树商陆:潮湿的潘帕斯大草原景观的实践与表达

2019-11-30乌拉圭安纳瓦拉里诺卡赞斯坦梁艺馨钱丽源

著:(乌拉圭)安纳·瓦拉里诺·卡赞斯坦 译:梁艺馨 校:钱丽源

1 介绍

在乌拉圭,树商陆是植物Phytolacca dioica的通用名。OMBÚes指高校科研项目“树商陆与自然相关的价值”的研究目的和研究方法,项目名称清晰地阐述了本项目的研究、教学和推广目的。该项目的名称OMBÚes是一组字母OMBÚ与es的组合,其组成的单词可有多种理解含义(在西班牙语中是有效的)。其遵循了诗的格式,即在同一个单词中结合大写和小写的写法。因此,能同时理解为单数或复数,以突出在不同数量层面(对孤立个体和树商陆群的兴趣)上和在定性层面(对普遍物种或对特定个体相关价值的研究)上的二元性分析。一组关系也能通过包含动词“ser”①的现在时态来强调其意义,并以此为基础对本质属性的暗示:“树商陆是”“自然是”“人类是”……此项目旨在提高人们对景观、当地历史与自然因素相互作用的价值认识,特别是与树商陆相关的实践和表达。由此加强了乌拉圭的领土和文化一体化。

从景观视角出发,随之展开对此项目研究对象树商陆的自然特性的跨学科研究。人类学、社会学和自然科学通过艺术联系起来,其间涵盖了不同的学科,如建筑学、计算机工程学、测绘学、社会学、人类学、民族植物学、历史、美术(造型艺术、绘画、文学、音乐、戏剧)、地图学、地理学、教学法和教育学、研究方法论、人类生态学。

树商陆也被视为教学和推广活动的工具。在此领域中,树商陆会特别地将实践与知识相关联,形成普遍的表达形式,成为将灵感整合成一体的工具。其与教育、社会平等、社区归属感相关联,发挥其价值作用。

树商陆是潮湿的潘帕斯草原的本土物种。此科研工作以树商陆为研究线索,清晰地表达了此树种的特性和可塑性(例如它的尺寸、粗壮轮廓、弯曲构造、药用价值、长寿、凉爽树荫、对强风的抵抗力)。这证明了树商陆是潘帕斯草原上物种的象征,在乌拉圭国家层面和文化遗产中具有重要意义。

2 地理环境

拉潘帕是南美洲的一个地理区域,在那里大型草原经常受到被称为“冷风”的强烈西南风的冲击。潮湿的潘帕斯大草原面积600.00m2,位于乌拉圭、阿根廷东北部和巴西南部交界处。除了在拉普拉塔和巴拉那河周围起伏的潘帕斯大草原外,拉潘帕基本上由生长着低草地的广阔平原组成②。树商陆是这个地区的象征性物种,随着人类的出现,其分布区域随之扩展。西班牙人在17世纪引入的牲畜喜欢的柔软牧草,取代了天然的硬草牧场。

乌拉圭东岸共和国是一个面积约187.00km2的国家,位于南纬30°~35°之间,西经53°~58°之间(图1)。

该国的原始植被属于天然草原,草甸在森林中占优势。目前,这片区域被大面积的畜牧区、农耕区,以及外来引入植物松树和桉树生产林替代。原生森林占不到5%的国土面积。

乌拉圭的本地居民人口约为330万,一半的人口都在首都蒙得维的亚。

乌拉圭人具有包容与温暖的特质,使这片土地在区域层级的地理、生态和人类表达上独具细微的差别[1]。“成为乌拉圭人”意味着文化的融合。这不仅是感受和思想的大熔炉,更是多样异域特质扎根当地特色的咬合器。

3 项目背景

该项目《树商陆与自然相关的价值》始于2013年,与共和国大学(Udelar)③的建筑设计和城市规划系(FADU)合作。FADU中的通信服务、计算机支持服务和视觉传达设计的相关学科也给予技术支撑。东部大学中心(CURE Udelar)的景观设计专业(ldp)、农学院的植物学实验室(fagro Udelar)、工程学院(fing Udelar)的计算机专业 (INCO)和计算机工程专业的学生和教师都参与了此项目④。

项目植入到FADU的设计研究所(idD)的研究计划中,并在该计划中起协调作用,促动不同工作分支间的互动。在2014—2015年间,该项目获得FADU校内扩展项目的资金支撑。在2016年,它又得到了文化教育局附属的费加里博物馆的支持,进行了展览,并出版图书目录集。2017年,此项目又从FADU的校内综合培训部门获得了资金支撑。

1 乌拉圭潮湿的潘帕斯大草原The Uruguayan humid pampas

2 树商陆林,罗沙,乌拉圭,2012Ombu grove,Rocha,Uruguay,2012

该项目入选科技周(SEMANACYT)⑤的年度征集,从而获得了2016年和2017年文化教育局的支助。2013年和2014年的科技周(SEMANACYT)开始与学校开展活动,校园研讨会的诞生为OMBÚes项目的扩展活动奠定了基础。

4 理论框架

笔者开始把景观看作是连接自然与实践和人类表达的桥梁。后来认为大自然是一种文化观念。景观便成为社会与自然间的中介[2]。景观的社会表达建立在物质、神话和自然象征的基础上[3]。我也认为,自然的,真实的和有代表性的,是社会认同的基本因素,是人类栖息地的构成条件[4]。

自然是集体建设的成果。一般来说,植被尤其是树木是大自然理想的代表,因为它具有唤起感知的能力。其复杂的生理特征产生了隐喻或象征性的类比[5]。树木特征会影响对其感知方式、表现形式以及如何使其在景观中得到重视和应用。这就是自然界的创造性与创造的自然界之间的关系[6]。

此外,鉴于树木标本的年龄普遍大于人类,与树木有关的价值包括集体记忆、社会想象力和民族特性。这是由沙玛(Schama)关于英国格林伍德、立陶宛—波兰普斯塔和塞米蒂国家森林[7]的关系所证实的。通过这些意义,可以分析自然与人类之间的复杂关系(属于和不相关的双重状态)。

这些工作是在复杂的模式中形成的。基于3个基本原则:对话(在较高的层级中克服对立)、重现(影响每个人文现象的循环和循环效应)和全息(整体处于部分中,部分组成整体)[8]。这些原则使OMBÚes项目的方法论从理论方面联系起来。他们还支持将树商陆的品质归纳为景观价值。这些价值体现在潮湿的潘帕斯大草原上相关的实践、知识和表达中,包括文学、绘画、摄影和音乐作品,还包括社交、景观、城市和建筑实践。他们也偏爱神话传说,传奇人物与物种、古树个体、树商陆树群有关的奇闻轶事。

