Surgical management of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: Classical considerations and current controversies

2019-09-05QianQianShaoBangBoZhaoLiangBoDongHongTaoCaoWeiBinWang

Qian-Qian Shao, Bang-Bo Zhao, Liang-Bo Dong, Hong-Tao Cao, Wei-Bin Wang

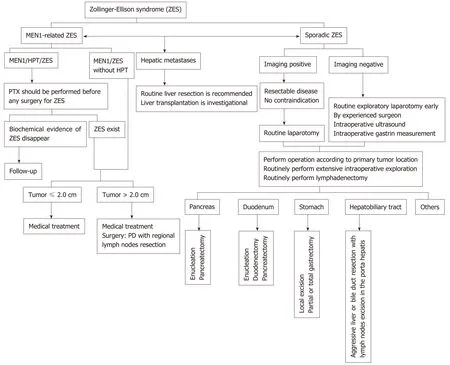

Abstract Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES) is characterized by gastric acid hypersecretion causing severe recurrent acid-related peptic disease. Excessive secretion of gastrin can now be effectively controlled with powerful proton pump inhibitors,but surgical management to control gastrinoma itself remains controversial.Based on a thorough literature review, we design a surgical algorithm for ZES and list some significant consensus findings and recommendations: (1) For sporadic ZES, surgery should be routinely undertaken as early as possible not only for patients with a precisely localized diagnosis but also for those with negative imaging findings. The surgical approach for sporadic ZES depends on the lesion location (including the duodenum, pancreas, lymph nodes,hepatobiliary tract, stomach, and some extremely rare sites such as the ovaries,heart, omentum, and jejunum). Intraoperative liver exploration and lymphadenectomy should be routinely performed; (2) For multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1-related ZES (MEN1/ZES), surgery should not be performed routinely except for lesions > 2 cm. An attempt to perform radical resection(pancreaticoduodenectomy followed by lymphadenectomy) can be made. The ameliorating effect of parathyroid surgery should be considered, and parathyroidectomy should be performed first before any abdominal surgery for ZES; and (3) For hepatic metastatic disease, hepatic resection should be routinely performed. Currently, liver transplantation is still considered an investigational therapeutic approach for ZES. Well-designed prospective studies are desperately needed to further verify and modify the current considerations.

Key words: Zollinger-Ellison syndrome; Sporadic gastrinomas; Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1; Hepatic metastatic disease; Surgical treatment

INTRODUCTION

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES) is characterized by severe recurrent peptic disease and hypersecretion of gastric acid resulting from gastrinomas[1]. Approximately 75%of gastrinomas are sporadic, and 25% of patients have multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1)[2]. There are two therapeutic goals in patients with ZES: To control the hypersecretion of gastric acid and to treat the gastrinoma itself. Excessive secretion of gastrin can now be effectively controlled by the administration of powerful proton pump inhibitors, which have significantly decreased the morbidity and mortality resulting from severe ulcer disease[3]. Therefore, the development of gastrinoma is the main determining factor of the long-term prognosis, and the role of surgery for ZES has instead shifted to eradication of the primary tumor and control/prevention of distant metastases[2,4].

The surgical strategy differs in patients with sporadic ZES and MEN1-related ZES(MEN1/ZES), and the role of surgery in patients with ZES is controversial, especially in those with MEN1. Over half of the gastrinomas are poorly differentiated and have a malignant potential, which dramatically decreases survival and worsens the prognosis[5-7]. Therefore, early surgical exploration and excision of primary lesions should be routinely performed to prevent distant spread in patients with ZES.Unfortunately, only half of patients with sporadic ZES and almost no patients with MEN1/ZES could achieve complete surgical resection[8].

Surgical treatment is the only way to cure the disease, and removing all the lesions(primary and metastatic) is still indicated in most cases. However, many aspects of the surgical management of ZES (such as timing of intervention, extent of resection, and surgery for advanced disease) are controversial topics. The current article will present the classical considerations and controversies regarding the surgical management of ZES.

SURGICAL TREATMENT OF SPORADIC ZES

Timing of surgery

Recent guidelines and studies recommended that patients with potentially resectable sporadic gastrinoma should routinely be offered exploratory laparotomy with curative intent, if no contraindications for surgery exist[5,9-12]. Moreover, after resection of sporadic ZES, 50%-60% of patients were free of disease immediately and the disease-free survival rate at 10 years is 35%-40%[2,13,14]. Surgical resection in ZES patients protects against the possibility of hepatic metastases and increases survival[4,15-17].

