LncRNA SChLAP1调节前列腺癌的凋亡作用及其机制研究

2019-08-15李萍陈伟黄航

李萍 陈伟 黄航

[摘要] 目的 研究LncRNA SChLAP1调节前列腺癌细胞凋亡的可能分子机制。 方法 采用慢病毒转染前列腺癌PC-3细胞,并用qPCR检测转染率;利用凋亡检测试剂盒检测转染PC-3细胞的凋亡情况,通过生物信息学确定其下游的可能靶点。 结果 在不同靶点病毒作用下PC-3细胞可以下调SChLAP1的表达,其中3#位点的下调效率最大达40%。PC-3细胞下调后,与阴性对照组相比细胞凋亡比例明显上升,差异有统计学意义。 结论 SChLAP1可以调节前列腺癌细胞的凋亡,而miR-101-5p是其下游的靶点之一。

[关键词] 前列腺癌;LncRNA;SChLAP1;凋亡

[中图分类号] R737.25 [文献标识码] A [文章编号] 1673-9701(2019)16-0026-04

[Abstract] Objective To investigate the possible molecular mechanism of LncRNA SChLAP1 in the regulation of apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. Methods Prostate cancer PC-3 cells were transfected with lentivirus, and the transfection rate was detected by qPCR. The apoptosis of PC-3 cells was detected by apoptosis detection kit, and the possible downstream targets were determined by bioinformatics. Results PC-3 cells could down-regulate the expression of SChLAP1 under the action of different target viruses, and the down-regulation efficiency of 3# locus was up to 40%. After PC-3 cells were down-regulated, the proportion of apoptosis was significantly higher than that of the negative control group, and there was a statistical difference. Conclusion SChLAP1 can regulate the apoptosis of prostate cancer cells, and miR-101-5p is one of its downstream targets.

[Key words] Prostate cancer; LncRNA; SChLAP1; Apoptosis

前列腺癌(prostate cancer,PC)是嚴重威胁全球男性的重要恶性肿瘤。在我国确诊的老年男性人群中,其发病率暂时落后于西方,但却多以肿瘤局部晚期甚至转移为主,导致预后不佳。

LncRNAs是近来分子生物领域研究的热点,已被证实参与多步骤基因的表达和转录过程。尤其在癌症肿瘤的发生和发展中,lncRNAs参与调节重要细胞信号通路。Lnc SChLAP1(second chromosome locus associated with prostate-1)是由Prensner R和Iyer MK在2010年首先发现的,其与前列腺癌的恶性程度、转移以及预后紧密相关,并定位于细胞核[1]。研究中提示Lnc SChLAP1可以发挥促癌作用,其中一种机制是拮抗SWI/SNF复合物的核心蛋白[1],但其在前列腺癌中其他机制仍需进一步研究。

1 材料与方法

1.1 材料和试剂

人前列腺癌PC-3细胞株和人肾上皮293细胞株,均购于上海生命研究院;胎牛血清、F-12K和DMEM培养基均购于Gibco公司(美国);慢病毒颗粒、目的病毒Lenti-EGFP-SChLAP1-mir以及阴性对照病毒Lenti-EGFP均购于上海锐赛科技有限公司(中国);凋亡检测试剂盒(Annexin V-APC-PI Apoptosis Analysis Kit)购于三箭生物技术有限公司(中国);Polybrene聚凝胺购于上海索莱宝科技有限公司(美国);双荧光素酶检测试剂盒购于Promega公司(美国)。

1.2 细胞株的培养、转染和分组

PC-3细胞株均使用F-12K培养基,293细胞株使用DMEM培养基,两者均添入10%的胎牛血清(FBS)、1%链霉素和200 U/mL青霉素。两株细胞置于37℃、5%的CO2培养箱中培养。

1.3 构建 LncRNA SChLAP1 稳定下调前列腺癌细胞

将PC-3的细胞悬液接种于6孔培养板,于培养箱中进行培养。加入相应含量的目的病毒(滴度为4.36×108 TU/mL)和阴性对照病毒(滴度108 TU/mL,MOI=20),并依据病毒不同的滴度,向培养板中加入聚凝胺(8 μg/mL)增强病毒的感染效率。经过感染孵育24 h后,将原含病毒的F-12K培养基替换为无病毒培养基,重置后再培养。再经过孵育48 h后,通过查看GFP的水平,反映细胞的生长情况。qPCR检测转染后细胞的SChLAP1表达。

1.4 SChLAP1下调后PC-3的凋亡水平检测

用EP管收集培养板内转染后PC-3细胞的上清液,将上清液经过1000 r/min的转速离心5 min后,收集EP管底部的沉淀细胞。同时,用胰酶协助收集贴壁的细胞后,同转速离心5 min,再收集细胞。每个组别均用500 μL 1×binding buffer重悬细胞,并慢慢吹打均匀。加入Annexin V(别藻青蛋白标记)5 μL和碘化丙啶5 μL,混合均匀。在避光的条件下,室温20°C孵育30 min,上流式细胞仪检测。