5 方法和方法论

大前提是概念适用于方法论,并遵循协作工作的策略。一系列面对面的活动将学校研讨会、高校教学活动、与当地参与者的交流、博物馆展览与ICT(门户网站http://www.ombues.edu.uy)联系起来。大学的科研、教育和推广是明确的,以莫林(Morin)学者的说法,都是相互间的目的和手段,有助于知识的创造。对于莫林而言,知识涉及的循环过程是从分离间的分析,到综合或复杂化[9]。

在组织获取信息的过程中,图示化表达是一个重要的过程。该过程由门户网站[10](http://www.ombues.edu.uy)共同构建并共享。OMBÚes项目的代表性案例和相关实践被绘制下来。制图被视为地域化社会进程的一部分。它是技术和符号运作的产物。通过这种运作,人类社会赋予空间以重要的意义和身份,标榜它们并赋予意义[11]。协作性工作为我们的景观遗产创造出社区感、环境意识和集体责任感。

6 树商陆和潘帕斯大草原景观

地球上每个地区自身都有一个显著的特点:巴西的烈日;秘鲁的银矿,蒙得维的亚的山丘;布宜诺斯艾利斯美丽的帕特里亚;潘帕斯大草原的树商陆⑥

—路易斯·洛伦佐·多明格斯(Luis Lorenzo Domínguez)“树商陆”(1837 年)。

商陆属(来自希腊语,无毒,植物的和紫胶,漆)包含35个种。具体的种加词dioica表明了树商陆的基本特征之一。这个词意味着花朵是中性的,在不同的个体中,他们被定位为雄性或雌性化。虽然花朵和果实并不突出,这一物种的雌雄异株的特征使其在日常的鉴定中出现了一些混淆。即使是19世纪的佩雷斯·卡斯特拉诺(Pérez Castellano)⑦,一开始也认为它们是两种不同的物种[12]。因为只有雌性的才会产生果实,结果只有雌性树商陆可以在个体周围自发结出果实。一般来说,在潘帕斯大草原,树商陆是纯林种植的,凸显了它在无限风景中的轮廓。在乌拉圭,还发现树商陆在Lavalleja和Rocha的一些地方形成森林(图2),偶尔也会沿着河岸成林分布。

树商陆进化出树状株型和圆形树梢,其直径和高度界于10~14m之间[13]。它独特的厚实树干,可以达到7m的直径。主干分生出几个支干。然后这些支干派生出一个复杂而强大的根系系统。它的根系十分突出,当树商陆枝干独立生长时,根与枝干基部更难以辨清。

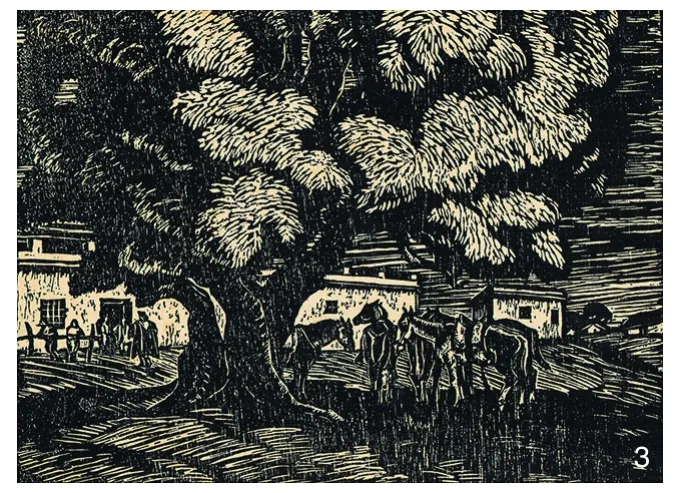

3 吉列尔莫·罗德里格斯的《商店和树商陆》(1937)版刻Pulpería y ombú by Guillermo Rodríguez (1937)xilography

4 老锡店,卡多纳,乌拉圭(2015年)Pulpería de la Lata Vieja,Cardona,Uruguay (2015)

对商陆属植物进行植物分类很困难。一般来说,植物分类为乔木、灌木和草本,需要考虑的因素有:植物生长周期、具体尺寸、组织的一致性(木本或草本)以及生长习性。树商陆结合了不同植物类别的特征。它一方面具有乔木的尺度,另一方面又具有灌木丛的独特分枝系统。而且其也具有仅限于木本植物乔木或灌木的多年生的和寿命长的特征。除此之外,其某些特征也与草本一致。由于这些特殊性,有些人认为它是乔木,有人则认为是灌木,另一些则认为是草本。继Atilio Lombardo教授之后,在本文中,我们优先考虑了树商陆的繁茂程度及其寿命,并将其视为乔木[14]。

树商陆植物器官的化学成分含有槲皮素、奥布丁、精油、过氧化物、植物素、皂素、蔗糖[15],都可以被有效地利用,比如药用以及诱发毒性。

树商陆在基础资料方面的缺乏,会引起大众对其的恐惧和敬畏,由此产生了充满神秘感的神话和轶事。有些故事提到了树商陆的毒性,但实际上只集中在其树皮和根部。除此之外,因为它能用来生产肥皂[12],大众对它是喜爱的。它多用来制作成具有泻药性质的茶叶,为未婚女性拒绝骚扰者时使用。

语言和地区的不同,树商陆也有许多通用名。很多时候,这也证实或补充了学名表达的特征性。在西班牙语中,它被称为“ombú”(在乌拉圭和阿根廷),“rey de la pampa”(在阿根廷)和“bella sombra”(在西班牙和澳大利亚)。在乌拉圭和阿根廷,“lajau”与美洲印第安语Charrúa相对应。在瓜拉尼它被称为“ümboü”(乌拉圭,阿根廷);在图皮,被称为“caruru-guassú”(巴西)和“umbu”(瓜拉尼、厄瓜多尔、巴拉圭、墨西哥、智利和澳大利亚)。法语叫作“Bélombra”;“Raisinierdioïque”(法国)。

上文已经提到树商陆是潮湿的潘帕斯大草原的本地物种⑧[15]。这种植物的出现先于这片土地的文明世界进程,这便是树商陆成为研究核心的决定性因素。然后两者一起演变。它伴随着我们在农村和城市层面的生产,社会发展和文化进程。树商陆在这个国家建立的残酷竞争中生存下来。经历了从大庄园和小牧场,到牧人⑨的游牧生活和适合城市发展的“久坐”生活。这解释了树商陆和taperas⑩,以及树商陆和 pulperías⑪之间的关系。今天仍然有据可考。有些作品已被神化,例如由吉列尔莫·罗德格雷兹(Guillermo Rodríguez)制作的木刻“Pulpería y ombú”(图3)。有些仍然矗立着,如卡多纳的拉塔维亚的杂货店,在杂货店的回收建筑旁边仍然有一棵树商陆(图4)。然而更多的只有历史记载。

