lnterpretation of the development of neoadjuvant therapy for gastric cancer based on the vicissitudes of the NCCN guidelines

2020-01-16XianZeWangZiYangZengXinYeJuanSunZiMuZhangWeiMingKang

Xian-Ze Wang, Zi-Yang Zeng, Xin Ye, Juan Sun, Zi-Mu Zhang, Wei-Ming Kang

Xian-Ze Wang, Zi-Yang Zeng, Xin Ye, Juan Sun, Zi-Mu Zhang, Wei-Ming Kang, Department of General Surgery, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Science and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China

Abstract

Key words: Gastric cancer; Locally advanced gastric cancer; Neoadjuvant therapy;Neoadjuvant chemotherapy; Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy; NCCN guidelines

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer (GC) is the most common tumor of the digestive system. GLOBOCAN estimated approximately 1.034 million newly diagnosed GC cases worldwide in 2018,which accounted for 5.7% of all tumors and ranked fifth among all cancers. GC is also the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths, as 0.783 million deaths were caused by GC in 2018, which accounted for 8.2% of all cancer deaths[1]. The incidence of GC in Asia is much higher than that in other countries and regions. The incidence of GC in East Asia is approximately 32.1/100000, and the mortality rate is as high as 13.2/100000[1]. Moreover, the current situation of GC in China is far more serious.First, the number of GC patients in China accounts for a substantial proportion of all GC cases worldwide, with approximately 679000 newly diagnosed cases and 498000 deaths each year[2,3]. Second, the early diagnosis of GC in China is still in its initial stage. Patients with stage II-III GC account for 58.0% of the GC cases in China, while in South Korea and Japan, patients with stage II-III account for only 22.5% and 24.9%of all GC cases, respectively[4,5]. As the 5-year survival rate of patients with locally advanced gastric cancer (LAGC) plunges dramatically, ways to improve the treatment effect and prognosis of these patients have become a primary focus in China and even worldwide.

THE RISE OF NEOADJUVANT THERAPY FOR GC

Surgery is the most effective treatment for nonmetastatic GC, and the cure rate for stage T1 cancer can reach 90% after surgery. However, many patients with LAGC will experience tumor recurrence within 1 year after surgery, even those with R0 resection,and the 5-year survival rate of these patients is less than 50%[6,7]. Most scholars believe that surgical excision alone cannot achieve satisfactory outcomes in LAGC, and thus neoadjuvant therapy (NAT) was developed.

The concept of NAT was first proposed by Frei in 1982[8], and it has also been referred to as preoperative chemotherapy. In the 1990s, Wilke, Plukker, Mai, and other scholars began to apply preoperative chemotherapy in the treatment of GC.They found that preoperative chemotherapy could achieve tumor downstaging,improve the tumor resection rate, and prolong the postoperative survival time of LAGC patients[9-11]. The above study served as the prelude to NAT for LAGC, but conceptually, they should be considered as the conversion therapy. Currently, NAT is applicable to LAGC patients with resectable lesions at initial diagnosis. The purpose of NAT is to further reduce the lesion size, improve the R0 resection rate, inhibit micrometastases, reduce the risk of tumor recurrence, and determine the sensitivity of patients to the corresponding treatment in advance[9,12,13].

NAT strategies for LAGC patients have been developed and continuously improved in recent decades. Studies have mainly focused on the patterns, indications,and the optimal regimens of NAT, as well as the response assessment and additional management after NAT and surgery. We will elaborate on the development and major breakthroughs of NAT for GC based on the vicissitudes of the NCCN guidelines for GC, and assess the future of this therapy.

