Postoperative negative-pressure drainage through a PEG tube can prevent pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy

2020-03-03AleksnderSowierPrzemysPydSestinSowierJonnKpturzkAnnRykJcekBilecki

Aleksnder Sowier , Przemysłw Pyd , , Sestin Sowier , Jonn Kpturzk , Ann Ryk , Jcek Bilecki

a Department of General, Minimally Invasive and Trauma Surgery, Franciszek Raszeja City Hospital in Poznan, ul. Mickiewicza 2, 60-834 Poznan, Poland

b Department of General and Endocrine Surgery and Gastroenterological Oncology, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, ul. Przybyszewskiego 49, 60-355 Poznan, Poland

Postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) is a well-known com- plication after pancreatoduodenectomy [1] . It is difficult to pre- vent due to a number of factors. The very placement and tight- ening of sutures in pancreatic tissue is challenging. Perfusion of the anastomosis edges is unpredictable. Another risk factor is the large amounts of fluids (comprising gastric and intestinal secre- tions, bile, and pancreatic juice) collected in the intestine near the pancreatic anastomosis, which increase the pressure in the first loop of the anastomosed intestine, and may ultimately rupture the pancreatoenteric anastomosis. Effective peristalsis, required to pass these fluids to subsequent sections of the intestine, takes time to return after such an extensive procedure. Increased pressure in the intestinal loop may also contribute to ischemia, by increas- ing the tension of the intestinal wall, constricting or even block- ing its blood vessels. All these are aggravated by the chemical ef- fects of intestinal contents. Any surgical errors may add the risk of POPF. The most significant risk factors include pancreatic duct size smaller than 3 mm; soft pancreatic parenchyma, ampullary, duode- nal, cystic, or islet cell pathology; and massive intraoperative blood loss. Based on these factors a fistula risk score was devised to as- sess the probability of POPF formation after pancreatoduodenec- tomy [2] .

Methods are investigated to reduce these risks at all stages of perioperative management including pharmaceutically decreased secretion [3] , correct surgical management [4] , and drained gas- trointestinal content [5] . Currently, negative-pressure gastrointesti- nal drainage seems to be the most promising solution. In this study, a novel plan of negative-pressure therapy was proposed in the entire postoperative period after pancreatoduodenectomy.