1.5 生物信息学检测

利用TargetSCan human7.0 和starbase V2.0进行生物信息学分析查找目标靶点。此项工作委托上海锐赛生物技术有限公司进行。

1.6 双萤光素酶报告实验

1.6.1 双萤光素酶报告载体质粒的构建 通过萤光素酶报告载体 psiCHECK-2,构建出野生型psiCHECK -SCHLAP1-wt-3UTR。 通过突变SChLAP1 3UTR 中与miR-101-5P互补的序列,从而构建突变型 psiCHECK-SChLAP1-mu-3UTR。

1.6.2 細胞的分组、转染和检测 实验报告采用293细胞系。分组信息如下:(1)空细胞组;(2)SChLAP1野生型组;(3)野生型+NC-mimic组;(4)SChLAP1野生型+miR101-mimic组;(5)SChLAP1突变组;(6)SChLAP1突变+NC-mimic组;(7)SChLAP1突变+miR101-mimic组。每组分别转染3个复孔。

在转染前24 h,使用胰酶消化293细胞后,接入24孔板(8 W个/孔)加入培养基进行培养。转染当天,先将培养基替换为不含抗生素的培养基,再安放于37°C适宜条件下进行孵育,制作转染的混合载体。 甲管:将含双萤光素酶报告载体0.5 μg、不同组mimic 0.5 μL以及 25 μL培养基混匀;乙管: 25 μL转染试剂与3 μL培养基混匀。在20℃条件下,静置5 min,在不同组别甲管中加入乙管溶液。充分摇匀,在20℃条件下进行孵育20 min。再取上述转染混合载体,按各自的组别不同,分别滴入到相对应的培养板孔中,慢慢摇匀置于37°C培养箱中培育。转染6 h后,更换培养基后继续培育。48 h后,查看不同组别转染细胞的转染效率,上酶标仪检测。

1.7 统计学分析

采用SPSS 24.0统计学软件处理数据, 计量资料以均数±标准差(x±s)表示,采用 t检验,多组采用单因素方差分析,P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果

2.1 不同靶点下调PC-3细胞后SChLAP1基因的表达

与NC组相比,在三组不同靶点病毒转染下调后,1#、2#和3#号转染组的PC-3细胞中SChLAP1表达均下降明显,其中以3#组下降尤为明显,下降达40%,并与NC组存在统计学差异(*P<0.05,**P<0.01),见图1。

2.2 SChLAP1下调后PC-3的凋亡比例上升

PC-3细胞下调SChLAP-1后,细胞凋亡的比例明显上升,差异有统计学意义(***P<0.001),见图2。

2.3生物信息学检测

利用TargetSCan human7.0 和starbase V2.0检测,并结合文献分析。在既往的报道中SChLAP1在前列腺癌中表现为高表达,其下游目标基因为低表达。候选目标基因有:miR-100、miR-21、miR-139、miR-25以及miR-21等基因。再通过人工比对的方式,初步选择miR-101-5p 为SChLAP1可能的靶点,见图3,可见两者有8个互补位点。