Approximately 30% of tumors in patients with sporadic ZES cannot be precisely located by preoperative explorations, including more than 60% of tumors ≤ 1 cm in size[18]. When the location of the gastrinoma is not confirmed by preoperative investigations, the decision to perform surgical exploration is controversial. A careful review of the case should be made before the decision about whether to perform surgery. If surgery is indicated, thorough abdominal exploration through laparotomy,intraoperative ultrasound, duodenotomy with transillumination, and routine lymphadenectomy should be included[19-21]. A prospective study conducted by Norton et al[22]indicated that in the hands of an experienced surgeon, lesions could be found in 98% of imaging-negative ZES patients, and nearly 50% of them were cured. This rate was similar to that in imaging-positive patients. In this study, for patients in whom the location of the gastrinoma was not confirmed preoperatively, mean delay from the onset of ZES to surgery is 8.9 years[22]. Seven percent of patients with negative imaging findings had liver metastases at the time of surgery, and all diseaserelated deaths occurred in this group, which may have been caused by the long delay before surgery. Therefore, Norton et al[22]recommended that surgery should be routinely performed as early as possible in sporadic ZES patients despite negative imaging findings. In another prospective study, Bartlett et al[23]found that for patients with radiographic evidence of metastatic disease and occult primary tumors, the primary lesion could be identified in 89% of these patients. This study indicated that surgical management should not be influenced by an inability to localize the primary tumor[23].

Localization of sporadic ZES

Localization is significant for a cure but can be challenging.

Duodenal or pancreatic origin:More than 80% of primary gastrinomas are classically located in the pancreas and duodenum within the gastrinoma triangle, which is an important anatomic mark for localization[16,24-27]. Gastrinomas in the pancreas have a higher malignant potential than those in the duodenum[27]. Moreover, for MEN1/ZES patients, 60%-90% of lesions are located in the duodenum. These tumors are usually small, can hardly be seen on endoscopic ultrasound or preoperative imaging investigations, and can be found only at exploratory laparotomy[2,18,28-30]. In selected cases, empirical diagnostic surgery with duodenotomy may be considered[13].

Lymph node origin:Although there have been several reported cases of primary gastrinomas of the lymph nodes, the existence of sporadic ZES of lymph node origin is controversial[19,31-33]. These cases have been explained by occult primary microgastrinomas of the pancreas or duodenum resulting in metastases to the liver or lymph nodes[19]. A recent study reported that 28.2% of ZES patients had gastrinomas of the lymph nodes and were less likely to have recurrent or persistent disease than patients with gastrinomas of other origins (9.1% vs 42.9%, P = 0.04)[34].

Hepatobiliary tract origin:A recent prospective study reported the existence of very unusual ZES originating from the hepatobiliary tract[35]. Norton et al[35]found that of 233 sporadic ZES patients who received surgery to excise the lesions, 3.1% had primary gastrinoma origin from the liver or biliary tract, which ranked as the second most frequent extraduodenopancreatic primary location. Because the rates of survival and long-term cure are high, and the rates of complications are acceptable, aggressive liver or bile duct resection is indicated. In addition, their findings indicated that given that nearly 50% of patients will develop lymph node metastases, lymph nodes in the hepatic portal should be routinely removed.

Gastric origin:The incidence of gastrinomas of gastric origin has increased in the past 50 years[36]. In recent years, an increasing incidence of subclinical gastric gastrinomas has been found by panendoscopic examination. Gastric gastrinomas can be treated by local excision, such as endoscopic submucosal dissection or endoscopic polypectomy,but partial or total gastrectomy may be needed if recurrence occurs[37,38]. Additionally,because of lower grades and less frequent lymph node and hepatic metastases,gastrinomas originating from the stomach were found to have better long-term outcomes than gastrinomas of other origins[39].

Other origins:Other very uncommon primary sites include the ovaries, heart,omentum, and jejunum[2,40].