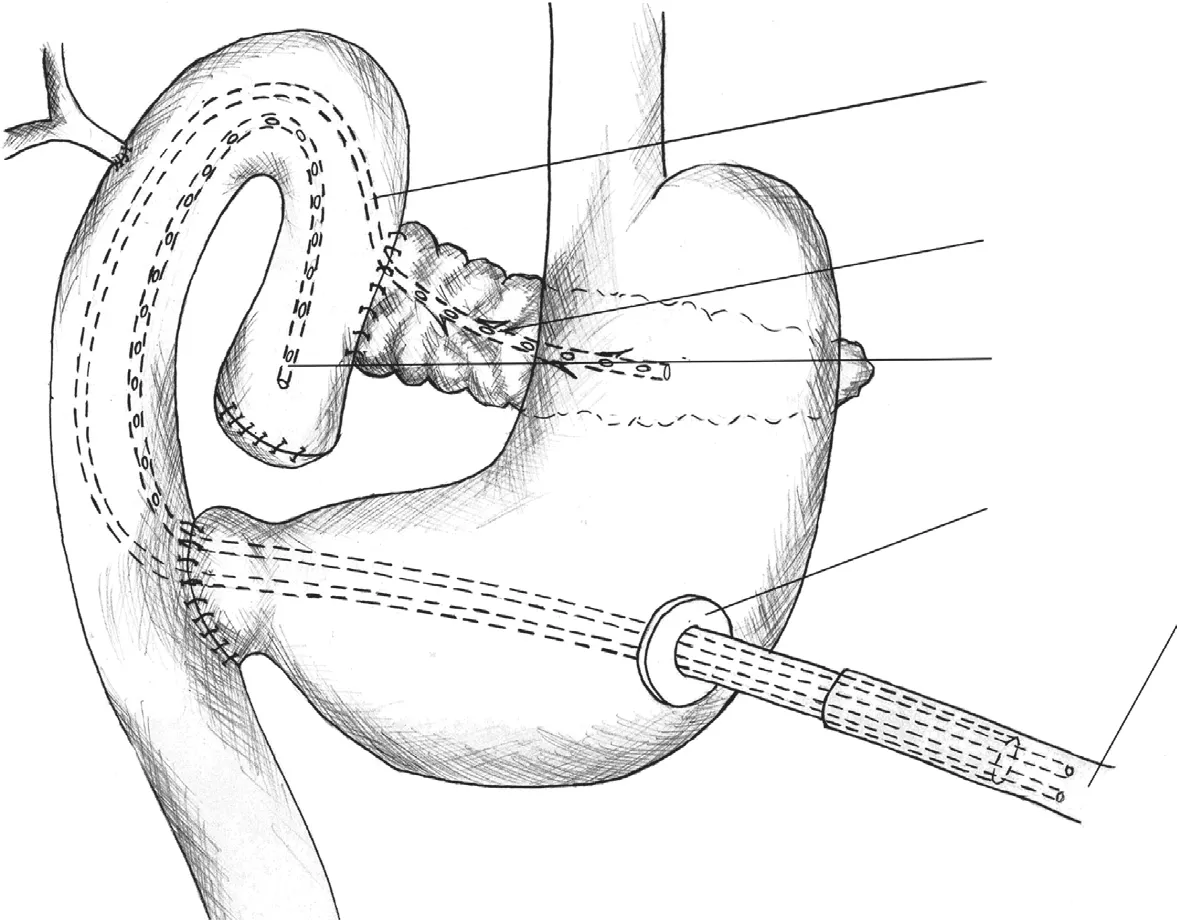

The method involves applying intermittent suction drainage of gastrointestinal content simultaneously to the area of all three anastomoses and the pancreatic duct in the postoperative pe- riod after the Traverso-Longmire pylorus-preserving pancreatoduo- denectomy ( Fig. 1 ). The technique was used in 5 consecutive patients (median age: 65 years) admitted to our hospital in 2016-2017. Indications for surgery included: pancreatic head cancer in 2 cases and cancer of the ampulla of Vater in 3 cases. Consent for the modified procedure was obtained from all the patients.

In preparation for the surgery, a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube was placed. The subsequent procedure was a typical pancreatoduodenectomy. Subsequently the pancre- atic stump was anastomosed to the side of the jejunum. A sin- gle layer of interrupted sutures was placed to achieve invagina- tion of the pancreatic stump into the jejunum. Once the poste- rior row of pancreatojejunal sutures had been placed, a hydrophilic guidewire was inserted into the pancreatic duct, the length of the duct was measured, and the appropriate length of the pancreatic stent was selected. Subsequently, the perforated stent was inserted over the guidewire. Then, a catheter was attached to the exter- nal part of the stent so that the connection remained inside the pancreatic duct. The catheter blocked all the side openings of the stent outside of the pancreatic parenchyma and acted as an addi- tional seal in the duct. Subsequently, the other end of the catheter was passed through the intestinal loop towards the enterotomy created in preparation for the gastrointestinal anastomosis, and then and brought out through the PEG tube. The pancreatoenteric anastomosis was completed by placing sutures (4/0 monofilament, absorbable) on the anterior wall of the anastomosis. Then, the choledochoenteric and gastroenteric anastomoses were performed. Another perforated catheter was inserted, whose peripheral end was placed inside the jejunum, between the pancreatic and biliary anastomoses, while the other end was brought out through the PEG tube. Two peritoneal drains were left after the pancreatoduo- denectomy: one placed below the hepatoduodenal ligament and the anastomoses, and the other placed in the Douglas cavity. Addi- tionally, a feeding tube was inserted - in 3 cases through the PEG tube and in 2 cases through the nose - with its distal end placed in the intestinal loop approximately 50 cm below the most dis- tal anastomosis. Intermittent suction drainage at a negative pres- sure of approximately 20-30 mmHg was applied immediately af- ter the procedure, simultaneously to the PEG tube and to both catheters. This suction drainage was maintained for 7-9 days, a sufficient time for effective peristalsis to return. The day after suc- tion drainage had been discontinued, all the drains passed through the PEG tube, were removed. After the return of peristalsis, enteral nutrition was initiated. The lower abdominal drain was removed 3-4 days postoperatively. The upper one was removed the day after the removal of the PEG drains. Patients were readmitted 3-4 weeks after discharge for one day, at which time follow-up exam- inations were performed and the gastrostomy was closed.

