Tonghui River

2020-01-07

The Yu River and the Datong River are actually the same one, which also named the Tonghui River, a section of the Grand Canal of the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), connecting Capital City and the Northern Canal. The Tonghui River was known as Datong River in the Ming Dynasty, while the original Tonghui River flowing in the city of Beijing adopted the alternative name Yuhe River. The Yuhe River refers to the specific section of Tonghui River enclosed in the Imperial City, which is why cargo ships for grain transportation were only allowed to arrive in Tongzhou. Later in the Qing Dynasty, the royal cargo ships for grain transportation were allowed to dock at the Datong Wharf, and the grain would be transferred by barges or carriages to the Chaoyangmen Gate and then distributed to the imperial granaries scattered in Beijing. As the city developed and changed, the Yu River, with most of its watercourses within the Imperial City abandoned, finally transformed into the underground river. The ruins of Yu River, stretching from Houmen Bridge at the east end of Lake Shichahai to Beiheyan Street has reappeared due to two terms of reconstruction projects since 2007. The beautiful scenery with a river flowing through streets and alleys was brought back to the city. The section of Datong River to the east of the Dongbianmen Gate was also unveiled with a new appearance to show extraordinary splendor as a witness of the ancient culture of the Grand Canal.

The Marks of the Grand Canal Left in the Yu River Relics Park

Lake Jishuitan, as a large wharf at the northernmost end of the Grand Canal of the Yuan Dynasty, had faded in history in the early years of the Ming Dynasty. After the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1636-1912) Dynasties, the Lake Jishuitan has changed tremendously with its large size unchanged, but was renamed Lake Shichahai. Furthermore, there is a bridge from the Yuan Dynasty, which never changed its location despite several changes of its appearance and name. Even to this day, it still functions as a bridge and enjoys a good reputation, and that is the Wanning Bridge (Houmen Bridge).

If you do not pay much attention to the stone guardrails and balusters on either side of the bridge, the bridge looks nothing special because it is paved with asphalt and is connected to Dianmen Outer Street, and becomes part of the street, with busy traffic all day long. You may misunderstand that it is just an asphalt-paved road, instead of a bridge. I noticed it before because of its stone guardrails and balusters, the structural elements of the bridge show that this asphalt pavement is also a bridge deck and this bridge is an ancient one with time-honored charm, which is not mainly from the bridge itself, but from the streets connected by the bridge. From south to north, just a few hundred meters away is the Drum Tower. In front of the lofty red Drum Tower, there are numerous modern buildings on both sides of the street, but more than that are stores built in antique style and hutongs interspersed with classic two-story buildings and high-rises. The architectural style and the commercial atmosphere are so attractive that the bridge is easy to be neglected. After the above-ground structure on the east side of the bridge was demolished, the watercourse was excavated. Moreover, the watercourse on the west side of the bridge and the Qianhai (front lake) of Lake Shichahai were cleaned up, and the Jinding Bridge, a three-arch bridge at Qianhai, and the low-rise Wanning Bridge were separated from each other by a short section of river, which presented a typical riverside landscape. After 2004, the Huode Zhenjun Temple on the north bank of the river was completely renovated, the Yu River to the east of the Wanning Bridge was also reproduced. The bridge stood out for its geographic location and topographic feature, and became a scenic spot when viewed from the bank of the Yu River. Standing on the bridge, you can see the Lake Shichahai in the west, catch the sight of the Huode Zhenjun Temple in the northwest, and appreciate the scenery of the beautiful Yu River flowing through the streets and alleys. How enchanting those views are!

The bridge was named Wanning Bridge in the Yuan Dynasty and resumed the name till the end of 2000. It has had so many names before, each of which is with its own meaning. In the Yuan Dynasty, the bridge was commonly known as Haizi Bridge because the water where the Lake Jishuitan was located was called Haizi (lake). After the Ming Dynasty, the bridge was named Dianmen Bridge or Dian Bridge because it was in the north of Dianmen of the Imperial City and opposite to the Dianmen. Dianmen is the back gate of the Imperial City, so the bridge was once called Houmen Bridge (Back Gate Bridge). It was said that the name Wanning Bridge in the Yuan Dynasty implied “Forever Peace, Forever Reign”.

