Clinicopathological features and prognosis of surgical resected cases of biliary cancer with pancreaticobiliary maljunction

2020-03-03TsuksTkyshikiHideyukiYoshitomiKtsunoriFurukwStoshiKubokiMsruMiyzkiMsyukiOhtsuk

Tsuks Tkyshiki , Hideyuki Yoshitomi , Ktsunori Furukw , Stoshi Kuboki , Msru Miyzki , b , Msyuki Ohtsuk , *

a Department of General Surgery, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, 1-8-1 Inohana, Chuo-ku, Chiba 260-0856, Japan

b Department of Gastroenterological Surgery, Mita Hospital, International University of Health and Welfare, 1-4-3 Mita, Minato-ku, Tokyo 108-8329, Japan

To the Editor:

Pancreaticobiliary maljunction (PBM) is a congenital anomaly in which the pancreatic and bile ducts join anatomically outside of the duodenal wall away from the Oddi’s sphincter. This condition causes the reflux of pancreatic juice into the bile duct under high pressure, resulting in various pathologic changes. The features of PBM patients are common bile duct dilatation, long common chan- nel, and high amylase levels in bile juice. Among them, one of the most significant problems is the development of biliary cancer, in- cluding extrahepatic bile duct and gallbladder cancers [1] . A na- tionwide survey in Japan reported biliary cancer in 21.6% of adult patients with PBM concomitant with congenital biliary dilatation, 32.1% and 62.3% extrahepatic bile duct and gallbladder cancers, re- spectively [2] . The problems of PBM were previously considered to be relatively specific in Asia because the number of Asian patients with PBM is greater than that of Western patients. However, a re- cent French multicenter study reported that the therapeutic impli- cations and guidelines of the Japanese PBM study group were ap- plicable to the European population [3] , suggesting that the high risk of biliary cancer in patients with PBM is an important issue in not only Asia but also Western countries.

Biliary cancer associated with PBM is pathologically and ge- netically different from that without PBM. Biliary cancer asso- ciated with PBM may develop through a hyperplasia-dysplasia- carcinoma sequence, while biliary cancer without PBM is an adenoma-carcinoma sequence or de-novo carcinogenesis. In addi- tion, genetically, K-ras and/or p53 mutations have been observed in noncancerous bile duct and gallbladder epithelia of patients with PBM [4] . Based on these findings, the clinical outcomes of sur- gically resected cases of biliary cancer with PBM may also differ from those of patients without PBM. However, the clinicopatholog- ical features and prognosis after surgical resection in biliary cancer patients with PBM are rarely reported. This study assessed the clin- icopathological features and prognosis of surgically resected cases of biliary cancer with PBM and compared them with those without PBM.

The medical records of all patients with biliary cancer undergo- ing surgical resection between January 2001 and December 2017 at Chiba University Hospital were reviewed in order to retrieve patient characteristics, pathologic findings and survival rates. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional re- view board.

Multi-detector row computed tomography, endoscopic retro- grade cholangiopancreatography, and magnetic resonance imaging were the main diagnostic modalities for biliary cancer. Patients with more than two lesions in the common bile duct and/or gallbladder detected simultaneously by these modalities that were finally postoperatively diagnosed as carcinomas were defined as having multiple biliary cancers. The diagnosis of PBM was determined based on the criteria of the Japanese study group for PBM [5] .

The selection of surgical procedure for biliary cancer depended on the tumor location and the extent of tumor spread in individ- ual patients. Major hepatectomy such as hemihepatectomy and tri- sectionectomy, with caudate lobectomy and extrahepatic bile duct resection, was performed in patients with perihilar cholangiocarci- noma, while pancreaticoduodenectomy was performed in patients with distal cholangiocarcinoma. In patients with gallbladder can- cer, simple cholecystectomy or cholecystectomy with resection of segment VIa + V and extrahepatic bile duct resection were generally performed if R0 resection could be achieved; in more advanced cases with gallbladder cancer, major hepatectomy with extrahep- atic bile duct resection or pancreaticoduodenectomy was selected as the surgical procedure. Regional lymph nodes including those in the hepatoduodenal ligament, on the posterior surface of the head of the pancreas, and along the common hepatic artery, were routinely dissected. In cases requiring major hepatectomy, preop- erative portal vein embolization was performed when the feature remnant liver volume was estimated to be less than 40% of the to- tal liver volume. All resected specimens were preserved for patho- logic examination and categorized according to the pathological tu- mor node metastasis (pTNM) classification based on the seventh edition of the International Union Against Cancer (UICC) staging system. All patients were followed up in out-patient clinics ev- ery 3-6 months. Adjuvant gemcitabine-based chemotherapy was administered according to the institutional guidelines. The failure event for survival was defined as death from any cause. Survival time was measured from the date of surgery to the date of death or last follow-up evaluation.

