Associations between obesity and metabolic health with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in elderly Chinese

2020-07-07LiMingWuHuiHeGngChenYuKungBingYiLinXinHuChenShuSenZheng

Li-Ming Wu , Hui He , Gng Chen , Yu Kung , Bing-Yi Lin , Xin-Hu Chen ,Shu-Sen Zheng , ∗

a Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310 0 03, China

b Department of Internal Medicine, Shaoxing Keqiao Women and Children’s Hospital, Shaoxing 312030, China

c Medical Physics Program, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV 89121, USA

Keywords:Fatty liver disease Obesity Metabolic health Elderly

A B S T R A C T Background: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is closely associated with obesity. However, this association could be influenced by the coexisting metabolic abnormalities. This study aimed to investigate the role of obesity and metabolic abnormalities in NAFLD among elderly Chinese.Methods: A cross-sectional study was performed among elderly residents who took their annual health checkups during 2016 in Keqiao District, Shaoxing, China.Results: A total of 3359 elderly adults were retrospectively included in this study. The overall prevalence of NAFLD was 28.7%. The prevalence of NAFLD were 7.14%, 27.92%, 34.80%, and 61.02% in participants with metabolically healthy normal weight (MHNW), metabolically abnormal normal weight (MANW), metabolically healthy obese (MHO), and metabolically abnormal obese (MAO), respectively. NAFLD patients in MHO group had more unfavorable metabolic profiles than those in MHNW group. Logistic regression analysis showed that sex, body mass index (BMI), fasting blood glucose, and serum uric acid were the risk factors of NAFLD.Conclusions: Both obesity and metabolic health were significantly associated with NAFLD in elderly Chinese. Screening for obesity and other metabolic abnormalities should be routinely performed for early risk stratification of NAFLD.

Introduction

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is characterized by hepatic steatosis in the absence of a history of excessive alcohol consumption or other known liver disease [1] . It affects approximately 15% −30% of the adults worldwide and 29.2% adults in China [2-4] . The spectrum of NAFLD ranges from simple steatosis to steatohepatitis, and cirrhosis [5] . NAFLD is also associated with hepatocellular carcinoma [6 , 7] . Moreover, NAFLD independently and significantly increases the risk of dyslipidemia, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and thus, increases the risk of cardiovascular diseases [8 , 9] . Due to its high prevalence and significant health impacts, NAFLD has been considered a global public health problem.

Obesity is not only a risk factor of NAFLD, but also correlated with a potential progress to end-stage of liver disease [10] .Meanwhile, obesity contributes significantly to the development of metabolic syndrome [11] . It is uncertain whether obesity is the solely risk factor for NAFLD, or is also mediated by the coexisting metabolic abnormalities [12] .

The analyses of individuals who are metabolically abnormal but normal weight (MANW) and metabolically healthy but obese (MHO) provide insights into the association among obesity,metabolic status, and NAFLD. Although the MANW individuals have a normal body mass index (BMI), they usually display several metabolic abnormalities such as atherogenic lipid profiles, decreased insulin sensitivity, and impaired glucose tolerance [13 , 14] .On the contrary, MHO individuals are phenotypically obese but exhibit normal insulin sensitivity and have a lower inflammation state than metabolically abnormal obese (MAO) individuals [15 , 16] .

MANW and MHO individuals, with metabolic abnormalities only or obese only respectively, represent two specific risk phenotypes of NAFLD. A previous study reported that MHO individuals had lower serum liver enzymes compared with at-risk controls [17] . Another large cross-sectional study reported that both MANW and MHO individuals have higher prevalence of fatty liver than metabolically healthy normal weight (MHNW) individuals, but alcoholic fatty liver was not excluded in the analysis [18] .To the best of our knowledge, the separate and combined associations of obesity and metabolic health with NAFLD among elderly adults have not been investigated. Solving this issue would provide valuable information for disease prevention and management.

This cross-sectional study was to evaluate the separate and combined associations of obesity and metabolic health with NAFLD among elderly Chinese.