Wanning Bridge is located on the central axis of Beijing nowadays, and according to the historical materials, it was also situated on the central axis of the Imperial City in the Ming and Qing Dynasties and of the Capital City in the Yuan Dynasty. The central axis has a close connection with the meridian, which is terminated by the North Pole and the South Pole, connecting points of equal longitude on the Earths surface. Traditional thinking holds that, for successfully building the city of Beijing, it was a taboo to take the meridian as the central axis; therefore, the central axis was shifted slightly to the east, which has been verified by experts with specific tests. In 1950s, a stone rat and a stone horse were unearthed on the west side of Wanning Bridge and the west side of the moat at the Zhengyangmen Gate, respectively. In ancient times, Chinese people used “the 12 terrestrial branches” to name the hours and the 12 Chinese zodiac animals to tell the time. Coincidentally, if connecting the locations where the stone rat and the stone horse were unearthed, the line exactly matches the central axis of Beijing, at the north end of which lies the Wanning Bridge. The position of the stone rat under the Wanning Bridge built in the Yuan Dynasty is the best piece of evidence for the aforesaid fact.

The stone beasts guarding the river bridge are commonly-used ornaments. A total of six stone carved water-taming beasts, which were unearthed at the Wanning Bridge, are lying prone on the stone berths, with two on the east side and four on the west side of the bridge. One of them is inscribed with the date “September of the Fourth Year of Kublai Khans reign of Yuan Dynasty”, indicating that it is a water-taming beast from the times of Kublai Khan in the Yuan Dynasty, while the other five ones are from the Emperor Yongles reign of the Ming Dynasty. The water-taming beasts on the west side of the bridge are more noticeable due to the larger size and are well protected as a scenic spot by an iron fence, while those on the east side are unnoticeable if you do not pay close attention to. According to a legend, under the Wanning Bridge there was once a water mark, which is an upright stone column inscribed with “Beijing” or “City of Beijing” for plugging up the “eye of the ocean” beneath the city of Beijing. If the water rises to the height of the inscription, Beijing then is under the threat of flooding. However, the water mark has never been discovered throughout the previous repairs since the Ming Dynasty, it is still a legend.

The Wanning Bridge is provided with a floodgate called Haizi Gate in the Yuan Dynasty and renamed Chengqing Gate later, which is the first water channel beside “the ancient seaport of Beijing”. By lifting and dropping the floodgate, the water flow is controllable to make sure the river navigable, which is why the cargo ships for grain transportation in the Yuan Dynasty could get in and out of the Lake Jishuitan smoothly.

Later generations have speculated that the Wanning Bridge was similar to the rainbow-shaped bridge in the painting Riverside Scene at Qingming Festival in the Song Dynasty, or looked like a three-arch stone bridge. According to an illustration in a published book authored by a Japanese during Emperor Jiaqings reign in the Qing Dynasty, the Wanning Bridge had two lateral arches much higher than the ground and a middle arch wide and high. However, the Chinese academia disagrees with the Japanese version. It is hard to figure out the original appearance of the Wanning Bridge in consideration of its function of allowing cargo ships to pass in the Yuan Dynasty. For the tourists nowadays, the Wanning Bridge in history is still a mystery.