许多传统养牛的牧场,其命名暗指树商陆(因为牧场中的主要建筑旁大多有这种植物)。当市里出现这种植物时,也会对地名产生影响。例如 Ombúes de Lavalle市或 Ombúes de Oribe镇名字的由来(图5)。

树商陆的草本特性意味着其枝干无法用作柴火来烹饪食物(冲积平原文化)。因此树商陆无须被砍伐做柴火,这样造就了其广阔的树冠提供凉爽的树荫。这成为Juceca写作故事“树荫”的核心⑫。在他笔下的乡村世界里,有一种荒谬的幽默感,故事讲的是一个人只愿卖给另一个人一棵树商陆的影子,却不卖这棵树。

树商陆为人类提供庇护所,阻挡了来自烈日和南美草原大飓风的伤害。同时,树商陆也受益于人类,它从家庭生活产生的有机废物中获得养料。树商陆的长寿使得树的生命周期比陪伴它们的人类还长。而且建在这种树附近的建筑,其寿命也不如树长。

它的这些特征激发了人类的想象力,为人们提供了民间传说以及各种艺术表现形式。虽然如今的树商陆在世界各地的温带和亚热带地区都是以观赏树的方式栽培的,但这些神话和表现形式都是本土化的。 有一种观念认为,受树商陆保护的房屋最终以废墟而告终;人们惧怕在镜子下打个盹会导致疯狂,或者迷信晚上镜子会照射出白色的光芒。这些想法由哈德逊(W.H.Hudson)⑬于20世纪初发表在他的著作中[16]。

Horacio Quiroga⑭的精彩故事中,Ellobizón(1906)将夜晚的黑暗与沉默,以及来自乡村的咆哮所带来的恐惧混合在一起。树商陆也是家中的狗与未知入侵者斗争的地点。

树商陆与它所象征的景观—潘帕斯大草原有关。这反映在L.L.Domínguez⑮结合复杂多样的历史背景所创作的诗中。

在17世纪,西班牙国王批准阿里亚斯·维德拉(Hernando Arias de Saavedra)将牛和马引入乌拉圭河以东的领土。从而改变了该国的环境和经济平衡。

在18世纪,乌拉圭和阿根廷开始谋求自身发展。1825年,乌拉圭独立于西班牙、葡萄牙、巴西和英国,成为一个独立的国家。1728块土地被允许以“苏厄斯特·德·埃斯特西阿斯”(Suertes de Estancias)的方式迅速扩大。几乎在整个19世纪,战争持续影响着这个国家。在19世纪上半叶,乌拉圭在社会舆论上非常重视这场战争,并且明确表达了态度。在高乔人统治时期,主流的思想认为这是“野蛮的文化”[17]。一个与之有关的文献,何塞·埃尔南德斯(José Hernández)⑯的《马丁·菲罗》(1872年)是高乔流派的典型代表,其中有关于树商陆的记载,“……在经历了这么多的痛苦/危险的焦虑之后,我们到达了撒路—看到了一座山脉,我们的土地—树商陆生长的地方……”⑰。

在19世纪末田野被围合了起来,彻底改变了农村的社会面貌:高乔人被工薪劳工所取代。在1860—1920年间,历史学家巴兰提出了一种新的感性说法,即“文明文化”。在这种新的感性说法中,冲动受到压制,工作、谦虚和死亡的尊严被神圣化[18]。可以认为,乌拉圭开始其社会,政治和经济的现代化。城市生活蓬勃发展,蒙得维的亚市很明显地与周边的自然环境区分开来。

在我们正在研究的130多位作者(画家、作家、音乐家、摄影师、植物学家)中,近一半的作者出生于19世纪,其他人出生在20世纪。他们平均分布在乌拉圭人和阿根廷人之间⑱,极少部分人具有欧洲血统。他们对树商陆的认知源于不同的职业背景。一些是科学家,其他如实用主义者和更具有艺术性的职业人。在后者中,艺术从业者对树商陆的认知从描述性的到象征性的,赞扬其与空间的相关性、与高乔人品质和民族观的相关性,以及其与潘帕斯草原景观、历史线的关联的价值:无限、孤独、暴力、自由、力量、个性和田园诗性。

苏佩维埃尔(Jules Supervielle)⑲将树商陆作为诗歌的主角(Dans la pampa,1919年),并在他的作品Boireàla source(1950年)中提到它,受到了关注。

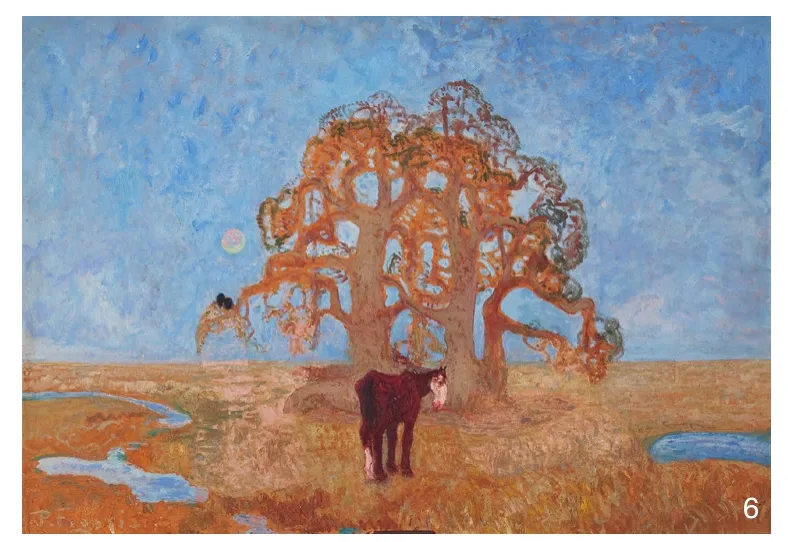

树商陆是佩德罗·费加里(Pedro Figari)⑳作品中的主旋律。这是他绘画作品En la pampa中的主角(图6),也是他绘画和故事中的必备参考。鉴于2类树结构间的相似性,他将它命名为“我们的猴面包树”㉑。

5 杰纳勒尔织部庄园的主要牧场的建筑遗存,树商陆织部,乌拉圭(2015年)Remains of the constructions of the main ranch of the General Oribe estate,Ombúes de Oribe,Uruguay (2015)

在他的故事“男孩子”中,莫罗索利(Morosoli)㉒是一个离开村镇前往首都生活的角色。主角一开始生活的地方宁静而令人放松,有清澈的溪水和一棵树商陆,对他来说,就像一座房子那样大。在成为首都的移民后他失去了田园诗般的田园生活:“刚才他意识到其他人是对的。我一直工作。总是这样。对于生活的意义他什么也没有感受到。没有生活乐趣地活着。”