THE PATTERN OF NAT FOR LAGC

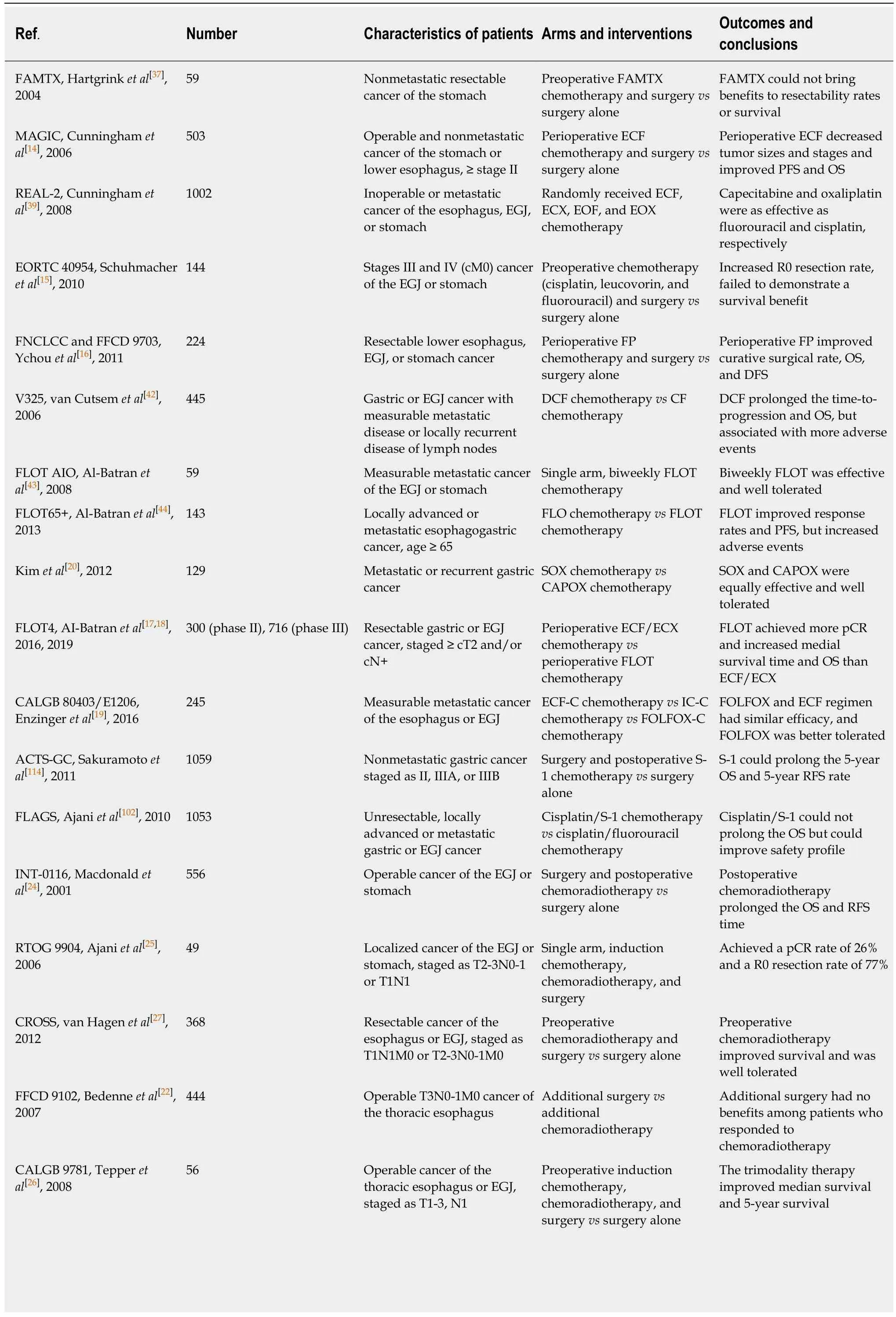

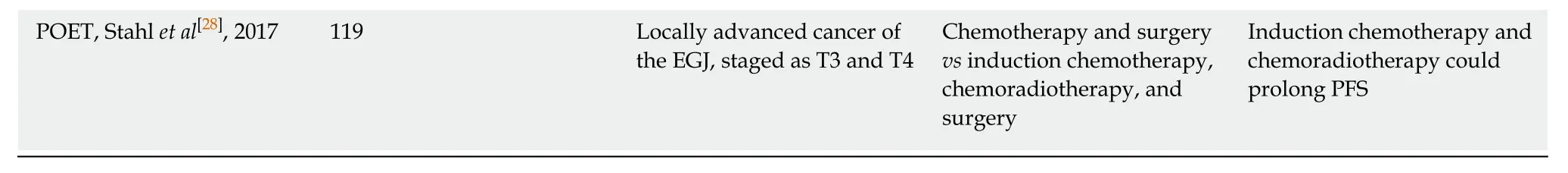

Most NAT schemes referred to adjuvant therapy for gastric cancer. Currently, the NCCN guidelines recommend both perioperative chemotherapy (category 1) and preoperative chemoradiotherapy (category 2B) as alternatives to NAT for LAGC (see related studies and detailed recommendations in Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1 lmportant studies of neoadjuvant therapy for gastric cancer

FAMTX: Fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and methotrexate; ECF: Epirubicin, cisplatin, and fluorouracil; ECX: Epirubicin, cisplatin, and capecitabine; EOF:Epirubicin, oxaliplatin, and fluorouracil; EOX: Epirubicin, oxaliplatin, and capecitabine; DCF: Docetaxel, cisplatin, and fluorouracil; CF: Cisplatin and fluorouracil; FLO: Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin; FLOT: Docetaxel, fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin; SOX: S-1 and oxaliplatin; CAPOX:Capecitabine and oxaliplatin; ECF-C: ECF and cetuximab; IC-C: Irinotecan, cisplatin, and cetuximab; FOLFOX-C: Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, leucovorin, and cetuximab; EGJ: Esophagogastric junction; pCR: Pathological complete regression; PFS: Progression-free survival; OS: Overall survival; RFS: Relapse-free survival.

Pre/perioperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy

Although Wilkeet al[10]have revealed the positive effect of preoperative chemotherapy on LAGC patients through various studies, it was not until 2006 that the Medical Research Council Adjuvant Gastric Infusional Chemotherapy (MAGIC) study in the United Kingdom verified this conclusion through a large-scale randomized controlled trial (RCT). The MAGIC study confirmed that perioperative chemotherapy could achieve tumor downstaging and improve the R0 resection rate in patients with resectable LAGC. Additionally, perioperative chemotherapy and surgery can significantly prolong the progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) of patients compared with surgery alone[14]. This landmark study prompted the NCCN guidelines to incorporate preoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) into the standard treatment procedures for LAGC in 2007.