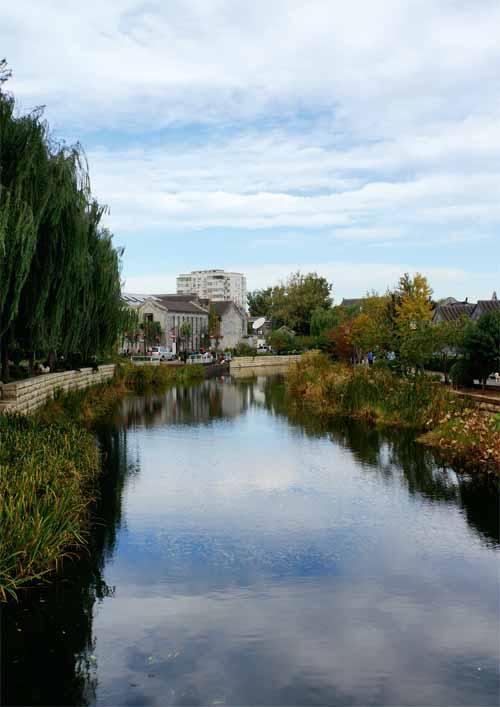

Today, the Wanning Bridge spans over the Yu River, which with stone dikes on both sides. A short section of the Yuhe River on the west side of the bridge is connected with the Qianhai (front lake) of Lake Shichahai, and the Tonghui River Relics Park on the east side of the bridge is commonly known as the Yu River Relics Park, which is separated by the Pingan Avenue into two parts: the North Part of Yu River Relics Park covers the watercourse from the north of the Dongbuya Bridge to the east of the Wanning Bridge and the areas on the both sides of water course from the south end of Dongbuya Hutong to the west end of Maoer Hutong; the South Part of Yu River Relics Park, which does not have an exact name, is opposite to the North Part and has a similar watercourse as that in the North Part. The watercourse of the North Part, with a big river bend, flows under the Wanning Bridge to the east and turns south to the Dongbuya Bridge after passing through a curved bridge; the watercourse of the South Part runs to the south and turns east soon to the west side of Beiheyan Street. The Jixiang Sub-district Office is located on the south side of the river, and the north-south Huangchenggen Relics Park is situated on the other side of the roadway of Beiheyan Street, which is built on the ancient watercourse of the Yu River still buried underground. From the names of streets and hutongs like Beiheyan (north river bank), Shatan (sand beach), and Nanheyan (south river bank), it can be concluded that, during that period, the original Yu River, which converged with the Jinshui River and the Tongzi River, flowed to the south from the Nanyanhe Street and turned east to run into the water area nearby the Datong Wharf and pour into the Datong River after passing through the Datong Gate.

The Yu River Relics Park, which is built on the unearthed ancient watercourse of the Yu River, has its South Part completely enclosed in the ancient Imperial City.

On the east of the North Part of the Yu River Relics Park lies the internationally renowned South Luogu Lane, which is a well-preserved historical and cultural block with a number of former residents of celebrities and an endless stream of tourists all day long. The architectures along the two sides of the watercourse are built in the antique style to reproduce the past scenes of the Ming and Qing Dynasties. In addition to several ancient bridges spanning over the river, there is a wooden curved bridge painted in a color of brownish red. Along the banks of the river, there are waterside pavilions, artificial hills, and lush plants, including willows, gladiolus, flowers, trees, and reeds. When wandering along the river, you may feel like traveling back to the ancient times. On the west side of Fuxiang Hutong and under a marble bridge, the newly replenished water of the Yu River was cut off to expose a wide section of ancient watercourse from the south of the marble bridge to the Dongbuya Bridge. Even though it looks like a big pit, the section of ancient watercourse is full of historical and cultural connotations. It is consisted of the vault face of the Dongbuya Bridge, the approach bridge, the berths of the ancient watercourse, the river bottom paved by bricks, and the approach bridge bases paved by stones, all of which are the historical relics from the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Time has left marks on all of the bricks, tiles, and stones, to deliver a strong sense of vicissitudes. This section of the ancient watercourse in the Yu River Relics Park is a site specially kept as it was before the unearthing of the ancient watercourse of Yu River in 2007. On the east bank of the river, there are the rebuilt Yuhe Nunnery, the unearthed stone tablet, and the Dongbuya Hutong Architectural Complex. A cluster of Beijings old-fashioned residences are strewn at random like guardians defending the river dikes and the approach bridge of the Dongbuya Bridge, thus adding a sense of vicissitudes to the river.

The ancient watercourse in the South Part of the Yu River Relics Park has been also unearthed and replenished with less fresh water than that in the North Part. On the both sides of the river, there are also antique streets, lanes, and quadrangle courtyards in the style of the Ming and Qing Dynasties, exuding the charm of ancient China. Specifically, the sightseeing platform on the south bank is designed with a Grand Canal scenery sculpture wall as long as 116 meters, which consists of five rectangular pieces of different heights and sizes. The sculptures are embedded in the brick wall with the red copper high-relief technique, to demonstrate the scenery along the over-1,700-kilometer Grand Canal starting from Baifu Spring, Dongbianmen Gate, Tonghui River of Beijing to Ancient Tongzhou City and Ancient Tianjin City, and then to Yangzhou, Jinshan Temple, and Zhenjiang. When strolling in the Yu River Relics Park, the tourists may catch a glimpse of the wonderful scenery of the Grand Canal. The Park is a urban water landscape park that brings the ancient Yu River buried underground for decades back to light and reproduces the beautiful scenery with a river flowing through streets and alleys, by demolishing ground buildings over the ancient watercourse, turning over the cover plates and dredging the watercourse.

