticeable in the Chinese language.

A dominant feature of the Earth and the universe is that it is in constant motion,or in the words of Leys (1988),a “ceaseless state of flux” (p.15).Therefore,the world view of Chinese culture is one that is dynamic and cyclic,which is encapsulated in theBook of Change(I Ching易经) and is duly reflected in the Chinese language,which has a strong partiality for verbal constructions.It has to be pointed out that our discussion is confined to the Chinese language prior to the 20th century,for it became immensely Europeanized afterward (for detail,see Kubler,1985; Gunn,1991).Chinese titles have also been deeply influenced by the more abstract and individualistic Graeco-Roman culture.

The Chinese special fondness for verbal structures is not least evident in titles—not only original Chinese book titles but also the translated book titles,for instance,those by the twofin de siècleChinese translators Yan Fu (1854-1921) and Lin Shu (1852-1924) (see Ma,1981) as well as dynastic official titles such asZongdu总督 (chief official responsible for monitoring),Buzhengshi布政使 (the official responsible for making policies known and implementing the policies) andZhifu知府 (literally meaning“knowing the prefecture”).A verbal construction is also commonplace for titles of occupations such asZhanggui掌柜 (meaning literally “in charge of the counter”) andSiji司机 (meaning literally “controlling the engine”).

Contrary to the Chinese world view,the Western counterpart is one that is static,contributing to the supremacy of the nominal constructions in the English language.According to Ames (1991),the Western world view,i.e.Graeco-Roman world view,is one of a “dualistic sense of order” and “is grounded in a twoworld reality-appearance distinction” (p.xv).In other words,there are two worlds.The most fundamental one is the “lower” world where one lives and experiences.It is ephemeral and is in constant evolution.Nevertheless,this is not the “real” world,for everything discernible in this world is a duplication of the Ideas in an eternal “upper” world,a “super-nature” world where the Truth lies,where “there is something permanent,perfect,objective,and universal,which,existing independent of the world of change […] an eternal realm of Platonic eidos or ‘ideas’ ” (Ames,1995,p.731).The supremacy of nominal constructions in the English language,not least of abstract nouns,is attributable to the existence of the “permanent,perfect,objective,and universal” upper world.

This dualistic sense of world order can be put down to the strong tradition of rational thought in Graeco-Roman culture.Since the 6th century,rational explanations of nature began to emerge in ancient Greece as a consequence of the impotence of Greek mythology in explaining nature.Since then,“emphasis upon laws of nature as the key to the universe has colored the intellectual traditions of all the peoples influenced by the ancient Greeks” (McNeill,1963,p.214).Rational thought later even found its way beyond explanation of nature to the exploration of society.

More importantly,Graeco-Roman peoples have a keen eye for detail in nature.The attention directed to the form of “the rim of the world” in the Irish writer Donal Ryan’s recent work of fiction is an excellent example:

[…] they stopped at a tiny slipway by a stunted quay and a gull bent itself to the breeze and screamed as Farouk and his wife and his daughter looked across a desert of water to the curve of the rim of the world.(Ryan,2018,p.21)

Certainly,“the rim of the world” is a concept which exists in both Chinese and English.But that the observation and hence the description in the novel make reference to even its shape is highly likely to be unique in English.For one thing,this is a consequence of the strong tradition of science as a result of the aforementioned enthusiasm for explanation of natural phenomena in the West.This science tradition,with observation at its heart,was further strengthened by the development of the Scientific Revolution in the 16th and 17th centuries,and the Enlightenment Movement in the 18th century.Christianity also contributes to the predominance of nominal constructions in English,for this (perfect) world,according to Scripture,was created by God.This being the case,Western artists are,on the whole,more attentive to minute details in their artworks—representation of the perfect world—when compared with their Chinese counterparts.As far as the English language is concerned,a keen eye for detail in Graeco-Roman culture leads to the supremacy of prepositions,contributing to the precision and objectivity of the language.Since a preposition is “[a]n indeclinable word or particle governing (and usually preceding) a noun,pronoun,etc.,and expressing a relation between it and another word” (“preposition”,n.d.),it is natural to see the high frequency of the substantial and prepositional structures in English.In short,it is the special place of rationality—and hence the keen observation of the world and the dual sense of world order—which contributes to the prevalence of nominal constructions in the English language.

5.Position and translation strategy

Having established that the unanimous replacement of Chinese verbal structures by nominal constructions in English and ofzhi(to record) by either “stories” or “tales” in the translated titles are examples of domestication underpinned by two different world views,we shall attempt to answer our second question:Why are all translated titles in the English editions domesticated,regardless of the translation strategy adopted?