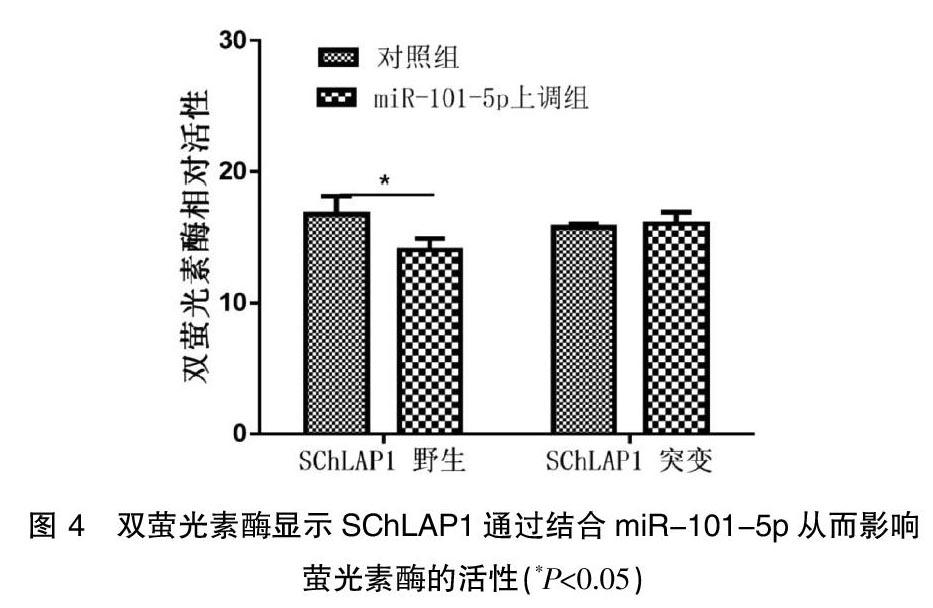

2.4双萤光素酶报告显示SChLAP1可以靶向作用miR-101-5p

通过上调miR-101-5p 后,含有野生型 SChLAP1-wt-3UTR 的萤光素酶活性受到明显的抑制,而同样上调miR-101-5p对含有突变型 SChLAP1-mu-3UTR 的萤光素酶却无法发挥抑制作用,见图4。

3 讨论

前列腺癌在我国的发病率逐年上升,其防治工作越来越重要。二代测序的不断进展后,在前列腺癌领域内起重要作用的lncRNAs不断的被发现和鉴定[2]。其中最具有代表性的是PCA3(Prostate cancer antigen 3),PCA3早在1995年就被发现,后续的研究发现其具有高度的前列腺癌特异性及检验的便捷性,已被发展为前列腺癌重要的诊断方法。而其他LncRNAs如SChLAP1、SPRY4-IT1 和TRPM2-AS等不断被发现、鉴定和验证,丰富了前列腺癌的诊断、治疗和随访领域。但前列腺癌的发生和其他肿瘤的发生相同,其过程是非常复杂的,涉及许多遗传和表观遗传改变,而目前发现的lncRNAs如何发挥其作用仍有较多的研究空白需要填补。

SChLAP1位于2号染色体长臂上,在前列腺癌呈现出高表达[1,3],其高效联系着前列腺癌的预后[1,4,5],高表达SChLAP1更容易发展成致死性前列腺癌[5]。还可以作为独立危险因素用于预测前列腺癌根治术后生化复发,而在转移的前列腺癌中SChLAP1表达量升高尤为明显,从而使SChLAP1有机会成为前列腺癌理想的生物标志物,用于预测前列腺癌的预后[6]。在本研究中也证实下调SChLAP1后,抑制了SChLAP1的促癌作用,PC-3细胞的凋亡明显增加。

尽管逐渐了解LncRNA的功能,但LncRNA的失调正在成为癌症发展和进展的基因调控网络中普遍存在的部分。LncRNAs可以干涉多个过程,包括染色体的调整、细胞增殖控制、细胞分化、细胞凋亡、上皮-间质转化调控以及细胞核和细胞质运输。近期的研究中,LncRNA的调控作用被归纳为三个层次:(1)表观遗传层面[7];(2)转录调控层面[8];(3)转录后调控层面[9]。而目前LncRNA和miRNA的相互作用归纳为三种途径:(1)miRNA调控LncRNA的分解。miR-217调节Ago2通路从而介导降解LncRNA MALAT-1[10];(2)LncRNA可以阻止miRNA与靶mRNA的结合。LncRNA MALAT-1具有与miR-1碱基互补配对的序列,发挥其海绵吸附作用,从而抑制miR-1 的作用[11];(3)LncRNA还可以加工产生miRNAs,从而发挥其作用。研究发现H19可降解生成miR-675,发挥抑制肿瘤转移作用[12]。另外,一些LncRNA与雄激素受体信号传导的再激活和前列腺癌细胞代谢重要相关,可以在各个阶段差异表达从而影响肿瘤的发生和进展。

考慮到LncRNA在前列腺癌中的动态作用,LncRNA也可以作为治疗靶点,有助于防止去势抵抗的发展,维持稳定的疾病并且阻止转移性扩散。在本研究中发现miR-101可作为SChLAP1的靶基因。在既往的研究发现,miR-101在多种肿瘤中与转移相关[13-17]。此外,也有研究确定了miR-101还具有调控细胞周期、促进凋亡[16,18,19]和调节自噬的作用[18,20-22]。而miR-101的上游操纵基因及为何在前列腺癌中会表现出明显的低表达均缺少相关的报道,本研究给出了新的发现和思路。在前列腺癌细胞中SChLAP1发挥其促癌的作用,而这个作用的发挥,很可能通过其互补结合miR-101-5p,从而发挥抑制凋亡的作用。

[参考文献]

[1] Prensner JR,Iyer MK,Sahu A,et al. The long noncoding RNA SChLAP1 promotes aggressive prostate cancer and antagonizes the SWI/SNF complex[J]. Nature Genetics,2013, 45(11):1392-1398.

[2] Taylor BS,Schultz N,Hieronymus H,et al. Integrative genomic profiling of human prostate cancer[J]. Cancer Cell,2010,18(1):11-22.

[3] Lee RS,Roberts CW. Linking the SWI/SNF complex to prostate cancer[J]. Nature Genetics,2013,45(11):1268-1269.

[4] Mehra R,Shi Y,Udager AM,et al. A novel RNA in situ hybridization assay for the long noncoding RNA SChLAP1 predicts poor clinical outcome after radical prostatectomy in clinically localized prostate cancer[J]. Neoplasia,2014, 16(12):1121-1127.

[5] Mehra R,Udager AM,Ahearn TU,et al. Overexpression of the long non-coding RNA SChLAP1 independently predicts lethal prostate cancer[J]. European Urology,2016, 70(4):549-552.

[6] Prensner JR,Zhao S,Erho N,et al. RNA biomarkers associated with metastatic progression in prostate cancer,a multi-institutional high-throughput analysis of SChLAP1[J].The Lancet Oncology,2014,15(13):1469-1480.

[7] Zhao X,Li D,Pu J,et al. CTCF cooperates with noncoding RNA MYCNOS to promote neuroblastoma progression through facilitating MYCN expression[J]. Oncogene,2016,35(27): 3565-3576.

[8] Baldassarre A,Masotti A. Long non-coding RNAs and p53 regulation[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences,2012,13(12):16708-16717.

[9] Tripathi V,Ellis JD,Shen Z,et al. The nuclear-retained noncoding RNA MALAT1 regulates alternative splicing by modulating SR splicing factor phosphorylation[J]. Molecular Cell,2010,39(6):925-938.

[10] Lu L,Luo F,Liu Y,et al. Posttranscriptional silencing of the lncRNA MALAT1 by miR-217 inhibits the epithelial-mesenchymal transition via enhancer of zeste homolog 2 in the malignant transformation of HBE cells induced by cigarette smoke extract[J]. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology,2015,289(2):276-285.

[11] Jin C,Yan B,Lu Q,et al. Reciprocal regulation of Hsa-miR-1 and long noncoding RNA MALAT1 promotes triple-negative breast cancer development[J]. Tumour Biology,the Journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine,2016,37(6):7383-7394.

[12] Zhu M,Chen Q,Liu X,et al. lncRNA H19/miR-675 axis represses prostate cancer metastasis by targeting TGFBI[J].The FEBS Journal,2014,281(16):766-775.

[13] Guo F,Parker Kerrigan BC,Yang D,et al. Post-transcriptional regulatory network of epithelial-to-mesenchymal and mesenchymal-to-epithelial transitions[J]. Journal of Hematology & Oncology,2014,7(19):1-11.

[14] Erdmann K,Kaulke K,Thomae C,et al. Elevated expression of prostate cancer-associated genes is linked to down-regulation of microRNAs[J]. BMC Cancer,2014,14(82):1-14.

[15] Srivastava A,Goldberger H,Dimtchev A,et al. Circulatory miR-628-5p is downregulated in prostate cancer patients[J]. Tumour Biology,the Journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine,2014,35(5):4867-4873.

[16] Liu XY,Liu ZJ,He H,et al. MicroRNA-101-3p suppresses cell proliferation,invasion and enhances chemotherapeutic sensitivity in salivary gland adenoid cystic carcinoma by targeting Pim-1[J]. American Journal of Cancer Research,2015,5(10):3015-3029.

[17] He H,Tian W,Chen H,et al. MicroRNA-101 sensitizes hepatocellular carcinoma cells to doxorubicin-induced apoptosis via targeting Mcl-1[J]. Molecular Medicine Reports,2016,13(2):1923-1929.

[18] Li M,Tian L,Ren H,et al. MicroRNA-101 is a potential prognostic indicator of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma and modulates CDK8[J]. Journal of Translational Medicine,2015,13(271):1-15.

[19] Lei Q,Liu X,Fu H,et al. miR-101 reverses hypomethylation of the PRDM16 promoter to disrupt mitochondrial function in astrocytoma cells[J]. Oncotarget,2016,7(4):5007-5022.

[20] Guo J,Huang X,Wang H,et al. Celastrol induces autophagy by targeting AR/miR-101 in prostate cancer cells[J]. PloS One,2015,10(10):e0140745.

[21] Wu D,Jiang H,Chen S,et al. Inhibition of microRNA-101 attenuates hypoxia/ reoxygenationinduced apoptosis through induction of autophagy in H9c2 cardiomyocytes[J].Molecular Medicine Reports,2015,11(5):3988-3994.

[22] Xu Y,An Y,Wang Y,et al. miR-101 inhibits autophagy and enhances cisplatin-induced apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells[J]. Oncology Reports,2013,29(5):2019-2024.

(收稿日期:2018-12-27)