Patients and methods

Studypopulation

A cross-sectional study was conducted to investigate the separate and combined associations of obesity and metabolic health with NAFLD among elderly Chinese. The study participants were selected from elderly (age ≥60 years) residents in Keqiao District (Shaoxing, China) who took their annual health checkups during 2016. We excluded participants for the following reasons:(i) uncompleted anthropometric data; (ii) alcohol consumption>140 g/week for men and 70 g/week for women; (iii) had a history of viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis or other forms of chronic liver disease; (iv) took steatogenic drugs based on their self-reported medical history; (v) BMI<18.50 kg/m2. A total of 3359 eligible participants were included into the final analysis. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Clinicalevaluations

Clinical evaluations were conducted according to standard procedures. Self-reported medical history, medication use, alcohol consumption, and smoking habits were recorded by trained staffs.Height and body weight were measured without shoes and in light clothing after overnight fasting. BMI was calculated as body weight(kg) divided by height (m) squared. Blood pressure was measured with the participants in a sitting position. Waist circumference was measured midway between the lowest rib and the iliac crest using a flexible anthropometric tape.

Blood samples were collected after an overnight fasting and were used for the laboratory measurements without freezing.Serum biochemical variables were measured by a Hitachi 7180 autoanalyzer (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) using standard methods. Hematological variables were analyzed by a MINDRAY Hematology Analyzer BC5180 (Shenzhen, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Definitions

NAFLD was diagnosed by abdominal ultrasonography, after exclusion of alcohol consumption, viral, or other chronic liver disease [19] . The ultrasonography examinations were carried out by experienced ultrasonographers who were blinded to study groups,using a GE LOGIQ S6 sonography machine with a 3.5-MHz probe.

We defined obesity (overweight) as a BMI ≥25.0 kg/m2, and normal weight (non-obese) as a BMI of 18.5 to 25.0 kg/m2[20] .We defined metabolically abnormal as participants who met more than two abnormality of the following metabolic syndrome criteria recommended by new International Diabetes Federation (IDF) [21] :(i) central obesity, defined as waist circumference ≥90 cm for Chinese man and ≥80 cm for Chinese woman; (ii) hypertriglyceridemia, defined as triglycerides ≥1.70 mmol/L, or specific treatment for this lipid abnormality; (iii) low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol concentration, defined as HDL cholesterol<1.03 mmol/L in male and<1.29 mmol/L in female; (iv) elevated blood pressure, defined as systolic blood pressure ≥130 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥85 mmHg, or treatment of previously diagnosed hypertension; and (v) hyperglycemia, defined as fasting blood glucose ≥5.60 mmol/L, or previously diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Participants who had two or less abnormality described above were defined as metabolically healthy. All participants were classified into four metabolically defined body size phenotypes:MHNW, MANW, MHO, and MAO.

Statisticalanalysis

All the statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS software,version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables are presented as mean ±standard deviation (SD), and compared by Student’st-test, or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc Tukey’s test. Categorical variables are presented as number(percentage) of the participants, and compared by Chi-square test.Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the risk factors for NAFLD in the whole study population as well as in participants with different metabolically defined body size phenotypes. A two-tailedPvalue less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinicalcharacteristicsofthestudypopulation

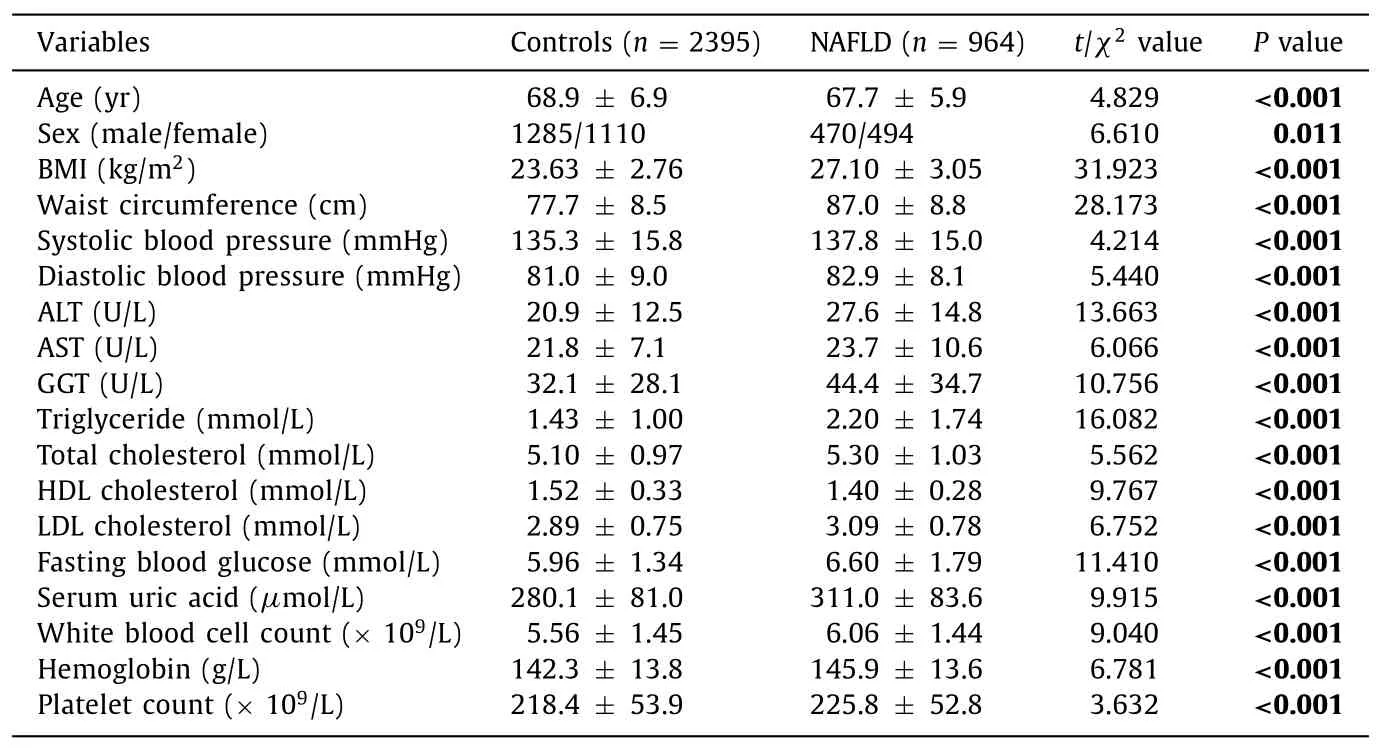

We enrolled 3359 elderly participants (1755 men and 1604 women) with mean age of 68.6 ±6.7 years in this study. A total of 964 (28.7%) NAFLD patients were identified based on ultrasonography examination. We also detected 11 cases of liver cirrhosis by ultrasonography among the 3359 participants. These 11 cases were considered cryptogenic cirrhosis, and some of these cases might be NASH-related cirrhosis. The clinical characteristics of participants were compared based on their NAFLD status ( Table 1 ). NAFLD patients had higher BMI, waist circumference, systolic and diastolic blood pressure than those without NAFLD. NAFLD patients also had higher serum levels of liver enzymes including alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and gammaglutamyltransferase (GGT). Glucose, and uric acid, and unfavorable serum lipid profiles including triglyceride, total cholesterol, HDL and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol were also more frequently abnormal than the control group. These results showed that NAFLD patients had unfavorable metabolic profiles.