There could be several explanations.One obvious reason,I gather,is that the huge success of Giles’s translation—commercially and academically—has set a precedent for later translators to follow.Indeed,Minford (2006) confesses that he is a great fan of Giles and he has adopted “the occasional felicitous phrase of his” in his own translation when he considered Giles had gone one better (p.xxxiii).Although Pym(1998) argues that “retranslations sharing virtually the same […] generation must respond to something else” (p.82) whereas translations temporally wide apart do not show much “disturbing influence” (p.82),Giles’s rendition,albeit produced 140 years ago,is certainly an example of “active retranslation” according to Pym’s categorization,exerting active influence on its successors.

Nevertheless,the consistent use of domestication in nearly one and a half centuries of translated titles seems to be less by accident than on purpose.Translation is a purposeful activity,as the Skopos school argues and Christiane Nord’s (1997) well-received book suggests.For instance,in the foreword toStrange Tales of Liaozhai,the translators remarks that they “have made every endeavor to be faithful to the original and tried [their] best to capture the spirit of this great work” (Pu,1982,p.ii).In this regard,“the concluding comment made by this Recorder of Marvels […] has been translated without omission” (p.ii).Considering that sales volumes,at least in part,contribute to the survival of a publisher,I argue that a title—being the first point of contact between the book and the reader—has a role to play in this regard.To domesticate a title,as argued in the foregoing section,is to adopt a nominal structure in the title in order to reduce the distance between the translation and its readers through engaging the latter in the English literary tradition.In other words,a domesticated title has a part to play in the acceptability of the translation.

I might be accused of platitudinousness in arguing that the acceptability of the translation is a function of the degree of domestication.In other words,foreignizing and hence foreignness means distance and rejection.Nevertheless,this may not be entirely true in the history of the English language.For one thing,norms of translation do shift historically (Robinson,2000).For another thing,for a considerable length of time in the history of the English language—perhaps from the fall of the Roman Empire all the way down to the late 17th century,a Latin title (a “foreign” language to the English readership) would be more likely to appeal to readers in England.Some notable examples include Sir Thomas More’sUtopiaand Isaac Newton’sPhilosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica.With reference to the asymmetry between the Chinese and English languages which will be further elaborated shortly and to the historical period in question (from the first book-length translation ofLiaozhai zhiyiin 1880 to present),it is undoubtedly true that a domesticated title contributes to the acceptability of an English edition.

To further illustrate my point,I shall make reference to the Polysystem Theory,for it shows the dynamism in the choice of strategy in translation,illustrating how a strategy is conditioned by the position of translations in the target literary system.According to the Polysystem Theory,literature is made sense of in terms of systems,i.e.“networks of relations that can be hypothesized for a certain set of assumed observables” (Even-Zohar,2010,p.40).A polysystem is “a multiple system,a system of various systems which intersect with each other and partly overlap,using concurrently different options,yet functioning as one structured whole,whose members are interdependent” (p.42).Translated literatureper seis a system,which is an “integral” and “active” part within a wider context of literary polysystem (Even-Zohar,1990,p.46).

This theory throws light on the choice of the source text for translation,the “specific norms,behaviors,and policies” (ibid.,p.46) of translation upon the assumption of a rational preference for the centre position in the polysystem,for “polysystem constraints are interdependent with the procedures of selection,manipulation,amplification,removal,etc.,taking place in actual products pertaining to the polysystem” (Even-Zohar,2010,p.45).

According to Even-Zohar,a polysystem broadly consists of two repertoires—central (primary)and peripheral (secondary) (ibid.,p.45).As far as translated literature is concerned,he hypothesises that the central position of translated literature represents innovation whilst the peripheral position of translation suggests conservation.In other words,the peripheral position that translations occupy compels conformity to the literary norms of the target language and culture,whereas the central position taken up by translated literature induces changes to literary conventions in the target language and culture,and the creation of new ones.With regard to translation strategy,domesticating is normally more frequently seen when translated literature assumes a peripheral position whilst foreignizing dominates when it is not.Translation is more likely to assume a central position when a literature is young,“peripheral” or “weak”,or when there are turning points,crises,or literary vacuums in literature (Even-Zohar,1990,p.47).

While Chinese translations were situated at a central position of the Chinese literary polysystem in the early 20th century,leading to the introduction of Western thought and novel literary genres and techniques into China as well as,for better or for worse,the Europeanization of the Chinese language,it is the original works of literature in English which have remained in the primary repertoire of the English literary polysystem.

As far as translations are concerned,they generally find themselves in the periphery of the polysystem of English literature.Even-Zohar rightly points out that Anglo-American literature in France,comparable to French translated literature,assumes “an extremely peripheral position” (ibid.,p.50).His generalization also holds true with respect to the translation of Chinese literature into English.