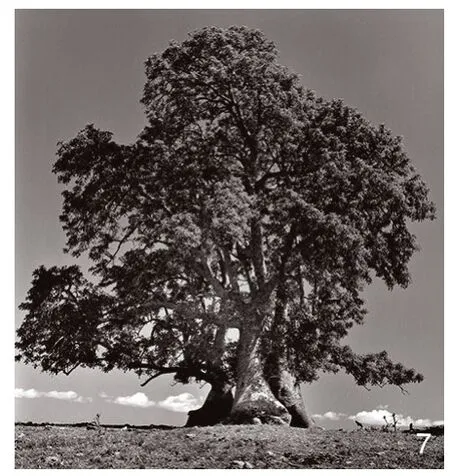

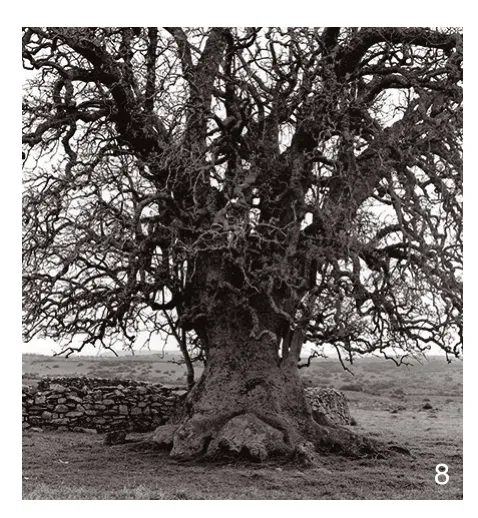

现在约瑟夫里索(José Risso)㉓将他的一部分工作专注于拍摄农村地区的树商陆。 他用黑白相片做类比处理,赞美树的个性,树商陆的神秘感及其植入后的风景效果(图7、8)。

树商陆也和音乐流派有关联。克拉夫德尔(Clave del aire)是加德尔(Gardel)于1930年在巴黎演绎的一首探戈,其歌词㉔由弗尔南·席尔瓦·巴尔德斯(Fernán Silva Valdés)㉕撰写。这首歌关于爱的背叛,关于孤独和痛苦。呼吁各种族间共有的品质(孤独、地域根源、避难所、力量),呼吁解密拉普拉塔典型舞蹈的悲剧精髓的奇闻轶事。

树商陆也是这座城市人们最熟悉的原生树之一[19]。这不仅归因于其与物种相关的大众认知,更归因于其杰出的示范作用。例如,在蒙得维的亚,西班牙大道的树商陆(图9)是该市最着名的树木之一[20]。这棵现存古树在1912年已经是成年大树了,由于当时的蒙得维的亚市长Ramón Benzano的介入,道路布局被重新规划以保留这棵古树。

米格莱特河沿岸和里约热内卢拉普拉塔沿海地带也有一些树商陆。后者相当于海岸船只的灯塔角色。如Ombúde La Mulata,关于它有一个都市传说㉖,邻域的地名由此而来。与乌拉圭各种各样的表演,传说和轶事形成鲜明对比的是,时至今日,树商陆的种植才得以普及。现有的大部分树苗是自发繁殖。然而,由于迷信,它们一般都没有被移植出来。

7 结论和前景

“尽管我们将自然和感知分为两个不同的领域,他们实际上是不可分离的。先于其他感官感受,景观首先是精神的杰作。它的本质是从阶层,记忆和岩石中建立起来的。[7]”这个项目的初衷是理解西蒙·沙玛(Simon Schama)在本文标题中所提到的复杂性。研究的跨学科性可以阐明实践和表达、理论知识和真实空间。此工作的合作性质使我们能够共同建设和珍视我们的遗产,打破条框和领土的边界,简而言之,就是加强我们的身份认同感。在科学文化的普及与民间文化的智慧间的连续往返,使知识能够跨学科地构建起来。这是一个开放性的项目,其中仍有许多工作要做。在这里,知识是一体化的工具,是集体意识的一部分,是多样性的空间。

注释:

① 在西班牙语中,动词“to be”被分解为两个动词“ser”和“estar”。

② “Pampa”来源于克丘亚语,意思是“平坦的表面”。

③ 在乌拉圭,共和国大学是最重要的高等教育和研究机构。它还开展活动,目的是传播文化,并为知识提供具有社会价值的用途。“这是一个由教师,学生和毕业生自主共同管理的公共机构”;引自http://www.universidad.edu.uy。

④ 参与者:共和国大学建筑,设计和城市规划学院:哲学博士学位,安娜·瓦拉里诺(Ana Vallarino,主管、首席研究员);建筑学学士,劳拉·皮罗科(Laura Pirrocco);学士,莱安德罗·雷蒙迪(Leandro Reimundi);建筑学专业,克劳蒂亚·科斯塔(Claudia Costa);学士,桑提亚格·芬特(Santiago Ventós,助理)/农学硕士,建筑学,莱蒂西亚·德拉维加(Leticia de la Vega)(分机号2014—2015);娜塔莉亚·坎波斯(Natalia Campos)(助理,2015年);法比安娜·奥蒂萨(Fabiana Oteiza)(助理,2014年)/农学硕士巴勃罗·罗斯(Pablo Ross,植物学咨询专家 自民党 种族公民平等联盟)/加布里埃拉·斯波罗尼(Gabriela Speroni);(植物学咨询专家 费格罗)/辛西娅·奥尔金(Cynthia Olguin)(视觉传达设计FADU,乌德拉,2014—2015);尼古拉斯·托雷斯(Nicolás Torres,电脑开发人员FADU,乌德拉,2014—2015 )/国际镍业公司:硕士.拉奎尔·索萨(Raquel Sosa,主管工程学生);工程系学生:弗吉尼亚·耶米尼(Virginia Yemini)和玛蒂娜·塞尼瑞斯(Martina Señoris,应用程序设计师);莱昂纳多·维达尔(Leonardo Vidal,2014)/LDCV:博士,塞巴斯蒂安·苏亚雷斯(Sebastián Suárez)和达里奥·因弗尼齐/塑料艺术家费尔南多·斯蒂文纳齐(Fernando Stevenazzi,2016—2017)。

⑤“每年的五月份,我们都会通过各种适合各类公众的活动来庆祝乌拉圭发展起来的科学和技术,以激发人们对知识的热爱和后代的使命感”,引自http://www.semanacyt.org.uy/。