Associationofbodysizewithprevalenceandclinicalcharacteristics ofNAFLD

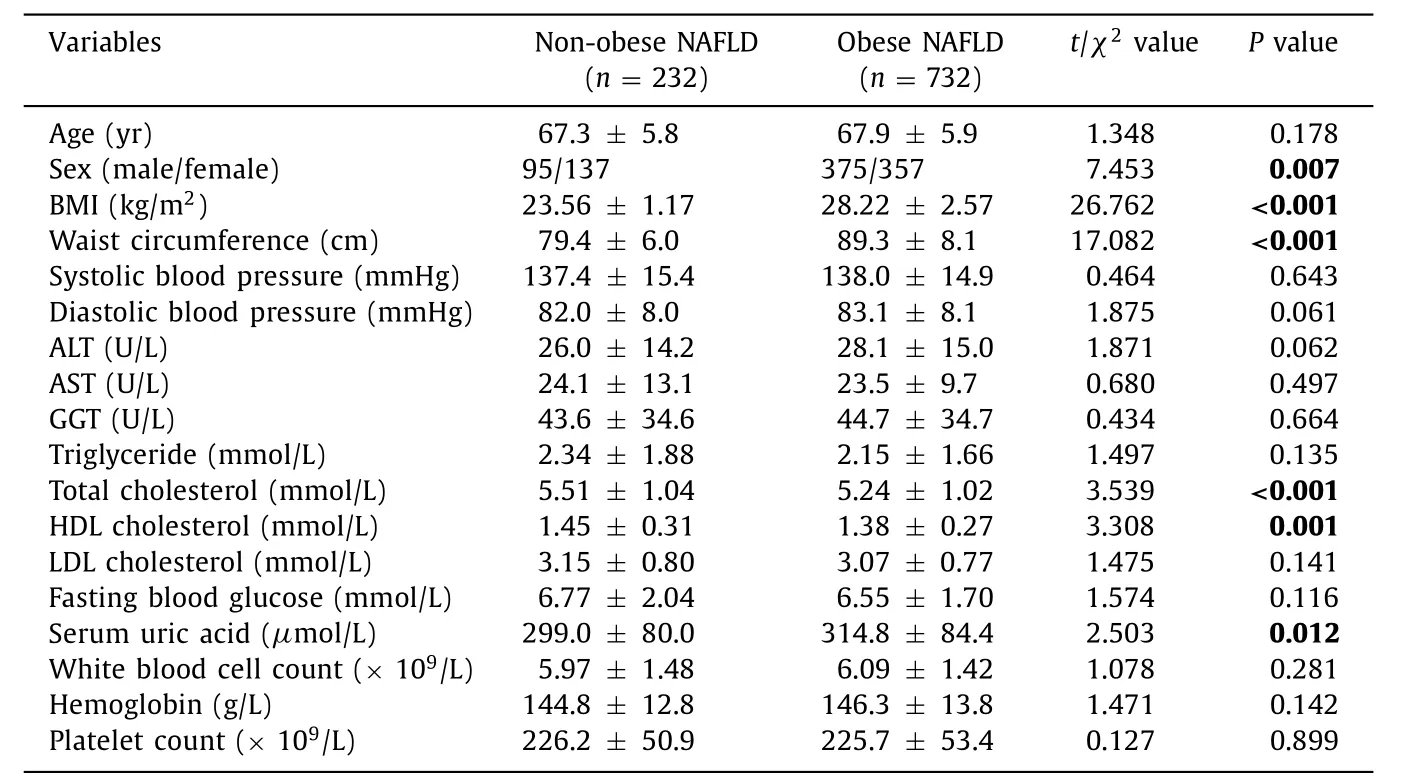

Of 3359 participants, 1454 were obese and 1905 were nonobese. The prevalence of NAFLD was 50.34%, and 12.18% among obese and non-obese participants, respectively. The clinical characteristics of NAFLD were compared based on body size ( Table 2 ).Obese NAFLD patients had lower HDL cholesterol and higher uric acid level than non-obese NAFLD patients. Age, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, serum levels of liver enzymes, triglyceride,LDL cholesterol, and glucose were comparable between obese and non-obese NAFLD patients. These findings suggest that both nonobese and obese NAFLD patients shared several clinical and laboratory characteristics, although NAFLD was more prevalent among obese participants.

Table 1 Clinical characteristics of participants with different NAFLD status.

Table 2 Clinical characteristics of NAFLD patients with different body size.