Of course,there is little doubt that the centrality of original works of English literature in relation to translated works from Chinese in the polysystem of English literature was attributable to the hierarchy of international power.In sociolinguistic parlance,English was the high language whereas Chinese was the low language in this pair.It is worthy of mention,however,that this remains so even after World War II,a power reshuffle for the majority,if not all,of the countries around the globe,for “translation patterns since World War II indicate the overwhelming domination of English-language cultures” (Venuti,1998a,p.160).Derrida notes that “the English language is today hegemonic[…] not simply replacing all the languages on earth,but becoming the second universal language.Everyone has to speak his own language plus English” (as cited in Davis,2014,p.6).Therefore,the position of translations into English remains more or less the same in the periphery vis-à-vis works of literature in original English in the polysystem of English literature.Chang (2017) notes that “the efforts [on the part of China] to disseminate Chinese literature have had little impact on the West so far” (p.644).In response to the rise of China and hence the efforts at increasing cultural exchange,Douglas Robinson opines that what interests people of the West is the “economic power” of China rather than translations of Chinese literature and her “cultural products”(Qin,2013,p.33).

Perhaps as a consequence of this situation,a transformation from single patronage to joint patronage is seen in the English translation of Chinese literature (Bai,2017).In other words,instead of one single Chinese translator,there is cooperation between Chinese and English scholars and translators.According to him,the products under the new collaboration are a huge success,which in turn,reveals the peripheral position of translated literature in the polysystem of English literature.

In short,it is because of the asymmetry of power between the Chinese and English languages that a domesticated title has been chosen in order to maximize the acceptability of an English edition of theLiaozhai zhiyion the English market,regardless of the translation adopted or the socio-economic background against which a translation is produced.

6.Concluding remarks

With reference to commercial considerations,it has been established in this paper that a domesticated title has a role to play in the success of an English translation on the English-speaking market in the hope to make sense of the strangely unanimous domestication in the translated titles of the English versions ofLiaozhai zhiyi.Apparently,in the long history of the English translation ofLiaozhai zhiyi,some English versions are more successful than others.For instance,Giles’s translation,which was first published in the 19th century,is still in print.A domesticated title is not a guarantee of success but a hope for success only.

Whilst we have had a substantial discussion on the issue of title translation,we have not shed any light on the “translator-ship”.By no means does this paper suggest that the translated titles are simply the translators’ decision.According to Lefevere (1992),a work of translation is not only the product of the translator,but also of patronage,which refers to “something like the powers (persons,institutions) that can further or hinder the reading,writing,and rewriting of literature” (p.12).Publishers are considered as one of the patrons,having a part to play in the design of the title and others.Therefore,it is not uncommon to learn of the intervention of the publisher in the choice of the title (Lodge,1993,pp.195-196).

This paper represents only a preliminary attempt to explore the translation of titles.Do the translated titles of individual entries display a similar pattern? Whilst Roberts (1979) has rendered the entryXi Fangping(席方平10/398) asUnderworld Justice,highlighting its subject matter,Sondergard has merely adopted the RomanizationXi Fangping.It seems that translated titles of individual stories display greater complexities than those of the collection.Moreover,two versions of a title were often given in earlier translations.For instance,Dongsheng(董生2/44) was rendered asMr.Tungor,Virtue Rewardedin Giles’s edition.What light do these patterns cast on the translation of titles? Do the same patterns occur in the translated titles of other classical Chinese tales? Does it occur in other media such as the translation of film titles? In investigating Sir Charles’s death inThe Hound of the Baskervilles,Sherlock Holmes reminds Dr Watson to “report facts in the fullest possible manner” and it is the business of Holmes himself “to do the theorizing” (Doyle,1902,p.51).My attempt in this paper is to follow in the footsteps of Watson and paint a picture of the translations of the collection title,Liaozhai zhiyi,in the hope that I can set the stage for theorizing the translation of book titles in the future.

杂志排行

翻译界的其它文章

- Purpose-driven Texts and Paratexts:A Comparative Study of Three Retranslations of Xixiang ji

- The Re-narrated Chinese Myth:Comparison of Three Abridgments of Journey to the West on Paratextual Analysis1

- Transference of Things Remote:Constraints and Creativity in the English Translations of Jin Ping Mei

- Classical Chinese Literature in Translation:Texts,Paratexts and Contexts

- Images of Chinese Women in the Hands of Translators:A Case Study of the English Translations of Pu Songling’s Liaozhai zhi yi

- Paratexts in the Partial English Translations of Sanguo yanyi