Datong Wharf at Dongbianmen Gate: A Stop on the Grand Canal

Almost all the Beijinger hear about the Dongbianmen Gate, while few of them could specify its look and location, unless seeing it before it was removed in 1958. Several decades have passed, Dongbianmen Gate now is no more than a name for site, flyover and bus stop.

Getting off at the bus stop of Dongbianmen Gate, you could walk in the Beijing Ming Dynasty City Wall Relics Park from the north side of the stop. The Southeastern Watchtower is near to the east side of the stop. The Park is over one kilometer in length. After two terms of restorations, the remaining wall of the Ming Dynasty is still full of vicissitudes. There are other two parks around the city wall. One locates to the west of the Watchtower, extending to the east of the Chongwenmen crossroad. The other locates to the north of the Watchtower, shaping like an esquadro without great extension on both east-west and south-north directions, with its north side close to the eastern entrance of Beijing Railway Station and in adjacent to the east of the second ring road. The outside area of the remaining city wall was once occupied by dwellings and other buildings and the wall was enveloped by disordered buildings and was hard to see. After the Park was built, the disordered buildings were replaced with lawns, passageways, flowers and trees. More than 200 ancient trees are preserved, most of which are Chinese scholar trees, in addition to gingko, Chinese pine, etc., and more flowers and trees have been planted. In summer, visitors could see lush locust trees, bush and lawn, among which the trees are as dense as forests. As spring comes, kinds of plum blossoms among the trees sprawl in dazzling pink, glaring scarlet and bright yellow. Over 1,000 plum blossoms of more than 40 species form an ocean of flowers, or a colorful river among the tall trees. In autumn, the red and yellow leaves decorate the passionate season as an eye-catching scene. No matter how dense those shrubs or trees are, they cannot hide the magnificence of the old city wall. Surrounded by trees, flowers and grass, it is dilapidated, but indomitable and tenacious, mostly unyielding under the blue sky and the sun.

Why do we introduce the Dongbianmen Gate here? What does it have to do with the Grand Canal? When you walk to the foot of the Watchtower, you will find two artificial marble tablets lying at the corner of the square slightly to the west, one of which inscribed “Flat Peach Palace” and the other “Canal Transport Wharf”. The notes read, “The Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal was built during the reign of Emperor Yang of Sui Dynasty, starting from Yuhang City in the south and ending at Tonghui River in the north. The riverway by the northeast side at the foot of the Watchtower in the inner city is a wharf, also the north end of Tonghui River.” Therefore, here Dongbianmen Gate was once a riverway and a wharf at the north end of Tonghui River as well.

I cannot imagine that it used to be the wharf at the north end of Tonghui River of the Grand Canal!

The word “end” excludes the possibility that the wharf was built in the Yuan Dynasty, for the wharf at that time was in Jishuitan Pond. Thus, the wharf might be built as early as after the Ming Dynasty, since ships transporting grains were not allowed into the city then, and the waterways were of a complicated design after the Ming Dynasty.

At present, the railway lies to the north of the Watchtower, bearing the trains in and out of the Beijing Railway Station. A flyover stands at the southeast of the Watchtower. All flyovers in Beijing are huge, including the one at the Dongbianmen Gate, which is giant and complicated in structure, even incorporating a railway bridge as a part of itself. The east second ring road goes it through, and the East Avenue of Chongwenmen Gate is connected to other roads via the flyover. In addition, it has to cross over the riverway, which takes a turning to the southeast at the east of the Watchtower and then runs southwards. In terms of geographical position, it should be the outer moat of the Ming and Qing Dynasties. However, it doesnt extend northwards, but turns to the floodgate instead and runs eastwards, directly converging into the Tonghui River of Tongzhou. The ancient Tonghui River is just at the foot of the Watchtower!

In the Ming Dynasty, Tonghui River was known as Datong River, a name might originating from the Datong Bridge at Dongbianmen Gate, which marked the junction between the Yu River in the downtown and the Datong River.

Datong Bridge, a three-arch stone bridge outside the Dongbianmen Gate in Ming Dynasty, has arches and sharp-nose piers, which are in favor of water diversion. There are vertical stone grooves on the side walls of the four piers, which could hold wooden screens to block the flow. Datong Bridge serves as both bridge (Datong Bridge) and floodgate (Datong Floodgate). Its also called the First Floodgate, namely the first floodgate along the Tonghui River. Datong Bridge, Datong Floodgate and Datong Wharf were still in existence until the late Qing Dynasty.