The conclusions of the MAGIC study were subsequently validated by other clinical trials. In 2010, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Randomized Trial 40954 (EORTC 40954) study confirmed the significant effect of preoperative chemotherapy in improving the R0 resection rate (81.9%vs66.7%,P=0.036) and reducing the lymph node metastasis rate (61.4%vs76.5%,P= 0.018) of LAGC patients[15]. The Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte contre le Cancer and Fédération Francophone de Cancérologie Digestive 9703 (FNCLCC and FFCD 9703)study published in 2011 not only reached similar conclusions, but also verified the advantages of perioperative chemotherapy in prolonging the 5-year disease-free survival rate (DFS) and OS of patients compared with surgery alone[16]. The FLOT4(Fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin, docetaxel) study published in 2016 and 2019 indicated that NACT can achieve a high pathological complete regression (pCR) rate and significantly prolong the survival of patients[17,18]. At this point, pre/perioperative NACT became a mature scheme with definite efficacy and sufficient evidence and has been listed as a category 1 recommendation in the NCCN guidelines since 2007 (Table 2).

The specific schedules of NACT proposed by the MAGIC, FNCLCC and FFCD 9703, and FLOT4 trials all consist of preoperative and postoperative chemotherapy(also known as perioperative chemotherapy). However, due to the dissatisfactory commencing rates of postoperative chemotherapy in these studies (137/209 (65.6%),54/109 (49.5%), and 78/119 (65.5%) for MAGIC, FNCLCC and FFCD 9703, and FLOT4 studies, respectively) and even lower completion rates (104/209 (49.8%), 25/109(22.9%), and 60/119 (55.0%), respectively), the benefits of postoperative chemotherapy were inconclusive. Thus, NCCN guidelines only initially recommended preoperative chemotherapy as the primary treatment for certain LAGC patients, and this recommendation was revised to include perioperative chemotherapy when more evidence became available in 2016.

Although undisputed benefits of perioperative chemotherapy have been presented by many clinical trials (Table 1), the category 1 recommendation made by NCCN guidelines was mainly derived from the above three landmark studies (the MAGIC,FNCLCC and FFCD 9703, and FLOT4 studies)[14,16,17]. Sequentially, the dosing schedules of recommended regimens were also based on these three or their relevant studies (except for fluorouracil and oxaliplatin regimen, Table 2)[19-21].

Preoperative neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy

Chemoradiotherapy plays an important role in treating esophageal cancer. The Fédération Francophone de Cancérologie Digestive 9102 (FFCD 9102) study reported that, for locally advanced thoracic esophageal cancer patients who responded to chemoradiation, the additional surgery could provide no benefit comparing with the continuation of additional chemoradiation[22]. Due to the successful treatment of esophageal cancer with chemoradiotherapy, scholars attempted to expand this treatment to GC, especially to lower esophageal and esophagogastric junction (EGJ)cancers[23].

Table 2 The vicissitudes of the recommendation categories of different neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimens in the NCCN gastric cancer guidelines

In 2001, the Intergroup-0116 (INT-0116) study found that postoperative chemoradiotherapy could significantly prolong the median OS of patients with EGJ or gastric adenocarcinoma (36 movs27 mo,P= 0.005) compared with surgery alone[24].In 2006, the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 9904 (RTOG 9904) study reported that preoperative induction chemotherapy and sequential chemoradiotherapy could achieve a high pCR rate and R0 resection rate in patients with localized gastric adenocarcinoma[25]. Subsequently, both of the large-scale clinical trials in the United States (Cancer and Leukemia Group B 9781 study, CALGB 9781 study) and the Netherlands (Chemoradiotherapy for Oesophageal Cancer Followed by Surgery Study, CROSS study) confirmed that preoperative chemoradiotherapy could indeed achieve a satisfactory pCR rate and improve the R0 resection rate, and it could also prolong the median survival time and 5-year survival rate of patients with lower esophageal and EGJ cancers[26,27]. As a result, preoperative chemoradiotherapy was recommended as the preferred approach for localized EGJ adenocarcinoma (for Siewert type III EGJ cancer, hereinafter the same) according to the NCCN guidelines from 2012 to 2014[27]. In 2017, the PreOperative therapy in Esophagogastric adenocarcinoma Trial concluded that preoperative induction chemotherapy and chemoradiotherapy might have better therapeutic effects on EGJ cancer than preoperative chemotherapy alone, which would significantly improve the local PFS after resection (P= 0.01) and had a trend in prolonging the OS of patients (39.5%vs24.4%,P= 0.055)[28].