Associationsofmetabolicallydefinedbodysizephenotypeswith prevalenceandclinicalcharacteristicsofNAFLD

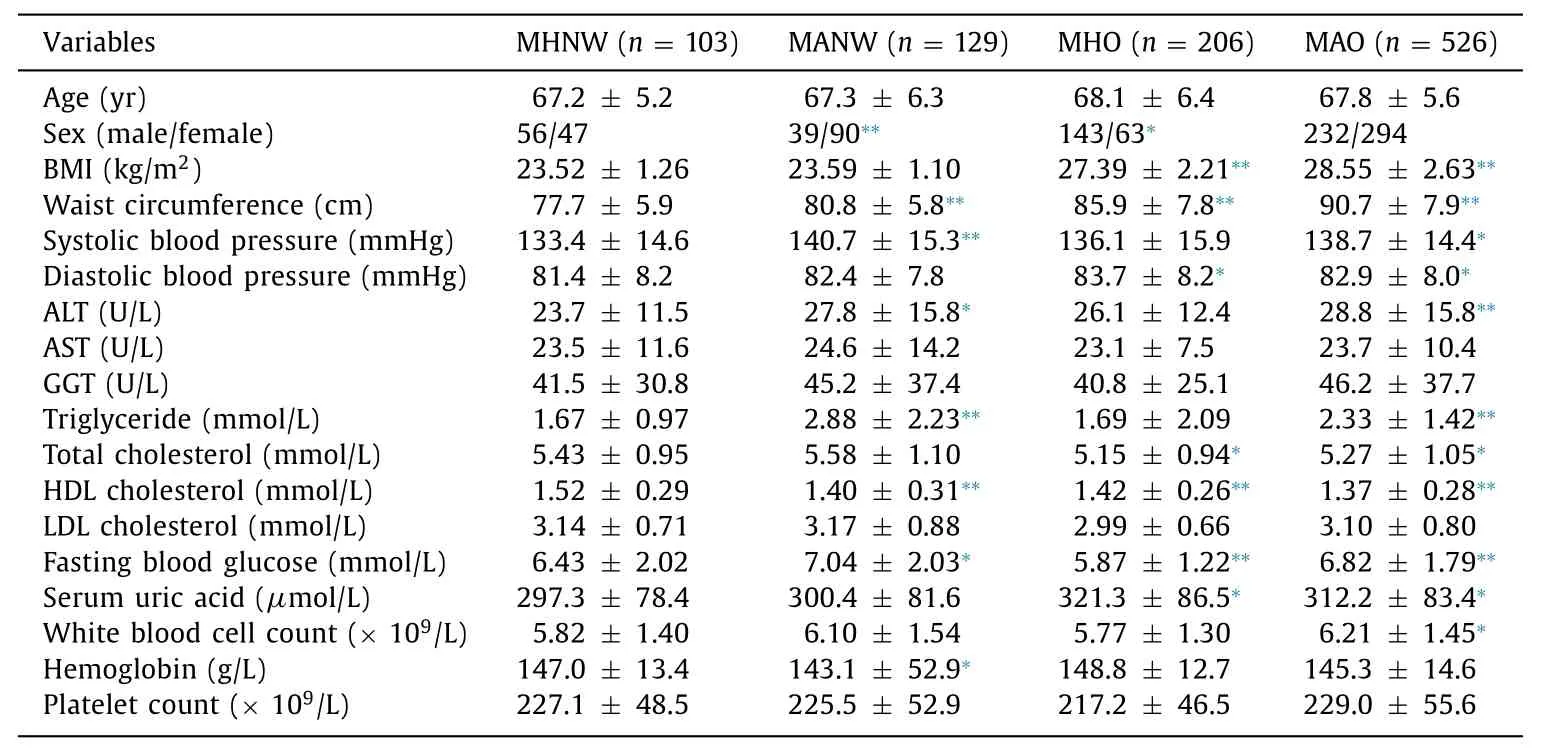

We further classified all participants into four groups according to their metabolically defined body size phenotypes, 1443 (42.96%)were MHNW, 462 (13.75%) were MANW, 592 (17.62%) were MHO,and 862 (25.66%) were MAO. The prevalence of NAFLD were 7.14%,27.92%, 34.80%, and 61.02% in MHNW, MANW, MHO, and MAO,respectively. The clinical characteristics of NAFLD patients according to metabolically defined body size phenotypes were shown in Table 3 .

NAFLD patients with MHNW and MANW body size phenotypes had comparable BMI. However, patients with MANW phenotype had higher waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, ALT,triglyceride, fasting blood glucose, and lower HDL cholesterol levels than those with MHNW phenotype. Compared to patients with MHNW phenotype, those with MHO phenotype had significantly higher BMI, waist circumference, diastolic blood pressure, uric acid,and lower HDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, and fasting blood glucose levels. This finding suggests that patients with MHO phenotype tend to have more unfavorable metabolic profiles than those with MHNW phenotype, although they were both metabolically healthy.