The riverway in the downtown around the Dongbianmen Gate has turned into streets and roads, ideal for sightseeing and entertainment. In addition to the Park, people could visit the Watchtower, whose ancient, primitive and distinctive structure would give people entirely new experience. The exhibition gathering historical photos of city gates and towers of old Peking would definitely excite tourists, since the old photos reproduced the disappearing city gates, gate towers and lives under the city wall. The ancient city wall of Ming Dynasty near the Watchtower was completely restored, whose crenellations, to some extent, made up for the loss of the old city wall. People could get a birds eye view of the old Beijing Railway Station there. The ticket of the Watchtower costs only RMB 10 yuan. The quiet and pleasant Park to the north of the Watchtower has magnificent corridor of classical style enveloped by green shade of trees. The riverway along the second ring road is suitable for sightseeing and entertainment. There is also a small park on the sloping bank. Appreciating the Watchtower from the other side of the river, you can feel a special charm. The city is surrounded by clear water and the water reflects its shadow, on which people could feast their eyes. Visitors here may cannot help but think of the history of Dongbianmen Gate, and the bustling scene at Datong Wharf in the era of the Grand Canal. After all, it used to be the terminal of the grain transportation in Ming and Qing Dynasties. In the Ming Dynasty, the grain-transporting ships were forbidden to sail into the inner city, while the barges had to take over the grains and transferred them to the Chaoyangmen Gate along the moat in the Qing Dynasty, where the grains were distributed to each imperial granary. Datong Wharf was also a passenger terminal, where the visitors to the capital along the water route had to disembark. In the Chapter 3 of Cao Xueqins A Dream of Red Mansions “Lin Ruhai Recommends a Tutor to His Brother-in-Law, The Lady Dowager Sends for Her Motherless Grand-Daughter”, the heroine Lin Daiyu went ashore here. The author Cao must have personal experience. In fact, many historical figures had left farewell poems here at Datong Wharf.

I have seen the old photos of Datong Bridge, Datong River and Datong Wharf and found the wide riverway and intensive barges, as well as the city wall, watchtowers and Dongbianmen Gate vivid in mind, which make me feel that everything has gone. The Datong Wharf at the Dongbianmen Gate was now history.

Vogue of Imperial Granary

Its necessary to turn our eyes to the north. Walking along the East Second Ring Road to pass the Chaoyangmen and Dongsishitiao flyovers, and turning southwards to the street corner, you will see several ancient granaries along the wall at the east side, sitting lordly against the surrounding high-rises. Three Chinese characters “Nan Xin Cang” (name of the site), made of thick white marble, are closed to the first granary at the street corner. The sign board nearby tells that the street is full of media companies, galleries, cultural development companies and specialty restaurants. Walking in five to six hundred meters from the entrance, you will be shocked with a group of nearly-encircled granaries. On the east side, the red lanterns hanging from the lampposts standing before the row of granaries. On the south and north wings, granaries facing south or north expand westwards, and countless yards are separated among granaries. Nanxincang Street lies between the ancient granaries and fancy buildings where Fashionable and luxury stores and restaurants locate on the ground floor. Green belts and gardens are built with creative decorations, extending along the street in front of the granaries. Fashion, elegance and tranquility are deeply interwoven with vicissitudes of life and antiquity here, displaying the charm of the coexistence of “new and old, fashion and history”.

There is a statue of Guo Shoujing in the garden, as well a monument standing on the street entitled “Grand Canal-Nanxicang, a major historical and cultural site protected at the national level” set up by the Beijing Municipal Administration of Cultural Heritage.