However, most scholars still believe that, since the incidence, geographical distribution, etiology, disease course, and biological behavior of EGJ cancers are different from those of true gastric (noncardia) cancers, the overall efficacy of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy remains inconclusive[29]. Since the effects of preoperative chemoradiotherapy in resectable GC were only proposed by small-scale and single-arm studies, the regimens and dosing schedules listed in NCCN guidelines were based on trials that recruited esophageal and/or EGJ cancers patients[22,25-27,30-35].Therefore, the recommendation category of preoperative chemoradiotherapy remains in category 2B according to the latest NCCN guidelines. More than that, since there have not been enough studies compared the effect of pre/perioperative chemotherapy with chemoradiotherapy, the preferred recommendation of preoperative chemoradiotherapy for localized EGJ (Siewert type III) adenocarcinoma was also deleted in the 2015 NCCN guidelines. In the following sections, we will focus more on the development of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for LAGC.

THE APPLICABLE POPULATION OF NAT

Studies that specifically focused on the applicable population of NAT are still lacking.However, since NAT aims to improve the surgical outcomes in LAGC patients and the cure rate of T1 gastric cancer could reach 90% after surgery, most clinical trials enrolled patients with tumor ≥ T2/T3 and with/without lymph node metastasis invariably. Meanwhile, cytotoxic agents used in NACT are more efficient for metabolically active and/or proliferating tumor cells. Since the proliferation of tumor cellsin vivo, which conforms to the Gompertzian model[36], will be retarded along with the growth of tumor and the accumulation of necrosis and metabolites, the sensitivity to chemotherapy will also decline. These concepts serve as the basis for establishing the applications of NAT and reflect its original intention.

The NCCN guidelines have made minor alterations on the applicable population of NAT in the past decade. NAT was initially recommended for patients who are medically fit and with potentially resectable LAGC with clinical stage ≥ T2 or N+.Since 2012, the guidelines have neglected lymph node metastasis and recommend NAT for the abovementioned patients with clinical stage ≥ T2.

THE EVOLUTION OF NEOADJUVANT CHEMOTHERAPY REGIMENS

The efficacy and side effect must be weighted before performing NACT. Two-drug regimens were preferred according to the NCCN guidelines in principle because of their lower toxicity. And three-drug regimens may be applied in medically fit patients with access to frequent evaluation during treatment, to ensure that they can still tolerate surgery after NACT.

ECF and ECF modifications

Fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and methotrexate (FAMTX) was one of the first attempts used in NACT for gastric cancer, but it failed to bring benefits to LAGC patients[37].Some scholars attributed the failure to the low effectiveness of this regimen, and Webbet al[38]did confirm that the efficacy of epirubicin, cisplatin, and fluorouracil(ECF) significantly surpassed that of FAMTX in patients with unresectable GC. With forethought, Cunninghamet al[39], one of the originators of the ECF regimen,conducted the MAGIC study with landmark significance.

The MAGIC study enrolled 503 patients with nonmetastatic and operable lower esophageal cancer or GC who randomly received perioperative chemotherapy (ECF regimen, 3 cycles before and after surgery) and surgery or surgery alone. The results indicated that preoperative chemotherapy did not increase either postoperative complications or 30-day mortalities. Moreover, NACT resulted in tumor downstaging(T stage,P= 0.002; N stage,P= 0.01) and a higher R0 resection rate (79.3%vs70.3%,P= 0.03). The PFS (P< 0.001) and 5-year survival rates (36.3%vs23.0%,P= 0.009) were also improved significantly in patients who received NACT. Therefore, the NCCN guidelines began to adopt ECF as the standard regimen for neoadjuvant chemotherapy (category 1) in 2007.

To control the adverse effects and clinical practice difficulties of the ECF regimen,Cunninghamet al[39]initiated the Randomized ECF for Advanced and Locally Advanced Esophagogastric Cancer 2 (REAL-2) study in 2000[40]. Based on the ECF regimen, the REAL-2 study inspected the substitution of oxaliplatin (O) and capecitabine (X) for cisplatin (C) and fluorouracil (F) in patients with inoperable or metastatic esophageal, EGJ, or gastric cancer. The results confirmed that the incidences of side effects among ECF, ECX, EOF, and EOX (E, epirubicin) were similar(P> 0.05); it was also found that the EOX regimen was superior to the ECF regimen in prolonging the OS (P= 0.02) of patients. Moreover, the advantages of oral administration of capecitabine and the needlessness of persistent intravenous hydration of oxaliplatin reduce the admission time and frequency for patients. The REAL-2 study was published in 2008, and the three ECF modifications were subsequently adopted by the NCCN as the standard regimens (category 1). In addition, the substitutability between cisplatin and oxaliplatin, as well as infusional fluorouracil and capecitabine, was recognized by the guidelines. At this point,Cunninghamet al[39]established the first-line status of ECF and ECF modifications in GC NACT, which dominated for a decade (Table 2).

Fluorouracil and platinum-based regimens

Over the next five years, after the rise of the ECF and ECF modifications, few regimens could achieve comparable results or be tested by high-quality clinical trials.This situation finally changed in 2011, when YChouet al[16]published the phase III clinical trial FNCLCC and FFCD 9703 and proposed the fluorouracil and cisplatin (FP)regimen.