Type and extent of surgery

The vast majority of cases of sporadic ZES are associated with single tumors, and the surgical approach depends on the location of the gastrinomas. Sporadic gastrinomas located distant from the pancreatic duct may be amenable to enucleation. Resections are required for tumors that are close to the pancreatic duct (less than 3 mm). Distal pancreatic resection should be performed for pancreatic head tumors, and duodenotomy should be routinely performed to detect small duodenal lesions[41,42].Distal pancreatectomy (with or without splenectomy) is indicated for sporadic gastrinomas located in the body or tail of the pancreas. Pancreaticoduodenectomy(PD) should be preferred for most patients with gastrinomas located in the head,uncinated process, or neck of the pancreas. PD is also indicated for patients with local recurrence or persistent tumors after the first surgery[21].

The presence of hepatic metastases is an important prognostic indicator in ZES patients; primary hepatic tumors have been reported, and liver metastasis from duodenal or pancreatic gastrinomas is frequent. Thus, it is well established that intraoperative liver exploration should be performed routinely[43]. However, routine lymphadenectomy remains controversial, not only because of the controversy regarding whether primary lymph node gastrinomas exist[19,32-34,44]but also because the importance of identifying lymph node metastases, with some studies indicating that they have prognostic meanings but others finding the opposite[15-16,43,45]. An increasing number of studies have investigated the significance of lymph node metastases in the ZES; lymph node metastases are reported to occur in 42%-82% of ZES patients[43-47];furthermore, the postoperative survival rate is reported to be significantly reduced,and the time to develop liver metastases is reported to be significantly shorter in patients with positive lymph nodes than in those with negative lymph nodes[43-45].Krampitz et al[43]reported that the disease-related decrease in survival was associated with the number of involved lymph nodes. Each of these studies indicated that lymphadenectomy should be routinely performed in ZES patients and that this treatment not only can prevent recurrence and increase survival but also has significant prognostic value[43-47].

Although a small part of ZES patients who undergo laparoscopic operation have favorable outcomes[48-50], laparoscopic surgery has not been recommended as the standard treatment in patients with gastrinomas for the following reasons: (1) The primary tumor is not seen frequently on preoperative imaging examinations, and complete exploration of the abdomen is needed; (2) The tumors are submucosal in the duodenum and need routine duodenotomy combined with a Kocher maneuver; and(3) Lymphadenectomy should be routinely performed because lymph node metastases frequently occur[34,48].

SURGICAL TREATMENT OF MEN1/ZES

Timing of surgery

The timing and place of routine surgical exploration in patients with MEN1/ZES remain controversial[2,9,51,52]. These patients usually have an unpredictable course and frequently have lymph node metastases, multiple duodenal gastrinomas, and other pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (pNETs)[5,29,53,54]. Consequently, local resection or enucleation rarely leads to a long-term cure. In patients diagnosed with MEN1/ZES,operation other than PD is related to recurrence in almost 100% of patients[2,52]. It is generally recommended that surgery to prevent metastatic dissemination should be restricted to patients with tumors > 2 cm, given that MEN1 patients with pancreatic tumors ≤ 2 cm have fine long-term life expectancy[5,53,55,56]. Recent European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society/North American Tumor Society (ENETS/NANETS)guidelines recommended that routine surgery for a possible cure should be reserved for ZES patients with lesions > 2 cm but should not be performed routinely[11-12].Furthermore, as surgery is the only way to prevent or cure malignant transformation[52], others have indicated that early surgical intervention as soon as the diagnosis is made is indicated for all patients with MEN1/ZES[51,55,57,58].

Type and extent of surgery

The excision of pancreatic head tumors, limited surgical resection with excision of duodenal lesions, and distal pancreatectomy have been proposed as surgical alternatives for the treatment of MEN1/ZES[58]. In some cases, total pancreatectomy is considered the therapeutic choice in an attempt to completely remove all tumor lesions. However, such surgical approaches may be frequently associated with a high recurrence rate and low cure rate. A more radical surgical intervention with PD followed by regional lymphadenectomy is proposed for patients with MEN1/ZES[51,58].Since a cure can only be achieved by performing PD, others still recommend routine PD in an attempt to achieve a cure[5,29,53-55,59,60]. Although several studies have reported potential long-term biochemical remission after PD in MEN1/ZES patients, the longterm consequences of PD remain largely undefined, and the real benefit on long-term survival remains controversial[9,21,51,61]. Each approach has its advocates, but there are no prospective data to provide evidence and guidance. Recent ENETs/NANETs guidelines recommended that PD should not be performed routinely[11,12]. However,guidelines from the Polish Network of Neuroendocrine Tumors indicated that an attempt to perform a radical resection can be made if the disease seems to be limited[62,63]. Additionally, intraoperative gastrin monitoring may be helpful to improve the capacity for determining the extent of resection[57].