⑥ 地球上的每个地区/它有一个突出的特点:/巴西的烈日;/秘鲁的银矿,/蒙得维的亚的山丘;/布宜诺斯艾利斯-美丽的家园/伟大的潘帕斯大草原;/草原上有树商陆。

⑦(1743—1815)蒙得维的亚,牧师,政治家,农民,那个时代伟大的自学成才的学者。

⑧严格意义上说不是这样的:隆巴多澄清它不是起源于乌拉圭,而是说我们的国家只覆盖它的分散区域(隆巴多,1969年)。

⑨ 潘帕斯特有的居民,熟练的骑手,过着简朴的生活,他们的生活与牛联系在一起,食用牛肉和使用皮革。

⑩ 残破荒芜的牧场。

⑪出售日常用品的商店,主要是食用的。

⑫胡里奥·凯撒·卡斯特罗(1928—2003):乌拉圭人,作家、演员和剧作家。

⑬(1841—1922)自然主义者和阿根廷出身的英国作家。他曾在乌拉圭生活过一段时间(当时是东岸地区),在他的作品中巧妙地体现了当时的乡下和战争气氛以及高乔人的特质。

⑭(1878—1937)乌拉圭说书人、剧作家和诗人。

⑮路易斯·洛伦佐·多米尼格斯(1819—1898),阿根廷诗人、记者和政治家。

⑯(1834—1886)军事记者、诗人和阿根廷政治家。

⑰“在经历了这么多的痛苦和危险的焦虑之后,我们平安地到达,看到一座小山并最终踏上了树商陆生长的土地”。

⑱对巴西作者的研究尚未进行深入研究。

⑲(1884—1960)弗朗哥( Franco)—乌拉圭诗人兼作家。

⑳(1861—1938)著名的乌拉圭画家,律师,政治家和作家。

㉑Baobad被安东尼·德·圣埃克苏佩里在“小王子”(1943年)中永生不朽。

㉒乌拉圭作家胡安·约瑟夫·莫罗索利(Juan José Morosoli,1899—1957)。

㉓摄影师,于1970年出生于乌拉圭的马尔多纳多。

㉔“就像空气中的康乃馨花香一样,她是如此,就像花朵一样/在我的心里。/···在这个地区,/就像树商陆/独处而不开花/我也是这样的;在痛苦中煎熬/我生活的那些年里,/就像这个地区的树商陆/···”。像空中的香气一样,/她是如此/就像花一样/在我心中。//[在这个地区,/就像一棵树商陆/孤独寂寞,没有一朵花,/我也是;/痛苦的受害者/在我生活的年代,/就像一棵树商陆/长在这个地区”。Silva Valdés 和 Filiberto 作曲,Gardel翻译。

㉕(1887—1975)乌拉圭诗人,作曲家和剧作家。

㉖有人说,在其根部埋藏着宝藏,是在对拉普拉塔河区域的沉船救援时发现的。

㉗图1来自军事地理服务;图2、4~5由作者自摄;图3、6~8来自OMBÚes展览目录集,费加里博物馆,2016年;图9来自乌拉圭摄影中心。

(编辑/刘玉霞)

1 Introduction

Ombu is the common name of the plant species Phytolacca dioica in Uruguay.It is a purpose and a means of the university project“OMBÚes.Values associated with nature” that articulates research,teaching and extension.The name of the project includes a set of letters and words that enable several meanings (valid in the Spanish language).For this the poetic license of combining uppercase and lowercase in the same word is used.Thus,it is possible to simultaneously read the singular and the plural to highlight dualities at a quantitative level (the interest for isolated individuals and groups of ombu trees) and at a qualitative level (the study of values associated with the species in general and with particular individuals in particular).A set of relationships is also enabled that emphasizes meanings by including the present of the verb “ser”①and with this the suggestion of essential attributes:“the ombu is”,“the nature is”,“the man is”...

This project aims to raise awareness about the value of landscapes and local histories in interaction with natural components.It focuses on practices and representations associated with the ombu trees.Thus,this strengthens territorial and cultural integration in Uruguay.

When the ombu trees are taken as a purpose of this work,interdisciplinary research is carried out based on its emblematic nature from a landscape point of view.Art is linked to human,social and natural sciences covering different disciplines[Architecture,Computer Engineering,Surveying,Sociology,Anthropology,Ethnobotany,History,Fine Arts (plastic arts,drawing,literature,music,theater),Cartography,Geography,Didactics and pedagogy,Research methodology,Human ecology].

When the ombu trees are taken as a work instrument,teaching and extension activities are carried out.In these the ombu tree in particular(associated with practices) and knowledge and forms of expression in general (representations),officiate as an instrument of inspiration and integration.Values associated with education,social integration and the feeling of belonging to a community are put into play.

Phytolacca dioica is an indigenous species of the humid Pampas.His choice as a thread of these works articulates this characteristic with its symbolic and plastic qualities (its dimensions,its powerful silhouette,its tortuous structure,its medicinal properties,its longevity,its cool shade,its resistance to strong winds).This justifies that the ombu tree is an emblematic species of the Pampa and of capital importance in the identity and cultural heritage of Uruguay.

2 Geographic context

La Pampa is a geographical area of South America where a large steppe predominates frequently whipped by strong southwesterly winds called “pamperos”.The humid pampa is a subregion(600.00 km2) that covers Uruguay,northeastern Argentina and southern Brazil.It consists essentially②of meadows that grow in extensive plains,except for the undulating Pampas around the Río de la Plata and the Paraná River.Phytolacca dioica is an emblematic species of this region,which extended its dispersion area with the presence of man.The livestock introduced by the Spaniards in the 17th century favored the growth of soft grasses that replaced the high native hard pastures.

The República Oriental del Uruguay,geographic focus of development of this study,is a country of about 187.00 km2,located between 30° and 35° south latitude and 53° and 58° west longitude (Fig.1) .

The original vegetation of the country was of steppe nature,with a predominance of the meadow over the forests.At the moment the territory alternates zones of extensive livestock farming with areas of agricultural and forestry production of pines and eucayptus (exotic vegetation).Native forests occupy less than 5% of the country’s surface.

The population of Uruguay is approximately 3,300,000 inhabitants,concentrating the capital,Montevideo,almost half.

Uruguay possesses the warmth of the encompassing,forming a land of nuances[1],geographical,ecological and anthropic articulation at the regional level.“To be Uruguayan” implies then to be the fruit of a cultural mixture,depository of a sensitivity and a mentality,articulators of foreign heterogeneous roots with local characteristics.

3 Institutional context

The project “OMBÚes.Values associated with nature” was born in the year 2013.It is coordinated by the Facultad de Arquitectura,Diseño y Urbanismo (FADU) of the Universidad de la República (Udelar)③.The Communication Service,the Computer Support Service and the Degree in Visual Communication Design also participate in the FADU.Students and teachers of the Landscape Design Degree (ldp) of the Eastern Regional University Center (CURE Udelar) took part.The Laboratory of Botany of the Faculty of Agronomy(fagro Udelar) also collaborates.The Faculty of Engineering (fing Udelar) contributes on its part from the Institute of Computing (INCO) and with students of the career of Computer Engineering④.