This two-drug regimen was reported by Rougieret al[41]in 1994 and achieved satisfactory results including a 77% surgical rate and a 60% R0 resection rate in patients with nonresectable LAGC. The FNCLCC and FFCD 9703 study further tested the efficacy of the FP regimen as NACT. In this study, 224 patients with resectable lower esophageal, EGJ, or gastric cancer were randomized to receive perioperative FP chemotherapy (2-3 cycles before surgery, 3-4 cycles after surgery) and surgery or surgery alone. The results indicated that preoperative FP chemotherapy can significantly improve the R0 resection rate of patients (84%vs74%,P= 0.04) and can achieve downstaging of lymph node metastasis (metastatic lymph node rate, 67%vs80%,P= 0.054). More importantly, the perioperative FP regimen significantly increased the 5-year OS (38%vs24%, log-rankP= 0.02) and 5-year DFS (34%vs19%,log-rankP= 0.003) of patients. Compared with ECF, the two-drug regimen of FP could not only achieve a similar effect in terms of improving the long-term prognosis of patients, but also had the advantages of reducing chemotherapy-related complications, especially grade 3 to 4 leukopenia[16].

In addition, the two-drug regimen of fluorouracil and oxaliplatin also came into view. Kimet al[20]verified that both S-1 + oxaliplatin and capecitabine + oxaliplatin had similar efficacy and good tolerance in patients with GC. In the CALGB 80403/E1206 study, Enzingeret al[19]also confirmed that the FOLFOX regimen(fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin) had similar effectiveness and better tolerance than the ECF regimen.

Considering the results of the MAGIC, FNCLCC and FFCD 9703, and other studies,as well as the safety priority principle of NACT, the two-drug regimens of fluorouracil and platinum (oxaliplatin/cisplatin) have gradually become the mainstream of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for LAGC. The FP regimen was adopted as a category 1 recommendation in the NCCN guidelines in 2013, and the fluorouracil +oxaliplatin regimen was also adopted in 2017 as a category 2A recommendation,while the recommendation categories of the ECF and ECF modifications were gradually demoted to 2A and 2B (Table 2).

FLOT regimen

After the MAGIC and FNCLCC and FFCD 9703 studies, the FLOT4 study published by German scholars Al-Batranet al[21]was considered as another landmark in the history of NACT for LAGC. The highlight of the FLOT regimen was the introduction of docetaxel.

The V325 study published in 2006 was the first large clinical trial that applied docetaxel in GC. Although the DCF regimen (docetaxel, cisplatin, and fluorouracil)used in this study improved the response rate to chemotherapy and prolonged the OS and PFS of patients with metastatic or locally recurrent disease, severe side effects have prevented it from being widely accepted[42]. On this basis, Al-Batranet al[43,44]proposed the FLOT (docetaxel, fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin) regimen in 2008, which combined docetaxel with a safer skeleton regimen of FLO (fluorouracil,leucovorin, and oxaliplatin). The effectiveness and safety of the FLOT regimen were then validated through two clinical trials. These results encouraged researchers to further challenge the classical ECF and ECF modifications with the newly developed FLOT regimen.

The FLOT4 phase II study published in 2016 enrolled 300 patients with resectable EGJ or gastric cancer. In that study, patients randomly received perioperative ECF/ECX or FLOT chemotherapy[17]. According to the study, the FLOT regimen not only significantly improved the surgical rate (93%vs81%,P= 0.01) and the R0 resection rate (85%vs74%,P= 0.02), but also promoted the downstaging of tumors (≤ypT2, 44%vs27%,P= 0.01). Most importantly, the pCR rate (tumor regression grade TRG1a) and the complete or subtotal regression rate (TRG1a/b) of the FLOT group were significantly higher than those of the ECF/ECX group (TRG1a, 16%vs6%,P=0.02; TRG1a/b, 37%vs23%,P= 0.02). The phase III portion of the FLOT4 study indicated that the incidence of serious side effects of the FLOT regimen was similar to the ECF/ECX regimen (27%vs27%), but the tumor resection rate (94%vs87%,P=0.001) and the R0 resection rate (85%vs78%,P= 0.0162) of the FLOT group (n= 356)were significantly higher than those of the ECF/ECX group (n= 360). The median OS(50 movs35 mo,P= 0.012) and median DFS (30 movs18 mo,P= 0.0036) were also significantly longer than those of the ECF/ECX group[18]. In view of the excellent pathological regression rate and the absolute advantages of FLOT over ECF/ECX, the NCCN guidelines adopted FLOT as the preferred regimen with a category 1 recommendation in 2018, and completely removed the ECF regimen and its modifications in the same year (Table 2).

From the domination of ECF and its modifications when NACT was developed in 2007 to the rally of the two-drug regimens of fluorouracil and platinum five years later, and the budding of the FLOT regimen in 2018, the development of chemotherapy drugs and the polishing of chemotherapy regimens have never stopped.