Table 1 Perioperative management parameters.

Fig. 1. Diagram of suction drainage of gastrointestinal contents.

Detailed results are shown in Table 1 . The PEG tube was placed on the day before the surgery in 3 cases, and on the day of the surgery in 2 cases. The diameter of the stent was 8.5 F in 4 cases and 7 F in 1 case. All patients survived the operation, and were discharged on postoperative day 10-16. In all the patients, effective suction drainage of pancreatic duct content and intestinal content was performed for 7 days after the surgery through the PEG tube, with a daily drainage volumes of 30 0-90 0 mL (median 60 0 mL). None of the patients experienced vomiting, with some patients reporting mild nausea only. None of the patients showed symp- toms of anastomosis leakage, and the peritoneal drainage tubes only drained serosanguineous fluid.

The role of drainage in POPF prevention has been broadly dis- cussed. The debate concerns the very need for drainage [6] , the type of drains used, duration of drainage, and internal versus ex- ternal drainage [7] . Suction techniques are particularly promising in fistula prevention [8] . Number of reports indicated that exter- nal drainage of the pancreatic duct stent reduces the risk of fis- tulas [7,9,10] . Thus, the drainage concept presented here is not a new one - the novelty consists in using a PEG tube for the post- operative suction drainage, and in the way the procedure is con- ducted. The suction drainage allows for ongoing removal of accu- mulated gastric, intestinal, and pancreatic content from the area of the anastomoses, and the feeding tube enables the initiation of enteral nutrition as soon as peristalsis is restored. The pressure in- side the entire upper digestive tract is reduced. Tissue edges ad- here better, while tension in the intestinal wall is reduced. Peri- stalsis can be restored quicker, as the gastrointestinal walls are not distended by the accumulated content. The primary advantage of using a PEG tube is the avoidance of passing through the intestinal wall and then to the outside of the body through the abdominal wall, or bringing the catheters out through the nose. The former procedure may result in intestinal content leakage and require the intestinal loop to be pulled up and sutured to the abdominal wall. The latter presents significant inconvenience to the patient. When using a PEG, pancreatic duct drainage and intestinal drainage can be performed simultaneously, with a single route for both drains. Additionally, if the diameter of the PEG is sufficient it is also pos- sible to insert a feeding tube through the PEG tube. When patients are fed using the feeding tube after effective peristalsis is restored, the burden on the anastomoses is reduced. Patients become well- nourished faster, which improves their wellbeing, as well as their willingness and ability to cooperate with medical staff in the treat- ment process. This should ultimately contribute to faster healing of the anastomoses and the surgical wound, shorter hospitalization, and faster recovery [11] .

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Aleksander Sowier:Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition.Przemysław Pyda:Methodology, Funding acquisition, Writing - original draft, Supervision.Sebastian Sowier:Funding ac- quisition, Writing - original draft, Methodology, Resources.Joanna Kapturzak:Writing - review & editing, Formal analysis, Resources.Anna Rybak:Writing - review & editing, Data curation.JacekBialecki:Visualization, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Since the presented method is a composition of well- established procedures therefore approval from a bioethics com- mittee was not sought.

Competing interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the sub- ject of this article.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- MEETINGS AND COURSES

- Living-donor liver transplantation for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan: Current situations and challenge

- Clinicopathological features and prognosis of surgical resected cases of biliary cancer with pancreaticobiliary maljunction

- Deliberate external pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy performed in the setting of acute pancreatitis, and its internalization through fistula-jejunostomy

- Immune checkpoint inhibitor for hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after liver transplantation

- Hypothermic oxygenated perfusion for a steatotic liver graft