Ameliorating the effects of other MEN1-related diseases

In patients with primary hyperparathyroidism (HPT) and MEN1/ZES, the effect of parathyroidectomy (PTX) on the behavior of the gastrinoma can be evaluated by fasting gastrin levels, basal acid output (BAO), and secretin provocative testing[64].Some previous studies involving small numbers of MEN1/HPT/ZES patients reported that fasting gastrin levels, BAO, and/or secretin-stimulated gastrin response scan were markedly decreased by PTX[65-74]. In a prospective study including 84 MEN1/HPT/ZES patients, Norton et al[75]convincingly demonstrated that successful PTX had a marked ameliorating effect on these parameters. With surgery to remove only the abnormal parathyroid glands but not directed at the pNET, 20% of patients with MEN1/HPT/ZES no longer had biochemical evidence of ZES. Careful observation is necessary after PTX because primary HPT with hypercalcemia can result in secondary hypergastrinemia, obscuring the diagnosis of patients with MEN1/ZES. Additionally, this finding supports the strategy that before any abdominal surgery is performed for ZES, parathyroid surgery should be performed first.

SURGICAL TREATMENT OF HEPATIC METASTATIC DISEASE

Hepatic resection

For patients with hepatic metastases, several retrospective reports and one recent meta-analysis have demonstrated the benefits of hepatic resection in terms of quality of life and overall survival[76-81]. Previous studies have shown that R0 or R1 resection can result in better long-term survival, and the 5-year survival rates are approximately 60%-80%[76-78]. Liver resection has an acceptable morbidity (approximately 30%) and a low mortality rate (less than 5%). On the other hand, when liver metastases are not resected, the survival rate is about 30%[82,83]. However, considering the retrospective nature of the studies, bias in patient selection (such as less advanced disease and better performance status) may have affected the surgical outcomes. Liver resection for metastases has a therapeutic effect as mass reduction, even if >90%-95%of tumors were resected[84]. Even though a reliable prospective study lacks, some papers recommended aggressive liver resection, not liver transplantation.Intraoperative ultrasound is essential to detect small tumors that were not detected preoperatively and to determine the extent of lesions. Liver function must be assessed precisely, and liver dysfunction should be avoided after the surgery[21].

Orthotopic liver transplantation

Orthotopic liver transplantation has been considered an exploratory option for patients who are not amenable to limited hepatic resection. The 5-year disease-free survival rate was similar (approximately 30%) to that of hepatic resection in the two largest series[85,86]. The heterogeneity of the results was highlighted in a recent systematic review that illustrated the need for well-designed prospective studies[87].Considering the risks involved, transplantation was considered to be an investigational method in the treatment of ZES. Prospective clinical trials conducted in a defined population of patients are needed to determine the true benefits of orthotopic liver transplantation[84].

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, surgical treatment is the only way to cure ZES, but the role of surgery in patients with ZES (especially in MEN1/ZES) remains controversial. Until now,only two management guidelines for gastroduodenal neuroendocrine neoplasms(including gastrinoma) mentioned therapeutic recommendations for ZES, but not in detail[62,63]. Many aspects of the surgical treatment for ZES lack expert consensus. We thus propose a surgical treatment algorithm for ZES based on a thorough literature review of the evidence provided by the current papers (see Figure 1). Well-designed prospective studies and more optimized therapeutic algorithms for ZES are still desperately needed in the future.

Figure 1 Surgical treatment algorithm for Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. ZES: Zollinger-Ellison syndrome; MEN1: Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1; MEN1/ZES:Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1-related Zollinger-Ellison syndrome; MEN1/HPT/ZES: Patients with primary hyperparathyroidism and Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1-related Zollinger-Ellison syndrome; PTX: Parathyroidectomy.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- New Era: Endoscopic treatment options in obesity-a paradigm shift

- Chronic hepatitis delta: A state-of-the-art review and new therapies

- Eosinophilic esophagitis: Current concepts in diagnosis and treatment

- Locoregional treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma: Current evidence and future directions

- Review of current diagnostic methods and advances in Helicobacter pylori diagnostics in the era of next generation sequencing

- Exploring the hepatitis C virus genome using single molecule realtime sequencing