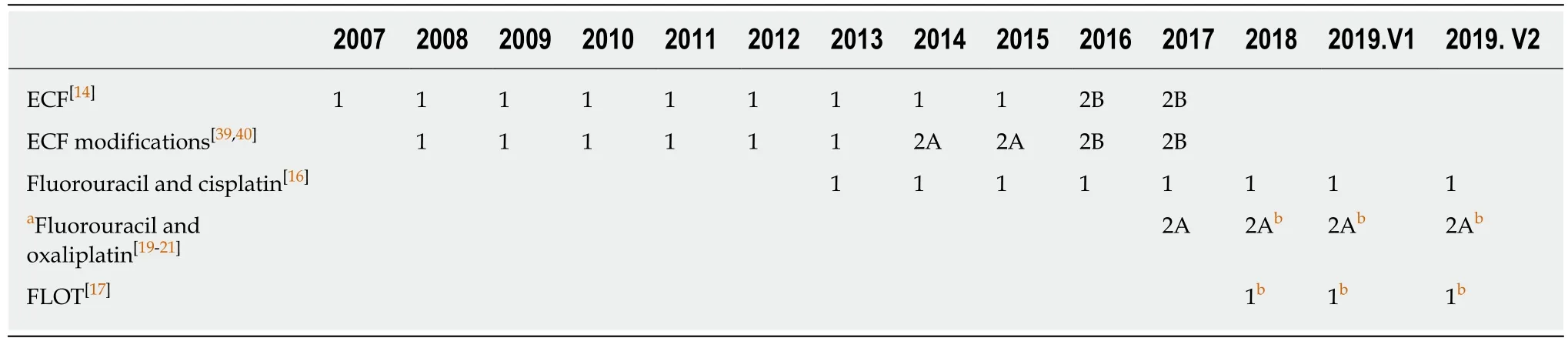

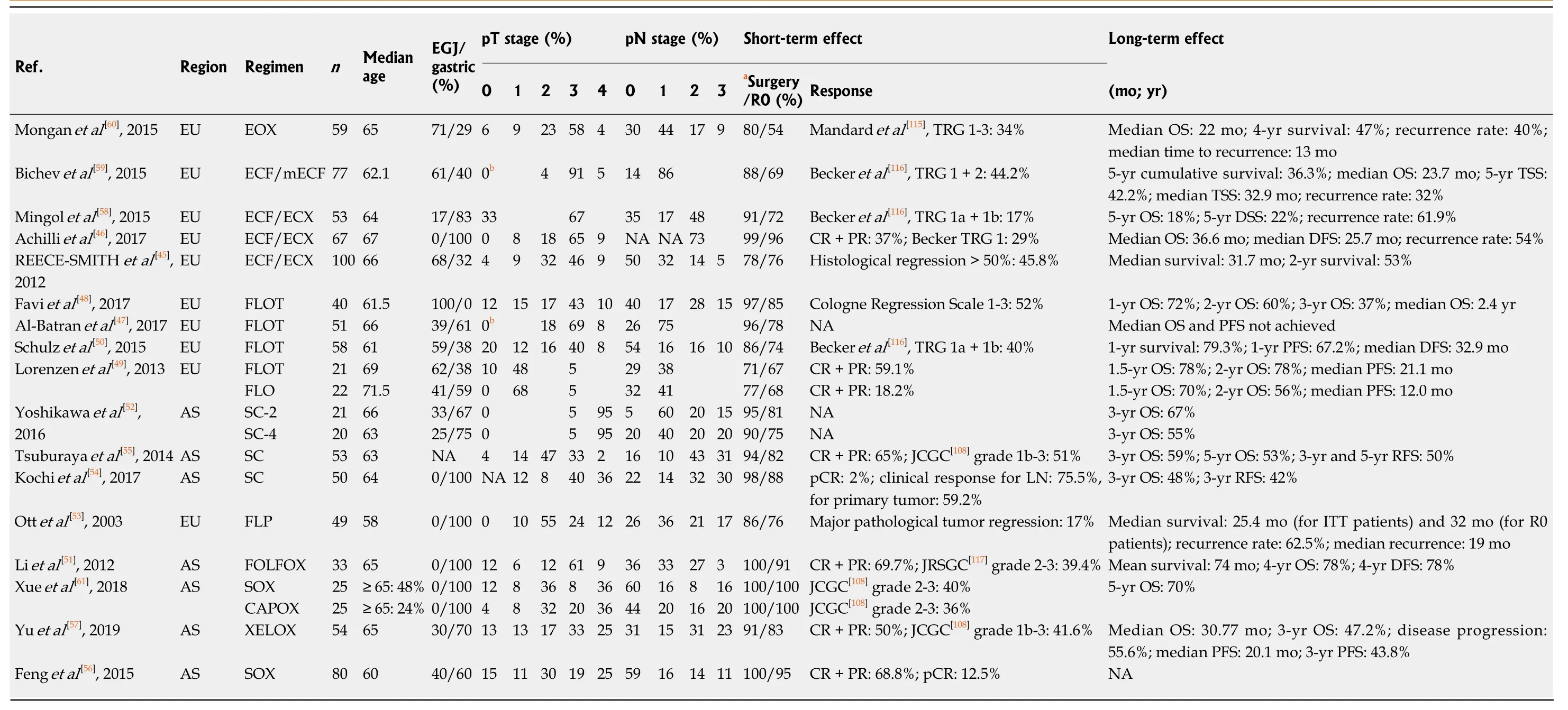

The efficacy of these regimens was further verified in many studies (Table 3).However, the absolute advantages of different regimens can hardly be concluded,because of the different regions, dosing schedules, completion rates, surgery/R0 resection rates and so on. Generally, the fluorouracil plus platinum regimens are more popular in Asia, while the ECF/ECF modifications and the FLOT regimen are widely accepted in Europe[45-61]. An excellent 4-year OS was achieved by Liet al[51]with perioperative FOLFOX regimen. In this prospective non-randomized study, LAGC patients received a total of 6 cycles of FOLFOX chemotherapy perioperatively or postoperatively. The clinical and pathological response rates of FOLFOX were 69.7%and 39.4%, respectively, and the 4-year OS, as well as the 4-year DFS, of the neoadjuvant arm was 78%[51]. Meanwhile, the highest pathological response rate was achieved by Faviet al[48]with preoperative FLOT regimen. Patients with advanced distal esophageal and EGJ cancer in this study received 3-6 cycles of FLOT chemotherapy before surgery, the tumor regression rate of Cologne regression grade 1-3 was 52%, and the 3-year OS was 37%[48]. Nevertheless, disease recurrences were still common among all the studies and regimens, with the recurrence rates ranging from 32% to 62.5% (Table 3).

RESPONSE ASSESSMENT AND ADDITIONAL MANAGEMENT FOR NAT

Since more and more patients have received neoadjuvant treatment in the past decade, the 2018 NCCN guidelines proposed a response assessment for those patients in order to improve additional management strategies.

According to the 2018 NCCN guidelines, a chest/abdomen/pelvis CT scan with contrast was used as the method to evaluate disease status. If the outcome showed persistent local disease, surgical treatment was preferred. For patients with unresectable or metastatic disease, and those who were not medically fit for surgery,palliative management was recommended. For patients with no evidence of disease,the guidelines allowed clinicians to perform surveillance on those who refused surgery on the premise that surgery was still preferred.

However, both “surveillance” and “no evidence of disease” are controversial in GC.First, the definition of “no evidence of disease” is vague, and CT scanning with contrast cannot evaluate the disease status accurately[62-64]. Second, although pCR is a predictor of a favorable prognosis, it is still not equivalent to the clinical cure[58,65,66].Finally, even if patients who achieved pCR after chemotherapy can be screened out by nonsurgical methods, sequential therapy should be recommended as an alternative to surgery[67]. Therefore, the 2019 NCCN guidelines contained major revisions in this chapter, the phrase “no evidence of disease” was deleted, and additional managements were recommended according to the resectability of the lesion. For patients with resectable tumors, surgery was still the preferred treatment, while for other patients, including those with nonresectable/metastatic lesions and those who were not medically fit for surgery, palliative care, but not surveillance, was recommended.