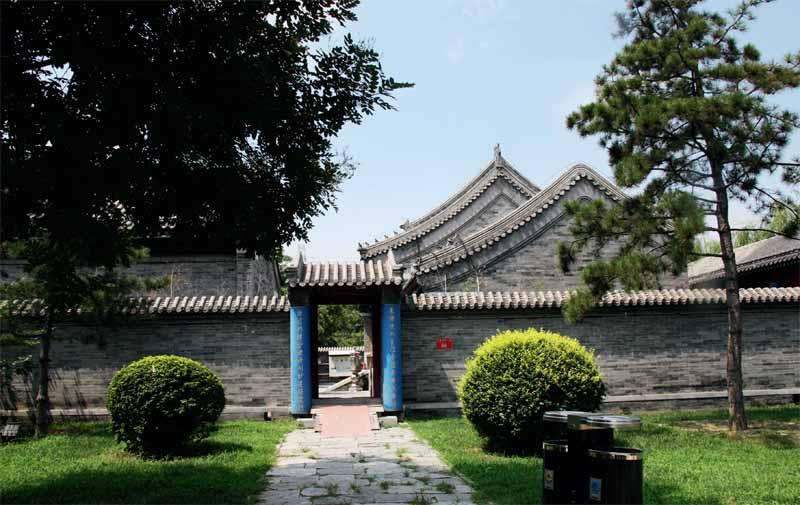

Nanxincang is an official warehouse for grain set up in the inner city of Beijing in Ming and Qing Dynasties, commonly known as Dongmencang. It was initially built in 1409 (the seventh year of Emperor Yongles reign of the Ming Dynasty) as an important part of the Grand Canal scenery and its cultural heritage, which cannot be ignored. Moreover, Nanxincang has become a popular site in Beijing as a historical and cultural heritage and intangible cultural heritage with 600 years of history and attract peoples attention in an irresistible manner, inspiring magnificent fashion ideas beyond imagination.

Many people get to know and come to Nanxincang to appreciate the fashionable and special delicacies, or the outstanding performance in “imperial granary”.

The revised Kunqu opera Peony Pavilion has been performed for hundreds of times here, which must deeply impress the audience. Unlike the shows on stage, here the audience seat where the stage should be, with wide and comfortable seats lining in a higher and higher manner, just like distinguished guests sitting at the center of the ancient hall and among the old wooden pillars of the granary. The actors perform on the wooden floor with the rock on the bottom, where vent holes 30 cm under are set to dehumidify and keep the grain dry. The band, in palace costumes, play against the wall that built by large city wall bricks, whose bottom is as thick as 1.5 meters and top 1 meter without paste. The clerestories are opened at the ceiling to prevent birds invasion and vent the vapor from inside.

Two leading actors perform with lanterns veiled by white gauze as the setting design. Even though you have no idea about the story, the ballad and dialogue will give clear explanations, no matter you understand or not. Created by Tang Xianzu, a playwright of the Ming Dynasty, the opera is about a classical romance, in which Du Liniang, the heroine, resurrected to marry Liu Mengmei, the hero. Kunqu opera originated from the Kunshan style prevailing at the wharfs of Suzhou in the 14th century, boasting elegant and beautiful language style. After over 600 years, its still prevailing so far, crowned as “ancestor of Chinese operas”. Its mild and melodious in tune and exquisite in performing like bubbling water. In the space of “imperial granary”, which is 7.5 meters in height, 23.3 meters in length and 17.6 meters in width, the performance, characterized by dancing dress and long sleeves, demonstrates both elegance and antiquity that is beyond words, leading the audience to appreciate the cultural treasure beyond time and space.

Nanxincang was built on the previous foundation of Taiping warehouse in the Yuan Dynasty, when the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal was built to solve the problem of grain transportation from the south to the north. Most granaries then were close to the east of the capital, for the moat nearby could facilitate the shipping and loading. Another reason lies in the requirements of building granary, including altitude, ventilation, sunlight and waterproofness, all of which have to prevent the grain from mildew due to dampness. During the Emperor Yongles reign of the Ming Dynasty, Beijing had developed into an extremely prosperous city, and the transportation of grain from the south to the north emerged as the priority. Officials of the Ministry of Revenue proposed to dredge the river channels of the Yuan Dynasty and carry out water transportation. Emperor Yongle attached great importance to this, so mobilized 300,000 migrant workers to dredge the channel of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal in the Yuan Dynasty and built many granaries in Tongzhou and Beijing. All the seven official granaries in the capital gathered near the Chaoyangmen Gate (known as “grain transportation gate”). Nanxincang was the most important one of the seven official granaries, with 180 warehouses in total. In the Qing Dynasty, the capital granaries were rebuilt on the basis of the old ones of Yuan and Ming Dynasties. During the Emperor Qianlongs reign of Qing Dynasty, the number of capital granaries increased to 13, with more advanced technology of grain preservation compared with that of the Ming Dynasty.