Associationsofmetabolicallydefinedbodysizephenotypeswithrisk factorsofNAFLD

We performed a binary logistic regression using NAFLD as independent variable in the whole study population, and found that age, sex, obesity, metabolic syndrome, ALT, serum uric acid,and hemoglobin were significantly associated with risk factors of NAFLD in the whole study population ( Table 4 ).

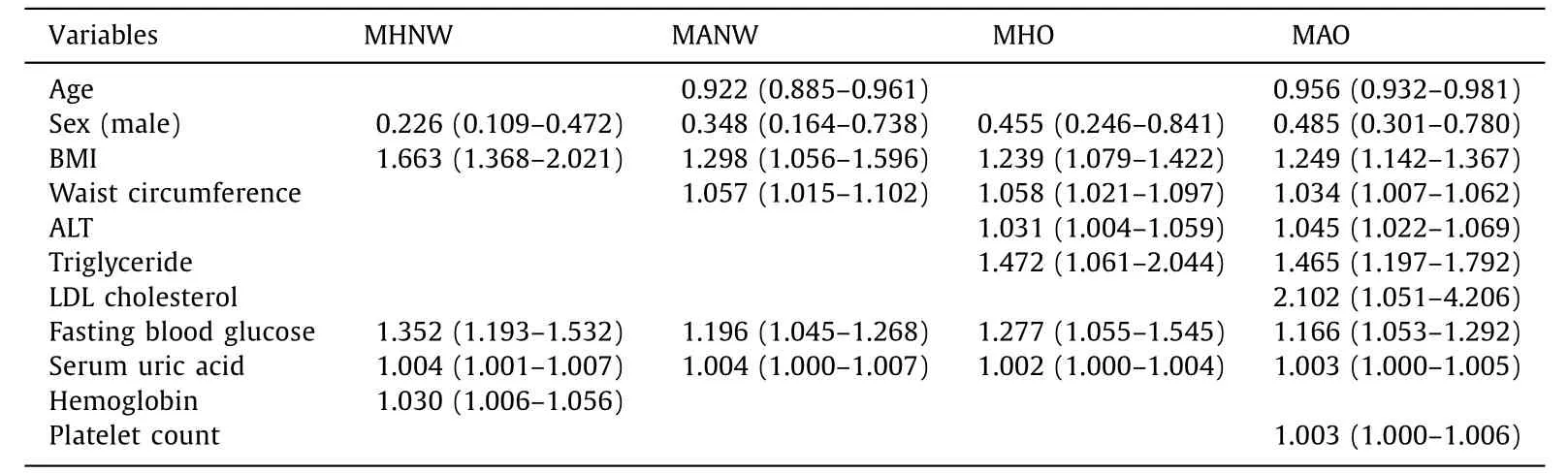

Risk factors of NAFLD in participants with different metabolically defined body size phenotypes were also analyzed by multivariate logistic regression analysis. The risk factors of NAFLD varies among different phenotypes ( Table 5 ). A noticeable finding was that sex, BMI, fasting blood glucose, and serum uric acid were always associated with risk factors of NAFLD in participants withdifferent metabolically defined body size phenotypes. This finding suggests that more attentions should be paid to these four factors for early risk stratification of NAFLD.

Table 3 Clinical characteristics of NAFLD patients with different metabolically defined body size phenotypes.

Table 4 Logistic regression analysis of risk factors for NAFLD in the whole study population.

Table 5 Logistic regression analysis of risk factors for NAFLD in participants with different metabolically defined body size phenotypes.

Discussion

In this study, we examined separate and combined associations of obesity and metabolic health with NAFLD among elderly Chinese. Our results showed that both obese and non-obese NAFLD patients shared several clinical and laboratory characteristics, although NAFLD was more prevalent among obese participants. Our results also showed that participants who were obese and/or with metabolically abnormalities had elevated prevalence of NAFLD as compared to metabolically healthy normal weight participants. Patients with MHO phenotype had more unfavorable metabolic profiles than those with MHNW phenotype. Logistic regression analysis showed that sex, BMI, fasting blood glucose, and serum uric acid were common risk factors of NAFLD in participants with different metabolically defined body size phenotypes. These results may have significant clinical implications.