The postoperative treatment strategy for patients who received NAT was based on the cutting-edge of tumors and NAT modes. Due to the lack of direct studies that enrolled post-NAT patients, the recommendations proposed by the NCCN guidelines were derived from indirect studies with a relatively low level of evidence. The vicissitudes of this chapter were focused primarily on four aspects: (1) Before 2016, the stratification of postoperative NAT patients depended on their ypT and ypN stages,and only ypT2 and ypN0 patients were included in the low-risk group. In recent years, the status of lymph nodes has been elevated, and the current stratification is now only based on the presence of metastatic lymph nodes, partially according to the study of Smythet al[68]; (2) The unification of postoperative treatment became a trend,especially for those who achieved R0 resection after NAT. The latest guidelines now do not adhere to the stratification of R0 resected patients and gave highly unified treatment recommendations, partially due to the lack of relevant studies; (3)Chemoradiotherapy is now preferred for non-R0 resected patients after NAT. The INT-0116 study established the “operation and postoperative adjuvant chemoradiotherapy” pattern in North America. Based on this study, the NCCN guidelines recommend that non-R0 resected patients without preoperative chemoradiotherapy should receive postoperative chemoradiotherapy for additional management; and (4) Reconsiderations of selecting the postoperative NACT regimens. The NCCN guidelines previously recommended R1 resected patients who underwent NACT to receive the same NACT regimens after surgery, in order to ensure the integrity and unity of perioperative treatment. However, the 2019 guidelines only recommended those patients with R0 resection to continue their preoperative NACT regimens.

Table 3 Short-term and long-term effects of different pre/perioperative chemotherapy regimens

THE FUTURE OF NAT FOR GC

NAT is one of the breakthroughs of GC treatment in recent decades, and has the trend to become the standard strategy of this disease. However, the indications and strategies of NAT still need to be perfected, and researchers may gain ground in the following aspects in the future.

Above all, the validation of NAT in a wider range is necessary. The NCCN guidelines may only reflect a corner of NAT from the Western view, and the acceptability of NAT worldwide is still improving, especially in Asia. Chinese GC guidelines recommended that patients with advanced resectable GC (clinical stage III or above) could either receive surgery directly (Grade I recommendations) or receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy (Grade II recommendations)[69]. In Japan, preoperative chemotherapy has just been accepted in the latest guidelines for LAGC patients with bulky lymph nodes[70]. And in South Korea, the efficacy of preoperative chemotherapy and chemoradiotherapy for potentially resectable GC patients remains inconclusive[71].Meanwhile, numerous trials in Asia, such as JCOG0405, JCOG1002, NCT01515748,NCT01534546, NCT02555358, and NCT00252161[55,72,73], have provided or will provide more evidence about the best indications for NAT, and physicians should always be critical when adopting the recommendations from foreign guidelines.