The project is inserted in the Plan of Activities of the Design Institut (idD) of the FADU,from where it is coordinated.From there he interacts with different lines of work.In 2014—2015,it obtained financing from FADU in the internal call for extension projects.In 2016 it received support from the Figari Museum of the Ministry of Education and Culture,as a result of which a museum exhibition was organized and a book-catalog was published.In 2017,it obtained financing from FADU in the internal call to Integral Training Spaces.

The support of the Ministry of Education and Culture in 2016 and 2017 has been obtained by inserting the project in the annual call for the Week of Science and Technology (SEMANACYT)⑤.As a result of the activities with schools developed in the SEMANACYT of 2013 and 2014 school workshops were born.These are basic in the extension activities of the OMBÚes project.

4 Theoretical framework

I start considering the landscape as an articulation between practices and human representations associated with nature.In turn,I take nature as a cultural notion.The landscape is therefore a mediator between society and natur[2].The social representations of landscape are based on models inspired by materiality,myths and symbols of nature[3].I also consider that nature,real and represented,is a fundamental factor of social identity and it conditions the construction of the human habitat[4].

Nature is then the fruit of a collective construction.The vegetation in general and the trees in particular are ideal representatives of nature for its evocative capacity.Its complex physiology favors metaphorical or symbolic analogies[5].The formal characteristics of trees influence how they are perceived,in their associated representations and,therefore,in how they are valued and used in landscape architecture.This is how natura naturans (creative nature) and natura naturata (created nature) are related[6].

Also,given that the age of arboreal specimens is generally greater than that of people,the values associated with trees involve collective memory,social imaginaries and the identity of nations.This was demonstrated by Schama in relation to the English greenwood,the Lithuanian-Polish puszta and the Yosemite forest[7].Through these values it is possible to analyze the complex relationships between nature and the human being (in its double condition of belonging to and external to it).

This work is framed in the Paradigm of complexity.This is based on three basic principles:the dialogic (the overcoming of antagonisms in a higher construction),the recurrence (circular and loop effects that affect every human phenomenon)and the hologrammatic (which shows that the whole is in the part,just as it is in the whole)[8].These principles allow to link the theoretical aspects with the methodological aspects of the OMBÚes project.They also support the extrapolation of Phytolacca dioica qualities to landscape values.These values are expressed in practices,knowledge and representations associated with the humid Pampas.They include literary,pictorial,photographic and musical works.They also cover social,landscape,urban and architectural practices.They also favor the birth of myths,legends and anecdotes associated with the species,isolated specimens and groups of ombu trees.

5 Approach and methodology

The conceptual premises are applied to the methodology and a collaborative work strategy is followed.In-person activities are linked (workshops in schools,university teaching activities,exchanges with local actors,museum exposition) and ICT(content portal www.ombues.edu.uy).University research,education and extension is articulated.These are purpose and means to each other,which potentiates the creation of knowledge,according to Morin.For Morin,knowing involves a process in a loop between separating to analyze and relating to synthesize or to make complex[9].

An important process in the organization of the obtained information consists in the assembly of a cartographic representation.This is built collaboratively and shared on the content portal www.ombues.edu.uy[10].Representative samples of ombues and associated practices are mapped.Cartography is taken as part of the social processes of territorialization.It is the product of technical and symbolic operations by means of which human societies give meaning and identity to their vital spaces,mark them,appropriating them[11].Collaborative work creates a feeling of community,an environmental awareness and a collective responsibility towards our landscape heritage.

6 Phytolacca dioica and the pampa landscape

Cada comarca en la tierra

Tiene un rasgo prominente:

El Brasil,su sol ardiente;

Minas de plata,el Perú,

Montevideo,su cerro;

6 《拉潘帕》(佩德罗·费加里摄,1923年)En La pampa,by Pedro Figari (1923)

Buenos Aires —patria hermosa_

Tiene su pampa grandiosa;

la pampa tiene el ombú.⑥

—Luis Lorenzo Domínguez “El ombú”(1837)

The genus Phytolacca (from the Greek,phyton,vegetal and lacca,laca) comprises 35 species.The specific epithet dioica advances one of the basic characteristics of the ombu trees.This term means that the flowers are unisexed and they are located -the masculine and the feminine- in different individuals.Although the flowers and fruits are not particularly prominent,the dioic character of the species contributes to some confusion in its identification at the popular level.Even Pérez Castellano⑦,in the 19th century,came to think at first that they were two different species[12].Then,only the female foot produces fruits and as a result only groups of ombu can form spontaneously around female individuals.In the Pampa,in general,the ombu is isolated,highlighting its silhouette in the immensity of the landscape.In Uruguay it is also found forming groves as in the departments of Lavalleja and Rocha (Fig.2) also,occasionally,integrating the riparian forest.

The ombu develops tree-like bearing and a round treetop,whose diameter and height oscillate between 10 and 14 meters[13].It stands out for its thick trunk that can reach seven meters in diameter.It is divided into several arms.These then derive in an intricate and powerful branching system.It has superficially prominent roots.When individuals grow isolated the roots are confused with the base of the trunk,particularly enlarged.

It is difficult to make a botanical taxonomy of the Phytolacca dioica.In general to classify plants in trees,shrubs,bushes and herbs,several qualities are taken into account:the duration of the plant cycle,the specific dimensions,the consistency(woody or herbaceous) of the tissues and the habit of growth.The ombu combines qualities and characteristics of different categories.It has,on the one hand,its own dimensions of the trees and,on the other hand,a system of distinctive branches of the bushes.Likewise,it is a perennial and very long-lived plant,which is limited to woody plants,trees and shrubs.However,in contrast to these qualities,its consistency is herbaceous.For these peculiarities some consider it a tree,others a bush and others a giant grass.Here,following Professor Atilio Lombardo,we prioritize the corpulence of the ombu and its longevity,taking it as a tree[14].

In the chemical composition of its organs are substances (quercetin,ombuine,essential oils,peroxides,phytolaccin,sapogenins,sucrose[15]that enable utilitarian uses,medicinal applications as well as induce toxic properties .

The lack of precise knowledge in this regard provokes feelings of fear and respect.The resulting mystery inspires myths and anecdotes.There are stories that refer to the general toxicity of the ombu tree,although in fact it only concentrates on the bark and the root.In other times,they have appreciated it because it allowed the manufacture of soap[12].And at the popular level reference is made to its purgative qualities that were used to make tea and to frighten some unwelcome visitor (they say that this was used,in other times,for the unwanted suitors of the young marriageable women).

Phytolacca dioica has many common names,depending on the languages and regions.Many times these confirm or complement the characteristics that are advanced in the scientific name.In Spanish it is called “ombú” (in Uruguay and Argentina),“rey de la pampa” (in Argentina) and “bella sombra” (in Spain and Australia).In the Amerindian language Charrúa,in Uruguay and Argentina,the denomination “lajau”corresponds to him.In Guarani it is called “ümboü”(Uruguay,Argentina);in tupi,“caruru-guassú”(Brazil) and “umbu” (in tupi-guaraní,Ecuador,Paraguay,Mexico,Chile and Australia).In French it is called “Bélombra”;“Raisinier dioïque” (France).