MANW and MHO represent two specific metabolically defined body size phenotypes. MANW, also known as metabolically obese,refers to normal weight individuals who have several metabolic abnormalities commonly found in obese persons [13] . On the other hand, MHO refers to obese individuals who have a favorable metabolic profile such as normal serum lipids, glucose, and blood pressure [15] . MANW individuals tend to have more abdominal fat distribution, worsen inflammatory status, and higher dyslipidemia prevalence than MHNW individuals [14 , 22] , while MHO individuals have reduced inflammation and less visceral fat compared with their MAO counterparts [15 , 23] . In this study, we applied the updated IDF criteria to define metabolic health, and found that 42.96%, 13.75%, 17.62%, and 25.66% were MHNW, MANW, MHO,and MAO, respectively. Therefore, MANW and MHO account for more than 30% of the study population.

The role of MANW and MHO as risk factors for metabolic diseases with significant public health impacts has been extensively investigated during recent years. Despite the fact that MANW individuals have a normal BMI, they usually have an increased risk for developing type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases [24 , 25] ,whereas although MHO individuals are usually obese, they may not have the increased risks [26-29] .

NAFLD is a high prevalent metabolic disease with significant clinical implication. In this study, we found that the prevalence of NAFLD were significantly higher in MANW, MHO, and MAO individuals than that in MHNW individuals. Patients with MHO phenotype had more unfavorable metabolic profiles than patients with MHNW phenotype, although they were both metabolically healthy.These results suggest that MANW and MHO individuals are not as healthy as MHNW individuals. And a significant association of obesity and metabolic health with NAFLD may exist.

Given the retrospective nature of this study, several limitations are noted. Firstly, the diagnosis of NAFLD was by ultrasonography,which may miss some incident cases with mild hepatic steatosis.Nevertheless, because of its low cost, safety, and availability, ultrasonography is widely used for NAFLD screening with acceptable diagnostic accuracy [30] . Secondly, data on insulin resistance were not available in this study. As a result, we defined metabolic health based on the updated IDF criteria, instead of insulin sensitivity measurements. Despite this fact, we believe that the results would not be likely to be significantly influenced using different definition criteria, since previous prospective studies reported consistent results using both criteria [31 , 32] . Thirdly, information on dietary and physical activity was not recorded in this study. It would be interesting to analyze whether dietary and/or physical activity influences the risk of NAFLD in MANW and metabolically healthy individuals.

In conclusion, our results show that both obesity and metabolic health were significantly associated with NAFLD in elderly Chinese.Therefore, screening for obesity and other metabolic abnormalities should be routinely performed for early risk stratification of NAFLD.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Cheng-Fu Xu (Department of Gastroenterology, the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine) for his valuable comments on the manuscript.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Li-Ming Wu:Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.Hui He:Formal analysis, Investigation.Gang Chen:Data curation,Investigation.Yu Kuang:Validation, Writing - review & editing.Bing-Yi Lin:Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing - original draft.Xin-Hua Chen:Project administration, Writing - review& editing.Shu-Sen Zheng:Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing- review & editing.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Key Research Development Program of Zhejiang Province (2018C03018), and Major Science and Technology Projects of Medicine and Health in Zhejiang Province (WKJ-ZJ-1923, 2020383364), National Key R and D Program of China ( 2017YFCO114102 ).

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine.

Competing interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for a patient with chylothorax in cryptogenic/metabolic cirrhosis

- Differential methylation landscape of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and its precancerous lesions

- Hepatobiliary&Pancreatic Diseases International

- MicroRNAs and long non-coding RNAs in liver surgery: Diagnostic and therapeutic merits

- Alpha-fetoprotein and 18 F-FDG standard uptake value predict tumor recurrence after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombosis: Preliminary experience

- Translationally controlled tumor protein exerts a proinflammatory role in acute rejection after liver transplantation