Second, the enhancement and delicacy management of NACT are required.Fluorouracil and platinum have been used as skeleton regimens of NACT for years,and their efficiency and tolerance in patients have been tested. However, it is an eternal rule that old regimens will be eliminated and that the development of new drugs may further improve the prognosis of patients[74,75]. Besides traditional cytotoxic regimens, the development of targeted therapy, immunotherapy, and metabolism based anticancer therapy may help us usher in a new era of LAGC treatment.Targeted drugs such as trastuzumab (anti-HER2) and ramucirumab (anti-VEGF2)have shown potential in improving clinical outcomes for late staged patients[74-85].Immunotherapy, such as anti-PD-1/PD-L1 and anti-CTLA-4 drugs (nivolumab,pembrolizumab, avelumab, tremelimumab,etc.), adoptive cell therapy, and VEGF related cancer vaccine have also been evaluated in gastric cancer and have shown promising effects[86-92]. Studies about cancer metabolomics also provided new insights in cancer treatment. Drugs targeting at hexokinase II may intervene the glycolysis of tumor cells[93], and others that altered the metabolism of lipid, amino acid,etc. also presented exciting prospects in treating GCin vitro[94-96]. In addition, the continuous monitoring of NACT efficacy can also help to clarify the optimal operation timing for chemotherapy-sensitive patients, or it can encourage the termination of unnecessary treatment for chemotherapy-resistant patients in advance to avoid disease progression[97,98].

Besides, the individualized treatment and efficacy prediction of neoadjuvant chemotherapy may be a trend. It is true that the antitumor effects of cytotoxic drugs are extensive and without high selection, but the correlation between genetic traits and chemosensitivity may also be underestimated. Polymorphisms, gene mutations,and unique genetic backgrounds may lead to different response rates to the same chemotherapy regimen[99,100]. The advantages of the S-1 and cisplatin regimens reported by the SPIRITS (S-1 Plus cisplatin versus S-1 In RCT In the Treatment for Stomach cancer) study in Japan were not consistently concluded in the non-Asian trial of the First-Line Advanced Gastric Cancer Study study (median OS, 13.0 movs8.6 mo, respectively)[101,102]. Scholars have also found that genetic polymorphisms play an important role in selecting NAT for each patient[103]. Additionally, the Trastuzumab for Gastric Cancer study confirmed that chemotherapy combined with HER-2 targeted therapy resulted in a better therapeutic effect than chemotherapy alone for patients with high HER-2 expression[76], which may enlighten us about the possibility of neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus targeted therapy. The heterogeneity of histopathology in GC also results in different response rates to the same regimen.Although the latest NCCN guidelines of GC (2019.V2) did not recommend the best regimen for each pathological type, clinical trials such as the FLOT study have proposed different histopathological regression rates among different histology types.We should never handle GC as one kind of disease, and preoperative treatment will eventually be recommended based on the histopathology types (Lauren, JGCA, WHO classification,etc.) and/or the molecular types (TCGA, ACRG classification,etc.)[104-108].In the future, the individual differences of patients may be carefully considered before performing NACT, and cytotoxic regimens combined with targeted therapy may be a new option for certain patients[79,81,82,109-111].

Finally, the strategic flow of NAT will be continuously perfected. The booming of NAT in the past decade benefited from abundant high-quality clinical trials, while the decision-making process of NAT still needs to be perfected. For example, there is still no consensus on whether surgery can bring absolute benefits to patients who exhibit an excellent response to NACT. And for patients who have received NACT but did not achieve R0 resection, which treatment (either chemoradiotherapy or alternative chemotherapy) should be administered remains unclear. The clarity of such decisions will have substantial impacts on patients’ prognosis and quality of life. We believe that the NCCN guidelines will continue perfecting the strategic flow to allow better choices for patients base on future studies and trials.

CONCLUSION

NAT is becoming the standard treatment for patients with resectable, nonmetastatic LAGC. Although the universality of present evidence is insufficient, and the frontier of NAT is still led by Western scholars, we are always confident in Asian researchers for their unremitting efforts[112,113]. We are also looking forward to more high-quality studies such as the NCT01534546, NCT02555358, and NCT00252161, which will help to establish a characteristic NAT strategy that is more appropriate for Asian populations.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology的其它文章

- Precision medicine for gastrointestinal cancer: Recent progress and future perspective

- Digestive tract reconstruction options after laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer

- ldentification of candidate biomarkers correlated with pathogenesis of postoperative peritoneal adhesion by using microarray analysis

- Abnormal CD44 activation of hepatocytes with nonalcoholic fatty accumulation in rat hepatocarcinogenesis

- Laparoscopic dissection of the hepatic node: The trans lesser omentum approach

- Multi-institutional retrospective analysis of FOLFlRl in patients with advanced biliary tract cancers