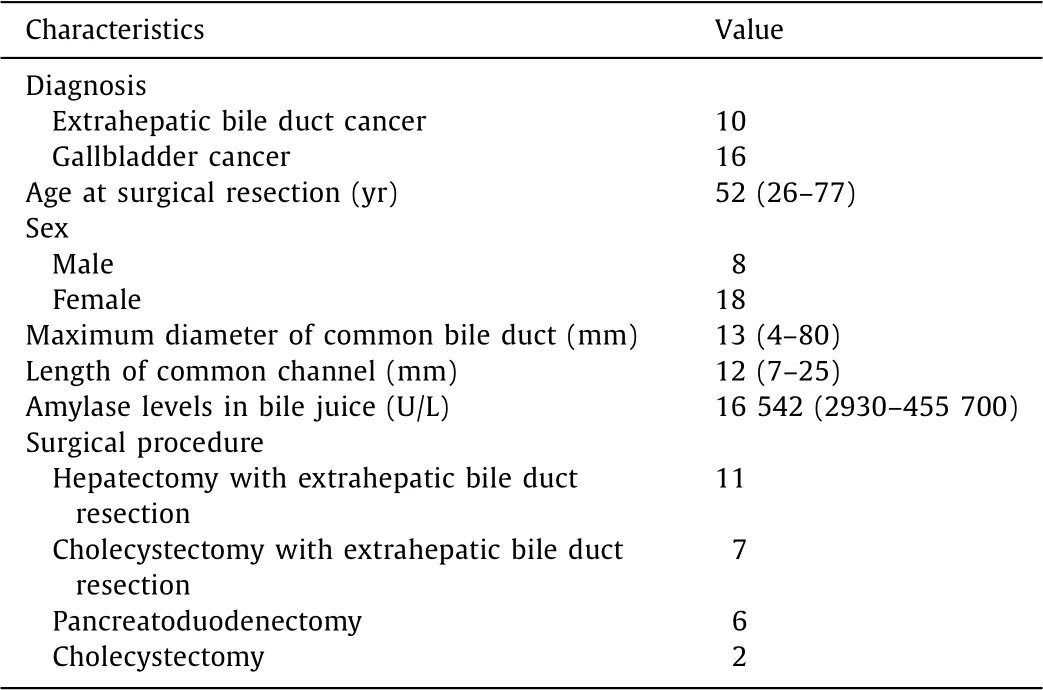

Table 1 Characteristics of patients of biliary cancer with PBM ( n = 26).

Fisher’s exact probability tests were used for categorical vari- ables. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Sur- vival rates were assessed using the Kaplan-Meier test and statis- tical significance was determined using log-rank tests. Significant univariate factors in the bile duct or gallbladder cancer groups were included in a multivariate logistic regression model. All sta- tistical analyses were performed using the software JMP pro 13.0.0 (SAS Institute, USA).

During the study period, 533 consecutive patients with biliary cancer underwent surgical resection at our institution. Of these pa- tients, 62 were excluded as they underwent palliative resection. The remaining 471 patients, including 318 and 153 patients with extrahepatic bile duct and gallbladder cancer, respectively, were el- igible for this retrospective study. Twenty-six of them (5.5%) were PBM-related, including 10 with extrahepatic bile duct and 16 with gallbladder cancer. The demographics and clinical characteristics of these patients are summarized in Table 1 .