Granary has a long history in China. There are three kinds of granaries in the past, namely “Yi Cang” (private granary for peasants), “Chang Ping Cang” (granary for the official departments) and “Guan Cang”, the official granary providing provisions to the imperial family, civil and military officials and the troop, also known as the “imperial granary”. Nanxincang is one of the top imperial granaries in Beijing in terms of size and preservation. However, numerous huge granaries have faded in history.

Datong River:Modern Charm of the Ancient Water

To the south of the Gaobeidian subway station and bus stop stands a stone bridge. The reservoir on the east of the bridge flows at an astonishing speed while the water on the west is as calm as a lake, against whose wide surface, dwarfing the modern skyscrapers and antique buildings on the south and north sides; as for its length, it is even impossible to find the end when looking to the west. This turns out to be the Tonghui River. It is quite unexpected that it still covers such a vast area nowadays.

Tonghui River is a river with floodgates. Though Guo Shoujing is not the first one to build floodgates in order to promote grain transportation, it is obvious that he knows better the advantages of floodgates than anyone. There are two branch canals from Beijing to Tongzhou: the northern branch is Ba River, also known as Futong River, originating from the northern part of Lake Jishuitan, flowing out of the Guangxi Gate of the Capital City along the Forbidden Citys northern moat and running through the northeast suburb to empty into the Wenyu River. Seven dams are built across the river, to make it possible for cargo ships to go level by level to the upper reaches. When the tribute grain passes the easternmost Shengou Dam, it is transported to the next dam upstream by ships and then carried by coachmen to the boatmen waiting in front of the next—this is called “segmented lightering”, the only solution to the water scarcity for grain transportation. The southern branch canal from Lake Jishuitan to Tongzhong is Tonghui River, a watercourse enabling cargo ships bearing grains to directly reach Lake Jishuitan in the Capital City. It also has floodgates spanning over. The watercourse which originates from Lake Jishuitan, runs to the east and then to the south, passes Nanshuimen (South Water Gate) and reaches the old Grain Canal, a floodgate is built every 10 li (5 kilometers) and there are seven locks in total all the way to Tongzhong, with intervals about one li (0.5 kilometer) between every two floodgates. The achievements of Tonghui River lie not only in bringing new water sources, but also in solving the two major challenges in building the canal in Beijing, namely water scarcity and the steep slope. The terrain of Beijing is high in the west and low in the east with a steep slope and a high water flow rate, in which case, controlling the flow by floodgates, selecting the best route of canal and keeping the course as short as possible are all effective measures.

The floodgates separate the river into two reaches. When ships pass, the flow of water will be obstructed.

The number of floodgates across the Tonghui River underwent changes during the Ming and Qing Dynasties. It stopped serving as a reach for grain transportation in the 27th year in the Emperor Guangxus reign in the Qing Dynasty, that was, the year of 1901.

Gaobeidian is an old wharf, with three Pingjin Floodgates (the upper, the middle and the lower) to its east, which are positioned 8 li (4 kilometers) away from floodgates of Datong Wharf.