In Brazil it receives different denominations,some of which cause it to be confused with other species.For example,“umbú”,“imbú”,“ombú”,“umbuzeiro” is also the name given to the Spondia tuberosa,a species native to the sertão,in northeastern Brazil.

I already clarified that Phytolacca dioica is an indigenous species of the humid pampas⑧[15].This was decisive in his choice as the core of this study,since it has basically preceded the civilizatory process of the territory.Then it has evolved together with him.It has accompanied our productive,social and cultural processes,at rural and urban levels.The ombu wooed the warlike conflicts of the nation’s origins.He escorted the great estate ranches and small ranches;to the nomadic life of the gaucho⑨and to the sedentary life proper to the development of cities.This explains the association between the ombu trees and the taperas⑩,as well as between the ombú and the pulperías⑪.There are still proofs of this today.Some have been immortalized in representations,such as the woodcut “Pulpería y ombú” by Guillermo Rodríguez (Fig.3).Of others there are only historical records.Some are still standing,like the pulpería of “Lata Vieja” in Cardona,where there is still an ombu next to the recycled building of the pulpería (Fig.4).

Many hulks of cattle ranches were named alluding to the ombu (because they owned one next to the main building).When these were derived in urban centers it influenced the place names.This is the case of the city of Ombúes de Lavalle or the town of Ombúes de Oribe (Fig.5).

The herbaceous consistency of the ombu means that firewood can not be obtained from it to feed the fire (very used as a source of heat or for cooking food in the River Plate culture).This has prevented the ombu tree from being pruned for this purpose.In compensation,the wide tree canopy offers a cool shade.This becomes the center of the story “Shadows” of Juceca⑫.With that absurd sense of humour of the rural world that characterized him,Juceca tells us about a character who sells to another the shadow of an ombu,without the ombu tree.

The ombu offers refuge,both from the sun and from the strong Pampean winds.On the other hand,the ombu benefits from the organic waste that accompanies domestic life.The longevity of the ombu leads to many individuals having a life cycle greater than that of the humans that accompany them.Even the buildings that have been erected close to their protection have a shorter life.

All these qualities have inspired imaginaries that feed popular legends as well as various artistic representations.Although the Phytolacca dioica nowadays is cultivated like ornamental tree in diverse temperate and subtropical regions of the world,these myths and representations are own of the places of where this is native.There is a belief that the house that is protected by the ombu will end in ruins;the fear that a nap under his glass leads to madness or superstition that at night the glass illuminates with a mistery of white light.These ideas were left by W.H.Hudson⑬at the beginning of the 20th century in his work El ombú y otros cuentos rioplatenses[16].

As a counterpoint,in the fantastic story of Horacio Quiroga⑭,El lobizón,(1906) the darkness and silence of the night mix with the fear caused by growls that come from the countryside.And the ombu is the chosen place for the fight between the dogs of the house and the unknown intruder.

It is related to the ombu with its emblematic landscape,the pampa.This is reflected in the fragment of the L.L.Domínguez⑮poem that heads this section.This is associated with various historical circumstances.

7 在乌拉圭Treinta y Tres的克夫拉达德·洛斯库埃沃斯附近的树商陆Ombu tree in an area near the Quebrada de los Cuervos,Treinta y Tres,Uruguay

8 乌拉圭,马尔多纳多,拉科罗尼亚的树商陆Ombu tree in la Coronilla,Maldonado,Uruguay

9 西班牙林荫大道酒店的树商陆,蒙得维的亚,乌拉圭(约1915年)Ombú de Bulevar España,Montevideo,Uruguay (ca.1995)

In the 17th century,Hernando Arias de Saavedra,authorized by the King of Spain,introduced cattle and horses into the territory east of the Uruguay River.This,when developed,changes the environmental and economic balance of the country.

In the 18th century,the Uruguayan and Argentine nations began to be forged.Uruguay managed to establish itself as a state in 1825,becoming independent of Spain,Portugal,Brazil and the United Kingdom.Towards 1728 lands are granted to explode like “suertes de estancias”.The wars continued to affect the country during practically the entire 19th century.In the first half of the nineteenth century the Uruguayan society gave much importance to the game and the feelings were clearly expressed.The dominant mentality could be called the “barbaric culture”[17],where the gaucho reigned..There is even a literature associated with it.The Martín Fierro (1872) by José Hernández⑯is a paradigmatic representative of the gaucho genre,where the ombu is not missing:“… Después de mucho sufrir/tan peligrosa inquietú/,alcanzamos con salú/a divisar una sierra/y al fin pisamos la tierra/en donde crece el ombú…”⑰At the end of the 19th century,the field was fenced in,which would forever change the rural social aspect:the gauchos were replaced by salaried laborers.Between 1860 and 1920 the historian Barrán situates a new sensibility,the “civilized culture”.In this new sensibility,the impulses are repressed and the work,modesty and dignity of death are sacralized[18].It can be considered that Uruguay begins its social,political and economic modernization.Urban life flourishes and the city of Montevideo begins to clearly differentiate itself from the surrounding nature.

Of the more than 130 authors (painters,writers,musicians,photographers,botanists) that are being studied in our project almost half was born in the nineteenth century and the other in the twentieth century.They are distributed equally between Uruguayans and Argentines⑱,with a very small percentage of nationalities of European descent.Their references to the ombu trees follow different profiles..Some scientists,others utilitarian and others more artistic.Within the latter the profiles go from the descriptive to the symbolic,exalting qualities associated with space and others associated with the gaucho,the idea of nation and values of the articulation of the landscape of the Pampa with historical time:immensity,loneliness,violence,freedom,strength,character and pastoral idyll.

Jules Supervielle⑲turns the ombu into the protagonist of a poem (Dans la pampa,1919) and mentions it in his work Boire à la source (1950),where he gives special importance.

The ombu was a leitmotiv in the work of Pedro Figari⑳.It is the protagonist in his painting En la pampa (Fig.6) and an obligatory reference in his paintings and stories.He names it as “our baobab”㉑given the similarity between the powerful structures of both trees.

In his story “Muchachos”,Morosoli㉒refers to a character who left his life in the town to go live in the capital city.The first involved tranquility,enjoyment,the clear water of a stream within reach and an ombu tree,just for him,which was as big as a house.The migration to the capital had made him lose that pastoral idyll:“Just now he realized that the other was right.I had always worked.Always.He had not noticed anything.Lived without living.”

Today,José Risso㉓has dedicated a part of his work to the photography of ombu trees in rural areas.He has done it with analogical photographs,in black and white,praising the personality of the tree and the mystery that surrounds the specimen and the landscape in which it is inserted (Fig.7,8).