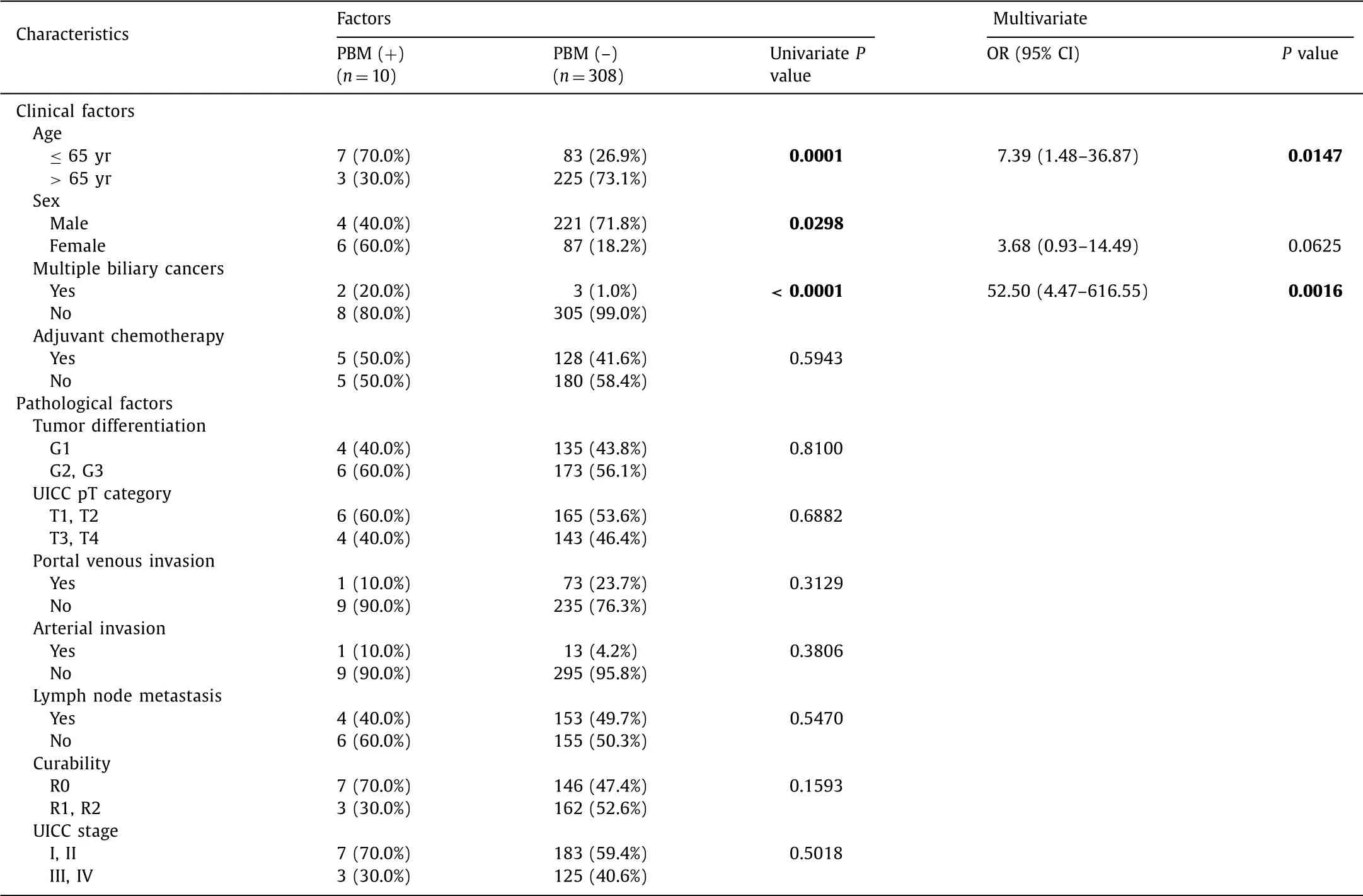

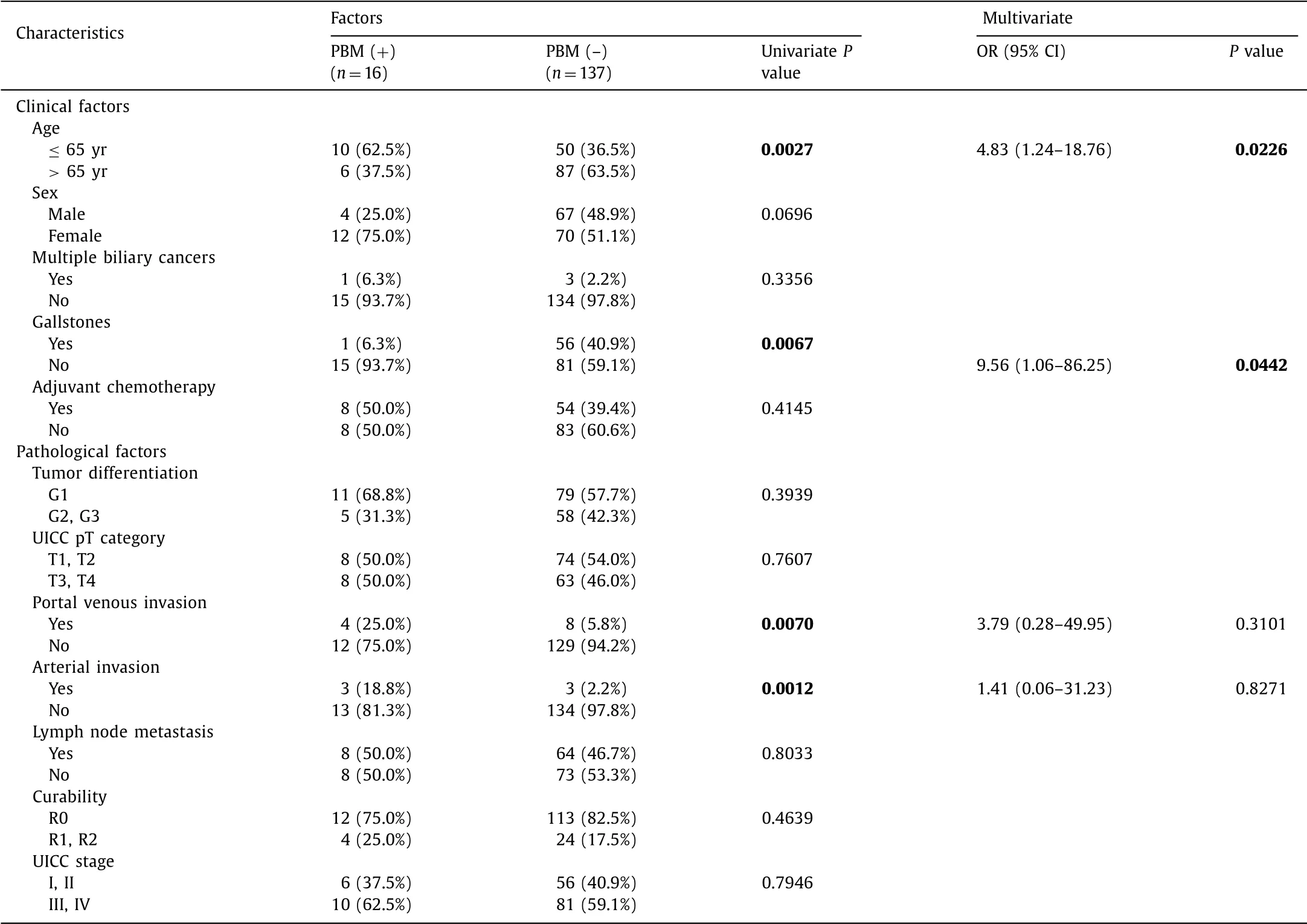

The results of the univariate and multivariate analysis of the clinicopathological features of patients with extrahepatic bile duct and gallbladder cancers with or without PBM are shown in Tables 2 and 3 , respectively. Extrahepatic bile duct cancer patients with PBM were significantly younger at surgical resection and had a higher frequency of female patients and multiple biliary cancers compared with those without PBM. Gallbladder cancer patients with PBM were also significantly younger at surgical resection, and had a lower frequency of gallstones and high frequency of portal venous and arterial invasion than those without PBM. In contrast, no pathologic features, including tumor differentiation, pT (patho- logical T) category, lymph node metastasis and UICC stage, were significantly different between the two groups. The multivariate analysis revealed that age older than 65 years and having multiple biliary cancers were independent features of extrahepatic bile duct cancer with PBM, and age older than 65 years and less of having gallstones were independent features of gallbladder cancer with PBM. There was no significant difference in overall survival (OS) in patients with extrahepatic bile duct cancer with and without PBM; five-year survivals were 40.0% and 34.8%, respectively. Sim- ilarly, there was no significant difference in OS in patients with gallbladder cancer with and without PBM; five-year survi vals were 41.7% and 47.4%, respectively.