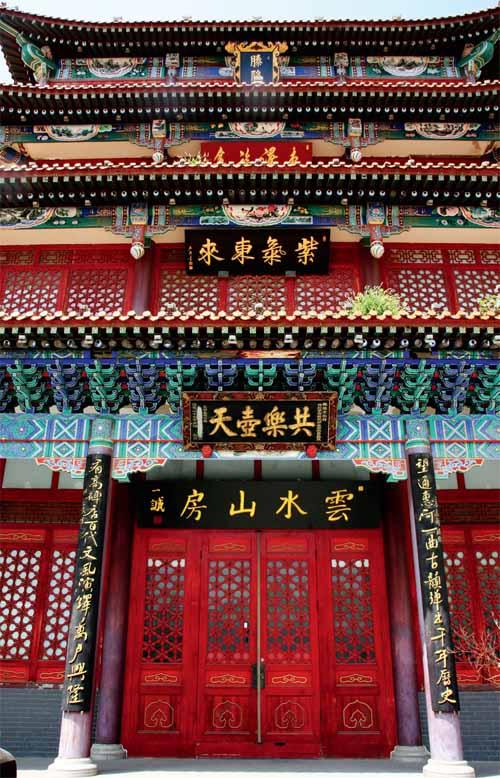

Having been cleared and dredged, the Tonghui River flows tranquilly by the Gaobeidian Village. When appreciating its serene beauty, you can lean upon the stone guardrail along the river bank, and it also serves as a spectacle, injecting a modern vigor into the ancient river. Too many buildings or skyscrapers nearby might be out of tune with the charm of the ancient river, thus all the buildings in Gaobeidian Village are designed in an antique manner—no matter how many storeys there are, the roof of buildings always feature a classical style and the shops on the ground floor are all decorated with classical elements. This might be a reflection of the glorious canal culture in Gaobeidian. Another evidence is the padauk museum on the north bank of the river—as majestic as a palace, it echoes the antique residences and commercial buildings in Gaobeidian from the other side. The southeast bank reaches out to the watercourse to form a gentle sandy slope. The green grass at the foot of the slope and the tall willows along the bank together present a scenery brimming with wild beauty, reminding people of the wilderness and the natural river banks there, which is both comforting and touching.

The southeast and southern banks have been turned into parks by Gaobeidian Village. The southeast part serves as a park with scenery. Towering ornamental stones, bushes and bamboos add a natural charm to the park. Going along the highway, you will find the Tenglong Tower which is on a par with the “Four Famous Towers in China” in its imposing presence with yellow-glazed-tile roof and four eaves. Squares border the Tower on the west and the north, where pavilions of classical style stand by the river, with semicircle-tile hip-and-gable roof, red pillars, three-step stone foundation and newly-renovated ancient temples. It is not clear if the General Temple by the water and the Dragon Temple near Huinan Street are reconstructed or newly-built, but they are sure to overwhelm everyone with their typical and classical details everywhere. Between the two temples lies the Filial Piety Garden, in which stones carved with the traditional twenty-four stories about filial piety are placed among leafy trees along the flagstone path and on both sides of the square in front of the temple. Ancient willows wave by the riverside, displaying their experience during hundreds of years with their thick trunks—they are the witnesses of the prosperous time of the old Tonghui River, along with the square bollards and the stone archway and statue of Guo Shoujing in the park.

Offering a feast for eyes, the village park is a good place for entertainment. When the Spring Festival comes, folk ceremonies and events will be held here, such as the grain transportation temple fair and folk-dance performance featuring sedan chairs as props, unveiling a unique charm. It is definitely worthwhile to come here for the ancient canal culture.

Being several kilometers to the south is the street of Ming-and Qing-style furniture. Towers are erected in the corner, and the antique shops along the long street with ancient buildings together will bring you back to history.

The reach of Bali Bridge is a part of Tonghui River which flows near Gaobeidian and presents a wild and natural view. The Yongtong Bridge, commonly known as Bali Bridge (for it is 8 li [4 kilometers] away from the West Gate of Tongzhou), which spans over the watercourse of the ancient canal system, maintains its splendor even to today. Initially constructed in the 11th year of Emperor Zhengtongs reign of the Ming Dynasty (1446), it is still as elegant as before, never letting the time and tide sweep away its grace. Taking a look on the bridge, you will see the broad river course stretching between the lines of trees, providing a close and comforting encounter with the nature even in winter when withered trees, wilted grass and freezing weather shroud the forest of high rises and subways of modern city. The ancient bridge is paved with asphalt for traffic, but this will not get in the way of admiring the scenery. Stone guardrails extend for 50 meters from south to north, with 32 pairs of baluster columns set in between. Stone lions stare at each other in various looks on the top and four beasts lie on each side of the columns with their chest and head high in a majestic air. The bridge is built with three arches, a tall one in the center and two lower ones on either side. A stone dividing the water can be found behind the center arch and statues of beast full of scales and with long tails are positioned on both sides to keep the floods down—they are lying there, tilting their heads to glare at the river.

The Bali Bridge is famous for its attractive view “Long Bridge Mirroring the Moon”, an implication that the best scenery is offered at night in the bright moonlight.

As time goes by, the river course under Bali Bridge is no longer used for transportation, which makes it hardly possible to appreciate the beauty of “Long Bridge Mirroring the Moon” in the river, while there is still chance to enjoy the outstanding scene of “Long Bridge Lifting the Sun” as long as you come at the right time and stand at the right site. I once caught sight of this spectacular view, watching the red sun hanging above the bridge at dusk.

The Bali Bridge is also a bridge of heroes, witnessing the history of fighting against the Anglo-French Allied Forces in 1860.