The references to the ombu tree also reach the musical genre.Clave del aire is a tango interpreted by Gardel in Paris,in 1930,whose lyrics㉔were written by Fernán Silva Valdés㉕.It is about a loving betrayal,about loneliness and pain.Appeals to qualities(loneliness,roots in the region,refuge,strength)common to the species and to the anecdote that seals the sad essence of this typical dance of the Río de la Plata.

The ombu is also one of the native trees more known by the people of the city[19].This is due not only to the popular imaginary related to the species but also to the presence of outstanding specimens.In Montevideo,for example,the Ombú de Bulevar España (Fig.9) is one of the best-known trees in the city[20].This specimen,which still exists,was already an adult in 1912,when the avenue was projected.Thanks to the intervention of the Mayor of Montevideo of the time,Ramón Benzano,the road layout was redesigned to conserve the tree.

There are also ombu trees along the banks of the Miguelete stream and on the coastal strip of the Río de la Plata.The latter officiated as lighthouses for the boats that came to our coast.Some in particular,like the Ombú de La Mulata,has an associated urban legend㉖and has marked the toponymy of the neighborhood.

In contrast to the great variety of representations,legends and anecdotes,in Uruguay,only recently the ombu tree cultivation has spread.

Encontraste con la gran variedad de representaciones,mitos y leyendas,en el Uruguay,sólo recientemente se ha difundido el cultivo del ombú.Most of the existing specimens derive from their spontaneous reproduction.However,by superstition in general they are not extracted.

7 Conclusion and perspectives

“As much as we separate nature and perception in two different domains,they are in fact indivisibles.Even before being the rest of the senses,the landscape is the work of the spirit.Its essence is built from stratums,both of memory and rocks.[9]”

The intention of this project is to attend to the complexity to which Simon Schama alludes in this heading.The interdisciplinary nature of the research allows to articulate practices and representations,theoretical knowledge and real spaces.The collaborative nature of all this work allows us to collectively build and value our heritage,tear down disciplinary and territorial borders,in short,strengthen our identity.The continuous round-trip between the popularization of scientific culture and the wisdom of popular culture allows knowledge to be constructed transdisciplinarily.

This is an open project in which there is still much to be done.In it,knowledge is used as an instrument of integration,as part of a collective consciousness and as a space for diversity.

Notes:

① in Spanish the verb “to be” is enriched by breaking down into two verbs “ser” and “estar”.

② “Pampa” derives from a Quechua word that means "flat surface”.

③ In Uruguay,the Universidad de la República is the most important institution of higher education and research.It also carries out activities with the purpose of spreading the culture and giving a socially valuable use to knowledge.“It is a public institution,autonomous and co-governed by its teachers,students and graduates”;cited from http://www.universidad.edu.uy.

④PARTICIPANTS:idD FADU Udelar[please aupdate]:Ph.D.Ana Vallarino (in charge;Lead Researcher);Dip.Arch.Laura Pirrocco ;Bach.Leandro Reimundi;Arch.Claudia Costa;Bach.Santiago Ventós/Mag.Arq.Leticia de la Vega (Ext.colab.2014—2015);Natalia Campos (assistant year 2015);Fabiana Oteiza (assistant year 2014)/Ing.Agr.Pablo Ross(botanical advice ldp CURE)/Gabriela Speroni botanical advice fagro)/Cynthia Olguin (visual communication design fadu Udelar,2014—2015);Nicolás Torres (computer developer fadu Udelar,2014—2015/INCO fing:Ing.Raquel Sosa (in charge of engineering students);engineering students:Virginia Yemini and Martina Señoris (app designers);Leonardo Vidal(2014)/LDCV:Prof.Sebastián Suárez and Darío Invernizzi/plastic artist Fernando Stevenazzi (2016—2017).

⑤“Every year during the month of May we celebrate the science and technology developed in Uruguay through various activities suitable for all types of public in order to inspire the enjoyment of knowledge and the vocation of future generations”;cited from http://www.semanacyt.org.uy/.

⑥Each region on earth/It has a prominent feature:/Brazil,its burning sun;/Silver Mines,Peru,/Montevideo,its hill;/Buenos Aires -patria hermosa_/It has its great pampas;/the pampa has the ombú.

⑦ (Montevideo,1743—1815) priest,politician,farmer and great self-taught scholar,of great importance in his time.

⑧ In a strict sense it is not like this:Lombardo clarifies that it did not originate in Uruguay,but that our country covers only its area of dispersion (Lombardo,1969).

⑨ Characteristic inhabitant of the Pampa,skillful rider,of transhumant life,with his life tied to the cattle works,to the consumption of the meat and to the use of the leather.

⑩ dilapidated and abandoned ranch.

⑪Store where items of daily use were sold,mainly edible.

⑫Julio César Castro (1928—2003):Uruguayan writer,actor and playwright.

⑬(1841—1922) Naturalist and English writer of Argentine origin.He lived for a time in Uruguay (then Banda Oriental)and masterfully embodied in his work the rural and warlike atmosphere of the time as well as the idiosyncrasy of the gaucho.

⑭(1878—1937) Uruguayan storyteller,playwright and poet.

⑮Luis Lorenzo Domínguez (1819—1898),Argentine poet,journalist and politician.

⑯(1834—1886) military,journalist,poet and Argentine politician

⑰“After a lot of suffering a very dangerous concern,we reach with health to see a hill and finally step on the land where the ombú grows”.

⑱The study of Brazilian authors has not yet been studied in depth.

⑲(1884—1960) Franco-Uruguayan poet and writer.

⑳(1861—1938) prominent Uruguayan painter,lawyer,politician and writer.

㉑The Baobad was immortalized by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry in Le Petit Prince (1943).

㉒Juan José Morosoli,Uruguayan writer (1899—1957).

㉓Photographer born in Maldonado,Uruguay,in 1970.

㉔“Como el clavel del aire,/así era ella,/igual que la flor/prendida en mi corazón./…/En esta región,/igual que un ombú/solito y sin flor,/así era yo;/y presa del dolor/los años viví,/igual que un ombú/en esta región…”.Like the air plan,/so was she,/like the flower/on my heart.//[In this region,/like an ombú/alone and without a flower,/so was I;/and prey of pain/the years I lived,/like an ombú/in this region” SILVA VALDÉS F and FILIBERTO J D (composers);GARDEL C(interpreter).Clavel del aire.Montevideo,1929.

㉕(1887—1975) Uruguayan poet,composer and playwright.

㉖It was said that under its roots there was a buried treasure,the result of the rescue of the wrecks that were in that area of the Río de la Plata.

㉗Fig.1©Servicio Geográfico Militar;Fig .2,4,5©autor;Fig.3,6~8©OMBÚes exhibition catalog,Figari Museum 2016;Fig .9©Centro de Fotografía,Uruguay.