Table 2 Comparison of clinicopathological factors of patients of extrahepatic bile duct cancer with or without PBM.

Table 3 Comparison of clinicopathological factors of patients of gallbladder cancer with or without PBM.

Morine et al. demonstrated that among patients with dilated biliary tract with PBM, the age of cancer onset was 60.1 ±10.4 years in gallbladder, 52.0 ±15.0 years in bile duct [2] . Since biliary cancer frequently occurs at around 70-79 years of age in Japan, biliary cancer associated with PBM is presumed to occur at the younger ages. Examinations of only surgically resected cases, as in the current study, revealed that the age difference between pa- tients with biliary cancers associated with PBM and those not as- sociated with PBM was about 20 years in extrahepatic bile duct cancer and 10 years in gallbladder cancer.

Multiple biliary cancers observed in PBM patients include mul- tiple lesions in the extrahepatic bile duct as well as double cancer of the bile duct and gallbladder [6] . These findings indicate that the locations of cancer development are spread throughout the en- tire bile outflow pathway whereas exposure to refluxed pancreatic juice is attributed to PBM. Therefore, preoperative detailed exam- ination of the entire biliary tract and long-term follow-up are re- quired in PBM patients.

Gallstones are a clinical feature of biliary cancer, even though there was a significant difference only in our analysis in gallblad- der cancer. Although the gallstone retention rate is high in patients with gallbladder cancer, it is low in gallbladder cancer patients with PBM. Kamisawa et al. reported a 62% rate of concurrent gall- stones in patients with gallbladder cancer, whereas this rate was significantly lower (9%) in PBM patients [7] which were consistent with our study; only one gallbladder cancer patient (6.3%) with PBM had gallstones. It remains unknown why gallstone retention rates in gallbladder cancer patients with PBM are low, but the ori- gin of gallstones, including gallbladder mucosa inflammation, bac- terial infection and bile juice stasis, may play a role.

The characteristics of the carcinogenetic pathway of PBM have not been fully clarified. In fact, pathologic changes such as hyper- plasia, dysplasia, and subsequent carcinoma, which may be caused by repeated injury and repair of the bile duct mucosa due to refluxed pancreatic juice since childhood, are frequently observed in cases with PBM [8] . Epithelial hyperplasia with K-ras mutation in the gallbladder mucosa has been identified during childhood in patients with PBM, although metaplasia and dysplasia are rarely observed [9] . Epithelial hyperplasia is often seen in non- cancerous and non-dysplastic gallbladder mucosa in patients with PBM, while these pathologic changes are not commonly observed in gallbladder cancer patients without PBM [10] . These results suggest the involvement of a hyperplasia-dysplasia-carcinoma sequence in the carcinogenesis of gallbladder cancer associated with PBM, possibly leading to cancer in younger patients and the occurrence of synchronous and metachronous multiple gallbladder cancers.

This study had an inherent limitation owing to its retrospective design, small number of PBM patients, and single center evalua- tion. Further large, multicenter, prospective cohort study is needed to clear the features of these rare congenital anomaly and deter- mine the appropriate surgical strategy for biliary cancer with PBM.

In conclusion, this study identified the clinicopathological fea- tures of surgically resected extrahepatic bile duct cancer cases with PBM: younger than 65 years and high frequency of multiple biliary cancer; the features of PBM-related gallbladder cancer included younger than 65 years and low frequency of having gallstones, and high frequency of portal venous and arterial invasion. There was no significant difference in prognosis after tumor resection between the patients with and without PBM.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Tsukasa Takayashiki:Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.Hideyuki Yoshitomi:Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation.Katsunori Furukawa:Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation.Satoshi Kuboki:Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation.Masaru Miyazaki:Method- ology.Masayuki Ohtsuka:Project administration.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University (No. 2715).

Competing interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- MEETINGS AND COURSES

- Living-donor liver transplantation for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan: Current situations and challenge

- Deliberate external pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy performed in the setting of acute pancreatitis, and its internalization through fistula-jejunostomy

- Immune checkpoint inhibitor for hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after liver transplantation

- Hypothermic oxygenated perfusion for a steatotic liver graft

- Postoperative negative-pressure drainage through a PEG tube can prevent pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy